Abstract

Local protein synthesis in axons and dendrites underpins synaptic plasticity. However, the composition of the protein synthesis machinery in distal neuronal processes and the mechanisms for its activity-driven deployment to local translation sites remain unclear. Here, we employed cryo-electron tomography, volume electron microscopy, and live-cell imaging to identify Ribosome-Associated Vesicles (RAVs) as a dynamic platform for moving ribosomes to distal processes. Stimulation via chemically-induced long-term potentiation causes RAV accumulation in distal sites to drive local translation. We also demonstrate activity-driven changes in RAV generation and dynamics in vivo, identifying tubular ER shaping proteins in RAV biogenesis. Together, our work identifies a mechanism for ribosomal delivery to distal sites in neurons to promote activity-dependent local translation.

Keywords: Neurons, Plasticity, Ribosomes, Ribosome-Associated Vesicles, Local Translation, Electron Microscopy, Cell Trafficking, Endoplasmic Reticulum

Neurons are highly polarized cells that transfer information through complex networks of synaptic connections. There is a consensus that protein synthesis is essential for the formation and remodeling of synapses – key features of synaptic plasticity (1). Neurons rely on local translation in distal processes (i.e., axons and dendrites) to bypass lengthy protein trafficking from the soma (1–4). This enables precise control of protein synthesis in axons and dendrites in response to localized stimuli, facilitating rapid modification of the neuronal proteome that is highly localized in space and time (1). Recent efforts have identified thousands of mRNAs, including Camk2a, Map2, Actb, and Arc, that are distinctly localized and translated in axons and dendrites (1, 5–10). Furthermore, mRNA trafficking is sensitive to neuronal stimulation. Increased activity promotes trafficking and localization of mRNAs at distinct sites in distal neurites. This enables activity-dependent translation, fueling the protein synthesis required for synaptic reorganization (11–17). However, the molecular mechanisms by which neurons target and coordinate the protein synthesis machinery to specific sites in the cell periphery remain poorly understood.

mRNAs that localize to distal axons and dendrites require coordination with local ribosomes to initiate local translation. Yet, while ribosomes have been detected in the neuron periphery (1, 18, 19), translationally active ribosomal assemblies (i.e., polysomes) have been infrequently identified (1, 3, 20). More recent reports have described monosome-mediated translation in neuropil (21), although the mechanisms by which ribosomes are trafficked to distal sites, and their source(s) still remain unclear. Extensive rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) is absent in axons and limited in distal dendrites (22, 23). These observations are at odds with a wealth of in vitro and in vivo biochemical and imaging data that clearly demonstrate local protein synthesis in axons and dendrites and its relevance to plasticity (1, 15, 24–26).

Our recent description of ribosome-associated vesicles (RAVs), highly mobile RER-derived organelles decorated with 80S ribosomes, may offer important new insights into the ribosomal machinery required for local translation within the neuronal periphery (27). We therefore propose that dynamic RAVs provide a mechanism by which active, bound ribosomes are trafficked to distal sites in axons and dendrites to promote local translation.

RAVs are present in neurites

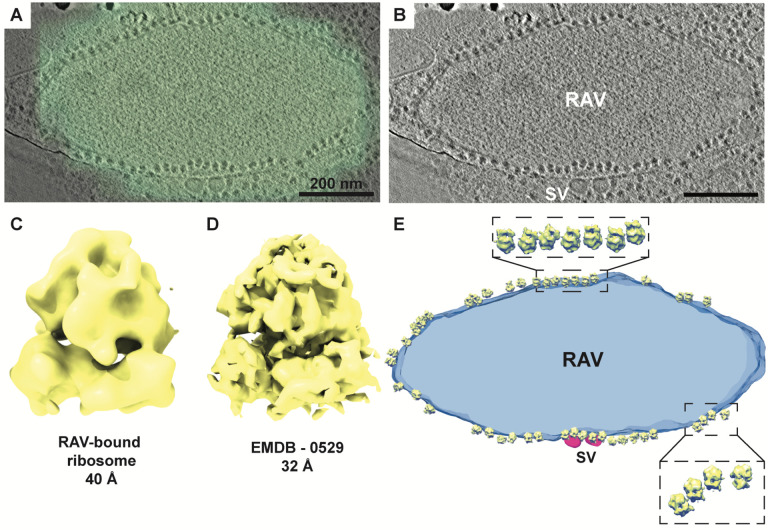

We previously demonstrated that RAVs were present in the dendrites of primary hippocampal neurons by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Likewise, live-cell imaging of the fluorescent ER reporter mNeon-KDEL in primary cortical neurons demonstrated dynamic puncta in peripheral neurites, suggesting that these structures represented RAVs in motion (27). Building on these initial findings, we have comprehensively characterized RAVs and their dynamics in neurons. We first validated that the mNeon-KDEL puncta visualized during live-imaging of our primary neurons were indeed RAVs using cryo-correlative light and electron microscopy (cryo-CLEM) (Fig. 1). In rat hippocampal neurons expressing mNeon-KDEL, cryo-CLEM confirmed that mNeon-KDEL puncta localized to vesicular structures decorated with electron-dense ribosome-like particles consistent with RAVs (Fig. 1A and 1B, Movie S1). To corroborate that the electron-dense particles associated with RAV membranes were ribosomes, we extracted the particles and performed subtomogram averaging. The average of the extracted particles (n=164) reached a ~40 Å resolution (Fig. 1C, Fig. S1). The three-dimensional (3D) structure of the averaged particles strongly resembled a well-defined 80S ribosome structure from Oryctolagus cuniculus previously imaged by cryo-ET (Electron Microscopy Data Bank # EMD-0529) that was down-sampled to 32 Å resolution (28) (Fig. 1C and 1D, Fig. S1), confirming that the RAV-bound particles were indeed ribosomes. Mapping the ribosomes back to their original positions revealed that the ribosomes were organized in ordered arrays compatible with polysomes (Fig. 1E), suggesting that RAV-bound ribosomes are translationally active (29).

Figure 1. Identification of RAVs in primary neurons by cryo-CLEM and cryo-ET.

(A, B) Cryo-CLEM shows ER marker mNeon-KDEL localizes to discrete puncta in the periphery of primary hippocampal neurons. A cryo–tomographic slice with (A) and without (B) overlay of an epifluorescence image with mNeon-KDEL fluorescence (in green). Scale bars, 200 nm. (C) Average of 164 manually selected subvolumes of RAV-bound particles. Reference-free alignment provides a structure consistent with an 80S mammalian ribosome. (D) Subtomogram average of a validated mammalian 80S ribosome structure (EMD-0529; down-sampled to 32Å) by cryo-ET, indicating the RAV-bound subvolumes are 80S ribosomes. (E) Isosurface of the RAV in Panel B featuring subtomogram averaged RAV-bound 80S ribosomes mapped back to their original positions. Enlarged views indicate an ordered polysome arrangement of RAV-associated ribosomes.

Human brain imaging confirms the presence of RAVs in neurons

To determine whether our findings in primary rodent neurons could be translated to human brain, we imaged human cortex via focused ion beam-scanning electron microscopy volume electron microscopy (FIB-SEM VEM), which similarly revealed the presence of RAVs (Fig. S2, Movie S2). 3D reconstruction of the brain volume demonstrated a representative RAV with membrane-bound electron-dense ribosome-like particles, measuring at a mean diameter of 33.57 ± 4.61 nm, consistent with the diameter of mammalian 80S ribosomes (~30 nm) (Fig. S2B–S2D). The membrane-bound particles exhibited a spiral arrangement indicative of the polysomal organization of actively translating ribosomes (29) (Fig. S2). Overall ultrastructural preservation of organelles was confirmed by segmenting and reconstructing networks of intact ER, including RER alongside Golgi apparatus and mitochondria within this neuronal cell body (Fig. S3, Movie S3). These results strongly suggest that the neuronal RAVs observed in the human brain volume were not due to postmortem degradation of RER.

Characterization of RAV dynamics in axons and dendrites

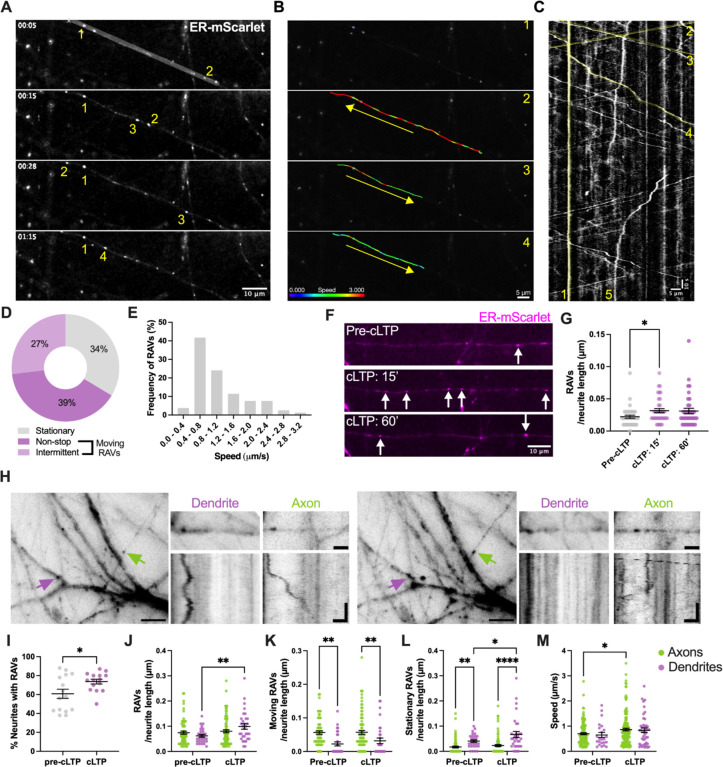

We next comprehensively examined the dynamic trafficking of RAVs in primary rodent neurons. We used live-cell wide-field microscopy to image primary rat cortical neurons expressing the ER marker, ER-mScarletI (30). We observed well-defined ER-mScarletI-labeled puncta indicative of RAVs mainly in the neuron periphery, analogous to our mNeon-KDEL-labeled puncta (Fig. 2A–2C, Movie S4). Notably, we identified two primary populations of RAVs: actively moving versus stationary RAVs. The majority of RAVs were in motion (66% of total RAVs), while the remainder were stationary (34%) (Fig. 2D). Among the moving RAVs, we observed different patterns of motion. Kymograph analysis revealed that, while 59% of RAVs underwent processive movement, 41% displayed non-continuous or intermittent motion characterized by pausing for variable periods of time along their paths (Fig. 2A–2C). Analysis of RAV mobility demonstrated a wide distribution of speeds ranging from 0.2–3.2 μm/s (Fig. 2E), with a mean speed of 0.86 ± 0.07 μm/s, consistent with microtubule-mediated transport (31). In addition, RAVs moved bidirectionally in anterograde and retrograde directions (Fig. 2A–2C, Movie S4). Moreover, similar to previous descriptions of axonal transport and endosomal trafficking in axons (32), fast (>0.5 μm/s) versus slow (<0.5 μm/s) velocities may reflect distinct RAV-associated trafficking functions, including differences in the trafficking of specific cargos.

Fig. 2. RAV dynamics in the neuron periphery.

(A) Representative time-lapse images demonstrate the dynamics of ER-mScarletI-labeled RAVs (numbered 1–4) over time along a peripheral neurite belonging to a primary cortical neuron (DIV11–12). Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Frame-by-frame velocity measurements of the RAVs in (A). Each of the 4 highlighted RAVs (1–4) demonstrates different dynamics as indicated by the color-coded velocity range: stationary (1), fast (2), moderate (3), and slow (4) velocities, respectively. Arrows specify the overall direction of movement along the neurite. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) Kymograph of the segmented neurite from (A). Highlighted lines (in yellow) indicate movements of the RAVs (1–4) featured in (A) and (B) (1–4) across a 5-min timespan. (5) indicates a RAV with intermittent movement prior to stopping in place. Scale bar, 5 μm, 10 s imaging. (D) Relative proportion of moving (non-stop and intermittent) versus stationary RAVs in the periphery (n=119 in 30 neurites). (E) Distribution of average speeds of moving RAVs (n=79 tracks, 30 neurites). (F) Representative images showing increased local recruitment and accumulation of RAVs (indicated by arrows) within cortical neurites in response to chemical long-term potentiation (cLTP). Scale bars, 10 μm. (G) Quantification of total RAV numbers. Mean ± SEM; *p<0.05, Friedman test. (H) Comparison of RAVs in axons versus dendrites in mouse primary hippocampal neurons. Scale bar, 5 μm. Images on the right represent enlarged views of representative regions of interest. Corresponding kymographs showing a combination of stationary and moving RAVs in axons and dendrites. Scale bar in enlarged image, 2 μm. Scale bar kymographs, 2 μm, 20 s. (I) Percentage of neurites (axons and dendrites) with and without RAVs. n = 208 neurites pre-cLTP, n = 209 cLTP. (J-M) Quantitative analyses of RAV dynamics in mouse hippocampal axons and dendrites in response to cLTP. Analyses include, total RAV numbers (J), number of moving RAVs (K), number of stationary RAVs (L) and RAV speed (M). Mean ± SEM; *p<0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, Two-way ANOVA. n= 66 axons (pre-cLTP), n= 29 dendrites (pre-cLTP), n = 87 axons (cLTP) and n= 31 dendrites (cLTP).

RAVs respond distinctly to neuronal stimulation in axons versus dendrites

Substantial evidence demonstrates enhanced local protein synthesis in distal processes which drives plasticity in response to neuronal activity (11, 13, 15, 33). We asked whether neuronal stimulation alters RAV trafficking using a chemically-induced long-term potentiation (cLTP) paradigm. In primary cortical neurons, we found a significant increase in the density of RAVs in neurites within 15 min of cLTP induction – a 1.5-fold increase in RAV density under cLTP conditions (0.032 ± 0.003 RAVs/μm) compared to basal conditions prior to cLTP stimulation (0.022 ± 0.003 RAVs/μm) (Fig. 2F, 2G, Table S1). There was no further change in RAV numbers after 60 min of cLTP (0.031 ± 0.004 RAVs/μm) (Fig. 2F, 2G, Table S1). Additionally, cLTP did not modify the average speed of moving RAVs in the periphery of cortical neurons (Table S1). In the absence of significant differences between 15 and 60 min of cLTP, we focused primarily on the earlier time point.

We next validated our results in primary hippocampal neurons, which also exhibited an increase in RAV numbers after 15 min of cLTP compared to pre-stimulation (Table S2). Indeed, we detected significantly more RAV-containing neurites (12.87 ± 4.32% increase) in response to cLTP (Fig. 2I). In dendritic processes, we discovered an activity-driven increase in total RAV numbers/μm after cLTP (cLTP: 0.099 ± 0.011; pre-cLTP: 0.062 ± 0.005 RAVs/μm) (Fig. 2J, Table S3). This was primarily accounted for by a net increase in the number of stationary RAVs (cLTP: 0.067± 0.012; pre-cLTP: 0.040 ± 0.005 RAVs/μm) with no accompanying changes in mobile RAV numbers within distal dendrites (cLTP: 0.032 ± 0.084; pre-cLTP: 0.022 ± 0.006 RAVs/μm) (Fig. 2J, 2K, Table S3). These data indicate that previously mobile RAVs from elsewhere in the neuron may enter these dendrites, becoming stationary within this initial window of cell stimulation. The increased numbers of stationary RAVs in dendrites following cLTP also suggests that RAVs may engage in activity-driven translation at local sites, consistent with earlier work indicating that mRNAs pause or localize in response to activity (14, 15).

In addition to RAVs in dendrites, our live-imaging revealed numerous RAVs moving in thin, spineless processes distal from the cell body consistent with axons (Fig. 2H). We similarly observed this via cryo-CLEM, indicating that mNeon-KDEL puncta identified in axonal processes were indeed RAVs (Fig. S4). To further confirm that RAVs are present in axons, we examined the expression of mNeon-KDEL in mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons (DRGs), which exclusively possess axons but not dendrites. We identified RAVs in distal DRG axons (Fig. S5, Movie S5), validating our data.

Comparisons of RAV dynamics in axons versus dendrites revealed that, unlike dendrites, in axons, there was no cLTP-induced change either in total RAV density (cLTP: 0.080 ± 0.006 RAVs/μm; pre-cLTP: 0.074 ± 0.061 RAVs/μm) or in the density of moving (cLTP: 0.057 ± 0.006; pre-cLTP: 0.056 ± 0.050 RAVs/μm) versus stationary RAVs (cLTP: 0.023 ± 0.004; pre-cLTP: 0.017 ± 0.004 RAVs/μm) (Fig. 2J–2L, Table S3). However, we observed that cLTP caused RAV acceleration specifically in axons, but not in dendrites (Fig. 2M, Table S3). We posit that cLTP-induced increases in axonal RAV speed ensure that RAVs reach their intended local destinations in a timely manner given that some axons may be >1 meter in length (1). Taken together, these data suggest that RAV trafficking in axons and dendrites is sensitive to neuronal stimulation, albeit in ways distinct to each subcompartment.

RAVs drive activity-dependent local translation

Local activity-driven translation in the neuron periphery requires spatial and temporal coordination of the trafficking of both mRNAs and ribosomes (1, 3). However, many questions remain concerning the precise relationships between mRNAs and the ribosomal machinery in axons and dendrites. We therefore examined co-trafficking between endogenous β-actin mRNA alongside oScarlet-KDEL-labeled-RAVs in primary hippocampal neurons (Fig. S6A, S6B, Movie S6). We found ~8% of β-actin mRNAs and RAVs co-localized/co-trafficked over time (Fig. S6C). We next examined whether cell stimulation would modify RAV-mRNA interactions. Surprisingly, cLTP did not significantly alter the frequency of these associations (cLTP: 13.93 ± 4.36%; pre-cLTP: 7.98 ± 3.24%) (Fig. S6C). These data suggest that RAVs may be equally engaged under basal and stimulated conditions for local translation of β-actin mRNA, although we posit that this may not be the case for other mRNAs.

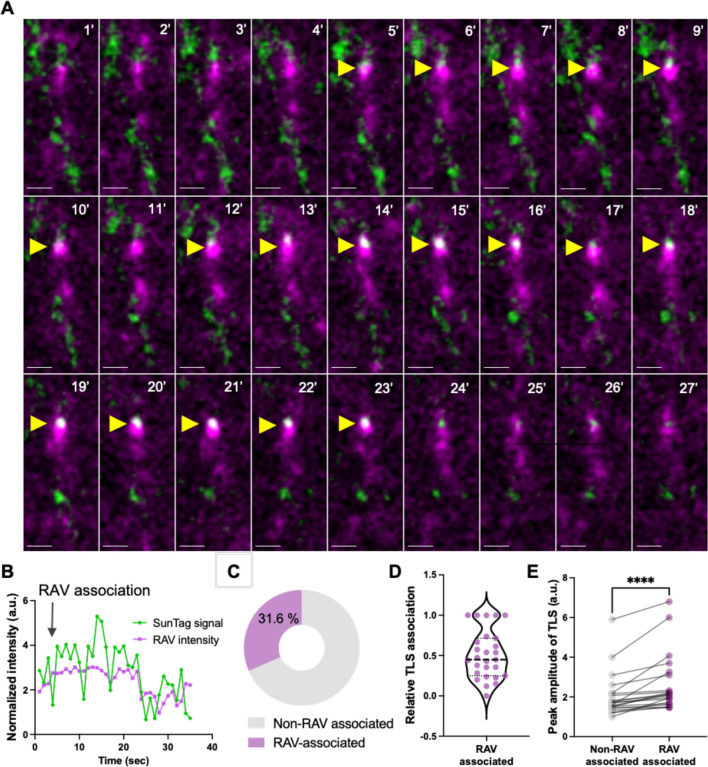

To directly evaluate whether RAVs serve as platforms for local activity-driven translation in distal neurites, we conducted single-molecule imaging of nascent peptides (SINAPS) via the SunTag reporter alongside oScarlet-KDEL-labeled RAVs. We co-transduced SunTag reporter, scFv-sfGFP, and oScarlet-KDEL in primary hippocampal neurons followed by cLTP stimulation. Translation sites (TLS) were defined as discrete fluorescent foci brighter than diffusing proteins, resulting from the rapid binding of superfolder GFP-labeled single-chain antibody fragments (scFv) to the SunTag epitope as nascent peptides were synthesized. We found that stationary RAVs mostly colocalized with TLS in dendrites following cLTP (Fig. 3A–3C, Movie S7), indicating that RAVs actively translated mRNAs in response to neuronal stimulation. Quantitation showed that 31.6% of TLS were directly associated with RAVs (Fig. 3C). Moreover, along the time course of translation, RAVs were associated with TLS for 50.87 ± 0.06% of the sampling time (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, RAVs exhibited directed movement and accumulated near pre-existing TLS, likely contributing to the ribosomal pool required for local translation (Fig. S7, Movie S8). Indeed, tracking the integrated intensity of individual TLS associated with RAVs demonstrated greater peak SunTag amplitude (2.64 ± 0.32 a.u.) compared to non-RAV-associated TLS (2.04 ± 0.24 a.u.), suggesting that RAVs boost local translational output (Fig. 3E). These results show that RAVs act as translation platforms at local sites in mature neurons.

Fig. 3: RAV association boosts activity-dependent local translation.

(A) Time-lapse imaging of primary mouse hippocampal neurons expressing oScarlet-KDEL (magenta) and SunTag (green) reporter. In response to cLTP, there is increasing overlap (white) between oScarlet-KDEL-labeled RAVs and translation sites (TLS) in specific dendritic segments (yellow arrows). Scale bar, 1 μm. (B) Intensity trace of oScarlet-KDEL and SunTag fluorescent signals across time following cLTP. Black arrow indicates when RAV associates with the SunTag signal, and a corresponding increase in SunTag intensity observed. Note that the dissociation of RAV leads to a corresponding decrease of SunTag signal. (C) Frequency of RAV-SunTag association across different dendrites, n =19 dendrites from 2 independent experiments. (D) RAV association with the TLS relative to path trajectory. Each dot represents a translation site, n = 27, Mean = 0.5 ± 0.06. (E) Quantification of peak SunTag fluorescence intensity in the presence or absence of RAV association during the entire trajectory of translation. n = 21 trajectories. P < 0.001, Wilcoxon test.

By actively promoting translation of a cytosolic protein via the SunTag mRNA reporter system, our results showed that RAVs are capable of protein synthetic activities beyond the production of membrane and secretory proteins. These data are consistent with growing evidence that ribosomes associated with RER can also translate cytosolic proteins (34). A significant fraction of mRNAs encoding cytosolic proteins are found on ER membranes and associate with RER-bound ribosomes (34). Indeed, in HEK293 cells, as much as 75% of RER-associated translation is directed towards the synthesis of cytosolic proteins (34). This suggests that RER, and RAVs by extension, can serve as a more generalized platform for translation of a broader variety of mRNAs than previously appreciated. Further, bringing together mRNAs and ribosomes to RAV membranes may allow the RAV to serve as a critical local hub to boost both the efficiency and regulation of local protein synthesis at TLS. Additionally, it is notable that translation also occurred independently of RAVs. We therefore posit that RAV-independent local protein synthesis may be carried out by other cellular components, including free ribosomes or other organelles such as endosomes that have been associated with translation (35). Nevertheless, the higher amplitude of RAV-associated TLS in response to neuronal activity suggests that RAVs boost translation in distal neuronal processes. Overall, our data point to RAVs as a key component of the machinery responsible for activity-driven local translation in neurons.

In vivo imaging of RAVs

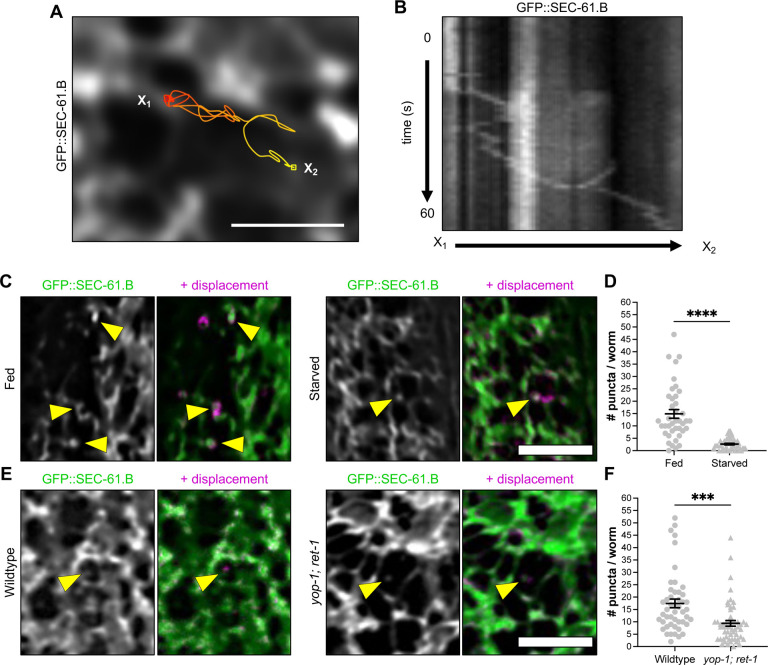

We extended our findings within an in vivo context using the C. elegans model given its genetic tractability and transparency, which offers the ability to directly monitor intracellular dynamics throughout the entire animal (36). We labeled RER in adult worms using eGFP fused to SEC61.B, a central component of the ER translocon complex (eGFP::SEC-61.B). As in mammalian neurons, we observed dynamic RAV-like puncta in epidermal cells (Fig. 4A, 4B, Movie S9). This is consistent with our previous work in mammalian cells showing Sec61b present in RAVs (27). Since our data showed changes in neuronal activity impact RAV numbers and their trafficking, we determined whether this is similarly the case within intact worms. Changes in nutritional state can act as potent modulators of metabolic activity in worms (37). Indeed, the transition from starved to fed states boosts cellular activity, while shifting from fed to starved states diminishes activity over time (37, 38). We therefore predicted that the shift in cellular metabolic activity in response to a change from fed to starved states would impact the number of RAV-like puncta in epidermal cells of whole living wild-type worms. Indeed, we identified a substantial 5.6-fold reduction in the number of RAV-like structures in starved animals compared with previously fed worms (Fig. 4C, 4D). These data further point to the sensitivity of RAVs to changes in cellular activity in vivo.

Fig. 4. RAV-like structures in C. elegans require ER-shaping membrane proteins and respond to nutritional state.

(A) Annotated path of a RAV-like structure in the epidermis of an adult C. elegans expressing rough ER reporter GFP::SEC-61.B. Scale, 2.5 μm. (B) Kymograph of RAV-like structure from Panel A. (C) ER and RAV-like structures in epithelial cells of fed and starved animals. Arrows indicate RAV-like structures, highlighted by their displacement with time (magenta). Scale, 5 μm. (D) The number of puncta per worm in control (n=40) and starved (n=49) worms. (E) The ER and RAV-like structures in control (wild type/N2) and ER mutant (yop-1; ret-1) animals. Arrows indicate RAV-like structures, highlighted by their displacement with time (magenta). Scale, 5 μm. (F) The number of puncta per worm in wild type control (n=48) and mutant (n=54) worms. There is a significant decrease in RAV-like puncta in ER mutant worms compared to wild type. Two-tailed t-test; Mean ± SEM; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Tubular ER shaping proteins drive in vivo RAV generation

Finally, the mechanisms of RAV formation from the ER network have yet to be defined. The ER is a highly dynamic organelle with a complex arrangement of sheets that transition into increasingly narrow tubular matrices in the cell periphery (39–42). This network of tubules and sheets is continuously remodeled through the contributions of the ubiquitously expressed reticulon and REEP/DP1/Yop1p families of ER-shaping proteins (39, 43–45). Members of these two families localize to ER membranes where they form oligomeric scaffolds that are both necessary and sufficient to generate and stabilize sites of membrane curvature required for ER tubule formation (44, 46). Since RAVs emerge from three-way junctions of the tubular ER network (27), we postulated that members of the reticulon and REEP/DP1/Yop1p families promote the alterations in local ER membrane curvature required for RAV formation. However, it has been challenging to directly interrogate the respective contributions of these ER-sculpting proteins in mammalian cells due to functional redundancy (45). For example, mammals express four reticulon paralogs (RTN1–4) with each possessing several isoforms (45). Therefore, a major advantage of our C. elegans model is its expression of a sole reticulon ortholog (RET-1) (47), enabling us to avoid potential compensation from remaining reticulon isoforms. Just as importantly, earlier work demonstrated that RET-1 and YOP-1, the C. elegans ortholog of DP1, are redundantly required for maintenance of the ER tubule network where depletion of either protein alone had no effects on ER structure (48). As a result, we combined a CRISPR/Cas9-generated YOP-1 nonsense mutation with a preexisting RET-1 deletion to determine whether these two ER-shaping proteins impact RAV generation and maintenance in vivo. By monitoring eGFP::SEC-61.B-labeled RAV-like puncta in the mutant (yop-1; ret-1) worms, we discovered that simultaneous loss of RET-1 and YOP-1 significantly decreased numbers of RAV-like puncta (Fig. 4E, 4F). The presence of residual RAVs in the yop-1; ret-1 double mutants also suggests that additional players likely contribute to RAV formation and maintenance. Overall, these findings suggest that the combination of reticulon and DP-1/Yop1 ER-shaping proteins play key roles in RAV formation in vivo. Importantly, our results connecting RAVs and ER shaping proteins may also shed new light on the molecular mechanisms by which reticulons modulate structural plasticity in axons and dendrites in the mammalian nervous system. Members of the reticulon family such as RTN4 (alternatively known as Nogo-A), are expressed in brain regions strongly involved in synaptic plasticity, including the hippocampus and neocortex and are implicated in the structural changes underlying learning and memory (49, 50). Moreover, within adult rat spinal motor neurons, RTN4 associates with RER and polysomes (51). Together, these data raise the possibility that our findings in C. elegans are conserved across species and further connect RAVs with the molecular machinery of neuronal plasticity.

In conclusion, our findings underscore the ability of RAVs to promote activity-dependent local translation, providing new insights into the mechanisms underlying protein synthesis away from the neuronal cell body. Furthermore, these results suggest that RAVs act differently in dendrites and axons, raising important questions about the molecular mechanisms driving compartment-specific differences. These findings pave the way for future research to: 1) identify the specific mRNAs translated by RAVs within distinct neuronal subcompartments; 2) elucidate the factors responsible for control of activity-driven RAV dynamics and translation, and 3) define how RAV-mediated events impact synaptic plasticity. Finally, our data provide a novel perspective on the molecular players responsible for RAV formation, offering new targets for the potential modulation of activity-driven synaptic plasticity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms. Mary Brady for expert assistance with movie generation. We are also grateful to Drs. James Olds, David Lewis, and Jamie Moy for technical assistance and helpful discussions.

Funding:

This work was supported by The Pittsburgh Foundation (ZF), the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Formula Fund (ZF), the Baszucki Family Foundation (ZF), NIH R21MH122961 (SD), R01NS083085 (SD), and R01NS122784 (MSG). Cryo-ET studies were supported by NIH R35GM122588 (GJJ). The N2 strain was provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40OD010440). Some C. elegans deletion mutations used in this work were provided by the C. elegans Reverse Genetics Core Facility at the University of British Columbia, which is a part of the International C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium and is funded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research, Genome Canada, Genome B.C., the Michael Smith Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by The Pittsburgh Foundation (ZF), the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Formula Fund (ZF), the Baszucki Family Foundation (ZF), NIH R21MH122961 (SD), R01NS083085 (SD), and R01NS122784 (MSG). Cryo-ET studies were supported by NIH R35GM122588 (GJJ). The N2 strain was provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40OD010440). Some C. elegans deletion mutations used in this work were provided by the C. elegans Reverse Genetics Core Facility at the University of British Columbia, which is a part of the International C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium and is funded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research, Genome Canada, Genome B.C., the Michael Smith Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to ZF and SD.

References and Notes

- 1.Holt C. E., Martin K. C., Schuman E. M., Local translation in neurons: visualization and function. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26, 557–566 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez-Moya S. M., Bauer K. E., Kiebler M. A., Meet the players: local translation at the synapse. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 7, 84 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piper M., Holt C., RNA translation in axons. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20, 505–523 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hafner A. S., Donlin-Asp P. G., Leitch B., Herzog E., Schuman E. M., Local protein synthesis is a ubiquitous feature of neuronal pre- and postsynaptic compartments. Science 364, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garner C. C., Tucker R. P., Matus A., Selective localization of messenger RNA for cytoskeletal protein MAP2 in dendrites. Nature 336, 674–677 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgin K. E. et al. , In situ hybridization histochemistry of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in developing rat brain. J Neurosci 10, 1788–1798 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassell G. J. et al. , Sorting of beta-actin mRNA and protein to neurites and growth cones in culture. J Neurosci 18, 251–265 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cajigas I. J. et al. , The local transcriptome in the synaptic neuropil revealed by deep sequencing and high-resolution imaging. Neuron 74, 453–466 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glock C. et al. , The translatome of neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das S., Vera M., Gandin V., Singer R. H., Tutucci E., Intracellular mRNA transport and localized translation. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 22, 483–504 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hacisuleyman E. et al. , Neuronal activity rapidly reprograms dendritic translation via eIF4G2:uORF binding. Nat Neurosci, (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber K. M., Kayser M. S., Bear M. F., Role for rapid dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Science 288, 1254–1257 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju W. et al. , Activity-dependent regulation of dendritic synthesis and trafficking of AMPA receptors. Nat Neurosci 7, 244–253 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon Y. J. et al. , Glutamate-induced RNA localization and translation in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E6877–e6886 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das S., Lituma P. J., Castillo P. E., Singer R. H., Maintenance of a short-lived protein required for long-term memory involves cycles of transcription and local translation. Neuron 111, 2051–2064.e2056 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahren B., Islet G protein-coupled receptors as potential targets for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 8, 369–385 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steward O., Wallace C. S., Lyford G. L., Worley P. F., Synaptic activation causes the mRNA for the IEG Arc to localize selectively near activated postsynaptic sites on dendrites. Neuron 21, 741–751 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shigeoka T. et al. , Dynamic Axonal Translation in Developing and Mature Visual Circuits. Cell 166, 181–192 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steward O., Levy W. B., Preferential localization of polyribosomes under the base of dendritic spines in granule cells of the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci 2, 284–291 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostroff L. E. et al. , Shifting patterns of polyribosome accumulation at synapses over the course of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Hippocampus 28, 416–430 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biever A. et al. , Monosomes actively translate synaptic mRNAs in neuronal processes. Science 367, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yperman K., Kuijpers M., Neuronal endoplasmic reticulum architecture and roles in axonal physiology. Molecular and cellular neurosciences 125, 103822 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y. et al. , Contacts between the endoplasmic reticulum and other membranes in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aakalu G., Smith W. B., Nguyen N., Jiang C., Schuman E. M., Dynamic visualization of local protein synthesis in hippocampal neurons. Neuron 30, 489–502 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D. O. et al. , Synapse- and stimulus-specific local translation during long-term neuronal plasticity. Science 324, 1536–1540 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu B., Eliscovich C., Yoon Y. J., Singer R. H., Translation dynamics of single mRNAs in live cells and neurons. Science 352, 1430–1435 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter S. D. et al. , Ribosome-associated vesicles: A dynamic subcompartment of the endoplasmic reticulum in secretory cells. Sci Adv 6, eaay9572 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen M. et al. , A complete data processing workflow for cryo-ET and subtomogram averaging. Nat Methods 16, 1161–1168 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christensen A. K., Bourne C. M., Shape of large bound polysomes in cultured fibroblasts and thyroid epithelial cells. Anat Rec 255, 116–129 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chertkova A. O. et al. , Robust and Bright Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Markers for Highlighting Structures and Compartments in Mammalian Cells. bioRxiv, 160374 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banks R. A. et al. , Motor processivity and speed determine structure and dynamics of microtubule-motor assemblies. eLife 12, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guedes-Dias P., Holzbaur E. L. F., Axonal transport: Driving synaptic function. Science 366, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutton M. A., Wall N. R., Aakalu G. N., Schuman E. M., Regulation of dendritic protein synthesis by miniature synaptic events. Science 304, 1979–1983 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reid D. W., Nicchitta C. V., Diversity and selectivity in mRNA translation on the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 16, 221–231 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cioni J. M. et al. , Late Endosomes Act as mRNA Translation Platforms and Sustain Mitochondria in Axons. Cell 176, 56–72.e15 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meneely P. M., Dahlberg C. L., Rose J. K., Working with Worms: Caenorhabditis elegans as a Model Organism. Current Protocols Essential Laboratory Techniques 19, e35 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baugh L. R., Hu P. J., Starvation Responses Throughout the Caenorhabditiselegans Life Cycle. Genetics 216, 837–878 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan K. T., Luo S. C., Ho W. Z., Lee Y. H., Insulin/IGF-1 receptor signaling enhances biosynthetic activity and fat mobilization in the initial phase of starvation in adult male C. elegans. Cell Metab 14, 390–402 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuentes L. A., Marin Z., Tyson J., Baddeley D., Bewersdorf J., The nanoscale organization of reticulon 4 shapes local endoplasmic reticulum structure in situ. J Cell Biol 222, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nixon-Abell J. et al. , Increased spatiotemporal resolution reveals highly dynamic dense tubular matrices in the peripheral ER. Science 354, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu J., Rapoport T. A., Fusion of the endoplasmic reticulum by membrane-bound GTPases. Seminars in cell & developmental biology 60, 105–111 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S., Tukachinsky H., Romano F. B., Rapoport T. A., Cooperation of the ER-shaping proteins atlastin, lunapark, and reticulons to generate a tubular membrane network. eLife 5, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu J. et al. , Membrane proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum induce high-curvature tubules. Science 319, 1247–1250 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shibata Y. et al. , The reticulon and DP1/Yop1p proteins form immobile oligomers in the tubular endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 283, 18892–18904 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Y. S., Strittmatter S. M., The reticulons: a family of proteins with diverse functions. Genome Biol 8, 234 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang N., Rapoport T. A., Reconstituting the reticular ER network - mechanistic implications and open questions. Journal of cell science 132, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwahashi J. et al. , Caenorhabditis elegans reticulon interacts with RME-1 during embryogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 293, 698–704 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Audhya A., Desai A., Oegema K., A role for Rab5 in structuring the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 178, 43–56 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zagrebelsky M. et al. , Nogo-A regulates spatial learning as well as memory formation and modulates structural plasticity in the adult mouse hippocampus. Neurobiology of learning and memory 138, 154–163 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.GrandPré T., Nakamura F., Vartanian T., Strittmatter S. M., Identification of the Nogo inhibitor of axon regeneration as a Reticulon protein. Nature 403, 439–444 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin W. L. et al. , Intraneuronal localization of Nogo-A in the rat. J Comp Neurol 458, 1–10 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to ZF and SD.