Abstract

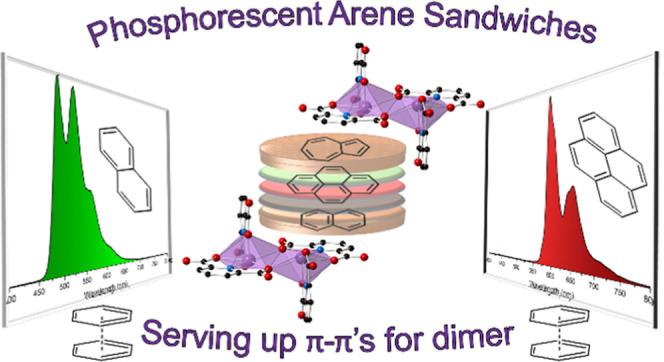

Three novel bismuth–organic compounds, with the general formula [Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2]·(arene)·2H2O (H2PDC = 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylic acid; arene = pyrene, naphthalene, and azulene), that consist of neutral dinuclear Bi-pyridinedicarboxylate complexes and outer coordination sphere arene molecules were synthesized and structurally characterized. The structures of all three phases exhibit strong π–π stacking interactions between the Bi-bound PDC/HPDC and outer sphere organic molecules; these interactions effectively sandwich the arene molecules between bismuth complexes and thereby prevent molecular vibrations. Upon UV irradiation, the compounds containing pyrene and naphthalene displayed red and green emission, respectively, with quantum yields of 1.3(2) and 30.8(4)%. The emission was found to originate from the T1 → S0 transition of the corresponding arene and result in phosphorescence characteristic of the arene employed. By comparison, the azulene-containing compound displayed very weak blue-purple phosphorescence of unknown origin and is a rare example of T2 → S0 emission from azulene. The pyrene- and naphthalene-containing compounds both display radioluminescence, with intensities of 11 and 38% relative to bismuth germanate, respectively. Collectively, these results provide further insights into the structure–property relationships that underpin luminescence from Bi-based materials and highlight the utility of Bi–organic molecules in the realization of organic emission.

Short abstract

Bismuth compounds containing arene molecules “sandwiched” in the outer coordination sphere via π−π interactions displayed phosphorescence and radioluminescence characteristic of the arene molecule. Previous studies highlighted the importance of the π−π interactions, while this study emphasizes the relative unimportance of hydrogen bonding toward achieving phosphorescence.

Introduction

Luminescent materials are vital to life in the 21st century and such recognition has led to significant innovations in the design of materials for use in electronic displays1−8 and sensors.9−13 With respect to the latter, there exist a wide range of analytes of interest for sensing applications. Of particular note are recent advances in the detection of toxic or carcinogenic chemicals such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).14−16 While every application that employs luminescent compounds has specific criteria, materials with tunable luminescent properties that are afforded via simple compositional changes are particularly attractive as they can be used as multifunctional materials to meet the demands of a wide range of applications. For example, lanthanide-based phosphors have been synthesized that can act as white-light-emitting diodes, sensors, or anticounterfeiting tags by altering the composition of the material.17−19 However, in addition to functionality, the cost and toxicity of the structural components must be kept in mind.

Bismuth has become an attractive element toward the design of functional materials due to its nontoxicity as well as its unique electronic and structural properties.20−27 For example, Vogler and colleagues proposed that bismuth and other main group metals with closed-shell ns2 electron configurations could undergo similar photoluminescent transitions to those observed for the d10 metals.28,29 In fact, more recent work has shown that bismuth–organic compounds have even more versatility as luminescent materials than originally hypothesized; bismuth has been shown to participate in the frontier orbital electronic transitions directly or indirectly by promoting intraligand transitions through its unique coordination chemistry. Notably, bismuth-based metal-to-ligand charge-transfer (MLCT) materials in which the metal directly participates in the electronic transitions have displayed emission across the visible spectrum and exhibited other attractive properties such as mechanochromic luminescence.30−33 In 2021, for example, Marshak et al. reported a bismuth tris(benzo[h]quinoline) (bzq) compound, Bi(bzq)3, that displayed 3MLCT emission in the blue region.34 The electronic structure of this compound was found to be similar to a lead perovskite, methylammonium lead iodide, and the composition of the material was analogous to Ir(bzq)3, a phosphorescent emitter of interest for organic light-emitting diodes.35,36 In a related vein, bismuth halides have shown a propensity to display halide-metal-to-ligand charge transfer (XMLCT) that allows for even more diverse emissive pathways and properties.37−39 Further electronic participation from bismuth toward photoluminescence can arise from its metal-based transitions, particularly the 3P1 → 1S0 transition and the forbidden 3P0 → 1S0 transition.40

Bismuth-based materials have also been shown to act as structural scaffolds or hosts to achieve photoluminescence originating from an organic fluorophore. In 2010 and 2011, zur Loye and colleagues reported a series of Bi-2,5-pyridinedicarboxylate coordination polymers that displayed intraligand transitions and yielded blue, green, and white light emission.41−43 Additionally, bismuth–organic materials have been used as hosts for lanthanide ions, with doping occurring via site substitution.44−51 Such materials leverage the similar ionic radii and coordination chemistry of Bi3+ and the Ln3+ ions to achieve characteristic Ln3+ emission with just a fraction of the rare-earth elements required for an analogous homometallic Ln3+ phase. Furthermore, the heavy-atom effect imparted by bismuth has been exploited to realize efficient intersystem crossing and long-lived, room-temperature phosphorescence.52 For example, a series of phosphorescent bismuth-halide materials bridged through the rigid ligand, bipyrimidine, were reported with lifetimes as long as 11.36 ms at 77 K.53 The compounds were synthesized from ionic liquids and the resulting photophysical properties were tunable based on the ionic liquid employed as it incorporated into the structure. Related bismuth-halide materials have similarly shown phosphorescence originating from 2,2′-bipyridyl derivatives; these compounds exhibited long lifetimes and X-ray luminescence, with the latter alluding to the potential application of bismuth–organic materials as X-ray scintillators.54,55

Given the promising developments in bismuth-based luminescent materials design, our group has sought to further elucidate structure–property relationships in these phases. Of particular interest is the role that noncovalent interactions have in the photophysical properties of bismuth–organic materials. To understand these effects, our initial work was motivated by previous work in 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylate (PDC) ligand systems56 and specifically the observation of a common dimeric motif.57−59 We hypothesized that such units could be utilized to study the effects of noncovalent interactions between the bismuth–organic complexes and outer coordination sphere fluorophores on photophysical properties. Recently, we detailed the synthesis and characterization of a bismuth–organic structure in which stabilization of 1,10-phenanthrolinium (Hphen) via hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions led to long-lived room-temperature phosphorescence characteristic of Hphen triplet emission.60 Furthermore, in a subsequent report, we highlighted the impact of π–π interactions on luminescent properties in a series of analogous structures with phen-derivatives; phosphorescence from the phen-derivatives was only achieved when strong π–π interactions occurred between PDC and the phen-derivatives and in the absence of π–π interactions due to steric effects, weak fluorescence was observed.61 Thus, by exploiting strong π–π interactions, this system yields predictable phosphorescence with the emission dictated solely by the identity of the N-heterocycle employed during synthesis. Yet, the effect that hydrogen bonding had on the emissive properties remained unclear. To this end, in this work, we sought to understand the impact of hydrogen bonding on the phosphorescence of the outer sphere fluorophore. Herein, we describe the synthesis, structure, photoluminescent, and radioluminescent properties of three analogous compounds with the general formula [Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2]·[fluorophore]·2H2O, where H2PDC is 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylic acid and [fluorophore] is pyrene, naphthalene, and azulene. Notably, these fluorophores are PAHs incapable of hydrogen bonding and thus, together with previous work, provide important insights into the role of noncovalent interactions including hydrogen bonding and π–π stacking interactions on Bi–organic phosphorescence.

Results

Structure Descriptions

[Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2]·(Pyrene)·2H2O (1)

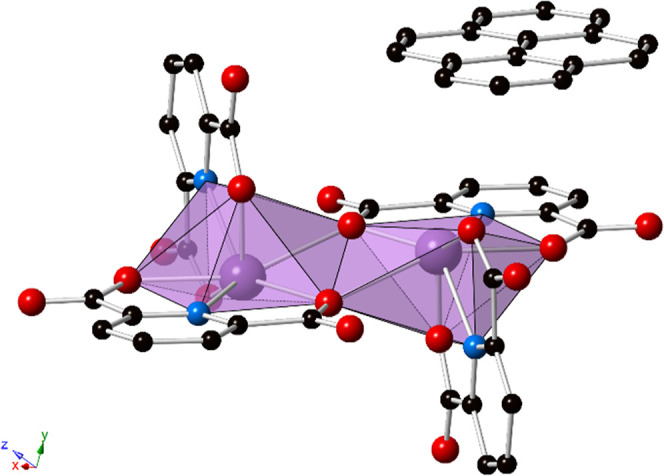

The asymmetric unit of compound 1 consists of one crystallographically unique bismuth ion that is coordinated to a tridentate, doubly deprotonated PDC, a tridentate, singly deprotonated HPDC, half of a pyrene molecule, and one water molecule; application of the inversion symmetry about the pyrene yields one pyrene molecule per unit cell. As shown in Figure 1, the bismuth center is bridged by the doubly deprotonated PDC to a symmetry-equivalent site to form dimeric structural units. The bismuth metal centers are seven-coordinate and exhibit a hemidirected coordination geometry, with an open face indicative of a stereochemically active 6s2 lone pair. A pyrene molecule exists in the outer coordination sphere and occupies the space afforded by the open Bi coordination site. The Bi–O distances range from 2.189(3) to 2.655(3) Å and the Bi–N distances are 2.409(3) and 2.440(3) Å. The significant variance between Bi–O bond lengths is characteristic of the 6s2 stereochemically active lone pair, with the shortest bond occurring trans to the lone pair.

Figure 1.

Polyhedral representation of 1. The structure consists of Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2 dimers, with pyrene in the outer coordination sphere. Strong π–π stacking interactions exist between the bridging PDC and the pyrene. Purple = bismuth, blue = nitrogen, red = oxygen, and black = carbon atoms. Hydrogen atoms and lattice water molecules have been omitted for clarity.

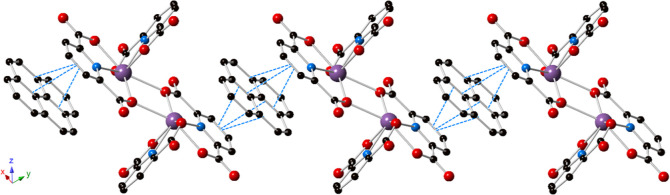

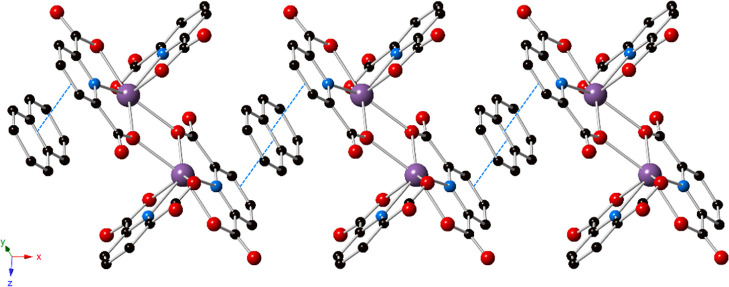

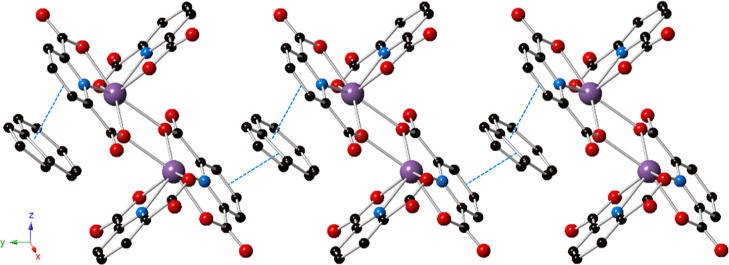

As shown in Figure 2, π–π stacking interactions between the PDC of one dimer, the outer coordination pyrene, and a PDC of a dimer in the next unit cell (PDC···pyrene···PDC interactions) result in propagation of the dimeric units into 1-D supramolecular chains. The centroid···centroid distances are 3.569(3), 3.600(3), and 3.861(3) Å, with slip angles of 19.3, 20.8, and 29.2°, respectively. Additionally, there are OHPDC–H···Owater hydrogen-bonding interactions with a DHPDC···Awater distance of 2.493(5) Å and D–H···A angle of 178(8)°. Similarly, there are Owater–H···OPDC interactions with Dwater···APDC distances of 2.743(5) and 2.722(4) Å and angles of 162(5) and 168(4)°, respectively. The hydrogen-bonding interactions bridge the 1-D chains into an overall 3-D extended network (Figures S4 and S5). Furthermore, the closest Bi···centroid distance is 3.889 Å with a β angle of 22.2°, which is consistent with a lone-pair–π interaction between bismuth and the pyrene. Such lone-pair–π interactions have been noted to occur in some main group metals with an ns2 electron configuration (Sb3+, Bi3+, etc.).62 Additional nonclassical C–H···O interactions are also present between PDCs with a D–H···A distance of 3.216(5) Å and a bond angle of 127°.

Figure 2.

Ball and stick representation of 1 showing the 1-D chains formed by PDC···pyrene···PDC π–π stacking interactions (blue dotted lines, depicting centroid···centroid interactions). Purple = bismuth, blue = nitrogen, red = oxygen, and black = carbon atoms. Hydrogen atoms and lattice water molecules have been omitted for clarity.

[Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2]·(Naphthalene)·2H2O (2)

The structure of 2 (Figure 3) is built from the same bismuth-PDC scaffold as that described for 1.

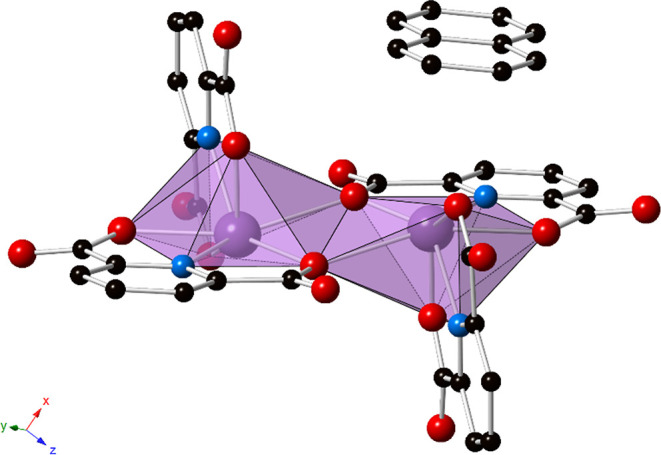

Figure 3.

Polyhedral representation of 2. The structure is built from the same Bi-PDC dimer as that observed in 1; however, naphthalene is present in the outer coordination sphere and exhibits strong π–π stacking interactions with the bridging PDC. Purple = bismuth, blue = nitrogen, red = oxygen, and black = carbon atoms. Hydrogen atoms and lattice water molecules have been omitted for clarity.

The asymmetric unit consists of one crystallographically unique bismuth ion that is coordinated to a tridentate, doubly deprotonated PDC, a tridentate, singly deprotonated HPDC, half of a naphthalene molecule, and one water molecule; application of the inversion symmetry about the naphthalene yields one naphthalene molecule per unit cell. The bismuth metal center displays a hemidirected coordination environment with the stereochemically active 6s2 lone pair directed toward the large open coordination site. The Bi–O distances range from 2.180(4) to 2.705(4) Å and the Bi–N distances are 2.434(4) and 2.462(4) Å.

As shown in Figure 4, the structure of 2 consists of 1-D chains that extend down the [100] via π–π stacking interactions between PDC···naphthalene···PDC rings. The centroid···centroid distances are 3.556(4) and 3.555(4) Å with slip angles of 23.9°. These are effectively the same PDC···naphthalene interaction, generated through symmetry, and hence the two nearly identical interaction parameters. Additionally, there are OHPDC–H···Owater hydrogen-bonding interactions as in 1 with a DHPDC···Awater distance of 2.488(5) Å and D–H···A angle of 168(3)°, as well as Owater–H···OPDC interactions with Dwater···APDC distances of 2.755(5) and 2.741(5) Å and angles of 168(6) and 164(5)°, respectively. The hydrogen-bonding interactions bridge the 1-D chains into an extended 3-D network (Figures S6 and S7). Additionally, there exist potential LP–π interactions between bismuth and the naphthalene, with a Bi···centroid distance of 3.579 Å and β angle of 10.2°. Nonclassical C–H···O interactions are also present with distances of 3.185(6), 3.173(6), 3.366(6), and 3.458(7) Å and bond angles of 123, 127, 158, and 166°, respectively, although the latter two interactions are relatively long and weak.

Figure 4.

Ball and stick representation of 2 showing the 1-D chains that extend down the [100] by PDC···naphthalene···PDC π–π stacking interactions (blue dotted lines). Purple = bismuth, blue = nitrogen, red = oxygen, and black = carbon atoms. Hydrogen atoms and lattice water molecules have been omitted for clarity.

[Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2]·(Azulene)·2H2O (3)

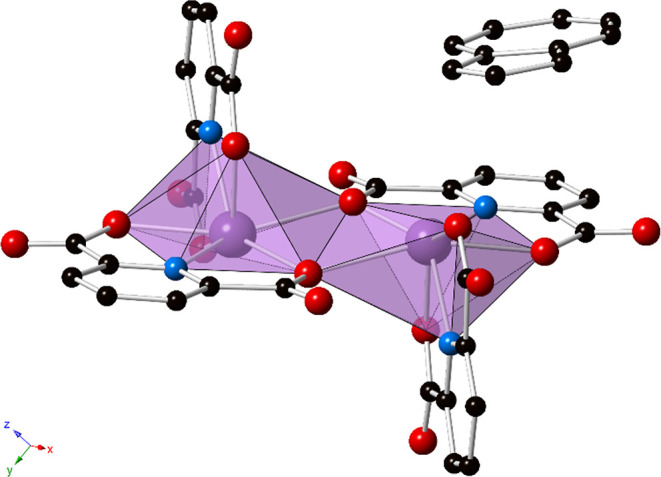

Compound 3 is isomorphous with 2 and consists of the same [Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2] dimeric unit (Figure 5). The asymmetric unit consists of one crystallographically unique bismuth ion, a doubly deprotonated PDC, a singly deprotonated HPDC, half of an azulene molecule, and one water molecule; application of the inversion symmetry about the azulene yields one azulene molecule per unit cell. The bismuth ions are seven-coordinate with a hemidirected coordination geometry. The Bi–O distances range from 2.196(3) to 2.705(3) Å and the Bi–N distances are 2.438(3) and 2.454(4) Å.

Figure 5.

Polyhedral representation of 3. Outer sphere azulene displays strong π–π stacking interactions with the bridging PDC. Purple = bismuth, blue = nitrogen, red = oxygen, and black = carbon atoms. Hydrogen atoms, lattice water molecules, and disorder of the azulene have been omitted for clarity.

An azulene molecule is present in the outer coordination sphere. The azulene is disordered over two sites, accounting for the two orientations of the asymmetric aromatic hydrocarbon. As depicted in Figure 6, strong π–π stacking interactions between PDC···azulene···PDC rings result in supramolecular 1-D chains. The centroid···centroid distance, between PDC and the five-membered ring on azulene, is 3.369(4) Å with a slip angle of 14.8°. The 1-D chains are further connected into a 3-D supramolecular structure through hydrogen bonding, as shown in Figures S8 and S9. The OHPDC–H···Owater hydrogen-bonding interaction has a DHPDC···Awater distance of 2.482(5) Å and D–H···A angle of 165(6)°, and the Owater–H···OPDC interaction exhibits Dwater···APDC distances of 2.754(4) and 2.766(5) Å with angles of 167(6) and 156(6)°, respectively. Nonclassical C–H···O interactions may be present with a distance of 3.189(5) Å and bond angle of 126°.

Figure 6.

Ball and stick representation of 3 highlighting the 1-D chains formed via PDC···azulene···PDC π–π interactions (blue dotted lines). Purple = bismuth, blue = nitrogen, red = oxygen, and black = carbon atoms. Hydrogen atoms, lattice water molecules, and disorder of the azulene are not shown for clarity.

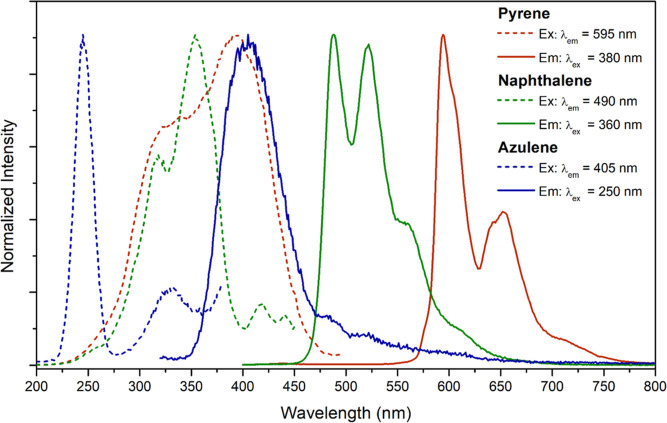

Photoluminescence

All three compounds display room-temperature photoluminescence in the solid state of varying intensity; normalized excitation and emission plots for 1–3 are shown in Figure 7. The CIE 1931 coordinates were calculated for each emission spectrum and the chromaticity of each compound is presented in Figure S16. Compound 1 emits in the red region between 570 and 750 nm with a maximum at 595 nm (16,807 cm–1) upon excitation at 380 nm. The presence of additional local maxima at 655 nm (15,267 cm–1) and a smaller shoulder at 715 nm (13,986 cm–1) is attributed to vibronic coupling from an organic emitter, with peak separations of 1540 and 1281 cm–1, respectively. The excitation spectrum for the emission at 595 nm is very broad; there are two main peaks at 390 and 335 nm, and the profile extends into the visible region. The emission spectrum for 1 is consistent with pyrene phosphorescence and has been described previously, most commonly for solution-state studies that have examined host–guest properties.63−69 The luminescence decay spectrum for emission at 595 nm fit well with a biexponential decay function, indicating the presence of two distinct lifetimes of 465.5 and 128.9 μs (Figure S13). The shorter lifetime is attributed to direct singlet excitation of the pyrene molecule, followed by intersystem crossing and emission from the pyrene triplet state. The excitation spectrum matches well with that of pyrene in the solid state (Figure S17), providing evidence for partial contribution from direct excitation of pyrene. The solid-state quantum yield (Φ) for 1 was 1.3(2)%.

Figure 7.

Normalized excitation (dashed lines) and emission (solid lines) spectra for pyrene (1; red), naphthalene (2; green), and azulene (3; blue).

Compound 2 emitted intense green light between 450 and 750 nm upon excitation at 360 nm. The maximum emission wavelength was 490 nm (20,408 cm–1), and splitting resulted in additional local maxima at 520 (19,231 cm–1) and 555 nm (18,018 cm–1), again indicative of vibronic coupling from an organic emitter with coupling energies of 1177 and 1213 cm–1, respectively. The excitation spectrum was broad with two main peaks: a maximum around 360 nm and another peak centered at 320 nm. The luminescence decay spectrum for 2 recorded at 490 nm fit well with a single exponential decay function, yielding a lifetime of 485.5 μs (Figure S14). The emission profile is attributed to phosphorescence from the outer coordination naphthalene and is consistent with previous reports.69−71 The quantum yield for 2 was 30.8(4)%.

Compound 3 displayed very weak emission at 405 nm upon excitation at 250 nm; albeit the lamp was only weakly emitting at 250 nm and may contribute to the low emission intensity. Nonetheless, as compared to 1 and 2, the emission spectrum does not exhibit splitting indicative of vibronic coupling. Rather, the emission spectrum exhibits a comparatively sharp band, with an excitation maximum around 250 nm and a significantly less intense peak centered at approximately 330 nm. The decay spectrum for the emission of 3 at 405 nm fit well with a single exponential decay function with a lifetime of 111.2 μs (Figure S15). Quantum yields were not collected for 3 given the prohibitively weak emission intensity.

Radioluminescence

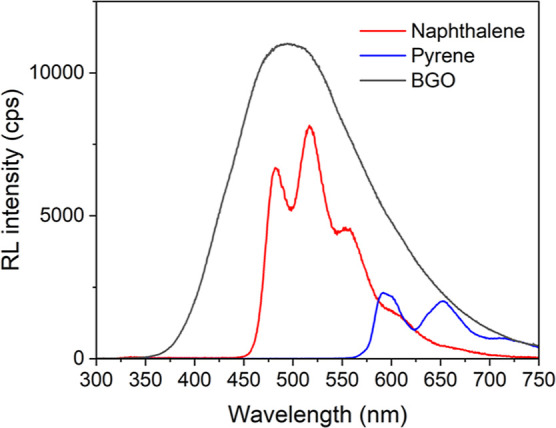

Compounds 1 and 2 display luminescence upon irradiation with X-rays, as shown in Figure 8. Bismuth and other heavy atoms can absorb ionizing radiation and eject photoelectrons which may result in the emission of light in a process called X-ray luminescence or radioluminescence.71−75 The emission displayed from both compounds is effectively identical to that observed via photoexcitation; 1 shows characteristic pyrene phosphorescence and 2 shows characteristic naphthalene phosphorescence. This is consistent with a previous study wherein radioluminescence was observed from phosphorescent bismuth–organic compounds, with the emission dictated by the triplet-state energies of the outer coordination sphere phenanthroline derivatives employed.61

Figure 8.

Radioluminescence spectra for 1 (blue), 2 (red), and BGO (black). The spectra were integrated and the relative intensities were compared to that of BGO.

The integrated intensities of the radioluminescence spectra were compared to that of bismuth germanate (BGO), a common bismuth-based standard for radioluminescence intensity comparisons. Compound 1 displayed a relative intensity of 11% compared to BGO, while compound 2 displayed a relative intensity of 38% compared to BGO powder. While these relative intensities clearly pale in intensity to BGO, there is novelty in radioluminescence with tunable properties dictated by the organic arene ligand. Indeed, examples of bismuth–organic scintillators are limited.

Discussion

Compounds 1–3 all display photoluminescence at room temperature in the solid state. Both 1 and 2 display phosphorescence characteristic of the outer coordination sphere arene molecules.63−68,70,76 Importantly, these compounds display strong π–π stacking interactions yet contain no hydrogen-bonding interactions with the outer coordination arene molecule. In a previous study, we reported a similar bismuth–organic dimer with an outer coordination N-heterocycle, Hphen; the compound exhibited characteristic Hphen phosphorescence at room temperature in the solid state.60 Much like compounds 1–3, the Hphen engaged in strong π–π stacking interactions with the PDC of the bismuth complex but also acted as a hydrogen bond donor to a nitrate anion on the bismuth complex. The role that the noncovalent interactions had on the luminescence was not entirely clear. Absence of hydrogen bonding between the Bi complex and the outer sphere fluorophore in 1–3 shows that such H-bonding interactions have little effect on the lifetimes and efficiencies of these phosphorescent materials; compound 2 in particular displays a higher quantum yield (Φ = 30.8%) than that observed for the Hphen analogue (Φ = 27.4%).

Previously, we proposed that the outer coordination fluorophore was plausibly sensitized via triplet–triplet energy transfer.61 We proposed that protonation of the fluorophores (i.e., Hphen and 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthrolinium) allowed for a stepwise electron and hole transfer due to the presence of a metastable, neutrally charged intermediate state; when the fluorophore was not ionized (i.e., 2,9-dichloro-1,10-phenanthroline), the sensitization could occur through a concerted energy-transfer mechanism, leading to shorter lifetimes. The work presented herein is further consistent with a concerted energy-transfer mechanism. Both 1 and 2 display lifetimes (465.5 and 485.5 μs, respectively) consistent with the previously reported neutrally charged [Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2(H2O)]·(Cl2Phen) compound which showed Cl2Phen phosphorescence, with a lifetime of 534 μs. The presence of strong π–π stacking interactions appears to be the defining structural feature to achieve phosphorescence in this system, and the presence or absence of an ionized fluorophore controls the lifetime.

The efficiency of the emission is likely dictated by the energy of the emitting T1 state of the fluorophore relative to the bismuth complex. This is consistent with the inefficient emission (Φ = 1.3%) observed for 1, which likely results from the significant Stoke’s shift of the material; excitation occurred at 380 nm and the emission maximum was centered at 595 nm. Compound 2, by comparison, had an excitation maximum of 360 nm and an emission maximum of 490 nm. This suggests that inefficient energy transfer occurs between the bismuth complex and pyrene; there is poor energy matching between the donor and acceptor excited states resulting in significant nonradiative relaxation. A similar trend can be observed in the radioluminescence intensities; 1 displayed a relative intensity to BGO of 11%, while 2 displayed a relative intensity of 38%. This is likely the result of inefficient energy transfer to the pyrene molecule compared to naphthalene. These values are consistent with a previous report wherein bismuth complexes synthesized with 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline and 2,9-dichloro-1,10-phenanthroline displayed radioluminescence with relative intensities of 33 and 52% compared to BGO powder, respectively.61

Azulene was chosen as an outer coordination arene molecule due to its unique optical and electronic properties.77 Azulene was the first molecule discovered to display S2 → S0 emission,78 breaking Kasha’s rule which states that “the emitting electronic level of a given multiplicity is the lowest excited level of the multiplicity”.79 While T2 → S0 emission has been reported from organic molecules before, it is rare and to the best of our knowledge has not been reported for azulene.80 This system, which achieves triplet emission from the outer coordination arene ligand, seemed like the ideal opportunity to achieve azulene phosphorescence. While the long lifetime of 3 (111.2 μs) is consistent with phosphorescence, the emission profile of 3 does not exhibit features indicative of vibronic coupling as observed for 1 and 2. The peak at 405 nm is slightly red-shifted from previous reports of S2 → S0 emission from azulene, with peaks around 375 and 390 nm, again consistent with a red shift expected for T2 → S0 emission. However, the shift is small.81 Thus, the origin of the emission at 405 nm remains unclear, with several feasible pathways including azulene, the bismuth complex, or some charge-transfer state on the whole bismuth–organic structure. It should be noted that the emission intensity of 3 is very weak—no significant emission can be observed with the naked eye.

Conclusions

Three novel bismuth–organic complexes with arenes (pyrene, naphthalene, and azulene) in the outer coordination sphere were synthesized. These hydrocarbons were stabilized via strong π–π stacking interactions between the PDC of the bismuth complex and the arene. Compounds 1 and 2 containing pyrene and naphthalene, respectively, displayed characteristic phosphorescence and radioluminescence from the outer coordination sphere arene molecule while 3, the azulene analogue, displayed very weak emission from an unknown high-energy excited state. This work follows previous reports wherein phosphorescence from N-heterocycles was achieved in a similar manner, but importantly, this work highlights that the presence of hydrogen bonding has little effect on the lifetimes or efficiencies of the phosphorescence. Similarly, this work promotes the possibility of achieving phosphorescence from a much larger catalog of arene ligands, allowing for the tunability of emissive properties simply by changing the fluorophore identity.

Experimental Methods

Materials

Bi(NO3)3·5H2O (Fisher, 99.2%), 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylic acid (Acros Organics, 99%), nitric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, 70%), azulene (Alfa Aesar, 99%), pyrene (Aldrich, 99%), naphthalene (Aldrich, ≥99%), 2-propanol (Fisher Chemical), methylene chloride (Fisher Chemical), and ethanol (Fisher Chemical, 90%) were used as received. Nanopure water was used for all experiments (≤0.05 μS; Millipore, USA).

Synthesis

[Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2]·(Pyrene)·2H2O (1)

2,6-Pyridinedicarboxylic acid (0.0334 g; 0.20 mmol), pyrene (0.0051 g; 0.025 mmol), and ethanol (1.5 mL) were added to a 7.5 mL glass vial and sonicated for 5 min in a bath sonicator. Bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (0.0243 g; 0.05 mmol) was dissolved in 2 M nitric acid (0.5 mL) in a separate vial and diluted with an additional aliquot of water (1 mL). The ethanolic solution was then gently layered on top of the aqueous solution. The resulting mixture was capped and allowed to sit at room temperature. After 2 days, yellow plate-like crystals that exhibited red luminescence upon UV irradiation had precipitated on the bottom of the vial. The mother liquor was decanted and the crystals were rinsed with water, ethanol, and two aliquots of dichloromethane. A phase-pure bulk powder was isolated using the same method by stirring the ethanolic and aqueous solutions instead of layering, followed by gravity filtration of the product. Yield = 64% (based on Bi). Elemental analysis for C44H28Bi2N4O18 Calcd (Obs.): C, 40.08 (39.76); H, 2.14 (2.25); N, 4.25 (4.25%).

[Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2]·(Naphthalene)·2H2O (2)

2,6-Pyridinedicarboxylic acid (0.0334 g; 0.20 mmol), naphthalene (0.0768 g; 0.60 mmol), and 2-propanol (1.5 mL) were added to a 7.5 mL glass vial and sonicated for 10 min in a bath sonicator. In a separate vial, bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (0.0243 g; 0.05 mmol) was dissolved in 2 M nitric acid (0.5 mL) and diluted with an additional aliquot of water (1 mL). The ligand solution was then gently layered on top of the aqueous solution. The resulting mixture was capped and allowed to sit at room temperature. After 3 days, colorless plate-like crystals that exhibited green luminescence upon UV irradiation were observed. The mother liquor was decanted and the crystals were rinsed with water, ethanol, and two aliquots of dichloromethane. Yield = 75% (based on Bi). Elemental analysis for C38H26Bi2N4O18 Calcd (Obs.): C, 36.67 (36.57); H, 2.11 (2.21); N, 4.50 (4.41%).

[Bi2(HPDC)2(PDC)2]·(Azulene)·2H2O (3)

Compound 3 was synthesized using the same method as that described for 2, replacing naphthalene with azulene (0.0256 g; 0.20 mmol). Dark-blue plate-like crystals were obtained as a pure phase. Yield = 83% (based on Bi). Elemental analysis for C38H26Bi2N4O18 Calcd (Obs.): C, 36.67 (37.02); H, 2.11 (2.25); N, 4.50 (4.23%).

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction

Single crystals of 1–3 were isolated from the bulk samples, coated in N-paratone, and mounted on a MiTeGen micromount. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected on a Bruker D8 QUEST diffractometer at 100(2) K using an IuS X-ray source (Mo Kα radiation; λ = 0.71073 Å) and a Photon 100 detector. The diffraction data were integrated utilizing the SAINT software within APEX3.82,83 A multiscan absorption correction method was applied in SADABS.84 Intrinsic phasing was used to solve all three structures in SHELXT and structures were refined through full-matrix least-squares on F2 with the SHELXL software in shelXle64.85,86 Details of the refinement are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Crystallographic Refinement Details for 1–3.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW (g/mol) | 1318.66 | 1244.59 | 1244.59 |

| T (K) | 100(2) | 100(2) | 100(2) |

| λ (K α) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| μ (mm–1) | 8.775 | 9.686 | 9.660 |

| crystal system | triclinic | triclinic | triclinic |

| space group | P1̅ | P1̅ | P1̅ |

| a (Å) | 9.2325(2) | 9.3216(3) | 9.2435(7) |

| b (Å) | 11.1406(3) | 9.3590(3) | 9.6020(7) |

| c (Å) | 11.2691(3) | 11.9812(3) | 11.7706(9) |

| α (deg) | 76.880(1) | 111.959(2) | 92.797(2) |

| β (deg) | 71.456(1) | 93.182(2) | 110.752(2) |

| γ (deg) | 68.088(1) | 106.182(2) | 107.347(2) |

| volume (Å3) | 1011.76(5) | 915.92(5) | 918.43(12) |

| Z | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Rint | 0.0348 | 0.0442 | 0.0529 |

| R (I > 2σ) | 0.0216 | 0.0304 | 0.0215 |

| wR2 | 0.0461 | 0.0636 | 0.0538 |

| GooF | 1.107 | 1.030 | 1.064 |

| residual density max and min (e/Å3) | 0.96 and −0.74 | 1.56 and −1.17 | 2.10 and −1.49 |

| CCDC no. | 2252259 | 2252257 | 2252258 |

Photoluminescence

Luminescence spectra were collected on a Horiba PTI QM-400 fluorometer on ground samples of 1–3 pressed between two quartz microscope slides. Wavelengths of 380, 360, and 250 nm were used to excite the samples, representing the maximum excitation wavelengths of 1–3, respectively. Spectral widths of 3, 1, and 7 nm were used for 1–3, respectively. Luminescence spectra for pyrene and naphthalene were collected using similar conditions (Figures S17 and S18). Lifetime measurements were collected using a Xenon pulse lamp source with a 100 Hz lamp frequency. Decay spectra were fit with exponential decay functions using the OriginPro 8.5 software. A 400 nm long-pass filter was utilized to prevent harmonic peaks resulting from the excitation source for 1 and 2, and a 320 nm long-pass filter was utilized for 3. CIE chromaticity coordinates were calculated from the emission spectra using the PTI FelixGX software. Quantum yield measurements were collected in triplicate with 2 nm spectral widths for 1 and 2. Crystals of 1 and 2 were ground in dry KBr (1:50 ratio of sample/KBr) and placed in a Teflon powder holder under ambient conditions. The holder was then placed within an 8.9 cm integrating sphere with a Spectralon fluoropolymer coating. Blank absorption and emission reference spectra were collected using the Teflon sample holder filled with dried KBr.

Radioluminescence

Radioluminescence measurements were carried out using a customer-designed configuration of the Freiberg Instruments Lexsyg Research spectrofluorometer equipped with a Varian Medical Systems VF-50J X-ray tube with a tungsten target. The X-ray source was coupled with a Crystal Photonics CXD-S10 photodiode for continuous radiation intensity monitoring. The light emitted by the sample was collected by an Andor Technology SR-OPT-8024 optical fiber connected to an Andor Technology Shamrock 163 spectrograph coupled to a cooled (−80 °C) Andor Technology DU920P-BU Newton CCD camera (spectral resolution of ∼0.5 nm/pixel). Radioluminescence was measured under continuous X-ray irradiation (W lines and bremsstrahlung radiation; 40 kV, 1 mA) with an integration time of 1 or 5 s. Powders filled ∼8 mm diameter, 0.5 mm deep cups thus allowing for relative radioluminescence intensity comparison between different samples. BGO powder [Alfa Aesar Puratronic, 99.9995% (metal basis)] was used as a reference. Spectra were automatically corrected using the spectral response of the system determined by the manufacturer. Comparison was done by integrating the spectra from 350 to 750 nm, with percentages being given in relation to the integrated signal of the BGO powder.

Characterization Methods

Powder X-ray diffraction data were collected on ground samples of compounds 1–3 (Cu Kα; λ = 1.542 Å) on a Rigaku Miniflex diffractometer from 3 to 40° 2θ with a step speed of 1°/min (Figures S10–S12). Combustion elemental analysis data were collected on the bulk phases of 1–3 with a PerkinElmer Model 2400 Elemental Analyzer. Thermogravimetric analysis was collected using a TA Instruments Q50 Thermogravimetric Analyzer with flowing N2 with a temperature ramp rate of 5 °C/min (Figures S19–S21).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under grants NSF DMR-2203658 and NSF DMR-1653016.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c00606.

Crystallographic refinement details, thermal ellipsoid plots, packing diagrams, powder X-ray diffraction patterns, phosphorescence decay plots, and a table of supramolecular interactions (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Huang Y.; Hsiang E.-L.; Deng M.-Y.; Wu S.-T. Mini-LED, micro-LED and OLED displays: present status and future perspectives. Light: Sci. Appl. 2020, 9 (1), 105. 10.1038/s41377-020-0341-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P.; Singh S.; Gupta I.; Kumar V.; Singh D. Preparation and luminescence behaviour of perovskite LaAlO3:Tb3+ nanophosphors for innovative displays. Optik 2022, 267, 169709. 10.1016/j.ijleo.2022.169709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Li C.; Ren Z.; Yan S.; Bryce M. R. All-organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3 (4), 18020. 10.1038/natrevmats.2018.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Zhu M.; Sun J.; Shi W.; Zhao Z.; Wei X.; Huang X.; Guo Y.; Liu Y. A self-assembled 3D penetrating nanonetwork for high-performance intrinsically stretchable polymer light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34 (27), 2201844. 10.1002/adma.202201844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.; Wang Z.; Meng T.; Yuan T.; Ni R.; Li Y.; Li X.; Zhang Y.; Tan Z.; Lei S.; Fan L. Red phosphorescent carbon quantum dot organic framework-based electroluminescent light-emitting diodes exceeding 5% external quantum efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (45), 18941–18951. 10.1021/jacs.1c07054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z.; Zhang X.; Wang H.; Huang C.; Sun H.; Dong M.; Ji L.; An Z.; Yu T.; Huang W. Wide-range lifetime-tunable and responsive ultralong organic phosphorescent multi-host/guest system. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12 (1), 3522. 10.1038/s41467-021-23742-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M.; Saeed M. H.; Zhang S.; Wei H.; Gao Y.; Zou C.; Zhang L.; Yang H. Luminescence enhancement, encapsulation, and patterning of quantum dots toward display applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32 (13), 2109472. 10.1002/adfm.202109472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Kuang J.; Wu P.; Zong Z.; Li Z.; Wang H.; Li J.; Dai P.; Zhang K. Y.; Liu S.; et al. Manipulating electroluminochromism behavior of viologen-substituted iridium(III) complexes through ligand engineering for information display and encryption. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34 (5), 2107013. 10.1002/adma.202107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. Y.; Si Y.; Yang J. S.; Zhang C.; Han Z.; Luo P.; Wang Z. Y.; Zang S. Q.; Mak T. C. W. Ligand engineering to achieve enhanced ratiometric oxygen sensing in a silver cluster-based metal-organic framework. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 3678. 10.1038/s41467-020-17200-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.; Le T.; Huang K.; Han G. Enzymatic enhancing of triplet-triplet annihilation upconversion by breaking oxygen quenching for background-free biological sensing. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12 (1), 1898. 10.1038/s41467-021-22282-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian S.; Wang Z.; Zuo Z.; Wang X.; Wang Q.; Yuan X. Engineering luminescent metal nanoclusters for sensing applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 451, 214268. 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Sun B.; Su Z.; Hong G.; Li X.; Liu Y.; Pan Q.; Sun J. Lanthanide-MOFs as multifunctional luminescent sensors. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9 (13), 3259–3266. 10.1039/D2QI00682K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D.; Yu K.; Han X.; He Y.; Chen B. Recent progress on porous MOFs for process-efficient hydrocarbon separation, luminescent sensing, and information encryption. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58 (6), 747–770. 10.1039/D1CC06261A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Tian X.; Li Y.; Yang C.; Huang Y.; Nie Y. Rapid and sensitive screening of multiple polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by a reusable fluorescent sensor array. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127694. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comnea-Stancu I. R.; van Staden J. K. F.; Stefan-van Staden R.-I. Review—trends in recent developments in electrochemical sensors for the determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from water resources and catchment areas. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168 (4), 047504. 10.1149/1945-7111/abf260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosental M.; Coldman R. N.; Moro A. J.; Angurell I.; Gomila R. M.; Frontera A.; Lima J. C.; Rodríguez L. Using room temperature phosphorescence of gold(I) complexes for PAHs sensing. Molecules 2021, 26 (9), 2444. 10.3390/molecules26092444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan G.; Jia R.-Q.; Wu W.-L.; Li B.; Wang L.-Y. Highly pH-stable Ln-MOFs as sensitive and recyclable multifunctional materials: luminescent probe, tunable luminescent, and photocatalytic performance. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22 (1), 323–333. 10.1021/acs.cgd.1c00956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z.-H.; Zhang P.-F.; Ma L.-L.; Deng Y.-X.; Yang G.-P.; Wang Y.-Y. Lanthanide-organic frameworks with uncoordinated lewis base sites: tunable luminescence, antibiotic detection, and anticounterfeiting. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61 (16), 6101–6109. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.; Luo L.; Li W.; Yu J. S.; Du P. Designing tunable luminescence in Ce3+/Eu2+-codoped Ca8Zn(SiO4)4Cl2 phosphors for white light-emitting diode and optical anti-counterfeiting applications. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 26, 101038. 10.1016/j.mtchem.2022.101038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fabini D. H.; Seshadri R.; Kanatzidis M. G. The underappreciated lone pair in halide perovskites underpins their unusual properties. MRS Bull. 2020, 45 (6), 467–477. 10.1557/mrs.2020.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z.; Zhang Z.; Xiu J.; Song H.; Gatti T.; He Z. A critical review on bismuth and antimony halide based perovskites and their derivatives for photovoltaic applications: recent advances and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8 (32), 16166–16188. 10.1039/D0TA05433J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X.; Zhang Z. Bismuth-based photocatalytic semiconductors: introduction, challenges and possible approaches. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2016, 423, 533–549. 10.1016/j.molcata.2016.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen N.; Wang Z.; Jin J.; Gong L.; Zhang Z.; Huang X. Phase transitions and photoluminescence switching in hybrid antimony(III) and bismuth(III) halides. CrystEngComm 2020, 22 (20), 3395–3405. 10.1039/D0CE00057D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adonin S. A.; Sokolov M. N.; Fedin V. P. Polynuclear halide complexes of Bi(III): from structural diversity to the new properties. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 312, 1–21. 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.-X.; Li G. Bi(III) MOFs: syntheses, structures and applications. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8 (3), 572–589. 10.1039/D0QI01055C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia H.; Guo J.; Savory C. N.; Rush M.; James D. I.; Dey A.; Chen C.; Bucar D.-K.; Clarke T. M.; Scanlon D. O.; et al. Exploring bismuth coordination complexes as visible-light absorbers: synthesis, characterization, and photophysical properties. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63 (1), 416–430. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c03290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter A.; Newkome G. R.; Schubert U. S. The chemistry of the s- and p-block elements with 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine ligands. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11 (2), 342–399. 10.1039/D3QI01245J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler A.; Paukner A.; Kunkely H. Photochemistry of coordination compounds of the main group metals. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1990, 97, 285–297. 10.1016/0010-8545(90)80096-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkely H.; Paukner A.; Vogler A. Optical metal-to-ligand charge-transfer of 2,2′-bipyridyl complexes of antimony(III) and bismuth(III). Polyhedron 1989, 8 (24), 2937–2939. 10.1016/S0277-5387(00)86294-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg J. R.; Wehner T.; Matthes P. R.; Sure R.; Grimme S.; Heine J.; Müller-Buschbaum K. Bismuth as a versatile cation for luminescence in coordination polymers from BiX3/4,4′-bipy: understanding of photophysics by quantum chemical calculations and structural parallels to lanthanides. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 7669–7681. 10.1039/c8dt00642c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine J.; Wehner T.; Bertermann R.; Steffen A.; Muller-Buschbaum K. 2∞[Bi2Cl6(pyz)4]: a 2D-pyrazine coordination polymer as soft host lattice for the luminescence of the lanthanide ions Sm3+, Eu3+, Tb3+, and Dy3+. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53 (14), 7197–7203. 10.1021/ic500295r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D.-W.; Chen W.-T.; Wang Y.-F. Photoluminescence, semiconductive properties and theoretical calculation of a novel bismuth biimidazole compound. Luminescence 2017, 32 (2), 201–205. 10.1002/bio.3168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma O.; Mercier N.; Allain M.; Meinardi F.; Forni A.; Botta C. Mechanochromic luminescence of N,N′-dioxide-4,4′-bipyridine bismuth coordination polymers. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20 (12), 7658–7666. 10.1021/acs.cgd.0c00872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer L. A.; Pearce O. M.; Maharaj F. D. R.; Brown N. L.; Amador C. K.; Damrauer N. H.; Marshak M. P. Open for bismuth: main group metal-to-ligand charge transfer. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60 (14), 10137–10146. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c03818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodate S.; Suzuka I. Assignments of lowest triplet state in Ir complexes by observation of phosphorescence excitation spectra at 6 K. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 45 (1S), 574. 10.1143/JJAP.45.574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grzelak I.; Orwat B.; Kownacki I.; Hoffmann M. Quantum-chemical studies of homoleptic iridium(III) complexes in OLEDs: fac versus mer isomers. J. Mol. Model. 2019, 25 (6), 154. 10.1007/s00894-019-4035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayscue R. L. 3rd; Vallet V.; Bertke J. A.; Real F.; Knope K. E. Structure-property relationships in photoluminescent bismuth halide organic hybrid materials. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60 (13), 9727–9744. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adcock A. K.; Ayscue R. L. 3rd; Breuer L. M.; Verwiel C. P.; Marwitz A. C.; Bertke J. A.; Vallet V.; Real F.; Knope K. E. Synthesis and photoluminescence of three bismuth(III)-organic compounds bearing heterocyclic N-donor ligands. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49 (33), 11756–11771. 10.1039/D0DT02360D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A. W.; Wheaton A. M.; Nicholas A. D.; Barnes F. H.; Patterson H. H.; Pike R. D. Iodobismuthate(III) and iodobismuthate(III)/iodocuprate(I) complexes with organic ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 2017 (43), 4990–5000. 10.1002/ejic.201701052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feyand M.; Koppen M.; Friedrichs G.; Stock N. Bismuth tri- and tetraarylcarboxylates: crystal structures, in situ X-ray diffraction, intermediates and luminescence. Eur. J. Chem. 2013, 19 (37), 12537–12546. 10.1002/chem.201301139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wibowo A. C.; Smith M. D.; zur Loye H.-C. Structural diversity of metal-organic materials containing bismuth(III) and pyridine-2,5-dicarboxylate. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11 (10), 4449–4457. 10.1021/cg200639b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wibowo A. C.; Smith M. D.; zur Loye H. C. A new Kagome lattice coordination polymer based on bismuth and pyridine-2,5-dicarboxylate: structure and photoluminescent properties. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47 (26), 7371–7373. 10.1039/c1cc11720c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wibowo A. C.; Vaughn S. A.; Smith M. D.; Zur Loye H. C. Novel bismuth and lead coordination polymers synthesized with pyridine-2,5-dicarboxylates: two single component “white” light emitting phosphors. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49 (23), 11001–11008. 10.1021/ic1014708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adcock A. K.; Gibbons B.; Einkauf J. D.; Bertke J. A.; Rubinson J. F.; de Lill D. T.; Knope K. E. Bismuth(III)-thiophenedicarboxylates as host frameworks for lanthanide ions: synthesis, structural characterization, and photoluminescent behavior. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47 (38), 13419–13433. 10.1039/C8DT02920B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adcock A. K.; Marwitz A. C.; Sanz L. A.; Lee Ayscue R.; Bertke J. A.; Knope K. E. Synthesis, structural characterization, and luminescence properties of heteroleptic bismuth-organic compounds. CrystEngComm 2021, 23 (46), 8183–8197. 10.1039/D1CE01242H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batrice R. J.; Ayscue R. L. 3rd; Adcock A. K.; Sullivan B. R.; Han S. Y.; Piccoli P. M.; Bertke J. A.; Knope K. E. Photoluminescence of visible and NIR-emitting lanthanide-doped bismuth-organic materials. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24 (21), 5630–5636. 10.1002/chem.201706143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan L.; Li J.; Luo X.; Li G.; Liu Y. Three novel bismuth-based coordination polymers: synthesis, structure and luminescent properties. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2017, 85, 70–73. 10.1016/j.inoche.2017.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song L.; Tian F.; Liu Z. Lanthanide doped metal-organic frameworks as a ratiometric fluorescence biosensor for visual and ultrasensitive detection of serotonin. J. Solid State Chem. 2022, 312, 123231. 10.1016/j.jssc.2022.123231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurugan A.; Cheetham A. K. Anionic metal-organic frameworks of bismuth benzenedicarboxylates: synthesis, structure and ligand-sensitized photoluminescence. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 2010 (24), 3823–3828. 10.1002/ejic.201000535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurugan A.; Tan J.-C.; Cheetham A. K. Heterometallic inorganic-organic frameworks of sodium-bismuth benzenedicarboxylates. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10 (4), 1736–1741. 10.1021/cg901402f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L.; Xu Y.; Li X.; Wang Z.; Sun T.; Zhang X. Eu(3+)/Tb(3+) functionalized Bi-based metal-organic frameworks toward tunable white-light emission and fluorescence sensing applications. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47 (46), 16696–16703. 10.1039/C8DT03474E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziar J. C.; Cowan D. O. Photochemical heavy-atom effects. Acc. Chem. Res. 1978, 11 (9), 334–341. 10.1021/ar50129a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J. C.; Shen N. N.; Lin Y. P.; Gong L. K.; Tong H. Y.; Du K. Z.; Huang X. Y. Modulation of the structure and photoluminescence of bismuth(III) chloride hybrids by altering the ionic-liquid cations. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59 (18), 13465–13472. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c01883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.-C.; Lin Y.-P.; Chen D.-Y.; Lin B.-Y.; Zhuang T.-H.; Ma W.; Gong L.-K.; Du K.-Z.; Jiang J.; Huang X.-Y. X-ray scintillation and photoluminescence of isomorphic ionic bismuth halides with [Amim]+ or [Ammim]+ cations. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8 (20), 4474–4481. 10.1039/D1QI00803J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.-C.; Lin Y.-P.; Wu Y.-H.; Gong L.-K.; Shen N.-N.; Song Y.; Ma W.; Zhang Z.-Z.; Du K.-Z.; Huang X.-Y. Long lifetime phosphorescence and X-ray scintillation of chlorobismuthate hybrids incorporating ionic liquid cations. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9 (5), 1814–1821. 10.1039/D0TC05736C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anjaneyulu O.; Kumara Swamy K. C. Studies on bismuth carboxylates—synthesis and characterization of a new structural form of bismuth(III) dipicolinate. J. Chem. Sci. 2011, 123, 131–137. 10.1007/s12039-011-0108-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurugan A.; Li W.; Cheetham A. K. Bismuth 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylates: assembly of molecular units into coordination polymers, CO2 sorption and photoluminescence. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 4126–4134. 10.1039/c2dt12330d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakimi M.; Motieiyan E.; Bertolotti F.; Marabello D.; Nunes Rodrigues V. H. Three new bismuth(III) pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylate compounds: synthesis, characterization and crystal structures. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1099, 523–533. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2015.06.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stavila V.; Bulimestru I.; Gulea A.; Colson A. C.; Whitmire K. H. Hexaaquacobalt(II) and hexaaquanickel(II) bis(μ-pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylato)bis[(pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylato)bismuthate(III)] dihydrate. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2011, 67 (3), m65–m68. 10.1107/S0108270110053497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwitz A. C.; Nicholas A. D.; Breuer L. M.; Bertke J. A.; Knope K. E. Harnessing bismuth coordination chemistry to achieve bright, long-lived organic phosphorescence. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 16840–16851. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c02748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwitz A. C.; Nicholas A. D.; Magar R. T.; Dutta A. K.; Swanson J.; Hartman T.; Bertke J. A.; Rack J. J.; Jacobsohn L. G.; Knope K. E. Back in bismuth: controlling triplet energy transfer, phosphorescence, and radioluminescence via supramolecular interactions. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11 (42), 14848–14864. 10.1039/D3TC02040A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caracelli I.; Haiduc I.; Zukerman-Schpector J.; Tiekink E. R. T. Delocalised antimony(lone pair)- and bismuth-(lone pair)...π(arene) interactions: supramolecular assembly and other considerations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257 (21–22), 2863–2879. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arancibia J. A.; Escandar G. M. Room-temperature excitation-emission phosphorescence matrices and second-order multivariate calibration for the simultaneous determination of pyrene and benzo[a]pyrene. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 584 (2), 287–294. 10.1016/j.aca.2006.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikov G.; Shtykov S.; Goryacheva I. Sensitized room temperature phosphorescence of pyrene in sodium dodecylsulfate micelles with triphaflavine as energy donor. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 439 (1), 81–86. 10.1016/S0003-2670(01)01025-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikov G. V.; Shtykov S. N.; Shtykova L. S.; Goryacheva I. Y. Pyrene sensitized phosphorescence enhanced by the heavey atom effect in the water-heptane-sodium dodecyl sulfate-pentanol microemulsion. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2000, 49 (9), 1518–1521. 10.1007/bf02495152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan Raj A.; Sharma G.; Prabhakar R.; Ramamurthy V. Room-temperature phosphorescence from encapsulated pyrene induced by xenon. J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123 (42), 9123–9131. 10.1021/acs.jpca.9b08354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skryshevski Y. A.; Vakhnin A. Y. Excitation of phosphorescence of pyrene implanted into a photoconductive polymer. Phys. Solid 2007, 49 (5), 887–893. 10.1134/S1063783407050149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yansheng W.; Weijun J.; Changsong L.; Huiping Z.; Hongbo T.; Naichang Z. Study on micelle stabilized room temperature phosphorescence behaviour of pyrene by laser induced time resolved technique. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 1997, 53 (9), 1405–1410. 10.1016/S0584-8539(97)00043-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omary M. A.; Kassab R. M.; Haneline M. R.; Elbjeirami O.; Gabbaï F. P. Enhancement of the phosphorescence of organic luminophores upon interaction with a mercury trifunctional Lewis acid. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42 (7), 2176–2178. 10.1021/ic034066h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omary M. A.; Elbjeirami O.; Gamage C. S. P.; Sherman K. M.; Dias H. V. R. Sensitization of naphthalene monomer phosphorescence in a sandwich adduct with an electron-poor trinuclear silver(I) pyrazolate complex. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48 (5), 1784–1786. 10.1021/ic8021326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haneline M. R.; Tsunoda M.; Gabbaï F. P. π-Complexation of biphenyl, naphthalene, and triphenylene to trimeric perfluoro-ortho-phenylene mercury. Formation of extended binary stacks with unusual luminescent properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124 (14), 3737–3742. 10.1021/ja0166794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L.; Koehler K.; Jacobsohn L. G. Luminescence of undoped and Ce-doped hexagonal BiPO4. J. Lumin. 2020, 228, 117626. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2020.117626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M.; Koshimizu M.; Fujimoto Y.; Yanagida T.; Ono S.; Asai K. Luminescence and scintillation properties of Cs3BiCl6 crystals. Opt. Mater. 2016, 61, 115–118. 10.1016/j.optmat.2016.05.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W.; Niu X.; Wu X.; Ren Y.; Zhang Y.; Li G.; Su H.; Lei Y.; Xiao J.; Shi J.; et al. Halogen bonding: a new platform for achieving multi-stimuli-responsive persistent phosphorescence. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202200236 10.1002/anie.202200236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Shi H.; Ma H.; Ye W.; Song L.; Zan J.; Yao X.; Ou X.; Yang G.; Zhao Z.; et al. Organic phosphors with bright triplet excitons for efficient X-ray-excited luminescence. Nat. Photonics 2021, 15, 187–192. 10.1038/s41566-020-00744-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M.; Zhou P.; Li Z.; Liu J.; Yang Y.; Han K. New insights into the sensing mechanism of a phosphonate pyrene chemosensor for TNT. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20 (29), 19539–19545. 10.1039/C8CP01749B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou L.; Zhou Y.; Wu B.; Zhu L. The unusual physicochemical properties of azulene and azulene-based compounds. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30 (11), 1903–1907. 10.1016/j.cclet.2019.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beer M.; Longuet-Higgins H. C. Anomalous light emission of azulene. J. Chem. Phys. 1955, 23 (8), 1390–1391. 10.1063/1.1742314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasha M. Characterization of electronic transitions in complex molecules. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1950, 9 (0), 14–19. 10.1039/df9500900014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C.; Zhang S.; Gao Y.; Liu H.; Shan T.; Liang X.; Yang B.; Ma Y. Ternary emission of fluorescence and dual phosphorescence at room temperature: a single-molecule white light emitter based on pure organic aza-aromatic material. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28 (32), 1802407. 10.1002/adfm.201802407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Aslan K.; Previte M. J. R.; Geddes C. D. Metal-enhanced S2 fluorescence from azulene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 432 (4–6), 528–532. 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAINT Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- APEX3 Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SADABS ; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hubschle C. B.; Sheldrick G. M.; Dittrich B. ShelXle: a Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44 (6), 1281–1284. 10.1107/S0021889811043202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A 2008, 64 (1), 112–122. 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.