Abstract

Live, attenuated immunodeficiency virus vaccines, such as nef deletion mutants, are the most effective vaccines tested in the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) macaque model. In two independent studies designed to determine the breadth of protection induced by live, attenuated SIV vaccines, we noticed that three of the vaccinated macaques developed higher set point viral load levels than unvaccinated control monkeys. Two of these vaccinated monkeys developed AIDS, while the control monkeys infected in parallel remained asymptomatic. Concomitant with an increase in viral load, a recombinant of the vaccine virus and the challenge virus could be detected. Therefore, the emergence of more-virulent recombinants of live, attenuated immunodeficiency viruses and less-aggressive wild-type viruses seems to be an additional risk of live, attenuated immunodeficiency virus vaccines.

Despite extensive efforts, no safe and effective vaccine has been developed for the prophylaxis of AIDS. In the most commonly used animal model, the infection of monkey species with simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIV), live, attenuated immunodeficiency viruses are the most effective vaccines tested so far. Infection of macaques with an SIV harboring a deletion of the accessory gene nef leads to an asymptomatic course of infection in most infected monkeys (16, 32). The majority of monkeys vaccinated with such nef deletion mutants of SIV can efficiently control replication of pathogenic challenge virus strains (reviewed in references 1, 6, and 13) even in the absence of a sterilizing immunity (25). However, safety still is the predominant concern for the use of live, attenuated immunodeficiency virus vaccines in humans. Some monkeys infected with such attenuated viruses developed AIDS-like symptoms (2, 3). Since the efficacy of vaccination seems to depend on the replication capacity of the vaccine virus (20, 31), further attenuation of the vaccine virus might be limited. We therefore attempted to increase the immunogenicity of the vaccine virus by expressing the interleukin-2 (IL-2) gene from the vaccine virus (10, 11). When monkeys immunized with the altered vaccine virus were challenged, we noticed higher set point viral load levels in one of the vaccinated macaques than in unvaccinated control monkeys infected in parallel. Similarly, increased viral load levels and faster progression to AIDS after challenge were observed in two vaccinated monkeys from a second independent study (19). Therefore, we investigated whether a recombination event between the vaccine virus and the challenge virus could explain the negative effect of vaccination with live, attenuated immunodeficiency viruses in a subset of monkeys that were not protected from challenge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Infection of rhesus monkeys.

A challenge virus stock of the molecular clone KB9 of the SIV–human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) hybrid virus SHIV89.6P (SHIV) was prepared by transfection of ligated 50(R) and KB9 plasmids (15) in CEMx174 cells and subsequent propagation on rhesus monkey peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (27). The median (50%) tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of the virus stock was determined on C8166 cells (14). Positive cultures were identified by immunoperoxidase staining with serum of an SIV-infected macaque, as described previously (11). Monkeys 7742-IL2, 7744-IL2, 7755ΔNU, 7756ΔNU, 8489SHIV, and 8490SHIV were housed at the German Primate Center in Göttingen, Germany. Infection of 7742-IL2, 7744-IL2, 7755ΔNU, and 7756ΔNU with the vaccine virus and the first challenge with SIV have been previously described (11). They were rechallenged intravenously with 1,000 TCID50 of SHIV89.6-KB9. 8489SHIV and 8490SHIV, two rhesus monkeys of Indian origin (seronegative for SIV, D-type retroviruses, and simian T-cell leukemia virus type 1), were intravenously infected with SHIV at the same time with the same dose. The minimal number of PBMCs of infected macaques required for virus isolation in cocultures with C8166 was determined as a measure of cell-associated viral load (12). Infection of monkeys 343, 344, 348, 354, 356, 1060, and 1128 has been described previously (19).

PCR.

To characterize isolates recovered at different time points after infection from monkeys housed at the German Primate Center, C8166 cells were infected with the different isolates, lysed in buffer K (50 mM KCl, 15 mM Tris, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Tween 20, 100 μg of proteinase K per ml) shortly after peak syncytium formation, and subjected to PCR. Using the primers Sns (5′-GGATTAGACAAGGGCTTGAGCTCAC-3′) and Sna (5′-GTCCCTGCTGTTTCAGCGAGTTCCC-3′), which flank the deletions in nef and the U3 region, fragments were amplified from the lysates. The PCR products were size separated by agarose gel electrophoresis side by side with the PCR products derived from plasmids containing full-length nef or SIVΔNU sequences to discriminate between SIV-IL2, nef deletion mutants of SIV, and SIV. To determine the presence of HIV-1 env, a second PCR was performed with the HIV-1-specific primers Hes (5′-GTGGGTCCACAGTCTATTATGGGGTA-3′) and Hea (5′-CCTCATGCATCTGATCTACCATGT-3′). A third PCR with the primers Ses (5′-TACTCCAGAGGCTCTCTGCGA-3′) and Δna (5′-GGTATCTAACATATGCCTCATAAGT-3′) was used to detect SIV env and nef sequences present on the same template. To characterize isolates from monkeys 343, 344, 348, 354, 356, 1060, and 1128 by PCR, genomic DNA was prepared from infected human peripheral blood lymphocytes with DNA-Stat-60 solution (Tel Test B Inc., Friendswood, Tex.). The length of the nef gene was determined by PCR with the primers Sns and Sna as described above. To analyze whether SIV env and nef sequences were present on the same template the primers Ses and Δn2a (5′-GGCCTCACTGATACCCCTACCAAGT-3′) were used. To detect the SHIV challenge virus the primers He2s (5′-GGATTGTGGAACTTCTGGGACGCA-3′) and Δn2a were used for the PCR. The following conditions were used for all PCRs: 94°C for 2 min, followed by 39 cycles of 40 s at 94°C, 1 min at 61°C, and 1 min at 72°C. After each cycle, the extension time was prolonged by 1 s. For sequence analyses, PCR products were gel purified and sequenced with dye-labeled dideoxy nucleotides on an automated 373A or 310 sequencer (Applied Biosystems) according to protocols provided by the manufacturer.

Immunological methods.

PBMCs were phenotypically characterized by three-color fluorescence analysis on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). For determination of lymphocyte subsets, a gate was set on forward and side light scatter to include T cells, B cells, and NK cells, with a minimum of contaminating macrophages. These cell populations were defined by monoclonal antibodies against CD3 (FN18, provided by M. Jonkers, Biomedical Primate Research Center, Rijswijk, The Netherlands), CD20 (H299; Coulter, Krefeld, Germany), CD16 and CD56 (3G8 and B159; Immunotech, Hamburg, Germany), and CD14 (RM052; Immunotech). CD4+ T cells (OKT4; Ortho, Neckargemuend, Germany) were further differentiated into naive and memory T-helper cells according to low- or high-level expression of CD29 (4B4; Coulter).

RESULTS

In one study designed to increase the immunogenicity of live, attenuated SIV vaccines, four rhesus monkeys were infected with a nef deletion mutant of SIV expressing interleukin-2 (SIV-IL2) or the parental nef deletion mutant, SIVΔNU (10). When these monkeys were challenged with pathogenic SIVmac239, no challenge virus could be isolated, although high viral loads were observed in two naive control animals infected in parallel (11). Using a nested PCR approach, challenge virus sequences could be detected sporadically in the PBMCs or lymph nodes of three of the four vaccinated macaques 6 or 37 weeks postchallenge (11). To further investigate the effect of IL-2 on vaccine protection, these monkeys were rechallenged with 1,000 TCID50 of SHIV (15) 37 weeks after the first challenge.

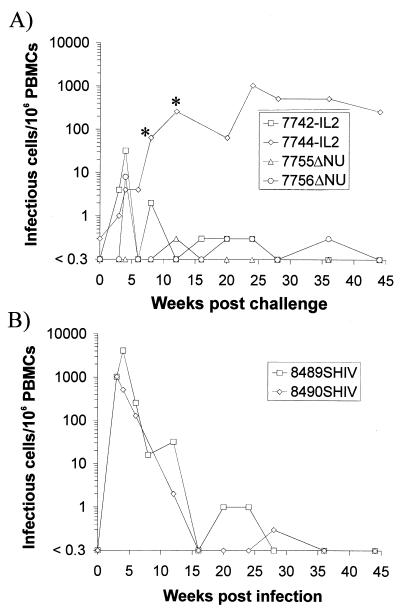

At the time of the second challenge, virus could only be isolated from monkey 7744-IL2 (Fig. 1A). After challenge with SHIV, an increase in the cell-associated viral load was observed in all vaccinated macaques with the exception of 7755ΔNU (Fig. 1A). However, the peak cell-associated viral load during the first months after challenge was approximately 100-fold lower in the vaccinated macaques than that in two naive control monkeys infected in parallel (Fig. 1). One monkey, 7744-IL2, developed a high cell-associated viral load 2 to 6 months after challenge with SHIV, which exceeded the levels seen during this interval in the two naive control monkeys (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Cell-associated viral load after inoculation of SIV-IL2- and SIVΔNU-infected rhesus monkeys (A) or naive rhesus monkeys (B) with SHIV. The numbers of infectious cells per 106 PBMCs were calculated from the minimal number of PBMCs required for virus isolation in coculture with C8166 cells. The four-digit numbers are monkey designations and each is followed by an abbreviation indicating the virus with which the monkey was first infected, as follows: IL2, SIV-IL2; ΔNU, SIVΔNU; and SHIV, molecular clone KB9 of SHIV89.6P. ∗, end point of the limiting dilution coculture not reached at this time point.

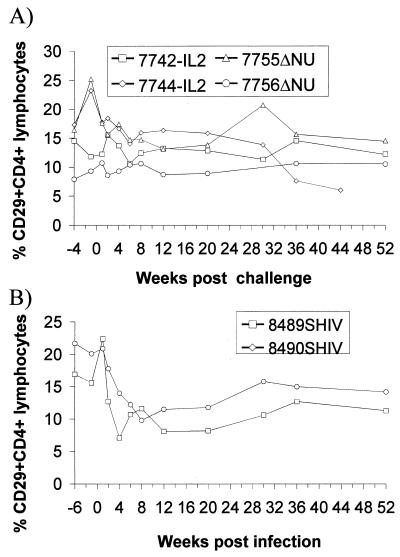

To assess the clinical consequences of the SHIV challenge, the percentage of CD29+ CD4+ lymphocytes was determined, since a drop in this population is an early prognostic marker for a decline in immune function in humans (4, 8) and macaques (17, 22). A transient decline in the percentage of CD29+ CD4+ cells was observed in SHIV-infected control monkeys during the acute phase of infection but not in the vaccinated macaques (Fig. 2). A reduced percentage of CD29+ CD4+ cells was also seen in 7744-IL2 36 and 42 weeks postchallenge, which is consistent with the high viral load in this monkey. All animals remained asymptomatic, with the exception of 7744-IL2, which developed a splenomegaly and generalized, progressing lymphadenopathy by 16 weeks following SHIV challenge.

FIG. 2.

Percentage of CD29+ CD4+ cells in peripheral blood lymphocytes of SIV-IL2- and SIVΔNU-infected rhesus monkeys (A) or naive rhesus monkeys (B) after exposure to SHIV. The numbers of CD29+ CD4+ cells are expressed as percentages of total lymphocytes. The designations for the monkeys are as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

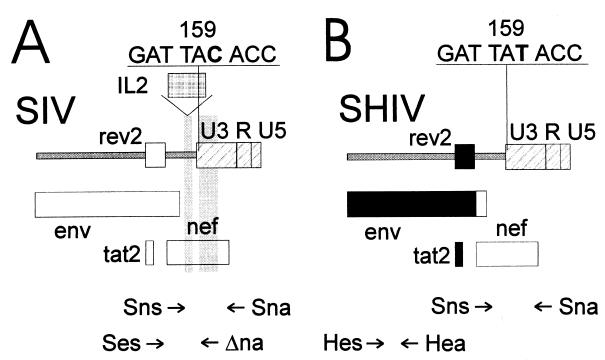

To analyze whether the increase in the cell-associated viral load in the vaccinated macaques after challenge was due to challenge virus infection or reactivation of the vaccine virus, isolates recovered after challenge were characterized by PCR. One primer pair (Sns plus Sna) spanning the IL-2 gene insertion site was used to discriminate the vaccine virus from the challenge viruses (Fig. 3A). A second primer pair specific for HIV-1 env (Hes plus Hea) was used to identify the SHIV challenge virus (Fig. 3B). At the time of challenge, virus had been isolated only from monkey 7744-IL2. Characterization of this isolate by PCR with primers flanking the inserted IL-2 gene revealed the presence of the SIV-IL2 vaccine virus (Tables 1 and 2). As previously observed (10), the isolated SIV-IL2 virus contained large deletions in the IL-2 gene. Of note, all nine isolates recovered from this animal between the first and the second challenge contained vaccine virus and not the first challenge virus (11). Isolates recovered from 7742-IL2 and 7756ΔNU after SHIV challenge contained SHIV (Table 2), as indicated by the presence of full-length nef and HIV-1 env sequences. SHIV could also be detected in the isolate recovered 3 weeks after challenge of 7744-IL2. Thereafter, the HIV-1 env gene could not be detected in the isolates of this monkey (Table 2), although the cell-associated viral load was high. Since the sensitivity of the HIV-1 env-specific PCR was 10-fold higher than the sensitivity of the PCR detecting the full-length nef gene (data not shown), the SHIV challenge virus did not seem to contribute significantly to the high viral loads observed. With the use of one primer specific for the SIV env region deleted in SHIV (Ses) and a second primer specific for the nef region deleted in SIV-IL2 (Δna), a colocalization of SIV env and nef sequences on the same template could be detected in monkey 7744-IL2 starting 8 weeks postchallenge (Table 2). To exclude the possibility that this result was due to an overlap extension PCR artifact, genomic DNA of cells infected with the vaccine viruses was mixed with genomic DNA of cells infected with the SIVmac239 or the SHIV challenge virus. A PCR product of the right size was obtained whenever the genomic DNA of SIVmac239-infected cells was present in the mixture but never when the genomic DNA of SHIV-infected cells was mixed with the genomic DNA of cells infected with the vaccine viruses (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Characterization of isolates recovered from vaccinated macaques after SHIV challenge. The locations of the primers used for the identification of SIV vaccine (SIV-ΔNU and SIV-IL2) and wild-type viruses (A) and the SHIV challenge virus (B) are shown. The shaded regions mark deletions in the vaccine virus, and the regions marked in black are derived from HIV-1. The nucleotide sequences of codons 158 to 160 of the nef genes of wild-type SIV and of SHIV are given above the map.

TABLE 1.

Expected sizes of PCR products recovered from vaccinated macaques after SHIV challengea

| Primer pair | Expected size (bp) of product

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIV-wt | SIV-ΔNU | SIV-IL2 | SHIV | |

| Sns plus Sna | 672 | 163 | 637 | 672 |

| Hes plus Hea | neg. | neg. | neg. | 218 |

| Ses plus Δna | 760 | neg. | neg. | neg. |

neg., negative; SIV-wt, wild-type SIV.

TABLE 2.

Summary of PCR characterization of the isolates challenged with SHIV

| Monkey | Virus recovereda after the following no. of weeks postchallenge:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 | |

| 7742-IL2 | C | C | C | C | V/C | C | |||

| 7744-IL2 | V | V/C | V | V | V/Sb | Sb | S | Sb | S |

| 7755ΔNU | V | ||||||||

| 7756ΔNU | C | C | C | C | |||||

V, vaccine virus (results with various primer pairs were as follows: Sna plus Sna, truncated product; Hes plus Hea, negative; and Ses plus Δna, negative); C, SHIV challenge virus (results with various primer pairs were as follows: Sns plus Sna, positive; Hes plus Hea, positive; and Ses plus Δna, negative); S, wild-type SIV (results with various primer pairs were as follows: Sns plus Sna, positive; Hes plus Hea, negative; and Hes plus Δna, positive); V/C, SHIV challenge virus and vaccine virus (results with various primer pairs were as follows: Sns plus Sna, positive plus truncated; Hes plus Hea, positive; and Ses plus Δna, negative); V/S, vaccine virus and wild-type SIV (results with various primer pairs were as follows: Sns plus Sna, positive and truncated; Hes plus Hea, negative; and Ses plus Δna, positive).

Sample was sequenced.

The presence of wild-type SIV could be due to outgrowth of the first SIV challenge virus. Wild-type nef sequences had been detected in a lymph node of 7744-IL2 at the time of the SHIV challenge in one out of two independent nested PCRs (11). However, it could not be detected by nested PCR from PBMCs and wild-type SIV was never isolated prior to the second challenge (11). Alternatively, the vaccine virus and the SHIV challenge virus could recombine with wild-type SIV. Since both viruses, the vaccine virus and the SHIV challenge virus, were present at the same time at levels high enough for virus isolation, recombination seemed to be possible. To discriminate between these two possibilities, the nef genes of isolates recovered from 7744-IL2 after SHIV challenge were sequenced. The molecular SHIV clone used for challenge contains a silent point mutation from TAC to TAT at codon 159 of SIVmac239 Nef in a region that is deleted in SIV-IL2. Sequencing of the nef gene of an SHIV isolate recovered 4 weeks after SHIV infection from the naive control monkey 8489SHIV confirmed the presence of this mutation in SHIV. In contrast, the nef genes of isolates recovered from monkeys 8143SIV and 8148SIV, which were infected with SIVmac239 in parallel to 7744-IL2 (11), contained the TAC codon at position 159. Sequence analyses further revealed the presence of the TAT codon characteristic for SHIV in isolates recovered from 7744-IL2 8, 12, and 20 weeks post-SHIV challenge. Since no HIV-1 env sequences were present at the same time (Table 2), this suggests that nef sequences of SHIV recombined with the vaccine virus to form a virus like SIV. However, reactivation of the SIV challenge virus and subsequent mutation at codon 159 from TAC to TAT cannot be formally excluded.

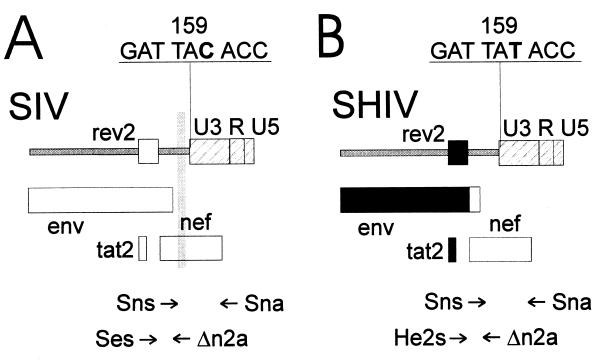

In a separate study (19), in which rhesus monkeys had been vaccinated with a nef deletion mutant of SIV (16) prior to challenge with the virus isolate SHIV89.6PD (24), viral load curves strikingly similar to the viral load curve in monkey 7744-IL2 were observed. While naive control monkeys developed high viral loads during primary SHIV infection, they were able to maintain low viral load levels at later time points. Two of five vaccinated macaques (354 and 356 in reference 19) had reduced viral load levels after SHIV challenge but developed a higher viral load than naive control monkeys 6 to 8 weeks postchallenge. Isolates from monkeys 354 and 356 obtained before and after the SHIV challenge were characterized by three separate PCRs. One primer located in the nef region deleted in the vaccine virus (Δn2a) was combined with one primer specific for SIV env (Ses) or HIV-1 env (He2s) (Fig. 4A and B; Table 3). PCR analyses with SIVmac239 or SHIV89.6 plasmid DNA confirmed the specificity of the SIV env and HIV-1 env primer (data not shown). A third PCR with primers flanking the nef deletion (Sns plus Sna) was used to determine the status of the nef gene. In monkey 354 and in the naive control monkeys, 1060 and 1128, the SHIV challenge virus could be detected in the virus isolates 1 week after inoculation as indicated by the presence of a full-length nef gene and HIV-1 env sequences (Table 4). PCR analyses with primers Ses and Δn2a revealed that all isolates recovered 2 weeks after challenge or at later time points from 354 contained a virus in which sequences deleted in SIVΔnef were present on the same template as SIV env sequences. The positive PCR results obtained with this primer pair were not due to an overlap extension PCR artifact, since mixing of genomic DNA of cells infected with the vaccine virus with genomic DNA of cells infected with the challenge virus did not lead to a positive PCR signal. Since monkey 354 had never been exposed to wild-type SIV, this indicates recombination of SIVΔnef with SHIV89.6PD. In addition to the recombinant SIV, the SHIV challenge virus remained also detectable in monkey 354 at most time points. In monkey 356, the recombinant SIV was first detected 8 weeks postchallenge and at all time points analyzed thereafter. Of note, the initial detection of the recombinant SIV precisely coincides with the reported increase in viral load after challenge in these two monkeys (19). Using a nested PCR approach, the recombinant SIV could also be detected in the genomic DNA of PBMCs of monkeys 354 and 356 at the time of autopsy (data not shown). In three SIVΔnef-infected monkeys (343, 344, and 348 in reference 19), which maintained low viral load levels after SHIV challenge, the recombinant SIV could not be detected during the first 4 months after challenge (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Characterization of isolates recovered from vaccinated macaques after SHIV89.6PD challenge. The location of the primers used for the identification of SIV vaccine (SIVΔnef) and wild-type viruses (A) and the SHIV challenge virus (B) are shown. The shaded regions mark deletions in the vaccine virus, and the regions marked in black are derived from HIV-1. The nucleotide sequences of codons 158 to 160 of the nef genes of SIVΔnef and of SHIV are given above the map.

TABLE 3.

Expected sizes of PCR products recovered from vaccinated macaques after SHIV89.6PD challengea

| Primer pair | Expected size (bp) of product

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| SIV-wt | SIV-Δnef | SHIV | |

| Sns plus Sna | 672 | 490 | 672 |

| He2s plus Δn2a | neg. | neg. | 422 |

| Ses plus Δn2a | 383 | neg. | neg. |

neg., negative; SIV-wt, wild-type SIV.

TABLE 4.

Summary of the PCR characterization of the isolates challenged with SHIV89.6PD

| Monkey | Virus recovereda after the following no. of weeks postchallenge:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 17 | 20 | Unspecifiedc | |

| H354 | V | C | C/S | C/S | C/S | C/Sb | C/S | C/Sb | S |

| H356 | V | V | V | V | V | Sb | S | Sb | C/Sb |

| RQ1060 | n | Cb | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| RQ1128 | n | Cb | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

Recovered viruses were as follows (with results of PCR with various primers shown in parentheses): V, vaccine virus (Sns plus Sna, truncated; He2s plus Δn2a, negative; and Ses plus Δn2a, negative); C, SHIV challenge virus (Sns plus Sna, positive; He2s plus Δn2a, positive; and Ses plus Δ2na, negative); S, wild-type SIV (Sns plus Sna, positive; He2s plus Δn2a, negative; and Ses plus Δ2na, positive); C/S, challenge virus and wild-type SIV (Sns plus Sna, positive; He2s plus Δn2a, positive; and Ses plus Δ2na, positive). n, not analyzed.

Sample was sequenced.

These viruses were recovered at death.

To sequence the nef genes of the recombinant SIV, the nef gene was amplified from the virus isolates with one primer specific for SIV env (Ses) and one primer located at the 3′ end of nef (Δna). Sequence analysis of the PCR products revealed a nef open reading frame for the entire region analyzed (codon 1 to 210) and the presence of the TAT codon at position 159 in two independent isolates analyzed from monkey 354 and in three isolates analyzed from monkey 356. Sequence analyses of the SHIV challenge virus recovered 1 week after infection of the naive control monkeys (1060 and 1128) confirmed the presence of the TAT codon at position 159 in SHIV89.6PD. Since the vaccine strain, like all other SIVmac strains, has the TAC codon at this position, the nef gene of the recombinant SIV must have been derived from SHIV-89.6PD.

DISCUSSION

As observed in previous studies, live, attenuated SIV vaccines can provide protection against challenge viruses containing highly divergent env genes (5, 9, 21, 23, 25, 30). The degree of protection seems to depend on the replication capacity of the vaccine strain (20, 31). Most likely, the virulence of the challenge virus also affects the degree of protection. In our experiment, the vaccine strain replicated at high titers during the acute phase of infection and conferred protection against productive infection with SIVmac239 (10, 11). When these protected monkeys were rechallenged with an SIV–HIV-1 hybrid virus that had been passaged to increase its virulence (15), SHIV virus could be isolated from three of the four exposed monkeys. Although the viral load was reduced in comparison to that observed for unvaccinated control monkeys, protection seemed to be less efficient against SHIV than against the homologous SIVmac239.

In monkey 7744-IL2, which had the highest viral load prior to SHIV challenge, both the vaccine virus and the SHIV challenge virus were present at detectable levels early after challenge. Concomitant with an increase in viral load to levels far exceeding the viral load observed in SHIV-infected control monkeys at the same time after exposure, a nef-containing SIVmac239 virus emerged. Since wild-type nef sequences had been detected in a lymph node of 7744-IL2 at the time of the SHIV challenge in one out of two independent nested PCRs (11), this could be due to reactivation of the first SIVmac239 challenge virus. However, the viral load of the first SIVmac239 challenge virus was extremely low up to the time of the second challenge, since it was never detected by nested PCR in the PBMCs of this animal and since it was never possible to isolate the SIVmac239 challenge virus prior to the second challenge (11). Sequence analyses further revealed the presence of a silent point mutation at codon 159 of nef of the emerging SIVmac239.

This mutation was present in the SHIV challenge virus used in this study as a result of passaging SHIV89.6 in monkeys to increase its virulence. This mutation was not found in the SIVmac239 challenge virus used in this study, and codon 159 is conserved among all SIVmac sequences compiled in the Los Alamos sequence database (18). Taken together, the simultaneous presence of the vaccine strain and the SHIV challenge virus after SHIV challenge, the low viral load level of the first SIVmac239 challenge virus prior to the second challenge, and the detection of the SHIV-specific mutation in the nef gene of the emerging SIVmac239 at a codon that is conserved among all SIVmac239 isolates provide evidence for recombination of the vaccine strain and the SHIV challenge virus. However, reactivation of the SIV challenge virus and subsequent mutation of the codon at position 159 from TAC to TAT cannot be formally excluded in this monkey.

Therefore, our analyses were extended to a second study, in which monkeys had been vaccinated with a different nef deletion mutant prior to challenge with the SHIV89.6PD isolate. In contrast to the first study, the monkeys had not been exposed to wild-type SIV. Concomitant with an increase in viral load, a recombinant of the vaccine virus and the challenge virus appeared in those two vaccinated monkeys, which had the highest viral load prior to challenge and which developed higher set point RNA levels after challenge than the two naive control monkeys infected in parallel. Again, the nef gene of the recombinants contained the TAT codon at position 159 that is characteristic of SHIV. Since both the vaccine virus and the SHIV challenge virus persist at lower levels than SIVmac239, the recombinant seems to have a selective advantage leading to its outgrowth.

Since monkey 7744-IL2 was previously protected from productive SIVmac239 infection, although SIVmac239 challenge virus sequences had been detected at one time point by nested PCR (11), the question of why the potential recombinant cannot be controlled arises. A similar situation was observed previously in monkeys infected with the attenuated SIVmacC8, which contains a 12-bp deletion in nef. Although SIVmacC8-infected monkeys were protected from challenges with pathogenic viruses, they developed disease after repair of the deletion in nef (7, 26, 28). One explanation could be that the compartment the pathogenic exogenous virus reaches is better controlled by the immune system and differs from the compartment recombinants emerge from. Alternatively, since the vaccine virus has already adapted to low-level persistence, restoration of nef function might suddenly expose the host organism to a pathogenic virus that has already escaped control by the immune system. The latter might be particular troublesome if live, attenuated HIV vaccines are to be used in humans. Although humans are usually exposed to pathogenic viruses, recombinants between a host-adapted vaccine strain and a pathogenic virus might lead to more rapid progression to disease. In addition, the emergence of new variants might be favored. However, it remains to be determined if recombination is a problem when virus strains attenuated to a greater degree are used for vaccination.

For recombination to occur, one cell has to be coinfected by two viruses. The frequency of this event in an infected host is unknown. Further variables include the efficiency of the recombination event, the viral load of both viruses, and the level of resistance to superinfection. Therefore it was not surprising that the recombination event was observed in those monkeys which had the highest viral load levels prior to challenge. Recombination of two attenuated SIV strains has been previously observed in one monkey simultaneously infected with a nef deletion mutant and a vpr-vpx double deletion mutant of SIVmac239 (29). The viral load level at which recombination occurred could not be assessed in this experiment; however, the peak viral load that is usually induced by nef deletion mutants of SIVmac239 (10, 31) is approximately 100-fold higher than the viral load we observed in the blood of the vaccinated monkeys after SHIV challenge but prior to the emergence of recombinants. Therefore, the observation that two virus strains can recombine at moderate viral load levels further suggests that recombination is a frequently occurring process in natural immunodeficiency virus infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (SIV collaborative research project, 01 KI 9478/8 and 01 KI 9763/8) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 466, Teilprojekt B4). M.G.L. obtained support from a Cooperative Agreement (DAMD17-93-V 3004) between the U.S. Army Medical Research Command and the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine. J.S. was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the G. Harold and Leila Mathew Foundation, the Friends 10, the late William McCarthy-Cooper, and Douglas and Judith Krupp.

We thank M. Wirth, K. Bräutigam, J. Greenhouse, and U. Sauer for excellent technical assistance, F. Kirchhoff for helpful discussion, and G. Hunsmann and B. Fleckenstein for continuous support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almond N M, Heeney J L. AIDS vaccine development in primate models. AIDS. 1998;12(Suppl. A):S133–S140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba T W, Jeong Y S, Pennick D, Bronson R, Greene M F, Ruprecht R M. Pathogenicity of live, attenuated SIV after mucosal infection of neonatal macaques. Science. 1995;267:1820–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.7892606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba T W, Liska V, Khimani A H, Ray N B, Dailey P J, Penninck D, Bronson R, Greene M F, McClure H M, Martin L N, Ruprecht R M. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nat Med. 1999;5:194–203. doi: 10.1038/5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blatt S P, McCarthy W F, Bucko Krasnicka B, Melcher G P, Boswell R N, Dolan J, Freeman T M, Rusnak J M, Hensley R E, Ward W W, Barnes D, Hendrix C W. Multivariate models for predicting progression to AIDS and survival in human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:837–844. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogers W M, Niphuis H, ten Haaft P, Laman J D, Koornstra W, Heeney J L. Protection from HIV-1 envelope-bearing chimeric simian immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) in rhesus macaques infected with attenuated SIV: consequences of challenge. AIDS. 1995;9:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desrosiers R C. Live attenuated vaccines: best hope to prevent HIV? HIV Adv Res Ther. 1996;3:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dittmer U, Nisslein T, Bodemer W, Petry H, Sauermann U, Stahl Hennig C, Hunsmann G. Cellular immune response of rhesus monkeys infected with a partially attenuated nef deletion mutant of the simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1995;212:392–397. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolan M J, Clerici M, Blatt S P, Hendrix C W, Melcher G P, Boswell R N, Freeman T M, Ward W, Hensley R, Shearer G M. In vitro T cell function, delayed-type hypersensitivity skin testing, and CD4+ T cell subset phenotyping independently predict survival time in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:79–87. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn C S, Hurtel B, Beyer C, Gloecker L, Ledger T N, Moog C, Kieny M P, Methali M, Schmitt D, Gut J P, Kirn A, Aubertin A M. Protection of SIVmac-infected macaque monkeys against superinfection by a simian immunodeficiency virus expressing envelope glycoproteins of HIV type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:913–922. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gundlach B R, Linhart H, Dittmer U, Sopper S, Reiprich S, Fuchs D, Fleckenstein B, Hunsmann G, Stahl-Hennig C, Überla K. Construction, replication, and immunogenic properties of a simian immunodeficiency virus expressing interleukin-2. J Virol. 1997;71:2225–2232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2225-2232.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gundlach B R, Reiprich S, Sopper S, Means R E, Dittmer U, Mätz-Rensing K, Stahl-Hennig C, Überla K. Env-independent protection induced by live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccines. J Virol. 1998;72:7846–7851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7846-7851.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoch J, Lang S M, Weeger M, Stahl-Hennig C, Coulibaly C, Dittmer U, Hunsmann G, Fuchs D, Müller J, Sopper S, Fleckenstein B, Überla K T. vpr deletion mutant of simian immunodeficiency virus induces AIDS in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1995;69:4807–4813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4807-4813.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson R P. Live attenuated AIDS vaccines: hazards and hopes. Nat Med. 1999;5:154–155. doi: 10.1038/5515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson V, Byington R E. Quantitative assays for virus infectivity. In: Aldovini A, Walker B D, editors. Techniques in HIV research. New York, N.Y: Stockton Press; 1990. pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karlsson G B, Halloran M, Li J, Park I-W, Gomila R, Reimann K A, Axthelm M K, Iliff S A, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Characterization of molecularly cloned simian-human immunodeficiency viruses causing rapid CD4+ lymphocyte decline in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1997;71:4218–4225. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4218-4225.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kestler H W, Ringler D J, Mori K, Panicali D L, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kneitz C, Kerkau T, Müller J, Coulibaly C, Stahl-Hennig C, Hunsmann G, Hünig T, Schimpl A. Early phenotypic and functional alterations in lymphocytes from simian immunodeficiency virus infected macaques. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;36:239–255. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(93)90022-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korber B, Hahn B, Foley B, Mellors J W, Leitner T, Myers G M F, Kuiken C L. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1997: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis M G, Yalley-Ogunro J, Greenhouse J J, Brennan T P, Jiang J B, VanCott T C, Lu Y, Eddy G A, Birx D L. Limited protection from a pathogenic chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency virus challenge following immunization with attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1999;73:1262–1270. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1262-1270.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lohman B L, McChesney M B, Miller C J, McGowan E, Joye S M, Van Rompay K K, Reay E, Antipa L, Pedersen N C, Marthas M L. A partially attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus induces host immunity that correlates with resistance to pathogenic virus challenge. J Virol. 1994;68:7021–7029. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7021-7029.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller C J, McChesney M B, Lü X, Dailey P J, Chutkowski C, Lu D, Brosio P, Roberts B, Lu Y. Rhesus macaques previously infected with simian/human immunodeficiency virus are protected from vaginal challenge with pathogenic SIVmac239. J Virol. 1997;71:1911–1921. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1911-1921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morphey-Corb M, Martin L N, Davison-Fairburn B, Montelaro R C, Miller M, West M, Ohkawa S, Baskin G, Zhang J-Y, Putney S D, Allison A C, Eppstein D A. A formalin-inactivated whole SIV vaccine confers protection in macaques. Science. 1989;246:1293–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.2555923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quesada-Rolander M, Mäkitalo B, Thorstensson R, Zhang Y-J, Castanos-Velez E, Biberfeld G, Putkonen P. Protection against mucosal SIVsm challenge in macaques infected with a chimeric SIV that expresses HIV type 1 envelope. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:993–999. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reimann K A, Li J, Veazey R, Halloran M, Park I-W, Karlsson G B, Sodroski J, Letvin N. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus isolate env causes AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:6922–6928. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6922-6928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shibata R, Siemon C, Czajak S C, Desrosiers R C, Martin M A. Live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccines elicit potent resistance against a challenge with a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 chimeric virus. J Virol. 1997;71:8141–8148. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8141-8148.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stahl-Hennig C, Dittmer U, Nisslein T, Pekrun K, Petry H, Jurkiewicz E, Fuchs D, Wachter H, Rud E, Hunsmann G. Attenuated SIV imparts immunity to challenge with pathogenic spleen-derived SIV but cannot prevent repair of nef deletion. Immunol Today. 1996;51:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Überla K, Stahl Hennig C, Böttiger D, Mätz-Rensing K, Kaup F J, Li J, Haseltine W A, Fleckenstein B, Hunsmann G, Öberg B, Sodroski J. Animal model for the therapy of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome with reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8210–8214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whatmore A M, Cook N, Hall G A, Sharpe S, Rud E W, Cranage M P. Repair and evolution of nef in vivo modulates simian immunodeficiency virus virulence. J Virol. 1995;69:5117–5123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5117-5123.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wooley D P, Smith R A, Czajak S, Desrosiers R C. Direct demonstration of retroviral recombination in a rhesus monkey. J Virol. 1997;71:9650–9653. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9650-9653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyand M S, Manson K, Montefiori D C, Lifson J D, Johnson R P, Desrosiers R C. Protection by live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus against heterologous challenge. J Virol. 1999;73:8356–8363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8356-8363.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyand M S, Manson K H, Garcia-Moll M, Montefiori D, Desrosiers R C. Vaccine protection by a triple deletion mutant of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1996;70:3724–3733. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3724-3733.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyand M S, Manson K H, Lackner A A, Desrosiers R C. Resistance of neonatal monkeys to live attenuated vaccine strains of simian immunodeficiency virus. Nat Med. 1997;3:32–36. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]