Abstract

Objectives

The increase in gabapentinoid prescribing is paralleling the increase in serious harms. To describe the low back pain workers compensation population whose management included a gabapentinoid between 2010 and 2017, and determine secular trends in, and factors associated with gabapentinoid use.

Methods

We analysed claim-level and service-level data from the Victorian workers’ compensation programme between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2017 for workers with an accepted claim for a low back pain injury and who had programme-funded gabapentinoid dispensing. Secular trends were calculated as a proportion of gabapentinoid dispensings per year. Poisson, negative binomial and Cox hazards models were used to examine changes over time in incidence and time to first dispensing.

Results

Of the 17 689 low back pain claimants, one in seven (14.7%) were dispensed at least one gabapentinoid during the first 2 years (n=2608). The proportion of workers who were dispensed a gabapentinoid significantly increased over time (7.9% in 2010 to 18.7% in 2017), despite a reduction in the number of claimants dispensed pain-related medicines. Gabapentinoid dispensing was significantly associated with an opioid analgesic or anti-depressant dispensing claim, but not claimant-level characteristics. The time to first gabapentinoid dispensing significantly decreased over time from 311.9 days (SD 200.7) in 2010 to 148.2 days (SD 183.1) in 2017.

Conclusions

The proportion of claimants dispensed a gabapentinoid more than doubled in the period 2010–2017; and the time to first dispensing halved during this period.

Keywords: Back Pain, Veterans, Health services research

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The increase in gabapentinoid prescribing is paralleling the increase in serious harms such as misuse, abuse and death, but it is unclear on gabapentinoid dispensing trends in people with worker’s compensation claims who have a primary issue of low back pain.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The proportion of workers dispensed a gabapentinoid significantly increased over time and the time to first dispensing shortened.

One in seven low back pain claimants were dispensed a gabapentinoid at least once during the first 2 years of their claim.

Gabapentinoid dispensing was significantly associated with an opioid analgesic or anti-depressant claim.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Although the proportion of analgesic medicines claimed by people with low back pain-related worker’s compensation claims decreased over time, gabapentinoid use increased.

Introduction

Low back pain is the leading cause of disability worldwide.1 Of the >500 million people estimated to experience back pain globally, the prevalence is greater in women than men and prevalence increases with age.1 Back pain is commonly experienced in the working age group,2 and survey data indicates that one in five workers with work-related low back pain seek workers’ compensation for their back injury, and claim filing is more frequent among workers in the 45–64 years age group.3 Data from Australian workers’ compensation programmes indicates that the median time off work is 9 weeks in those people with a primary compensation claim related to the low back.4

The management of low back pain commonly includes pharmacological management. Some clinical practice guidelines for managing low back pain now recommend avoiding some medicines, such as opioid analgesics and gabapentinoids (pregabalin, gabapentin),5 as the benefit often does not outweigh the harms. In people with work-related low back compensation claims,6 opioid analgesics have been found to lead to prolonged work disability with an increased daily dose,7 compared with other medicines like non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs8 and are associated with increased opioid-related deaths.9 The increasing incidence of gabapentinoid-related harms have been documented in the literature, such as abuse, misuse, dependence or overdose.10 11 However, the extent of gabapentinoid-related harms in work-related low back compensation claims is not well known.

Gabapentinoids are anti-epileptic drugs that are approved to treat a small number of neuropathic pain conditions, such as post-herpetic neuralgia.12 But in recent times, there has been a shift in increased ‘off-label’ prescribing (ie, for non-approved conditions) partially in response to clinicians seeking a non-opioid alternative following increased awareness of opioid harm.13 In Australia, low back pain is a key driver of off-label pregabalin prescribing,14 and there have been increases in gabapentinoid prescribing to patients with low back pain in primary care.15 The use of gabapentinoids for back pain can be associated with providing low-value care, that is, when the probable benefits do not exceed the potential harms.16 For example, pregabalin provides no greater pain relief than placebo in patients with sciatica (a severe form of back pain and leg pain) but with an increased rate of adverse events.17

Although gabapentinoid prescribing has increased in Australia14 15 and internationally18 19 over the last decade, it is unclear if similar prescribing trends have occurred in workers’ compensation populations. The extent to which gabapentinoids are prescribed in workers’ compensation cohort is infrequently reported. Analysis of North American jurisdiction (Louisiana) workers’ compensation claims revealed a doubling in gabapentin claims between 2008 and 2018, and an 80% decrease in pregabalin reimbursement claims during the same time. However, these trends are for a single geographical location of private insurance claims, and the extent these trends are associated with low back pain injuries is unknown.20 Understanding the secular prescribing trends in workers can give insight into whether workers’ compensation claimants receive gabapentinoids to manage their back pain. Therefore, this study aimed to examine gabapentinoid dispensing between 2010 and the end of 2019 in a low back pain workers’ compensation population. A second aim was to determine factors associated with gabapentinoid dispensing.

Methods

Database

This study analysed retrospective cohort data from the compensation database of the workers’ compensation regulator in the state of Victoria, Australia, the second most populous state. The Victorian workers’ compensation programme covers approximately 85% of 3.2 million Victorian workers in 2017. A standard claim is recorded in the database once 10 days have been lost from work, or a threshold of healthcare expenditure has been reached (~$A700 in the 2018/2019 financial year). The healthcare expenditure includes reimbursement to the payee for reasonable costs related to the work-related injury or illness.

Sample

Workers aged 15–80 years with accepted workers’ compensation time-loss claims for low back pain received by the insurer between the 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2017 were included. Time loss claims were those with at least 1 day of workers’ compensation-funded income replacement. Low back pain was defined using the database’s coding system, Vcode (online supplemental appendix 1). Claimant details included variables related to the claim (claim filing and approval date, date of injury, details of injury, details of services provided per claimant, such as date, cost, for physician consultations, imaging referrals); and claimant (worker) variables (age group (15–24 years, 25–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, >65 years), gender (male, female), employer size (small (<$A1 million annual turnover), medium ($A1–20 million annual turnover), large (>$A20 million annual turnover, government)), employment type (full-time (≥35 hours/week), part-time, casual, other), Australian Standard Classification of Occupations occupation category (clerical, professional, labourer, manager, tradesperson)21). Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage socioeconomic status (in quintiles)22 and Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia remoteness (major city, inner regional, outer regional and remote23)) defined by a workers’ postcode.

oemed-2023-109369supp001.pdf (201.7KB, pdf)

Medicines data set

Medication variables available included drug name, drug Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code, drug strength, pack size dispensed, service cost, year of claim, claimants’ approval date. Gabapentinoids were either pregabalin or gabapentin (ATC code N02BF). Gabapentinoid dispensing were reimbursed for 1-month prior to the claim approval date to 24 months post claim date, the last available date in the data set. Medicines considered for pain management included ATC codes of M01, M02, M03, N01, N02, N03, N05, N06.

Data management

Following an agreement with the regulator of the compensation system, WorkSafe Victoria, data were received and analysed using established secure protocols. Researchers conducting the analyses were granted access to the data stored on Monash University’s virtual server platform and analyses conducted within Monash’s Secure eResearch Platform. A summary of high-level collated analyses was exported from the environment.

Data synthesis

Claimant variables are described per data category except for socioeconomic status, which were grouped into categories of most disadvantaged (quintile 1), middle three quintiles and most advantaged (quintile 5). The number of days to a first dispensing claim of a gabapentinoid was determined from the insurer received date for the claim to the date associated with the first gabapentinoid dispensing. A new episode of gabapentinoid use was considered if there were more than 60 days between gabapentinoid dispensing. Where present, missing data are reported per variable (n/N (%)). There were no missing data related to medicine variables.

Analyses

The characteristics of the claimant population were described with proportions (n/N (%)), means and SD or median and IQR as appropriate. The proportion of claimants who claimed a gabapentinoid was determined per year. A Poisson model examined gabapentinoid dispensing over time, adjusting for all available covariates with a log link and offset by the log of the number of total claims, reported as prevalence ratio with 95% CIs. A negative binomial model determined associations with the number of gabapentinoids dispensed per claimant adjusted for all available covariates and reported as an incidence rate ratio with 95% CI. A Cox proportional hazards model determined associations with the time to first gabapentinoid dispense per claimant adjusted for all available covariates and reported as HR with 95% CI. Statistical analyses were conducted in R V.4.2.2 (Vienna, Austria).

Results

The final sample included 17 689 low back pain claimants. The sample is described in table 1. Of the low back claimants, there were 159 654 dispensing claims for any type of medicine considered for pain management. Analgesics (N02) were the most common medication dispensed (n=97 598, 61.1%).

Table 1.

Description of low back pain claimants (n=17 689) and those dispensed at least one gabapentinoid between 2010 and 2017

| Characteristic | Low back pain claimants | Low back pain claimants dispensed at least one gabapentinoid | ||

| N (%) | N (% back pain claims) | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Total | 17 689 (100) | 2608 (100) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 6301 | 876 (13.9) | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.04) | 0.474 |

| Male | 11 388 | 1732 (15.2) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Age group | ||||

| 15–24 years | 1514 (8.6) | 105 (6.9) | 0.77 (0.65 to 0.91) | 0.016 |

| 25–34 years | 3846 (21.7) | 520 (13.5) | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.02) | 0.260 |

| 35–44 years | 4492 (25.4) | 777 (17.3) | 1.02 0.94 to 1.09) | 0.771 |

| 45–54 years | 4724 (26.7) | 761 (16.1) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| 55–64 years | 2878 (16.3) | 416 (14.5) | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.02) | 0.247 |

| 65 or more years | 235 (1.3) | 29 (12.3) | 0.94 (0.71 to 1.25) | 0.747 |

| Employer size | ||||

| Small | 4137 (23.4) | 672 (16.2) | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.16) | 0.148 |

| Medium | 7161 (40.5) | 1058 (14.8) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Large | 4805 (27.2) | 706 (14.7) | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.10) | 0.679 |

| Government | 679 (3.8) | 99 (14.6) | 1.06 (0.90 to 1.25) | 0.592 |

| Missing | 907 (5.1) | 73 (8.0) | – | – |

| Employment type | 1.02 (0.85 to 1.22) | 0.918 | ||

| Casual | 262 | 47 (17.9) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Full-time employee | 12 137 | 1869 (15.4) | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.06) | 0.532 |

| Part-time employee | 3071 | 417 (13.6) | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.06) | 0.576 |

| Others | 2219 | 275 (12.4) | ||

| Occupation (ASCO) | ||||

| Advanced clerical and service workers | 160 (0.9) | 14 (8.8) | 0.78 (0.52 to 1.19) | 0.369 |

| Associate professionals | 1778 (10.0) | 215 (12.1) | 0.98 (0.86 to 1.13) | 0.852 |

| Elementary clerical, sales and service workers | 714 (4.0) | 115 (16.1) | 1.12 (0.97 to 1.29) | 0.283 |

| Intermediate clerical, sales and service workers | 2259 (12.8) | 304 (13.5) | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.07) | 0.579 |

| Intermediate production and transport workers | 3476 (19.7) | 564 (16.2) | 1.02 (0.94 to 1.12) | 0.689 |

| Labourers and related workers | 3668 (20.7) | 553 (15.1) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Managers and administrators | 501 (2.8) | 96 (19.2) | 1.07 (0.90 to 1.26) | 0.569 |

| Professionals | 2008 (11.4) | 290 (14.4) | 1.07 (0.95 to 1.21) | 0.407 |

| Tradespersons and related workers | 3125 (17.7) | 457 (14.6) | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.16) | 0.377 |

| Socioeconomic status (IRSAD) | ||||

| Most advantaged | 3046 (17.2) | 354 (11.6) | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.05) | 0.535 |

| Middle three quintiles | 11 742 (66.4) | 1747 (14.9) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Most disadvantaged | 2868 (16.2) | 498 (17.4) | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.07) | 0.885 |

| Missing | 33 (0.2) | 9 (27.3) | – | – |

| Remoteness (ARIA) | ||||

| Major cities | 12 830 (72.6) | 1841 (14.3) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Inner regional | 4022 (22.7) | 647 (16.1) | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.15) | 0.122 |

| Outer regional and remote | 818 (4.6) | 115 (14.1) | 0.94 (0.81 to 1.09) | 0.562 |

| Missing | 19 (0.1) | 5 (26.3) | – | – |

| Dispensed opioid analgesics (N02) | ||||

| Dispensed an opioid analgesic(s) | 5541 (31.3) | 2365 (42.7) | 14.07 (12.18 to 16.24) | <0.001 |

| No opioid analgesics | 12 148 (68.7) | 243 (2.0) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Dispensed anti-depressants (N06A) | ||||

| Dispensed an anti-depressant(s) | 2476 (14.0) | 1466 (59.2) | 2.24 (2.09 to 2.39) | <0.001 |

| No anti-depressants | 15 213 (86.0) | 1142 (7.5) | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Received any pain-related medicine* | – | – | – | |

| Dispensed any pain medicine | 6344 (35.9) | 2519 (39.7) | – | – |

| No other pain medicine (ie, excluding N02BF) | 11 345 (64.1) | 89 (0.8) | – | – |

*Medicine used for pain management included Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes of M01 (anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products, non-steroids), M02 (topical products for joint and muscular pain), M03 (muscle relaxants), N01 (anaesthetics), N02 (analgesics), N03 (anti-epileptics), N05 (psycholeptics), N06 (psychoanaleptics). ATC code of N06A are anti-depressants, and N02BF are gabapentinoids.

ARIA, Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia; ASCO, Australian Standard Classification of Occupations; IRSAD, Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage.

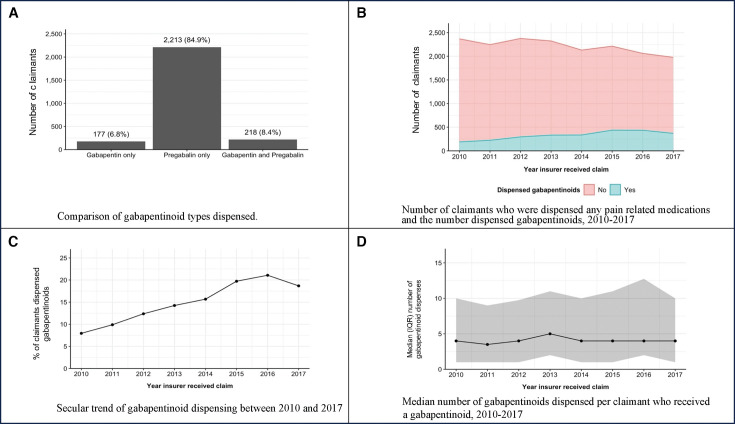

One in seven low back claimants were dispensed a gabapentinoid at least once during the first 2 years of their claim (n=2608, 14.7%) (table 1). Pregabalin accounted for 84.9% of claimants dispensed a gabapentinoid (n=2608) (figure 1A). Gabapentin dispensing was small (n=177) and stable over time. Concomitant dispensing of both pregabalin and gabapentin at any time point was infrequent (n=218; 8.4%) (figure 1A). The proportion of claimants dispensed a gabapentinoid increased from 7.9% in 2010 to 21.7% in 2016 (p=0.041) (figure 1C). Yearly values are presented in online supplemental appendix 2. Gabapentinoid dispensing was significantly associated with opioid analgesic and anti-depressant dispensing, but not any claimant-level characteristics (table 1).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of gabapentinoid dispensing. (A) Comparison of gabapentinoid types dispensed. (B) Yearly gabapentinoid dispensing out of all pain-related medicines. (C) Secular trend of gabapentinoid dispensing between 2010 and 2017. (D) Number of gabapentinoid dispensed per claimant over time.

Gabapentinoid dispensing increased over time despite reducing the number of low back pain claimants being dispensed pain-related medicines (figure 1B). The majority of workers who were dispensed gabapentinoids were also dispensed an opioid analgesics(s) during their claim (90.7%, n=2365). Of those 2365 workers, 67.3% were dispensed opioids prior to gabapentinoids (online supplemental appendix 4). Online supplemental appendix 4 details the proportion of workers who dispensed other pain medicines before or after their gabapentinoid dispensing.

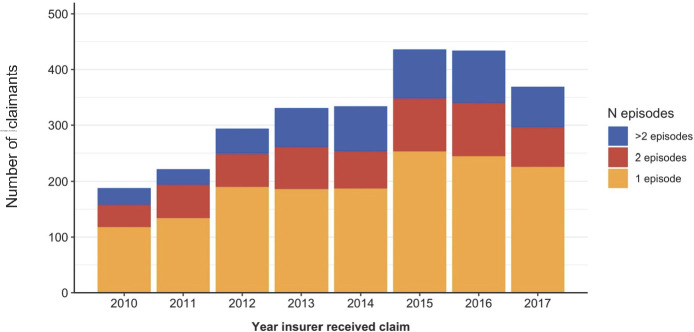

Most claimants had one episode of gabapentinoid dispensings (figure 2, online supplemental appendix 3). The mean number of gabapentinoid dispensing per claimant was 7.4 (SD 8.2). A lower number of dispenses per claimant was associated with those who were older (65 years or older) (p=0.034) compared with those 45–54 years; tradespersons occupation compared with labourers (p=0.270); those in most advantaged economic categories compared with the middle quintiles (p=0.003); and those living within inner regional areas compared with claimants living in major cities (p=0.078). Other claimant characteristics were not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Number of episodes per claimant over time. A new episode of gabapentinoid use was considered if there was more than 60 days between gabapentinoid dispensing.

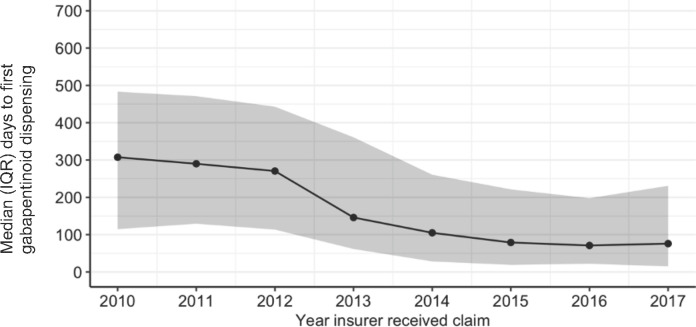

The time to first gabapentinoid dispensing significantly decreased over time (figure 3, online supplemental appendix 2). The mean number of days to first dispensing was 311.9 days (SD 200.7) in 2010 and reduced to 148.2 days (SD 183.1 days) in 2017. The initial sharp decline in days to the first dispensing occurred between 2012 and 2013, which coincides with pregabalin becoming available on the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS) in Australia (a government scheme that subsidises medicines). A lesser number of days to first gabapentinoid dispensing was associated with claimants who were part-time workers compared with full-time workers (p=0.033); those in tradespersons (p=0.048), professional (p=0.013), managers and administrator (p=0.004) occupations compared with labourers; and those in outer regional and remote areas compared with major cities (p=0.023). Other claimant characteristics were not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Median number of days to first gabapentinoid dispensing over time.

There was minimal change over time in the proportion of claimants dispensed one gabapentinoid compared with multiple dispensing (figure 1D). All gabapentinoids dispensed were for standard pack sizes, for example, 56 capsules for pregabalin, and 100 tablets for gabapentin. Pregabalin 75 mg and 150 mg capsules were the most commonly dispensed capsule strength. The mean cost of pregabalin dispensing was $A43.58 (SD $A33.72) and gabapentin $A37.18 (SD $A30.35), which represents a standard full-cost, private fee.

Discussion

In workers with a low back pain claim, the proportion of claimants being dispensed at least one gabapentinoid during their claim increased over time despite the number of claimants being dispensed pain-related medicines decreasing. There was a significant association of a gabapentinoid dispensing with a previous opioid analgesic and anti-depressant dispensing and not claimant-level characteristics like sex, socioeconomic status or geographical location. Although the number of dispenses per claimant was stable over time, the time to first gabapentinoid dispensing became shorter over time.

Gabapentinoids play a role in managing their indicated conditions12 which is supported by several clinical guidelines.24 However, their use for other conditions can be limited and may provide low-value care. For example, in patients with sciatica, gabapentinoids may be considered as providing low-value care as they do not provide any more benefit than a placebo, only more adverse events.17 This is a similar case for patients with low back pain.25 26 Subsequently, many updated clinical guidelines now do not support gabapentinoid prescribing in these conditions.5 While other guidelines do not commit to a recommendation due to variations in patient preferences despite acknowledging that gabapentinoid abuse and dependence outweigh the benefits compared with placebo for patients with low back pain with or without radicular symptoms.27 The sequela of gabapentin being the 10th most commonly prescribed medication in 2017 in the USA28 and global increased gabapentinoid prescribing14 18 19 is the increased incidence of serious harms, such as associated deaths,10 11 29 30 misuse31 32 and non-medical use.33–35 In Australia, pregabalin became available on the PBS in March 2013, which saw a rapid increase in prescribing36 and it has continued for the proceeding years.37 By 2020, pregabalin had become the most supplied analgesic in Australia.37 Increased prescribing in Australia has also occurred to patients presenting to general practitioners with spinal pain15 with a similar secular trend found in our study. The increased prescribing of gabapentinoids may be associated with clinicians trying to provide a non-opioid alternative following widespread recognition of the risk of harm with opioids while still providing analgesic options to the presenting patient.13

There is limited literature on the extent of gabapentinoid use in workers’ compensation populations. Previous North American data has shown an increase in gabapentinoid prescribing between 2008 and 2018,20 similar to our study and over a similar period. However, one noticeable difference is the contrasting prescribing of the two gabapentinoids. Furthermore, the difference in drug prescribing may be related to the difference in included participants; our study was limited to low back pain-related injuries compared with all types of workers’ compensation injuries.20 While compensation data from Louisiana, USA, between 1998 and 2007, saw that almost all participants (98%) did not receive a gabapentinoid within the first 6 months of their claim.38 When a gabapentinoid was prescribed, it was associated with prolonged claim costs at 6 months.38

Our study is the first to report trends in gabapentinoid use in a low back pain workers compensation population. Our results are from a robust, large, externally validated database documenting claimant activity since 1996 with very minimal missing data in our data set. Our data source has the advantage over other databases as the medicine-related data is directly linked to individual claimants’ history, and hence we could determine utilisation to a specific diagnostic condition. We acknowledge there are limitations to our study. Due to the nature of the database, the data reflects only medicines available for reimbursement and does not consider medicines a claimant already had at home. Therefore, some claimants may have greater actual medicine utilisation, such as using complementary medicines. Also, our sample most likely does not include acute low back pain presentations as claimants in the database have already had 10 business days off work to be eligible for reimbursement.

There is minimal research evaluating gabapentinoid use in the workers’ compensation population. This leaves opportunities for future research. Future research could expand our research by collecting longitudinal patient-reported outcomes, such as determining any associations between gabapentinoid use in injured workers and activities of daily living, mental health, adverse events, etc. These analyses may uncover if over time workers compensation populations are at increased risk of pregabalin overdoses, a characteristic noted more frequently associated with men.11 30 Additionally, future analyses may investigate if co-prescribing gabapentinoids with other high-risk drugs like opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines, a triad of drugs that can have serious health consequences (eg, death, intentional or unintentional poisonings, hospitalisations), is a concern in the worker compensation population as it has been identified in the care seeing39 and general population.40

Acknowledgments

This paper uses data supplied by WorkSafe Victoria. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of WorkSafe Victoria. MFDD is supported by a project grant from the New South Wales State Insurance Regulatory Authority. AC is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT19010218).

Footnotes

@DrSMathieson, @michaelfdd

Contributors: SM and CGM conceived the review. SM, AC, CGM, CAS, TX, SG, GEF and MFDD contributed to developing the protocol. AC and MFDD acquired data. SM and MFDD conducted analyses. SM, AC, CGM, CAS, TX, SG, GEF and MFDD contributed to the results interpretation. SM drafted the manuscript. MFDD is the guarantor of the study. All authors contributed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1171459).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. Data used in this paper are not available for distribution by the authors.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study received ethics approval from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID 30718). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Ferreira ML, de Luca K, Haile LM. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol 2023;5:e316–29. 10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00098-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen S, Chen M, Wu X, et al. Global, regional and national burden of low back pain 1990-2019: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. J Orthop Translat 2022;32:49–58. 10.1016/j.jot.2021.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kyung M, Lee SJ, Collman N, et al. Filing a workers' compensation claim for low back pain and associated factors: analysis of 2015 national health interview survey. J Occup Environ Med 2022;64:e585–90. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Di Donato M, Buchbinder R, Iles R, et al. Comparison of compensated low back pain claims experience in Australia with limb fracture and non-specific limb condition claims: a retrospective cohort study. J Occup Rehabil 2021;31:175–84. 10.1007/s10926-020-09906-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Low back pain and sciatica in over 16S: assessment and management. 2020. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59 [Accessed 19 Oct 2023]. [PubMed]

- 6. Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Furlan AD, et al. Prescription dispensing patterns before and after a workers' compensation claim: an historical cohort study of workers with low back pain injuries in British Columbia. J Occup Environ Med 2018;60:644–55. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Webster BS, Verma SK, Gatchel RJ. Relationship between early opioid prescribing for acute occupational low back pain and disability duration, medical costs, subsequent surgery and late opioid use. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2127–32. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318145a731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Koehoorn M, et al. Relationship between early prescription dispensing patterns and work disability in a cohort of low back pain workers' compensation claimants: a historical cohort study. Occup Environ Med 2019;76:573–81. 10.1136/oemed-2018-105626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freeman A, Davis KG, Ying J, et al. Workers' compensation prescription medication patterns and associated outcomes. American J Industrial Med 2022;65:51–8. 10.1002/ajim.23306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darke S, Duflou J, Peacock A, et al. Characteristics of fatal gabapentinoid-related poisoning in Australia, 2000-2020. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2022;60:304–10. 10.1080/15563650.2021.1965159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Evoy KE, Covvey JR, Peckham AM, et al. Reports of gabapentin and pregabalin abuse, misuse, dependence, or overdose: an analysis of the food and drug administration adverse events reporting system (FAERS). Res Social Adm Pharm 2019;15:953–8. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Viatris . Austrlian product information - Lyrica (Pregabalin). 2022. Available: https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepositorynsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2010-PI-04219-3&d=20230922172310101 [Accessed 19 Oct 2023].

- 13. Goodman CW, Brett AS. Gabapentin and pregabalin for pain - is increased prescribing a cause for concern? N Engl J Med 2017;377:411–4. 10.1056/NEJMp1704633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schaffer AL, Busingye D, Chidwick K, et al. Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012 to 2018. BJGP Open 2021;5. 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mathieson S, Valenti L, Maher CG, et al. Worsening trends in analgesics recommended for spinal pain in primary care. Eur Spine J 2018;27:1136–45. 10.1007/s00586-017-5178-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Elshaug AG, Rosenthal MB, Lavis JN, et al. Levers for addressing medical underuse and overuse: achieving high-value health care. Lancet 2017;390:191–202. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32586-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mathieson S, Maher CG, McLachlan AJ, et al. Trial of pregabalin for acute and chronic sciatica. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1111–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1614292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ashworth J, Bajpai R, Muller S, et al. Trends in gabapentinoid prescribing in UK primary care using the clinical practice research datalink: an observational study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2023;27:100579. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chappuy M, Nourredine M, Clerc B, et al. Gabapentinoid use in French most precarious populations: insight from Lyon permanent access to healthcare (PASS) units, 2016-1Q2021. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2022;36:448–52. 10.1111/fcp.12726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu C, Lavin RA, Yuspeh L, et al. Gabapentinoid and opioid utilization and cost trends among injured workers. J Occup Environ Med 2021;63:e46–52. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations. Version 12. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Australian Bureau of Statistics . Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA) 2011 ABS catalogue No.2033.0.55.001. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Department of Health and Aged Care . Measuring remoteness: accessibility/remoteness index of Australia (ARIA) revised edition. Occasional papers: new series number 14. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings. clinical guideline [CG173]. 2020. Available: https://wwwniceorguk/guidance/cg173 [Accessed 27 Feb 2024]. [PubMed]

- 25. Shanthanna H, Gilron I, Rajarathinam M, et al. Benefits and safety of gabapentinoids in chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002369. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Enke O, New HA, New CH, et al. Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2018;190:E786–93. 10.1503/cmaj.171333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Department for Veterans Affairs/ Department of Defense (VA/DoD) . Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Version 3.0. 2022. Available: https://wwwhealthqualityvagov/guidelines/Pain/lbp/VADoDLBPCPGFinal508pdf [Accessed 27 Feb 2024].

- 28. The IQVIA Institute . Medicine use and spending in the U.S.: a review of 2017 and outlook to 2022. 2018. Available: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-use-and-spending-in-the-us-review-of-2017-outlook-to-2022 [Accessed 27 Jun 2023].

- 29. Nahar LK, Murphy KG, Paterson S. Misuse and mortality related to gabapentin and pregabalin are being under-estimated: a two-year post-mortem population study. J Anal Toxicol 2019;43:564–70. 10.1093/jat/bkz036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cairns R, Schaffer AL, Ryan N, et al. Rising pregabalin use and misuse in Australia: trends in utilization and intentional poisonings. Addiction 2019;114:1026–34. 10.1111/add.14412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goins A, Patel K, Alles SRA. The gabapentinoid drugs and their abuse potential. Pharmacol Ther 2021;227:107926. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Evoy KE, Sadrameli S, Contreras J, et al. Abuse and misuse of pregabalin and gabapentin: a systematic review update. Drugs 2021;81:125–56. 10.1007/s40265-020-01432-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fonseca F, Lenahan W, Dart RC, et al. Non-medical use of prescription gabapentinoids (Gabapentin and Pregabalin) in five European countries. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:676224. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.676224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hägg S, Jönsson AK, Ahlner J. Current evidence on abuse and misuse of gabapentinoids. Drug Saf 2020;43:1235–54. 10.1007/s40264-020-00985-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Driot D, Jouanjus E, Oustric S, et al. Patterns of gabapentin and pregabalin use and misuse: results of a population-based cohort study in France. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2019;85:1260–9. 10.1111/bcp.13892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee . DUSC meeting, Pregabalin: 12 Month predicted versus actual analysis 2014. Available: https://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/participants/public-release-docs/2014-10/pregabalin-10-2014 [Accessed 27 Jun 2023].

- 37. Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme . Drug utilisation sub-committee (DUSC) opioid analgesics pregabalin. 2020. Available: https://wwwpbsgovau/info/industry/listing/participants/public-release-docs/2020-02/opioid-analgesics [Accessed 27 Jun 2023].

- 38. Tao XG, Lavin RA, Yuspeh L, et al. Drug prescription patterns as predictors of final workers compensation claim costs and closure: an updated analysis on an expanded cohort. J Occup Environ Med 2022;64:1046–52. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schaffer AL, Brett J, Buckley NA, et al. Trajectories of pregabalin use and their association with longitudinal changes in opioid and benzodiazepine use. Pain 2022;163:e614–21. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Penington Institute . Australia’s annual overdose report. Melbourne: Penington Institute; 2023. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

oemed-2023-109369supp001.pdf (201.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. Data used in this paper are not available for distribution by the authors.