Abstract

Depression is a prevalent psychological condition with limited treatment options. While its etiology is multifactorial, both chronic stress and changes in microbiome composition are associated with disease pathology. Stress is known to induce microbiome dysbiosis, defined here as a change in microbial composition associated with a pathological condition. This state of dysbiosis is known to feedback on depressive symptoms. While studies have demonstrated that targeted restoration of the microbiome can alleviate depressive-like symptoms in mice, translating these findings to human patients has proven challenging due to the complexity of the human microbiome. As such, there is an urgent need to identify factors upstream of microbial dysbiosis. Here we investigate the role of mucin 13 as an upstream mediator of microbiome composition changes in the context of stress. Using a model of chronic stress, we show that the glycocalyx protein, mucin 13, is selectively reduced after psychological stress exposure. We further demonstrate that the reduction of Muc13 is mediated by the Hnf4 transcription factor family. Finally, we determine that deleting Muc13 is sufficient to drive microbiome shifts and despair behaviors. These findings shed light on the mechanisms behind stress-induced microbial changes and reveal a novel regulator of mucin 13 expression.

Keywords: Mucins, Mucin 13, Depression, Microbiome, Despair behavior, Chronic stress

1. Introduction

Depression and anxiety impact millions of people worldwide (Santomauro et al., 2021). Although many treatments for these disorders exist, high rates of treatment-resistant cases remain. With up to 60% of patients unable to find satisfactory symptom resolution, the need for further investigation into novel therapeutic treatments is high (Fava, 2003). While the etiology of depression remains complex, one of the largest known contributing factors is stress (Heim and Binder, 2012; McGonagle and Kessler, 1990). Stress and depression are both associated with changes in the gut microbiome, and alterations in gut microbiome composition are present in depressed patients and conserved in animal models of depression (Lach et al., 2018; Foster and McVey Neufeld, 2013). Due to this, the microbiome has been extensively targeted as a potential treatment for mental health disorders: modification of the microbiome has been shown to reduce depression symptoms in humans and depressive-like behaviors in mice (Marin et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2022; Berding and Cryan, 2022; Valles-Colomer et al., 2019). While promising, efforts to broadly manipulate the human microbiome remain inconsistent due to the microbiome’s complexity, unknown microbe-microbe interactions, therapeutic microbes failing to colonize, microbe resource availability, and host heterogeneity (Berding and Cryan, 2022; Park et al., 2022; Zmora et al., 2018). To circumvent current microbiome therapeutic limitations and increase chances of successful microbial alterations in patients, there is a critical need to identify key conserved, targetable regulators of the microbiome.

The mucus layer is critical to maintaining both intestinal homeostasis and overall health. In the absence of mucus proteins, known as mucins, sweeping microbiome changes and spontaneous disease occur (Borisova et al., 2020; Hansson, 2020; Johansson et al., 2011; Van der Sluis et al., 2006; Velcich et al., 2002). Mucins are highly glycosylated proteins that fall into two categories: soluble mucins and transmembrane mucins (Hansson, 2020; Johansson MEVaH, G. C. The Mucins, 2016). While soluble mucins make up the gel-like layer that is commonly associated with mucus, transmembrane mucins remain tethered to the cell membrane (Hansson, 2020; Pelaseyed and Hansson, 2020). In the intestines, mucin 2 is the dominant soluble mucin, while mucin 13 and mucin 17 primarily represent the intestinal transmembrane mucins (collectively known as the glycocalyx) (Hansson, 2020; Pelaseyed and Hansson, 2020). Both soluble and transmembrane mucins have important roles in regulating the intestine and microbiome (Hansson, 2020). The mucus layer provides both a food source and anchor point for intestinal bacteria (Hansson, 2020). Recent works have demonstrated that the mucus layer drives the stability and composition of the microbiome by providing a permissive state for bacterial growth and selecting for specific bacteria along the intestines via varying availability of glycan chains (Van Herreweghen et al., 2020; Duncan et al., 2021; Sicard et al., 2017; Werlang et al., 2019). Supporting this idea, deletion of core 1 O-glycans in mice results in dramatic alterations of the microbiome composition and spontaneous colitis (Sommer et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2011).

Mucin expression is responsive to a variety of signals such as inflammation, infection, microbial products, and stress hormones (Hansson, 2020; Wheeler et al., 2019. Epub 2019/10/16.; Cairns et al., 2017; van Putten and Strijbis, 2017; Sheng et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2014). Specifically, stress hormones have been shown to alter the glycosylation patterns of mucins (Sommer et al., 2014; Silva et al., 2014; Biol-N’garagba et al., 2003). As changes in glycosylation have also been shown to change microbiome composition, these reports support the concept that stress may induce alterations in the mucus layer in a way that changes the microbial niche (Werlang et al., 2019; Kudelka et al., 2020; Bergstrom et al., 2020; Gamage et al., 2020). However, to date, no studies have attempted to understand the relationship between stress, mucin expression, and microbiome changes.

Given the strong evidence supporting the role of the mucus layer in microbiome homeostasis and regulation, as well as the known ways in which stress can alter mucin glycosylation, we hypothesized that exposure to chronic stress alters the mucus layer to initiate microbiome changes. Here, we demonstrate that a model of chronic stress, in addition to altering the microbiome, selectively alters the expression of transmembrane mucin, mucin 13. This change is not observed after microbiome transfer from “stressed” mice into antibiotic treated or germ-free animals. This suggests that mucin 13 expression is not reduced by changes in the microbiome, but rather another mechanism regulates its expression. In addition, we demonstrate the transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF4) regulates Muc13 expression by binding the Muc13 promoter. Supporting this, deletion of Hnf4 dramatically reduced Muc13 expression. Finally, we demonstrate that deletion of Muc13 induces baseline despair behaviors, renders animals more susceptible to anxiety-like behaviors, and alters microbial signatures in a way that mimics the composition of microbes after stress exposure. Together, these findings suggest that Mucin 13 and HNF4 are mechanistic upstream regulators of stress-induced microbiome shifts.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (strain #000664 and #000651, respectively). Mice were bred in-house and kept on a 12-h light/dark schedule. All mice were group housed up to 5 mice per cage unless separated for fighting, the only male pup in a litter, or designated to a stressed group, where they were singly housed. All behavioral interventions were performed between 8 am and 3 pm and animals were sacrificed between 7 am and 1 pm. For stress experiment euthanization, all mice were removed from the overnight stressor at 7am. Euthanization began immediately upon removal from the overnight stressor and continued until all animals were sacrificed. Experimental and control animals were sacrificed in alternating patterns to ensure proper controls for circadian consideration. Villin-CreERT2; Hnf4aF/F; Hnf4gCrispr/Crispr animals (Hnf4 DKO) were generated at Rutgers University under the care of the Verzi lab. Inducible knockouts for sequencing were given 1 injection of tamoxifen (50 mg/kg) for 2–3 days (2–3 total doses) to catch early changes in the intestines. HNF4 DKO mice used for qPCR were given 1 injection of tamoxifen (50 mg/kg) for 4 days (4 total doses). Animals were harvested on the 5th day. All control animals were given saline.

Mucin 13 knockout lines were generated using the iGONAD technique as described, using a BTX ECM 830 Electroporation System (Harvard Apparatus) (Gurumurthy et al., 2019; Ohtsuka et al., 2018). Briefly, the Muc13 sequence was taken from the UCSC genome browser, mouse assembly Dec. 2011 (GRCm38/mm10), Genomic Sequence (chr16:33,794,037–33,819,927) (Kent et al., 2002). Exons 1 and 2 including the intervening intron where analyzed with CRISPOR (http://crispor.tefor.net/; Concordet and Haeussler, 2018). Exon 2, containing the protein start sequence, was targeted for excision at two target sequences + PAM sites: Exon2_protein_start_sequence GCAA-GAGCAGCTACCATGAA (AGG) and Exon2_end_of_exon AGTCTCCTTTTGGTGACCGT (GGG). Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease, tracrRNA, and crRNA XT for the two target sequences were purchased (IDT). Prior to surgery, the Alt-R CRISPR/Cas9 reagents were prepared according to IDT guidelines: crRNA-XT and tracrRNA were annealed to form the gRNA, complexed to the S.p HiFi Cas9 nuclease, and then diluted with sterile Opti-MEM with Fast Green FCF to aid visualization.

Plugged females were anesthetized and maintained with isoflurane ~16 h after copulation was assumed to have occurred (estimated copulation around midnight, surgeries were done at 4 pm). Anesthesia was confirmed by toe pinch and eyes were lubricated with Puralube ointment. The lower dorsal skin of the mouse was soaked in betadine followed by two washes with isopropanol. A dorsal incision was made to expose the ovaries, oviduct, and uterine horn. Using a pulled micropipette, ~1.5 μL of the CRISPR/Cas9 solution was drawn up and then injected between the infundibulum and ampulla, intraoviductally dispensing the solution slowly to avoid backflow. The oviduct was covered in a wetted, sterile kimwipe and immediately electroporated using 3-mm platinum tweezer rode electrodes (BTX) delivering 50 V for 5 ms with 1 s interval for 8 square-wave pulses using a BTX ECM 830 Electroporation System (Harvard Apparatus). The oviduct was returned to the abdominal cavity and the procedure was repeated on the opposite side oviduct. Once both oviducts were injected and electroporated, the incision was sutured, and the stitches secured with liquid bandage before receiving a postop subcutaneous injection of ketoprofen (5 mg/kg of mouse body weight) with subsequent injections for up to five days as needed. All procedures were approved by the University of Virginia ACUC (protocol #3918). All experiments were conducted and reported according to ARRIVE guidelines.

2.2. Stress experiments and behavioral tests

Unpredictable Chronic Mild Restraint Stress (UCMRS) experiments and behavioral experiments (the forced swim, tail suspension, sucrose preference, open field, elevated plus maze, and nestlet shred tests) were performed as previously described. (Rivet-Noor et al., 2022).

Stress protocol:

For UCMRS, all animals were single housed. Mice were exposed to 2 h of restraint stress and one overnight stressor per day. Restraint stress was performed by putting mice into ventilated 50 mL conical tubes for 2 h. Overnight stressors included one of the following: 45-degree cage tilt, wet bedding, or 2x cage change. Wet bedding was performed by wetting standard cage bedding with ~200 mL of murine drinking water. 2x cage change included replacing cage bases 2x within 24 hr. 45-degree cage tilt included propping cages up to ~45-degrees overnight.

Behavioral tests:

All testing (with exception of the nestlet shred and sucrose preference tests) was recorded on a Hero Session 5 or 8 GoPro and analyzed with Noldus behavioral software.

Nestlet shred:

Mice were moved into fresh individual cages and allowed to habituate for 1 h. After 1 h, a weighed nestlet was placed in the center of the cage. Mice were allowed to interact with the nestlet for 30 min. After 30 min, nestlets were removed and weighed. Before weighing, excess nestlet was stripped from the main piece of nestlet by lightly dragging fingers across each area of the nestlet starting from the center (center up, center left, center right, center down). Once completed, nestlet was flipped and the process was repeated for the corners (center to upper right, center to upper left, center to lower right, center to lower left). Equal pressure was applied to each nestlet. Change in amount shredded and percent shredded were calculated from the weighed nestlet values.

Sucrose preference test:

Mice were housed individually and given 2 water bottles/cage. One water bottle contained normal drinking water, the other contained 1% sucrose water. Mice had access to the bottles for 3 days. On Day 0, bottles were primed, weighed, and put in cages. Day 1: 24 h later, water bottles were removed from cages and weighed. Once weighed, bottles were replaced, but with swapped positions (i.e.- if sucrose was on the left on Day 0, it was on the right on Day 1). The first night of sucrose preference is considered habituation and the values are not included in analysis. Day 2: 24 h after replacing water bottles, bottles were weighed and replaced as on day 1. Day 3: 24 h after replacing water bottles, bottles were removed and weighed for a final time. Sucrose preference was calculated by determining the percentage of each bottle drunk on day 2 and 3 and averaging those values.

Elevated plus maze:

Mice were placed on an elevated plus maze apparatus and allowed to explore for 5 min. The elevated plus maze was cleaned with 70% ethanol between each run and recorded on a GoPro Hero Session 5 or 8. Files were analyzed with Noldus behavior software.

Open field/DeepLabCut:

Animals were placed into a 14in × 14in box with opaque walls and a raised clear bottom (18in). Animals were allowed to explore freely for 10 min. Hero session 8 cameras were placed ~18in below the box to record animal movements from below. Noldus behavioral software was used to determine if animals were in the perimeter or center of the box. Videos were also used for DeepLabCut analysis. Analysis is described below.

2.3. Metabolite mass spectrometry

25 μL of serum was extracted using 500 μL of cold acetonitrile followed by vortexing and 10 min of centrifugation at 14K rpm. 450 μL of the resulting supernatant was transferred to a clean Eppendorf and dried completely by Speedvac. Each sample was reconstituted with 25 μL of 50% methanol in 0.1% formic acid/water, vortexed and transferred to autosampler vials for analysis by mass spectrometry. Eleven metabolites were quantitated by PRM (parallel reaction monitoring) using a Thermo Orbitrap ID-X mass spectrometer coupled to a Waters BEH C18 column (15 cm × 2.1 mm). Metabolites were eluted with a Vanquish UHPLC system over a 15 min gradient (10 μL injection, 200 μL/min, buffer A – 0.1% formic acid in water, buffer B – 0.1% formic acid in methanol). The mass resolution was set to 120K for detection using the transitions outlines in Extended Data Table 6.

Raw data files for samples, blanks, and calibration curves were imported into Skyline (https://skyline.ms/project/home/begin.view). Calibration curves were generated with a linear regression. Peak areas for analytes in samples were used for quantification based in the generated calibration curves. Raw files can be downloaded for analysis at https://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org under study ID: ST002345.

2.4. Intestinal tissue mass spectrometry

Frozen intestinal tissue sections were homogenized use the Cryo-Cup Grinder (BioSpec Products, Cat. No. 206) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Pulverized tissue was transferred into ice-cold 150 μL dialyzable lysis buffer, consisting of 1% N-octylglucoside (Research Products International, N02007), 1% CHAPS (Research Products International, C41010), 50 mM Tris (American Bio, AB14044), 100 mM NaCl (Research Products International, S23025), 2 mM MgCl2 (American Bio, AB09006), benzonase (Sigma Aldrich, E1014), and protease inhibitor (Roche, 11836170001). Samples were rotated at 4 °C for 2 h, followed by centrifugation for 30 min at 15,000 rcf and passed through a 0.7 μm filter. StcEE447D was expressed and purified as previously described (Malaker et al., 2019; Malaker et al., 2022). 500 μg of NHS-Activated Agarose Slurry (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 26200) was activated with 1 mM HCl and PBS. StcEE447D (1 mL of 1.45 mg/mL) was added to the slurry and rotated at 4 °C for 3 h. Beads were rinsed with 100 mM Tris and the reaction quenched with 100 mM acetate buffer. Beads were washed with 20 mM Tris. Beads were then washed and stored in 20 mM Tris 150 mM NaCl. Filtered supernatants were rotated overnight at 4 °C with 100 μL StcEE447D-NHS bead slurry and 0.01 M EDTA. All reactions were brought up to 1 mL with 20 mM Tris 150 mM NaCl. Beads were then rinsed with 10 mM Tris 1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaCl and MS grade water (Thermo Scientific, 51140). Protein was eluted with 1% sodium deoxycholate (Research Products International, D91500–25.0) in 50 mM Ammonium bicarbonate (AmBic) (Honeywell Fluka, 40867), at 95 °C for 5 min. Dithiothreitol (DTT) (Sigma Aldrich, D0632) was added to 20% of the eluent to a final concentration of 2 mM and allowed to react at 65 °C for 25 min. Alkylation in 5 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) (Sigma Aldrich, I1149) was performed for 15 min in the dark at room temperature. 0.05μg of sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega, V5111) was added to each 20% aliquot and allowed to react for 3 h at 37 °C. Reactions were quenched by adding 1 μL formic acid. All reactions were diluted to a volume of 100 μL prior to desalting. Desalting was performed using 10 mg Strata-X 33 μm polymeric reversed phase SPE columns (Phenomenex, 8B-S100-AAK). Each column was activated using 1 mL acetonitrile (ACN) (Honeywell, LC015) followed by of 1 mL 0.1% formic acid, 1 mL 0.1% formic acid in 50% ACN, and equilibration with addition of 1 mL 0.1% formic acid. After equilibration, the samples were added to the column and rinsed with 200 μL 0.1% formic acid. The columns were transferred to a 1.5 mL tube for elution by two additions of 150 μL 0.1% formic acid in 50% ACN. The eluent was then dried using a vacuum concentrator (LabConco) prior to reconstitution in 10 μL of 0.1% formic acid.

Samples were analyzed by online nanoflow liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using an Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Dionex UltiMate 3000 HPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For each analysis, 5 μL was injected onto an Acclaim PepMap 100 column packed with 2 cm of 5 μm C18 material (Thermo Fisher, 164564) using 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A). Peptides were then separated on a 15 cm PepMap RSLC EASY-Spray C18 Column packed with 2 μm C18 material (Thermo Fisher, ES904) using a gradient from 0 to 35% solvent B. (0.1% formic acid with 80% CAN) in 60 min.

Full scan MS1 spectra were collected at a resolution of 60,000, an automatic gain control of 1E5, and a mass range from 400 to 1500 m/z. Dynamic exclusion was enabled with a repeat count of 2 and repeat and duration of 8 s. Only charge states 2 to 6 were selected for fragmentation. MS2s were generated at top speed for 3 s. Higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) was performed on all selected precursor masses with the following parameters: isolation window of 2 m/z, stepped collision energies of 25%, 30%, 40%, orbitrap detection (resolution of 7500), maximum inject time of 75 ms, and a standard AGC target.

Label-free quantification was performed using the minimal workflow for MaxQuant according to the established protocol for standard data sets (Tyanova et al., 2016). Files were searched with fully specific cleavage C-terminal to an Arg or Lys residue, with 2 allowed missed cleavages. Carbamidomethyl Cys was set as a fixed modification. Raw data generated from each intestinal section was included and analyzed using Perseus, according to the recommended protocol for label-free interaction data (Fold change > 5 as the cutoff).

2.5. Fecal DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

DNA was isolated from fecal pellets using the phenol/chloroform method as described (Marin et al., 2017). Samples were then processed with QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen #28106). Full protocol is outlined below:

250 μL of 0.1 mm zirconia/silica beads (BioSpec #11079101z) were added to a sterile 2 mL screwtop tube (Celltreat #230830). One 4 mm steel ball was added to each tube (BioSpec #11079132ss). 500 μL of Buffer A (200 mM TrisHCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA) and 210 μL of 20% SDS were added to each fecal pellet in a separate 1.7 mL tube. Pellets were vortexed and supernatant transferred to the 2 mL screwtop tube containing beads. 500 μL of Phenol/chloroform/IAA were added to each screwtop tube. Tubes were allowed to beadbeat on high for 4 min at room temperature. Samples were then centrifuge at 12000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. 420 μL of the aqueous layer was transferred to a new 1.7 mL tube. 100 μL of the samples was then processed using the Qiagen PCR Purification Kit.

16S sequencing of 3 week UCMRS experiments:

The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified from each sample using a dual indexing sequencing strategy (Kozich et al., 2013). Samples were sequenced on the MiSeq platform (Illumina) using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (500 cycles, Illumina #MS102–2003) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with modifications found in the Schloss Wet Lab SOP (https://github.com/SchlossLab/MiSeq_WetLab_SOP).

All processing and analysis of 16S rRNA sequencing data was performed in R (version 4.1.2) (Team RC, 2021). Raw sequencing reads were processed for downstream analysis using DADA2 (version 1.22.0) (Callahan et al., 2016). Processing included inspection of raw reads for quality, filtering of low-quality reads, merging of paired reads, and removal of chimeric sequences. Length distribution of non-chimeric sequences was plotted to ensure lengths matched the expected V4 amplicon size. Taxonomy was assigned to amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) by aligning reads with the Silva reference database (version 138.1) (Quast et al., 2013).

Microbiota diversity and community composition were analyzed using the packages phyloseq (version 1.38.0), microbiome (version 1.16.0), and vegan (version 2.5.7) (Jari Oksanen et al., 2020; Leo Lahti; McMurdie and Holmes, 2013). The packages tidyverse (version 1.3.0), and ggplot2 (version 3.3.5) were used for data organization and visualization (Hadley Wickham et al., 2019; Wickham, 2016).

Random forest analysis was performed using the randomForest (version 4.6.14), vegan (version 6.0.90), and pROC (version 1.18.0) packages (Kuhn, 2021; Liaw A, 2002; Robin et al., 2011). Samples were first divided into training (70% of samples, divided equally between Baseline and stress samples) and test (30% of samples) sets. The training set was used to tune the “mtry” parameter of the model, while the test set was used to validate model performance. Feature importance was determined using the Gini index, which measures the total decrease in node impurity averaged across all trees. Custom code and detailed instructions can be found at: https://github.com/gbmoreau/Gautier-manuscript. Raw sequencing reads can be found in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under PRJNA867333.

2.6. Microbiome transfer experiments

Antibiotic microbiome transfer experiments were performed by treating mice with a cocktail of the following antibiotics: ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, A8351), neomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, N6386), metronidazole (Sigma-Aldrich, M1547), and vancomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, V1130). Ampicillin, neomycin, and metronidazole were added to water containing 8 g/L of a zero-calorie sweetener at 1 g/L. Vancomycin was added at 500 mg/L. Mice were allowed to drink ad libitum for two weeks and fresh antibiotic solutions were made once per week. After 2 weeks of antibiotic treatment, mice were given an oral gavage of 100 μL of either naïve or stressed fecal slurry (equal weights of collected fecal pellets homogenized in 4 mL PBS) every 2 days for a total of 4 gavage treatments (Fig. 2, panels E and F). Animals were allowed to habituate to the introduced microbiome for 14 days from the first gavage. Germ-free experiments where animals received stress or naïve fecal pellets were described previously (Merchak et al., 2024). Briefly, equal amounts of dirty bedding from naïve or stressed animals was transferred daily to germ-free animal cages for two weeks. After two weeks of dirty bedding transfer, animals were allowed to habituate to the transferred microbiome without further intervention for another two weeks.

2.7. 16S sequencing of microbiome transfer and 1 week UCMRS experiments

Fecal pellet DNA extraction and 16S sequencing of the V4 region was performed by Zymo according to their protocols. Raw sequencing reads can be found in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under PRJNA878703 and PRJNA866924, respectively.

2.8. Cell culture

HT-29 cells were purchased from ATCC and were grown in McCoy’s 5A media (ATCC 30–2007) as per the ATCC website. Cells were plated at a density of 150,000/well and allowed to adhere to 12 well plates overnight in complete media. Cells were treated with 10 μM of the HNF4 antagonist BI6015 (Sigma-Aldrich, 375240) or DMSO control for 24 h. After 24 h, media was aspirated, and cells were frozen at −80 °C until RNA extraction was performed.

2.9. RNA and ChIP seq experiments

All ChIP Seq experiments were performed previously on duodenal villus tissue as described (Chen et al., 2021a; Chen et al., 2019). Raw data can be found under GEO accession numbers GSE112946 (RNA-seq and ChIP-seq) and GSE148691 (HiChIP-seq).

2.10. DeepLabCut

DeepLabCut analysis was performed as previously described (Rivet-Noor et al., 2022). Full protocol is outlined below:

Animal pose estimation was performed on videos collected during the open field test by using a deep-learning package called DeepLabCut. The detailed mathematical model and network architecture for DeepLabCut was previously published by the Mathis lab (Mathis et al., 2018). We generated a DeepLabCut convolutional neural network to analyze our open field test videos which were trained in a supervised manner: 16 manually labeled points were selected as references of transfer learning, including: nose, left and right eyes, left and right ears, neck, left and right arm, left and right leg, 3 points on body, and 3 points on tail. In total, 15 randomly selected videos were used for building a training dataset. Once trained, DeepLabCut was applied to the collected sample videos and final pose estimations were made.

Estimated mouse poses from DeepLabCut were further analyzed by using a package called Variational Animal Motion Embedding (VAME), which classifies animal behavior in an unsupervised manner. VAME was developed by the Pavol Bauer group and the package can be downloaded at https://github.com/LINCellularNeuroscience/VAME (Luxem et al., 2020). We trained a unique VAME recursive neural network for each experiment, which classifies each frame of the open field test video into 1 of the 25 behavioral motifs. VAME is then applied to all experimental videos to categorize behaviors into 1 of 25 motifs. All behavior motifs were annotated, labeled, and evaluated by blinded human researchers. With annotated frames, we were able to calculate the percentage of time usage of each motif, which is then used for principal component analysis and Kullback-Leibler divergence analysis. Custom code is available upon request.

2.11. RNA extraction and quantitative PCR

For RNA extraction, cultured cells were pelleted, frozen, and lysed. RNA was extracted using the Bioline Isolate II RNA mini kit as per manufacture’s protocol (BIO-52073). RNA was quantified with a Biotek Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer. Normalized RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with either the Bioline SensiFast cDNA Synthesis Kit (BIO-65054) or Applied Sciences High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase Kit (43–688-13). cDNA was amplified using the Bioline SensiFast NO-ROX kit (BIO-86020), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Results were analyzed with the relative quantity (ΔΔCq) method. Most qPCR was performed with Taqman primers purchased from ThermoFisher (catalog numbers provided in Extended Data Table 5). For assays where commercial primers were not used, primer sequences are listed in Extended Data Table 5.

2.12. Immunofluorescence staining and imaging

1 cm sections of intestinal samples were harvested and snap frozen in an OCT block (Fisher Scientific #14-373-65). Samples were cut on a cryostat in 15 μM sections and placed on microscope slides. Tissue was fixed directly on the slides in carnoy’s solution (60% Ethanol, 30% Chloroform, and 10% Glacial Acetic Acid) for 10 min at room temperature. Tissue was washed in 1x PBS for 5 min 3x at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed with Tris-EDTA by bringing solution to a boil (~30sec) in a microwave. Slides were washed in 1x PBS 3x for 5 min at room temperature. After final wash, sections were outlined with a hydrophobic pen (Vector Laboratories #H-4000). Samples were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 1:200 FC block in TBST (1x TBS + 0.3 % Triton X-100) plus 2 % Normal Donkey Serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch #017-000-121). Supernatant was removed and samples were blocked with Mouse on Mouse IgG for 1 h at room temperature (Vector Laboratories #MKB-2213-1). Supernatant was removed and primary antibodies were added. Samples were stained with 1:1000 Mucin 13 (G-10) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #sc-390115) and 1:1000 Mucin 2 (GeneTex #GTX100664) overnight at 4 °C in blocking solution (1x PBS, 0.5 g bovine serum albumin, 0.5 % Triton X-100) + 2 % normal donkey serum. Control samples were stained in blocking solution + 2 % normal donkey serum with mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch #015-000-003) and rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch #011-000-003) diluted to match the primary antibody concentrations. The next day samples were washed in TBST for 5 min 3x at room temperature. Samples were then incubated in secondary antibodies for 3 h at room temperature in blocking solution + 2 % normal donkey serum. Secondary antibodies used were Donkey Anti-Mouse 488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch #715-545-150) and Donkey Anti-Rabbit 647 (Jackson ImmunoResearch #711-605-152). Secondaries were added at 2 mg/mL. Samples were then stained with Hoechst (1:700) (Thermo Fisher Scientific #H3570) for 15 min in blocking solution + 2 % normal donkey serum. Samples were washed 2x with TBST for 5 min at room temperature. Samples were washed a final time in TBS for 5 min at room temperature and cover-slipped. Finally, slides imaged on a Leica Stellaris 5 confocal microscope.

2.13. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses-except those associated with DeepLabCut, Mass Spectrometry, and 16S were performed in GraphPad Prism 9. Analyses comparing two groups were performed using a two-tailed T test. If the variances between groups were significantly different, a Welch’s correction was applied. Outliers were excluded based on the ROUT test in GraphPad Prism 9. For all analyses, the threshold for significance was at p < 0.05. Repeats for each experiment are specified in the figure legend corresponding to the respective panel and in Extended Data Table 4. Additional statistical detail, including all p-values, can be found in Extended Data Table 4.

3. Results

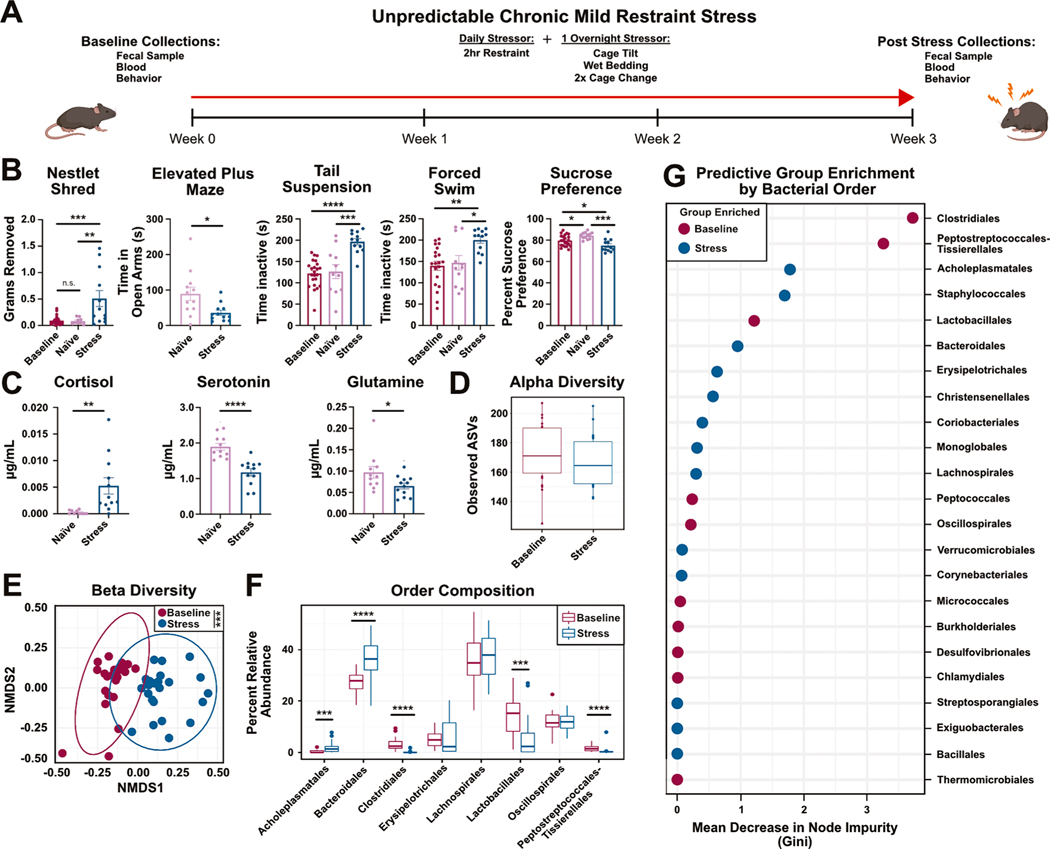

3.1. Unpredictable chronic mild restraint stress drives despair and anxiety-like behaviors and modifies the gut microbiome composition

To investigate the mechanisms of stress-induced microbiome alterations, we used unpredictable chronic mild restraint stress (UCMRS), a version of chronic stress known to induce anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors and alter gut flora (Fig. 1A) (Marin et al., 2017; Mineur et al., 2006). After three weeks, mice exposed to UCMRS showed a significant increase in anxiety-like behaviors characterized by an increase in nestlet shredding and decrease in time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze (Fig. 1B). Despair behaviors were also detected through an increase in time inactive in both the tail suspension and forced swim tests. Furthermore, a reduction in sucrose preference, a measure for anhedonia, was observed in UCMRS exposed mice (Fig. 1B). In addition to behavioral readouts, levels of murine stress- and depression- associated markers were measured from serum by mass spectrometry (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 1A–G). An increase in murine cortisol, but not corticosterone, was detected in stressed mice, confirming a robust chronic stress response (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. 1A). While murine stress responses are often associated with changes in corticosterone, mice also express cortisol to a lesser extent. (Dodiya et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2018). In addition, while elevations in corticosterone are abundant in acute models of stress, literature suggests that in chronic stress corticosterone levels return to baseline while higher cortisol levels are sustained (Gong et al., 2015). These works, in addition to our own data (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 1A), demonstrate that cortisol can be used as a measure for chronic stress response in mice. To further examine the impacts of UCMRS on stress and depressive-like responses in mice, we examined the presence of serotonin and glutamine in the serum of naïve or UCMRS exposed mice. Glutamine has been shown to be depleted in both models of chronic stress and animal models of depression, highlighting its reliability as a biomarker for true stress and depressive-like responses in mice (Baek et al., 2020; He et al., 2023; Pfleiderer et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2020). Serotonin depletion has also long been associated with depression in both humans and animal studies (Israelyan et al., 2019; Moncrieff et al., 2023; Vahid-Ansari and Albert, 2021). Consistent with our behavioral and cortisol data, decreases in both serotonin and glutamine were observed, further suggesting a true stress and depressive-like response after UCMRS exposure. No other molecules tested were changed (Supplementary Fig. 1A–G). These data highlight the validity of our model by demonstrating UCMRS induces changes in behavioral outputs and metabolites in mice that are consistent with human anxiety and depression.

Fig. 1.

Unpredictable chronic mild restraint stress induces despair and anxiety-like behaviors and microbiome dysbiosis: (A) Experimental design. (B) Nestlet shred (One-way ANOVA), elevated plus maze (t-test), tail suspension (One-way ANOVA), forced swim (One-way ANOVA), and sucrose preference (One-way ANOVA) tests between baseline, naïve controls, and stress animals. Male mice, n = 11/12 per group, representative of N = 2. (C) Targeted mass spectrometry from serum of naïve or stress animals (t-tests, n = 11/12 per group). (D) Alpha diversity plot showing microbial richness (observed ASVs) between baseline and stress mice (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test). (E) NMDS plot of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between baseline and stress fecal microbiome samples (PERMANOVA). (F) Relative abundances of bacterial orders > 1 % (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni correction). (G) Importance plot from a random forest model predicting bacterial orders that discriminate between baseline and stress groups. Importance is based on the Gini index where larger values are more important to model. Male mice, n = 24/group, N = 1.

We next evaluated stress-induced microbiome composition changes by performing 16S sequencing on fecal DNA from stressed and naïve animals. Using ASV-level data, we observed no differences in measures of alpha diversity (richness (Fig. 1D) or evenness (Supplementary Fig. 1H)). However, there were significant differences in ASV-level derived beta diversity between naïve and stressed animals (Fig. 1E). These differences were driven by changes in community composition at the ASV level; for clarity, bacterial orders are depicted. Consistent with our previous work, stress was associated with relative reductions in Clostridiales, Lactobacillales, and an expansion of Bacteroidales (Fig. 1F and Supplementary Fig. 1I) (Marin et al., 2017). Specific genus level changes between groups and the associated statistics can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1J and Extended Data Table 1. Lastly, an ASV based random forest model accurately predicted which bacterial orders were most influential in baseline or stressed groups, strengthening the link between stress and specific microbial shifts (Fig. 1G). The Gini index assesses the importance of a particular bacterial order in defining a group by examining how much of a decrease in purity, or accuracy, occurs when a bacterial order is removed for consideration. For example, the removal of Clostridiales from consideration when defining the Baseline group (Fig. 1G) results in a more impure (or less accurate) node in the random forest analysis. Orders that do not decrease node impurity are not expected to contribute to group identity and would not be expected to be different between groups. Taken together, these results demonstrate that unpredictable chronic mild restraint stress (UCMRS) induces despair and anxiety-like behaviors in mice, alters murine stress hormone levels, and induces composition shifts in the murine microbiome.

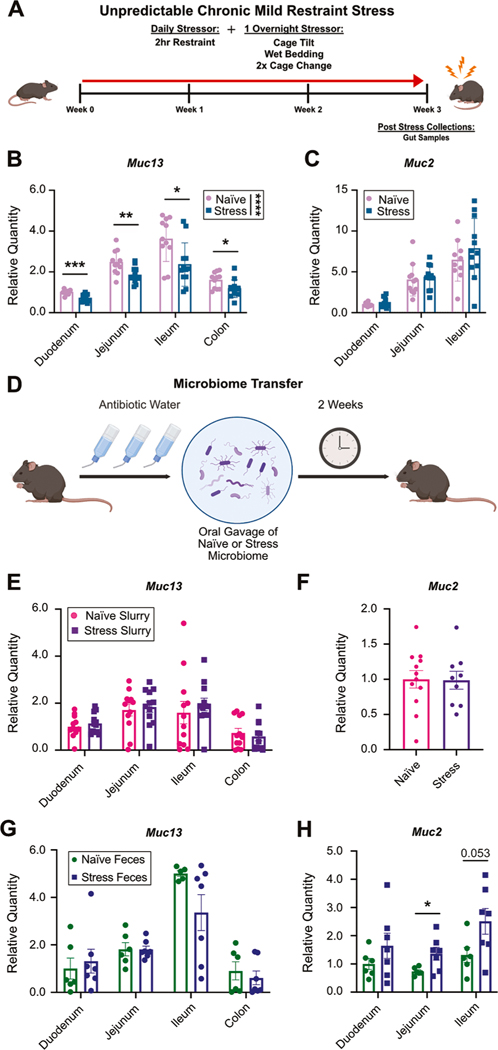

3.2. Unpredictable chronic mild restraint stress reduces Muc13 expression in vivo

While it is well accepted that stress can alter the microbiome in humans and mice (Fig. 1), the mechanisms behind these microbial shifts remain unknown (Bailey et al., 2011; Bastiaanssen et al., 2020; Berding and Cryan, 2022; Karl et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019). Because the mucus layer, primarily composed of heavily glycosylated mucins, provides both an anchor point and nutrient reservoir for bacteria, we hypothesized that a change in mucin composition could induce microbiome shifts (Hansson, 2020; Johansson, 2016; Pelaseyed and Hansson, 2020). To test this, we first evaluated if mucin expression changed in stressed conditions. Using RNA extracted from individual sections of the intestines of mice exposed to UCMRS and naïve controls (Fig. 2A), we examined mucin expression by qPCR. Of all the mucins examined (all detectable intestinal mucins: Muc1, 2, 4, 13, and 17), we found that Muc13 was uniquely reduced across intestinal segments (Fig. 2B–C and Supplementary Fig. 2A–C). Additionally, to examine mucin changes across genetic background, we examined Muc13 and Muc2 expression in BALB/cJ mice exposed to stress. We found a similar reduction in Muc13, while no changes in Muc2 expression were observed (Supplementary Fig. 2D–E). We then sought to examine mucin 13 changes at the protein level by mass spectrometry and immunofluorescence. However, due to the subtle changes observed in Muc13 transcript expression and the limitations in sensitivity and availability of mucin protein quantification techniques, we were unable to detect differences at the protein level. As quantifying mucin protein levels, especially subtle changes, remains challenging across the glycobiology field, changes in mucin transcript are well accepted as a readout for mucin changes (Harrop et al., 2012; Kesimer and Sheehan, 2012; Malaker et al., 2019, 2022; Tian et al., 2023). Given these known technical limitations and the consistent changes in mucin 13 transcript expression across experiments and genetic backgrounds, we proceeded to investigate the role of mucin 13 in stress-induced microbiome changes.

Fig. 2.

Stress drives Muc13 reductions independently of transferrable microbial products: (A) Experimental design. Relative quantity of (B) Muc13 and (C) Muc2 transcripts by qPCR in individual sections of the intestine in naïve and stress animals. Muc2 expression in the colon was higher than housekeeping genes preventing quantification by qPCR. Unpaired two-tailed, t-tests. Male mice, n = 11/12 per group, N = 2. (D) Experimental design for panels E and F. Relative quantity of (E) Muc13 and (F) Muc2 transcripts in the intestines of animals receiving a naïve or stress fecal microbiome slurry after antibiotic treatment via gavage. Male mice, n = 12 per group. T-tests, two-tailed. Relative quantity of (G) Muc13 and (H) Muc2 in the intestines of germ-free mice given naïve or stress fecal pellets. Male mice, n = 7 per group. T-tests, two-tailed.

3.3. Stress-induced Muc13 transcript reductions are driven independently of transferrable microbial products

The microbiome is a known influencer of the mucus layer. While we hypothesized that stress-induced changes in the mucus layer lead to changes in microbiome composition, we also considered that stress-induced shifts in the microbiome could instead be modulating Muc13 expression (Hansson, 2020; Sicard et al., 2017). If this was the case, it would suggest that mucin 13 expression changes occur after microbial shifts in our model. To test this hypothesis, we utilized two different models to examine the impacts of the microbiome on mucin 13 expression. First, after treating mice with antibiotics for two weeks, we transferred the fecal microbiomes from naïve or stressed animals via oral gavage (Fig. 2D). After allowing two weeks post reconstitution for microbiome stabilization, intestinal samples were collected to examine microbiome composition and mucin expression (Suez et al., 2018). 16S sequencing revealed that the donor slurries clustered distinctly from each other (Supplementary Fig. 2F, light blue and dark pink). In addition, recipient mice clustered nearer to their donor sample but separately from each other, demonstrating distinct microbiomes and successful transfer of the expected signatures (Supplementary Fig. 2F–G). We next examined RNA expression of intestinal mucins between groups. No change in mucin 13 expression was detected between animals that received a stressed or naïve microbiome (Fig. 2E). In addition, we saw no change in any other mucins expressed between groups (Fig. 2F and Supplementary Fig. 2H–J). These data demonstrate that microbial signatures from transferred stressed or naïve microbiomes are not sufficient to reduce mucin 13 expression.

To complement this approach, we also examined the impact of stressed microbial signatures on mucin expression in germ-free mice. Our lab has successfully demonstrated that microbial signatures from stressed mice can induce despair and anxiety-like behaviors in germ-free mice (Merchak et al., 2024). Therefore, using intestinal samples collected from germ-free mice which were given fecal pellets from naïve or stress-exposed animals, we again examined changes in mucin expression between groups by qPCR. Our results indicated that, like the antibiotic treated mice, no changes in Muc13 expression were observed between groups after colonization (Fig. 2G). This suggests that microbes from UCMRS exposed mice are not sufficient to induce mucin 13 expression changes in germ-free animals when compared to germ-free animals given microbes from naïve controls. In addition, while we saw no changes in Muc1, Muc4, or Muc17, we did see an expected increase in Muc2 expression with microbiome reconstitution in germ-free mice (Fig. 2H and Supplementary Fig. 2K–M) (Johansson et al., 2015). Taken together, these results demonstrate that microbial signatures from stressed animals, while able to induce behavioral changes, are not sufficient to reduce Muc13 expression in the intestines. This again suggests that the mucin 13 changes observed in stress are not driven by – and likely precede – microbial changes in the intestines. These results support our hypothesis that stress-induced reductions in mucin 13 are driven independently of transferrable microbial signatures.

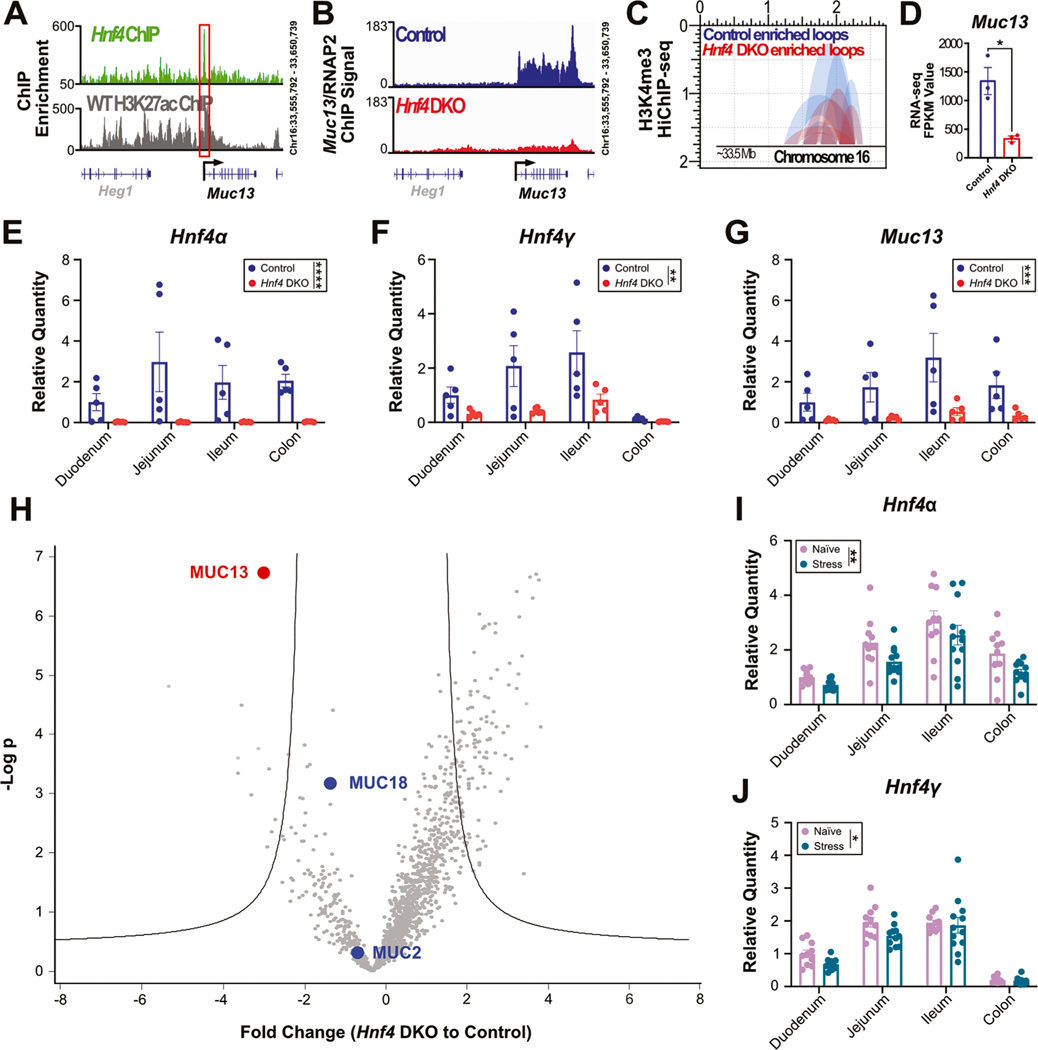

3.4. Muc13 reductions are driven by reductions in intestinal HNF4

To understand how stress induces reductions in Muc13 expression, we explored transcription factors which are known to bind to Muc13 by examining published small intestine and colon ChIP-seq data sets through the UCSC genome browser (Kent et al., 2002). Results revealed 10 transcription factors able to bind to the promoter region of Muc13 in both the small and large intestines (Ascl2; Cdx2, Hnf4α, Hnf4γ, Vdr, Med1, Pou2f3, Smad4, Ctcf, and Foxa1) (Chahar et al., 2014; Lickwar et al., 2022). Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF4), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, plays a critical role in regulating metabolism, epithelial tight junctions, and the differentiation and proliferation of enterocytes in the intestines (Babeu and Boudreau, 2014). In addition to these functions, Hnf4 expression has been shown to regulate the brush border, the collection of microvilli along the intestinal tract (Chen et al., 2021b). As the brush border is thought to be modulated by the density of the glycocalyx, and therefore transmembrane mucins, HNF4 is a prime candidate to mediate changes in Muc13 expression (Shurer et al., 2019). Importantly, stress hormones have also been shown to inhibit Hnf4 expression in a model of high fat diet (Lu et al., 2022). Together, these works provide a foundation for the hypothesis that stress may be able to regulate Hnf4 expression in a way that reduces Muc13 expression.

In order to investigate the ability of HNF4 to regulate Muc13 expression, we first analyzed previously performed HNF4 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq on wildtype duodenal villus cells to examine binding at the Muc13 locus (Chen et al., 2019). Results indicated that in wildtype mice, both HNF4 and H3K27ac, a marker of transcription, are enriched in the promoter region of Muc13 (Fig. 3A). This suggests that HNF4 binds the Muc13 promoter at a site that is marked for active transcription, supporting the idea that HNF4 can regulate Muc13 expression. We next wanted to examine the impacts of HNF4 deletion on Muc13 expression in the intestine. To do this, we utilized the previously described Villin-CreERT2; Hnf4aF/F; Hnf4g Crispr/Crispr double knockout line (Hnf4 DKO) which lacks both HNF4 paralogs (Chen et al., 2019). Analyzing previously performed RNA Polymerase II (RNAP2) ChIP-seq on duodenal villus epithelial cells in wildtype controls and Hnf4 DKO animals, we found that the RNAP2 signal at the Muc13 promoter is markedly reduced in the Hnf4 DKO animals compared to controls (Fig. 3B). To complement this approach, we further examined previously performed H3K4me3 chromosome conformation capture with chromatin immunoprecipitation (HiChIP) and RNA-seq on control and Hnf4 DKO duodenal villus epithelial cells (Chen et al., 2021). Analysis revealed fewer H3K4me3 chromatin loops in the Muc13 promoter region of Hnf4 DKO animals than in control duodenal villus epithelial cells, suggesting fewer sites of active transcription (Fig. 3C). In addition, RNA sequencing results showed a significant reduction in Muc13 expression in duodenal villus epithelial cells after the loss of Hnf4 (Fig. 3D). Hnf4 deletion did not reduce expression of any other detectable mucins by RNA-seq (Supplementary Fig. 3A–C). To validate these sequencing results, we next performed qPCR for mucin expression on all sections of the intestines from control and Hnf4 DKO animals. We found that in addition to the successful deletion of the Hnf4 paralogs (Fig. 3E–F), there was also a significant reduction in Muc13 expression across the intestines, validating the RNA-seq data (Fig. 3G). Given the dramatic reduction in Muc13 expression in Hnf4 DKO animals, we again sought to examine mucin 13 protein levels. To do this, we employed a mucin enrichment strategy that takes advantage of an inactive protease selective for mucin domains; mucins from Hnf4 DKO and control animal intestines were enriched and subjected to MS analysis (Malaker et al., 2019; Malaker et al., 2022). Confirming our RNA-seq and qPCR data, Hnf4 DKO animals had significant reductions in MUC13 protein expression across all sections of the intestine (Fig. 3H). Lastly, we analyzed intestinal expression of Hnf4 from mice exposed to 3 weeks of UCMRS (Fig. 1A). Our results indicated that Hnf4 expression is significantly reduced in the intestines after stress exposure (Fig. 3I–J). In addition, leucine rich repeat containing G protein coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5), which is known to be suppressed in Hnf4 knockout animals, was also significantly reduced, demonstrating successful Hnf4 deletion (Supplementary Fig. 3D) (Chen et al., 2020). Further supporting our data, germ-free mice that had been given fecal pellets from stressed or naïve mice showed no differences in Hnf4 expression, suggesting that Hnf4 expression changes are not driven by transferrable microbial products from stressed or naïve mice (Supplementary Fig. 3E–F).

Fig. 3.

HNF4 regulates expression of Muc13: (A) HNF4 and H3K27ac ChIP-Seq of wildtype duodenal tissue at the Muc13 promoter. (B) RNA Polymerase II ChIP-Seq in duodenal villus tissue in control and Hnf4 DKO animals at the Muc13 promoter. (C) H3K4me3 HiChIP-Seq examining chromatin loops in control and Hnf4 DKO duodenal villus tissue at the Muc13 promoter. (D) Muc13 RNA-Seq fragments per kilobase per million in control and Hnf4 DKO duodenal tissue (two-tailed unpaired t- test). All sequencing experiments performed on 3 mice/group. Male and female mice. Relative quantity of (E) Hnf4α, (F) Hnf4γ, and (G) Muc13, across the intestines in control and Hnf4 DKO animals. Female mice, 5 mice/group. Two-way ANOVA. (H) Fold changes of mucins in the intestines of Hnf4 DKO and control animals by mass spectrometry. All sections of the intestines are pooled for a total of 12 samples from 3 mice per group. Female mice. Relative quantities of (I) Hnf4α and (J) Hnf4γ across the intestines in naïve and stress animals. Male mice, 11–12 mice per group; Two-way ANOVA.

To confirm our results in vitro and examine the impacts of HNF4 on Muc13 expression more directly, we utilized HT-29 cells. HT-29 cells are a human colon cancer cell line that is known to express both mucins and Hnf4 (Darsigny et al., 2010; Gupta et al., 2014). Cells were treated with an HNF4 antagonist (BI6015) or a DMSO control for 24 h (Kiselyuk et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2022). We then extracted the RNA from the collected cells and examined mucin expression as before. We found that treatment with the antagonist BI6015 showed a significant downregulation of MUC13 expression (Supplementary Fig. 3G). In addition, LGR5 showed decreased expression with BI6015, demonstrating successful antagonist activity on HNF4 (Supplementary Fig. 3H) (Gupta et al., 2014). These results further support the hypothesis that MUC13 is regulated by HNF4.

Together, our data suggest that in the absence of HNF4, there is less active transcription at, and fewer transcripts of, the Muc13 gene. In addition, loss of Hnf4 significantly reduces MUC13 protein expression across the intestines. These data support the hypothesis that Muc13 expression is regulated by HNF4. Our results also demonstrate that after UCMRS exposure, there is a significant reduction in Hnf4 that occurs independently of transferrable microbial products, suggesting that stress can reduce Hnf4 in vivo. Finally, we show that direct modulation of HNF4 results in Muc13 expression changes in vitro, validating our in vivo findings. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Muc13 expression is modulated by HNF4 in vitro, in vivo, and after stress exposure.

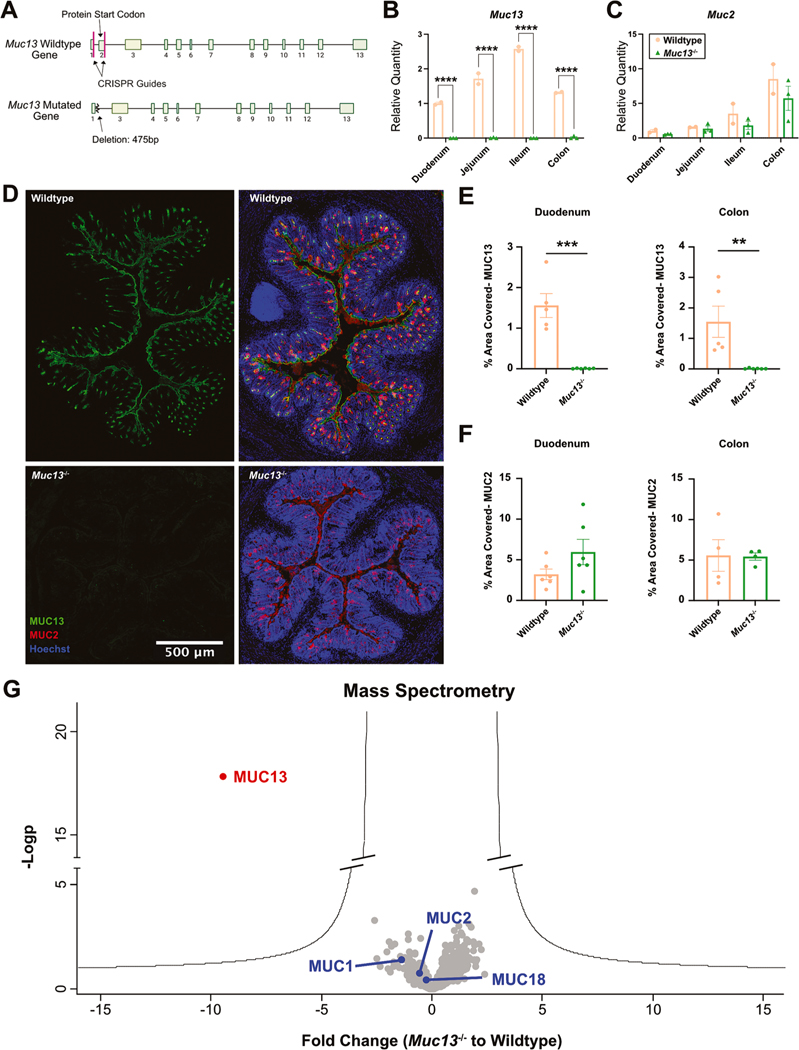

3.5. Muc13 deletion induces baseline behavioral and microbiome changes and renders mice more susceptible to UCMRS

Given our data demonstrating that Muc13 is specifically downregulated in stressed animals (Fig. 2B), we sought to examine if deleting Muc13 impacted the microbiome and behavioral outputs in mice. Using the i-GONAD system, we created a Muc13 knockout (Muc13−/− ) mouse line by deleting a 475 bp region of the Muc13 gene containing the start codon (Fig. 4A) (Gurumurthy et al., 2019; Ohtsuka et al., 2018). Validation of the knockout line was performed using both qPCR (Fig. 4B–C) and immunofluorescence (Fig. 4D–E). Importantly, no changes were observed in Muc2 at the transcript or protein levels, suggesting that Muc2 expression was not changed with the loss of Muc13 (Fig. 4C and F). To complement this approach, and given the dramatic reduction in mucin 13 transcript, we also examined detectable mucins at the protein level by mass spectrometry in Muc13−/− and control animals. We found a significant reduction in MUC13 protein abundance in all sections of the intestine (Fig. 4G). No other detectable mucin was statistically significantly changed (Fold Change > 5), suggesting that none of the other membrane mucins nor soluble mucins, compensate for the loss of MUC13. In addition, to confirm no changes in barrier integrity, we examined expression of tight junction proteins in our Muc13−/− animals. No changes in tight junction RNA expression were observed (Supplementary Fig. 4A–B). Together, these data demonstrate a successful deletion of mucin 13 in our knockout line.

Fig. 4.

Muc13 deletion validation: (A) Muc13 deletion schematic. Relative quantities of (B) Muc13 and (C) Muc2 in wildtype and Muc13−/− mice. Male mice, n = 2–3 per group, N = 1. T-tests, two-tailed. (D) Representative images of immunofluorescence (IF) staining of MUC13, MUC2 and Hoechst in the colon of wildtype and Muc13−/− animals. Quantification of IF of (E) MUC13 and (F) MUC2 in the duodenum and colon of wildtype and Muc13−/− mice. Male mice. T-tests, n = 4–6 per group, N = 2. (G) Fold change of mucins in the intestines of Muc13−/− compared to wildtype controls by mass spectrometry. All sections of the intestines are pooled for a total of 12 samples from 3 mice per group. Male mice.

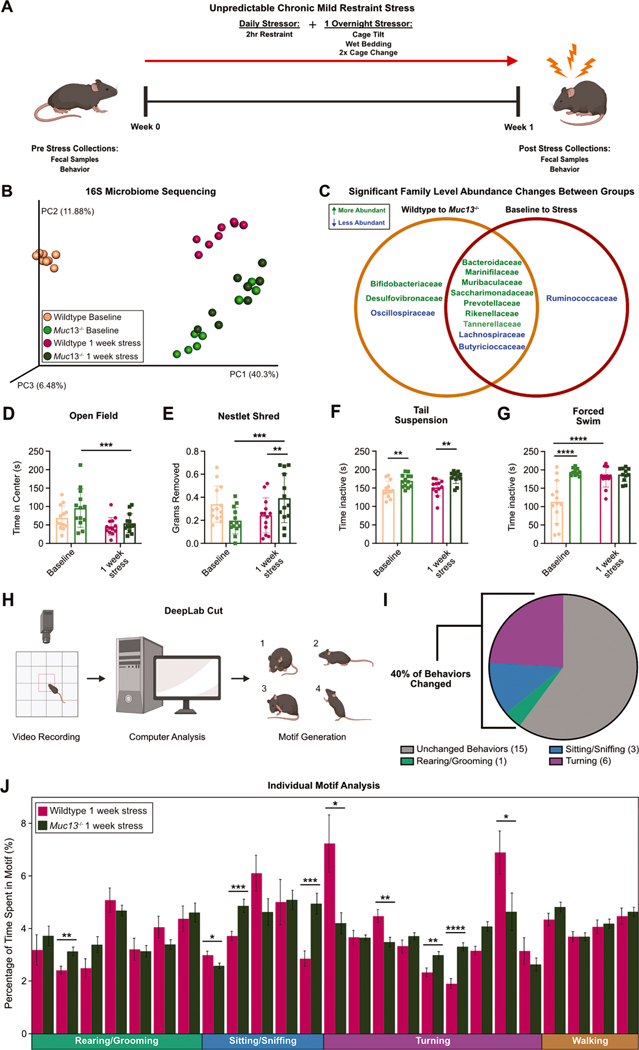

We next sought to understand the impacts of Muc13 deletion on microbiome composition. We compared 16S sequencing results from fecal samples collected from adult wildtype and Muc13−/− animals that were separated by genotype at weaning. Interestingly, we found that Muc13−/− animals (light green) clustered distinctly from wildtype controls (light orange), suggesting that Muc13 deletion significantly impacts the composition of the microbiome at baseline (Fig. 5B). In addition, to understand if Muc13−/− animals have stress-induced microbiome shifts, we used an abbreviated 1-week UCMRS protocol (Fig. 5A). In our hands, this abbreviated protocol allows for substantial microbial shifts, but does not yet yield all stress-induced anxiety-like and despair behaviors in wildtype animals (Fig. 5D–G, light orange to dark pink bars). This allowed us to examine if Muc13−/− mice are more susceptible to UCMRS-induced behavioral changes than their Muc13 competent controls. As animals that are more susceptible to UCMRS-induced behavioral changes would be expected to show behavioral changes sooner than wildtype animals, our 1 week UCMRS protocol allowed us to examine behavior differences at an earlier timepoint. Our results show that while wildtype samples display a significant shift in microbial composition after 1 week of UCMRS (light orange to dark pink dots), Muc13−/− (light green to dark green dots) samples remained clustered together (Fig. 5B). This suggests that the microbiome of Muc13−/− animals is different from widltype animals at baseline and is less modified by 1-week of UCMRS exposure. In addition, samples from wildtype animals exposed to 1 week of UCMRS shifted towards both Muc13−/− groups (baseline and 1 week UCMRS, light and dark green dots), supporting the idea the Muc13−/− animals have baseline microbial signatures which resemble stress-induced microbiome changes (Fig. 5B). To further understand the similarities between the Muc13−/− microbiome and the UCMRS-exposed microbiome, we compared the significantly changed bacterial families between baseline wildtype and baseline Muc13−/− animals to the significantly changed bacterial families between baseline wildtype animals and wildtype animals exposed to 1 week of UCMRS. Of the bacterial families that had significant changes in either group, 69% of those changes overlapped (Fig. 5C). While we also examined overlapping changes at the genus and ASV levels, algorithm matching limitations hindered our ability to draw conclusions. While 58% of genera and 62% of ASV changes overlapped between groups, only ~45% of total reads could be matched to a known genus or ASV – making clear comparisons at these levels difficult (Extended Data Table 3). Nonetheless, data at the family level suggests significant overlap in changes between baseline control and baseline Muc13−/− animals when compared to baseline wildtype and UCMRS exposed wildtype animals. This suggests that the overlapping changes between baseline wildtype and UCMRS exposed wildtype animals and wildtype to Muc13−/− animals may be driven by reductions in Muc13. Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that reductions in Muc13 drive microbiome changes.

Fig. 5.

Microbiome and behavioral changes in Muc13−/− mice at baseline and after stress exposure: (A) Experimental design. (B) PCoA plot of 16S fecal microbial sequencing in wildtype and Muc13−/− animals at baseline and after 1 week of stress exposure. Male mice, n = 8 per group, N = 1. (C) Venn diagram comparing significantly changed families from 16S fecal microbiome sequencing between wildtype and Muc13−/− animals to families changed between wildtype baseline and stress exposed animals. (D) Open field and (E) nestlet shredding tests comparing anxiety-like behaviors between wildtype and Muc13−/− animals at baseline and after 1 week of stress exposure. (F) Tail suspension and (G) forced swim tests between wildtype and Muc13−/− animals at baseline and after 1 week of stress exposure. Male mice, Two-way ANOVA, n = 13 per group, N = 2. (H) DeepLabCut experimental design. (I) Pie chart of quantified behavioral motifs changed between wildtype and Muc13−/− animals. (J) Individual motif analysis after 1 week of stress exposure between wildtype and Muc13−/− animals. Two-tailed T-tests, male and female mice, n = 13–24 per group, N = 3.

Given the established connection between microbiome changes and mental health, we sought to examine if Muc13 deletion impacted anxiety-like and despair behaviors in mice (Marin et al., 2017). Both Muc13−/− animals and wildtype controls were subjected to the open field, nestlet shred, tail suspension, and forced swim tests (Fig. 5A, D–G). Behavior was collected at baseline and after 1 week of UCMRS for all animals. Interestingly, at baseline, we observed no differences in anxiety-like behaviors in the open field or nestlet shredding tests between Muc13−/− and wildtype controls (Fig. 5D–E, left columns). However, strong despair behaviors were observed in both the tail suspension and forced swim tests (Fig. 5F–G, left columns), suggesting Muc13−/− mice display innate despair, but not anxiety-like, behaviors. In addition, to gain a full picture of the impact of Muc13 deletion on susceptibility to stress-induced despair and anxiety-like behaviors, we subjected wildtype and Muc13−/− mice to 1 week of UCMRS. As stated above, 1 week of UCMRS exposure represents a subclinical model of stress that does not induce all expected behavioral changes in wildtype animals (Peng et al., 2012; Pothion et al., 2004). Thus, we hypothesized that if Muc13−/− deletion rendered animals more susceptible to stress, they would exhibit despair and anxiety-like behaviors earlier than wildtype animals (Nollet et al., 2013). Supporting this hypothesis, following 1 week of UCMRS, Muc13−/− animals had significant reductions in the amount of time spent in the center of the open field test, as well as significant increases in the amount of nestlet removed in the nestlet shred test. Of note, no changes in distance traveled were observed between groups in the open field test at baseline or after 1 week of UCMRS (data not shown). These results indicate that 1 week of UCMRS is sufficient to increase anxiety-like phenotypes in Muc13−/− animals, but not their wildtype counterparts (Fig. 5D–E, green columns). Furthermore, in the tail suspension and forced swim tests, we saw no increase in time spent inactive as the Muc13−/− animals presented with despair behaviors at baseline and likely hit a ceiling effect (Fig. 5F–G, green columns). To complement these classical behavioral assays, we used unbiased artificial intelligence (DeepLabCut) to detect animal poses (Fig. 5H–J and Supplementary Fig. 5) (Mathis et al., 2018; Rivet-Noor et al., 2022). In this approach, 10-minute videos of mice exploring an open field box were broken down into 25 individual motifs (Fig. 5H). Each motif was characterized and grouped into a general behavioral classification (rearing/grooming, turning, etc.). Individual motifs represent a behavioral pattern based on mouse limb and tail position detected by DeepLabCut. For example, the general behavior classification “turning” included motifs such “head turning left”, “mid-point of right turn”, etc. As these motifs together make up a complete behavior, they were grouped in general behavioral classifications. Once grouped, changes in the percentage of time spent in each behavioral motif were quantified between Muc13−/− and wildtype animals (Fig. 5H–J). Baseline analysis revealed that of the 25 distinct motifs, 16% were significantly changed between groups (Supplementary Fig. 5A–B), suggesting that, like in classical behavioral assays, distinctions between Muc13−/− and wildtype animals are present at baseline. Similarly, the DeepLabCut software was able to detect significant differences between groups after 1 week of UCMRS exposure, with 40% of behavioral motifs being changed between Muc13−/− and wildtype controls (Fig. 5I–J).

Our results show that Muc13 deletion can drive both microbiome shifts that mirror microbial changes induced by stress, and despair behaviors at baseline – highlighting the critical role of mucin 13 in maintaining microbial and behavioral homeostasis. In addition, deletion of Muc13 increases stress-induced anxiety-like behaviors. Together, these results support the hypothesis that stress-induced Muc13 reductions can drive microbial shifts that lead to behavioral changes in mice.

4. Discussion

Our work demonstrates that stress-induced microbiome and behavioral changes are accompanied by a reduction in expression of a key component of the glycocalyx, mucin 13. While more work is needed to fully understand the mechanisms behind this reduced expression, our data suggest that the intestinal transcription factor HNF4 is a key mediator. Furthermore, we demonstrate for the first time that deletion of a glycocalyx protein is sufficient to drive microbiome shifts and behavioral changes, suggesting that transmembrane mucins have a larger role in microbiome homeostasis than previously acknowledged. In addition, this work provides the foundation for understanding a mechanism by which stress can alter the microbiome, providing a new therapeutic target that avoids current microbiome treatment pitfalls.

Our results, while novel, are supported by concepts previously published in literature. For example, it is well known that there is a reciprocal relationship between the mucus layer and microbes (Hansson, 2020). Disruption of the intestinal mucus layer results in sweeping microbiome changes, heightened inflammation, and disease onset–supporting the idea that changes in mucus can impact other systems in the body (Bergstrom et al., 2010, 2020; Borisova et al., 2020; Hansson, 2020; Johansson et al., 2008, 2009; Van der Sluis et al., 2006; Velcich et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2018). We take this concept a step further and demonstrate that changes in a glycocalyx mucin can shift the composition of microbes. Additionally, stress has been shown to alter the glycosylation patterns of soluble mucins (Silva et al., 2014). As changes in glycosylation are also known to alter the microbiome, the connection between stress and mucin induced microbiome changes is well supported (Marczynski et al., 2021; Werlang et al., 2019). Finally, the connection between mucins and depression has also been suggested in the literature. Specifically, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in MUC13 have been identified in GWAS studies of depressed populations (Dunn et al., 2018; Rivet-Noor and Gaultier, 2020; Ware et al., 2015). In addition, SNPs in O-glycosylation have also been identified in populations with treatment resistant depression (McClain et al., 2020; Rivet-Noor and Gaultier, 2020). In aggregate, these published concepts support our rational for performing these experiments and suggest that mucin 13 is an important driver of microbiome shifts and despair behaviors in mice.

The quantification and detection of mucins and their glycan chains has long proven to be a challenge for glycobiologists (Atanasova and Reznikov, 2019; Carraway, 2000; Harrop et al., 2012; Kesimer and Sheehan, 2012). Recent advances, including utilization of inactive mucin-specific proteases for mass spectrometry, has allowed researchers to begin to interrogate many previously unanswered questions about these glycan rich proteins (Harrop et al., 2012; Kesimer and Sheehan, 2012; Malaker et al., 2019, 2022). However, even with these cutting edge techniques, limitations remain. While mass spectrometry is among the most successful methods of mucin detection, we were unable to capture subtle differences in mucin expression at the protein level. In addition, while able to detect several mucins in our samples, we remained unable to identify other members of the intestinal transmembrane mucin family, namely mucin 17. This is likely due to the heavy ratio of glycans. Immunofluorescent staining of mucins can be employed to great success when examining where specific mucins are located and their turnover times (Henwood, 2017; Schneider et al., 2018). However, quantifying mucins, especially subtle changes, with this technique remains challenging as intestinal villi often shift in and out of imaging fields, making quantification along a villus or detection of changes in fluorescence across the intestine difficult to assess. Furthermore, preservation of mucus and mucins can be inconsistent across intestinal sections due to fecal accumulation and physical manipulation, even while using identical methods. This limitation precludes confident protein level quantification of identical areas across samples. Western blotting and ELISA detection of mucins can be utilized in some cases, however, the isolation of mucins remains a large technical hurdle (Atanasova and Reznikov, 2019). Together, these limitations explain why RNA quantification of mucins remains a reliable method for examining differences in mucin expression. Future studies with more sensitive and replicable methods for mucin quantification at the protein level will need to be performed to confirm our stress-induced mucin expression results.

Mechanistically, our results show that HNF4 can bind to the Muc13 promoter, while the loss of Hnf4 results in reduced transcription of Muc13 in the intestines of mice. In addition, we have shown that chronic stress induces reductions in both Muc13 and Hnf4 expression. While more work is needed to understand how stress regulates Hnf4 in our chronic stress model, literature suggests that this regulation could occur through the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2. While there is no glucocorticoid response element (GRE) in the Hnf4 gene, ERK 1/2 is known to be a potent inhibitor of Hnf4 expression (Vető et al., 2017). Strikingly, stress hormones have repeatedly been demonstrated to enhance ERK 1/2 phosphorylation (Gourley et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2010). These works provide a mechanistic foundation for how stress could be reducing Hnf4 expression in the intestines. While the basis for our hypothesis is well supported, no works have demonstrated how stress specifically regulates Hnf4, leaving a gap in knowledge to be filled by future studies.

By defining a novel mechanism through which stress alters the microbiome, our results have brought to light a key aspect in stress-induced behavioral changes. We have demonstrated that a transmembrane mucin is specifically and indirectly regulated by stress in a way that interferes with its homeostatic expression patterns, inducing microbiome composition changes and despair behaviors in mice. Mucin 13 is conserved between humans and mice, suggesting it could be a broadly applicable therapeutic target for patients with stress-induced depression who present with microbiome changes. Our results, while directly related to stress-induced depression, provide a basis for further research to target transmembrane mucins as intervention points for diseases that present with, or are driven by, pathogenic microbiome alterations, such as colitis or Parkinson’s Disease (Herath et al., 2020).

Extended Data

Extended Data Table 1.

Table of naïve vs stress genus level Wilcox Rank Sum statistics (for Supplemental Fig. 1J).

| Naïve vs Stress | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | p value | Bonferroni-adjusted p value | Star |

| Clostridium sensu stricto 1 | 7.99E-09 | 4.87E-07 | **** |

| Romboutsia | 1.47E-07 | 8.94E-06 | **** |

| [Eubacterium] ventriosum group | 1.68E-07 | 1.02E-05 | **** |

| Lachnospiraceae UCG-001 | 9.83E-07 | 6.00E-05 | **** |

| Marvinbryantia | 1.94E-06 | 0.000118164 | **** |

| Staphylococcus | 3.79E-06 | 0.000231457 | **** |

| Lachnospiraceae FCS020 group | 6.88E-06 | 0.000419638 | *** |

| Unidentified | 1.57E-05 | 0.000956612 | *** |

| [Eubacterium] nodatum group | 1.97E-05 | 0.00119998 | ** |

| Incertae Sedis | 1.97E-05 | 0.00119998 | ** |

| [Eubacterium] siraeum group | 3.60E-05 | 0.002198371 | ** |

| [Eubacterium] brachy group | 4.23E-05 | 0.002577603 | ** |

| Lactobacillus | 6.60E-05 | 0.004024766 | ** |

| Family XIII AD3011 group | 6.66E-05 | 0.004060181 | ** |

| Anaeroplasma | 7.81E-05 | 0.004765721 | ** |

| Tuzzerella | 9.25E-05 | 0.005640638 | ** |

| Oscillospira | 0.000339724 | 0.020723155 | * |

| NK4A214 group | 0.00037941 | 0.023144017 | * |

| GCA-900066575 | 0.00039326 | 0.023988861 | * |

| Anaerotruncus | 0.000551996 | 0.03367175 | * |

| Harryflintia | 0.00367754 | 0.224329947 | |

| ASF356 | 0.004282089 | 0.261207403 | |

| Roseburia | 0.004291511 | 0.261782185 | |

| Tyzzerella | 0.008777645 | 0.535436319 | |

| Lachnospiraceae UCG-010 | 0.013523212 | 0.82491592 | |

| [Eubacterium] oxidoreducens group | 0.589533221 | 1 | |

| [Eubacterium] xylanophilum group | 0.147193088 | 1 | |

| A2 | 0.130510373 | 1 | |

| Acetatifactor | 0.584766531 | 1 | |

| Akkermansia | 0.057741754 | 1 | |

| Arsenicicoccus | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| Bacillus | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| Burkholderia-Caballeronia-Paraburkholderia | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| Butyricicoccus | 0.06679277 | 1 | |

| Colidextribacter | 0.147193088 | 1 | |

| Corynebacterium | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| Curtobacterium | 1 | 1 | |

| Desulfovibrio | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| Enterococcus | 0.678841491 | 1 | |

| Enterorhabdus | 0.020288409 | 1 | |

| Erysipelatoclostridium | 0.072758087 | 1 | |

| Exiguobacterium | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| HT002 | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| Intestinimonas | 0.017242287 | 1 | |

| Lachnoclostridium | 0.814269221 | 1 | |

| Lachnospiraceae NC2004 group | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group | 0.351411522 | 1 | |

| Lachnospiraceae NK4B4 group | 0.133661781 | 1 | |

| Lachnospiraceae UCG-004 | 0.147774975 | 1 | |

| Lachnospiraceae UCG-006 | 0.630998004 | 1 | |

| Monoglobus | 0.630998004 | 1 | |

| Nocardiopsis | 0.161691678 | 1 | |

| Ornithinimicrobium | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| Oscillibacter | 0.033682558 | 1 | |

| Parvibacter | 0.046071649 | 1 | |

| Ralstonia | 0.161691678 | 1 | |

| Ruminococcus | 0.395580536 | 1 | |

| Sanguibacter-Flavimobilis | 0.3378947 | 1 | |

| Turicibacter | 0.327313318 | 1 | |

| UCG-005 | 0.017069953 | 1 | |

| UCG-009 | 0.675265662 | 1 | |

Extended Data Table 2.

Table of statistics for genus level changes between baseline control, baseline Muc13−/−, 1wk UCMRS control, 1wk UCMRS Muc13−/− animals.

| Baseline Control vs. Muc13 KO- 33.4% coverage | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | tstat | p_val | p_adj |

| Alistipes | −5.906873503 | 0.000595337 | 0.012943066 |

| Bacteroides | −5.607695288 | 0.000809375 | 0.012943066 |

| Odoribacter | −5.588133367 | 0.000826153 | 0.012943066 |

| Muribaculum | −4.763260118 | 0.002051689 | 0.022701292 |

| Prevotellaceae UCG-001 | −4.623889432 | 0.002415031 | 0.022701292 |

| Intestinimonas | 3.894457548 | 0.00300306 | 0.023523973 |

| Bifidobacterium | −3.921415122 | 0.005738596 | 0.038530574 |

| Oscillibacter | 3.264826755 | 0.010629363 | 0.062447507 |

| Lachnoclostridium | 3.167010682 | 0.015031735 | 0.070649153 |

| Ruminococcus | 2.828785268 | 0.013738733 | 0.070649153 |

| Ligilactobacillus | −3.132610491 | 0.016549203 | 0.070710232 |

| Alloprevotella | −2.878795057 | 0.023692332 | 0.085656894 |

| Roseburia | −2.890222916 | 0.023308834 | 0.085656894 |

| A2 | 2.503323677 | 0.02838 | 0.095275714 |

| Candidatus Saccharimonas | −2.69615309 | 0.030810076 | 0.096538238 |

| Wildtype Baseline vs 1wk UCMRS- 26.4% coverage | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | tstat | p_val | p_adj |

| Alistipes | −9.135862606 | 3.87E-05 | 0.000870574 |

| Prevotellaceae UCG-001 | −9.609585728 | 2.78E-05 | 0.000870574 |

| Bacteroides | −6.418234757 | 0.000360945 | 0.005414182 |

| Odoribacter | −6.116007048 | 0.000483403 | 0.005438285 |

| Ruminococcus | 3.89327961 | 0.002875679 | 0.025881113 |

| Alloprevotella | −4.098199411 | 0.00458341 | 0.034375578 |

| Lachnoclostridium | 3.332877095 | 0.012541499 | 0.080623924 |

| Muribaculum | −3.226870145 | 0.014514543 | 0.081644302 |

| [Eubacterium] xylanophilum group | 2.696965122 | 0.020343235 | 0.098082324 |

| Ligilactobacillus | −2.937322606 | 0.021796072 | 0.098082324 |

| Intestinimonas | 2.466953441 | 0.027653502 | 0.113127965 |

| Parabacteroides | −2.615690041 | 0.034625544 | 0.129845792 |

Extended Data Table 3.

Table of statistics for ASV level changes between baseline control, baseline Muc13−/−, 1wk UCMRS control, 1wk UCMRS Muc13−/− animals.

| Baseline Control vs. Muc13 KO- 56.7% coverage | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ASV | tstat | p_val | p_adj |

| ASV261 | 13.55474313 | 4.38E-08 | 3.91E-05 |

| ASV508 | 18.35322467 | 5.48E-08 | 3.91E-05 |

| ASV309 | 20.8989131 | 1.44E-07 | 6.86E-05 |

| ASV252 | 10.30073205 | 2.46E-07 | 8.76E-05 |

| ASV579 | 18.14495266 | 3.82E-07 | 0.000108944 |

| ASV658 | 8.886294194 | 6.87E-07 | 0.000163375 |

| ASV209 | 10.56315343 | 2.92E-06 | 0.000462696 |

| ASV221 | 12.23303713 | 2.43E-06 | 0.000462696 |

| ASV375 | 8.709734713 | 2.74E-06 | 0.000462696 |

| ASV157 | 11.86206446 | 4.02E-06 | 0.000573785 |

| ASV139 | −12.22784171 | 5.60E-06 | 0.000580085 |

| ASV479 | 9.711390083 | 5.70E-06 | 0.000580085 |

| ASV499 | 12.05471762 | 4.67E-06 | 0.000580085 |

| ASV507 | 9.274542305 | 5.50E-06 | 0.000580085 |

| ASV17 | −11.80225232 | 7.11E-06 | 0.000626425 |

| ASV259 | −11.71552992 | 7.47E-06 | 0.000626425 |

| ASV723 | 11.89549577 | 6.74E-06 | 0.000626425 |

| ASV210 | 9.685252445 | 1.16E-05 | 0.000754124 |

| ASV212 | 9.133909209 | 1.07E-05 | 0.000754124 |

| ASV543 | 10.26401728 | 1.03E-05 | 0.000754124 |

| ASV6 | −10.9756093 | 1.15E-05 | 0.000754124 |

| ASV810 | 9.969756019 | 1.07E-05 | 0.000754124 |

| ASV170 | 10.54225436 | 1.51E-05 | 0.000935521 |

| ASV540 | 9.790630844 | 1.64E-05 | 0.000976801 |

| ASV537 | 10.16091857 | 1.85E-05 | 0.00105454 |

| ASV703 | 10.12336975 | 1.97E-05 | 0.001082212 |

| ASV240 | −9.8230063 | 2.41E-05 | 0.001165969 |

| ASV67 | −9.745713299 | 2.53E-05 | 0.001165969 |

| ASV690 | 9.663420615 | 2.28E-05 | 0.001165969 |

| ASV799 | 9.766995866 | 2.50E-05 | 0.001165969 |

| ASV809 | 8.070231752 | 2.37E-05 | 0.001165969 |

| ASV149 | 9.139513451 | 2.78E-05 | 0.001219691 |

| ASV450 | 8.939979187 | 2.83E-05 | 0.001219691 |

| ASV581 | 8.569228461 | 2.91E-05 | 0.001219691 |

| ASV16 | −9.119727895 | 3.91E-05 | 0.001559557 |

| ASV272 | 8.554968202 | 4.24E-05 | 0.001559557 |

| ASV462 | 8.807212142 | 4.27E-05 | 0.001559557 |

| ASV608 | 9.07368902 | 4.05E-05 | 0.001559557 |

| ASV672 | 9.030297271 | 4.17E-05 | 0.001559557 |

| ASV199 | 8.933250548 | 4.48E-05 | 0.001596125 |

| ASV55 | −8.898985274 | 4.59E-05 | 0.001596557 |

| ASV568 | 8.231115378 | 5.12E-05 | 0.001739587 |

| ASV12 | −8.599851126 | 5.73E-05 | 0.001894653 |

| ASV166 | 8.262399644 | 5.85E-05 | 0.001894653 |

| ASV341 | −8.514751246 | 6.11E-05 | 0.001935655 |

| ASV233 | −8.414312687 | 6.59E-05 | 0.002003358 |

| ASV695 | 8.412500859 | 6.60E-05 | 0.002003358 |

| ASV191 | 7.899890992 | 8.30E-05 | 0.002365922 |

| ASV585 | 8.142565289 | 8.14E-05 | 0.002365922 |

| ASV776 | 7.238906207 | 8.26E-05 | 0.002365922 |

| ASV841 | 7.663499042 | 9.13E-05 | 0.002552304 |

| ASV38 | −7.920130544 | 9.72E-05 | 0.002623258 |

| ASV381 | −7.915999155 | 9.75E-05 | 0.002623258 |

| ASV356 | −7.882119892 | 0.000100199 | 0.002646003 |

| ASV344 | −7.781088935 | 0.000108769 | 0.002732749 |

| ASV582 | 7.721589103 | 0.000108645 | 0.002732749 |

| ASV766 | 6.967111759 | 0.000109233 | 0.002732749 |

| ASV481 | 7.594850443 | 0.000126824 | 0.003106634 |

| ASV525 | 7.526268861 | 0.000128535 | 0.003106634 |

| ASV29 | −7.525171194 | 0.000134431 | 0.003194968 |

| ASV138 | 7.415407048 | 0.000139897 | 0.003217687 |

| ASV574 | 6.852858701 | 0.000139899 | 0.003217687 |

| ASV225 | 7.404122877 | 0.0001489 | 0.003370339 |

| ASV625 | 6.840196243 | 0.000176735 | 0.0038959 |

| ASV713 | 7.199177191 | 0.000177583 | 0.0038959 |

| ASV607 | 7.014797005 | 0.000208794 | 0.00451121 |

| ASV70 | −6.969364349 | 0.000217403 | 0.004627117 |

| ASV623 | 6.879783804 | 0.000235574 | 0.004940135 |

| ASV19 | −6.844143848 | 0.000243274 | 0.005027668 |

| ASV239 | −6.773745545 | 0.00025933 | 0.0052161 |

| ASV440 | −6.772147445 | 0.000259708 | 0.0052161 |

| ASV411 | −6.67747883 | 0.000283248 | 0.00560989 |

| ASV306 | −6.598698476 | 0.000304675 | 0.005871173 |

| ASV314 | −6.609031063 | 0.000301764 | 0.005871173 |

| ASV59 | −6.462062044 | 0.000346297 | 0.006584259 |

| ASV198 | 6.305065991 | 0.000399351 | 0.007493078 |

| ASV10 | −6.282502554 | 0.000411037 | 0.007514601 |