Abstract

Purpose

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) remains a devastating complication of pancreatoduodenectomy (PD). Minimally invasive PD (MIPD), including laparoscopic (LPD) and robotic (RPD) approaches, have comparable POPF rates to open PD (OPD). However, we hypothesize that the likelihood of having a more severe POPF, as defined as clinically relevant POPF (CR-POPF), would be higher in an MIPD relative to OPD.

Methods

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) targeted pancreatectomy dataset (2014–2020) was reviewed for any POPF after OPD. Propensity score matching (PSM) compared MIPD to OPD, and then RPD to LPD.

Results

Among 3,083 patients who developed a POPF, 2,843 (92.2%) underwent OPD and 240 (7.8%) MIPD; of these, 25.0% were LPD (n = 60) and 75.0% RPD (n = 180). Grade B POPF was observed in 45.4% (n = 1,400), and grade C in 6.0% (n = 185). After PSM, MIPD patients had higher rates of CR-POPF (47.3% OPD vs. 54.4% MIPD, p = 0.037), as well as higher reoperation (9.1% vs. 15.3%, p = 0.006), delayed gastric emptying (29.2% vs. 35.8%, p = 0.041), and readmission rates (28.2% vs. 35.1%, p = 0.032). However, CR-POPF rates were comparable between LPD and RPD (56.8% vs. 49.3%, p = 0.408).

Conclusion

The impact of POPF is more clinically pronounced after MIPD than OPD with a more complex postoperative course. The difference appears to be attributed to the minimally invasive environment itself as no difference was noted between LPD and RPD. A clear biological explanation of this clinical observation remains missing. Further studies are warranted.

Keywords: Pancreatoduodenectomy, Minimally invasive surgery, Pancreas, Pancreatic neoplasms, Postoperative complications

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is indicated for management of a variety of benign and malignant conditions, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Despite significant improvements in perioperative care, PD remains associated with considerable morbidity and mortality [1–3]. Minimally invasive surgery has revolutionized management of numerous gastrointestinal disorders and its benefits are well established [4]. Aiming to lessen the physiologic impact and to improve upon outcomes of an open PD (OPD), minimally invasive PD (MIPD) emerged as an alternative as well. MIPD includes both laparoscopic (LPD) and robotic (RPD) approaches and has been steadily increasing in acceptance—in 2010 to 2011, 14% of all PD cases in the United States were performed minimally invasively [5–8].

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is the most consequential complication of PD and is estimated to occur in 5% to 30% of patients [1,2]. POPF may give rise to a number of life-threatening sequelae including postpancreatectomy hemorrhage and sepsis [9–11]. In 2016, the International Study Group for Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) refined POPF definitions to distinguish clinically occult biochemical leaks (previously called grade A POPF) from clinically relevant POPF (CR-POPF) that alter the expected postoperative course [10,11]. The effect of surgical approach on POPF has been examined extensively in the literature with conflicting results. A recent meta-analysis of LPD trials found no significant difference in overall POPF rates when compared to OPD, although biochemical leaks were included [12–14]. Conversely, retrospective reports note lower rates of CR-POPF with RPD suggesting a modest advantage over OPD [3,4,15–17].

However, concerns of more clinically significant POPF after MIPD than OPD persist. We hypothesize that if POPF occurs following a PD, the likelihood of having a CR-POPF would be higher in an unconverted MIPD versus OPD. In this study, we sought to examine rates of CR-POPF formation among patients undergoing OPD or MIPD who develop any grade POPF and to compare differences between RPD and LPD approaches in a multi-institutional national database.

METHODS

Data acquisition and patient selection

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP-NSQIP) targeted pancreatectomy dataset between 2014 and 2020 was reviewed. ACS NSQIP NSQIP is a standardized, validated, and prospectively maintained multi-institutional national repository of participating hospitals mostly in the United States. There are currently over 800 listed hospitals which range from community to academic institutions [18,19]. The targeted pancreatectomy PUF (participant user file) includes variables specific to pancreatectomy procedures, such as delayed gastric emptying (DGE) and POPF. Case ID numbers were used to match ACS NSQIP and targeted pancreatectomy ACS NSQIP databases.

Patients aged >18 years undergoing PD for any indication were identified using CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) codes 48150, 48152, 48153, and 48154. Cases were screened for procedural, clinical, technical, and outcome variables. Patients meeting the following exclusion criteria were not included in the analysis: metastatic disease, ascites, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scores >1, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class V, emergent or urgent cases, concomitant vascular or visceral resection at time of resection, concurrent other pancreatic operations, unknown or unclear surgical approach (including hybrid laparoscopic, robotic, and open cases), and cases with missing details on type of pancreatic reconstruction.

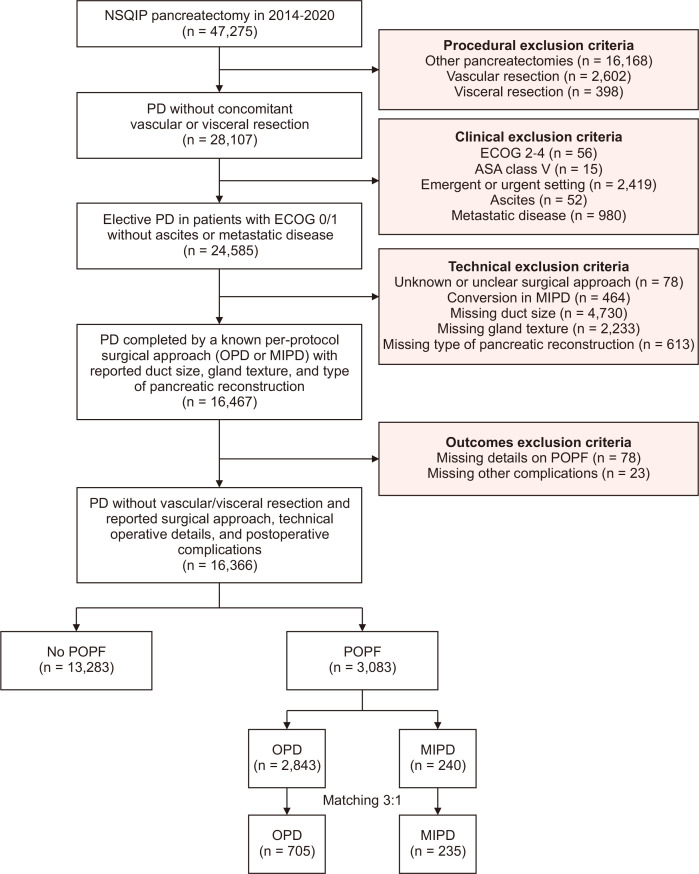

The fistula risk score (FRS) was developed to predict the risk of POPF development based on gland texture, pancreatic duct diameter, pathology, and intraoperative blood loss [20,21], then modified to include sex, body mass index (BMI), preoperative bilirubin in addition to gland texture and pancreatic duct diameter using the NSQIP database [22]. Thus, those with missing data components of the FRS (duct size and gland texture) [21] and missing data or lacking details on POPF occurrence or severity were also excluded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram demonstrating the steps of patient selection and the final study design with subgroup matching. NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; PD, pancreatoduodenectomy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; OPD, open pancreatoduodenectomy; MIPD, minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy; POPF, postoperative pancreatic fistula.

The study was designed to evaluate how operative approaches are associated with the clinical significance of POPF in a per-protocol manner, and, therefore, MIPD cases that underwent conversion to OPD were not included in the analysis.

Study variables and outcomes

POPF occurrence in NSQIP is consistent with original ISGPF definitions. Specifically, patients were categorized as having a grade A POPF if drain amylase content exceeded three times institutional serum amylase activity on or after the third postoperative day in addition to either drain persistence for more than seven days, percutaneous drain placement, or reoperation. Moreover, the POPF definition was met if a clinical diagnosis was determined by an attending surgeon, in the case of drain persistence for more than 7 days, spontaneous wound drainage, percutaneous drain placement, or if oral intake was interrupted and parenteral nutrition initiated [9,23]. CR-POPF is defined in NSQIP as the presence of POPF as well as a change in anticipated postoperative course and includes grades B and C POPF. Specifically, grade B POPF required persistent peripancreatic drainage for more than 3 weeks, percutaneous or endoscopic drainage of POPF-associated collections, associated infections and angiographic procedures for POPF-associated bleeding. On the other hand, the grade C POPF definition was met when the above criteria were fulfilled and reoperation, organ failure, or death occurred [2].

Variables analyzed included patient-level characteristics such as age, sex, race, BMI, comorbidities, and risk factors. Data on operative indication, receipt of neoadjuvant therapy, reconstruction techniques, presence of preoperative biliary stents, and placement of postoperative drains were also studied. Lastly, other relevant outcomes examined included DGE, anemia requiring transfusion, hospital length of stay (LOS), and 30-day readmission.

Statistical analysis

Multivariable logistic regression models were generated to analyze CR-POPF occurrence and morbidity in patients reported as adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the entire cohort. Matching was then performed based on a multivariable logistic regression model for the likelihood of receiving OPD versus MIPD in the selected population to adjust for any inherent selection bias. Patients were matched by the OPD or MIPD approach, followed by subgroup analysis on the RPD versus LPD approach, based on preoperative, intraoperative, and pathologic variables. Preoperative variables included age, sex, BMI, race, ASA class and comorbidities, smoking, steroid use, weight loss, baseline laboratory results, jaundice, biliary stent placement, and receipt of neoadjuvant radiation. Intraoperative variables included reconstruction, colonic orientation, gland texture, duct size, vascular resection, and drain placement. Matching was performed using a 3:1 nearest neighbor approach for OPD versus MIPD and 1:2 for RPD versus LPD (due to available sample size) with a caliper width equal to 0.1 standard deviations. After matching was completed, calibration between the matched groups was assessed by testing p-values with a conditional logistic regression for categorical variables and mixed effect modeling for continuous variables. Balance was also assessed between groups before and after matching using standardized differences with values <10% for a given variable denoting relatively small imbalance.

Baseline characteristics were compared using logistic regression for matched and unmatched cohorts to assess for adequate balance after matching. Conditional logistic regression was used to compare categorical variables and mixed effect modeling for continuous variables. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp.) with R package version 3.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) for propensity score matching.

RESULTS

Demographic, clinical, and perioperative characteristics

The results of the univariable and multivariable regression analyses for predictors of clinically relevant POPF among patients who had POPF following their pancreatoduodenectomy are avaliable in Supplementary Table 1. After application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 16,366 patients remained, of which 3,083 (18.8%) developed a POPF and 13,283 (81.2%) did not (Fig. 1). Among the patients with development of POPF, 2,843 (92.2%) underwent OPD and 240 (7.8%) MIPD. Of those who underwent MIPD, 180 (75.0%) patients underwent RPD and 60 (25.0%) LPD. For the entire cohort, mean age was 64 years, and a majority were males (58.0%, n = 1,788) and White (75.5%, n = 2,327). Most PDs were performed for malignancy (68.1%, n = 2,101) and 376 patients (12.2%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). In the included cohort, 48.6% of POPF were classified as grade A (n = 1,498), whereas 45.4% (n = 1,400) were grade B, and 6.0% (n = 185) were grade C. Demographic and clinicopathologic information are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and perioperative characteristics of the selected patient population

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 3,083 |

| Age (yr) | 64.4 ± 12.0 (66) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1,788 (58.0) |

| Female | 1,295 (42.0) |

| Race | |

| White | 2,327 (75.5) |

| Black | 187 (6.1) |

| Others | 569 (18.5) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.7 ± 6.5 (28.0) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 1,671 (54.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 610 (19.8) |

| COPD | 141 (4.6) |

| CHF | 10 (0.3) |

| ESRD | 7 (0.2) |

| Risk factor | |

| Smoking | 458 (14.9) |

| Steroids | 104 (3.4) |

| Weight loss | 288 (9.3) |

| Bleeding disorder | 61 (2.0) |

| Preoperative anemia | 9 (0.3) |

| Indication | |

| Malignancy | 2,101 (68.1) |

| Benign | 965 (31.3) |

| Unknown | 17 (0.6) |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 376 (12.2) |

| Neoadjuvant radiation | 106 (3.4) |

| Approach | |

| Open | 2,843 (92.2) |

| Laparoscopic | 60 (1.9) |

| Robotic | 180 (5.8) |

| Biliary stent | |

| No | 1,632 (52.9) |

| Yes | 1,451 (47.1) |

| Duct size (mm) | |

| <3 | 1,432 (46.4) |

| 3–6 | 1,429 (46.4) |

| >6 | 222 (7.2) |

| Texture | |

| Soft | 2,243 (72.8) |

| Intermediate | 285 (9.2) |

| Hard | 555 (18.0) |

| Reconstruction | |

| PJ duct-to-mucosa | 2,715 (88.1) |

| PJ invagination | 273 (8.9) |

| Pancreaticogastrostomy | 95 (3.1) |

| Drain | |

| No | 160 (5.2) |

| Yes | 2,923 (94.8) |

| POPF | |

| Grade A | 1,498 (48.6) |

| Grade B | 1,400 (45.4) |

| Grade C | 185 (6.0) |

Values are presented as number only, mean ± standard deviation (median), or number (%).

COPD, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; PJ, pancreaticojejunostomy.

Predictors of clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula

Multivariable logistic regression was performed as described above to identify predictors of CR-POPF in the entire cohort. The following factors emerged: male sex (hazard ratio [HR], 1.141; p = 0.038), benign indications (HR, 1.103; p = 0.040), and receipt of NAC (HR, 1.238; p = 0.034). In addition, undergoing MIPD (HR, 1.267; p = 0.023), pancreatojejunostomy (PJ) invagination technique (HR, 1.306; p = 0.039), omitting drain placement (HR, 7.24; p < 0.001), and longer operative times (HR, 1.002; p = 0.002) were also significantly associated with CR-POPF formation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Final block of the backward conditional multivariable logistic regression for predictors of clinically relevant POPF among patients who had POPF following their pancreatoduodenectomy

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | Reference | |

| Female | 0.88 (0.75–0.99) | 0.038* |

| Indication | ||

| Malignant | Reference | |

| Benign | 1.10 (1.04–1.30) | 0.040* |

| Unknown | 0.38 (0.11–1.30) | 0.122 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.24 (1.08–1.56) | 0.034* |

| Approach | ||

| OPD | Reference | |

| MIPD | 1.27 (1.06–1.67) | 0.023* |

| Reconstruction type | ||

| PJ duct-to-mucosa | Reference | |

| PJ invagination | 1.31 (1.01–1.68) | 0.039* |

| PG | 0.90 (0.60–1.37) | 0.633 |

| Operative time | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.002* |

| Drain | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.14 (0.08–0.23) | <0.001* |

POPF, postoperative pancreatic fistula; CI, confidence interval; OPD, open pancreatoduodenectomy; MIPD, minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy; PJ, pancreaticojejunostomy; PG, pancreaticogastrostomy.

*p < 0.05, statistically significant.

Propensity score matched analysis between patients who underwent open pancreatoduodenectomy and minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy

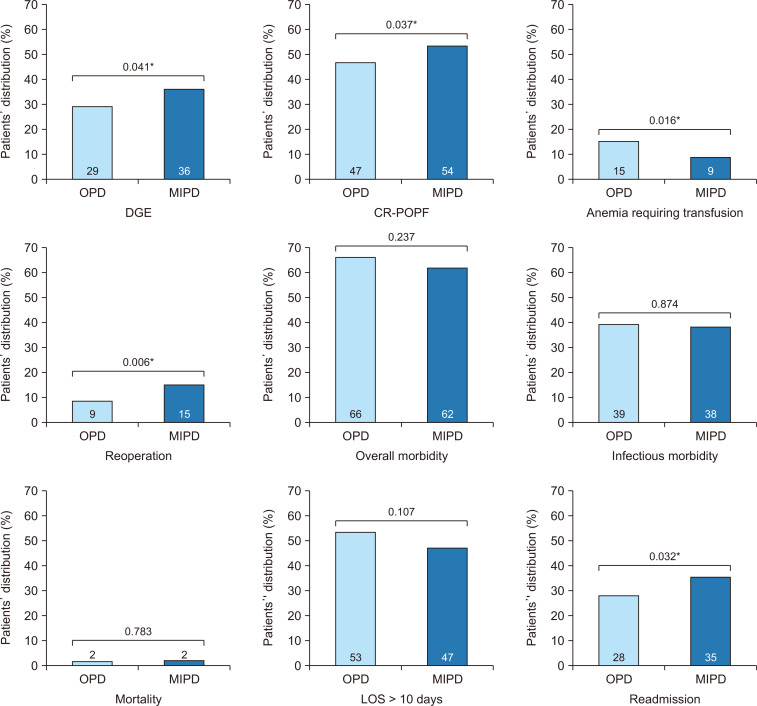

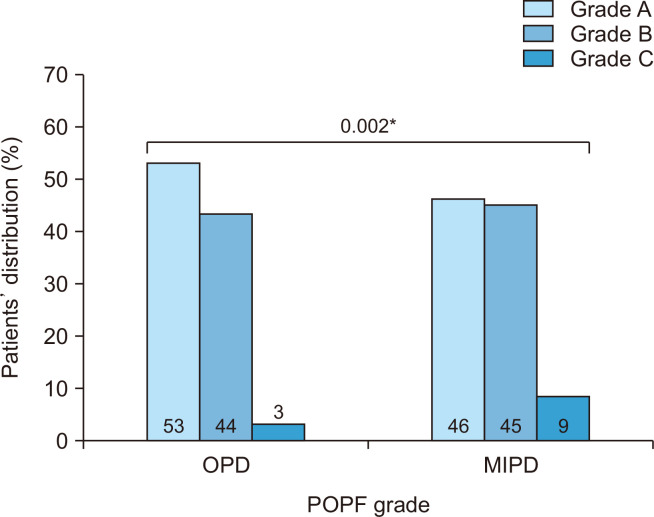

Propensity score matching of OPD and MIPD patients was conducted as described above to account for potential treatment selection bias (Table 3); 705 OPD patients were match to 235 MIPD peers (ratio 3:1). Prior to matching, cohorts were comparable with respect to age, race, BMI, comorbidity rates and several other risk factors. Notably however, more patients in the MIPD group had a duct size <3 mm, soft gland texture and less commonly received neoadjuvant radiation. After matching, well-balanced cohorts were generated with standardized mean differences for each variable ranging between 0.01 and 0.05 (Table 3). Overall morbidity, mortality and LOS were similar for the OPD and MIPD patients (Fig. 2). However, when occurrence of CR-POPF was assessed in the matched cohorts, significantly more patients who underwent MIPD developed CR-POPF compared to OPD (54.4% vs. 47.3% respectively, p = 0.037). Specifically, grade B POPF occurrence was not different (45.1% vs. 44.1%, p = 0.446) while grade C POPF occurred more commonly with MIPD (9.3% vs. 2.9%, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3). When comparing other specific morbidities of PD, significantly more patients undergoing MIPD experienced postoperative DGE (35.8% vs. 29.2%, p = 0.041) and required reoperation within 30 days (15.3% vs. 9.1%, p = 0.006), whereas fewer MIPD patients developed anemia requiring transfusion (8.9% vs. 15.2%, p = 0.016). The infectious complications between the two groups were comparable. The infectious complications between the two groups were comparable.

Table 3.

Comparison of OPD vs. MIPD patients who suffered a POPF following their pancreatoduodenectomy in the unmatched and 3:1 matched dataset

| Characteristic | Unmatched dataset | Matched dataset 3:1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPD | MIPD | p-value | OPD | MIPD | p-value | ||

| No. of patients | 2,843 | 240 | 705 | 235 | |||

| Age (yr) | 64.5 ± 11.9 | 63.3 ± 12.1 | 0.161 | 62.9 ± 12.8 | 63.3 ± 12.2 | 0.758 | |

| Sex | 0.019* | 0.970 | |||||

| Male | 1,666 (58.6) | 122 (50.8) | 367 (52.1) | 122 (51.9) | |||

| Female | 1,177 (41.4) | 118 (49.2) | 338 (47.9) | 113 (48.1) | |||

| Race | 0.275 | 0.828 | |||||

| White | 2,153 (75.7) | 174 (72.5) | 514 (72.9) | 173 (73.6) | |||

| Black | 167 (5.9) | 20 (8.3) | 63 (8.9) | 18 (7.7) | |||

| Others | 523 (18.4) | 46 (19.2) | 128 (18.2) | 44 (18.7) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.7 ± 6.4 | 28.7 ± 6.8 | 0.921 | 28.4 ± 6.0 | 28.7 ± 6.8 | 0.492 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| Hypertension | 1,544 (54.3) | 127 (52.9) | 0.678 | 359 (50.9) | 124 (52.8) | 0.624 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 570 (20.0) | 40 (16.7) | 0.207 | 118 (16.7) | 39 (16.6) | 0.960 | |

| COPD | 133 (4.7) | 8 (3.3) | 0.338 | 22 (3.1) | 8 (3.4) | 0.830 | |

| CHF | 10 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.357 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.999 | |

| ESRD | 7 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0.442 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.999 | |

| Risk factor | |||||||

| Smoking | 420 (14.8) | 38 (15.8) | 0.657 | 118 (16.7) | 36 (15.3) | 0.611 | |

| Steroids | 93 (3.3) | 11 (4.6) | 0.280 | 29 (4.1) | 11 (4.7) | 0.709 | |

| Weight loss | 269 (9.5) | 19 (7.9) | 0.430 | 70 (9.9) | 19 (8.1) | 0.403 | |

| Bleeding disorder | 56 (2.0) | 5 (2.1) | 0.903 | 13 (1.8) | 5 (2.1) | 0.783 | |

| Preoperative anemia | 7 (0.2) | 2 (0.8) | 0.105 | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0.738 | |

| Indication | 0.054 | 0.819 | |||||

| Malignancy | 1,954 (68.7) | 147 (61.3) | 426 (60.4) | 146 (62.1) | |||

| Benign | 874 (30.7) | 91 (37.9) | 274 (38.9) | 88 (37.4) | |||

| Unknown | 15 (0.5) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | |||

| Neoadjuvant therapy | |||||||

| NAC | 353 (12.4) | 23 (9.6) | 0.198 | 65 (9.2) | 23 (9.8) | 0.796 | |

| NAR | 1,357 (9.0) | 67 (5.1) | <0.001* | 22 (3.1) | 6 (2.6) | 0.658 | |

| Biliary stent | 1,338 (47.1) | 113 (47.1) | 0.995 | 325 (46.1) | 111 (47.2) | 0.763 | |

| Duct size (mm) | 0.001* | 0.822 | |||||

| <3 | 1,300 (45.7) | 132 (55.0) | 399 (56.6) | 130 (55.3) | |||

| 3–6 | 1,345 (47.3) | 84 (35.0) | 249 (35.3) | 83 (35.3) | |||

| >6 | 198 (7.0) | 24 (10.0) | 57 (8.1) | 22 (9.4) | |||

| Texture | 0.008* | 0.871 | |||||

| Soft | 2,050 (72.1) | 193 (80.4) | 570 (80.9) | 189 (80.4) | |||

| Intermediate | 264 (9.3) | 21 (8.8) | 53 (7.5) | 20 (8.5) | |||

| Hard | 529 (18.6) | 26 (10.8) | 82 (11.6) | 26 (11.1) | |||

| Reconstruction | 0.222 | 0.866 | |||||

| PJ duct-to-mucosa | 2,496 (87.8) | 219 (91.3) | 649 (92.1) | 214 (91.1) | |||

| PJ invagination | 259 (9.1) | 14 (5.8) | 38 (5.4) | 14 (6.0) | |||

| PG | 88 (3.1) | 7 (2.9) | 18 (2.6) | 7 (3.0) | |||

| Drain | 2,684 (94.4) | 239 (99.6) | 0.001* | 701 (99.4) | 234 (99.6) | 0.796 | |

Values are presented as number only, mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

OPD, open pancreatoduodenectomy; MIPD, minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy; POPF, postoperative pancreatic fistula; COPD, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; ESRD, end stage renal disease; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NAR, neoadjuvant radiation; PJ, pancreaticojejunostomy; PG, pancreaticogastrostomy.

*p < 0.05, statistically significant.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of key postoperative outcomes of open pancreatoduodenectomy (OPD) vs. minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy (MIPD) in the matched dataset of patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy complicated by a postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF). DGE, delayed gastric emptying; CR-POPF, clinically relevant POPF; LOS, length of stay. *p < 0.05, statistically significant.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of POPF grade distribution in patients who underwent open pancreatoduodenectomy (OPD) vs. minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy (MIPD) in the matched dataset. POPF, postoperative pancreatic fistula. *p < 0.05, statistically significant.

Propensity score matched analysis between patients who underwent laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy and robotic pancreatoduodenectomy

Table 4 summarizes LPD and RPD cohorts before and after matching. Patient characteristics were generally comparable among LPD and RPD patients except more patients who underwent RPD had a benign indication and underwent PJ duct-to-mucosa reconstruction, and less had received neoadjuvant radiation. As above, propensity score matching generated balanced cohorts.

Table 4.

Comparison of LPD vs. RPD patients who suffered a POPF following their pancreatoduodenectomy in the unmatched and 3:1 matched dataset

| Characteristic | Unmatched dataset | Matched dataset 1:2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPD | RPD | p-value | LPD | RPD | p-value | ||

| No. of patients | 60 | 180 | 47 | 47 | |||

| Age (yr) | 63.9 ± 11.5 | 36.2 ± 12.3 | 0.701 | 63.3 ± 11.9 | 61.6 ± 11.2 | 0.499 | |

| Sex | 0.456 | 0.408 | |||||

| Male | 28 (46.7) | 94 (52.2) | 23 (48.9) | 27 (57.4) | |||

| Female | 32 (53.3) | 86 (47.8) | 24 (5.1) | 20 (42.6) | |||

| Race | 0.315 | 0.948 | |||||

| White | 39 (65.0) | 135 (75.0) | 31 (66.0) | 32 (68.1) | |||

| Black | 6 (10.0) | 14 (7.8) | 6 (12.8) | 5 (10.6) | |||

| Others | 15 (25.0) | 31 (17.2) | 10 (21.3) | 10 (21.3) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.2 ± 6.5 | 28.9 ± 6.9 | 0.523 | 28.2 ± 6.6 | 30.2 ± 8.5 | 0.204 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| Hypertension | 33 (55.0) | 94 (52.2) | 0.709 | 26 (55.3) | 28 (59.6) | 0.677 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13 (21.7) | 27 (15.0) | 0.230 | 8 (17.0) | 4 (8.5) | 0.216 | |

| COPD | 0 (0) | 8 (4.4) | 0.097 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 0.315 | |

| CHF | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.999 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.999 | |

| ESRD | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.999 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.999 | |

| Risk factor | |||||||

| Smoking | 11 (18.3) | 27 (15.0) | 0.540 | 9 (19.1) | 6 (12.8) | 0.398 | |

| Steroids | 2 (3.3) | 9 (5.0) | 0.593 | 2 (4.3) | 3 (6.4) | 0.646 | |

| Weight loss | 8 (13.3) | 11 (6.1) | 0.073 | 8 (17.0) | 6 (12.8) | 0.562 | |

| Bleeding disorder | 1 (1.7) | 4 (2.2) | 0.794 | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4.3) | 0.557 | |

| Preoperative anemia | 1 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 0.412 | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0.315 | |

| Indication | 0.039* | 0.517 | |||||

| Malignancy | 38 (63.3) | 109 (60.6) | 32 (68.1) | 29 (61.7) | |||

| Benign | 20 (33.3) | 71 (39.4) | 15 (31.9) | 18 (38.3) | |||

| Unknown | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Neoadjuvant therapy | |||||||

| NAC | 7 (11.7) | 16 (8.9) | 0.527 | 4 (8.5) | 5 (10.6) | 0.726 | |

| NAR | 5 (8.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0.001* | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.1) | 0.557 | |

| Biliary stent | 27 (45.0) | 86 (47.8) | 0.709 | 21 (44.7) | 18 (38.3) | 0.530 | |

| Duct size (mm) | 0.329 | 0.689 | |||||

| <3 | 31 (51.7) | 101 (56.1) | 26 (55.3) | 23 (48.9) | |||

| 3–6 | 20 (33.3) | 64 (35.6) | 15 (31.9) | 19 (40.4) | |||

| >6 | 9 (15.0) | 15 (8.3) | 6 (12.8) | 5 (10.6) | |||

| Texture | 0.002* | 0.931 | |||||

| Soft | 39 (65.0) | 154 (85.6) | 33 (70.2) | 33 (70.2) | |||

| Intermediate | 10 (16.7) | 11 (6.1) | 7 (14.9) | 8 (17.0) | |||

| Hard | 11 (18.3) | 15 (8.3) | 7 (14.9) | 6 (12.8) | |||

| Reconstruction | 0.009* | 0.287 | |||||

| PJ duct-to-mucosa | 50 (83.3) | 169 (93.9) | 42 (89.4) | 42 (89.4) | |||

| PJ invagination | 5 (8.3) | 9 (5.0) | 5 (10.6) | 3 (6.4) | |||

| PG | 5 (8.3) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.3) | |||

| Drain | 60 (100) | 179 (99.4) | 0.563 | 47 (100) | 47 (100) | >0.999 | |

Values are presented as number only, mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

LPD, laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy; RPD, robotic pancreatoduodenectomy; POPF, postoperative pancreatic fistula; COPD, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; ESRD, end stage renal disease; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NAR, neoadjuvant radiation; PJ, pancreaticojejunostomy; PG, pancreaticogastrostomy.

*p < 0.05, statistically significant.

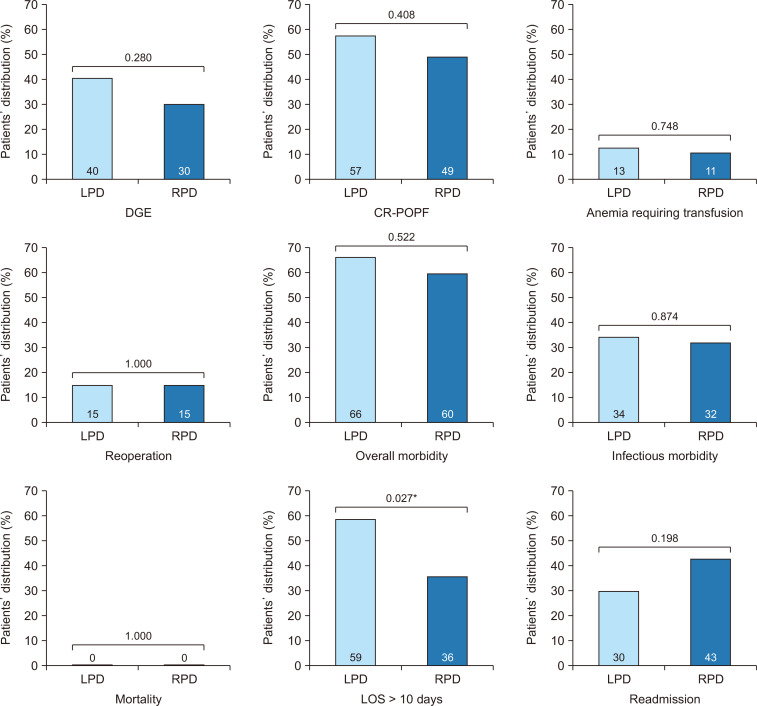

Outcomes were then assessed in the matched cohorts. There were no differences between LPD and RPD for overall morbidity (65.7% for LPD and 60.4% for RPD, p = 0.522) and mortality (0.0% for LPD and RPD, p > 0.999). When comparing specific complications, rates of CR-POPF were comparable for LPD and RPD patients (56.8% vs. 49.3%, p = 0.408). Similar rates of DGE (40.2% for LPD and 29.7% for RPD, p = 0.280), anemia (13.2% for LPD and 10.9% for RPD, p = 0.748), reoperation (15.0% for LPD and RPD, p > 0.999), infectious morbidity (34.2% for LPD and 32.1% for RPD, p = 0.740), and readmission (29.9% for LPD and 43.1% for RPD, p = 0.198) were also observed. However, significantly more patients experienced prolonged LOS (>10 days) after LPD compared to RPD (58.7% vs. 35.5%, p = 0.027) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of key postoperative outcomes of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) vs. robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy (RPD) in the matched dataset of patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy complicated by a postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF). DGE, delayed gastric emptying; CR-POPF, clinically relevant POPF; LOS, length of stay. *p < 0.05, statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Driven by our hypothesis that the likelihood of having a CR-POPF would be higher in MIPD versus OPD, we performed a study utilizing a national prospectively maintained dataset of PD patients who developed POPF. In our study, CR-POPF occurred more commonly after MIPD compared to OPD while controlling for potential confounders through multivariable analysis and propensity score matching. These MIPD patients also had higher reoperation, readmission, and DGE rates as compared to patients undergoing OPD. On subgroup analysis of LPD and RPD patients, neither minimally invasive approach appeared protective as similar rates of CR-POPF were observed. Our analysis suggests that POPF following MIPD tends to be of a higher grade, subsequently leading to a more complex postoperative course.

The effect of PD approach on POPF rates has been extensively examined in the literature. When considering LPD, POPF rates are generally reported to occur at comparable rates to OPD in both prospective and retrospective studies [4,17]. For example, in the Spanish PADULAP trial which compared LPD to OPD, overall POPF and CR-POPF rates were similar for either approach despite a decrease in severe complication rates and LOS with LPD [24]. In contrast, the LEOPARD II trial, which randomized patients to LPD or OPD at high-volume centers, reported comparable overall POPF rates for OPD and LPD, but increased mortality with LPD, prompting early termination [3]. Specifically, two out of five patients in the LPD group died as a consequence of postpancreatectomy hemorrhage and one from a grade C POPF. This is consistent with our findings that despite similar overall rates of POPF for MIPD and OPD, the clinical consequence of POPF is more severe when it occurs after MIPD with more patients in our cohort undergoing MIPD requiring readmission and reoperation, as well as DGE.

Incidence and impact of POPF have similarly been examined for RPD in multiple studies. A recent ACS NSQIP propensity-matched report found no difference in the rates of CR-POPF among OPD and RPD patients stratified by negligible, low or intermediate FRS [25]. Interestingly, patients at high risk for POPF were less likely to experience a CR-POPF after RPD (19.4% vs. 32.9%; p = 0.007). Yet, no differences in CR-POPF rates were noted between LPD and RPD for any risk group, similar to our study. While a specific comparison of OPD and RPD approaches was not carried out in our study, this equivalence between LPD and RPD is in concordance with our findings.

A clear biological explanation of this clinical observation of higher CR-POPF in MIPD remains missing. Increased adhesion formation after open surgery is a proposed mechanism for the decreased severity of POPF in OPD relative to minimally invasive surgery. Multiple trials, particularly in gynecology, have demonstrated that patients undergoing minimally invasive surgical approaches develop fewer adhesions than those undergoing a laparotomy [26–28]. This is attributed to possible differences in tissue handling and exposure to desiccation [26–28]. In the experimental setting, exposure of carrier beads (Cytodex 3, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to short bouts of ambient air (15 minutes) led beads to rapidly adhere to a monolayer of cultured human mesothelial cells compared to warm humidified culture atmosphere [29]. Thus, adhesion formation after OPD containing and mitigating the severity of POPF when it occurs is one possible reason for this finding.

In addition to the operative approach, this study reported on risk factors for CR-POPF incidence among patients who develop any grade POPF including male sex, benign indication, lack of drain placement, PJ invagination technique, NAC receipt, and longer operative times. In the seminal study by Callery et al. [21] which established the FRS, factors associated with CR-POPF formation include histopathology, pancreatic duct size, pancreatic texture, and estimated blood. Modifications to the initial proposed risk score have since been published [21,30–32]. While some variables overlap with those reported in this study, a key distinction to these risk score models relates to patient selection. More recent predictive models based on the new International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery definition included novel factors such as extended lymphadenectomy, serum albumin levels, and hypertension, but are restricted to single institutions and few operative factors were identified [10,33,34]. These aforementioned risk score and predictive models do not discriminate between various grades or clinical relevance of POPF. The present study is unique as we describe a model that incorporates clinical and demographic factors that may help predict CR-POPF formation specific to patients who develop any POPF based on the operative approach.

Important limitations should be noted, some of which are inherent to retrospective dataset analyses. Patients included were non-randomized, concerning selection bias for surgical approach and subsequent CR-POPF risk based on anatomic tumor features. In an effort to counteract this effect, propensity score matching and multivariable adjustment were employed but may be insufficient. NSQIP data is limited to select hospitals and therefore may not be representative of the true national landscape. Details on surgeon or facility volume and experience are not provided. As MIPD techniques are not widely adopted nationally, it is possible that a larger percentage of those cases were performed by surgeons who have not yet overcome their respective learning curves. Additionally, with greater adoption of MIPD techniques, temporal trends in improvement may appear.

About 7,000 patients were excluded from this study due to missing or unknown technical information (Fig. 1). While these data points were statistically determined to be missing at random, it is possible this may have affected our results. Nevertheless, even after applying strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, there remained a notable sample size of 3,083 patients, all of which developed POPF, to address the study’s stated hypothesis.

In this study, in patients who developed any grade POPF after a PD, MIPD, regardless of a laparoscopic or robotic approach, was associated with significantly higher rates of CR-POPF than OPD. Caution is warranted prior to the widespread implementation of MIPD.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.7602/jmis.2024.27.2.95.

Notes

Ethical statements

This study was deemed exempt from informed consent by the Institutional Review Board as it utilized de-identified national registry data (No. 18-159).

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Project administration, Visualization, Software: FSD, SAN

Investigation, Methodology: JHC, RTK, RN, DJ, TA, RS, FSD, PS, IS, AP, SAN

Resources: JHC, RTK, CW, FSD, SAN

Validation: CW, FSD, SAN

Supervision: RMW, FSD, SAN

Writing–original draft: JHC, RTK

Writing–review & editing: All authors

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding/support

None.

Data availability

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) is a publicly available Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant data file from the American College of Surgeons that can be requested through instructions on the following link: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/data-and-registries/acs-nsqip/participant-use-data-file/

References

- 1.Eskander MF, Cloyd JM. Predicting post-operative pancreatic fistula: one size may not fit all. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2021;10:113–115. doi: 10.21037/hbsn-20-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nahm CB, Connor SJ, Samra JS, Mittal A. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: a review of traditional and emerging concepts. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:105–118. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S120217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vining CC, Kuchta K, Berger Y, et al. Robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy decreases the risk of clinically relevant post-operative pancreatic fistula: a propensity score matched NSQIP analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2021;23:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin H, Qiu J, Zhao Y, Pan G, Zeng Y. Does minimally-invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy have advantages over its open method? A meta-analysis of retrospective studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adam MA, Choudhury K, Dinan MA, et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer: practice patterns and short-term outcomes among 7061 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;262:372–377. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Underwood PW, Gerber MH, Hughes SJ. Pitfalls of minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Pancreat Cancer. 2019;2:10.21037/apc.2018.12.02. doi: 10.21037/apc.2018.12.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen K, Pan Y, Liu XL, et al. Minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary disease: a comprehensive review of literature and meta-analysis of outcomes compared with open surgery. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:120. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0691-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nassour I, Wang SC, Christie A, et al. Minimally invasive versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: a propensity-matched study from a national cohort of patients. Ann Surg. 2018;268:151–157. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahdaleh FS, Naffouje SA, Hanna MH, Salti GI. Impact of neoadjuvant systemic therapy on pancreatic fistula rates following pancreatectomy: a population-based propensity-matched analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:747–756. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04581-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia W, Zhou Y, Lin Y, et al. A predictive risk scoring system for clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:5719–5728. doi: 10.12659/MSM.911499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery. 2017;161:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palanivelu C, Rajan PS, Rangarajan M, et al. Evolution in techniques of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a decade long experience from a tertiary center. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:731–740. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Hilst J, de Rooij T, Bosscha K, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): a multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:199–207. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nickel F, Haney CM, Kowalewski KF, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2020;271:54–66. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai Y, Lu X, Zhu X, Ju H, Sun W, Wu W. Histological tumor response assessment in colorectal liver metastases after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: impact of the variation in tumor regression grading and peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration. J Cancer. 2019;10:5852–5861. doi: 10.7150/jca.31493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magge D, Zenati M, Lutfi W, et al. Robotic pancreatoduodenectomy at an experienced institution is not associated with an increased risk of post-pancreatic hemorrhage. HPB (Oxford) 2018;20:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendoza AS, Han HS, Yoon YS, Cho JY, Choi Y. Laparoscopy-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy as minimally invasive surgery for periampullary tumors: a comparison of short-term clinical outcomes of laparoscopy-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy and open pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:819–824. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daley J, Khuri SF, Henderson W, et al. Risk adjustment of the postoperative morbidity rate for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care: results of the National Veterans Affairs Surgical Risk Study. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:328–340. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(97)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiloach M, Frencher SK, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller BC, Christein JD, Behrman SW, et al. A multi-institutional external validation of the fistula risk score for pancreatoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:172–180. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, Chaikof EL, Vollmer CM. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kantor O, Talamonti MS, Pitt HA, et al. Using the NSQIP pancreatic demonstration project to derive a modified fistula risk score for preoperative risk stratification in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224:816–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American College of Surgeons (ACS), author User guide for the 2017 ACS NSQIP procedure targeted participant use data file (PUF) [Internet] ACS; 2018. [cited 2024 April 25]. Available from: https://www.facs.org/media/vcdilnwc/pt_nsqip_puf_userguide_2017.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poves I, Burdío F, Morató O, et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between laparoscopic and open approach for pancreatoduodenectomy: the PADULAP randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;268:731–739. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vining CC, Kuchta K, Schuitevoerder D, et al. Risk factors for complications in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a NSQIP analysis with propensity score matching. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122:183–194. doi: 10.1002/jso.25942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavic SM, Kavic SM. Adhesions and adhesiolysis: the role of laparoscopy. JSLS. 2002;6:99–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lundorff P, Hahlin M, Källfelt B, Thorburn J, Lindblom B. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in tubal pregnancy: a randomized trial versus laparotomy. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:911–915. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molinas CR, Binda MM, Manavella GD, Koninckx PR. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery: what do we know about the role of the peritoneal environment? Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2010;2:149–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer A, Koopmans T, Ramesh P, et al. Post-surgical adhesions are triggered by calcium-dependent membrane bridges between mesothelial surfaces. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3068. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16893-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trudeau MT, Casciani F, Ecker BL, et al. The fistula risk score catalog: toward precision medicine for pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2022;275:e463–e472. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lao M, Zhang X, Guo C, et al. External validation of alternative fistula risk score (a-FRS) for predicting pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mungroop TH, Klompmaker S, Wellner UF, et al. Updated alternative fistula risk score (ua-FRS) to include minimally invasive pancreatoduodenectomy: pan-European validation. Ann Surg. 2021;273:334–340. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang JY, Huang J, Zhao SY, Liu X, Xiong ZC, Yang ZY. Risk factors and a new prediction model for pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1897–1906. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S305332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu J, Ren CY, Wang J, Cui W, Zhang JJ, Wang YJ. Establishment of risk prediction model of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy: 2016 edition of definition and grading system of pancreatic fistula: a single center experience with 223 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:257. doi: 10.1186/s12957-021-02372-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.