Tracheal obstruction may be due to trauma, infection, tumour, or aspirated foreign bodies. Despite improvements in the design of tracheal tubes, however, tracheal stenosis after intubation remains an important cause of tracheal obstruction, which may be life threatening. We describe a patient with tracheal stenosis which was initially misdiagnosed as asthma after prolonged tracheal intubation.

Case report

A 16 year old man, with a history of asthma that had needed hospital admission on several occasions, was referred to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of acute severe asthma. Seven weeks earlier he had sustained a head injury in a road traffic accident and had been mechanically ventilated through an oral tracheal tube for 84 hours at another hospital. Subsequently he had been transferred to a neurological rehabilitation unit. Two days after admission he complained of exertional dyspnoea and wheeze. Although treatment with bronchodilators was started, his symptoms worsened progressively over the next two weeks, and he became acutely dyspnoeic at rest. He was transferred to an acute medical ward but continued to deteriorate despite receiving nebulised bronchodilators, intravenous hydrocortisone, aminophylline, and antibiotics. He became exhausted within 24 hours and was thus referred to our intensive care unit for further management.

On admission he was in extremis and had tachypnoea (respiratory rate 30/min), a virtually silent chest, and hypercarbia (partial pressure of carbon dioxide 9.3 kPa) on arterial blood gas analysis. We decided to intubate and ventilate him. After intravenous induction of anaesthesia, laryngoscopy was performed, with a good view of a normal glottis, but it was impossible to pass a tracheal tube (size 7-9 mm internal diameter) further than 2 cm beyond his vocal cords before firm resistance was felt. It was similarly impossible to pass even a flexible gum elastic bougie beyond the obstruction. We managed to ventilate him adequately with a bag, valve, and mask. We decided that instead of acute severe asthma the patient had a severe tracheal stenosis secondary to tracheal intubation after his head injury. Surgical help was sought quickly, and both emergency cricothyroidotomy and tracheostomy were considered. It was almost certain, however, that the stenosis extended beyond the level of the cricothyroid membrane and probably below the level of a surgical tracheostomy. We therefore decided to make another attempt to intubate the trachea by way of the oral route. A paediatric tracheal tube (4.5 mm internal diameter) was threaded on to a semirigid introducer, which was allowed to protrude 5 cm beyond the end of the tube. The tip of the introducer was then passed through the vocal cords until resistance was felt. The introducer was then firmly pushed with a twisting motion until a sudden give was felt as it passed through and dilated the stenosis. With some difficulty, the tracheal tube was passed, using the introducer as a guide. Once intubated, the patient was easy to ventilate without excessively high airway pressures, and there was no wheeze on auscultation of the chest. The patient was referred to the regional cardiothoracic centre for further management.

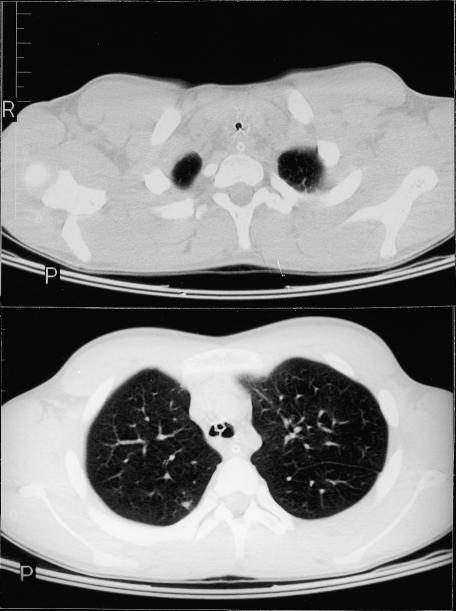

A computed tomogram showed that the trachea was narrowed to the diameter of the 4.5 mm tracheal tube over a 3 cm length from the thyroid isthmus to the manubrium (figs 1 and 2). The patient was transferred to the operating theatre for tracheal dilation. A rigid bronchoscopy was performed under general anaesthesia, and the trachea was serially dilated with bougies until it was large enough to accommodate a 6.5 mm uncuffed tracheal tube. The patient was returned to the intensive care unit where intravenous dexamethasone was given. As there was a notable air leak around the tube 24 hours later, sedation was discontinued and the patient was extubated. There was no evidence of upper airway obstruction and the patient was discharged back to the rehabilitation unit five days later. He was also referred to a specialist centre for consideration of definitive tracheal reconstructive surgery.

Figure 1.

Computed tomogram showing tracheal stenosis throughout length of trachea (reproduced with patient's permission)

Discussion

Several major sequelae of prolonged tracheal intubation were recognised after the introduction of mechanical ventilation for respiratory support during the poliomyelitis epidemics of the 1950s, including laryngeal damage, subglottic stenosis, and tracheal stenosis at the site of the tracheal cuff. Studies into stenosis at the cuff site showed that the main cause was the pressure exerted on the tracheal mucosa by the cuff.1 A cuff pressure greater than about 30 mm Hg exceeds the mucosal capillary perfusion pressure, causing mucosal ischaemia, which may lead to ulceration and chondritis of the tracheal cartilages.2 These circumferential lesions heal by fibrosis, leading to a progressive tracheal stenosis. The incidence of tracheal damage and tracheal stenosis after intubation can be reduced by the use of tracheal tubes with cuffs that have a high volume and large area of contact with the tracheal mucosa, thus minimising the pressure exerted.3,4 The use of such high volume, low pressure cuffs is now standard practice on intensive care units. However, tracheal stenosis may still occur, and in one prospective study of critically ill patients, 11% of patients who had been intubated with high volume, low pressure cuffed tubes developed tracheal stenoses that were 10-50% of their tracheal diameter at the cuff site.5

Tracheal stenosis after intubation usually presents as shortness of breath and either or both inspiratory stridor and expiratory wheeze on exertion. The wheeze heard in acute upper airway obstruction is classically described as monophonic whereas that heard in acute asthma is described as polyphonic. However, this distinction may not be made—as in the case of our patient—or may not actually suggest the correct diagnosis. Tracheal stenosis after intubation is therefore often misdiagnosed as asthma and the diagnosis is not suggested at initial presentation in as many as 44% of patients.6–8 Symptoms do not usually occur at rest until the trachea has stenosed to 30% of its original size, and it may take as long as three months before most stenoses are seen by a doctor.9

A history of progressive dyspnoea and wheeze unresponsive to bronchodilators, coupled with a high index of suspicion in patients who have recently undergone a prolonged period of tracheal intubation, are probably the most important indicators of tracheal stenosis. The diagnosis may be confirmed with plain radiography, computed tomography, or endoscopy. Linear tomography has been recommended as the technique of choice, although this may be more difficult to arrange than computed tomography.6 Although flow-volume loops exhibit a characteristic reduction in peak expiratory flow, with a plateau in the expiratory curve, their interpretation may be complicated by concomitant lung disease, and they are not recommended as a reliable diagnostic technique.6,9

Although there have been reports of the successful treatment of tracheal stenosis with steroid regimens,10,11the mainstay of treatment for symptomatic lesions is surgical. Rigid bronchoscopy and tracheal dilation, possibly with placement of a stent, may be the only treatment required for less serious lesions and can be used to provide time to plan a definitive procedure in more severe cases. Tracheal reconstruction requires major surgery, with a mortality of about 3%.6,9

In summary, tracheal obstruction may be due to trauma, tumour, infection, aspirated foreign bodies, or tracheal stenosis. Prolonged periods of tracheal intubation may lead to progressive tracheal stenosis presenting weeks or months later. Tracheal stenosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any patient who has recently been intubated in an intensive care unit and who presents with exertional dyspnoea or monophonic wheeze, particularly when it is unresponsive to bronchodilators. Such patients require immediate referral to hospital.

Figure 2.

Computed tomograms showing (top) trachea narrowed to size of paediatric tracheal tube and (bottom) paediatric tracheal tube below level of stenosis within trachea of normal calibre (reproduced with patient's permission)

Prolonged intubation may cause tracheal stenosis, with progressive dyspnoea and wheeze easily misdiagnosed as asthma

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Cooper JD, Grillo HC. Experimental production and prevention of injury due to cuffed tracheal tubes. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1969;129:1235–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowlson GTG, Bassett HFM. The pressures exerted on the trachea by tracheal inflatable cuffs. Br J Anaesth. 1970;42:834–837. doi: 10.1093/bja/42.10.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathias DB, Wedley JR. The effects of cuffed tracheal tubes on the tracheal wall. Br J Anaesth. 1974;46:849–852. doi: 10.1093/bja/46.11.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The price of therapeutic artificial ventilation [editorial] Lancet. 1973;135:1161–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stauffer JL, Olson DE, Petty TL. Complications and consequences of tracheal intubation and tracheostomy. A prospective study of 150 critically ill adult patients. Am J Med. 1981;70:65–76. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grillo HC, Donahue DN. Post-intubation tracheal stenosis. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;8:370–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Partridge MR, Flood-Page P. Multiple tracheal strictures following mechanical ventilation. Respir Med. 1997;91:503–504. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(97)90118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brichet A, Verkindre C, Dupont J, Carlier ML, Darras J, Wurtz A, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to management of post-intubation tracheal stenoses. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:888–889. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d32.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews MJ, Pearson FG. Analysis of 59 cases of tracheal stenosis following tracheostomy with cuffed tube and assisted ventilation, with special reference to diagnosis and treatment. Br J Surg. 1973;60:208–212. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croft CB, Zub Z, Borowiecki B. Therapy of iatrogenic subglottic stenosis: a steroid/antibiotic regimen. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:482–489. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197903000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braidy J, Breton G, Clement L. Effect of corticosteroids on postintubation tracheal stenosis. Thorax. 1989;44:753–755. doi: 10.1136/thx.44.9.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]