The NHS is becoming a steadily less attractive place for pharmaceutical companies to conduct clinical trials. That was the message delivered last week by Tadataka Yamada, chairman of research and development for SmithKline Beecham, at a meeting on how to make research and development in London more attractive to funders.

Pharmaceutical clinical research has increased worldwide in the past decade, but Britain's market share has fallen, even though the absolute quantity has remained about the same. The industry spends about £150m ($210m) on research in the NHS, but, warned Mr Yamada, the amount could fall if conditions did not improve. The companies are global, and research might easily be moved to countries that offer higher quality at lower costs.

The biggest problem is with the timeliness and the quality of research. The processes of ethics and research committees approving research are slow and confused. Sometimes trials may be completed in other countries before they even begin in Britain. Every day matters to pharmaceutical companies because they may be losing sales of millions of dollars a day.

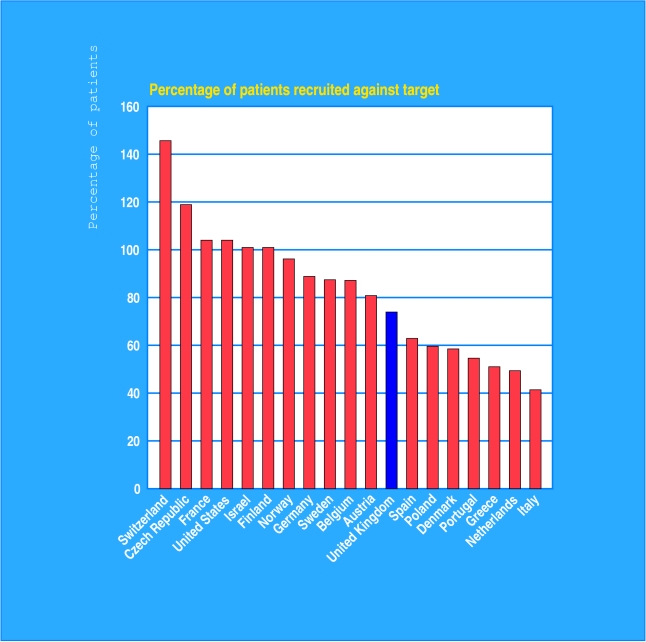

Britain has a bad record in recruitment to trials, recruiting less than 80

of the patients promised. At least 13 countries have better records of recruitment, with six—including the Czech Republic, the United States, and France—recruiting 100

of the target or more. Another problem is the cleanliness of the data. GlaxoWellcome found 30 queries in every 100 pages of data, a far higher rate than in most other countries. Clinicians are hard pressed and poorly trained, and research management is weak.

The problems of poor quality are compounded by Britain's high costs. Only the United States tends to be more expensive than Britain, and it produces high quality research. Countries that produce as high or even higher quality research—such as Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland—have costs that may be half as much per patient. Mr Yamada also emphasised the lack of transparency in British costs, with big variations around the NHS in overheads charged.

These problems amount, said a report produced for the conference, to the hallmarks of a classic decline in an ailing British industry. Inherited strength is eroding. New competitors are offering greater choice, lower costs, and higher quality, and complacent and insular management is unaware of its declining market.

Figure.

Britain has a poor record in recruitment to clinical trials, recruiting less than 80% of the patients promised