Complementary and alternative medicine is defined as “diagnosis, treatment and/or prevention which complements mainstream medicine by contributing to a common whole, by satisfying a demand not met by orthodoxy or by diversifying the conceptual frameworks of medicine.”1 It comprises a confusingly large and heterogeneous array of techniques, with both therapeutic and diagnostic approaches (table 1).

Summary points

The one year prevalence for use of complementary and alternative medicine is around 20% and is predicted to rise

Some of the reasons for this popularity amount to a biting criticism of conventional medicine

At present much complementary and alternative medicine is still opinion based

Table 1.

Examples of techniques used in complementary and alternative medicine

| Technique | Method | Indication (examples) | Serious risks (examples) | Benefits* | Risk benefit analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture2 | Therapeutic /diagnostic | Chronic pain | Tissue trauma, infections (rare)† | No convincing evidence | Uncertain |

| Acupuncture3 | Therapeutic /diagnostic | Nausea | Tissue trauma, infections (rare)† | Convincing evidence | Positive |

| Aromatherapy4 | Therapeutic | Various | Allergic reaction, carcinogenic potential in some oils | Good evidence for relaxing effects | Uncertain |

| Chelation therapy5 | Therapeutic | Intermittent claudication | Kidney damage, electrolyte imbalances† | No convincing evidence | Negative |

| Chiropractic6 | Therapeutic /diagnostic | Back pain | Vertebral or carotid artery dissection† | Promising but not convincing evidence for acute or chronic back pain | Uncertain |

| Herbalism7 8 | Therapeutic | (St John's wort for depression‡) | Increased risk of bleeding, interaction with numerous drugs | Clear evidence that it is superior to placebo | Positive |

| (Ginkgo biloba for intermittent claudication‡) | Increased risk of bleeding, interaction with anticoagulants | Clear evidence that it is superior to placebo | Positive | ||

| Homoeopathy9 | Therapeutic /diagnostic | Various | No serious direct risks of highly dilute remedies | No clear evidence for clinical effectiveness for any condition | Uncertain |

| Iridology10 | Diagnostic | NA (diagnostic method) | False positive or false negative diagnosis | No convincing evidence | Negative |

| Massage11 | Therapeutic /diagnostic | Back pain | No serious direct risks | No convincing evidence | Uncertain |

| Reflexology12 | Therapeutic /diagnostic | Various | No serious direct risks | No convincing evidence for clinical effectiveness for any condition | Uncertain |

| Spiritual healing13 | Therapeutic /diagnostic | Various | No serious direct risks | No convincing evidence for clinical effectiveness for any condition | Uncertain |

Evidence based on recent systematic reviews or meta-analyses.

Fatalities have occurred.

As examples of one specific herbal remedy.

NA=not applicable

Complementary and alternative medicine is popular

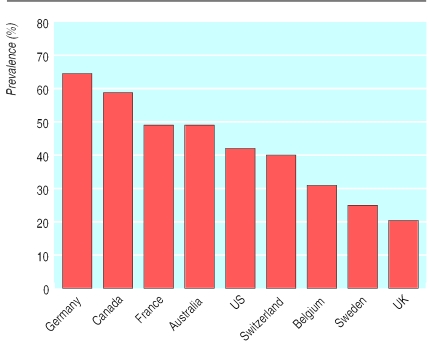

A recent telephone survey on the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United Kingdom yielded a one year prevalence of 20%.14 Herbalism, aromatherapy, homoeopathy, acupuncture, massage, and reflexology were among the most popular. This level of use may seem impressive but, compared with other countries, it is low (figure). National differences are difficult to interpret. To some they indicate that in the United Kingdom complementary and alternative medicine will grow to match its popularity in Germany or France, where, contrary to the United Kingdom, it is mostly practised by medically trained doctors.

Complex reasons for popularity

The exact reasons for the popularity of complementary and alternative medicine are complex; they change with time and space, they may vary from therapy to therapy, and they are different from one individual to another—for example, a patient with AIDS will have other motives than someone who is “worried well.” Reporting on complementary and alternative medicine in the British daily press is considerably more enthusiastic than that for conventional medicine.15 Also complementary and alternative medicine is largely practised privately. There is an intriguing, positive correlation between signs of affluence and the sales figures of commercial complementary and alternative medicine products.16

In essence, therefore, no single determinant of the present popularity of complementary and alternative medicine exists, but there is a broad range of interacting positive and negative motivations. Some of these amount to a biting criticism of our modern healthcare system. Regardless of whether this criticism is valid or not, it is often deeply felt by those who turn towards complementary and alternative medicine, and mainstream medicine would be well advised to consider it seriously.

Motivations for trying complementary and alternative medicine

Positive motivations

Perceived effectiveness

Perceived safety

Philosophical congruence: “Zeitgeist”; spiritual dimension; emphasis on holism; embracing all things natural; active role of patient; explanations intuitively acceptable

Control over treatment

“High touch, low tech”

Good patient/therapist relationship: enough time available; on equal terms; emotional factors; empathy

Non-invasive nature

Accessibility

Pleasant therapeutic experience

Affluence

Negative motivations

Dissatisfaction with (some aspects of) conventional health care: ineffective for certain conditions; serious adverse effects; poor doctor-patient relationship; insufficient time with doctor; waiting lists; “high tech, low touch”

Rejection of science and technology

Rejection of “the establishment”

Desperation

Difficulties in research

Many providers of complementary and alternative medicine are convinced that their therapy defies the “straightjacket” of reductionist research. They argue that it is individualised, holistic, intuitive, etc, and call for a “paradigm shift” in research. Usually these arguments are based on a series of misunderstandings, and often the problems can be resolved by clearly defining the research question and subsequently finding the research tool that optimally matches it. If the aim is to test the effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicine, randomised controlled trials usually provide the least biased method for finding a reliable answer.17

While few obstacles to research exist in principle, there are many in practice. Complementary and alternative medicine lacks both a research tradition and a research infrastructure and therefore fails to attract experienced researchers. Most importantly perhaps, the orthodox attitude remains highly (some would say destructively) sceptical, and as a consequence the funding of research is dismal.18

Opinion based medicine

Numerous indicators suggest that complementary and alternative medicine is largely opinion based. In the course of writing a strictly evidence based reference book of complementary and alternative medicine, I extracted all complementary therapies recommended for defined medical conditions in seven recent and seemingly authoritative books on the subject. Subsequently, I contrasted the results with the hard evidence from systematic reviews. More than 100 different complementary therapies were recommended for asthma, while systematic reviews failed to back up a single treatment for this indication.19 There was little agreement between the seven books. For instance, rarely was one treatment for asthma recommended by more than two authors. The exceptions were acupuncture, which was backed by four authors, and homoeopathy, which was backed by six authors. Yet neither of these treatments was supported by acceptable evidence.20,21 Even more surprisingly, less than half of these authors recommended St John's wort for depression, which happens to be of proved effectiveness.7 Opinions that often contradict the existing evidence seem to dominate complementary and alternative medicine, and this highlights the necessity of bringing opinion into line with evidence. The best way to achieve this is through rigorous research and the broad dissemination of its findings.

Hard evidence is scarce

If there are no funds there will be no research. If there is no research, we will be unable to find out whether complementary and alternative medicine does more good than harm. Yet this is the central question destined to determine its role in future health care. Simple answers or broad generalisations are not possible. Each of the numerous techniques has to be evaluated separately and on its own merits. Some forms of complementary and alternative medicine are safe but others aren't; some are effective while others may be pure placebos (see table 1).

It seems blatantly obvious that only well designed clinical investigations can establish the truth. Those who would prefer to bypass rigorous research—for example, by shifting the discussion towards patients' preference—and hope to integrate unproved treatments into routine health care are unlikely to succeed in the long run. Those who believe that regulation is a substitute for evidence will find that even the most meticulous regulation of nonsense must still result in nonsense. And those who insist that the evidence to support complementary and alternative medicine can legitimately be softer than in mainstream medicine will have to reconsider their position. Double standards in medicine existed for many years; undoubtedly they still exist today, but hopefully their days are numbered.

The lack of evidence plagues large sections of complementary and alternative medicine. For a few treatments, however, our knowledge is sufficiently advanced to allow preliminary risk benefit analyses (see table 1). In some cases (for example, ginkgo biloba for intermittent claudication) the balance is positive8; in other instances (for example, chelation therapy for intermittent claudication) it is negative.5 This underscores the point made earlier: generalisations are not possible, and those who offer them must be listened to with scepticism.

The principle of “net benefit” should also include costs. Complementary and alternative medicine is not cheap. Extrapolation from the results of the telephone survey,14 suggests that Britain's annual expenditure is around £1.6 billion, and providers' fees are considerable (table 2).22 But costs must not be viewed in isolation; the real question is whether the use of complementary and alternative medicine increases or decreases overall expenditure in our healthcare system. To answer it, one would require reliable cost evaluation studies. Few such investigations are available to date, the most rigorous of which negate the hypothesis that use of complementary and alternative medicine reduces overall expenditure.23

Table 2.

Average fees (£) charged by providers of complementary and alternative medicine in south west London (1995)*

| Type of treatment | Fee for 1st visit | Fee for follow up visits |

|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture | 35.0 | 20.0 |

| Chiropractic | 37.0 | 16.5 |

| Homoeopathy | 40.0 | 20.0 |

| Osteopathy | 19.5 | 18.0 |

Median duration varied from 30 min (chiropractic) to 90 min (homoeopathy) for 1st visit and from 15 min (chiropractic) to 60 min (acupuncture) for second visit.

Association with powerful non-specific effects

It has been pointed out repeatedly that complementary and alternative medicine can be “ineffective” (in the sense of not being better than a placebo) and still do a world of good to the wellbeing of our patients.24 Some argue that complementary and alternative medicine should be used regardless of the results of placebo controlled clinical trials, particularly when its use is not associated with serious risks (see table 1). In such cases, rigorous research could even be seen as counterproductive. We might, for instance, find little “hard” evidence in favour of aromatherapy; if its “ineffectiveness” became known its availability would decrease, and yet aromatherapy could considerably help patients through its non-specific effects.24

Such arguments cannot be used against the rigorous investigation of complementary and alternative medicine. If research really showed that aromatherapy has no adverse effects and helps people through powerful non-specific (placebo) effects, the medical community should start seriously considering the power of placebos. The research question then shifts to how non-specific effects might be optimised so that more patients (not just those seeing an aromatherapist) can profit from them. Even in this (worst case) scenario, research would yield clinically valuable information.

Conclusion

We should listen less to the opinions of those who either overtly promote or stubbornly reject complementary and alternative medicine without acceptable evidence. The many patients who use complementary and alternative medicine deserve better. Patients and healthcare providers need to know which forms are safe and effective. Its future should (and hopefully will) be determined by unbiased scientific evaluation.

Figure.

One year prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine in various countries. Data based on surveys of random or representative samples of population

Acknowledgments

This is an edited version of a presentation at the the Millennium Festival of Medicine in London, 6-10 November 2000.

Based on a presentation from the Millennium Festival of Medicine

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Ernst E, Resch KL, Mills S, Hill R, Mitchell A, Willoughby M, et al. Complementary medicine—a definition. Br J Gen Pract. 1995;45:506. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezzo J, Berman B, Hadhazy VA, Jadad JR, Lao L, Singh BB. Is acupuncture effective for the treatment of chronic pain? A systematic review. Pain. 2000;86:217–225. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee A, Done ML. The use of non-pharmacologic techniques to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1362–1369. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199906000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooke B, Ernst E. Aromatherapy: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:493–496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernst E. Chelation therapy for peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Circulation. 1997;96:1031–1033. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bronford G. Spinal manipulation. Current state of research and its indications. Neurol Clin North Am. 1999;17:91–111. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams JW, Mulrow CD, Chiquette E, Noël PH, Aguilar C, Cornell J. A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: evidence report summary. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:743–756. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pittler MH, Ernst E. Ginkgo biloba extract for the treatment of intermittent claudication: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med. 2000;108:226–281. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linde K, Claudius N, Ramirez G, Melchart D, Eitel F, Hedges LV, et al. Are the clinical effects of homoeopathy placebo effects? A meta-analysis of placebo controlled trials. Lancet. 1997;350:834–843. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst E. Iridology—not useful and potentially harmful. Arch Opthalmol. 2000;118:120–121. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernst E. Massage therapy for low pack pain: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:65–69. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astin JA, Harkness E, Ernst E. The efficacy of “distant healing”: a systematic review of randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:903–910. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-11-200006060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst E, Köder K. An overview of reflexology. Eur J Gen Pract. 1997;3:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst E, White A. The BBC survey of complementary medicine use in the UK. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst E, Weihmayr T. UK and German media differ over complementary medicine. BMJ. 2000;321:707. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernst E. Alternative views on alternative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:229–230. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vickers A, Cassileth B, Ernst E, Fisher P, Goldman P, Jonas W, et al. How should we research unconventional therapies? A report from the conference on complementary and alternative medicine research methodology, National Institute of Health. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1997;13:111–121. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300010278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ernst E. Funding research into complementary medicine: the situation in Britain. Complement Ther Med. 1999;7:250–253. doi: 10.1016/s0965-2299(99)80011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst E, ed. Complementary and alternative medicine. A desk top reference. London: Mosby (in press).

- 20.Linde K, Jobst K, Panton J Cochrane Collaboration, editors. Cochrane Library. Issue 3. Oxford: Update Software; 1997. Acupuncture for the treatment of bronchial asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linde K, Jobst KA Cochrane Collaboration, editors. Cochrane Library. Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software; 2000. Homeopathy for chronic asthma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White AR, Resch KL, Ernst E. A survey of complementary practitioners' fees, practice, and attitudes to working within the National Health Service. Complement Ther Med. 1997;5:210–214. [Google Scholar]

- 23.White AR, Ernst E. Economic analysis of complementary medicine: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8:111–118. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2000.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vickers A. Why aromatherapy works (even if it doesn't) and why we need less research. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:444–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]