Rapidly growing cities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America are often seen as presenting among the world's most intractable problems in terms of improving health. This is especially so their for low income citizens, whose tenements and squatter settlements are among the world's most life threatening living and working environments. Rapid urbanisation may even be considered to be “a problem.” But rapid urbanisation is usually associated with economic success. Furthermore, an increasing concentration of people in urban areas lowers unit costs for many forms of infrastructure and services that improve health. I have summarised key trends in urban change and some of the opportunities provided for improving health within an urbanising population. I have also highlighted how it is the quality of governance at city and municipal level that determines whether these opportunities are realised.1

Summary points

Most of the 300 cities with populations over 1 million are in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and many have populations that have grown more than tenfold since 1950, but most urban dwellers live in cities with populations under 50 000

The largest cities are concentrated in the largest economies, and many smaller cities have been able to attract an important proportion of new investment

The concentration of people in cities provides opportunities for improving health and environmental quality; the resulting economies of proximity greatly reduce unit costs

The absence of effective and representative government exacerbates urban environmental health problems

An urbanising world

More than two thirds of the world's urban population is now in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Since 1950, the urban population of these regions has grown more than fivefold. Rapid urban growth has also brought a huge increase in the number of large cities, including many that have reached sizes that are historically unprecedented. Just two centuries ago, there were only two “million cities” worldwide (that is, cities with one million or more inhabitants)—London and Beijing (Peking). By 1950, there were 80; today there are over 300. Most of these million cities are in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and many have populations that have grown more than tenfold since 1950. Brasilia, the federal capital of Brazil, did not exist in 1950 and now has more than 2 million inhabitants.

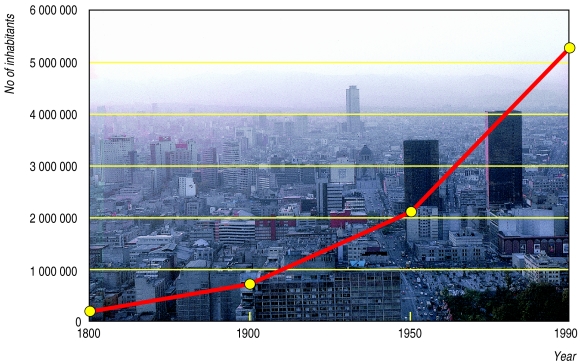

“Mega-cities,” with ten or more million inhabitants are a new phenomenon. The first city to reach this size was New York in around 1940. There were 12 mega-cities by 1990 (the latest year for which there are relatively accurate statistics as data for 2000 censuses are not available or censuses are scheduled for 2001); seven were in Asia, three in Latin America, and two in the United States. In 1800, the average size of the world's 100 largest cities was fewer than 200 000 inhabitants but now it is over 5 million. These statistics give the impression of rapid urbanisation that is primarily focused on large cities. But this is not the case.

Most of the urban population lives outside large cities

Most urban dwellers in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (and in other regions) live in urban areas with fewer than one million inhabitants; many live in small market towns or administrative centres with under 50 000. Mega-cities with 10 million or more inhabitants had less than 3% of the world's population in 1990 and most such cities had slow population growth rates for the last decade for which there are census data. According to the latest UN statistics more than half the world's population still lives in rural areas, and the world's urban population will come to exceed its rural population only around 2007.2

Most of the world's largest cities are considerably smaller by the year 2000 than had been expected. Various factors help to explain this. One key reason has been slow economic growth (or economic decline), so fewer people moved there. Another reason has been the capacity of smaller cities to attract an important proportion of new investment. In the many nations that have had effective decentralisation, urban authorities in smaller cities have more resources and more capacity to compete for new investment. Trade liberalisation and a greater emphasis on exports have also increased the comparative advantage of many smaller cities, and advances in transport and communications have lessened the advantages for businesses of locating in the largest cities.

Fertility rates have come down more than expected. There are still large cities where population growth rates have remained high in the past 20 years—for instance, Dhaka (Bangladesh) and many cities in India and China—and strong economic performance by such cities is the most important factor in explaining this. China has many examples of cities with rapid population growth rates, which is hardly surprising, given the nation's rapid economic growth sustained over the past two decades. In other regions, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, there are also some cities whose population was much increased by the movement there of people displaced by wars, civil strife, or drought, but this is usually a temporary movement, not a permanent one.

Associations between economic growth and urban change

Most nations with rapid increases in their level of urbanisation (the proportion of their population living in urban areas) are also nations with rapid economic growth.3 Large cities develop only where there are successful economies or high concentrations of political power. Within Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the largest cities are concentrated in the largest economies: Brazil and Mexico in Latin America, and China, India, Indonesia, and the Republic of Korea in Asia. In 1990 these nations contained all but one of the mega-cities and nearly half of all the million cities. Despite the speed of change in urban populations, there is a (perhaps surprising) continuity in the location of important urban centres. Most of the largest urban centres in Latin America, Asia, and North Africa today have been important urban centres for centuries.

Beyond a rural-urban divide

Perhaps too much emphasis is given to the fact that the world is becoming predominantly urban. One reason for this is imprecision in defining urban and rural populations. There are large differences in the urban definitions used by governments, so one nation's urban population can be all those living in settlements with 20 000 or more inhabitants while another's is all those living in settlements with 1000 or more inhabitants. Comparison of these two nations' levels of urbanisation is particularly inaccurate if a large section of the population lives in settlements of between 1000 and 19 999 inhabitants (which is the case in many nations). Any nation can increase or decrease its level of urbanisation simply by changing its definition of urban. India would be predominantly urban if it used the urban definition of Sweden or Peru. Thus, the world's urbanisation level is best considered not as a precise percentage (for instance, 47% in 2000) but as being between 40% and 55%, depending on the definition used for urban centres.

Too little attention is also given to the economic and political transformations that have underpinned urbanisation. The distinction between rural and urban populations can highlight differences in economic structure, population concentration, and political status (as virtually all local governments are located in urban centres) but it is imprecise. In many nations, large sections of the rural population work in non-agricultural activities or commute to urban areas. Many urban centres also have a considerable proportion of their workforce in agriculture or providing goods or services for agricultural populations. In addition, discussing rural and urban areas separately forgets the multiple flows between them in terms of (among other things) people, goods, income, capital, and information.4 Many low income households draw goods or income from urban and rural sources. Distinctions between rural and urban areas are also becoming almost obsolete in and around many major cities as economic activity spreads outwards—for instance, around Jakarta, Bangkok, Mumbai (and the corridor linking it to Pune), the Pearl River Delta in China, and the Red River Delta in Vietnam.5,6

An uncertain urban future

Most publications discussing urban change predict that the world will continue to urbanise far into the future. Such projections should be viewed with caution. A steady increase in urbanisation among low income nations is likely to occur only if they also have steadily growing economies. While we should hope that lower income nations achieve more buoyant economies, the current prospects for most of them are hardly encouraging, with political instability, civil war, and large debt burdens.

There are also grounds for doubting whether a large proportion of the world's population will ever live in very large cities. In stagnant economies, urbanisation levels do not increase much. In successful economies much new investment is going to small or medium sized cities. In regions with advanced transport and communications systems, rural inhabitants and enterprises can enjoy standards of infrastructure and services and access to information that historically have been available only in urban areas. Thus, both low and high income nations may have smaller than expected increases in the populations of their cities, although for very different reasons.

The opportunities provided by cities

Although the concentration of people and production in cities is usually considered a problem, this also provides many potential opportunities for improving health and environmental quality. This concentration provides economies of proximity which greatly reduce unit costs (see box).

Unit costs that may be reduced in cities through economies of scale and proximity

Piped water

Sewers

Drains

All weather roads

Footpaths

Electricity

Rubbish collection

Public transport

Health care

Schools, preschool centres, and child development centres

Emergency services (fire fighting and emergency medical services)

Enforcement of regulations on occupational health and pollution control

Specialised services and waste handling

Tax collection and charges

Even in overcrowded tenements and illegal settlements, the densities are rarely too high to pose problems for the cost effective provision of infrastructure and services. The concentration of people in cities makes it easier to involve them in electing governments at local and city level and in taking an active part in decisions and actions within their own district or neighbourhood.

Some infrastructure and service costs may rise with city size, especially those in which the costs of acquiring land for their provision is a considerable part of total cost. Labour costs may also be higher. The need for more complex and sophisticated pollution controls may also rise. But in discussing the economies of scale, proximity, and agglomeration, it is important to be clear as to who benefits from these (and who does not). Private enterprises benefit from many of these economies; one major reason why they choose to concentrate in urban areas is because it lowers their production costs. But part of this may arise from their capacity to negotiate a highly subsidised infrastructure and services or other subsidies. Part of their cost reductions may arise from their ability to pay below subsistence wages or to externalise costs—to the detriment of their workforce (substandard occupational health and safety standards) or wider populations (through inadequate pollution control and waste management).

Cities may be considered to be particularly vulnerable to disasters, but there are also economies of scale for reducing many risks—for instance, in the per capita cost of measures to lessen the risks, reduce the risks when they occur, and respond rapidly and effectively when a disaster is imminent or happens. In the absence of good management, however, cities can be particularly hazardous as large low income settlements develop in hazardous sites because no other sites are available to them and as the needed prevention, mitigation, and response measures are not taken.

Thus, the main issue in regard to an urbanising world is not the problems provided by a more urbanised population but the failure to develop urban governments that can make use of the opportunities. Only in the absence of effective and representative government, including the institutional means to ensure provision of an infrastructure and services and the control of pollution, are urban environmental health problems greatly exacerbated. Some cities show how much can be achieved. People in the city of Porto Alegre in Brazil, famous for its participatory budgeting (which allow citizens to influence public investment priorities in their neighbourhood) have a life expectancy of 76 years.7 Small cities such as Ilo in Peru and Manizales in Colombia have shown how much local initiatives can improve health and living standards.8,9 Thus, governments and international agencies should look more to the opportunities provided by an urbanising world to improve health and to the institutional means needed to ensure this happens.

Figure.

LIBA TAYLOR/PANOS

Average size of the world's 100 largest cities

Acknowledgments

This is an edited version of a presentation at the Millennium Festival of Medicine in London, 6-10 November 2000.

Based on a presentation from the Millennium Festival of Medicine

References

- 1.Hardoy JE, Mitlin D, Satterthwaite D. Environmental problems in an urbanizing world: local solutions for city problems in Africa, Asia and Latin America. London: Earthscan Publications (in press).

- 2.United Nations. New York: Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2000. World urbanization prospects: the 1999 revision. (ESA/P/WP.161). [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations Centre for Human Settlements. An urbanizing world: global report on human settlements, 1996. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tacoli C. Bridging the Divide: Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies. London: IIED Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Programme; 1998. (Gatekeeper Series No 77). [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGee TG. Urbanization or Kotadesasi—the emergence of new regions of economic interaction in Asia. Honolulu: East West Center; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Bank. Entering the 21st Century: world development report 1999/2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menegat R. Atlas ambiental de Porto Alegre. Porto Alegre: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Alegre, and Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Follegatti JLL. Ilo: a city in transformation. Environment and Urbanization. 1998;11/2:181–202. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velasquez LS. Agenda 21; a form of joint environmental management in Manizales, Colombia. Environment and Urbanization. 1998;10/2:9–36. [Google Scholar]