Abstract

Background

Emerging evidence suggests that there is an increase in healthcare utilization (HCU) in patients due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). We investigated the change in HCU pre and post hospitalization among patients discharged home from COVID-19 hospitalization for up to 9 months of follow up.

Study design and methods

This retrospective study from a United States cohort used Optum® de-identified Clinformatics Data Mart; it included adults discharged home post hospitalization with primary diagnosis of COVID-19 between April 2020 and March 2021. We evaluated HCU of patients 9 months pre and post -discharge from index hospitalization. We defined HCU as emergency department (ED), inpatient, outpatient (office), rehabilitation/skilled nursing facility (SNF), telemedicine visits, and length of stay, expressed as number of visits per 10,000 person-days.

Results

We identified 63,161 patients discharged home after COVID-19 hospitalization. The cohort of patients was mostly white (58.8%) and women (53.7%), with mean age 72.4 (SD± 12) years. These patients were significantly more likely to have increased HCU in the 9 months post hospitalization compared to the 9 months prior. Patients had a 47%, 67%, 65%, and 51% increased risk of ED (rate ratio 1.47; 95% CI 1.45–1.49; p < .0001), rehabilitation (rate ratio 1.67; 95% CI 1.61–1.73; p < .0001), office (rate ratio1.65; 95% CI 1.64–1.65; p < .0001), and telemedicine visits (rate ratio 1.5; 95% CI 1.48–1.54; p < .0001), respectively. We also found significantly different rates of HCU for women compared to men (women have higher risk of ED, rehabilitation, and telemedicine visits but a lower risk of inpatient visits, length of stay, and office visits than men) and for patients who received care in the intensive care unit (ICU) vs those who did not (ICU patients had increased risk of ED, inpatient, office, and telemedicine visits and longer length of stay but a lower risk of rehabilitation visits). Outpatient (office) visits were the highest healthcare service utilized post discharge (64.5% increase). Finally, the risk of having an outpatient visit to any of the specialties studied significantly increased post discharge. Interestingly, the risk of requiring a visit to pulmonary medicine was the highest amongst the specialties studied (rate ratio 3.35, 95% CI 3.26–3.45, p < .0001).

Conclusion

HCU was higher after index hospitalization compared to 9 months prior among patients discharged home post-COVID-19 hospitalization. The increases in HCU may be driven by those patients who received care in the ICU.

Introduction

Most patients are discharged alive from hospitalization due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). With over 6 million COVID-19 hospitalizations in the United States (US), there is growing concern regarding the health care utilization (HCU) of patients post discharge [1–4]. Prior reports of non-COVID-19 patients show high HCU post hospitalization and post care in an intensive care unit (ICU) [5–8]. Based on this evidence, HCU is expected to be high for patients discharged from COVID-19 admission.

Overall, studies have found that patients who tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-COV-2) have greater HCU than patients who tested negative [9, 10]. Also, the 30-day and 60-day readmission rate for patients discharged alive after a hospitalization due to COVID has been reported as 13% to 24% and 19.9%, respectively [2, 11–17]. Similarly, the rates of ambulatory visits, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospitalizations vary following discharge from COVID-19 in socially disadvantaged patients compared to those who are socially advantaged [18, 19]. It has been reported that 82.1% of patients had follow-up visits with a primary care provider in the 60 days following discharge from COVID-19 hospitalization [20]. However, these observations were obtained from cohorts of patients who were ambulatory and/or post-hospital discharge. The HCU of patients discharged home post-COVID-19 hospitalization is not well understood. We, therefore, investigated the HCU of patients discharged home from COVID-19 hospitalization for 9 months post-discharge, using a national US database. We hypothesized that HCU will be high post discharge and that certain specialties will see a disproportionate increase in their share of post-discharge HCU. Some of the results of this study were previously presented in the form of a conference abstract [21].

Study design and methods

Data source

We used de-identified data from Optum’s Clinformatics Data Mart (CDM), a database of administrative health claims for members of large commercial and Medicare Advantage health plans. Optum’s CDM is a comprehensive database that includes claims from enrollees with either commercial insurance or Medicare Advantage Plans, encompassing over 63 million unique enrollees across the United States from all states. Notably, more than 95% of the enrollees in Optum’s CDM possess commercial insurance. This database does not include traditional Medicare or Medicaid enrollees, implying a potential underrepresentation of the older or low socioeconomic status populations. A significant aspect of the data from Optum’s CDM is its source diversity; since the data originates from insurance claims. This inclusivity means data can come from a variety of healthcare settings, whether rural or urban, academic or community-based. Whenever a CDM patient files a claim with their insurance, this information is captured in the database, regardless of the specific medical center or office they visited. This wide-ranging data collection provides a broad and diverse view of healthcare utilization and patterns across different demographics and geographies in the United States. The University of Texas Medical Branch Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study (IRB# 20–0180). The need for informed consent was waived by the IRB due to the de-identified nature of the study.

Cohort selection

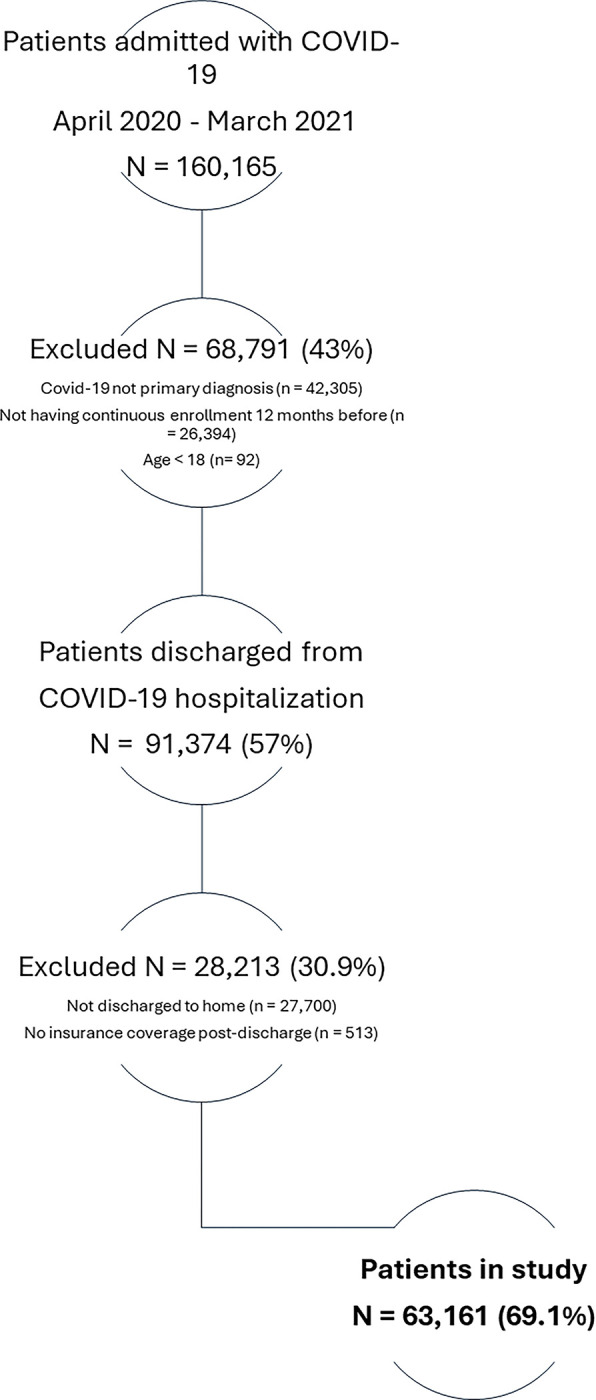

Our sample included all adults hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19 who were discharged home (with or without home health care) between April 2020 and March 2021, with at least 12 months of continuous enrollment before this diagnosis. COVID-19 cases were identified by the International Classification for Diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis code U07.1 or from a positive test. We excluded patients who were not discharged home or whose insurance coverage ended during the inpatient stay (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Cohort selection of patients discharged from COVID-19 hospitalization.

COVID-19 was identified by the ICD-10-CM diagnosis code U07.1 or from a positive test. Patients were excluded if they were not discharged home or if their insurance coverage ended during the inpatient stay. Abbreviations: COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; Optum CDM: Optum’s Clinformatics Data Mart. ICD-10-CM: International Classification for Diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification.

Variables

We collected information on patient demographics: age at time of COVID-19 diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, and region of residence. We identified comorbidities by ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes, with a 12-month lookback period before COVID-19 hospitalization.

We evaluated HCU in the 9 months pre and post hospitalization from COVID-19. We divided the study period into pre-COVID-19 hospitalization (-0-9 months) and post-COVID-19 discharge (+0–9 months). We also subdivided into 3-month periods for pre-COVID-19 hospitalization (-0-3 months, -3-6 months, and -6-9 months before hospitalization) and post-COVID-19 discharge (+0–3 months, +3–6 months, and +6–9 months post discharge). HCU included ED visits, inpatient admissions, rehabilitation/skilled nursing facility (SNF) admissions, outpatient visits, and telemedicine visits. Based on billing information, we examined outpatient visits (from here on out referred to as office visits) to primary care providers, including family medicine, internal medicine, and nurse practitioner visits, and certain sub-specialties, such as cardiology, pulmonary medicine, endocrinology, neurology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychiatry, and other mental health professionals.

Statistical analysis

Cohort characteristics are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range, or frequency and percentage. HCU in the pre-COVID-19 hospitalization and post-COVID-19 discharge periods was expressed as the number of visits per 10,000 (10k) person-days, where each patient contributed person-days until death, loss of insurance eligibility, or the end of the 9-month follow-up period. To identify the risk of HCU post-COVID-19 compared to pre-COVID-19 hospitalization incidence rate ratios (number of observed events over total person-days contributed) and exact Poisson confidence intervals were calculated for each period [22]. All findings were considered statistically significant if the P value was <0.05. To address the concern of survivor bias, the study required participants to have at least 12 months of data prior to their primary COVID-related hospitalization for accurate comorbidity assessment, without mandating post-hospitalization follow-up, and utilized a person-days approach to accommodate variable follow-up durations. As a sensitivity analysis, we evaluated HCU post discharge in women and compared it to that of men. In addition, we analyzed HCU in patients who received care in the ICU and compared it to those who did not. We also examined the distribution of office visits per 10K person-days by provider specialty (select specialties) in each period and calculated rate ratios to identify the risk of having a visit with that specialist post-COVID-19 hospitalization compared to the pre-hospitalization period. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary NC).

Results

In this retrospective study, we identified 63,161 patients discharged home after hospitalization due to COVID-19. This cohort was comprised of patients who were mostly white (58.8%), women (53.7%), and with mean age of 72.4 (SD± 12.8) years. The most common comorbidities of these patients were hypertension (75.8%), diabetes mellitus (36.5%), congestive heart failure (25.8%), coronary artery disease (25.2%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (23%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients discharged home from COVID-19 hospitalization from April 2020 to March 2021 in the United States.

| Characteristics | N = 63,161 (100%)a,b,c |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 72.4 (12.8) |

| Sex | - |

| Women | 33897 (53.7) |

| Men | 29263 (46.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity d,e | - |

| White | 37135 (58.8) |

| Hispanic | 9843 (15.6) |

| Black | 10443 (16.5) |

| Asian | 1473 (2.3) |

| Other/Unknown | 4261 (6.8) |

| Region | - |

| Midwest | 13897 (22) |

| Northeast | 8465 (13.4) |

| South | 30145 (47.7) |

| West | 9299 (14.7) |

| Unknown | 1355 (2.1) |

| Comorbidities | - |

| DM | 23,065 (36.5) |

| HTN | 47,890 (75.8) |

| Asthma | 6,285 (10.0) |

| COPD | 14,534 (23.0) |

| CKD | 6,793 (10.8) |

| ESRD | 2,032 (3.2) |

| Stroke | 5,547 (8.8) |

| CHF | 16,303 (25.8) |

| Cancer | 7,982 (12.6) |

| CAD | 15,925 (25.2) |

| Liver disease | 3,871 (6.1) |

| ICU use | 21760 (34.5) |

a Our cohort consists of 63,161 patients discharged home after hospitalization due to COVID-19.

b COVID-19 and comorbidities were identified by ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes(S7 Table in S1 File).

c Patients were excluded if they were not discharged home or if their insurance coverage ended during the inpatient stay.

d Patients self-identifying as non-Hispanic ethnicity were categorized based on race (White, Black, Asian, other/unknown).

e Patients self-identifying as Hispanic ethnicity were included in the Hispanic group regardless of race.

Definition of abbreviations: COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; SD: Standard Deviation; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; HTN: Hypertension; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; ESRD: End-Stage Renal Disease; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; ICD-10-CM International Classification for Diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification.

Health care utilization after discharge home from hospitalization due to COVID-19

Patients discharged home from COVID-19 hospitalization were significantly more likely to have increased HCU in the 9 months post hospitalization compared to the 9 months prior to such hospitalization (Tables 2, 3, S1-S6, S8 Tables in S1 File). For example, these patients had 47%, 67%, 65%, and 51% increased risk of ED (rate ratio 1.47; 95% CI 1.45–1.49; p < .0001), rehabilitation (rate ratio 1.67; 95% CI 1.61–1.73; p < .0001), office (rate ratio1.65; 95% CI 1.64–1.65; p < .0001), and telemedicine visits (rate ratio 1.5; 95% CI 1.48–1.54; p < .0001), respectively. Also, the post-discharge risk of inpatient visits (rate ratio 2.20; 95% CI 2.14–2.25; p < .0001) and longer length of stay (rate ratio 2.62; 95% CI 2.59–2.64; p < .0001) doubled compared to the pre-COVID-19 hospitalization period (Table 2 and S1 Table in S1 File).

Table 2. Health care utilization of patients pre and post-hospitalization due to COVID-19,c,d,e.

| - | Pre-COVID-19 Hospitalization a,b | Post-COVID-19 Hospitalization a,b | - | - | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | -0-9 months | +0–9 months | Percent change c | Rate ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

| ED visits | 22.0 | 32.3 | 47.0 | 1.47 (1.45–1.49) | < .0001 |

| Inpatient visits | 7.0 | 15.4 | 119.6 | 2.20 (2.14–2.25) | < .0001 |

| Inpatient admission (LOS)d | 42.7 | 111.6 | 161.6 | 2.62 (2.59–2.64) | < .0001 |

| Rehabilitation visits | 3.3 | 5.5 | 66.7 | 1.67 (1.61–1.73) | < .0001 |

| Office visits | 156.5 | 257.5 | 64.5 | 1.65 (1.64–1.65) | < .0001 |

| Telemedicine visits | 11.2 | 17.0 | 51.3 | 1.51 (1.48–1.54) | < .0001 |

a Our cohort consists of 63,161 patients discharged home after hospitalization due to COVID-19.

b Health care utilization of patients, measured by number of visits per 10k person-days.

c Percent change of HCU pre- and post- hospitalization due to COVID-19.

d LOS was defined as the number of days of inpatient status after hospital admission.

Definition of abbreviations: COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; ED: Emergency Department; ICD-10-CM: International Classification for Diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification; LOS: length of stay. 10k = 10,000

Table 3. Health care utilization of patients pre and post hospitalization due to COVID-19,, by medical specialty.

| Pre-COVID-19 Hospitalizationa,b | Post-COVID-19 Hospitalizationa,b | - | - | - | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -0-9 months | +0–9 months | Percent change c | Rate ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| PCP | 78.8 | 133.1 | 68.9 | 1.69 (1.67–1.70) | < .0001 |

| Cardiology | 12.2 | 21.9 | 79.2 | 1.79 (1.76–1.83) | < .0001 |

| Pulmonary Medicine | 3.8 | 12.9 | 235.5 | 3.35 (3.26–3.45) | < .0001 |

| Endocrinology | 2.3 | 3.7 | 63.8 | 1.64 (1.57–1.71) | < .0001 |

| Neurology | 3.0 | 4.5 | 51.6 | 1.51 (1.46–1.58) | < .0001 |

| Phys Med & Rehab | 2.0 | 2.5 | 25.8 | 1.26 (1.20–1.32) | < .0001 |

| Psychiatry | 1.9 | 2.7 | 41.4 | 1.41 (1.35–1.49) | < .0001 |

| Mental Health Professional | 0.8 | 1.3 | 66.1 | 1.66 (1.54–1.79) | < .0001 |

a Our cohort consists of 63,161 patients discharged home after hospitalization due to COVID-19.

b Health care utilization of patients, measured by number of visits per 10k person-days.

c Percent change of HCU from pre- to post-hospitalization periods due to COVID-19.

Definition of abbreviations: HCU: health care utilization; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; PCP: Primary Care Provider; ICD-10-CM: International Classification for Diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification; Phys Med & Rehab: Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; 10k = 10,000.

As a sensitivity analysis, we evaluated HCU post discharge in women and compared it to that of men patients (S5 Table in S1 File). We also analyzed HCU in patients who received care in the ICU and compared it to those who did not (S6 Table in S1 File). We found that women have higher risk of ED (rate ratio 1.03; 95% CI 1.01–1.05), rehabilitation (rate ratio 1.23; 95% CI 1.17–1.30), and telemedicine visits (rate ratio 1.12; 95% CI 1.1–1.16) than men. But women have a lower risk of inpatient visits (Rate ratio 0.91, 95% CI 0.88–0.94), and office visits (rate ratio 0.92; 95% CI 0.91–0.93) than men. Additionally, women had a shorter length of stay (rate ratio 0.84, 95% CI 0.84–0.86) (S5 Table in S1 File).

Compared to patients who did not receive ICU care, those who were admitted to the ICU have increased risk of ED visits (19%, rate ratio 1.19; 95% CI 1.17–1.22), inpatient visits (27%, rate ratio 1.27; 95% CI 1.23–1.31); shorter length of stay (34%, rate ratio 1.34; 95% CI 1.32–1.35), office visits (46%, rate ratio 1.46; 95% CI1.44–1.47), and telemedicine visits (38%, rate ratio 1.38; 95%1.35–1.43).

Contrary to the elevated risks stated above, patients discharged home from COVID-19 hospitalization who received care in the ICU were less likely to have rehabilitation visits (rate ratio 0.92; 95% CI 0.87–0.97) compared to those who did not receive care in the ICU (S6 Table in S1 File).

Outpatient office visits were the most utilized health care service by patients post discharge (275.5 visits-10k person-days). All included specialties showed more visits in the 9 months after discharge than in the 9 months prior to hospitalization. Primary care providers had the highest number of visits post discharge (133.1 visits/10k persons-days), followed by cardiology (21.9 visits/10k persons-days) and pulmonary medicine (12.9 visits/10k persons-days). Interestingly, pulmonary medicine saw the highest percent change in the number of pre- (3.8 visits/10k person-days) vs post-discharge visits (235.5% change). Similarly, the risk of having a visit to any specialty significantly increased post discharge, but the risk of having a visit with pulmonary medicine was the highest (rate ratio 3.35, 95% CI 3.26–3.45, p < .0001) (Table 3, S3, S4 Tables in S1 File).

We also found that the risk of having visits with neurology (rate ratio 1.51; 95% CI 1.46–1.58; p < .0001), psychiatry (rate ratio 1.41; 1.35–1.49; p<0.0001) and other mental health professionals (rate ratio 1.66; 95% CI 1.54–1.79; p<0.0001) significantly increased post discharge compared to the pre-hospitalization period (Table 3).

Discussion

In our retrospective cohort study of patients discharged home after a COVID-19 hospitalization in the US, we found that these patients have an increased risk of post-discharge HCU compared to the pre-hospitalization period. Our results are similar to studies of HCU in patients post discharge from non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 admissions [3]. Our findings advance the knowledge about HCU post-COVID hospitalization in patients discharged home. Additionally, our observations of different HCU in women compared to men and in those who received care in the ICU compared to those who did not may help health systems and policy makers identify potential disparities and at-risk populations who may benefit from targeted interventions to improve their HCU post discharge. Furthermore, we found that all medical specialties studied had high use that varied by specialty, which can help us identify medical providers needed to meet patient care demands during the next respiratory pandemic.

We must consider why patients discharged home from a hospitalization for severe COVID-19 have high HCU. Acute infection by SARS-COV-2, leading to hospitalization due to severe COVID-19, has been associated with conditions that have multi-organ involvement and dysfunction, most commonly pneumonia but also including cardiac injury, acute liver injury, acute kidney injury, venous and arterial thrombotic events, and a variety of neurological and psychiatric manifestations [23]. Multisystem infection of the virus may explain a variety of persistent organ dysfunctions and may result in chronic clinical symptoms [23, 24]. These persistent symptoms likely lead patients to seek medical care post hospitalization and health systems to develop multi-disciplinary clinics, facilitating referrals to multiple specialists [25]. Our findings of increase in post-discharge HCU suggest an increased demand for hospital-centered care.

The differences in HCU in women compared to men are intriguing. Prior literature showed that women had lower risk of adverse outcomes and mortality due to COVID-19 compared to men [26, 27]. In our study, women have higher risk of ED visits, rehabilitation visits, and telemedicine visits, and lower risk of inpatient visits, office visits compared to men. Women also had a shorter length of stay compared to men. Although we do not know why these differences exist, our findings are consistent with prior non-COVID-19 literature of fewer hospital admissions, shorter length of stay, and fewer physician visits in women compared to men [28, 29]. The differences in HCU by sex may be explained by a variety of factors, including demographics and social factors, such as health care needs (limitation in mobility, disability, specific chronic comorbidities) and economic access factors (overall health, income, education, etc.) [30].

Our finding of higher HCU in patients post-discharge home from COVID-19 may be primarily driven by patients who received care in the ICU. Pre-COVID-19, research showed that patients with sepsis, pneumonia, central line associated blood stream infections, and ventilator associated pneumonia had increased post-discharge mortality and high HCU [8]. Also, patients who receive prolonged mechanical ventilation (>21 days) have high risk of mortality, readmissions to the hospital and ICU, and high HCU [5]. Finally, patients who survive ARDS have impaired functional status, and their quality of life is affected even 2 years after discharge from the ICU [7]. In our cohort, 34.5% of patients received care in the ICU, which is in accordance to published findings that nearly 1 in 3 (33%) hospitalized patients with COVID-19 develop ARDs and 1 in 4 hospitalized patients require transfer to the ICU (26%) [31]. We also know that patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU have longer length of stay in the hospital and ICU, longer length of mechanical ventilation, and therefore may be at increased risk of nosocomial infections [32, 33]. If we are to extrapolate those percentages to the over 6 million people hospitalized due to COVID 19, it may be expected that over 1.5 million people may experience the elevated HCU described in our study.

Notable insights emerged from our study regarding medical specialty utilization post-COVID-19 discharge. Primary care providers and outpatient office visits were pivotal, while an intriguing surge in pulmonology clinic visits highlighted disproportionate escalating demand for specialized respiratory care. This may be explained by the persistent pulmonary symptoms and complications post-COVID-19. A recent study highlighted the multisystemic impact of COVID-19 and reported that the chronic symptoms linked with SARS-CoV-2 infection involved a variety of organ systems, with chronic cough notably identified as one of the defining symptoms for the new diagnosis of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PACS) [34]. Another study found that SARS-COV-2 infection was associated with an additional 213 health care visits per 1000 patients during the 6 months after the acute stage of illness [8]. Notably, this study found the second highest increase in utilization was observed for pulmonary symptoms (bronchitis, venous thromboembolism, dyspnea upon exertion, hypoxemia, and cough). Another study in France evaluated sequelae in COVID-19 patients post-hospital discharge from March to May 2020. They found that 51% of patients reported persistent respiratory symptoms 4 months after COVID-19 hospitalization. This study found persistent ground glass opacities in 32%, fibrotic lung lesions in 12%, and abnormal diffusion capacity in 13.6% of patients 4 months post-discharge [35]. Other studies have reported persistent reductions in diffusion capacity 3 months to 4 months after acute illness, with rates ranging from 16.4% to 52% [4, 36]. Multivariate analysis studies also found that severe disease during acute illness was associated with a persistently reduced diffusion capacity [36] and worse heart function [24]. Additionally, the most frequent serious manifestation of acute COVID-19 infection is pneumonia [37], with a reported 17% of patients complicated with acute respiratory distress syndrome [38]. All of the above may help explain our finding of 235.5% change in pulmonary visits from the pre- to the post-hospitalization period.

Interestingly, studies have reported persistent pulmonary symptoms in patients without persistent physiologic impairments [39, 40]. One study aimed to investigate the long-term pulmonary effects of severe COVID-19 pneumonia by assessing cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) performance in 60 patients 12 months after a COVID-19 infection that required ICU management [41]. Exercise capacity assessed by CPET was within normal limits in most patients 12 months after hospitalization, and impairment was predominantly related to persistent deconditioning or prior respiratory comorbidities. Complementing our findings, other studies have compared hospitalization related to COVID to other causes of hospitalization.

The disproportionate increases in HCU by PCP and pulmonary specialist may also be explained by the establishment of multi-disciplinary post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) clinics. One study surveyed healthcare systems in the US participating in the PETAL Network and reported that 70% had established an outpatient clinic for PASC with physicians providing care in 97% of clinics supplemented by Advanced Practice Professionals [25]. Of these systems, 21% automatically referred all patients discharged alive post-COVID-19 hospitalization to the PASC clinic for outpatient follow up while 70% of referrals relied on physician discretion or patient requests. Subspecialties available were pulmonary (97%), general medicine and primary care (58%), cardiology (52%), and psychiatry (30%). Remarkably, 73% of these PASC clinics were distinct from their previously established post-ICU clinics [25].

We acknowledge our study’s limitations, including its retrospective design; therefore, we cannot infer cause and effect but only an association between being discharged from a hospitalization due to COVID-19 and an increase in post-discharge HCU. Also, our patient cohort was obtained from a national commercially-insured and Medicare Advantage claims database. Therefore, we do not provide information on uninsured/out of network patients, and this may underrepresent the number of patients discharged home from COVID-19 hospitalizations and their post-discharge HCU. Also, our study period spans the first year of the pandemic when many COVID-19 treatments and vaccines were in development or in early stages of use. Therefore, we are unable to determine how many of our patients were vaccinated or had received COVID-19-specific therapy and how these two factors mediate post-discharge HCU. Also, the mean age of our population is 72 years, and our results may be more representative of the older adult population. Similarly, based on limitations from our dataset, we cannot determine the post-discharge mortality rate in our cohort; however, with an estimated 7.8% all-cause post-discharge mortality rate [42] reported in the literature, we know most patients discharged from a COVID-19 hospitalization are alive one year post-discharge [42]. To address this limitation, our cohort only included patients enrolled in insurance/database until the end of the study period. Therefore, each patient contributed person-days until death, loss of insurance eligibility, or the end of the 9-month follow-up period. Additionally, we acknowledge the multifaceted influences on healthcare utilization, extending beyond direct medical necessity. Integral factors likely include socioeconomic status, health insurance coverage, access to and availability of care, and clinician referrals. We must also consider the potential for bias due to resource exhaustion amid the pandemic’s economic fallout. Resource limitation might have prompted a decrease in healthcare visits despite ongoing health impairments, thereby affecting our analysis of utilization rates.

Our study has several strengths including a cohort of patients discharged home obtained from a database that spans nationally. The information obtained from our study provides insights in the HCU trends post-COVID-19 hospitalization in the US. We were also able to follow patients for a considerable period, up to 9 months post discharge, and to compare pre- and post-COVID hospitalization HCU in the same patient population, eliminating potential selection bias or the influence of such confounders as demographic characteristics and prior comorbidities.

Conclusions and implications

In our nationally representative retrospective study, we identified that HCU remains high among patients discharged to a home setting after a hospitalization due to COVID-19. Health systems and providers may be able to use this information to better deploy resources in the care of this chronically ill population.

Supporting information

The tables and figures included herein offer further insights, data points, and visual representations to enhance the understanding and interpretation of the research presented in the primary manuscript.

(DOCX)

Data Availability

Optum data is proprietary (and we have purchased access to it under contract), therefore, we are not permitted to share the data. We accessed Clinformatics through the university contract. This contract expired on 6/30/2023 To acquire the same type of data, researchers need to sign a contract with Optum. Contact information for Optum: call: 1-866-3061321; email: connected@optum.com The cohort and analytic results can be replicated by following the inclusion/exclusion criteria as described in the manuscript. Interested researchers would need to sign individual contracts with Optum and receive the data. We did not have any special access privileges to Optum data.

Funding Statement

Dr. Puebla Neira reports support from NHLBI Division of Intramural Research (US), NHLBI Advanced Respiratory Research for Equity (AiRE) - AZ-PRIDE Program grant (5R25HL126140-09) during the conduct of this study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers of Disease Control and Prevention COVID Data Tracker: Hospital Admissions [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 11]. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#new-hospital-admissions [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavery AM, Preston LE, Ko JY, Chevinsky JR, DeSisto CL, Pennington AF, et al. Characteristics of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients Discharged and Experiencing Same-Hospital Readmission—United States, March-August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2020. Nov 13 [cited 2023 Jan 20];69(45):1695–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33180754/ doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6945e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koumpias AM, Schwartzman D, Fleming O. Long-haul COVID: healthcare utilization and medical expenditures 6 months post-diagnosis. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2022. Dec 1 [cited 2023 Jun 25];22(1):1–14. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-022-08387-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.miao Zhao Y, min Shang Y, bin Song W, quan Li Q, Xie H, fu Xu Q, et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine [Internet]. 2020. Aug 1 [cited 2022 Sep 11];25:100463. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7361108/ doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill AD, Fowler RA, Burns KEA, Rose L, Pinto RL, Scales DC. Long-Term Outcomes and Health Care Utilization after Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation. Ann Am Thorac Soc [Internet]. 2017. Mar 1 [cited 2023 Aug 16];14(3):355–62. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28033033/ doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-792OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill AD, Fowler RA, Pinto R, Herridge MS, Cuthbertson BH, Scales DC. Long-term outcomes and healthcare utilization following critical illness—a population-based study. Crit Care [Internet]. 2016. Mar 31 [cited 2022 Sep 11];20(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27037030/ doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1248-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Matté A, Barr A, et al. Two-year outcomes, health care use, and costs of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2006. Sep 1 [cited 2023 Aug 16];174(5):538–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16763220/ doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-693OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dick A, Liu H, Zwanziger J, Perencevich E, Furuya EY, Larson E, et al. Long-term survival and healthcare utilization outcomes attributable to sepsis and pneumonia. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2023 Aug 16];12(1):432. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3534544/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tartof SY, Malden DE, Liu ILA, Sy LS, Lewin BJ, Williams JTB, et al. Health Care Utilization in the 6 Months Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2022. Aug 1 [cited 2023 Jan 20];5(8):e2225657–e2225657. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2795163 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.25657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNaughton CD, Austin PC, Sivaswamy A, Fang J, Abdel-Qadir H, Daneman N, et al. Post-acute health care burden after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ [Internet]. 2022. Oct 17 [cited 2023 Jan 20];194(40):E1368–76. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36252983/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAlister FA, Dong Y, Chu A, Wang X, Youngson E, Quinn KL, et al. The risk of death or unplanned readmission after discharge from a COVID-19 hospitalization in Alberta and Ontario. CMAJ [Internet]. 2022. May 16 [cited 2023 Jan 20];194(19):E666–73. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35577377/ doi: 10.1503/cmaj.220272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loo WK, Hasikin K, Suhaimi A, Yee PL, Teo K, Xia K, et al. Systematic Review on COVID-19 Readmission and Risk Factors: Future of Machine Learning in COVID-19 Readmission Studies. Front Public Health. 2022. May 23;10:1311. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.898254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson-Lane SG, Sutton NR, Chubb H, Yeow RY, Mazzara N, DeMarco K, et al. Race, Ethnicity, and 60-Day Outcomes After Hospitalization With COVID-19. J Am Med Dir Assoc [Internet]. 2021. Nov 1 [cited 2023 Jan 20];22(11):2245–50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34716006/ doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gwin M, Saleki M, Lampert H, Meo N, Bann M. Emergency department visits and readmissions after COVID-19 hospitalization: a cross-sectional analysis. Intern Emerg Med [Internet]. 2021. Sep 1 [cited 2023 Jan 20];16(6):1715–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33537919/ doi: 10.1007/s11739-021-02644-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taupin D, Anderson TS, Merchant EA, Kapoor A, Sokol-Hessner L, Yang JJ, et al. Preventability of 30-Day Hospital Revisits Following Admission with COVID-19 at an Academic Medical Center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf [Internet]. 2021. Nov 1 [cited 2023 Jan 20];47(11):696–703. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34548237/ doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donnelly JP, Wang XQ, Iwashyna TJ, Prescott HC. Readmission and Death After Initial Hospital Discharge Among Patients With COVID-19 in a Large Multihospital System. JAMA [Internet]. 2021. Jan 19 [cited 2023 Jan 20];325(3):304–6. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2774380 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atalla E, Kalligeros M, Giampaolo G, Mylona EK, Shehadeh F, Mylonakis E. Readmissions among patients with COVID-19. Int J Clin Pract [Internet]. 2021. Mar 1 [cited 2023 Jan 20];75(3):e13700. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ijcp.13700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Khullar D, Wang F, Steel P, Wu Y, Orlander D, et al. Socioeconomic variation in characteristics, outcomes, and healthcare utilization of COVID-19 patients in New York City. PLoS One. 2021. Jul 1;16(7):e0255171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth SE, Govier DJ, Marsi K, Cohen-Cline H. Differences in Outpatient Health Care Utilization 12 Months after COVID-19 Infection by Race/Ethnicity and Community Social Vulnerability. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2022. Mar 1 [cited 2023 Aug 6];19(6). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8949439/ doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-Day Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2021. Apr 1 [cited 2023 Jan 31];174(4):576–8. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7707210/ doi: 10.7326/M20-5661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaidan MF, Neira DAP, Polychronopoulou E, Nishi SP, Duarte AG, Kuo YF, et al. Health care utilization among patients discharged alive post-COVIDF-19 hospitalization. Chest [Internet]. 2022. Oct [cited 2023 Aug 21];162(4):A519. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9548925/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardeo Sahai, Anwer Khurshid. Statistics in epidemiology: methods, techniques, and applications. 1996;321. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA [Internet]. 2020. Aug 25 [cited 2022 Sep 11];324(8):782–93. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2768391 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2020. Dec 17 [cited 2022 Sep 11];383(25):2451–60. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/ doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2009575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valley TS, Schutz A, Peltan ID, Vranas KC, Mathews KS, Jolley SE, et al. Organization of Outpatient Care After COVID-19 Hospitalization. Chest [Internet]. 2022. Jan 31 [cited 2022 Sep 11];161(6):1485–9. Available from: https://europepmc.org/articles/PMC8801392 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin JM, Bai P, He W, Wu F, Liu XF, Han DM, et al. Gender Differences in Patients With COVID-19: Focus on Severity and Mortality. Front Public Health. 2020. Apr 29;8:545030. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, Albano G, Antonelli M, Bellani G, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 in Intensive Care Units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. 2020. Oct 1 [cited 2023 Aug 19];180(10):1345–55. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32667669/ doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cameron KA, Song J, Manheim LM, Dunlop DD. Gender Disparities in Health and Healthcare Use Among Older Adults. J Womens Health [Internet]. 2010. Sep 1 [cited 2023 Aug 17];19(9):1643. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2965695/ doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lum YS, Chang HJ. The effect of Medicaid coverage on use of health services by low-income elderly people. Soc Work Res [Internet]. 1998. Mar 1 [cited 2023 Aug 19];22(1):31–43. Available from: doi: 10.1093/swr/22.1.31 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danielsen AC, Lee KM, Boulicault M, Rushovich T, Gompers A, Tarrant A, et al. Sex disparities in COVID-19 outcomes in the United States: Quantifying and contextualizing variation. Soc Sci Med. 2022. Feb 1;294:114716. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tzotzos SJ, Fischer B, Fischer H, Zeitlinger M. Incidence of ARDS and outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a global literature survey. Crit Care [Internet]. 2020. Aug 21 [cited 2023 Aug 16];24(1). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7441837/ doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03240-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliveira E, Parikh A, Lopez-Ruiz A, Carrilo M, Goldberg J, Cearras M, et al. ICU outcomes and survival in patients with severe COVID-19 in the largest health care system in central Florida. PLoS One [Internet]. 2021. Mar 1 [cited 2023 Aug 16];16(3):e0249038. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0249038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gendreau S, Benelli B, Delíere M, Tuffet S, de Prost N, Razazi K, et al. Partitioning Mechanical Ventilator Duration in COVID-19-related Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022. Jul 1;206(1):114–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202108-1963LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thaweethai T, Jolley SE, Karlson EW, Levitan EB, Levy B, McComsey GA, et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA [Internet]. 2023. Jun 13 [cited 2023 Aug 16];329(22):1934–46. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2805540 doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.8823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morin L, Savale L, Pham T, Colle R, Figueiredo S, Harrois A, et al. Four-Month Clinical Status of a Cohort of Patients After Hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA [Internet]. 2021. Apr 20 [cited 2022 Sep 11];325(15):1525–34. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33729425/ doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blanco JR, Cobos-Ceballos MJ, Navarro F, Sanjoaquin I, Arnaiz de las Revillas F, Bernal E, et al. Pulmonary long-term consequences of COVID-19 infections after hospital discharge. Clinical Microbiology and Infection [Internet]. 2021. Jun 1 [cited 2022 Sep 11];27(6):892. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7920814/ doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaim S, Chong JH, Sankaranarayanan V, Harky A. COVID-19 and Multiorgan Response. Curr Probl Cardiol [Internet]. 2020. Aug 1 [cited 2022 Sep 9];45(8):100618. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7187881/ doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2020.100618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Qi T, Liu L, Ling Y, Qian Z, Li T, et al. Clinical progression of patients with COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. J Infect [Internet]. 2020. May 1 [cited 2022 Sep 11];80(5):e1–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32171869/ doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gamberini L, Mazzoli CA, Prediletto I, Sintonen H, Scaramuzzo G, Allegri D, et al. Health-related quality of life profiles, trajectories, persistent symptoms and pulmonary function one year after ICU discharge in invasively ventilated COVID-19 patients, a prospective follow-up study. Respir Med [Internet]. 2021. Nov 1 [cited 2023 Jan 21];189. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34717097/ doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scaramuzzo G, Ronzoni L, Campo G, Priani P, Arena C, La Rosa R, et al. Long-term dyspnea, regional ventilation distribution and peripheral lung function in COVID-19 survivors: a 1 year follow up study. BMC Pulm Med [Internet]. 2022. Nov 9 [cited 2023 Jan 21];22(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36352423/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noureddine S, Roux-Claudé P, Laurent L, Ritter O, Dolla P, Karaer S, et al. Evaluation of long-term sequelae by cardiopulmonary exercise testing 12 months after hospitalization for severe COVID-19. BMC Pulm Med [Internet]. 2023. Dec 1 [cited 2023 Jan 21];23(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36635717/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramzi ZS. Hospital readmissions and post-discharge all-cause mortality in COVID-19 recovered patients; A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med [Internet]. 2022. Jan 1 [cited 2023 Jan 23];51:267–79. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34781153/ doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.10.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]