Abstract

Background

There is evidence supporting the value of patient engagement (PE) in research to patients and researchers. However, there is little research evidence on the influence of PE throughout the entire research process as well as the outcomes of research engagement. The purpose of our study is to add to this evidence.

Methods

We used a convergent mixed method design to guide the integration of our survey data and observation data to assess the influence of PE in two groups, comprising patient research partners (PRPs), clinicians, and researchers. A PRP led one group (PLG) and an academic researcher led the other (RLG). Both groups were given the same research question and tasked to design and conduct an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-related patient preference study. We administered validated evaluation tools at three points and observed PE in the two groups conducting the IBD study.

Results

PRPs in both groups took on many operational roles and influenced all stages of the IBD-related qualitative study: launch, design, implementation, and knowledge translation. PRPs provided more clarity on the study design, target population, inclusion–exclusion criteria, data collection approach, and the results. PRPs helped operationalize the project question, develop study material and data collection instruments, collect data, and present the data in a relevant and understandable manner to the patient community. The synergy of collaborative partnership resulted in two projects that were patient-centered, meaningful, understandable, legitimate, rigorous, adaptable, feasible, ethical and transparent, timely, and sustainable.

Conclusion

Collaborative and meaningful engagement of patients and researchers can influence all stages of qualitative research including design and approach, and outputs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40271-024-00685-8.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Although there is evidence that patient engagement in research has value, few studies assess the actual influence of patient engagement at all stages of research. |

| By integrating qualitative and quantitative research findings, we identified patient research partner roles, and their influence on critical activities throughout the research spectrum. |

| Collaborative and meaningful engagement of patients and researchers can influence the research design and approach, and outputs in qualitative research. |

Introduction

Harrington et al. define patient engagement (PE) in research as “the active, meaningful, and collaborative interaction between patients and researchers across all stages of the research process, where research decision making is guided by patients’ contributions as partners, recognizing their specific experiences, values, and expertise” [1]. How patients (including relatives, family caregivers, and public) operate with academic researchers in actual practice varies by the patients’ roles and level of power and decision-making authority [2]. The roles of patients as partners could include involvement in governance, priority setting, developing the research questions, sharing the results with the target audiences, or even performing aspects of the research to ensure that the research being conducted is relevant and valuable to the patients that it affects [3–10]. In this paper, we use the term ‘patient research partner’ (PRP) to define patients who operate as active project members on an equal basis with academic researchers [11].

Several frameworks, guidelines, and resources are available to guide PE activities in research and elucidate the different levels of PE [4, 12–17]. The International Association for Public Participation spectrum of public participation (IAP2) framework is an example of a framework that is used often to describe levels of partnership among researchers, patients, and clinicians [18]. However, it is not clear whether this spectrum accurately reflects patient experiences in research and is a desirable model of engagement in health research from the patient’s perspective [19]. There has also been an increasing number of evaluation frameworks to monitor and evaluate PE in research, such as the Community Engagement and Participation in Research measure, Patients as Partners in Research surveys, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) engagement activity inventory (WE-ENACT), Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool (PPEET) etc. [20], as well as a number of studies reporting the various ways in which patient involvement has made a difference, particularly the value of engagement to the patient or researcher [21, 22]. Fewer studies assess how PE influences the research during the different research stages [2, 23–26] from the perspectives of all members working together on projects using validated evaluation tools or whether there are different study designs, approaches, and outputs based on the roles of PRPs in the research. Few use a mixed method approach. No study uses three evaluation tools together to study PE. Our aim in this exploratory study was to investigate the influence of PE throughout the entire research process (from the launch stage to the knowledge translation stage) and identify the outcomes of research engagement.

Methods

We chose a convergent mixed method design [27] to gather a more comprehensive account of the influence of PE in research and outcomes on the research, drawing upon the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches to address our research question. We selected this design because of the lack of rigorously developed and validated tools specifically designed to evaluate the impact of patient engagement on research, and that have involved patients in their development and reporting [28]. We ensured that our study design met all criteria in the Good Reporting of A Mixed Methods Study (GRAMMS) checklist. Our study aimed to assess the influence of PE throughout the entire research process. Our primary research question was “Do PRPs as study team members make a difference to a research study, and at what stages of the research?” Our quantitative approach looked at the self-perceived influence and process of PE on the research during the different stages while our qualitative approach looked at the critical outcomes of research engagement. We used Dillon’s Critical Outcomes of Research Engagement (CORE) framework during analysis to identify short- and long-term outcomes of engagement [23].

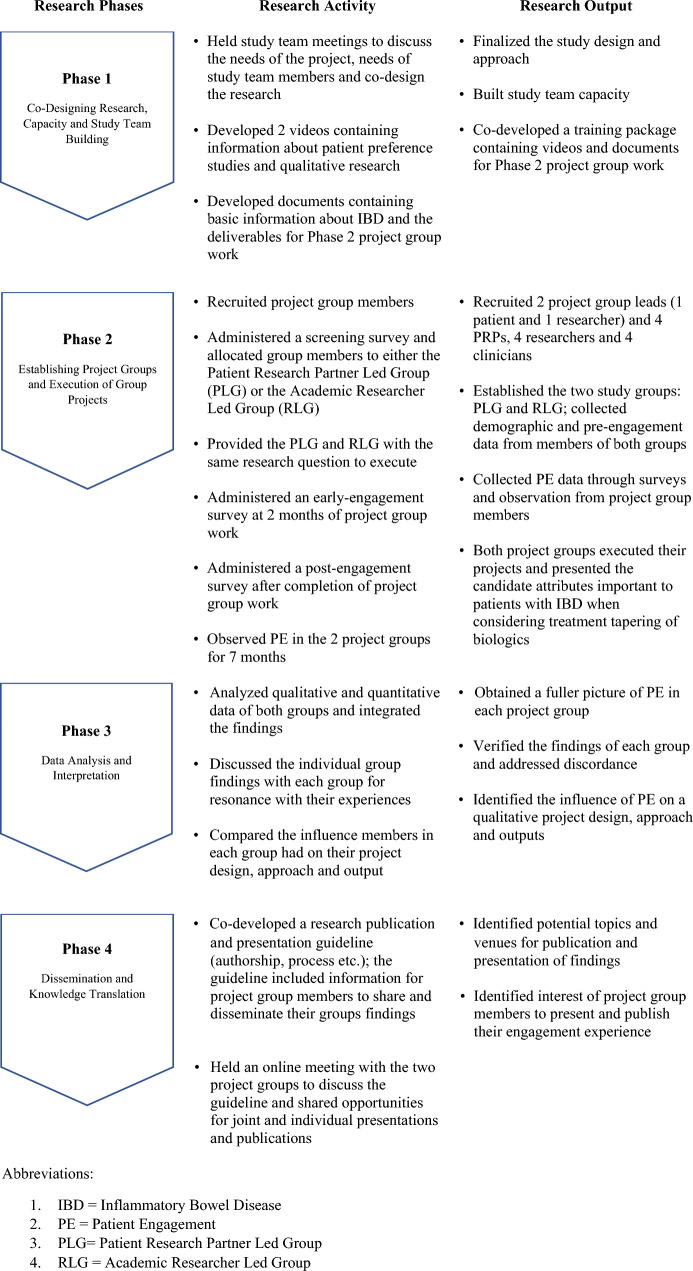

We approached the study in four phases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The four study phases with their respective activities and outputs. IBD inflammatory bowel disease, PE patient engagement, PLG Patient Research Partner-Led Group, RLG Academic Researcher-Led Group

Phase 1: Co-Designing Research, Capacity and Study Team Building

In this phase, the overarching study team comprising researchers, institutional leaders, and a PRP finalized the study goals and objectives, design, and the data collection approach. We also developed a training package for our study participants containing information about patient preference studies (PPS), qualitative research, and basic information about the Phase 2 project group work and deliverables.

Phase 2: Establishing Project Groups and Execution of Group Projects

We established two project groups, a PRP-led group (PLG) and an academic researcher-led group (RLG). Each group had two PRPs, two researchers and two clinicians. Our reasoning for two groups was to acknowledge that both researchers and patients can lead research.

Recruitment of Group Members

Outreach to potential project group members occurred through our professional contacts, and through provincial and national networks such as the SPOR IMAGINE (Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research–Inflammation, Microbiome, and Alimentation: Gastro-Intestinal and Neuropsychiatric Effects) Network [29], the Alberta Health Services Digestive Health Strategic Clinical Network (DHSCN), and the Alberta and British Columbia SPOR SUPPORT (Support for People and Patient-Oriented Research and Trials) Units between Fall 2020 and Spring 2021. The study research coordinators sent study flyers to their contacts and mentioned networks requesting them to disseminate this information to potential participants through their organization’s website and by email. Interested patients then contacted the coordinators for more information about the study. We used a maximum variation purposive sampling strategy [30] to recruit PRPs and convenience sampling [30, 31] to recruit clinicians and researchers. PRP participants were purposively selected based on their qualitative research experience and knowledge and training in POR. Table 1 outlines the eligibility criteria for each type of group member. We provided all group members, including the two group leads, an honorarium as per the CIHR guidelines of $25 per hour [32].

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria of project group members

| PRPs |

• Currently taking or took some treatment for chronic digestive conditions such as IBD • Currently participating or had participated in a project or initiative in health care • Had received patient-oriented research (POR) training • Based in Canada • Willing to make the time commitment |

| PRP lead |

• Familiarity with or interest in digestive health research • Had received POR training • Based in Canada • Had experience independently leading/facilitating all aspects of qualitative research activities • Willing to make the time commitment |

| Academic researchers |

• Had some knowledge about qualitative research • Had interest in POR or digestive health research • Based in Canada • Willing to make the time commitment |

| Academic researcher lead |

• Postgraduate degree with some qualitative research training • Familiarity with or interest in digestive health research • Based in Canada • Had experience independently leading/facilitating all aspects of qualitative research activities • Willing to make the time commitment |

| Clinicians |

• Gastroenterologists or non-physician healthcare providers such as IBD nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists • Based in Canada • Willing to make the time commitment |

IBD inflammatory bowel disease, POR patient-oriented research, PRP patient research partner

Group Allocation

We administered a screening survey prior to the group work to purposively place the recruited members in a group to ensure that both groups were matched as much as possible. The screening survey contained items from the Patient Centered Outcome Research Institute’s Ways of Engaging–ENgagement ACtivity Tool (WE-ENACT) [33, 34]. WE-ENACT allows for modifications of questions and selection or deletion of items to capture stakeholder experience in the engagement. The items used for placing PRPs in their groups included years of qualitative experience and involvement in POR, experience leading POR projects, graduate of the Patient and Community Engagement Research (PaCER) program [35] and some demographic items. The PLG and RLG leads did not have access to the screening survey responses to avoid any unconscious bias that might affect PE during the group work.

Project Group Work

Each project group was tasked with conducting a qualitative patient preference research project independently within a period of 7 months. We selected inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) as the project topic as PRP involvement in qualitative research in this area is considered good research practice [36]. Both groups were provided with the same research question: “What factors or attributes are important to patients with IBD in considering treatment tapering of biologics?”, and were asked to design and conduct a study addressing this question.

Data Collection from Group Members

We collected quantitative data through surveys [41] and qualitative data through observation [40] to address the gaps in the survey data. Our observation data augmented our understanding of what the survey numbers truly mean, including their implications. Qualitative and quantitative data collection was carried out in a similar timeframe, but independent of each other. Equal importance was given to both types of data in answering our study objective.

Members from both groups completed surveys administered at two timepoints: 2 months into the project (early engagement) and at the end of the project (post-engagement). The early-engagement survey contained items from the WE-ENACT tool [33]. The post-engagement survey contained items from three tools: The Patient Engagement in Research Scale-22 (PEIRS-22) [28], the Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool (PPEET-Version 2) [37], and the WE-ENACT. PIERS-22 is a scale that captures the quality or degree of meaningful patient engagement in a project while PPEET-2 captures the participants’ assessments of the key features of the engagement initiative.

Together, the three tools measured the roles of project group members and their perceived influence and impact on the critical activities—the processes and outputs of the qualitative IBD study, as well as the levels of meaningful engagement in the two groups. Participants provided information about their general experience (whether they felt trust, honesty, shared learning, etc.), how convenient it was for them to work on the project, the support they received, the benefits of their involvement, and how satisfied they were with the initiative. We complemented the survey data collection with observation [38–41] of PE in the two groups. Due to COVID-19 and the different locations of the project group members, observation was undertaken online and included the collection of descriptive information (factual data of online discussions and chats), and reflective information (thoughts, ideas, and questions). One qualified study team member was attached to each group to observe and document stakeholder roles and influence during the qualitative study. A third staff performed oversight of this work to ensure quality data collection. The two observers (NS and KB), one for each group, were trained prior to data collection by a staff member well versed in the observation technique. We used a semi-structured guide as a template for documenting the observations (refer to Marshall et al. [40] for the guide). The observation data enabled us to explore the critical outcomes of research engagement in the two groups. Together with the survey data, we were able to understand the influence of PE on the research design, process, approach, and outputs and the impact on the research.

We received ethics approval from the University of Calgary [REB20-1563] and the University of British Columbia [H20-03385] to conduct this study and for the groups to conduct their qualitative projects.

Phase 3: Data Analysis and Interpretation

Data analysis occurred after the data collection process was completed. The two forms of data were analyzed separately and then merged.

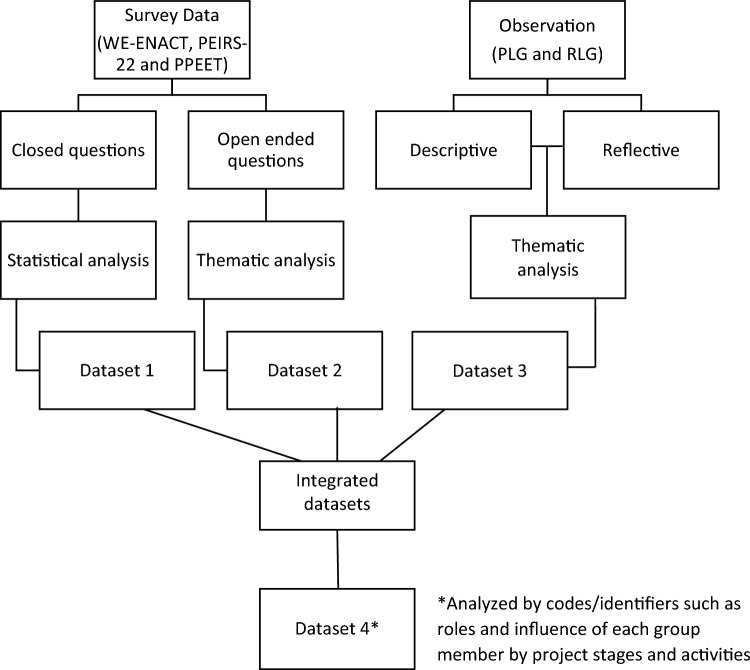

For each group, we completed the statistical and textual analysis of the survey data (datasets 1 and 2) and the textual analysis of the observation data (dataset 3), separately (Fig. 2). We calculated the frequencies for each level of the Likert scale items for the PPEET and the WE-ENACT items and the PEIRS-22 single construct called meaningful engagement in research [28]. We coded the open-ended questions in our survey data into themes using deductive and inductive codes.

Fig. 2.

Data analysis. PEIRS-22 Patient Engagement in Research Scale-22, PLG Patient Research Partner-Led Group, PPEET Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool, RLG Academic Researcher-Led Group, WE-ENACT Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) engagement activity inventory

We thematically coded the observation data using NVivo-12 [42] by project stages and activities and by the 11 CORE items [23] (patient-centered, meaningful, team collaboration, understandable, rigorous, integrity and adaptable, legitimate, feasible, ethical and transparent, timely, and sustainable). We created ‘journey maps’ for PRPs, clinicians, and researchers to see how they influenced the project at each project stage and activity [40]. The journey maps gave us an understanding of each participant’s role and their influence to accomplish the group project’s goal. We integrated the findings of the three datasets (dataset 4) by codes/identifiers such as roles of each group member at each project stage and activity. We compared and contrasted the results looking at the complementary and diverse aspects of the influence of PE at each research stage, specifically on the design, approach, and outputs in the two groups. We looked to see how the findings complemented, corroborated, and contradicted each other. We addressed any discordance in our findings during the member check-in exercise with both groups after the discussions. Our integrated approach thus provided a more holistic understanding of PE driven by a framework. The analysis was conducted by two study team members (NS, KB). A third team member (GM) checked the coding and analysis of the observation data.

Phase 4: Dissemination and Knowledge Translation

We created a research publication and presentation guideline (authorship, process etc.) and shared this document with the group members during a workshop. We also discussed opportunities for joint and individual presentations. This discussion resulted in one group agreeing to consider publishing their reflections about working on the project.

PRP Involvement

A PRP with IBD lived experience and an extensive background of training and involvement in POR [35, 43, 44] collaborated with the study team in multiple ways from developing the research question and study design through to reviewing this manuscript critically. We held an online meeting to discuss the results and outcomes of PE with members of both groups. The group PRPs were also involved in all the stages and critical tasks of their respective qualitative projects.

Results

Characteristics of Group Participants

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the group participants. From the 29 eligible participants, 14 consented (48% participation) and were placed in a group. Workload issues and health concerns were the most common reasons eligible participants declined participation. Both groups had participants who they had worked with earlier on other projects or were professionally acquainted. Our team felt that it was important to gather this information as group member familiarity could impact collaboration and teamwork which in turn could influence the results of our study. One PRP in the RLG withdrew during the project design stage (retention rate of 93%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of group participants (n = 14)

| Characteristics | PRP (n = 5) | Researcher (n = 5) | Clinician (n = 4) | All (n = 14) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLG (n = 3) | RLG (n = 2) | PLG (n = 2) | RLG (n = 3) | PLG (n = 2) | RLG (n = 2) | ||

| Age, 35+ years (n) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

| Gender, woman (n) | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 10 |

| Gender, man (n) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Ethnicity (n) | |||||||

| White (European, North American) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Others (Asian-South, Middle Eastern | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Educational attainment (n) | |||||||

| Undergraduate | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Graduate/professional or doctorate level | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 12 |

| Years involved in patient-oriented research (n) | |||||||

| < 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| > 12 months | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Years know/worked with your group members? (n) | |||||||

| < 1 year | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| > 1 year | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

PLG patient research partner-led group, RLG academic researcher-led group

PRPs in both groups had either received PaCER training delivered by University of Calgary Continuing Education [35, 43, 44] or had gained qualitative research expertise through their education and previous jobs. Most of the researchers, including the academic researcher lead, had limited knowledge of IBD. Two researchers and two clinicians were involved in patient-oriented research (POR) for < 1 year.

Roles and Influence of PE by Project Stages and Critical Activities Including Design, Approach and Output

What PRPs, researchers, and clinicians did, and how they influenced the project is described below by the research stages, and summarized in Tables 3a, 3b, 3c, and 3d. The critical outcomes of research engagement are also highlighted in these tables for each stage. We present the collective results of both groups and individual group results where possible, protecting participants’ confidentiality.

Table 3a.

Influence of patient engagement during the launch stage

| PE in the launch stage (role of stakeholders during this stage) | Influence of PE on the research (impact on the research) | Critical Outcomes of Research Engagement (CORE) framework themes |

|---|---|---|

|

All members in both groups shared their research interests, skills, and strengths. The PLG members also shared their availability to work on the project. Members in the PLG agreed to their roles and project plan while members in the RLG did not formally attest the plan “In terms of my own experiences so as a researcher I’ve been involved in multiple different research projects both stemming from both that are quantitative and qualitative in nature, and as a patient I was actually diagnosed with (XX) in (Year)… so with the facilitation of focus groups I think that would be great because then all of us are coming from a patient perspective yeah so, that's good, I like that decision” PRP |

Having a clear plan and roles on the project held members accountable, created an open and transparent process of working together and enabled the group to establish a good working relationship, express their views freely, and move the project forward in a timely manner. Being accountable resulted in continued participation on the project. Not having formal roles resulted in PRPs feeling “less engaged” on the project and was one of the contributing factors to the withdrawal of one PRP at a later stage from the study “I believe (by sharing interests and experience) we started to have a good working relationship and to understand how each of us can have the best impact on the study.” PRP “(splitting up tasks based on individuals’ capacity and strengths within the team) allowed members to focus on their tasks and contribute meaningfully to the work, and allowed us to complete it (the project) on time.” PRP |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Team collaboration (4) Sustainable |

PE patient engagement, PLG patient research partner-led group, PRP patient research partner, RLG academic researcher-led group

Table 3b.

Influence of patient engagement in the design stage

| PE in the design stage (role of stakeholders during this stage) | Influence of PE on the research (impact on the research) | Critical Outcomes of Research Engagement (CORE) framework themes |

|---|---|---|

|

PRPs in both groups shared their lived experience, questions and concerns “I think as a recipient of biologic treatment my question is, do I have to take this forever? Are there other options? What does it look like when tapering off? What do I need to know to make me feel comfortable that I can actually make a decision?” PRP |

The diverse PRPs’ lived experience helped gain a deeper understanding about tapering of biologics, and what was important to consider while designing and conducting the study from a patient perspective “I think this (patient lived experience) has helped to shed light on the patient perspective and potentially tailor study design and approach in a patient-focused way.” PRP “Provided a starting point for our discussions as a group, as well as guided us in preparing the interview/focus group guides.” PRP |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Legitimate |

|

Both groups’ members operationalized ‘tapering’ for their qualitative group project “I asked how we are defining 'tapering' and described the various types of tapering I am familiar with (as a patient with IBD) and that we would need to be sure we define what we mean by tapering. I also suggested that, in my experience, tapering is generally not supported by IBD care teams due to insufficient research.” PRP |

Discussions about the research question resulted in developing a patient-friendly project title and design/approach that was rigorous, resonated with the patient experience and aligned with the purpose of the study. Group members obtained more clarity on the target study population to include in the qualitative study design, and the approach to capture attributes relevant to the community. It also enabled the development of the project materials “Doing so (defining the question) enabled us to develop project materials much more easily, as we had a specific goal to work towards.” PRP “I just wanted to chime in from a patient perspective, I think this title works in terms of just capturing what we want, and that is people that are on biologics. This title is very user friendly, you have people who are happy and biologics, and you put them in a situation where you ask them about it and they can start thinking about it for the future.” PRP “I think (defining the question), this helped the team focus on some of the nuances patients may experience when contemplating the tapering question. Our team decided to complete a literature review to better understand the topic and what research is already out there.” PRP |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Team collaboration (4) Understandable (5) Rigorous (6) Integrity/adaptable (7) Legitimate |

|

All group members in both groups discussed and determined the study design and approach “I really like the idea of looking at both clinician and patient perspectives because I think clinicians will have certain attributes that are important in their mind and patients will have different ones and combining both of those types of information might make it more successful to like attempt tapering in the future, like if clinicians can buy in and there's a study saying here's what clinicians said was important here's what patients said is important and then move forward like that I think it'd be great contribution.” PRP “Exploring the ‘why’ aspect is super important because, if it's just because they heard from a neighbor or a friend, that this is a poison that they're getting, maybe then it's better to sort of clarify the myth or because people are snowbirds and they're on IV therapy and they want to go down to the States.” Clinician |

Collaborative decisions regarding the study design and approach including the inclusion–exclusion criteria, and how to approach data collection (where not to collect data, what data to collect and from whom) resulted in an evidence-based, rigorous, feasible, and ethical design and approach that was relevant, meaningful, and aimed to benefit the end-users; patients, families, and the broader community “(Collaborative decision making) ensured that the research conducted was evidence-based and follows standards, while taking patient needs into consideration.” Researcher “(Decision making with PRPs) has helped the team get on the same page towards figuring out recruitment, study design and be aware of potential pitfalls (e.g. potential issues with recruiting from gastroenterologists’ clinics)” PRP “Participating in conversations that focused on defining the inclusion criteria, and conversations about overall project plan, made sure we were consistent, and helped us to minimize biases.” Researcher |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Team collaboration (4) Understandable (5) Rigorous (6) Integrity/adaptable (7) Legitimate (8) Feasible (9) Ethical and transparent (10) Timely |

|

The PRP Lead and the PRPs in the RLG were engaged in the literature review and received some training in the nuances of a rapid review. The researchers led this activity. Clinicians provided directions on what literature to look for and where and shared some articles “(Name of the researcher) and I reviewed the search information and determined that we have the articles that we need to collate and identify the attributes for the interview guides.” PRP “So, let's say I’ve been on ANT-TNF for five years, I feel good, everything's good, my disease is under control, what's the likelihood that I will stop and restart, that I am going to develop antibodies. I’m not sure if we have that information, it might be better, you know to look at the rheumatology literature, because you know they more commonly start and stop you know Anti TNFs.” Clinician |

The joint literature review ensured the inclusion of the patient-elucidated terms in the search; in producing results in a lay language, and in a greater understanding of the patient lived experience that was used to design the study in the RLG and to develop appropriate guides, and analytical templates in the PLG “I think we all learned a lot about the topic, although the clinical articles seemed to reinforce the dominant concern that tapering of biologics is not a viable option in patients with IBD.” PRP “helped guide focus groups discussions.” Researcher “The attributes that were identified in the literature search were the foundation of the framework analysis template we used to begin the process of analysis.” PRP |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Team collaboration (4) Understandable (5) Rigorous (6) Legitimate |

|

All the study materials including data collection tools were developed by the PRP lead and PRPs in the PLG, while some of the study materials including data collection tools were developed by the PRPs and some by the researchers in the RLG. “I assisted in the development of the focus group and interview guides, and helped designing the recruitment flyer. I also contributed to reviewing and revising study materials as needed.” PRP “I volunteered to work on the interview guide, as it is my main area of experience. Others worked on and shared recruitment materials…” Researcher |

Engagement of PRP in developing/reviewing the study materials ensured that these were appropriate for a diverse patient group, user friendly (increased readability), ethical and transparent, easy to administer, and effective during data collection “As a facilitator for the upcoming focus groups and interviews, it makes it easier to conduct these processes when I have been involved in planning for them.” PRP “... in response to concerns in the group we tried to create wording which would not imply that the idea of tapering as a treatment was endorsed or supported by the group…” Researcher “Hopefully made the recruitment material stronger.” PRP |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Understandable (4) Legitimate (5) Ethical and transparent |

PE Patient engagement, PLG patient research partner-led group, PRP patient research partner, RLG academic researcher-led group

Table 3c.

Influence of patient engagement in the implementation stage

| PE in the implementation stage (role of stakeholders during this stage) | Influence of PE on the research (impact on the research) | Critical Outcomes of Research Engagement (CORE) framework themes |

|---|---|---|

|

PRPs in both groups provided insight into networks and leveraged their connections to recruit participants. The PLG lead recruited all group study participants. The recruitment of clinician participants was done by the PRPs, and patient participants by the researchers in the RLG “I managed the recruiting process through channels that were identified by team members - email contact, screening calls, communicating with patient channels etc.” PRP |

PRP involvement in recruitment contributed to the improved and timely recruitment of diverse study participants and completion of the study within the stipulated timeframe in the PLG “We were able to find enough participants that satisfied the requirements for diversity of perspective and data saturation.” PRP “I was able to leverage established relationships from others (groups) and recruit the required number of participants” PRP “Assisted in meeting our recruitment targets.” Researcher |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Team collaboration (4) Integrity/adaptable (5) Legitimate (6) Feasible (7) Ethical and transparent (8) Timely |

|

PRPs in the PLG collected all the data while PRPs in the RLG collected data from all clinician participants and researchers collected data from all patient participants. The PRP was provided training in data collection PRPs in both groups continuously checked the assumptions of research team members during this process “Supported group members in collecting data by providing clarification, helping to trouble-shoot issues …” Researcher “Conducted 1 focus group session, and 4 interviews with participants” PRP |

PRP involvement in data collection contributed to meaningful, safe, respectful data collection, and more honest data Training in data collection gave the PRPs more clarity on the research process and enabled active and meaningful engagement on the project “Helped patients feel comfortable and at ease to share information with us.” PRP “I believe I was able to ask relevant questions during data collection.” PRP “This resulted in the collection data outlining the patient's perspectives.” Researcher |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Team collaboration (4) Legitimate (5) Ethical and transparent (6) Timely |

|

Data analysis in the PLG was conducted by the PRP lead and a researcher, while data analysis in the RLG was conducted by the researchers with input from the PRP “I worked together with a researcher to identify themes that emerged from the data. We collaboratively sorted and refined the themes and identified attributes by alternating coding and then reviewing together.” PRP |

The joint analysis exercise helped ensure nothing was missed or mis-represented, and included the patient perspective “I was able to clarify some of the responses in the transcripts to be appropriately coded.” PRP “That's really interesting because from the patient perspective. I mean, I would think that (cost) would be the main theme, not just like a kind of a bucketed other.” PRP “I hope that this contributes to interrater reliability related to the qualitative analysis.” Researcher |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Team collaboration (4) Rigorous (5) Integrity/adaptable (6) Legitimate (7) Timely |

|

All members in both groups were involved in the interpretation of the findings The PRP lead influenced the way the final attributes were presented. This was not the case in the RLG “I think about I’m coming from the perspective of thinking about if I was the patient filling out a discrete choice, things like treatment associated hazards and all of that wouldn't necessarily mean as much to me as if it was put in just plain language.” PRP “I reviewed the final results from the focus group/interviews.” Researcher |

Reviewing the results helped ensure that nothing was missed, and the context of research and statements was appropriate. It also produced new topics for research from the patient perspective and discussions about knowledge translation. The PLG presented their attributes in patient-friendly language, while the RLG used clinician/researcher-friendly language “(Reviewing the results helped in) ensuring context of research and statements was appropriate.” Researcher “it’s clear that people want more education and support.…for knowledge translation and again, these were just some things that really stood out to me was tools that the gastroenterologist could use to be able to communicate to patients when they're in the clinic. ….” PRP |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Team collaboration (4) Understandable (5) Legitimate (6) Sustainable |

PE patient engagement, PLG PRP-led group, PRP patient research partner, RLG academic researcher-led group

Table 3d.

Influence of patient engagement in the knowledge translation stage

| PE in the knowledge translation stage (role of stakeholders during this stage) | Influence of PE on the research (impact on the research) | Critical Outcomes of Research Engagement (CORE) framework themes |

|---|---|---|

|

Project group members attended a meeting to discuss publications and presentation of study findings “I'm just thinking like we have the one conference; the integrated care conference now happens annually. Is this something that could be brought there because there's attended by a variety of different health professionals and maybe it might spark some conversation?” PRP |

Discussion on KT resulted in proposing strategies that promote patient-clinician discussions around treatment tapering One group agreed to think about publishing their reflections on their engagement experiences “Just one idea regarding KT, perhaps a decision-making tree/tool for patients could be helpful, derived from the attributes we’ve determined in the research.” Clinician |

(1) Patient-centered (2) Meaningful (3) Team collaboration (4) Legitimate (5) Sustainable |

KT knowledge translation, PE patient engagement, PRP patient research partner

There was active and meaningful interaction between members in both groups. PRPs in both groups were part of the decision-making process in many critical activities across all stages of the group projects. We identified discordance between the number of roles one PRP reported in the surveys compared with the number determined through observation. Two of the three PRPs, including the PLG lead, influenced many project activities “a great deal or moderately”. The PRP in the RLG influenced the question, design, literature review, and data collection a “great deal or moderately” and a “small amount” in the other critical tasks. Clinicians and researchers in the RLG influenced more activities “a great deal or moderately” than those in the PLG group. The researchers in both groups influenced the study design, literature review, and analysis. The clinicians provided their clinical expertise and influenced the literature review. Both the leads had a considerable influence on each critical activity except in capacity building of group members.

Launch Stage

The launch stage involved getting to know each other, working together, and sharing experiences to help the group understand what information patients need (Table 3a). The roles of the researchers and PRPs in both groups at this stage were mainly advisory. Group leads set up discussions to get insights into the group’s experiences, research interests, and skills. This provided a context to plan and discuss group member roles and develop a “working together” plan in the PLG. The RLG had a working plan, but roles were not formally assigned. Group members volunteered to participate in research tasks on an ad hoc basis, resulting in some members in this group feeling “less engaged” on the project. In contrast, knowing their roles and attending weekly meetings kept group members in the PLG accountable, created a transparent process, and proved to be an efficient way for continued participation, and making timely progress on the project. Other studies have also pointed out that a clear patient engagement plan is a successful engagement approach in health research [16, 45].

Design Stage

The design stage involved refining the research question, designing the study, conducting the literature review, and developing the study material (Table 3b). Both groups had productive conversations around the word ‘tapering’ within the research question. The PRPs used their lived experience to help operationalize this word for the qualitative projects. Collaboratively, all members participated in decisions regarding the project title, the target population, and the design and approach for the qualitative project. Not all member ideas were accepted if the group felt that the quality of the project would be compromised and/or if there was not a clear rationale and/or if the idea affected the project timelines. As an example, a group member proposed collecting additional data through patient blogs which was respectfully discussed but vetoed due to time and resource constraints.

There was a clear shared understanding and agreement of the final design and approach in the PLG, while opinions differed regarding the study design and approach in the RLG. The final decision was not attested by all PRPs in this group with the PRPs influencing the group to conduct a literature review first during this stage. The RLG study design was a rapid literature review followed by interviews of IBD patients residing in Canada who had been or were taking biologics, and clinicians who were practicing in Canada with an interest or specialization in IBD. The PLG study design was an unstructured focus group conducted simultaneously with a rapid literature review, followed by one-on-one interviews with IBD patients residing in Canada who were on biologics.

The PRP lead participated in the literature review in the PLG, provided search terms, and reviewed and extracted data, while a PRP in the RLG suggested, reviewed and extracted data from some papers. The researchers were active players in this critical activity. The clinicians provided directions on what literature to look for and where, and they also shared some papers. The final review results were described in simple, plain language by the PRP lead for the ease and understanding of all group members. Group members specified that the literature review reiterated what the PRPs discussed regarding biologic treatments and shed additional light on some of the nuances that patients may perceive when contemplating the tapering question. PRP participation also helped ensure the inclusion of the patient-elucidated terms in the search.

All the study materials were developed by the PRP lead and PRPs in the PLG, while some of the study materials such as the group project recruitment flyer, demographic questionnaire, and the clinician interview guide were developed by a PRP in the RLG, with the remaining materials developed by the RLG researchers. The written material shared at the meeting was presented in patient-friendly language and in a format that worked best for the PRPs in the groups. For example, PRPs in the PLG received lay summaries of DCEs, qualitative research, and results of the literature reviews to support better participation and decision making. Group members indicated that development of study materials by PRPs formed a roadmap to execute the project in alignment with the research question. PRPs were able to tailor the format and language of the study materials for the diverse group of qualitative study participants. They were also able to ensure that the materials were ethical, transparent, and easier to administer during data collection.

PLG group members indicated that PRP insights during this design phase provided their group more clarity on what is important to an IBD patient, the challenges of stopping biologics, and the pitfalls to avoid while designing the project. The group was able to decide on the inclusion–exclusion criteria, and how to approach data collection. One PRP indicated that these conversations helped them develop appropriate data collection guides and improve the quality of data collected.

Implementation Stage

The implementation stage involved recruitment, data collection, and analysis (Table 3c). PRPs in the PLG managed all recruitment and data collection. The PRP lead was the contact person for recruitment and consent of study participants. The structure of the focus group, the sample size, timing, and roles of each PRP during the interviews were decided by the PRPs and shared with other members in this group. The researchers shared the study flyers with their contacts. In the RLG, a PRP managed the recruitment, consent and interviews of clinician participants, while researchers managed the recruitment, consent and interviews of patient participants. A researcher in the group trained the PRP in data collection. PRPs from both groups provided insights into networks and leveraged established relationships with other patient and clinical groups in the system to help with recruitment. Reflexivity was part of the qualitative data collection and analysis process in both groups, with the interviewers debriefing to discuss their reflections. The PRPs continuously checked the assumptions of research team members during the data collection process.

The recruitment and data collection process of both groups incorporated strategies that showed respect for participant diversity. Both groups used purposive sampling and screened interested participants to achieve a diverse sample of research participants. Interviews were arranged on dates and times suitable to both the study participants and group members conducting the interviews. Consent was truly informed. Both groups followed data privacy guidelines and stored and worked on their project data through a secure folder hosted on a university server. Members in both groups supported and appreciated the patient partners in the groups. For example, one of the researchers offered to be a standby in case the patient partners conducting the interviews felt overwhelmed or burdened.

PE in this stage helped the PLG meet its recruitment target and complete data collection satisfying the requirements for diversity of perspective and data saturation. Eleven patients were recruited and interviewed. The RLG recruited and interviewed three clinicians and two patients. The patient sample size was not realized due to delays in “taking off” including ethics approval. PRPs in both groups indicated that they were able to use their skills and experience more meaningfully and ask relevant questions during the interviews. One felt that their role as a facilitator made project participants comfortable and at ease to share information.

Data analysis was conducted by the PRP lead and a researcher in the PLG. In the RLG, data analysis was carried out by the researchers from that group with input from the PRPs on the clinician data. The analyzed data were shared with all group members in both groups iteratively as it was being coded. PRPs’ involvement in data analysis and interpretation helped identify new codes, ensured the patient voice was not missed or mis-represented during coding, and helped clarify some of the responses that were not fully captured in the transcripts. The discussions also produced new topics for research. One member indicated that the discussions increased their understanding of qualitative research methods.

The PLG identified 11 candidate attributes (outputs of the project), while the RLG identified 21 candidate attributes. Both groups generated attributes related to both the process of treatment tapering and the outcomes of tapering. The PLG identified more outcome-oriented attributes and the RLG more process-oriented attributes. Some unique attributes were identified by each group; in the PLG these were impact on mental health and impact on pregnancy or fertility. In the RLG these were presence of antibodies against current biologic medication and type of IBD/location of disease. Similar attributes were side effects and financial cost of the medication. The lead in the PLG influenced the way the final attributes were presented, with the group describing their attributes using patient‐friendly language. The RLG presented their attributes using more research/clinical terms.

Knowledge Translation Stage

The knowledge translation stage involved explaining or applying results to a real-world setting and sharing study findings (Table 3d). Members from both groups participated in a knowledge translation meeting to discuss the research publication and presentation plan. Possible platforms for presenting the results, including journals, were discussed. The PLG offered to discuss publishing reflections on their engagement experience.

Group Member’s Overall Experience and Value of Engagement

Most members in the PLG (6/7) and the RLG (3/5) either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they were better informed about research as a result of their participation. All seven PLG members and three RLG members reported overall satisfaction with the engagement initiative and reported that the work was a good use of their time. Six PLG members and three RLG members also indicated that they felt trust, honesty, transparency, shared learning, and give and take relationships, “a great deal” or “somewhat” on their projects.

The PEIRS scale overall group score in the PLG was over 82.7, meaning that the quality of engagement of the members on this project was either “extremely meaningful” or “very meaningful”. The overall group score of meaningful engagement in the RLG was slightly over the cutoff point for deficient engagement (< 70.1) with only one member in this group indicating a “moderately meaningful” engagement. The experience of these participants was not as rewarding, as reflected by two domains on the scale: Team Environment and Interaction (6.0/6.4 cutoff) and Benefits (9.2/9.6 cutoff). Not having a clear idea of the research question; not having team members with clear responsibilities at the start; and failing to complete the group work on time due to many obstacles were some factors that contributed to the “unrewarding” experience in this group.

Both PRPs and researchers perceived an added value from the collaborative work increasing the likelihood of a change in perception of power dynamics in health care research and future collaboration. PRPs indicated that working on the group project provided them the opportunity to work with new colleagues from across the country, build new relationships and learn more about IBD and research. Clinicians and researchers also learned a lot from this experience and found the process “dynamic” and “valuable”. The biggest barrier encountered was the lack of “time” and “understanding” of the overall research objective.

Discussion

Over the last 10 years, researchers have been engaging with PRPs in different roles across the research spectrum, with roles generally limited to the preliminary research activities [45, 46]. The influence of the engagement has also been increasingly assessed with some studies presenting hypothesized impacts [47]. Even though our qualitative and quantitative data individually provided some understanding of the influence of PE at each research stage, our mixed methods approach [48, 49] helped us validate and complement our findings from both methods to facilitate a deeper, more comprehensive understanding of patient engagement in research.

PRPs alongside researchers were active members in both project groups. There was equity in the decisions made. PRPs in the two groups performed many parts of the project work, and/or provided insights that were used to shape the direction, methods, analysis, and/or outcomes of the two qualitative research projects. A few crucial activities of influence occurred: during operationalizing the research question to avoid any misinterpretation of the question; during the design stage to ensure that the patient lived experience was embedded in the process and approach and that the method was unbiased and ethical; during the development of the study materials to ensure that the content was clear, ethical and transparent; during the data collection stage to capture high quality data by promoting participant comfort and willingness to share information; and during data interpretation to ensure that the results were relevant and easily understandable. The process of meaningful engagement seen in the groups adds to the synthesis conducted by Greenhalgh et al., in which the authors emphasized the importance of involving patient partners across the research cycle/process and how this involvement gets tailored specifically to the study [15].

Similar results have been seen in other studies using frameworks and tools such as the PPEET, WE-ENACT, and or the PIERS to formally evaluate the impact and capture outcomes of engagement on research. Bhati et al. used the PPEET and the WE-ENACT to assess patient experience and areas of involvement and reported high involvement of PRPs in the initial stages and less involvement in operational activities [50]. Chudyk et al. identified seven activities that PRPs were engaged in across the research cycle, which included identifying and choosing the research topic or method, helping conduct the study, and presenting on behalf of the study team [26]. In the study by Morel et al., PRPs reported an extremely high meaningful engagement similar to the PLG group in our study using the PIERS-22 [51]. A recent work by Babatunde et al., using a mixed method approach, found that PRPs guided the project direction and process, and influenced data collection, analysis, and knowledge translation [52].

The researcher’s roles were operational and advisory; and the clinicians’ role was advisory throughout the project. Despite the differences in the group members’ roles in the two groups, the synergy of collaborative partnership resulted in two projects that were patient-centered, meaningful, understandable, legitimate, rigorous, adaptable, feasible, ethical and transparent, timely, and sustainable, valued by members in the two groups, and by the larger community impacted by this condition.

Formal training of PRP in qualitative methods through programs such as PaCER, and researcher training in POR, as well as resources (human and financial) made available for both groups facilitated meaningful and equitable engagement. The PRP lead specifically had the training and expertise to take on many operational roles such as in data analysis. Similar results are also seen with other educational initiatives such as the Partners in Research (PiR) 2-month online course [53], and the Foundations in Patient-Oriented Research curriculum [54], and in articles emphasizing the importance of thoughtful preparation [54, 55] and training for both researchers and patients for effective collaboration [43, 54–59]. However, regardless of training and experience, the team needs to decide which part of the project would benefit from PE, and not expect PRPs to ‘perform’ the research but participate in ways they desire to be involved [53]. Other known facilitators to PE, also seen in our study, were a flexible plan for engagement [45], recognizing that PRP involvement is an iterative and dynamic process, dependent on the PRP disease state throughout the project [59]. The researcher knowledge of the disease condition was also found to be helpful to promote collaborative relationships.

Equally important, as mentioned in PE literature and seen in our recruitment and retention, a minimum of two PRPs or more should be involved in a project due to project workload issues and PRP health concerns [60]. While previous studies have identified challenges to measuring the influence of patient engagement, including the lack of validated measurement tools, or evaluation methods and frameworks [20, 61, 62], a mixed methods approach, supported by a framework, provided an in-depth understanding of the value of collaborative interactions between researchers, healthcare providers and PRPs in research. The findings, however, may not be applicable in other contexts due to the “un-predictableness” of the stakeholders involved [63] in general, as would be the case with any other study involving small project teams. Partly as a consequence of the small size of the project teams, there was not a great deal of diversity (10/14 participants were white and 12/14 were highly educated) in our two groups. Different stakeholders bring different values, attitudes, and perspectives to projects that could affect PE.

Due to the focused nature of the evaluation and the small size of the two groups, we applied descriptive methodologies. The findings may provide insights to researchers engaging in POR with PRPs by reflecting an understanding of partnerships across all stages of research, and how they can change the way a study is designed, approached and conducted. A key insight, for example, is the role of discussions early in the project that will help guide PRPs and researchers in increasing engagement of research team members. Future exploratory research opportunities include studies with diverse types of PRPs not represented in our study and in different study questions and contexts.

Conclusion

Collaborative and meaningful engagement of patients and researchers can influence all stages of the qualitative research, including design and approach, and outputs. Supported by the SPOR IMAGINE Network and two provincial SPOR SUPPORT Units (AB and BC), this study provides valuable learnings on the influence of PE throughout the entire research process.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the 14 study participants from the two project groups who helped the study team carry out the research. They also acknowledge the support from study team members Aida Fernandes, Executive Director IMAGINE Network; Tracy Wasylak, Chief Program Officer, Strategic Clinical Networks™ with Alberta Health Services; Dr Gilaad Kaplan, Gastroenterologist and Professor in the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary; and Louise Morrin, Senior Provincial Director, Medicine Strategic Clinical Network at Alberta Health Services during the different study phases. The authors are also grateful to the funders of the study: Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research–Inflammation, Microbiome, and Alimentation: Gastro-Intestinal and Neuropsychiatric Effects (SPOR IMAGINE) Network, Canadian Institute of Health Research Network, McMaster University, University of Calgary, University of Alberta, Queen’s University, Dalhousie University, Montreal Heart Institute Research Centre, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Allergan Incorporated, Alberta Innovates, Research Manitoba, and Crohn’s and Colitis Canada.

Declarations

Funding

Funding from the SPOR IMAGINE (Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research, Inflammation, Microbiome, and Alimentation: Gastro-Intestinal and Neuropsychiatric Effects) Network was used to conduct the study. The Network is supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (Funding Reference Number: 1715-000-001) with funding matched by McMaster University, University of Calgary, University of Alberta, Queen’s University, Dalhousie University, Montreal Heart Institute Research Centre, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Allergan Incorporated, Alberta Innovates, Research Manitoba, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada. The IMAGINE Network is sponsoring the open access fee.

Conflict of Interest

Deborah A. Marshall discloses consulting fees from the Office for Health Economics, Novartis, and Analytica during the conduct of this study. She also received support from Illumina for travel expenses to attend a meeting. Nitya Suryaprakash and Karis L. Barker received reimbursement of expenses related to conference attendance from the SPOR IMAGINE Chronic Disease Network. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Data Availability

The ethics approval for this study does not support the sharing of raw data.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the respective research ethics boards of the University of Calgary [REB20-1563] and the University of British Columbia [H20-03385]. The authors certify that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards detailed in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Deborah A. Marshall conceptualized the study and led the design, conduct, and analysis of this study and the drafting of and revising of the article. Danielle C. Lavelle and Stirling Bryan conceptualized the study and led the design, conduct, and analysis of this study and helped revise the manuscript. Nitya Suryaprakash and Karis L. Barker participated in the design, coordination, data collection, conduct, and analysis of the study and in drafting and revising the manuscript. Paul Moayyedi contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of data and reviewed the manuscript critically. All other authors participated in the design, conduct, and analysis of the study and reviewed the manuscript critically. All authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Sandra Zelinsky: Patient Author.

References

- 1.Harrington RL, Hanna ML, Oehrlein EM, et al. Defining patient engagement in research: results of a systematic review and analysis: report of the ISPOR Patient-Centered Special Interest Group. Value Health. 2020;23(6):677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merker VL, Hyde JK, Herbst A, et al. Evaluating the impacts of patient engagement on health services research teams: lessons from the veteran consulting network. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(1):33–41. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06987-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boaz A, Robert G, Locock L, et al. What patients do and their impact on implementation. J Health Organ Manag. 2016;30(2):258–278. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-02-2015-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffett L. Patient engagement: what partnering with patient in research is all about. Thromb Res. 2017;150:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Patient Engagement in Research Resources; 2020. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51916.html. Accessed July 7, 2022.

- 6.Hyde C, Dunn KM, Higginbottom A, Chew-Graham CA. Process and impact of patient involvement in a systematic review of shared decision making in primary care consultations. Health Expect. 2017;20(2):298–308. doi: 10.1111/hex.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarron TL, Clement F, Rasiah J, et al. Patients as partners in health research: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2021;24(4):1378–1390. doi: 10.1111/hex.13272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes P, Nocon A, Booth M, et al. A service users’ research advisory group from the perspectives of both service users and researchers. Health Soc Care Community. 2002;10(5):402–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tapp H, Derkowski D, Calvert M, Welch M, Spencer S. Patient perspectives on engagement in shared decision-making for asthma care. Family Pract. 2017;34(3):353–357. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson T, Miller J, Teare S, et al. Patient perspectives on engagement in decision-making in early management of non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome: a qualitative study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0555-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zabalan C, Pennings P, Clausen J, et al. EULAR Guide: Starting a Patient Research Partner (PRP) Group on a National Level. September 2021:13. https://www.eular.org/myUploadData/files/2021_prp_guide_long.pdf.

- 12.Canadian Institute for Health Research. Strategy for patient-oriented research–patient engagement framework; 2020. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 13.Lavallee DC, Williams CJ, Tambor ES, Deverka PA. Stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness research: how will we measure success? J Comp Effect Res. 2012;1(5):397–407. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliver SR, Rees RW, Clarke-Jones L, et al. A multidimensional conceptual framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. Health Expect. 2008;11(1):72–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenhalgh T, Hinton L, Finlay T, et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):785–801. doi: 10.1111/hex.12888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manafo E, Petermann L, Mason-Lai P, Vandall-Walker V. Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0282-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanderhout S, Nicholls S, Monfaredi Z, et al. Facilitating and supporting the engagement of patients, families and caregivers in research: the “Ottawa model” for patient engagement in research. Res Involv Engag. 2022;8(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s40900-022-00350-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Association for Public Participation. Core Values, Ethics, Spectrum – The 3 Pillars of Public Participation. https://www.iap2.org/page/pillars. Accessed Apr 25, 2022.

- 19.Johannesen J. Patient views on “ladders of engagement”; 2018. 10.13140/RG.2.2.29370.85444.

- 20.Boivin A, L’Espérance A, Gauvin FP, et al. Patient and public engagement in research and health system decision making: a systematic review of evaluation tools. Health Expect. 2018;21(6):1075–1084. doi: 10.1111/hex.12804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauzon-Schnittka J, Audette-Chapdelaine S, Boutin D, et al. The experience of patient partners in research: a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Res Involv Engag. 2022;8(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s40900-022-00388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient. 2014;7(4):387–395. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dillon EC, Tuzzio L, Madrid S, et al. Measuring the impact of patient-engaged research: how a methods workshop identified critical outcomes of research engagement. J Patient-Centered Res Rev. 2017;4(4):237–246. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell J, Fudge N, Greenhalgh T. The impact of public involvement in health research: what are we measuring? Why are we measuring it? Should we stop measuring it? Res Involv Engag. 2020;6(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00239-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, Herron-Marx S. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(1):28–38. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chudyk AM, Stoddard R, McCleary N, et al. Activities and impacts of patient engagement in CIHR SPOR funded research: a cross-sectional survey of academic researcher and patient partner experiences. Res Involv Engag. 2022;8(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s40900-022-00376-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creswell J, Clark VP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton CB, Hoens AM, McKinnon AM, et al. Shortening and validation of the Patient Engagement In Research Scale (PEIRS) for measuring meaningful patient and family caregiver engagement. Health Expect. 2021;24(3):863–879. doi: 10.1111/hex.13227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moayyedi P, MacQueen G, Bernstein CN, et al. IMAGINE Network’s Mind And Gut Interactions Cohort (MAGIC) Study: a protocol for a prospective observational multicentre cohort study in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e041733. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 4. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Admin Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2015;42(5):533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.IMAGINE. Compensation and Guidelines. https://imaginespor.com/compensation-policy/. Accessed Apr 25, 2022.

- 33.PCORI. Engagement Activity Inventory (NET-ENACT AND WE-ENACT). https://ceppp.ca/en/evaluation-toolkit/pcori-engagement-activity-inventory-net-enact-and-we-enact/. Accessed Aug 10, 2022.

- 34.PCORI. Ways of Engaging—ENgagement ACtivity Tool (WE-ENACT)—Patients and Stakeholders 3.0 Item Pool. http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-WE-ENACT-3-0-Patients-Stakeholders-Item-Pool-080916.pdf. Accessed Apr 25, 2022.

- 35.PaCER. Patient and Community Engagement Research. https://pacerinnovates.ca. Accessed Apr 25, 2022.

- 36.van Overbeeke E, Vanbinst I, Jimenez-Moreno AC, Huys I. Patient centricity in patient preference studies: the patient perspective. Front Med. 2020;7:93. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abelson J, Tripp L, Kandasamy S, et al. Supporting the evaluation of public and patient engagement in health system organizations: results from an implementation research study. Health Expect. 2019;22(5):1132–1143. doi: 10.1111/hex.12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berg BL, Lune H. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 9. Boston: Pearson; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawulich B. Doing social research: a global context. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education; 2012. Collecting data through observation; pp. 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall DA, Suryaprakash N, Lavallee DC, et al. Exploring the outcomes of research engagement using the observation method in an online setting. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e073953. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marshall DA, Suryaprakash N, Bryan S, et al. Measuring the impact of patient engagement in health research: an exploratory study using multiple survey tools. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2023 doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwad045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Best Qualitative Data Analysis Software for Researchers | NVivo. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home. Accessed Apr 25, 2022.

- 43.Shklarov S, Marshall DA, Wasylak T, Marlett NJ. “Part of the Team”: mapping the outcomes of training patients for new roles in health research and planning. Health Expect. 2017;20(6):1428–1436. doi: 10.1111/hex.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marlett N, Shklarov S, Marshall D, et al. Building new roles and relationships in research: a model of patient engagement research. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1057–1067. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0845-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Etchegary H, Pike A, Patey AM, et al. Operationalizing a patient engagement plan for health research: sharing a codesigned planning template from a national clinical trial. Health Expect. 2022;25(2):697–711. doi: 10.1111/hex.13417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skovlund PC, Nielsen BK, Thaysen HV, et al. The impact of patient involvement in research: a case study of the planning, conduct and dissemination of a clinical, controlled trial. Res Involv Engag. 2020;6(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00214-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ball S, Harshfield A, Carpenter A, et al. Patient and public involvement in research: enabling meaningful contributions. RAND Corp. 2019 doi: 10.7249/RR2678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wasti SP, Simkhada P, van Teijlingen ER, et al. The growing importance of mixed-methods research in health. Nepal J Epidemiol. 2022;12(1):1175–1178. doi: 10.3126/nje.v12i1.43633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhati DK, Fitzgerald M, Kendall C, Dahrouge S. Patients' engagement in primary care research: a case study in a Canadian context. Res Involv Engag. 2020;6(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00238-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morel T, Schroeder K, Cleanthous S, et al. The value of co-creating a clinical outcome assessment strategy for clinical trial research: process and lessons learnt. Res Involv Engag. 2023;9:98. doi: 10.1186/s40900-023-00505-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Babatunde S, Ahmed S, Santana MJ, et al. Working together in health research: a mixed-methods patient engagement evaluation. Res Involv Engag. 2023;9:62. doi: 10.1186/s40900-023-00475-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Courvoisier M, Baddeliyanage R, Wilhelm L, et al. Evaluation of the partners in research course: a patient and researcher co-created course to build capacity in patient-oriented research. Res Involv Engag. 2021;7(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s40900-021-00316-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bell T, Vat LE, McGavin C, et al. Co-building a patient-oriented research curriculum in Canada. Res Involv Engag. 2019;5(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s40900-019-0141-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bird M, Ouellette C, Whitmore C, et al. Preparing for patient partnership: a scoping review of patient partner engagement and evaluation in research. Health Expect. 2020;23(3):523–539. doi: 10.1111/hex.13040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vat LE, Ryan D, Etchegary H. Recruiting patients as partners in health research: a qualitative descriptive study. Res Involv Engag. 2017;3(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s40900-017-0067-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harrison JD, Auerbach AD, Anderson W, et al. Patient stakeholder engagement in research: a narrative review to describe foundational principles and best practice activities. Health Expect. 2019;22(3):307. doi: 10.1111/hex.12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Langlois S, Mehra K. Teaching about partnerships between patients and the team: exploring student perceptions. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(6):1589–1594. doi: 10.1177/2374373520933130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boaz A, Hanney S, Borst R, et al. How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0337-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kirwan JR, de Wit M, Frank L, Haywood KL, Salek S, Brace-McDonnell S, Lyddiatt A, Barbic SP, Alonso J, Guillemin F, Bartlett SJ. Emerging guidelines for patient engagement in research. Value Health. 2017;20(3):481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vat LE, Finlay T, Jan Schuitmaker-Warnaar T, et al. Evaluating the “return on patient engagement initiatives” in medicines research and development: a literature review. Health Expect. 2020;23(1):5–18. doi: 10.1111/hex.12951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.L’Espérance A, O’Brien N, Grégoire A, et al. Developing a Canadian evaluation framework for patient and public engagement in research: study protocol. Res Involv Engag. 2021;7(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40900-021-00255-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Staley K. ‘Is it worth doing?’ Measuring the impact of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engag. 2015;1(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s40900-015-0008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The ethics approval for this study does not support the sharing of raw data.