Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to compare the anesthetic efficacy of 4% articaine, 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.5% ropivacaine (with 1:200,000 adrenaline) during surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars.

Materials and methods

The study included 75 patients randomly divided into three equal groups of 25 patients each. The study variables were: onset of anesthetic action, duration of surgery and anesthesia and postoperative analgesia. A visual analog scale was used to assess pain at different time intervals. Statistical analysis revealed insignificant difference among groups in terms of volume of anesthetic solution used, quality of anesthesia, surgical difficulty and duration of surgery.

Results

The mean onset time was significantly (P < 0.001) shorter for articaine (1.14 min) than ropivacaine (2.18 min) and bupivacaine (2.33 min). However, the duration of anesthesia as well as analgesia was significantly (P < 0.001) longer for bupivacaine (483.6 min and 464 min) and ropivacaine (426.6 min and 459 min) as compared to articaine (232.8 min and 191.4 min), respectively. Also, on comparing three groups pain scores at 6th postoperative hour were significant (P < 0.01).

Conclusion

Ropivacaine and bupivacaine can be safely used in patients where longer duration of surgery is anticipated.

Keywords: Ropivacaine, Bupivacaine, Articaine, Pain, Anesthesia

Introduction

Amide types of local anesthetics with moderate to long duration of action are commonly used for maxillofacial surgeries. Thus, pain control after the surgical removal of impacted third molar can be increased by using local anesthetic with a more prolonged action. Articaine, bupivacaine and ropivacaine are all amide-type local anesthetics.

Articaine (4%) has a chemical structure different from other local anesthetics due to the substitution of the aromatic ring with thiophene ring, and presence of an additional ester group which provides articaine with increased lipid solubility, intrinsic potency and greater plasma protein binding (approximately 95%). Biotransformation of articaine occurs in both the plasma and liver. The rapid conversion of ester moiety to carboxylic acid moiety is clinically reflected by short latency, shorter half life, increased duration of anesthesia, superior systemic safety and bony diffusion [1].

Bupivacaine (0.5%) being a racemic local anesthetic, has an intermediate onset of action and long duration of anesthesia, allowing a slow return to normal sensation [2]. It provides additional analgesia time known as residual analgesia [3] and thus minimizes the duration of postoperative pain.

Ropivacaine is structurally a pure enantiomer containing > 99% “S” form and differs from bupivacaine in the length of their side chains of carbon on the third azoth atom [4]. It is less lipophilic than bupivacaine and less likely to penetrate large myelinated motor fibers and therefore has a selective action on pain transmitting nerve fibers rather than those involved in motor functions. It is metabolized extensively in the liver and excreted by kidney. It is available in various concentrations such as 0.25%, 0.375%, 0.5%, 0.75% and 1%. It has an intermediate onset but longer duration of action with high plasma protein binding (94%) [5].

However, there are no studies in the literature on comparison of three different local anesthetic solutions for surgical removal of lower third molars. Hence, the aim of the present study was to compare the safety and efficacy of 4% articaine, 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.5% ropivacaine (each with 1:200,000 adrenaline) during surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars.

Material and Methods

The present study was undertaken in 75 patients, who reported to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Sri Guru Ram Das Institute of Dental Sciences and Research for surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars. The patients were divided into 3 groups of 25 patients each. Inclusion criteria included ASA I patients, medical history revealing no systemic illness and patients having no signs of inflammation or infection at the proposed extraction site. Patients with known allergic reaction to local anesthetic agents or any of its constituents (methyl paraben, etc.), allergy to aspirin, ibuprofen or any similar drug, patients with pregnancy or on current lactation and patients with known history of drug abuse or alcoholism were excluded from the study. Diagnosis was made on the basis of history, clinical examination and radiological examination. The intraoral periapical radiographs were taken to ensure the similarity of tooth inclination and angulation, hence maintaining similar index of surgical difficulty and duration of surgical intervention in each group. Informed consent was obtained from each patient after getting approval from Institutional Ethical Committee. All the patients were prescribed antianxiety drug (Alprazolam 0.25 mg) 45 min before the surgery. For three equal sized groups, a priori power analysis revealed that 14 patients would be required per group with α = 0.05 and β = 0.1. To compensate for the possible dropouts, we therefore aimed to enroll 75 patients in total (25 each group).

Each patient was operated by the same senior Oral and Maxillofacial surgeon, using same standardized surgical protocol. The study was conducted using a block randomization method. After sensitivity test for all the respective anesthetic agents, first 25 patients received 4% articaine with 1:200,000 adrenaline (Septocaine, Septodont Ltd, UK), next 25 patients received 0.5% bupivacaine with 1:200,000 adrenaline (Anavin, Neon laboratories Ltd, India), and last 25 patients received 0.5% ropivacaine with 1:200,000 adrenaline (Ropin, Neon laboratories Ltd, India). Each patient received a total of 4 ml of anesthetic solution after double aspiration technique to prevent any intravascular injection. Three milliliters of the solution was used for achieving regional anesthetic blockade of inferior alveolar and lingual nerves and 1 milliliter for infiltration of long buccal nerve opposite to lower second and third molars. Postoperatively, patients were prescribed Tab Augmentin 625 mg (Amoxycillin 500 mg + Clavulanate 125 mg) (GSK pharmaceuticals) TDS to prevent infection and Tab Brufen 600 (Ibuprofen 600 mg) (Abbott pharmaceuticals) TDS as analgesic—anti-inflammatory, both for 5 days. The first Brufen tablet was given only when the patient started complaining of pain.

The following parameters were assessed

Total volume of anesthetic solution used during surgery (in ml)

Onset of action of anesthetic agent was determined subjectively by loss of sensibility of the lower lip, corresponding half of the tongue and the buccal mucosa. Objectively, the presence or absence of sensibility to pin prick sensation was determined by using 26-gauge needle applied about 7 mm from gingival margin on the attached gingiva at the surgical site where mandibular third molar was impacted [4].

Quality of anesthesia, provided by the local anesthetic during surgery, was evaluated by the surgeon, according to modification of the method described by Sisk. This was based on a 3-point category rating scale: 1—no discomfort reported by the patient during surgery; 2—any discomfort reported by the patient during surgery, without the need of additional anesthesia; 3—any discomfort reported by the patient during surgery, with the need of additional anesthesia

Difficulty of surgery was rated by the surgeon at the completion of each extraction, according to a 3-point category rating scale:1—easy, 2—normal, 3—complicated.

Duration of surgery after anesthetic administration (in minutes) corresponded to the period between surgical incision and placement of the last suture.

Duration of anesthesia was recorded from the time of onset of complete anesthesia to the time when the anesthetic effect began to fade. The time at which all soft tissue sensation returned to normal, was also recorded.

Duration of postoperative analgesia was determined by the time interval between the end of surgery and ingestion of first Brufen tablet for pain relief.

Systolic, diastolic pressure and heart rate: These parameters were noted before surgery, during surgery and after suturing. During surgery, two measurements were taken: one immediately after the administration of the local anesthetic and another 5 mins later.

Incidence, type and severity of adverse reactions were noted during surgery and in the postoperative follow-up period. These were observed either by the surgeon or reported by the patient.

Subjective pain evaluation was noted with the aid of a 100-mm-length visual analogue scale (VAS), with the markings between

1 and 25 as mild pain

26 and 50 as moderate pain

51 and 75 as intense pain

76 and 100 as unbearable pain

Patients recorded the intensity of pain after completion of surgery, the moment when the effect of anesthesia completely wore off and also at 6, 12 and 24 h postoperatively.

The data obtained were subjected to statistical analysis to compare the efficacy of three local anesthetic solutions used during surgical removal of mandibular third molars. For normally distributed data (age, volume of local anesthesia used, time to onset, duration of surgery, duration of anesthesia, duration of postoperative analgesia), Means ± SD was compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc test for multiple comparison (Bonferroni). For skewed data or for scores, (VAS and difficulty of surgery) three groups were compared using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Mann–Whitney test for multiple comparison. Categorical data (gender, quality of anesthesia) were presented as number, percentages and compared by Chi-square or Fischer’s test. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS for windows version 17 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA).

Observations

The study comprised of 75 patients (40 males and 35 females) with mean age as 29.52 (18–50) years.

The difference in the mean volume of three anesthetic solutions 4% articaine, 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.5% ropivacaine (each with 1:200,000 adrenaline) used during the surgery was found to be statistically nonsignificant (P = 0.931). However, 4 patients (16%) in bupivacaine group, 3 patients (12%) in ropivacaine group and 1 patient (4%) in articaine group required additional nerve block anesthesia (Table 1). The additional anesthesia was given in the patients who complained of pain during elevation due to pocket distal to second molar as a result of exacerbated proprioception.

Table 1.

Volume of anesthetic used, quality of anesthesia, difficulty and duration of surgery in patients who underwent surgical removal of third molars using three different anesthetic agents

| Parameters | Articaine | Bupivacaine | Ropivacaine | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume of anesthetic used (ml) | 4.07 ± 0.36 | 4.10 ± 0.25 | 4.10 ± 0.28 | .931NS |

|

Quality of anesthesia No discomfort reported during surgery Discomfort reported without need of additional anesthesia Discomfort reported with need of additional anesthesia |

22 2 1 |

20 1 4 |

19 4 2 |

.195NS |

| Difficulty of surgery | 1.48 ± 0.65 | 1.52 ± 0.58 | 1.52 ± 0.71 | .922NS |

| Duration of surgery (Mins) | 20.00 ± 7.96 | 24.04 ± 7.96 | 23.00 ± 6.59 | .151NS |

NS—nonsignificant values in mean ± SD

P > 0.05 (nonsignificant)

Quality of anesthesia was most successful in articaine group (88%), followed by bupivacaine group (80%) and then ropivacaine group (76%). However, our findings for quality of anesthesia, surgical difficulty and duration of surgery were found to be statistically nonsignificant among the three groups (Table 1).

The mean onset of action was shortest in articaine group followed by ropivacaine group and was the longest for bupivacaine group as depicted in Table 2. The difference between all the groups was statistically highly significant regarding subjective and objective onset of action (p < 0.001). Among the three groups there was highly significant difference between ropivacaine and articaine group (p < 0.001), between bupivacaine and articaine group (p < 0.001) with respect to subjective and objective onset of action. However, no significant difference was observed between ropivacaine and bupivacaine group (p = 1).

Table 2.

Onset of action, duration of anesthesia and postoperative analgesia

| Parameters | Articaine | Bupivacaine | Ropivacaine | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Onset of action (min) Numbness of lip and tongue Pinprick |

1.14 ± 0.84 1.49 ± 0.45 |

2.33 ± 0.53 4.44 ± 1.48 |

2.18 ± 0.84 4.18 ± 1.00 |

< .001** < .001** |

|

Duration of anesthesia (min) Initial recovery of soft tissue anesthesia Final recovery from anesthesia |

70.8 ± 22.8 232.8 ± 34.2 |

365.4 ± 41.4 483.6 ± 129 |

210.6 ± 114 426.6 ± 85.2 |

< .001** < .001** |

| Duration of postoperative analgesia (min) | 191.4 ± 33.6 | 464 ± 74.4 | 459 ± 64.8 | 0.000 |

P = 0.000: Significant

**P < 0.001: Highly significant values in mean ± SD

The mean time for initial recovery of soft tissue anesthesia and complete anesthesia was shortest in articaine group followed by ropivacaine group and was the longest for bupivacaine group. Statistically highly significant difference was observed among all the groups regarding initial recovery of soft tissue and final recovery from anesthesia (p < 0.001). Regarding final recovery of soft tissue anesthesia, there was no significant difference between ropivacaine and bupivacaine (p = 0.367). However, highly significant difference was observed on comparing bupivacaine with articaine and ropivacaine with articaine (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

The duration of postoperative analgesia showed statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) among the three groups. Maximum number of patients who did not require postoperative analgesic were observed in ropivacaine group (n- 7, 28%) followed by 4 (16%) patients in bupivacaine and then 2(8%) patients in articaine group. No significant difference was observed in duration of postoperative analgesia between ropivacaine and bupivacaine (p = 1). However, a significant difference was observed between bupivacaine and articaine and also between ropivacaine and articaine (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Hemodynamic parameters showed slight alteration in both systolic, diastolic blood pressure and heart rate immediately after local anesthesia in all the three groups (Table 3). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the hemodynamic indices before, during the surgery and after suturing among the three groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of mean value of hemodynamic indices

| Timings | Articaine (mean ± SD) | Bupivacaine (mean ± SD) |

Ropivacaine (mean ± SD) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sys.BP, mmHg |

Before LA Imm. after LA After 5 min After suturing |

128.84 ± 12.31 133.84 ± 13.02 130.92 ± 14.92 127.08 ± 11.56 |

127.48 ± 10.32 132.20 ± 10.52 129.04 ± 15.24 125.56 ± 11.39 |

126.60 ± 9.06 130.88 ± 14.36 127.44 ± 12.30 124.80 ± 9.64 |

0.756NS 0.580NS 0.979NS 0.219NS |

| Dia. BP, mmHg |

Before LA Imm. after LA After 5 min After suturing |

83.40 ± 9.56 85.28 ± 11.93 84.32 ± 11.32 81.84 ± 9.65 |

83.36 ± 7.61 85.08 ± 8.37 84.20 ± 8.71 82.92 ± 7.34 |

81.40 ± 7.21 83.52 ± 9.35 80.68 ± 8.22 77.92 ± 7.50 |

0.617NS 0.793NS 0.212NS 0.085NS |

| HR, beats/min |

Before LA Imm. after LA After 5 min After suturing |

82.60 ± 12.87 84.68 ± 14.96 88.80 ± 14.15 78.86 ± 12.82 |

83.04 ± 12.44 86.84 ± 14.36 87.04 ± 12.86 83.80 ± 11.69 |

86.52 ± 16.46 88.08 ± 14.92 88.52 ± 18.32 78.96 ± 13.34 |

0.373NS 0.713NS 0.617NS 0.276NS |

Sys. BP systolic BP; Dia. BP diastolic BP; HR heart rate; LA local anesthetic; Imm. immediately; Mins minutes; NS nonsignificant; SD standard deviation

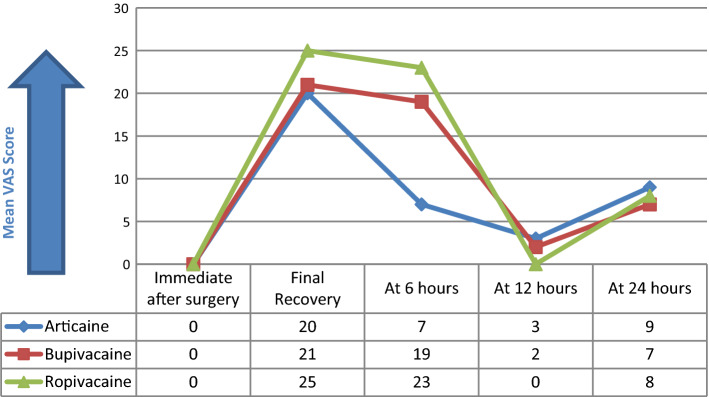

Immediately after surgery none of the patients experienced any pain. At the time when anesthesia wore off completely, the difference in the mean pain score among three groups was found to be statistically insignificant (P = 0.800). The return of pain sensation was fastest in articaine group; hence, 24 patients (96%) consumed oral analgesic between 3rd and 4th postoperative hour and did not experience much pain at 6th postoperative hour. Thus, mean pain score at 6th postoperative hour was reported more in ropivacaine group as compared to bupivacaine group with the significant difference between them (P = 0.01). At 12th and 24th postoperative hour there was no significant difference in the mean pain score among all the groups (P = 0.74, 0.92, respectively) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

VAS score for pain at different time intervals

No adverse reactions due to use of three local anesthetic solutions were observed by the surgeon or reported by the patient perioperatively/postoperatively.

Discussion

Pain control is an essential part of routine oral surgical procedures performed with local anesthetics which interrupt the propagation of nerve impulse in reversible manner [6].

Speed of onset of an individual local anesthetic is chiefly related to the lipid solubility of nonionized portion of the drug and therefore its ability to diffuse across the membrane. The degree of ionization is governed by its pKa, and therefore, pKa has the main influence on the onset time [7]. In the present study, the mean time of onset as referred to lip and tongue numbness and on pinprick test was least in articaine group followed by ropivacaine group and then bupivacaine group. Our results are supported by Santos et al. [8] (1.58 ± 0.08 min) for articaine, Ergen and Kopp [9] (2–3 mins) for ropivacaine and Gregoria et al. [10] (2.51 ± 0.21minutes) for bupivacaine. Contrarily, Puchades et al. [11] reported longer mean time of onset with 4% articaine as compared to 0.5% bupivacaine both with 1:200,000 epinephrine and suggested that latency period was influenced by other factors besides pKa such as anesthetic technique.

A weaker binding of ropivacaine to extraneural fat and tissues than bupivacaine also contributed to greater availability of ropivacaine for transfer to the site of action in the nerves during peripheral nerve blockade. In the present study also the mean time of onset in ropivacaine group was faster as compared to bupivacaine group. Our results are in agreement with Brkovic et al. [12] who also reported that onset of action took longer time in 0.5% bupivacaine group as compared to 0.75% ropivacaine without addition of vasoconstrictor. The results by Crincoli et al. [13] regarding onset of action were in agreement with the present study.

In this study the mean duration of soft tissue anesthesia was longest for 0.5% bupivacaine followed by 0.5% ropivacaine and then 4% articaine. Almost similar range for duration of anesthesia (492 ± 272.4 min) has been reported by Eriksson and Moya [3] on using 0.5% bupivacaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine. Brkovic et al. [12] also reported the duration of anesthesia to be slightly longer with 0.5% bupivacaine (688 ± 85 min) as compared to 0.75% ropivacaine group (582 ± 67 min) with reference to lower lip numbness. In the present study 0.5% ropivacaine was used with 1:200,000 adrenaline which is responsible for its longer duration of anesthesia (426.6 ± 85.2 min) in contrast to the study by Ernberg and Kopp [9] who used 0.5% ropivacaine without epinephrine for inferior alveolar nerve block and found the duration of anesthesia as 320 min. Similarly, Kennedy et al. [14] also observed short duration of anesthesia with 0.5% ropivacaine without adrenaline (362 ± 101.31 min) as compared to 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.5% ropivacaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine (512.25 ± 179.76 min and 410 ± 85.85 min, respectively). The shorter duration of anesthesia with ropivacaine as compared to bupivacaine could be due to lesser lipid solubility of ropivacaine and consequent lesser absorption by nerve tissue.

The results for duration of anesthesia as reported by Tofoli et al. [15]; Santos et al. [8] (260 ± 45 min, 240.83 ± 16.20 min, respectively) on using 4% articaine are in conformity to the present study. Our results are also in accordance with the study by Gregorio et al. [10] who reported longer anesthesia in 0.5% bupivacaine (310.92 ± 49.86 min) than 4% articaine (245 ± 16.60 min).

In this study duration of analgesia was more in bupivacaine group followed by ropivacaine and then articaine group. Our results are supported by the studies of Nespeca [16]; Chapman and Macleod [17]. Lower concentrations of ropivacaine (0.25% and 0.375%) have a selective analgesic effect because clinically they block thin Aδ and C nerve fibers more readily than large Aβ fibers. Although at lower concentrations it may be suitable for providing postoperative analgesia, higher concentrations (0.5% and 0.75%) are required for effective surgical anesthesia. The higher concentration (0.5% and 0.75%) used for inferior alveolar nerve block by Sharrawy and Yagiela [18] in their study provided both surgical anesthesia and postoperative analgesia, with pain relief significantly outlasting soft tissue numbness. This is consistent with the findings of the current study in which postoperative pain relief also outlasted soft tissue anesthesia. Almost similar range for duration of postoperative analgesia (5.6 ± 0.4 h and 6 h, respectively) has been reported by Sharrawy and Yagiela [18]; Deleuze et al. [19] on using 0.5% and 0.75% ropivacaine, respectively, for surgical removal of lower third molar.

The long duration of postoperative analgesia of articaine (191.4 ± 33.6 min) is because of its ability to readily diffuse through tissues and due to the presence of thiophene group in the molecule which increases its liposolubility [20]. Gregorio et al. [10]; Santos et al. [8], respectively, also reported the duration of postoperative analgesia almost in similar range on using 4% articaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine.

Eriksson and Moya [3] reported the longer duration of postoperative analgesia in 0.5% bupivacaine group compared to 4% articaine group which is in accordance with the present study. Mansour et al. [21] reported that the time for intake of first analgesic was slightly delayed in 0.5% bupivacaine group than in 0.75% ropivacaine group. Their study showed that ropivacaine (9.6 h) did not differ from bupivacaine (10.3 h) with respect to duration of analgesia which is in agreement with the present study.

The use of long-acting local anesthetic agent reduces the need for additional anesthetic agents during intervention, and also analgesia leads to reduced need for administration of postoperative analgesics drugs [12, 22]. According to Balakrishnan et al. [23] on using bupivacaine, there is a period of analgesia that persists after the return of sensation, during which time the need for strong analgesics is reduced. In the present study, 7 (28%) patients in ropivacaine group, 4(16%) patients in bupivacaine group and 2(8%) patients in articaine group did not require any analgesic tablets postoperatively upto 24 h. In articaine group most of the patients had Tab Brufen 600 mg at 3rd or 4th postoperative hour which has dose-dependent duration of action of around four to 8 h; therefore, the mean pain score evaluated at 6th postoperative hour was more in ropivacaine group followed by bupivacaine and then articaine group. The patients in ropivacaine and bupivacaine group had analgesic at 7th or 8th postoperative hour. Our study is in agreement with Bouloux and Punnia-Moorthy [24]; Brkovic et al. [12], Mansour et al. [21] who reported the increase duration of analgesia with long-acting anesthetics. According to Mansour et al. [21] there was no requirement of analgesic tablet by 20% patients in bupivacaine group and 16% patients in ropivacaine group.

In our study, patients experienced mild pain at 12th and 24th h postoperatively in all the three groups which is in agreement with the findings of Chapman [25], Mansour et al. [21].

Various studies have also shown toxic effects on central nervous and cardiovascular system with use of longer-acting anesthetics like ropivacaine [26]. The prolonged duration of lip numbness seen with bupivacaine can cause difficulty in eating, drinking and speaking and inadvertent biting of lips. A split mouth study design and larger sample size can be chosen in future to reset any bias.

Hence, to conclude the use of longer-acting anesthetics like bupivacaine and ropivacaine, as compared to shorter-acting ones like articaine, improve the quality of care after third molar surgery, due to the fact that most of postoperative time is covered by residual effects of anesthesia, thus ultimately reducing the necessity of analgesic consumption. They can be easily and safely used in patients where longer duration of surgery is anticipated and also have a great safety profile.

Funding

I would like to state that there is no external source of funding.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

There is source of conflict, and the research involves human participants with no harm.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Baba Farid University of health sciences, Faridkot, Punjab.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from each and every patient.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rebolledo AS, Molina ED, Aytes LB, Escoda CG. Comparative study of the anesthetic efficacy of 4% articaine versus 2% lignocaine in inferior alveolar nerve block during surgical extraction of impacted lower third molars. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Buccal. 2007;12:E139–E144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sisk AL. Long-acting local anesthetics in dentistry. Anesth Prog. 1992;39:53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erikkson AT, Moya BG. Comparative study of two local anesthetics in the surgical extraction of mandibular third molars: bupivacaine and articaine. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Buccal. 2011;16(3):E390–E396. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16.e390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buric N. The assessment of anesthetic efficacy of ropivacaine in oral surgery. N Y State Dent J. 2006;72(3):36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee A, Fagan D, Lamont M, Tucker GT, Halldin M, Scott DB. Disposition kinetics of ropivacaine in humans. Anesth Analg. 1989;69:736–738. doi: 10.1213/00000539-198912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pipa-Vallejo A, Garcia-Pola-Vallejo MJ. Local anesthetics in dentistry. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2004;9:440–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giovannitti JA, Rosenberg MB, Phero JC. Pharmacology of local anesthetic used in oral surgery. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N AM. 2013;25(3):453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos CF, Modena KCS, Giglio FPM, Sakai VT, Calvo AM, Columbini BL. Epinephrine concentration (1:100000 or 1:200000) Does not affect the clinical efficacy of 4% articaine foe lower third molar removal: a double-blind, randomized, crossover study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2445–2452. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernberg M, Kopp S. Ropivacaine for dental anesthesia: a dose-finding study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:1004–1010. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.34409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregoria LVL, Giglio FPM, Sakai VT, Modena KCS, Columbini BL, Calvo AM. A comparison of the clinical anesthetic efficacy of 4% articaine and 0.5% bupivacaine (both with 1:200000 epinephrine) for lower third molar removal. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Orl Endod. 2008;106:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puchades MS, Vilchez-Perez MA, Catellon EV, Garcia JP, Aytes LB, Escoda CG. Bupivacaine 0.5% versus 4% articaine for the removal of lower third molars. A crossover randomized controlled trial. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:462–468. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brkovic B, Stojic D, Colic S, Milenkovic A, Todorovic L. Analgesic efficacy of 07.5% ropivacaine for lower third molar surgery. Balk J Stom. 2008;12:31–33. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crincoli V, Favia G, LImongelli L, Tempesta A, Brienza N. The effectiveness of ropivacaine and mepivacaine in the postoperative pain after third molar surgery. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12:862–866. doi: 10.7150/ijms.13072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy M, Reader A, Beck M, Weaver J. Anesthetic efficacy of ropivacaine in maxillary anterior infiltration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Oral Endod. 2001;91:406–412. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.114000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tofoli GR, Ramacciato JC, Oliveria PC, Volpato MC, Groppo FC, Ranali J. Comparison of effectiveness of 4% articaine associated with 1:100000 or 1:200000 epinephrine in inferior alveolar nerve block. Anesth Prog. 2003;50:164–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nespeca JA. Clinical trials with bupivacaine in oral surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;42(3):301–307. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman PJ, Macleod AWG. A clinical study of bupivacaine for mandibular anesthesia in oral surgery. Anesth Prog. 1985;32:69–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharrawy EE, Yagiela JA. Anesthetic efficacy of different ropivacaine concentrations for inferior alveolar nerve block. Anesth Prog. 2006;53:3–7. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2006)53[3:AEODRC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deleuze A, Marret E, Vial G, Schmitt S, Cordier M, Gentili ME. Infiltration with ropivacaine decreases postoperative pain following extraction of third molar teeth in ambulatory surgery. Ambul Surg. 2007;13(2):50–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vree TB, Gielen MJ. Clinical pharmacology and the use of articaine for local and regional anesthesia. Best Pract Res Clin Anesthesiol. 2005;19(2):293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansour NA, AL-Belasy FS, Tawfik MA, Marzook HA. Ropivacaine versus bupivacaine in postoperative pain control. J Biotechnol Biomater. 2012;2(4):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stojanovic S, et al. Clinical significacy of long acting local anesthetics in oral surgery. Acta Stomatol Naissi. 2010;26:967–976. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balakrishnan K, Ebenezer V, Dakir A, Kumar S, Prakash D. Bupivacaine versus lignocaine as the choice of local anesthetic agent for impacted third molar surgery a review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7:S230–S233. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.155921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouloux GF, Punnia- MA. Bupivacaine versus lidocaine for third molar surgery: a double blind, randomized, crossover study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:510–514. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman PJ. Review: bupivacaine- A long acting local anesthetic. Aust Dent J. 1987;32:288–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1987.tb04156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knudsen K, Surkula MB, Blomberg S, Sjovali J, Edvardson N. Central nervous and cardiovascular effects of iv infusions of ropivacaine, bupivacaine and placebo in volunteers. Br J Anesth. 1997;78:507–514. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]