Key Points

Question

Does combined transarterial chemoembolization and sorafenib (SOR-TACE) improve survival in patients with recurrent intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma after R0 hepatectomy with positive microvascular invasion compared with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) alone?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 162 patients, those treated with SOR-TACE had a significantly longer median overall survival than TACE alone (22.2 months vs 15.1 months) and median progression-free survival (16.2 months vs 11.8 months). The SOR-TACE safety profile was acceptable compared with TACE alone.

Meaning

SOR-TACE for patients with recurrent intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion improved survival compared with TACE alone.

Abstract

Importance

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is commonly used to treat patients with recurrent intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and positive microvascular invasion (MVI); however, TACE alone has demonstrated unsatisfactory survival benefits. A previous retrospective study suggested that TACE plus sorafenib (SOR-TACE) may be a better therapeutic option compared with TACE alone.

Objective

To investigate the clinical outcomes of SOR-TACE vs TACE alone for patients with recurrent intermediate-stage HCC after R0 hepatectomy with positive MVI.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this phase 3, open-label, multicenter randomized clinical trial, patients with recurrent intermediate-stage HCC and positive MVI were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio via a computerized minimization technique to either SOR-TACE treatment or TACE alone. This trial was conducted at 5 hospitals in China, and enrolled patients from October 2019 to December 2021, with a follow-up period of 24 months. Data were analyzed from June 2023 to September 2023.

Interventions

Randomization to on-demand TACE (conventional TACE: doxorubicin, 50 mg, mixed with lipiodol and gelatin sponge particles [diameter: 150-350 μm]; drug-eluting bead TACE: doxorubicin, 75 mg, mixed with drug-eluting particles [diameter: 100-300 μm or 300-500 μm]) (TACE group) or sorafenib, 400 mg, twice daily plus on-demand TACE (SOR-TACE group) (conventional TACE: doxorubicin, 50 mg, mixed with lipiodol and gelatin sponge particles [diameter, 150-350 μm]; drug-eluting bead TACE: doxorubicin, 75 mg, mixed with drug-eluting particles [diameter: 100-300 μm or 300-500 μm]).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was overall survival by intention-to-treat analysis. Safety was assessed in patients who received at least 1 dose of study treatment.

Results

A total of 162 patients (median [range] age, 55 [28-75] years; 151 males [93.2%]), were randomly assigned to be treated with either SOR-TACE (n = 81) or TACE alone (n = 81). The median overall survival was significantly longer in the SOR-TACE group than in the TACE group (22.2 months vs 15.1 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.55; P < .001). SOR-TACE also prolonged progression-free survival (16.2 months vs 11.8 months; HR, 0.54; P < .001), and improved the objective response rate when compared with TACE alone based on the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria (80.2% vs 58.0%; P = .002). Any grade adverse events were more common in the SOR-TACE group, but all adverse events responded well to treatment. No unexpected adverse events or treatment-related deaths occurred in this study.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this randomized clinical trial demonstrated that SOR-TACE achieved better clinical outcomes than TACE alone. These findings suggest that combined treatment should be used for patients with recurrent intermediate-stage HCC after R0 hepatectomy with positive MVI.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04103398

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the efficacy and safety of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib vs TACE alone for patients with recurrent intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common malignant neoplasm that ranks third among global tumor-related deaths.1 Although curative liver resection is commonly recommended as the primary treatment for HCC at early stages, the postoperative recurrence rate remains high, with a 5-year recurrence rate of approximately 70%.2 About 30% of patients with recurrent HCC are diagnosed at an intermediate stage (defined as multifocal recurrent HCC confined to the liver without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread), which has a poor prognosis.3 Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is recommended for patients with intermediate-stage or multifocal HCC in most guidelines for HCC management,4,5,6 and is also widely used in treating patients with recurrent HCC.7,8,9 The 2018 European Association for the Study of the Liver HCC guidelines suggest that TACE is the optimal treatment. However, when treated by TACE, the objective response rate (ORR) of the tumor remained only at 52.5% and the 5-year tumor recurrence rate was higher than 70%.10 Several major factors were found to be associated with the effectiveness of TACE, including microvascular invasion (MVI) detected in specimens at initial liver resection. Studies consistently have shown that MVI detected in primary HCC resection correlates with poorer differentiation of recurrent tumors and poorer prognosis for patients after HCC recurrence.11,12 The reported 1-year and 2-year disease-free survival rates of recurrent intermediate HCC in these patients range from 50% to 60% and 30% to 40%, respectively. These survival rates are significantly shorter than that for patients with recurrent HCC without MVI.13,14 More effective treatments for these patients are urgently needed, but the optimal strategies to treat these tumors remain undefined.15

Sorafenib, the first-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is commonly used as a standard systematic therapy for patients with HCC.4,5 With its ability to inhibit the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor, induced by TACE, and the synergistic effect of sorafenib plus TACE (SOR-TACE), combined treatment may be effective in prolonging progression-free survival (PFS) for patients with unresectable HCC when compared with TACE alone.16 Several retrospective studies also reported on the superiority of SOR-TACE to TACE alone in the survival of patients with recurrent HCC.17,18 Recently, we retrospectively compared the efficacy and safety between SOR-TACE and TACE alone in patients with recurrent intermediate HCC whose specimens in the initial primary liver resection were positive for MVI.19 SOR-TACE achieved better overall survival (OS) (17.2 months vs 12.1 months) and a 1-year OS rate (73.9% vs 50.3%) when compared with TACE alone. Only mild adverse events (AEs) were reported with the combination treatment. These encouraging results prompted us to develop a prospective trial to validate the survival benefit of SOR-TACE vs TACE in patients with recurrent intermediate HCC. Thus, this randomized clinical trial was conducted, aiming to assess the effectiveness and safety of SOR-TACE vs TACE alone for patients with recurrent intermediate-stage HCC positive for MVI.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This phase 3, open-label, multicenter, randomized comparative trial was performed from October 2019 to December 2021 at 5 hospitals in China (trial protocol in Supplement 1). Eligible patients were screened and randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to be treated with either SOR-TACE or TACE monotherapy by using a computerized minimization technique for randomization. Randomized stratification factors included major tumor size (<5 cm vs ≥5 cm) and tumor number (≤3 tumors vs >3 tumors). The study schema is presented in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2. Each site’s institutional review board approved the study, and all patients provided written informed consent to participate. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline was followed.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients with recurrent HCC were eligible for inclusion in this study if they met the following criteria: (1) between 18 and 75 years of age; (2) first tumor recurrence following R0 surgical resection; (3) histologically confirmed MVI in specimens in the initial HCC resection; (4) recurrent HCC lesions confirmed by imaging (2 to 3 lesions with at least 1 lesion greater than 3 cm in diameter or more than 3 lesions of any diameter); (5) tumor burden of 50% or less without distant metastasis and macroscopic vascular invasion; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score of 0 (fully active) or 1 (restricted in strenuous activity but ambulatory); (6) Child-Pugh class A (well-compensated disease); (7) life expectancy of more than 3 months; and (8) satisfactory blood, liver, and kidney function parameters (neutrophil count of at least 1500/μL [1.5 × 109/L]; platelet count of at least 60 × 103/μL [60 × 109/L]; hemoglobin concentration of at least 9 g/dL [90 g/L]; serum albumin concentration of at least 3 g/dL [30 g/L]; bilirubin of 1.5 times the upper limit of normal or less, mg/dL [multiply by 17.104 to convert to µmol/L]; aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels of less than 5 times the upper limit of normal, IU/L [multiply by 0.0167 to convert to µkat/L]; albumin levels of less than 4 times the upper limit of normal, g/dL [multiply by 10 to convert to g/L]; extended prothrombin time not exceeding 6 seconds of the upper limit of normal; and creatinine levels of less than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, mg/dL [multiply by 88.4 to convert to µmol/L]). MVI was defined as positive when the tumor cell clusters lined by endothelium within a vascular space of the surrounding hepatic tissues were visible only at microscopy (detailed description in the eMethods in Supplement 2).20

Exclusion Criteria

All exclusion criteria are listed in the trial protocol (Supplement 1). A few of these criteria are as follows: preoperative imaging displaying diffuse infiltrative lesion in the liver, or invasion of the primary branch of the common bile duct; history of hepatic encephalopathy, refractory ascites, or bleeding esophageal varices; and presence of contraindications for TACE, such as portosystemic shunt, hepatofugal flow, and obvious atherosclerosis.

Procedures

In the SOR-TACE group, patients received sorafenib, 400 mg orally, twice daily within 3 days of randomization, and the first session of TACE was given 1 day after oral administration of sorafenib. In the TACE group, the first session of TACE was performed within 3 days after randomization. In both groups, TACE was repeated on demand if incomplete tumor necrosis or tumor regrowth occurred with adequate liver function. Only one of the following TACE approaches was allowed during initial or repeated TACE: conventional TACE or drug-eluting beads TACE. Interventional radiologists selected the TACE approach. A detailed description of the intervention is included in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Efficacy and Safety Analyses

The primary end point was OS (defined as the date of randomization to death from any cause). The secondary end points were PFS (defined as the date from randomization until progression or death from any cause), ORR (the proportion of complete response or partial response based on the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [mRECIST] and RECIST, version 1.121,22), and AEs assessed using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03.23 Detailed descriptions of the efficacy and safety analyses are included in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was calculated assuming that the median OS in the TACE group was 12 months, based on a previous study by Peng et al,19 and that the SOR-TACE group had an improved OS of 20 months, with a corresponding hazard ratio (HR) of 0.6. With a 2-sided type 1 error of .05 and power of 80%, a total sample size of 162 patients, a follow-up period of more than 24 months for all patients, and a total study duration of 48 months were required with an estimated 5% loss of follow-up and a noncompliance rate to target 122 OS events.

The primary efficacy analysis was performed in the intention-to-treat population. The safety analysis comprised all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of study treatment. Survival outcomes were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared via the log-rank test. HRs were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model. In addition, a stratified log-rank test was performed using the prespecified random assignment stratification factors, and stratified HRs were estimated to form part of the primary analysis. Any factors with P < .10 in the univariate analysis were candidates for entry into the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. Statistical significance of differences in tumor response and safety variables between subgroups were evaluated using the Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact test. All significance testing was 2-sided with P < .05 considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using STATA, version 15.0 (StataCorp), and R statistical software, version 4.0.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing). Data were analyzed from June 2023 to September 2023.

Results

Patient Characteristics and Treatment Randomization

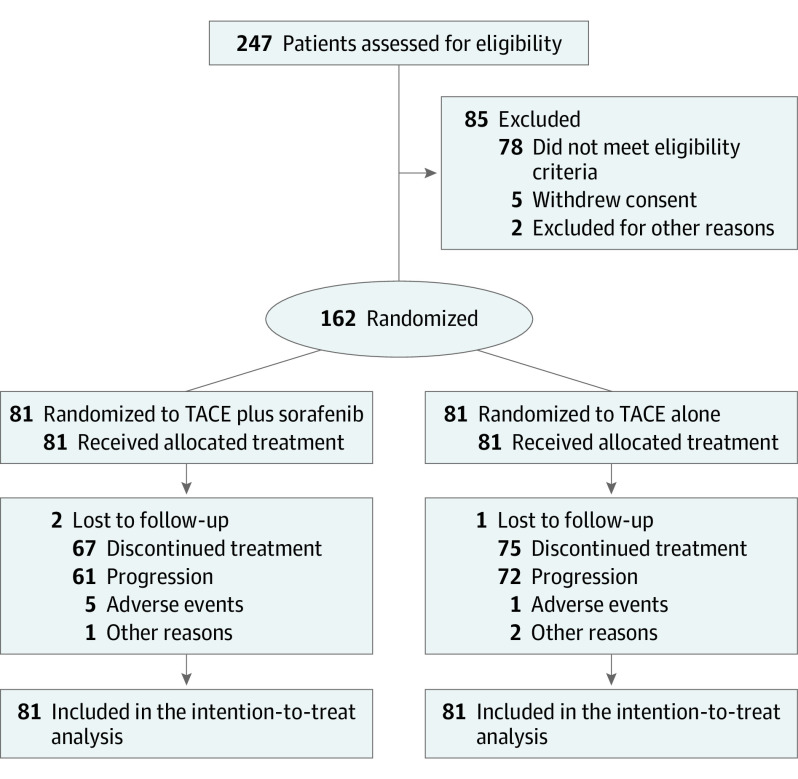

Between October 2019 and December 2021, 162 patients (median [range] age, 55 [28-75] years; 151 males [93.2%]) were randomly assigned to be treated with either SOR-TACE (n = 81) or TACE alone (n = 81) (Figure 1). The survival statistics were censored on May 30, 2023. The 2 groups of patients had similar baseline characteristics (Table 1). The majority of patients had hepatitis B virus infection (76 patients [93.8%] in the SOR-TACE group and 72 patients [88.9%] in the TACE group). The median (IQR) interval between initial liver resection and recurrence was 8.5 (4.6-18.8) months in the SOR-TACE group and 7.2 (3.7-16.7) months in the TACE group (P = .16). The baseline characteristics before the initial curative treatment are reported in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Figure 1. Trial Flow Diagram.

The diagram shows the flow of 162 patients assigned to transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib (n = 81) or TACE alone (n = 81) through the TREAT randomized clinical trial.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics for Patients Treated With SOR-TACE vs TACE Alone.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SOR-TACE group (n = 81) | TACE group (n = 81) | Total (N = 162) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 54 (47-63) | 58 (44-66) | 55 (45-65) |

| <50 | 31 (38.3) | 28 (34.6) | 59 (36.4) |

| ≥50 | 50 (61.7) | 53 (65.4) | 103 (63.6) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 9 (11.1) | 2 (2.5) | 11 (6.8) |

| Male | 72 (88.9) | 79 (97.5) | 151 (93.2) |

| Origin | |||

| Hepatitis B | 76 (93.8) | 72 (88.9) | 148 (91.4) |

| Hepatitis C | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.7) | 5 (3.1) |

| Other | 3 (3.7) | 6 (7.4) | 9 (5.5) |

| Cirrhosis | |||

| Yes | 50 (61.7) | 51 (63.0) | 101 (62.3) |

| No | 31 (38.3) | 30 (37.0) | 61 (37.7) |

| ECOG-PS scorea | |||

| 0 | 73 (90.1) | 71 (87.7) | 144 (88.9) |

| 1 | 8 (9.9) | 10 (12.3) | 18 (11.1) |

| α1-Fetoprotein, median (IQR), ng/mL | 36.6 (4.6-310.5) | 64.1 (4.5-1432.5) | 37.6 (4.5-633.7) |

| <400 | 61 (75.3) | 51 (63.0) | 112 (69.1) |

| ≥400 | 20 (24.7) | 30 (37.0) | 50 (30.9) |

| Functional parameters, median (IQR) | |||

| ALT, IU/L | 29 (19-38) | 28 (20-42) | 28 (19-40) |

| AST, IU/L | 30 (23-45) | 34 (27-50) | 32 (25-49) |

| ALB, g/dL | 38.1 (36.0-40.6) | 37.6 (35.0-40.8) | 37.8 (35.3-40.6) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 15.1 (9.9-21.1) | 14.3 (11.6-20.3) | 14.5 (11.1-20.9) |

| PT, s | 12.1 (11.5-12.9) | 12.3 (11.7-13.1) | 12.2 (11.6-13.0) |

| Child-Pugh scoreb | |||

| 5 | 64 (79.0) | 58 (71.6) | 122 (75.3) |

| 6 | 17 (21.0) | 23 (28.4) | 40 (24.7) |

| ALBI score, median (IQR)c | −2.49 (−2.73 to −2.22) | −2.42 (−2.72 to −2.12) | −2.46 (−2.73 to −2.19) |

| ALBI gradec | |||

| Grade 1 | 30 (37.0) | 27 (33.3) | 57 (35.2) |

| Grade 2 | 51 (63.0) | 54 (66.7) | 105 (64.8) |

| No. of tumors | |||

| ≤3 | 7 (8.6) | 6 (7.4) | 13 (8.0) |

| >3 | 74 (91.4) | 75 (92.6) | 149 (92.0) |

| Tumor size, median (IQR), cm | 2.4 (1.6-4.7) | 2.6 (1.7-4.3) | 2.5 (1.7-4.3) |

| <5 cm | 64 (79.0) | 67 (82.7) | 131 (80.9) |

| ≥5 cm | 17 (21.0) | 14 (17.3) | 31 (19.2) |

| Recurrent interval, median (IQR), mod | 8.5 (4.6-18.8) | 7.2 (3.7-16.7) | 7.9 (3.7-18.2) |

| ≤1 y | 46 (56.8) | 52 (64.2) | 98 (60.5) |

| >1 y | 35 (43.2) | 29 (35.8) | 64 (39.5) |

| TACE sessions, median (IQR) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (1-3) |

| 1 | 32 (39.5) | 22 (27.2) | 54 (33.3) |

| 2 | 14 (17.3) | 29 (35.8) | 43 (26.5) |

| ≥3 | 35 (43.2) | 30 (37.0) | 65 (40.1) |

Abbreviations: ALB, albumin; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin score; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; PT, prothrombin time (international ratio); SOR-TACE, transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

SI conversion factors: To convert α1-Fetoprotein to µg/L, multiply by 1; ALB to g/L, multiply by 10; bilirubin to µmol/L, multiply by 17.104; ALT and AST to µkat/L, multiply by 0.0167; and creatinine to µmol/L, multiply by 88.4.

ECOG-PS score of 0 indicates the patient is fully active, and 1 indicates the patient is restricted in strenuous activity but ambulatory.

A total Child-Pugh score of 5 to 6 is considered Child-Pugh class A (well-compensated disease).

An ALBI score of −2.60 or less indicates from 18.5 to 85.6 months median survival (grade 1); an ALBI score between −2.60 and −1.39 indicates median survival between 5.3 and 46.5 months (grade 2).

Recurrent interval indicates the time interval between the initial hepatectomy and tumor recurrence.

The median (range) duration of sorafenib treatment in the SOR-TACE group was 16.2 (3.5-43.0) months, and the mean (SD) duration was 19.5 (10.2) months. The median (range) daily dose of sorafenib was 545.5 (317.2-800.0) mg (TACE administration in both groups reported in eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Patients in the SOR-TACE group underwent 214 TACE treatments, and the median (range) number of TACE sessions per patient was 2 (1-3) sessions. Patients in the TACE group underwent 198 TACE treatments, and the median (range) number of TACE sessions per patient was 2 (1-3) sessions. Overall, 67 patients (82.7%) and 75 patients (92.6%) in the SOR-TACE and TACE groups, respectively, underwent subsequent therapies after discontinuation of the original treatments, respectively (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Efficacy

Response variables in both treatment groups were compared with RECIST, version 1.1, and mRECIST (Table 2). The ORR was 77.8% in the SOR-TACE group and 53.1% in the TACE group based on RECIST, version 1.1 (P = .001), while the ORR was 80.2% in the SOR-TACE group and 58.0% in the TACE group based on the mRECIST (P = .002).

Table 2. Best Response Rates.

| Response variable | RECIST, version 1.1, No. (%) | mRECIST, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOR-TACE (n = 81) | TACE (n = 81) | P value | SOR-TACE (n = 81) | TACE (n = 81) | P value | |

| Complete response | 25 (30.7) | 14 (17.3) | .04 | 30 (37.0) | 17 (21.0) | .02 |

| Partial response | 38 (46.9) | 29 (35.8) | .15 | 35 (43.2) | 30 (37.0) | .42 |

| Stable disease | 10 (12.3) | 27 (33.3) | .001 | 9 (11.1) | 25 (30.9) | .002 |

| Progressive disease | 8 (9.9) | 11 (13.6) | .46 | 7 (8.6) | 9 (11.1) | .60 |

| Objective response rate | 63 (77.8) | 43 (53.1) | .001 | 65 (80.2) | 47 (58.0) | .002 |

| Disease control ratea | 73 (90.1) | 70 (86.4) | .46 | 74 (91.4) | 72 (88.9) | .60 |

Abbreviations: mRECIST, modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; SOR-TACE, transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

The disease control rate was defined as the proportion of patients with complete response plus partial response and stable disease based on the RECIST, version 1.1, and mRECIST criteria.

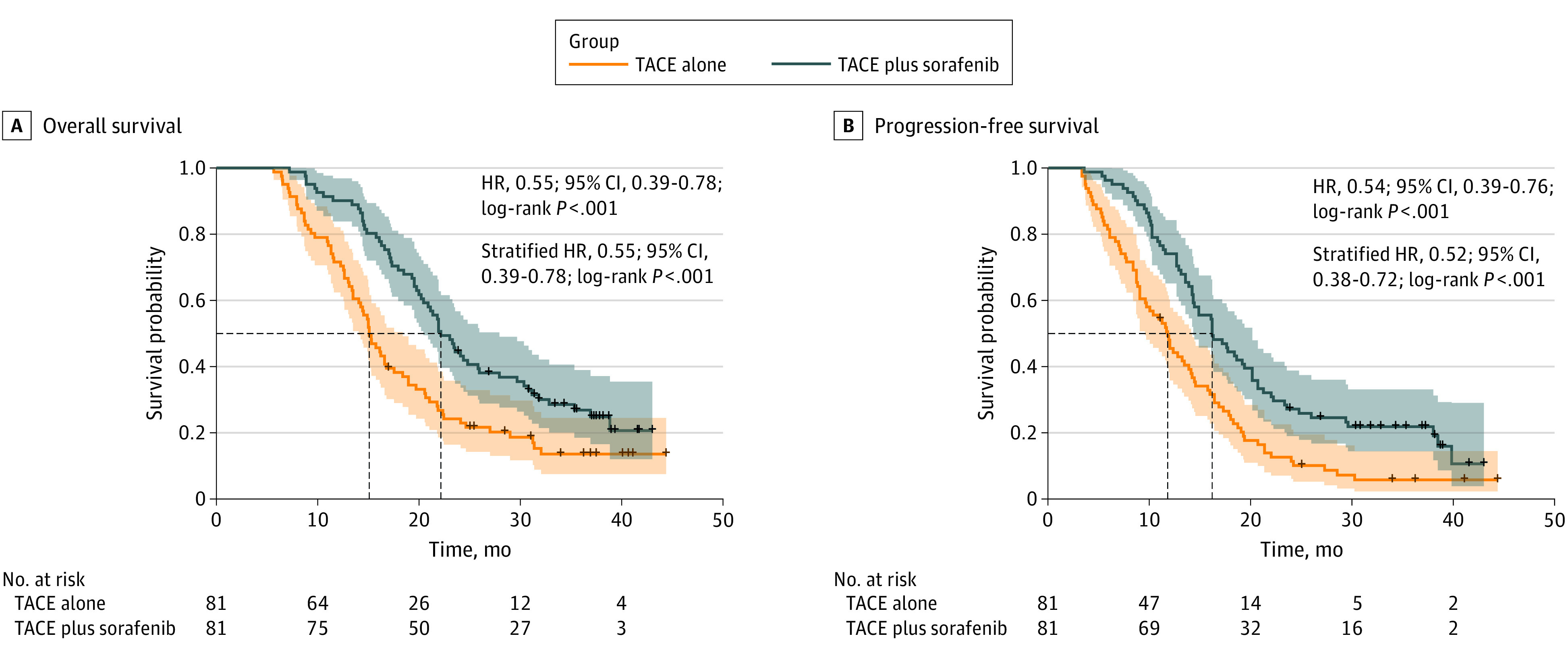

On a median follow-up of 37.5 months (95% CI, 36.4-38.6 months) in the SOR-TACE group and 36.9 months (95% CI, 33.3-40.5 months) in the TACE group, 128 deaths had occurred with 60 patients (74.1%) in the SOR-TACE group and 68 patients (84.0%) in the TACE group. The median OS was 22.2 months (95% CI, 20.4-27.9) for the SOR-TACE group and 15.1 months (95% CI, 14.0-18.4) for the TACE group. The corresponding HR for OS was 0.55 (95% CI, 0.39-0.78; P < .001), and the stratified HR was 0.55 (95% CI, 0.39-0.78; P < .001) (Figure 2A). The 12-month, 24-month, and 36-month OS rates were 90.1%, 44.4%, and 26.9% in the SOR-TACE group, and 71.6%, 24.2%, and 13.6% in the TACE group, respectively.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Patients Treated With Transarterial Chemoembolization (TACE) Plus Sorafenib vs TACE Alone.

The figure shows survival curves for 2 survival outcomes in the 2 treatment groups. The dashed lines indicate median overall survival and median progression-free survival. The shaded areas indicate 95% CIs; HR indicates hazard ratio.

At the time this study was censored, 66 patients (81.5%) in the SOR-TACE group and 75 patients (92.6%) in the TACE group experienced disease progression or death. The median PFS was significantly longer in the SOR-TACE group at 16.2 months (95% CI, 14.3-20.1) than in the TACE group at 11.8 months (95% CI, 9.6-14.2; HR, 0.54 [95% CI, 0.39-0.76]; P < .001; stratified HR, 0.52 [95% CI, 0.38-0.72]; P < .001) (Figure 2B). The 6-month, 12-month, and 24-month PFS rates were 96.3%, 74.1%, and 27.2% for the SOR-TACE group, and 81.5%, 48.0%, and 11.4% for the TACE group, respectively.

When the survival outcomes in both groups were compared between patients who underwent conventional TACE or drug-eluting beads TACE, the median OS, PFS, and local tumor response rate were comparable (eFigure 2 and eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Forest plot analysis of prognostic risk factors showed that SOR-TACE was associated with longer OS and PFS when compared with TACE in the subgroup populations with most of the predefined variables, including age 50 years and older, α1-fetoprotein of less than 400 ng/mL (400 µg/L), more than 3 tumors, tumor size of less than 5 cm (eFigures 3 and 4 in Supplement 2). Multivariable analyses revealed that tumor size (HR, 1.56 [95% CI, 1.01-2.39]; P = .04) and treatment allocation (HR, 0.56 [95% CI, 0.40-0.81]; P = .002) were independent risk factors for OS. Additionally, tumor size (HR, 1.60 [95% CI, 1.07-2.41]; P = .02) and treatment allocation (HR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.39-0.78]; P = .001; eTable 5 in Supplement 2) were identified as independent risk factors for PFS.

Safety

All grades of treatment-emergent and drug-related AEs are listed in Table 3. No unexpected AEs and no treatment-related deaths occurred in this study. Any grade AEs were more common in the SOR-TACE group, but all the AEs were manageable with treatment. The incidence of AEs relating to postembolization syndrome, including abdominal pain, increase in liver enzymes, nausea, and fever, were similar in both groups. The most common grade 3 or 4 AEs in both groups were similar, including increased alanine aminotransferase (16 patients [19.8%] vs 16 patients [19.8%]; P > .99) and increased aspartate aminotransferase (19 patients [23.5%] vs 15 patients [18.5%]; P = .56). Sorafenib-related grade 3 or 4 AEs included hand-foot skin reaction (10 patients [12.3%] in SOR-TACE vs 0 patients in TACE alone; P < .001) and hypertension (11 patients [13.6%] in SOR-TACE vs 0 patients in TACE alone; P < .001). Patients recovered from all AEs after treatment or dose reduction. Twenty-one patients (25.9%) in the SOR-TACE group and 16 patients (19.8%) in the TACE group experienced acute deterioration of albumin-bilirubin grade within 1 week following TACE (P = .35). In the SOR-TACE group, 56 patients (69.1%) and 38 patients (46.9%) required dose reduction and/or sorafenib interruption, respectively. Causes of dose reduction and interruption of sorafenib due to AEs are reported in eTable 6 in Supplement 2.

Table 3. Adverse Events.

| Adverse event | Any grade, No. (%) | Grade 3-4, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOR-TACE (n = 81) | TACE (n = 81) | P value | SOR-TACE (n = 81) | TACE (n = 81) | P value | |

| ALT increased | 74 (91.4) | 72 (88.9) | .79 | 16 (19.8) | 16 (19.8) | >.99 |

| AST increased | 73 (90.1) | 63 (77.8) | .05 | 19 (23.5) | 15 (18.5) | .56 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 44 (54.3) | 42 (51.9) | .88 | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.7) | >.99 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 45 (55.6) | 42 (51.9) | .75 | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | >.99 |

| Hand-foot skin reaction | 43 (53.1) | 0 | <.001 | 10 (12.3) | 0 | .001 |

| Abdominal pain | 37 (45.7) | 39 (48.1) | .88 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | >.99 |

| Nausea | 21 (25.9) | 23 (28.4) | .86 | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.5) | >.99 |

| Diarrhea | 38 (46.9) | 11 (13.6) | <.001 | 5 (6.2) | 2 (2.5) | .44 |

| Fever | 14 (17.3) | 15 (18.5) | >.99 | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Hypertension | 31 (38.3) | 3 (3.7) | <.001 | 11 (13.6) | 0 | <.001 |

| Alopecia | 4 (4.9) | 1 (1.2) | .37 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | >.99 |

| Ascites | 6 (7.4) | 7 (8.6) | >.99 | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Vomiting | 14 (17.3) | 13 (16.0) | >.99 | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | >.99 |

| Fatigue | 20 (24.7) | 10 (12.3) | .07 | 2 (2.5) | 0 | .50 |

| Dysphonia | 12 (14.8) | 0 | <.001 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | >.99 |

| Anemia | 38 (46.9) | 7 (8.6) | <.001 | 7 (8.6) | 2 (2.5) | .17 |

| Decreased WBC count | 15 (18.5) | 13 (16.0) | .84 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | >.99 |

| Decreased appetite | 28 (34.6) | 23 (28.4) | .50 | 3 (3.7) | 0 | .25 |

| Weight decreased | 30 (37.0) | 23 (28.4) | .32 | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Rash | 20 (24.7) | 0 | <.001 | 3 (3.7) | 0 | .25 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; SOR-TACE, transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; WBC, white blood cell.

Discussion

This randomized comparative phase 3 trial showed that SOR-TACE achieved significantly better survival outcomes than TACE alone in patients with recurrent intermediate-stage HCC after R0 hepatectomy with specimens showing positive MVI. These improved survival outcomes are consistent across most of the clinical subgroups, further confirming the superiority of SOR-TACE to TACE alone, as reported in a previous retrospective study by Peng et al.19 In addition, this study observed acceptable safety levels for SOR-TACE treatment, which patients generally tolerated well.

Although most guidelines recommend TACE as an optimal treatment option for recurrent HCC as well as for unresectable primary HCC, recurrent HCC is generally regarded as more aggressive than primary HCC by exhibiting increased rates of tumor proliferation and angiogenesis. Studies have also indicated that tumor doubling time for recurrent HCC treated with TACE is shorter when compared with that of primary HCC,24 and intrahepatic recurrence of HCC after R0 hepatectomy is more frequent in patients with MVI-positive HCC.25 Thus, the combined therapy of SOR-TACE has been widely used in treating recurrent HCC to achieve better tumor control. A retrospective study by Yao et al26 on multifocal HCC showed significant improvement in OS by using combined SOR-TACE for treating patients with recurrent HCC when compared with TACE monotherapy (17.5 months vs 11.0 months). Furthermore, another study by Peng et al19 demonstrated that only patients with recurrent HCC and confirmed MVI could benefit from the combined therapy with prolonged OS (17.2 months vs 12.1 months). The results of the current prospective randomized comparative study further confirmed the beneficial effect of this combination therapy compared with TACE. The positive results might relate to strict enforcement of full sorafenib use and its administration 1 day before TACE.

The survival benefit of SOR-TACE vs TACE alone in our study can be explained in several ways. First, the presence of MVI is well recognized as a risk factor for recurrence and poor prognosis, and it is associated with poorer tumor differentiation and aggressive behavior of recurrent HCCs.12,14,27,28 Thus, for a patient after R0 hepatectomy with positive MVI, post–TACE angiogenesis might cause tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis more predominantly than in those without MVI. Combined SOR-TACE might play a more important role in improving long-term survival in these patients. Second, MVI-positive tumors are known to be associated with highly proliferative and metastatic features. The antiproliferative effect of sorafenib could significantly help to better control the tumors, whereas, for MVI-negative tumors, this effect might be less obvious.29,30 Third, most guidelines recommend TACE to treat unresectable or intermediate HCC. TACE can provide survival benefits in only approximately 10% of all patients in achieving complete response with repeated TACE sessions.31 For this low rate of complete response in patients with HCC undergoing TACE, studies have reported that the expressions of vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor may increase with incomplete embolization, contributing to poor long-term survival outcomes in these patients.32,33 Thus, the concurrent use of sorafenib, which is an inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors, should give a good synergistic effect to TACE in treating these patients. Several studies have suggested that patients with HCC and MVI who underwent R0 hepatectomy could benefit from adjuvant sorafenib.34,35,36 The results of our study showed that the ORR of the SOR-TACE group was significantly higher than that of the TACE group (80.2% vs 58.0%), indicating that the combined therapy indeed helped to control tumor progression.

Our current study also observed SOR-TACE to be clinically feasible and safe. Although many AEs were more frequent in the SOR-TACE group than the TACE group, all AEs were moderate and manageable, and the rates of grade 3 and 4 AEs were relatively low. The incidence of abdominal pain, nausea, and fever, which were generally considered to relate to postembolization syndrome, were similar in the 2 groups, suggesting that sorafenib had little and manageable effects in increasing complications caused by TACE.

Limitations

This study used an open-label design. To minimize the introduction of any potential bias, the results were confirmed by a masked independent imaging review. The study was conducted in an endemic region where the primary cause of HCC is chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Consequently, the generalizability of the findings to Western countries, where the primary cause of HCC is predominantly attributed to hepatitis C virus infection, requires further investigation. Further investigations on the combination of more modern systemic therapies and different types of hepatic arterial therapies are needed.

Conclusions

This randomized clinical trial suggested that SOR-TACE is a safe and effective treatment for patients with recurrent intermediate-stage HCC after R0 initial hepatectomy with positive MVI. The combined treatment was superior to TACE alone in improving OS, PFS, and ORR, with only moderate and manageable AEs. Thus, SOR-TACE therapy has the potential to be used effectively in these patients.

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Characteristics before initial curative treatment

eTable 2. Characteristics of TACE administration in two groups

eTable 3. Number of patients who received subsequent treatments after discontinuation

eTable 4. Best response after treatment of patients receiving cTACE and DEB-TACE

eTable 5. Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with overall survival and progression-free survival after treatment

eTable 6. Adverse events leading to sorafenib dose reduction or interruption

eFigure 1. Study schema

eFigure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival and progression-free survival for patients who received cTACE or DEB-TACE

eFigure 3. Forest plots of overall survival

eFigure 4. Forest plots of progression-free survival

eFigure 5. Imaging follow-up schema

eMethods. Additional methods

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE Study. Liver Int. 2015;35(9):2155-2166. doi: 10.1111/liv.12818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Tanaka E, et al. Risk factors contributing to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. J Hepatol. 2003;38(2):200-207. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00360-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182-236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):358-380. doi: 10.1002/hep.29086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson AB, D’Angelica MI, Abbott DE, et al. Hepatobiliary cancers, version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(5):541-565. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JW, Park JY, Ahn SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of transarterial chemoembolization in recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after curative surgical resection. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(6):564-569. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181967da0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho CM, Lee PH, Shau WY, Ho MC, Wu YM, Hu RH. Survival in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after primary hepatectomy: comparative effectiveness of treatment modalities. Surgery. 2012;151(5):700-709. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, Liu G, Li J, et al. Early intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy treated with re-hepatectomy, ablation or chemoembolization: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(2):236-242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lencioni R, de Baere T, Soulen MC, Rilling WS, Geschwind JF. Lipiodol transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of efficacy and safety data. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):106-116. doi: 10.1002/hep.28453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou YF, Li B, Wei YG, et al. Second hepatectomy improves survival in patients with microvascular invasive hepatocellular carcinoma meeting the Milan criteria. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(48):e2070. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meniconi RL, Komatsu S, Perdigao F, Boëlle PY, Soubrane O, Scatton O. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a Western strategy that emphasizes the impact of pathologic profile of the first resection. Surgery. 2015;157(3):454-462. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roayaie S, Blume IN, Thung SN, et al. A system of classifying microvascular invasion to predict outcome after resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):850-855. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim KC, Chow PK, Allen JC, et al. Microvascular invasion is a better predictor of tumor recurrence and overall survival following surgical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma compared to the Milan criteria. Ann Surg. 2011;254(1):108-113. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821ad884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin YJ, Lee JW, Lee OH, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization versus surgery/radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma with or without microvascular invasion. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(5):1056-1064. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudo M, Ueshima K, Ikeda M, et al. Final results of TACTICS: a randomized, prospective trial comparing transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib to transarterial chemoembolization alone in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022;11(4):354-367. doi: 10.1159/000522547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan X, Zhai X, Yan Z, et al. Retrospective analysis of transarterial chemoembolization and sorafenib in Chinese patients with unresectable and recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(50):83806-83816. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Cai L, Fang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Front Oncol. 2023;12:1101351. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1101351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng Z, Chen S, Xiao H, et al. Microvascular invasion as a predictor of response to treatment with sorafenib and transarterial chemoembolization for recurrent intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiology. 2019;292(1):237-247. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodríguez-Perálvarez M, Luong TV, Andreana L, Meyer T, Dhillon AP, Burroughs AK. A systematic review of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnostic and prognostic variability. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(1):325-339. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2513-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):52-60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) (version 4.0). Published May 28, 2009. Accessed March 16, 2015. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf

- 24.Tezuka M, Hayashi K, Kubota K, et al. Growth rate of locally recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization: comparing the growth rate of locally recurrent tumor with that of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(3):783-788. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9537-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, He XD, Yao N, Liang WJ, Zhang YC. A meta-analysis of adjuvant therapy after potentially curative treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27(6):351-363. doi: 10.1155/2013/417894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao W, Xue M, Lu M, et al. Diffuse recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection: transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) combined with sorafenib versus TACE monotherapy. Front Oncol. 2020;10:574668. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.574668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau WY, Lai EC, Lau SH. The current role of neoadjuvant/adjuvant/chemoprevention therapy in partial hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8(2):124-133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du M, Chen L, Zhao J, et al. Microvascular invasion (MVI) is a poorer prognostic predictor for small hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z, Hu J, Qiu SJ, et al. An investigation of the effect of sorafenib on tumour growth and recurrence after liver cancer resection in nude mice independent of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase levels. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20(8):1039-1045. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.588598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng YX, Wang T, Deng YZ, et al. Sorafenib suppresses postsurgical recurrence and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma in an orthotopic mouse model. Hepatology. 2011;53(2):483-492. doi: 10.1002/hep.24075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin YJ, Chung YH, Kim JA, et al. Predisposing factors of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence following complete remission in response to transarterial chemoembolization. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(6):1758-1765. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2562-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Shi Y, Jiang CY, et al. Coexpression of PDGFR-alpha, PDGFR-beta and VEGF as a prognostic factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Biol Markers. 2011;26(2):108-116. doi: 10.5301/JBM.2011.8322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chao Y, Li CP, Chau GY, et al. Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and angiogenin in patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(4):355-362. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang Y, Zhang Z, Zhou Y, Yang J, Hu K, Wang Z. Should we apply sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with microvascular invasion after curative hepatectomy. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:541-548. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S187357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang XP, Chai ZT, Gao YZ, et al. Postoperative adjuvant sorafenib improves survival outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with microvascular invasion after R0 liver resection: a propensity score matching analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21(12):1687-1696. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2019.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu W, Tong Z. Sorafenib in the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and microvascular infiltration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(8):300060520946872. doi: 10.1177/0300060520946872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Characteristics before initial curative treatment

eTable 2. Characteristics of TACE administration in two groups

eTable 3. Number of patients who received subsequent treatments after discontinuation

eTable 4. Best response after treatment of patients receiving cTACE and DEB-TACE

eTable 5. Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with overall survival and progression-free survival after treatment

eTable 6. Adverse events leading to sorafenib dose reduction or interruption

eFigure 1. Study schema

eFigure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival and progression-free survival for patients who received cTACE or DEB-TACE

eFigure 3. Forest plots of overall survival

eFigure 4. Forest plots of progression-free survival

eFigure 5. Imaging follow-up schema

eMethods. Additional methods

Data sharing statement