Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

Keywords: Pain, Suffering, Definition, Natural language processing, Machine learning, ChatGPT, GPT-3, Topic modeling, LDA

Abstract

Understanding, measuring, and mitigating pain-related suffering is a key challenge for both clinical care and pain research. However, there is no consensus on what exactly the concept of pain-related suffering includes, and it is often not precisely operationalized in empirical studies. Here, we (1) systematically review the conceptualization of pain-related suffering in the existing literature, (2) develop a definition and a conceptual framework, and (3) use machine learning to cross-validate the results. We identified 111 articles in a systematic search of Web of Science, PubMed, PsychINFO, and PhilPapers for peer-reviewed articles containing conceptual contributions about the experience of pain-related suffering. We developed a new procedure for extracting and synthesizing study information based on the cross-validation of qualitative analysis with an artificial intelligence–based approach grounded in large language models and topic modeling. We derived a definition from the literature that is representative of current theoretical views and describes pain-related suffering as a severely negative, complex, and dynamic experience in response to a perceived threat to an individual's integrity as a self and identity as a person. We also offer a conceptual framework of pain-related suffering distinguishing 8 dimensions: social, physical, personal, spiritual, existential, cultural, cognitive, and affective. Our data show that pain-related suffering is a multidimensional phenomenon that is closely related to but distinct from pain itself. The present analysis provides a roadmap for further theoretical and empirical development.

1. Introduction

Suffering in the context of physical pain is one of the key challenges for both clinical care and pain research.29,86,91 Alleviating suffering and pain is considered central to medical practice. However, there is currently no consensus on how to conceptualize suffering, whether it is related to pain or to diseases in general.

Most frequently, pain related-suffering is understood along the lines of Eric Cassell's definition of suffering as “the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person.”20 However, although this definition is widely considered as a milestone and merits recognition for introducing the concept of suffering into pain research and clinical practice, it has repeatedly been criticized for excluding certain populations such as preverbal infants89 and for lacking clarity.17 Other definitions have not addressed the experience of pain-related suffering in its full width and focused on psychological95,98 or sociological aspects.22,40,53 The definition of pain-related suffering remains a topic of ongoing disagreement, and the creation of measurements that reliably capture its multifaceted nature remains a challenge.

There is no established instrument to measure pain-related suffering in the clinical context, and in a recent review of existing instruments, most have been criticized for severe methodological shortcomings.50 An exception is the approach of Büchi and Sensky16 to measure pain-related suffering nonverbally, with a pictogram representing pain and its impact on the intactness of the self, which is inspired by Cassell definition. However, it has been stressed by various authors that pain-related suffering is a multidimensional experience,30,63,83 and although a pictorial representation might be a valuable approximation, it cannot replace a differentiated measurement of different dimensions of pain-related suffering.

Furthermore, it appears that different empirical studies have measured different constructs under the label “pain-related suffering.” For instance, Wade et al.95 operationalized pain-related suffering using 5 visual analogue scales measuring pain-related depression, anxiety, frustration, fear, and anger. By contrast, Baines and Norlander4 measured pain-related suffering by directly asking patients to indicate the extent of their own suffering in different areas (such as spiritual distress or concern for loved ones). This illustrates the multidimensional character of pain-related suffering and the importance of a definition that integrates its distinct but interrelated facets.

To sum up, conceptual models remain controversial and have not been operationalized systematically, whereas existing measurements lack theoretical underpinning. Both conceptual and empirical approaches to pain-related suffering thus far fail to address its multidimensional character. It is crucial to establish a comprehensive and integrative definition of pain-related suffering that adequately reflects its multifaceted nature and enables the creation of instruments that can effectively measure its different dimensions.

The current study develops a definition and a conceptual framework that reflects all important theoretical views on pain-related suffering and can be operationalized for empirical validation. We (1) systematically searched the existing literature for conceptualizations of pain-related suffering, (2) used manual qualitative research methods to synthesize the literature into an integrative definition and to develop a multidimensional conceptual framework of pain-related suffering, and finally (3) used a machine learning approach to cross-validate both the conceptual framework and the integrative definition. Accordingly, our first research question is how pain-related suffering can be defined according to the current literature. Our second research question is how pain-related suffering can be described in a multidimensional conceptual framework.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

This study is based on a systematic review and uses a combination of manual qualitative analysis and natural language processing to examine the concept of pain-related suffering in the current literature. In the first step, a transdisciplinary systematic literature search was conducted to identify relevant studies on pain-related suffering. In the second step, a manual systematic data extraction of verbatim quotations with relevant information for the conceptualization of pain-related suffering was conducted. The verbatim quotations were translated into key words, which served as a basis for (1) the derivation of essential aspects of pain-related suffering that were mentioned across different definitions, as well as for (2) the identification of the different dimensions of pain-related suffering. In the third step, natural language processing was used to cross-validate the results. Topic modeling11 was applied to the text corpus to cross-validate the different dimensions of pain-related suffering identified in the second step. To cross-validate the integrative definition of pain-related suffering obtained in the second step, we used the generative pretrained transformer large language models, GPT-3.569 and GPT-3.14 The procedure and analytical plan of the current study were predesigned. A detailed description of protocol is available from the authors upon request. The review was not preregistered.

2.2. Step 1: systematic search

This review was performed and reported according to the recommendations of the PRISMA statement70 when appropriate. We searched Web of Science, PubMed, PsychINFO, and PhilPapers. The cutoff date of the search was September 7, 2021. In addition, a citation search on the included articles was performed. The search strings were adapted for each database (see Appendix A, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13). Two reviewers (N.N.S. and a scientific assistant) independently scanned the titles and abstracts of eligible studies and, in a second step, the full text articles, to determine whether the articles met the selection criteria. Disagreements between the 2 reviewers were resolved by discussion, and if agreements could not be achieved, a third reviewer was consulted (J.T.). Study selection was performed using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia).

We selected all studies that focused on the conceptualization of pain-related suffering in the context of physical pain. To be included, an article had to (1) use the term “suffering” in a conceptual way, which we took to be the case if and only if this article specified an answer to at least 3 of 14 predefined conceptual questions in our data extraction form (see Appendix D and E, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13). In addition, the article also had to (2) discuss physical pain, or it had to be evident that the phenomenon of interest involved physical pain. We only included (3) peer-reviewed articles (4) published in English.

As this study focused on human suffering in the context of pain experiences, studies were excluded, if they (1) only dealt with the suffering of animals or (2) only discussed the effect of suffering on others, eg, on a caregiver. We did not exclude articles because of their date of appearance. A flow diagram of the study selection process is shown in Appendix B, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13.

2.3. Step 2: data extraction and synthesis with manual qualitative research methods

We developed a systematic procedure for manually extracting and analyzing data from the selected articles, with the goal of identifying defining aspects and dimensions across different conceptualizations of pain-related suffering. In addition to general article information (eg, author, discipline, or outcome, see Appendix D, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13), data extraction was structured by conceptual questions regarding pain-related suffering (eg, how each article defined suffering, what dimensions were specified, or what antecedents or consequences of suffering were postulated, see Appendix E, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13). Answers to these conceptual questions were extracted from the articles as verbatim quotations, which were then summarized into key words—ie, into terms or short phrases representing the aspect of suffering described in the respective quotation. The key words were used for all further analyses using the manual text processing method.

Data extraction and the summarization into key words were conducted by one of the authors trained in psychology and phenomenological philosophy (N.N.S). The summarization of verbatim quotations into key words was also conducted independently by a second author specialized in pain medicine and psychosomatics (J.T.). Disagreements were resolved in direct discussion.

2.3.1. Research question 1: how is pain-related suffering defined in current pain research?

Of the 111 selected articles, 60 explicitly provided an answer to the question “How does the article define pain-related suffering?” from our data extraction sheet. Table 1 lists these articles and the respective definitions. We identified common elements of the definitions by applying a modified version of concept analysis, a well-founded method of theory development that has already been used to examine the concept of suffering.9

Table 1.

Definitions of pain-related suffering found in the literature.

| Author (Year) | Discipline | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Adunsky (2008) | Palliative medicine | […] suffering is traditionally viewed as a state encompassing psychological distress, spiritual concerns, and various aspects of physical pain.1 |

| Aguilera (2021) | Bioethics | If S is a globally broadcast overall state of significant net negative valence, then S is a state of suffering.2 |

| Andaya (2011) | Medical ethics | […] suffering [is] defined as long-term or chronic distress.3 |

| Bellieni (2005) | Medical ethics | […] suffering is to be understood as frustration of the tendency towards fulfilment of the various aspects of our being.5 |

| Bernier (2019) | Nursing studies | […] suffering [is] defined here as the individual appraisal of a distressing experience.7 |

| Best (2015) | Psycho-oncology | […] suffering is defined as an all-encompassing, dynamic, individual phenomenon characterized by the experience of alienation, helplessness, hopelessness, and meaninglessness in the sufferer that is difficult for them to articulate. It is multidimensional […].8,9 |

| Best (2015) | Psycho-oncology | See Best (2015) |

| Boisaubin (1989) | Anaesthesiology | Suffering is experienced by individuals and arises from threats to the integrity of the individual as a complex social and psychological entity.12 |

| Broggi (2008) | Neurosurgery | […] suffering [is] pain's closely related experiential counterpart.13 |

| Brugnoli (2016) | Palliative medicine | [The different forms of suffering] are called the “total pain” […] that encompasses all of a person's physical, psychological, social, and spiritual [sic].15 |

| Bueno-Gomez (2017) | Medical ethics | Suffering is an unpleasant or even anguishing experience which can severely affect a person on a psychophysical and even existential level.17 |

| Bustan (2015) | Psychophysics | […] suffering [involves] long-term implications of pain associated with threat, loss, potential damage, and impending harm for the self [and is] the combined display of several distinctive negative emotions.18 |

| Cassell (1982) | Medical ethics | […] suffering can be defined as the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person.20 |

| Chapman (1999) | Anaesthesiology | Suffering is the perception of serious threat or damage to the self, and it emerges when a discrepancy develops between what one expected of one's self and what one does or is.21 |

| Charmaz (1983) | Sociology | […] suffering is the loss of self in chronically ill persons who observe their former self-images crumbling away without the simultaneous development of equally valued new ones.22 |

| Coulehan (2009) | Medical ethics | Suffering is the experience of distress or disharmony caused by the loss, or threatened loss, of what we most cherish.24 |

| de Medeiros (2009) | Gerontology | Suffering […] includes an individual's awareness of a threat to self through death, loss of identity, or uncertainty of the meaningfulness of one's life.28 |

| De Ridder (2021) | Neuroscience | [Suffering is] an unpleasant experience associated with negative cognitive, emotional, and autonomic response to a stimulus.29 |

| Del Giglio (2020) | Medical ethics | Suffering [is] defined as a state of undergoing pain, distress, or hardship.30 |

| Devisch (2017) | Psychosomatics | […] suffering is defined as an affective experience that is related to the language-based reflections we make about ourselves and about others.32 |

| Dildy (1996) | Nursing studies | Suffering was found to be a process directed toward regaining normalcy and consisted of three phases: disintegration of self; the shattered self; and reconstruction of self.33 |

| Duggleby (2000) | Nursing studies | Suffering is the basic social problem of pain.34 |

| Dysvik (2013) | Nursing studies | Suffering is a basic emotional experience and a response to illnesses that threaten one's physical or psychosocial integrity.35 |

| Edgar (2007) | Philosophy | [Suffering] is an experience of life never getting better, revealing in the sufferer only vulnerability, futility, and impotence.36 |

| Edwards (2003) | Medical ethics | [S]uffering is something felt. [and] must be distressing in some way for the subject. [and] of some significant duration. […]it must have a fairly central place in the mental life of the subject.37 |

| Fishman (1992) | Psychology | Suffering is a state of mind, an emotional experience that includes thoughts, meanings, and feelings that occur in response to many different causes. […] suffering is defined as a subjective perception of personal and physical disintegration.38 |

| Fordyce (1988) | Psychology | Suffering can be defined as an affective or emotional response in the central nervous system, triggered by nociception or other aversive events, such as loss of a loved one, fear, or threat.39 |

| Frank (2001) | Sociology | At the core of suffering is the sense that something is irreparably wrong with our lives, and wrong is the negation of what could have been right. Suffering resists definition because it is the reality of what is not.40 |

| Glas (2012) | Medical ethics | Suffering is, ultimately, an existential reality […] a way of relating to oneself, and by doing so, a way of relating to one's environment […] The suffering person expresses the inability to maintain a relationship toward the pain or toward other incapacities.43 |

| Gonzalez Baron (2006) | Psycho-oncology | […] the cause of suffering is the rupture of the balance between the evaluation of the threats and the resources to face it.44 |

| Gran (2008) | Nursing studies | [Suffering is] a personal threat to the core of being a whole person.46 |

| Grau (2009) | Medical ethics | Suffering is defined as a negative, complex emotional, and cognitive state, characterized by feeling under constant threat and powerless to confront it, having drained the physical and psychosocial resources that might have made resistance possible.47 |

| Kahn (1986) | Nursing studies | Suffering is defined as an individual's experience of threat to self and is a meaning given to events such as pain or loss.52 |

| Knotek and Knotkova (1998) | Psychology | We consider “suffering” as any unpleasant affective cognitive or affective evaluation of perceived, mentally presented, and processed information.54 |

| Krikorian (2012) | Palliative care | [Suffering is] a multidimensional and dynamic experience of severe stress that occurs when there is a significant threat to the whole person and regulatory processes are insufficient, leading to exhaustion.55 |

| Kugelman (2000) | Health psychology | […] suffering [is] the art of the cultural elaboration of performances of pain. In suffering, ‘I’ take a point of view on pain.56 |

| Lackner et al. (2005) | Psychology | If persistent, pain can compromise quality of life, heighten attentional focus to bodily sensations and other sources of internal experience (eg, worry), and tax adjustment […]. With these changes, psychological distress spreads to and damages other aspects of one's self-concept (e.g., self-evaluative concerns relating to one's self-identity, self- esteem, and role status, […]. These changes make up the long term suffering aspect of pain.57 |

| Lackner & Quigley (2005) | Psychology | […] suffering […] refers to the emotional experiences and long-term meaning the pain.58 |

| Meeker (2014) | Palliative care | Suffering [is] the physical, emotional, and spiritual distress that accompanies advanced life-limiting illness.61 |

| Monin (2009) | Gerontology | […] suffering [is] a holistic construct defined by three measurable dimensions: psychological distress, physical symptoms, and existential/spiritual distress.62 |

| Mount (2007) | Palliative medicine | […] the QOL continuum [is] a dialectic that extends from suffering and anguish at one extreme to an experience of integrity and wholeness at the other.64 |

| Murata (2006) | Palliative care | We defined “psycho-existential suffering” as “pain caused by the extinction of the being and the meaning of the self.65 |

| Norden-feldt (1995) | Medical ethics | Conversely, negative quality of life is of 2 kinds, the emotion of unhappiness and the sensation of pain […]. To denote both sets of cases, we may use the term “suffering”.67 |

| Pilkington (2008) | Nursing studies | […] suffering as an experience of health and quality of life in which one recognizes the possibility of nonbeing.72 |

| Priya (2012) | Sociology | […] suffering [is] overwhelming somatic pain or illness and its anticipation and other forms of severe distress arising in the sociomoral context.74 |

| Pullmann (2002) | Medical ethics | […] suffering [is] the product of [physical], psychosocial, economic, or other factors that frustrate an individual in the pursuit of significant life projects.75 |

| Rodgers (1997) | Nursing studies | Suffering is defined as an individualized, subjective, and complex experience that involves the assignment of an intensely negative meaning to an event or a perceived threat.79 |

| Roxberg (2014) | Theology | Suffering is the opposite of action […] because in action, one exercises one's freedom to acquire something that one desires. […] in suffering, one is the victim of a chain of events that threatens and is out of one's control […].81 |

| Streeck (2020) | Medical ethics | [Suffering is a] complex of physical, emotional, social, and spiritual elements […].84 |

| Strong (1999) | Sociology | The suffering associated with chronic pain can be understood as meanings and actions derived from forms of conversation in which the sufferer participates.85 |

| Svenaeus (2015) | Medical ethics | [Suffering] is found to be a potentially alienating mood overcoming the person and engaging her in a struggle to remain at home in the face of loss of meaning and purpose in life.87,88 |

| Svenaeus (2020) | Medical ethics | See Svenaeus (2015) |

| Tate & Pearlman (2019) | Medical ethics | Child suffering can be understood only as a set of absences—absences of conditions such as love, warmth, and freedom from pain.89,90 |

| Tate (2020) | Medical ethics | See Tate & Pearlman (2019) |

| van Hooft (1998) | Medical ethics | […] suffering is to be understood as the frustration of the tendency towards fulfilment of […] various aspects of our being.92 |

| Wade (1992) | Psychology | [Suffering] involves long-term cognitive or reflective processes that are related to the meanings and implications that pain holds for one's life in general.93,94 |

| Wade (2002) | Psychology | See Wade (1992) |

| Wilson (2007) | Palliative care | […] suffering is held to be a state of severe distress that is subjective and unique to the individual, arising from the perception of threat to one's integrity as a biologic, social, or psychological being.96 |

| Yager (2021) | Psychiatry | Suffering is the subjective experience of pervasive negative mood and psychic pain occupying most of one's mental space for a considerable length of time.98 |

The table lists all articles that explicitly offer a definition of pain-related suffering. For a full list of all articles from our text corpus including study characteristics, see Appendix H, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13.

For this, we used the key word summaries of the 60 definitions that we obtained manually with the method described above. If 2 or more key words from different definitions (1) were identical, (2) were based on the same lemma (eg, “body” and “bodily”), or (3) were clearly synonymous in the present context (eg, “bodily” and “physical”), they were given the same code. It was then counted how often each code was used. Only key words that were part of at least 2 definitions, ie, whose code was used at least twice, were kept, and compiled into a shortlist. Based on this list, we formulated an integrative definition of pain-related suffering.

Our aim was to arrive at a real not merely a nominal definition.49 We cannot cover the epistemological debates around this term, but we follow Gideon Rosen,80 who states that “to define a property F is to specify some condition Φ such that it lies in F's nature that whenever a thing is F, or Φ, the fact that it is F is grounded in the fact that it is Φ.” Furthermore, we aimed for our definition to be both representative of the literature and concise. Representativeness was ensured as we incorporated only those aspects of pain-related suffering that appeared in at least 2 definitions from our text corpus. In terms of concision, our objective was to include only essential terms from our shortlist, ie, to allow our definition to encompass all experiences identifiable as pain-related suffering, without incorporating superfluous descriptions. Terms from our shortlist, that were not integrated into the primary definition, informed supplementary expansions, mirroring the notes in the format of the IASP definition of pain.77

2.3.2. Research question 2: summarizing the literature into a multidimensional conceptual framework

To summarize the literature into a conceptual framework, we first used the procedure described above for summarizing the definitions. However, this time, we used the verbatim quotations and key words that were extracted for answering another conceptual question from our data extraction form (“What dimensions or types of suffering are differentiated?”). Eighty-two articles specified an answer to this question. As described above for the shared essential elements of the definitions, it was examined whether different key words referred to the same dimension of pain-related suffering, and the number of articles describing this dimension was counted. If a dimension was mentioned by at least 2 articles, it was included into the conceptual framework.

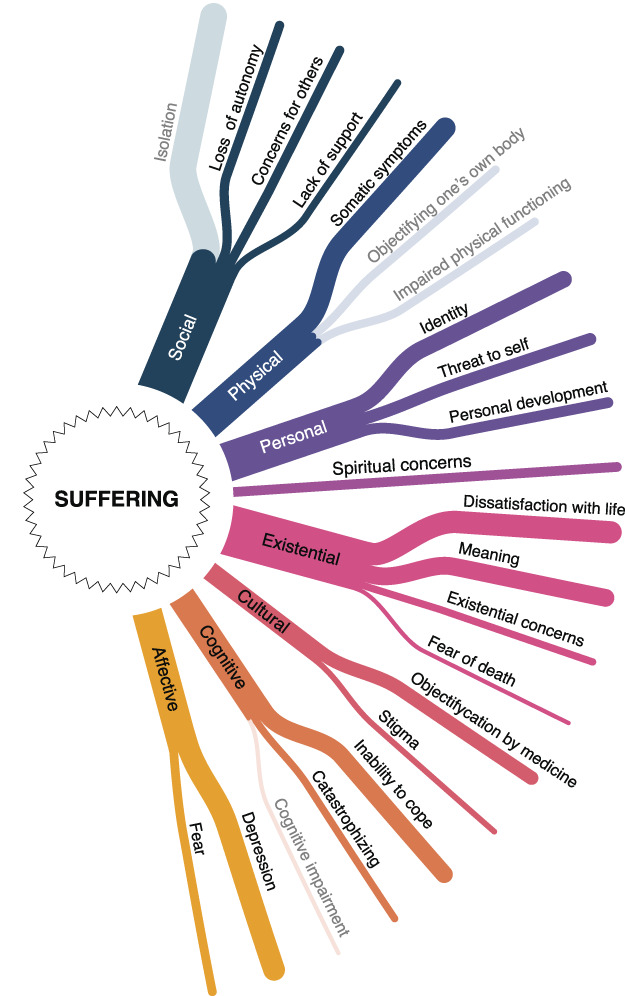

To anticipate, we identified 8 dimensions of pain-related suffering with this procedure. However, as can be seen in Figure 1, those dimensions are very broad and call for further differentiation. Therefore, in a next step, we applied the abovedescribed categorization procedure to the key words extracted for yet 2 other conceptual questions from our data extraction form. We analyzed which antecedents and consequences of suffering were mentioned repeatedly in the literature. Seventy-five articles provided an answer to at least 1 of these questions. This way, beyond the explicit mentioning of dimensions of pain-related suffering, additional information from the full texts could be used for our framework. The result was a list of 58 important aspects of pain-related suffering, although, in this case, not dimensions or defining elements but antecedents and consequences. These were allocated to the 8 dimensions identified in the first step and serve the purpose to further illustrate what these dimensions contain. This was based on theoretical considerations, but we avoided any controversial theoretical commitment. For instance, one of the 58 key word summaries of antecedents and consequences of suffering on the list was “catastrophizing,” which the articles in our text corpus described in terms of classical cognitive behavioral theory.29,58,95 Accordingly, it was allocated to the “cognitive” dimension.

Figure 1.

The multidimensional conceptual framework of pain-related suffering. The figure visualizes the conceptual framework of pain-related suffering. It distinguishes 8 dimensions of pain-related suffering, which are further specified by 2 to 4 descriptors—with the exception of the spiritual dimension. The strength of the lines that stand for the different dimensions and descriptors represents the number of conceptualizations from the literature that are summarized in each of them. The 4 descriptors “isolation,” “objectification one's own body,” “impaired physical functioning,” and “cognitive impairment” are not included in the final conceptual framework for pain-related suffering. For the purpose of clarity, they are nevertheless visually labeled (in a lighter color) to make the differences between the manually determined and the final framework transparent.

However, although the 58 key word summaries of antecedents and consequences of suffering give a systematic overview of conceptualizations in the literature and are helpful to specify the dimensions of pain-related suffering in detail, for the purpose of an accessible and ready-to-use framework for future scale construction, their level of detail is overly intricate. Therefore, in an additional step, we summarized them into 22 “descriptors”—2 to 4 for each dimension—that grant a quick understanding of the 8 dimensions and should be more helpful for elaborating future operationalizations of pain-related suffering. Appendix F, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13 shows which key words were summarized by which descriptor.

2.4. Step 3: cross-validation using machine learning

Because a qualitative approach, despite all efforts to be objective and systematic, is inevitably based to some extent on subjective judgements, we used the possibilities of machine learning through natural language processing (NLP) for cross-validation. For this purpose, we used artificial intelligence (AI)–based unsupervised learning techniques to process our text corpus.

2.4.1. Research question 1: how is pain-related suffering defined in current pain research?

To validate the integrative definition of pain-related suffering obtained with manual qualitative methods (Table 2), we conducted 2 analyses using large language models (LLM) to generate definitions of pain-related suffering. Both were based on the 111 articles from our text corpus.

Table 2.

Integrative definition of pain-related suffering.

| Definition |

| A severely negative, complex, and dynamic experience in response to a perceived threat to an individual's integrity as a self and identity as a person. |

| Expansions |

| Pain-related suffering is experienced to different degrees on a physical, spiritual, existential, personal, social, cultural, affective, and cognitive level. |

| Pain-related suffering is often associated with feelings of loss, lack of control, illness, alienation, and reduced quality of life. However, none of these can in itself be considered suffering, if it is not experienced as a threat as defined above. |

| Pain-related suffering is often a long-term experience but not necessarily so. |

| Pain and pain-related suffering are related but distinct phenomena. Either can cause or enhance the other. |

| The experience of pain-related suffering depends on the complexity of the affected individual. Newborns do suffer, but their suffering is not taking place on, eg, an existential or spiritual level, and they are not threatened as persons but rather as selves. |

The table shows our integrative definition of pain-related suffering based on the examined literature. The definition is amended by expansions that further describe the multidimensional character of pain-related suffering. Taken together, definition and expansions include all aspects of pain-related suffering that were used in the definitions of at least 2 articles from our text corpus.

The first LLM-based analysis applied GPT-3.5, which is based on the generative pretrained transformer (GPT) large language model,14 to generate a definition of pain-related suffering. For this purpose, we used the same 60 verbatim quotations whose key word summaries were used for the manual analysis described above.

However, it is possible that a synthesis of the manually extracted verbatim quotations with a large language model yields the same result as our manual synthesis, but both misrepresent the text corpus because the extraction of the verbatim quotations itself was flawed. Therefore, we also generated an integrative definition of pain-related suffering based on the full texts of the 111 articles from our text corpus. Conducting 2 different analyses with large language models allowed us to cross-validate the extraction and synthesis process separately: If the first LLM-definition differed from the manually obtained definition, this could indicate a mistake in the manual synthesis of the definitions; however, if the second LLM-definition differed from the manually obtained definition, this could indicate a mistake in the extraction of the quotations. We expect that both LLM-based definitions show a high similarity to our manually obtained definition.

In the second LLM-based analysis, we used the text-davinci-003 model (GPT-3).14 For each mentioning of the term “suffering” found in the full texts, we extracted 25 words before and after the term “suffering.” The range of ±25 words was chosen because this is approximately the length of 2 average sentences in scientific publications.45 This resulted in 8910 matching text strings each consisting of 51 words. The resulting 8910 strings were fed iteratively into GPT-3, asking it to define suffering from the new portion of string while taking into account the definition generated in the previous iteration. The exact instructions/prompts for both analyses are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Similarity metrics comparing our definition with those from GPT-3.5/GPT-3.

| Large language model used | Instructions/Prompts used in GPT-3.5/GPT-3 | Vector similarity | ROUGE-1 F1 score |

ROUGE-1 F1 score (nouns and adjectives) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-3.5 (Jan 30, 2023 release) | Based on the verbatim quotes loaded in 2 batches and summarized | 0.965 | 0.568 | 0.436 |

| GPT-3 text-davinci-003 (with settings: temperature=0, max_tokens=1500) |

Word window of 25 words around “suffering.” That is 8910 strings; 297 iterations were done with following prompts: Step 1: “Using these phrases: <First 30 strings> Create a one paragraph scientific definition of suffering. Suffering is” Steps 2-296: “Using this definition: suffering is <Definition from Step 1> And these phrases: <Next 30 strings> Create a one paragraph scientific definition of suffering. Suffering is” |

0.941 | 0.491 | 0.349 |

| BASELINE | [pain-related suffering is] the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person vs [pain-related suffering is] an unpleasant experience associated with negative cognitive, emotional, and autonomic response to a stimulus | 0.913 | 0.372 | 0.222 |

The table displays the similarity values obtained from comparing the definitions generated by GPT-3.5 and GPT-3 to the integrative definition obtained with conventional qualitative methods, as well as baseline similarity values for comparison in the bottom line. Vector similarity was calculated using embeddings from the text-embedding-ada-002 GPT-3 model.

To estimate how closely the resulting definitions from the 2 analyses with large language models matched our reference definition obtained manually, we used 3 commonly used paragraph proximity metrics: vector similarity, using embeddings from the text-embedding-ada-002 GPT-3 model; lexical similarity, using ROUGE-1 F1 score based on tokens; and a variation of ROUGE-1 F1 score using only lemmas of nouns and adjectives. All scores were normalized, taking only values between 0 and 1, where 1 indicates a perfect fit between 2 formulations. The results can be found in Table 3.

There are no general conventions or cutoff values for the interpretation of similarity metrics. However, an established means to guide interpretation is to juxtapose the comparison of interest to a baseline comparison. Therefore, we also calculated the same 3 paragraph proximity metrics to quantify the similarity between 2 prominent definitions from our text corpus that can be seen as paradigmatic for their respective fields,20,29 to guide interpretation. Note that these definitions share the goal to define pain-related suffering and refer to a partly overlapping literature base. Accordingly, a high similarity can be expected for this baseline. However, we expect that the similarity values for the comparison between our manual definition and the definitions provided by the large language models will be considerably closer to 1 because they not only try to define the same concept but also are based on the exact same text corpus.

2.4.2. Research question 2: summarizing the literature into a conceptual framework

To cross-validate the conceptual framework of pain-related suffering, we used topic modeling, an unsupervised machine learning approach for the automatic discovery of topics in large text corpora.11 The output of a topic model is lists of words, known as top word lists, that most likely are characteristic for the different topics within a text corpus. For a detailed description of the method in general, refer Bittermann.9 For our purposes, topic modeling offered the opportunity to discover aspects of pain-related suffering that are frequently discussed in our text corpus. These aspects of pain-related suffering detected by the AI were then compared with the 22 manually obtained descriptors from our conceptual framework for cross-validation.

We used the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) algorithm to generate topic models. For the implementation in R (Version 4.1.2.), we used the packages “quanteda,” “text2vec,” and “tidyverse.” In text preprocessing, stop words, special characters, numbers, and punctuation were removed from the corpus. We also tested the effect of both word stemming97 and the use of n-grams51 in a probatory model, but neither technique improved the interpretability of the data. We employed identical word windows to those used in the analysis conducted with the text-davinci-003 model mentioned earlier. It is worth noting that each word window was treated as an individual document by the algorithm. This approach allowed us to focus on specific sections of the articles rather than seeking topics across the articles as a whole.

Data cleaning was conducted by 2 researchers (J.T. and N.N.S.) based on the results of a “standard model,” which extracted 30 topics from the corpus using standard settings with α = 1.67, ε = 0.03, and λ = 0.4.48,82 In an iterative process, we removed not only undetected stop words but also terms that were expressive of the shared (academic) style of the examined articles but did not carry significant meaning for our research question, as well as proper names.

Because neither the number of topics K nor α, ε, or λ can be determined theoretically, 2 reviewers independently rated probatory extractions with varying settings and agreed to extract K = 30 topics, using standard values for α, ε, and λ.

To compare the results of topic modeling to the manually obtained descriptors from our conceptual framework, we developed a variation of what is called topic labeling. Usually, topics are given labels based on what is a shared element of most top words,73 this can be done by humans or automatically. Giving a straightforward example, if the top words are “chair,” “table,” and “couch,” an obvious choice for a topic label would be “furniture.” We changed this procedure slightly, insofar as we not only looked for a commonality between the top words but also determined which of the topics showed a clear similarity to 1 of the 22 descriptors of pain-related suffering identified by our manually obtained conceptual framework. Those descriptors of the framework that were not confirmed by the topic model will be excluded from the final conceptual framework of pain-related suffering.

Two researchers (J.T. and N.N.S.) conducted the comparison between the manual and the machine learning approach independently. The agreement rate between both researchers was 90%, ie, for 27 of the 30 identified topics, there was agreement about whether they corresponded to 1 of the manually obtained descriptors of the conceptual framework. Disagreements were resolved in direct discussion.

3. Results

3.1. Step 1: study characteristics

The initial database search identified 6179 articles. After the removal of duplicates, 3813 articles remained. Based on title and abstract screening, 3434 were excluded because they did not meet the selection criteria. Of the remaining 379 articles, only 271 could be retrieved and were examined in detail. In the full-text screening, another 160 articles were removed from the text corpus because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. In 118 cases, articles were excluded because they did not use the term “suffering” in a conceptual way, ie, did not provide an answer to at least 3 of the conceptual questions shown in Appendix E, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13. Twenty-two articles were excluded because pain was not sufficiently discussed in their notion of suffering. A complete report about all reasons for exclusion in the full-text screening can be seen in Appendix C, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13.

Appendix H, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13 shows the study characteristics. Of 111 articles from 26 different countries, 45 were theoretical studies in an essay format. Forty-seven articles were empirical studies, of which 23 used qualitative, 22 quantitative, and 2 mixed methods. The remaining 19 articles were reviews (11 narrative and 8 systematic).

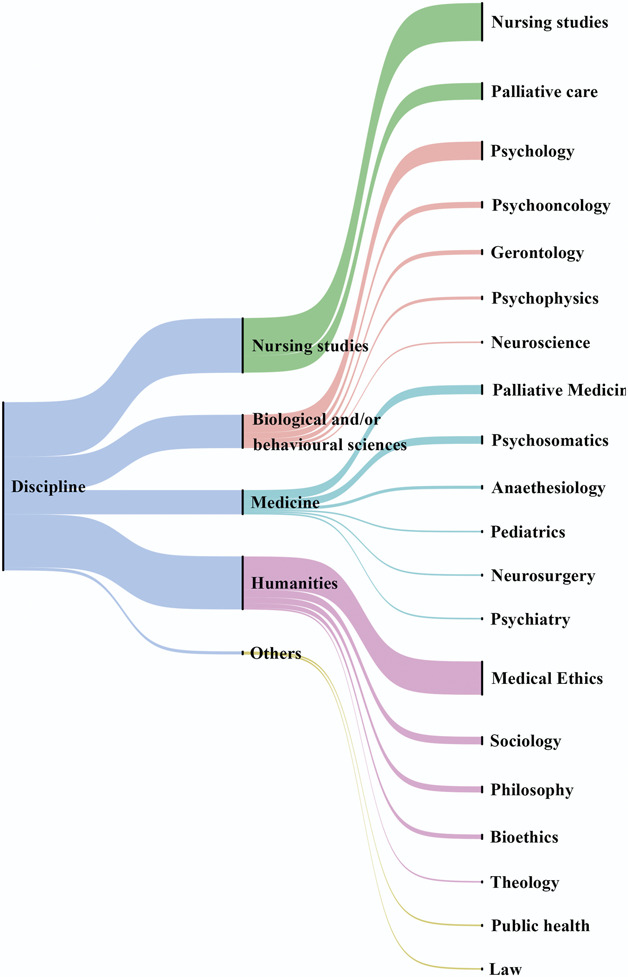

Thirty-six articles (32%) came from the field of nursing studies, in particular from the study of palliative care (11 articles; 10%). Thirty-five articles (32%) came from different disciplines within the humanities, in particular from the field of medical ethics (22 articles; 20%). Twenty-two articles (20%) came from behavioral and/or biological sciences, in particular from psychology (12 articles; 11%). Finally, 16 articles (14%) came from medical science, in particular from palliative medicine (6 articles; 5%). Figure 2 gives an overview of all disciplines present in the text corpus.

Figure 2.

The disciplines within the text corpus and their frequency. The diagram shows which disciplines the articles in the text corpus come from. In the middle, clusters of disciplines are listed, which are further differentiated by the list on the right. The width of each line indicates the number of studies from the respective discipline or cluster.

3.2. Step 2: data extraction and synthesis with (manual) qualitative research methods

3.2.1. Research question 1: how is pain-related suffering defined in current pain research?

All articles contributed to the conceptualization of pain-related suffering; however, only 60 offered an explicit definition (Table 1). Bringing together the essential aspects that were used to define pain-related suffering across these different articles, we propose an integrative definition of pain-related suffering as a severely negative, complex, and dynamic experience in response to a perceived threat to an individual's integrity as a self and identity as a person. The definition together with expansions that further describe the multidimensionality of suffering is shown in Table 2.

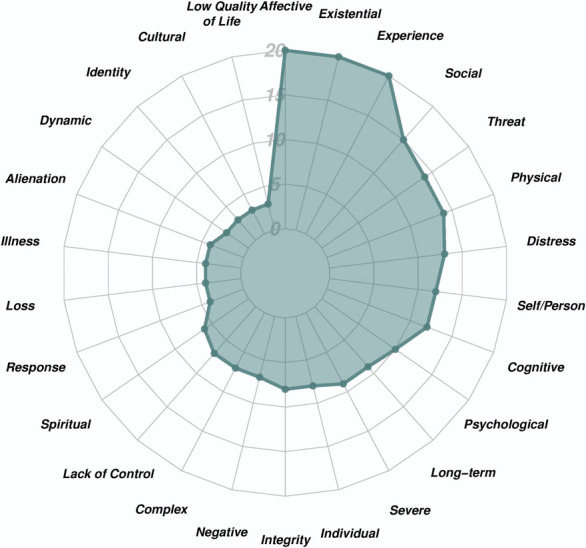

Each aspect of pain-related suffering that is part of at least one definition from our text corpus was included into our definition and its expansions. However, some aspects of pain-related suffering were mentioned by more definitions than others. Most frequently, the definitions from our text corpus referred to the affective and existential character of pain-related suffering. Figure 3 shows all aspects of pain-related suffering that were mentioned in the definitions in detail, as well as their frequency in the identified studies.

Figure 3.

Frequencies of the defining aspects of pain-related suffering in our text corpus. All aspects of pain-related suffering that were mentioned by at least 2 definitions from our text corpus are listed. The different circles of the diagram indicate how many articles mention each aspect.

3.2.2. Research question 2: summarizing the literature into a conceptual framework

Among the dimensions of pain-related suffering, the existential and the social aspect were most prominent in the literature. Thirty-seven articles (33%) mentioned experiences that could be summarized as existential, such as dissatisfaction with life or the feeling of having lost one's future. Thirty-six articles (32%) mentioned social experiences, such as isolation or the loss of (interpersonal) autonomy. Twenty-nine articles (26%) described experiences that were summarized as the personal dimension of pain-related suffering, such as the experience of a threat to the self. Twenty-seven articles (24%) pointed out the physical dimension of pain-related suffering, eg, by pointing out the importance of general somatic symptoms. Twenty-two articles (20%) referred to aspects that belong to the affective dimension of pain-related suffering, such as depression. Twenty articles (18%) described cognitive aspects of pain-related suffering, such as the perceived inability to cope with one's pain. The least frequently mentioned first-level dimensions of pain-related suffering were the cultural and the spiritual. Fourteen articles (13%) described experiences that could be summarized as cultural dimension of pain-related suffering, such as the experience of being objectified by medicine. Seven articles (6%) mentioned spiritual aspects as an important part of pain-related suffering.

For each of the 8 dimensions, our manual procedure identified 2 to 4 descriptors that further characterize the respective dimension. For instance, the social dimension of pain-related suffering was further described in our text corpus as being related to isolation, loss of autonomy, concern for others, and lack of support. An exception was the spiritual dimension which was not further specified in the literature. Figure 1 shows all dimensions that are part of our conceptual framework and their respective specifications.

As described above, the descriptors that specify the dimensions of suffering were obtained by summarizing the more fine-grained key word summaries taken directly from the literature. Overall, our manual approach identified 58 key words pertaining to the different dimensions of pain-related suffering (see Appendix F, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13).

3.3. Step 3: cross-validation using machine learning

3.3.1. Research question 1: how is pain-related suffering defined in current pain research?

Results indicate a very high semantic (vector) and a moderate lexical similarity between our manually obtained integrative definition of pain-related suffering and the definitions provided by the GPT 3.5 and GPT-3 large language models. The definition given by GPT 3.5 based on the verbatim quotations extracted by the authors had a vector similarity value of 0.965 and a ROUGE-1 value of 0.568 (0.436 for the variant using only lemmas of nouns and adjectives) compared with the integrative definition. The definition given by GPT-3 based on the full texts had a vector similarity value of 0.941 and a ROUGE-1 value of 0.491 (0.349 for the variant using only lemmas of nouns and adjectives) compared with the integrative definition.

The baseline comparison (between the 2 definitions from our text corpus20,29) resulted in a semantic (vector) similarity value of 0.913 and a lexical similarity of 0.372 (0.222 for the variant using only lemmas of nouns and adjectives). This confirms our expectation that the similarity between the definitions obtained by our different methods is descriptively higher than the similarity of a baseline comparison of similar text content.

Table 3 summarizes the results. The exact definitions provided by the large language models can be seen in Appendix G, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13.

3.3.2. Research question 2: summarizing the literature into a multidimensional conceptual framework

3.3.2.1. The topic model based on the Latent Dirichlet Allocation algorithm

As Table 4 shows, 25 of the 30 top word lists extracted by our search algorithm constitute clearly interpretable topics. In the other 5 cases, no distinct topic could be detected.

Table 4.

The topic model.

| Top Words | Topic label | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | take | art | mind | able | wisdom | actions | act | ability | malady | self-compassion | Personal Development/ Inability to Cope |

| T2 | family | individuals | dementia | caregivers | pw sds |

express | members | expression | past | suffered | Lack of Social Support |

| T3 | child | children | parents | outcome | claim | child's | copyright | perspective | opinion | baby | Children |

| T4 | person | subjective | specific | intactness | events | levinas | threaten | follows | matter | occurs | Threat to Self |

| T5 | pain | chronic | sensation | catastrophizing | caregivers | pwsds | express | affective | cognitive | fig | Catastrophizing |

| T6 | symptoms | infants | emotions | preterm | outcome | claim | child's | changes | perceptions | caregiver | |

| T7 | cancer | care | palliative | patients | intactness | events | levinas | hospice | last | msse | Existential Concerns/ Fear of Death |

| T8 | unbearable | present | overall | symptom | primary | patients | frequently | general | half | physicians | Somatic Symptoms |

| T9 | state | associated | feeling | given | consciousness | status | sense | light | well | beyond | Affective |

| T10 | medicine | nature | medical | new | goals | doctors | ferrell | primarily | coyle | bodies | Objectification by Medicine |

| T11 | spiritual | severe | distress | physical | mean | concern | ones | loved | percent | extreme | Concern for Others/ Spiritual Concern |

| T12 | illness | identified | Prism | hope | using | search | systematic | included | focused | losses | Research |

| T13 | human | moral | dignity | nurs | risk | stee ves |

severity | kahn | respond | disability | Stigma |

| T14 | nursing | practice | clinical | implications | management | adaptation | daily | sources | statements | attitudes | Nursing |

| T15 | patient's | relieve | goal | alleviate | dying | consequen ces |

lead | providers | euthanasia | patient | Euthanasia |

| T16 | feel | pediatric | injury | Kind | hospital | yet | cases | disorder | moreover | absence | Medicine |

| T17 | see | psychiatric | suffer | similarly | better | causes | describe | described | description | suffering | |

| T18 | healing | need | experiences | focus | attention | kleinman | victims | around | perspective | disaster | |

| T19 | self | emotional | loss | threat | others | negative | back | resources | identity | process | Loss of Identity |

| T20 | ill | noted | suffer | form | experi | chronically | course | response | logical | remains | |

| T21 | people | good | feelings | one | know | attitude | god | get | think | growth | Spiritual Concerns |

| T22 | one's | story | meaningful | change | experience | shared | culture | time | move | experiences | Loss of Meaning |

| T23 | caring | nurses | patient | ethics | nurse | phenomenological | phenomenology | professional | ethical | determined | Nursing |

| T24 | problem | lived | idea | paper | hooft | frustration | old | biological | role | hooft's | |

| T25 | life | related | quality | painrelated | third |

strug

gle |

little | plos | purpose | expe | Dissatisfaction with Life |

| T26 | health | suf | fering | support | subjects | women | group | age | social | perceived | Lack of Social Support |

| T27 | unpleasantness | pain | behavior | high | depression | stimulation | anxiety | national | higher | vas |

Depression/

Anxiety |

| T28 | bodily | low | object | like | decision | never | end | though | true | decisions |

Objectification

by Medicine |

| T29 | body | meaning | find | language | frankl |

mean

ings |

relationships | narratives | world | challenge | Loss of Meaning |

| T30 | existential | control | important | effects | autonomy | ex | phenomenon | situation | interpersonal | holistic |

Loss of Autonomy/

Existential Concern |

Each row shows the 10 top words found by the search algorithm for each topic, and—in the last column—the label(s) given to these top words. The respective top words that were considered indicative of the given label are written in bold and italics, and, in addition, underlined, in those cases where 2 interpretations seemed possible.

Among the 25 top word lists with clearly interpretable topics, in 4 cases, both researchers agreed that 2 interpretations are equally viable, ie, that the respective top word could be interpreted as either of 2 topics. This concerns the top word lists T1 (personal development/inability to cope), T7 (existential concerns/fear of death), T11 (concern for other/spiritual concern), and T30 (loss of autonomy/existential concern). Therefore, in Table 4, in those top word lists, the terms that indicate the second theme are underlined, and, in the last column, a second label is given.

3.3.2.2. Revisiting the manually obtained conceptual framework

The topic model in Table 4 shows that of the 25 clearly interpretable topics, 20 corresponded to 1 of the 22 descriptors of the manually obtained conceptual framework and were labelled accordingly. However, because in 2 cases, 2 topics corresponded to the same manually obtained descriptors, overall, 18 of the 22 descriptors of the manually obtained conceptual framework were confirmed by the topic model. Thus, we can state an agreement of 82% between the descriptors of the manually obtained conceptual framework and the topics from topic model.

Descriptors that were not confirmed by the machine learning approach were excluded (see the greyed out “branches” in Fig. 1). These descriptors included “impaired physical functioning,” “objectification of one’s own body,” “isolation,” and “cognitive impairment,” which are not included in our final conceptual framework for pain-related suffering.

4. Discussion

The overall aim of this study was to explore how pain-related suffering is defined in the existing literature and to develop a comprehensive conceptual framework that delineates its multifaceted dimensions. Our integrative definition posits pain-related suffering as a severely negative, complex, and dynamic experience in response to a perceived threat to an individual's integrity as a self and identity as a person. Our final conceptual framework for pain-related suffering identifies 8 discrete dimensions: social, physical, personal, spiritual, existential, cultural, cognitive, and affective. This framework can be directly used for scale construction and at the very least serve as a point of orientation for evaluating future and existing operationalizations. Instead of adding yet another theory of suffering, we offer a definition that brings together insights from different disciplines and can serve as a consensus definition against which new theories and operationalizations can be evaluated.

4.1. Integrating “self” and “person” in the definition of pain-related suffering

The most widely discussed definition of suffering as “the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person,” put forward by Eric Cassell, 20 has been criticized on various grounds.37,92 In particular, Bueno-Gómez17 pointed out that Cassell leaves open what exactly a person is and what it means that personal intactness is threatened, whereas Tate89 has argued that defining suffering in terms of personhood wrongly excludes beings as potential sufferers, which might not be considered as persons, such as preverbal children. In accordance with our systematic procedure, our definition includes the description of pain-related suffering as resulting from a threat to personal intactness because it is representative of huge parts of the literature.

The term “person” is used in this context, as in many definitions,22,38,46,87 to delineate pain-related suffering from other pain-related experiences. These other experiences may include “normal” pain-related discomfort or mild limitations in functioning, which individuals find aversive but perceive as tolerable. We argue that this does not require a complete theory of personhood. Suffering is distress in response to a threat to the person, insofar as it does not affect a specific goal or an isolated area of life.20,52,55,92 It deeply affects the individual at their core to an extent where they cannot continue to be who they are, if the distress persists.21 “Person” can be used in definitions of suffering in this sense to refer to this fundamental relevance and intolerability of a particular distressing experience.

We argue that the intolerability of pain-related suffering, which in our definition is expressed by the term “threat to the integrity of the person,” is also what is behind prominent alternatives that are formulated in strong opposition to the (cassellian) conceptualization of pain-related suffering in terms of personhood.37,89,92 For instance, Stan van Hooft92 describes suffering as the “the frustration of the tendency towards fulfilment of […] various areas of our being.” Arguing philosophically from a teleological (Aristotelian) framework, he suggests that strong pain makes it impossible for the sufferer to realize his or her potential or purpose, or in other words to be what he or she is or should be. There are many conceptual differences between the various accounts summarized in our definition that we cannot cover here. However, the example of Cassell and van Hooft illustrates that even the most contrary approaches to pain-related suffering describe it as (threatening to) transform the sufferer into something different from themselves, which is intolerable for the sufferer. We suggest that this intolerability lies at the core of pain-related suffering.

Our definition describes pain-related suffering as distress in response to “[…] a threat to an individual's integrity as a self or identity as a person.” “Integrity as a self” refers to the fundamental and basic awareness or sense of existence that an organism might have.26,41 By contrast, “identity as a person” focuses on more elaborate social, cultural, and relational spheres, representing how one sees oneself in relation to the external world, including societal interactions and perceptions.68 We suggest that these aspects, although closely interwoven, influence pain-related suffering in distinct manners. Our definition applies to any organism that can be said to possess a sense of self, which arguably includes preverbal children,26,78 whether or not they can be categorized as persons at their current stage of development. At the same time, unlike definitions that dispense of the term person completely,21,65 our definition also recognizes that “person” captures the intolerable character of pain-related suffering and has also been established as an umbrella term to describe essential aspects of (adult) suffering, namely, a high level of complexity, reduced quality of life,67 fear of the future,42,73 loss of meaning,9,28,65 and a breach of one's personal narrative.30,40,71 This does not apply to preverbal children and would not fully be captured by using only the term “self” in a definition of suffering. We suggest that as for the term “person,” one does not need a complete theory of selfhood, to define suffering as distress involving a threat to the self, and we argue that the differences between “person” and “self” we just sketched justify the usage of both terms in our integrative definition of pain-related suffering.

4.2. Applying our definition beyond the context of pain

In our study, we primarily focused on the conceptualization of suffering within the context of pain, delving into the existing literature on physical pain. It is crucial to acknowledge that our research scope intentionally excluded other domains of suffering in patients with severe diseases, although it is reasonable to anticipate that similar definitional frameworks may apply to diverse forms of suffering. The generalizability and adaptability of our definition encourages contemplation of its application in varied clinical scenarios, including domains like cancer, amputation, or dementia.6,10,27,99

We hypothesize that although there may be substantial commonalities between the dimensions of suffering associated with pain and the dimensions of suffering associated with conditions like cancer or dementia, there could be notable distinctions. For instance, in the case of suffering related to dementia, suffering might primarily encompass aspects related to self, identity, and loss.83 Nonetheless, these hypotheses remain in the realm of speculation. To achieve a thorough comprehension of the individual's experience with disease, it is imperative to demarcate the various dimensions and disease states within the scientific discourse on suffering. The quantification of diverse facets of suffering, stratified by precise medical conditions, can facilitate the development of tailored interventions targeting specific symptoms or conditions. Our study aims to serve as a methodological prototype, encouraging subsequent research to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of suffering across a spectrum of pain disorders and related clinical contexts.

4.3. Discerning the interplay and bidirectional dynamics of suffering and pain

The concept of pain-related suffering is not restricted only to suffering that is caused by pain. Suffering caused by pain can in turn worsen and elongate pain,9,19 and even in the initial absence of pain, (psychological) suffering can give rise to physical pain in the first place, which can be conceptualized as somatization.25 However, an exploratory analysis of the extracted data showed that the influence of suffering on pain has received far less attention. Eighteen articles explicitly discuss the causal relationship between pain and suffering, all of which mention pain as a cause of suffering, whereas only 4 articles also mention the opposite direction of causation. We suggest that future research should more explicitly address the bidirectional character of the relationship.

Our definition of pain-related suffering as an experience in response to a perceived threat to an individual's integrity as a self and identity as a person resembles some definitions of pain itself. In particular, Cohen et al23 defined pain as “an apprehension of threat to […] bodily or existential integrity.” We argue that such definitions of pain, although expressing valuable insights, stretch the term “pain” too much. Pain does not necessarily involve any apprehension of a threat to integrity, be it bodily or existential (eg, even a heat stimulus judged by the individual to be “perfectly safe” may well be judged painful). Pain is closely entangled with, but experientially distinct from, such apprehension processes, which, we argue, should be called pain-related suffering. In other words, the sensation of pain is intrinsically unpleasant, and this unpleasantness involves basic emotions. However, the more complex emotions, which can in turn enhance this unpleasant sensory and (basic) emotional experience, are not part of the pain sensation itself but of pain-related suffering. We suggest that the insights expressed in definitions like the one from Cohen and colleagues are best placed by further elaborating the concept of pain-related suffering, which brings into focus the full complexity of pain, without widening the concept of pain too much and thereby leaving the consensus reached in the IASP definition of pain.77

4.4. The conceptual framework and the threshold of suffering

Pain-related suffering—like pain itself76—is a subjective experience that differs between individuals,79,96,98 which is of importance for interpreting our multidimensional conceptual framework. We suggest distinguishing carefully between an objective and often external threat (stressor) and the subjective reaction to it (distress). Our conceptual framework refers to the latter. Its dimensions are (clusters of) subjective reactions to threats and can be called suffering, if and only if they affect the individual in whom they arise, ie, if they threaten the sufferer's identity as a person or integrity as a self. For example, one descriptor is called “lack of support.” Objectively, a person may receive no social support at all for their pain. Some individuals describe this as a feeling of fundamental separation from other people that affects their whole being.31,46,64 Others may find it distressing without being deeply affected by it. Variability in personal resources21,47,55 and the uniqueness of life narratives53 are often referred to as explanations for the subjective and individually different character of pain-related suffering.

4.5. The significance of the existential and social dimension

It has been stressed repeatedly that suffering is a wholistic experience influencing all aspects of the affected person's life.20,52,55,92 Nevertheless, our framework shows that the existential and the social dimension are of particular importance. Thirty-seven articles discussed the existential dimension of pain-related suffering. The important role of this aspect may be related to the fact that many articles discussed pain in the context of life-threatening illness (15 articles focused exclusively on cancer pain). Baines and Norlander4 even suggest using the terms “existential distress” and “existential pain” as synonyms for suffering. Thirty-six articles discussed the social dimension of pain-related suffering. Recently, Sullivan et al.86 have argued that social factors should be seen not only “as modifiers of biological causes […] but as equal contributors to pain” (p. 1). In accordance with this, our conceptual framework represents the importance of the social and the existential dimension but at the same time does justice to the wholistic character of suffering by bringing the various dimensions of suffering together into one framework.

4.6. Evaluation and application of the conceptual framework

We suggest that our framework can assist operationalization in different ways. (1) Initially, it can help to determine, whether, in a particular research context, pain-related suffering should be measured with all its dimensions or whether a focus on specific dimensions is more appropriate. Although research suggests a close relationship between the different dimensions, the development of a more nuanced terminology will help to avoid equivocation between them. For instance, it is possible that in cancer research, there is a particular interest in existential pain-related suffering, whereas in psychotherapy research, affective or cognitive pain-related suffering are of greater relevance. Conclusions about one type of suffering may not apply to another, and our framework can help to adjust the measurement of pain-related suffering to the respective need. (2) Subsequently, the descriptors of the conceptual framework give a general orientation, what each dimension involves according to the literature, and (3) for more detailed guidance in scale construction, the key words, that the framework is based on, can be consulted. There are existing measures from related contexts that can be used to quantify the concepts we extracted from the literature. For instance, the key word “exhaustion” could be measured using a subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory,59 and “unfinished business” could be measured using the Unfinished Business Questionnaire.60 Similarly, a straightforward operationalization should be feasible for most of the key words that the descriptors are based on. This way, our conceptual framework, together with its extension can be helpful for different stages of the operationalization process.

More research is needed to examine whether the structure of our conceptual framework could be interpreted as the factor structure of pain-related suffering. Conceptualizations of pain-related suffering were extracted systematically from the examined literature and then summarized based partly on theoretical considerations. Although we cross-validated the descriptors by analyzing our text corpus with an unsupervised language model, and the detected topics mirrored the identified descriptors very closely, it needs to be examined empirically whether the descriptors/topics can be interpreted as a factor structure. Nevertheless, our conceptual framework may serve as a point of orientation for future research towards that end.

4.7. Methodological considerations

Comparing the manually obtained integrative definition with the definitions provided by GPT-3.5 and GPT-3 large language models based on the same textual basis, we found a very high semantic similarity (with a vector similarity metric of 0.963 and 0.941, respectively) and a relatively low lexical similarity (ROUGE-1 metrics between 0.328 and 0.474). That the analysis based on the GPT-3.5 large language model yielded a higher similarity value than the one based on GPT-3.0 can be explained by the fact that it was based on the same quotations as the manual analysis, whereas the analysis based on GPT-3.0 was based on the full texts. However, both similarity values are very high, and higher than baseline (0.913), indicating that both manual data extraction and manual data synthesis were reliable. The fact that in absolute terms, the values are not much higher than baseline, can be explained by all values already being close to 1. The difference between the semantic and lexical similarity measures could be explained by the fact that although we used a standardized procedure, theoretical knowledge influenced the exact choice of terms for the integrative definition. For instance, in the manually obtained integrative definition, we chose the term “affective” over the term “emotional” because it is the more general concept in psychological research.66 The fact that such semantic details may still be missed by large language models also illustrates the strength of combining manual and machine learning based methods in concept development. Our combined approach allows to pay attention to conceptual detail while at the same time avoiding the risk of subjective judgment as much as possible.

Our multidimensional conceptual framework of pain-related suffering was derived from the literature, based on manual extraction and summarization. Although the 8 dimensions were taken directly from the literature, the 18 descriptors are based on a summary of conceptualizations from the literature and hence involve theoretical considerations. Therefore, they were cross-validated using topic modeling with the LDA algorithm.11 The congruence (82%) between the descriptors and the topics found by the algorithm shows that topic modeling can be a useful tool for theory development in pain research. Especially for reviewing conceptual research, this can significantly reduce subjectivity. At the same time, we found that the topic model also identifies topics unrelated to the concept of interest. This cannot be prevented completely because—although pain-related suffering was the shared theme of all articles in the text corpus—it is likely that there are topics shared by a subgroup of articles that are unrelated to suffering but are nevertheless detected by the algorithm. Accordingly, we suggest that the cross-validation of conventional qualitative methods and machine learning is a promising account for systematically reviewing conceptual data.

4.8. Limitations

There are some limitations of our study that need to be considered. Our search strategy was to look for articles that used the terms “pain” and “suffering” in title or abstract, as well as at least 1 of 8 terms indicating that the article had in part a theoretical focus (see Appendix A, http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13). On the one hand, the list of terms we used is not conclusive, and it is possible that there are other terms with which we could have detected additional articles. On the other hand, it is possible that there are articles that did not use any of the abovedescribed terms, for instance, articles with a strong empirical focus using a minimal but still relevant amount of theory. However, it can be expected that our cross-reference search would have detected any overlooked conceptualizations, even in purely empirical articles. Regarding the search terms itself, it can be said that in probatory searches, no additional term resulted in a surplus of eligible articles.

Another primary limitation is a risk of bias because only one researcher conducted the extraction of verbatim quotations from the text corpus. Possibly, the perspective of the review was narrowed by this, insofar as the quotations may have been selected based on a subjective predefined notion of suffering stemming from specific articles or authors. However, at least for the extraction of definitions, it can be argued that their identification within an article is a very unambiguous task, insofar as definitions are usually emphatically expressed in sentences such as “suffering is…,” or “suffering can be seen as.” Furthermore, the fact that we successfully cross-validated all our results, ie, both our exploration of the dimensions and of the definitions of pain-related suffering yielded very similar results across the different methods we used (machine learning and conventional qualitative methods), suggests that the bias in selecting relevant quotations was minimal.

We have used only academic articles as our data base. Although this is a viable approach, additional data sources need to be consulted to address this important issue. In particular, the perspective of patient stakeholders on their experience of pain and suffering is of high relevance. However, we argue that the present article is a first step in that direction, and we are currently designing an online survey using our conceptual framework as a guideline to collect and analyze responses (natural language data) from pain patients by asking them open questions about their suffering (for a similar current project see https://painstory.science).

5. Conclusion

There is currently no consensus on a definition of pain-related suffering. Important aspects and dimensions of suffering that are stressed in some parts of the literature are ignored in others. Our integrative definition brings all important contributions together and does justice to the multifaceted character of the experience of pain-related suffering. Furthermore, our conceptual framework indicates concretely, on which dimensions suffering is experienced and lays the ground not only for an operationalization of pain-related suffering as a whole but also for operationalizing specific aspects of pain-related suffering depending on the context.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendix A. Supplemental digital content

Supplemental digital content associated with this article can be found online at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/C13.

Supplemental video content

A video abstract associated with this article can be found on the PAIN website.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers, whose outstanding and constructive comments have made a substantial contribution to the enhancement of this manuscript and its current state. The submitted manuscript does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s). This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 1158 and by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung; PerPAIN consortium, FKZ:01 EC1904A). No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party directly or indirectly related to the subject of this manuscript.

Author contributions: Conceived and designed the study: N.N.S., J.T. and P.G.; analyzed the data: N.N.S., J.T., D.S., and A.Z.; wrote the paper: N.N.S., J.T. and D.S.; critically revised the manuscript: N.N.S., J.T., D.S., P.G. and T.W. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.painjournalonline.com).

N. Noe-Steinmüller, D. Scherbakov contributed equally to this manuscript.

P. Goldstein, J. Tesarz contributed equally to this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Niklas Noe-Steinmüller, Email: noe-steinmueller@posteo.de.

Dmitry Scherbakov, Email: scherbakov.dmitri@gmail.com.

Alexandra Zhuravlyova, Email: alexa.zhuravl@gmail.com.

Tor D. Wager, Email: Tor.D.Wager@dartmouth.edu.

Pavel Goldstein, Email: pavelg@stat.haifa.ac.il.

References

- [1].Adunsky A, Zvi Aminoff B, Arad M, Bercovitch M. Mini-suffering state examination: suffering and survival of end-of-life cancer patients in a hospice setting. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2008;24:493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aguilera B. Nonconscious pain, suffering, and moral status. Neuroethics 2020;13:337–45. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Andaya E, Campo-Engelstein L. Conceptualizing pain and personhood in the periviable period: perspectives from reproductive health and neonatal intensive care unit clinicians. Soc Sci Med 2021;269:113558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Baines BK, Norlander L. The relationship of pain and suffering in a hospice population. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2000;17:319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bellieni C. Pain definitions revised: newborns not only feel pain, they also suffer. Ethics Med 2005;21:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Belon HP, Vigoda DF. Emotional adaptation to limb loss. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2014;25:53–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bernier Carney K, Starkweather A, Lucas R, Ersig AL, Guite JW, Young E. Deconstructing pain disability through concept analysis. Pain Manag Nurs 2019;20:482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Best M, Aldridge L, Butow P, Olver I, Price M, Webster F. Assessment of spiritual suffering in the cancer context: a systematic literature review spiritual suffering in the cancer context. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1335–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Best M, Aldridge L, Butow P, Olver I, Webster F. Conceptual analysis of suffering in cancer: a systematic review. Psycho Oncol 2015;24:977–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Björkman B, Lund I, Arnér S, Hydén LC. The meaning and consequences of amputation and mastectomy from the perspective of pain and suffering. Scand J Pain 2017;14:100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI. Latent dirichlet allocation. J Machine Learn Res 2003;3:993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Boisaubin EV. The assessment and treatment of pain in the emergency room. Clin J Pain 1989;5(suppl 2):S19–25; discussion S24-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Broggi G. Pain and psycho-affective disorders. Neurosurgery 2008;62:901–20; discussion 919–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]