Abstract

PURPOSE

Female Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) survivors treated with chest radiotherapy (RT) at a young age have a strongly increased risk of breast cancer (BC). Studies in childhood cancer survivors have shown that doxorubicin exposure may also increase BC risk. Although doxorubicin is the cornerstone of HL chemotherapy, the association between doxorubicin and BC risk has not been examined in HL survivors treated at adult ages.

METHODS

We assessed BC risk in a cohort of 1,964 female 5-year HL survivors, treated at age 15-50 years in 20 Dutch hospitals between 1975 and 2008. We calculated standardized incidence ratios, absolute excess risks, and cumulative incidences. Doxorubicin exposure was analyzed using multivariable Cox regression analyses.

RESULTS

After a median follow-up of 21.6 years (IQR, 15.8-27.1 years), 252 women had developed invasive BC or ductal carcinoma in situ. The 30-year cumulative incidence was 20.8% (95% CI, 18.2 to 23.4). Survivors treated with a cumulative doxorubicin dose of >200 mg/m2 had a 1.5-fold increased BC risk (95% CI, 1.08 to 2.1), compared with survivors not treated with doxorubicin. BC risk increased 1.18-fold (95% CI, 1.05 to 1.32) per additional 100 mg/m2 doxorubicin (Ptrend = .004). The risk increase associated with doxorubicin (yes v no) was not modified by age at first treatment (hazard ratio [HR]age <21 years, 1.5 [95% CI, 0.9 to 2.6]; HRage ≥21 years, 1.3 [95% CI, 0.9 to 1.9) or chest RT (HRwithout mantle/axillary field RT, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.06 to 3.3]; HRwith mantle/axillary field RT, 1.2 [95% CI, 0.8 to 1.8]).

CONCLUSION

This study shows that treatment with doxorubicin is associated with increased BC risk in both adolescent and adult HL survivors. Our results have implications for BC surveillance guidelines for HL survivors and treatment strategies for patients with newly diagnosed HL.

BACKGROUND

Female Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) survivors treated with chest radiotherapy (RT) at a young age have a strongly increased risk of subsequent breast cancer (BC).1,2 Previous studies have shown that BC risk is higher after treatment at a younger age, with higher radiation doses and/or larger radiation volumes. Among women exposed to chest RT at age younger than 21 years, reported risks are comparable with those observed in BRCA mutations carriers.2-7 Several studies in HL survivors or childhood cancer survivors (CCS) reported a lower risk of radiation-associated BC among women who also received gonadotoxic treatments with high doses of alkylating agents (ie, procarbazine), or pelvic RT, compared with those who did not receive such treatments.8-10 This reduction of radiation-associated BC risk after gonadotoxic treatment has been attributed to a protective effect of early menopause. To decrease HL treatment-related gonadotoxicity, doses of alkylating chemotherapeutic agents and the use of pelvic RT have been reduced since the 1980s, while anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin, have become the cornerstone of chemotherapy for HL.11-13 Simultaneously, the volumes and doses used for chest RT have decreased.14-16 However, a previous study from our group among 5-year HL survivors treated between 1965 and 2000 did not demonstrate a lower BC risk in more recently treated patients.17

CONTEXT

Key Objective

To evaluate whether doxorubicin exposure is associated with breast cancer (BC) risk in female 5-year Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) survivors treated at age 15-50 years, between 1975 and 2008.

Knowledge Generated

Almost one in five survivors developed BC after 30 years of follow-up. Exposure to a cumulative doxorubicin dose of >200 mg/m2 was associated with a 1.5-fold increased BC risk, independent of age at HL treatment, receipt of chest radiotherapy (RT), or gonadotoxic therapy. Despite lower doses and smaller volumes of RT in contemporary treatment regimens, BC risk has not decreased in survivors treated between 1998 and 2008 compared with survivors treated between 1975 and 1986 (20-year cumulative BC incidence 7.8% v 8.2%, respectively).

Relevance (J.W. Friedberg)

-

These results emphasize the importance of very long follow-up for survivors of HL, and, if validated in other datasets, provide another factor to consider when evaluating risks of therapy. Ongoing trials incorporating checkpoint blockade and decreasing chemotherapy exposure have particular relevance given these findings.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Editor-in-Chief Jonathan W. Friedberg, MD.

Several studies in CCS populations reported increased BC risk after exposure to doxorubicin with and without chest RT,18-22 with data suggestive of dose-dependent increase in BC risk.

To the best of our knowledge, the association between doxorubicin exposure and BC risk has not yet been examined in HL survivors treated at adult ages. If doxorubicin exposure at adult ages were associated with BC risk, this could have implications for follow-up care of HL survivors, as well as for treatment strategies for newly diagnosed patients. Therefore, we assessed the effect of doxorubicin exposure on BC risk using a large cohort of female 5-year HL survivors, treated between 1975 and 2008, with a broad age range at the start of treatment.

METHODS

Study Population and Data Collection

This multicenter study cohort comprised 1,964 female 5-year survivors who had HL as their first malignancy and were treated in 20 Dutch centers (eight university medical centers, nine general hospitals, and three RT centers) in the Netherlands at age 15-50 years, between 1975 (when doxorubicin was introduced in HL treatment) and 2008.

Detailed information regarding HL diagnosis, and primary and relapse treatment(s) (radiation fields, chemotherapy regimens, and number of cycles) was collected from medical records as described previously.23-25 Cumulative doxorubicin and procarbazine doses were estimated on the basis of the number of cycles of prescribed chemotherapy regimens using standard dosages for each regimen.

For follow-up years until 1989, information on subsequent primary malignancies was collected directly from medical records and from questionnaires sent to general practitioners (questionnaire response until 1989: 96%).26 For follow-up from 1989 onward, information on subsequent BC was obtained through record linkage with the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), which has nationwide coverage since that year.27,28

Vital status and date of death were obtained through linkage with the NCR and through record linkage with the Central Bureau for Genealogy. For survivors treated from 1989 onward, the most recent linkage with NCR was complete until January 1, 2022. For survivors treated between 1975 and 1988, the last NCR linkage was performed in 2012, as current European privacy regulations complicate new linkages for these survivors.

Statistical Analysis

As only 5-year survivors were included in this study, time at risk started 5 years after start of HL treatment and ended at the date of diagnosis of invasive BC or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), date of death, or the censoring date (on the basis of completeness of NCR data, or date of last medical information), whichever occurred first. If not otherwise stated, BC encompasses both invasive BC and DCIS. BC diagnoses within 5 years after HL treatment (n = 2) were ignored, but these survivors did contribute person-time to our analyses from 5 years after HL treatment onward, as they were still at risk to develop contralateral BC. Any subsequent cancer after HL other than BC was ignored in all analyses. Calculation of expected BC numbers was based on age- and calendar year–specific BC incidence rates in the female Dutch population (derived from the NCR), multiplied by the corresponding number of person-years at risk observed in our cohort. From the observed and expected numbers of BCs, standardized incidence ratios (SIRs), absolute excess risks (AERs, per 10,000 person-years), and their corresponding 95% CIs were computed using standard methods.29

Cumulative BC incidence was estimated with death as a competing risk. Cumulative BC incidences according to period of HL treatment (1975-1986, 1987-1997, and 1998-2008) were compared using competing hazards regression models.30

In all multivariable analyses, the cumulative doxorubicin dose was included either continuously or as a categorical variable (either as doxorubicin yes/no, or categorized as: no doxorubicin, 1-200 mg/m2, and >200 mg/m2; Data Supplement, Table S1, online only).

Cumulative procarbazine dose was categorized as ≤4.2 g/m2, 4.3 to 8.4 g/m2, or >8.4 g/m2. RT to the chest was categorized according to the volume of breast tissue within the radiation field as follows: no chest RT (may include neck, supraclavicular, and/or infraclavicular fields), mediastinal field (not including axilla), mantle field or RT including axillary field(s) (MF/axillary RT), and unspecified RT fields. For analysis of effect modification, gonadotoxic treatment was defined as having received pelvic RT and/or a procarbazine dose >4.2 g/m2. Of all survivors treated with anthracyclines, 170 (13.3%) had received epirubicin. The association between epirubicin and BC risk was evaluated using receipt of epirubicin as a binary variable (yes/no), as 89% of epirubicin-treated survivors received a cumulative dose ≥420 mg/m2.

To identify treatment factors associated with BC risk, we used multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression, with attained age as the time scale. The proportional hazard assumption was assessed using graphical and residual-based methods. Age at HL diagnosis violated the proportionality assumption and analyses were therefore stratified for age at HL treatment as a continuous variable.

Interactions between doxorubicin and age at HL diagnosis, gonadotoxic treatment, MF/axillary RT, and time since HL treatment were evaluated by comparing models with and without a cross-product. For assessment of effect modification by time since treatment, a cross-product between doxorubicin and various cutpoints for time since treatment (either 15, 20, 25, or 30 years after treatment) was added to the model; models were compared using the Akaike's information criterion.

We performed several sensitivity analyses: (1) excluding DCIS; (2) excluding all survivors with missing data on treatment variables (complete case analysis); (3) reclassifying survivors treated with lung RT to the MF/axillary RT category; and (4) excluding survivors treated before 1989 to see whether our results were consistent when restricted to a more recent treatment era and NCR-reported BCs.

All reported P values are two-sided; P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with Stata statistical software, version 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The median age at first HL treatment was 27.8 years (IQR, 21.9-35.2; Table 1). Most HL survivors (69.8%) were treated with a combination of RT and chemotherapy; 11.4% received chemotherapy only. A total of 1,113 survivors received doxorubicin. Among the survivors who received chemotherapy, the proportion of survivors treated with doxorubicin increased from 32.6% between 1975 and 1986 to 84.5% between 1998 and 2008 (Data Supplement, Table S2). RT involving MF or including axillary field(s) decreased from 80.3% between 1975 and 1986 to 17.3% between 1998 and 2008. Receipt of gonadotoxic treatment decreased from 51.4% between 1975 and 1986 to 6.8% between 1998 and 2008.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Female 5-Year Hodgkin Lymphoma Survivors

| Survivor Characteristic | Total (N = 1,964), No. (%) | BC Eventa (n = 252), No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at first HL treatment, years | ||

| <21 | 416 (21.2) | 76 (30.2) |

| 21-30 | 730 (37.2) | 106 (42.1) |

| >30 | 818 (41.7) | 70 (27.8) |

| Period of HL treatment | ||

| 1975-1986 | 539 (27.4) | 101 (40.1) |

| 1987-1997 | 677 (34.5) | 110 (34.5) |

| 1998-2008 | 748 (38.1) | 41 (16.3) |

| Anthracycline-containing chemotherapyb | ||

| No doxorubicin and no epirubicin | 692 (35.2) | 128 (50.8) |

| Doxorubicin | 1,113 (56.7) | 111 (44.0) |

| Epirubicin and no doxorubicin | 159 (8.1) | 13 (5.2) |

| Cumulative doxorubicin dosec | ||

| No doxorubicin | 851 (43.3) | 141 (56.0) |

| 1-200 mg/m2 (median 150 mg/m2) | 448 (22.8) | 38 (15.1) |

| 201-349 mg/m2 (median 250 mg/m2) | 532 (27.1) | 66 (26.2) |

| 350-700 mg/m2 (median 400 mg/m2) | 89 (4.5) | 5 (2.0) |

| Unknown dose | 44 (2.2) | 2 (0.8) |

| Chest radiotherapyd | ||

| No chest RT | 388 (19.8) | 23 (9.1) |

| Mediastinal field, not including axilla | 609 (31.0) | 45 (17.9) |

| Mantle field or RT including axillary field(s) | 932 (47.5) | 176 (69.8) |

| Unspecified RT fields | 35 (1.8) | 8 (3.2) |

| Gonadotoxic treatmente | ||

| No procarbazine and no pelvic RT | 967 (49.2) | 128 (50.8) |

| Procarbazine ≤4.2 g/m2 (cumulative dise), no pelvic RT | 427 (21.7) | 60 (23.8) |

| Procarbazine 4.3-8.4 g/m2 (cumulative dose), no pelvic RT | 302 (15.4) | 40 (15.9) |

| Procarbazine >8.4 g/m2 (cumulative dose), no pelvic RT | 96 (4.9) | 8 (3.2) |

| Pelvic RT, with/without procarbazine | 112 (5.7) | 10 (4.0) |

| No pelvic RT, unknown CT/procarbazine dose | 60 (3.1) | 6 (2.4) |

| Follow-up duration, years | ||

| 5-9 | 155 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| 10-19 | 684 (34.8) | 33 (13.1) |

| 20-29 | 846 (43.1) | 142 (56.4) |

| ≥30 | 279 (14.2) | 77 (30.6) |

| Vital status at the end of follow-up | ||

| Alive | 1,519 (77.3) | 177 (70.2) |

| Deceased | 445 (22.7) | 75 (29.8) |

Abbreviations: ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; BC, breast cancer; BEACOPP, bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; CT, chemotherapy; EBVP, epirubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, and prednisone; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; MOPP, mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; MOPP-ABV, MOPP with doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vinblastine; RT, radiotherapy.

Either ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive BC, whichever occurred first.

One survivor treated without doxorubicin received mitoxantrone; one survivor received both doxorubicin and mitoxantrone; one survivor received doxorubicin and daunorubicin. Of all survivors who received epirubicin, 151 (88.9%) received six cycles of EBVP with a cumulative epirubicin dose of 420 mg/m2.

A doxorubicin dose of >200 mg/m2 corresponds to ≥6 cycles of MOPP-ABV, >4 cycles of ABVD, or ≥6 cycles of escalated BEACOPP.

The category no chest RT includes 58 survivors with RT limited to neck and 54 survivors with supraclavicular and/or infraclavicular fields (with or without neck). RT to the lung was also applied in 12 survivors in the mantle field category, in 19 survivors in the mediastinal RT category, and in one survivor in the unspecified RT category. Of all survivors categorized into unspecified RT, four survivors received supradiaphragmatic fields.

A procarbazine dose of ≤4.2 g/m2 corresponds to ≤3 MOPP cycles or ≤6 cycles of MOPP-ABV. A procarbazine dose of 4.3 to 8.4 g/m2 corresponds to 4-6 cycles of MOPP. A procarbazine dose of >8.4 g/m2 corresponds to >6 cycles of MOPP.

After a median follow-up of 21.6 years (IQR, 15.8-27.1 years), 252 women developed BC, 51 of whom had DCIS as a first BC event (Data Supplement, Table S3). The median interval between HL treatment and BC diagnosis was 19.9 years (IQR, 15.9-24.9 years) and the median age at BC diagnosis was 45.8 years (IQR, 40.6-51.8 years).

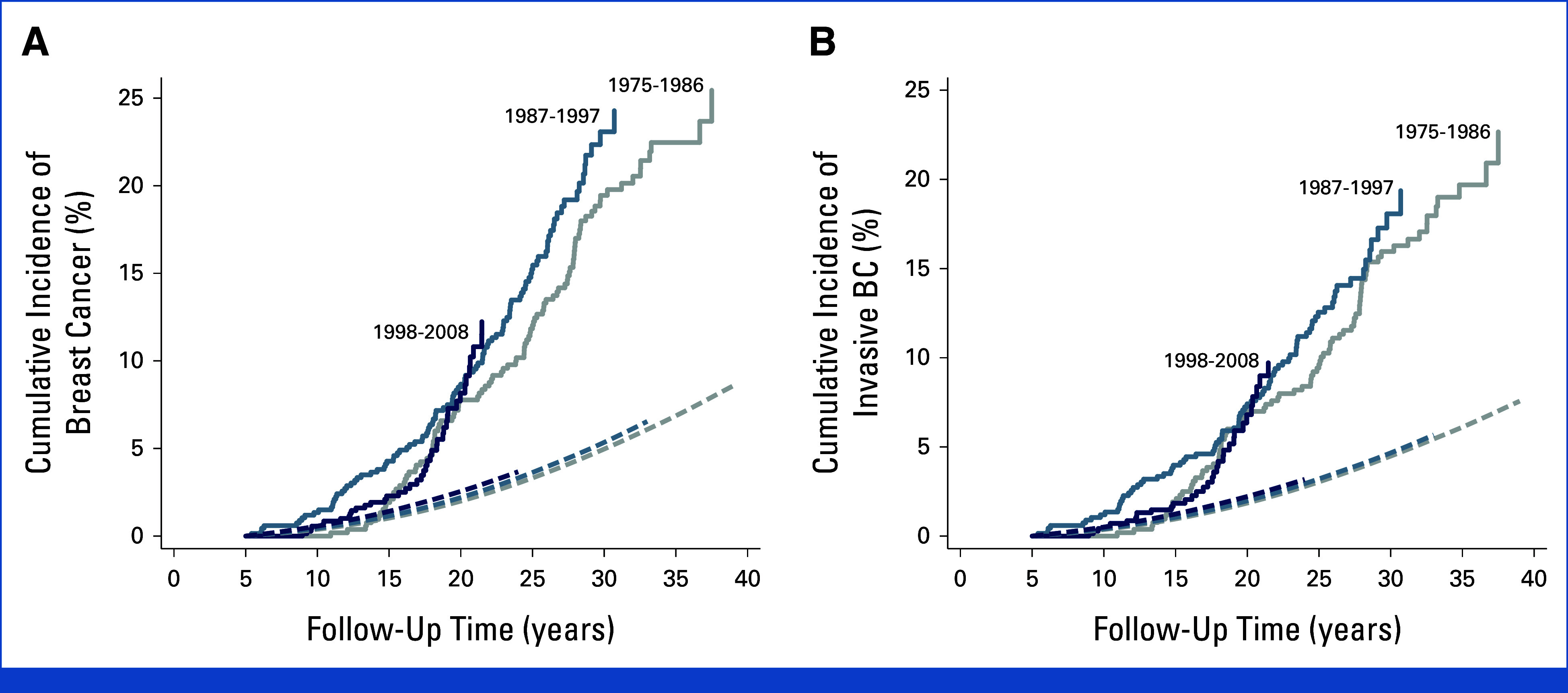

The cumulative 30-year BC incidence was 20.8% (95% CI, 18.2 to 23.4), while a cumulative incidence of approximately 5% was expected on the basis of Dutch general population incidence rates (Fig 1). Cumulative BC incidence did not differ between treatments periods; the 20-year cumulative incidences were 7.8% (95% CI, 5.7 to 10.3), 8.7% (95% CI, 6.6 to 11.0), and 8.2% (95% CI, 5.6 to 11.3) for survivors treated between 1975 and 1986, between 1987 and 1997, and between 1998 and 2008, respectively.

FIG 1.

(A) Cumulative incidence of BC in female 5-year HL survivors according to HL treatment period. Solid lines represent the cumulative incidence of invasive BC and DCIS in our cohort, stratified by period of HL treatment (Pheterogeneity = .53). Dashed lines represent the expected incidence of invasive BC and DCIS in the Dutch general population, stratified by the same periods. (B) Cumulative incidence of invasive BC in female HL survivors according to HL treatment period. Solid lines represent the cumulative incidence of invasive BC in our cohort, stratified by period of HL treatment (Pheterogeneity = .65). Dashed lines represent the expected incidence of invasive BC in the general population, stratified by the same periods. BC, breast cancer; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma.

Compared with the female general population, HL survivors experienced a 4.4-fold (95% CI, 3.9 to 5.0) increased BC risk, translating into an AER of 63.5 BCs per 10,000 person-years. SIRs in all treatment periods increased in the first 15 years of follow-up and then stabilized (Data Supplement, Fig S1). SIRs for BC strongly decreased with older age at diagnosis and were 17.8 (95% CI, 14.0 to 22.3), 6.7 (95% CI, 5.5 to 8.10), and 1.9 (95% CI, 1.4 to 2.4) for survivors age younger than 21 years, 21-30 years, and 31-50 years at HL treatment, respectively. Among doxorubicin-treated survivors, SIRs were significantly increased after ≥20 years of follow-up, but not in the 5-19 years of follow-up interval (adjusted for chest RT and gonadotoxic treatment, Pinteraction = .001; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

SIR and Absolute Excess Risk of BC, by HL Treatment and Attained Follow-Up

| Doxorubicin | Chest RT | Gonadotoxic Treatment, Cumulative Dose | 5-19 Years of Follow-Up | ≥20 Years of Follow-Up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totala | BC | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) | Totala | BC | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) | |||

| No doxorubicin | No chest RT | No pelvic RT and ≤4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 56 | 3 | 2.6 (0.5 to 7.7) | 26.0 (–7.3 to 106.8) | 27 | 1 | 3.1 (0.1 to 17.0) | 61.7 (–27.7 to 481.2) |

| No chest RT | Pelvic RT or >4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 51 | 0 | — | — | 38 | 3 | 2.5 (0.5 to 7.4) | 52.8 (–16.2 to 219.9) | |

| Mediastinal RT | No pelvic RT and ≤4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 74 | 2 | 1.1 (0.1 to 4.0) | 1.9 (–15.5 to 53.6) | 39 | 3 | 4.0 (0.8 to 11.8) | 104.2 (–5.7 to 370.5) | |

| Mediastinal RT | Pelvic RT or >4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 58 | 1 | 0.9 (0.0 to 5.0) | –1.8 (–15.5 to 62.8) | 36 | 0 | — | — | |

| MF/axillary RT | No pelvic RT and ≤4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 403 | 52 | 7.0 (5.2 to 9.2) | 83.1 (58.5 to 113.3) | 273 | 45 | 6.7 (4.9 to 8.9) | 182.8 (124.6 to 255.4) | |

| MF/axillary RT | Pelvic RT or >4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 169 | 11 | 3.5 (1.7 to 6.2) | 35.1 (10.4 to 74.0) | 119 | 13 | 3.9 (2.1 to 6.6) | 94.9 (35.1 to 185.9) | |

| Doxorubicin | No chest RT | No pelvic RT and ≤4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 196 | 8 | 2.5 (1.1 to 4.8) | 24.4 (1.0 to 64.4) | 38 | 0 | — | — |

| No chest RT | Pelvic RT or >4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 71 | 2 | 1.4 (0.2 to 5.1) | 7.1 (–14.0 to 70.0) | 40 | 4 | 5.2 (1.4 to 13.3) | 142.2 (14.0 to 417.0) | |

| Mediastinal RT | No pelvic RT and ≤4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 411 | 20 | 2.8 (1.7 to 4.3) | 26.2 (10.2 to 48.6) | 153 | 15 | 8.3 (4.7 to 13.7) | 221.0 (110.4 to 384.0) | |

| Mediastinal RT | Pelvic RT or >4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 57 | 1 | 1.0 (0.0 to 5.7) | 0.3 (–13.2 to 63.8) | 35 | 3 | 5.0 (1.0 to 14.5) | 119.8 (0.7 to 408.4) | |

| MF/axillary RT | No pelvic RT and ≤4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 230 | 17 | 3.8 (2.2 to 6.1) | 42.9 (18.6 to 78.0) | 128 | 17 | 8.2 (4.8 to 13.1) | 232.5 (121.9 to 391.7) | |

| MF/axillary RT | Pelvic RT or >4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 99 | 6 | 4.5 (1.6 to 9.8) | 43.3 (8.0 to 108.7) | 48 | 13 | 16.0 (8.5 to 27.4) | 453.1 (227.2 to 796.3) | |

NOTE. SIRs were calculated if at least one BC was observed.

Abbreviations: AER, absolute excess risk; BC, number of breast cancers observed; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma, MF/axillary RT, mantle field or RT including axillary field(s); RT, radiotherapy; SIR standardized incidence ratio.

Total number of observations exceed total number of survivors in the cohort, as survivors can contribute person-time to both the time interval <20 years and ≥20 years after diagnosis.

Compared with survivors who did not receive doxorubicin (43.3%), survivors treated with doxorubicin had a 1.4-fold (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.9) increased hazard of BC (adjusted for age at HL diagnosis, chest RT, and gonadotoxic treatment; Table 3, model A). The hazard ratios (HRs) for BC in survivors treated with 1-200 mg/m2 or >200 mg/m2 doxorubicin were 1.4 (95% CI, 0.9 to 2.0) and 1.5 (95% CI, 1.08 to 2.1), respectively, compared with survivors not treated with doxorubicin (Table 3, model B). Each 100 mg/m2 increase in doxorubicin dose was associated with a 1.18-fold increase in BC risk (95% CI, 1.05 to 1.32; Table 3, model C). In an analysis that only included survivors who had received doxorubicin (n = 1,113), the HR for BC associated with a 100 mg/m2 increase in doxorubicin dose (HR, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.92 to 1.56]; Data Supplement, Table S4) was very similar, albeit no longer statistically significant (Ptrend = .18). Receipt of epirubicin was not associated with BC risk (HR, 0.8 [95% CI, 0.4 to 1.5]). Survivors treated with MF/axillary RT had a 2.1-fold (95% CI, 1.3 to 3.3) increased BC risk compared with survivors not treated with chest RT; BC risk was not increased in survivors treated with mediastinal RT (HR, 1.0 [95% CI, 0.6 to 1.8]). A procarbazine dose of >8.4 g/m2 or receipt of pelvic RT was associated with decreased BC risk (HR, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.3 to 0.9]).

TABLE 3.

Treatment-Related Risk Factors for Subsequent BC in Female 5-Year Survivors of Hodgkin Lymphoma: Results From Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis

| Treatment Variable | Total (N = 1,964), No. (%) | BC Events (n = 252), No. | Model A, HR (95% CI) | Model B, HR (95% CI) | Model C, HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin | |||||

| No | 851 (43.3) | 141 | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 1,113 (56.7) | 111 | 1.4 (1.04 to 1.9) | ||

| Doxorubicin dose, mg/m2a | |||||

| No doxorubicin | 851 (43.3) | 141 | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| 1-200 | 448 (22.8) | 38 | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.0) | ||

| 201-700 | 621 (31.6) | 71 | 1.5 (1.08 to 2.1) | ||

| Unknown dose | 44 (2.2) | 2 | — | ||

| Doxorubicin dose (continuous) | |||||

| No doxorubicin | 851 (43.3) | 141 | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| Doxorubicin dose (per 100 mg/m2) | 1,069 (54.4) | 109 | 1.18 (1.05 to 1.32) | ||

| Unknown doxorubicin dose | 44 (2.2) | 2 | — | ||

| Chest radiotherapyb | |||||

| No chest RT | 388 (19.8) | 23 | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Mediastinum, not including axilla | 609 (31.0) | 45 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) |

| Mantle field or RT including axillary field(s) | 932 (47.5) | 176 | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.3) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.4) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.4) |

| Unspecified RT fields | 35 (1.8) | 8 | 2.8 (1.2 to 6.5) | 3.1 (1.3 to 7.2) | 3.2 (1.3 to 7.4) |

| Gonadotoxic treatmentc | |||||

| No pelvic RT and ≤4.2 g/m2 procarbazine | 1,394 (71.0) | 188 | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| No pelvic RT and 4.3-8.4 g/m2 procarbazine | 302 (15.4) | 40 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) |

| Pelvic RT or >8.4 g/m2 procarbazine | 208 (10.6) | 18 | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) |

| No pelvic RT and unknown CT or procarbazine dose | 60 (3.1) | 6 | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.98) | 0.7 (0.2 to 2.0) | 0.7 (0.2 to 1.9) |

NOTE. Analyses were stratified for age at first HL treatment (continuous). Lower limits of 95% CIs were rounded down, upper limits were rounded up. For doxorubicin-treated survivors, the median dose was 210 mg/m2 (IQR, 175-300 mg/m2). For doxorubicin-treated survivors with an event, the median dose was 210 mg/m2 (IQR, 200-280 mg/m2).

Abbreviations: ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; BC, breast cancer; BEACOPP, bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; CT, chemotherapy; MOPP, mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; MOPP-ABV, MOPP with doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vinblastine; RT, radiotherapy.

A doxorubicin dose of >200 mg/m2 corresponds to ≥6 cycles of MOPP-ABV, >4 cycles of ABVD, or ≥6 cycles of escalated BEACOPP.

The category no chest RT includes 58 survivors with RT limited to the neck and 54 survivors with supraclavicular and/or infraclavicular fields (with or without neck). RT to the lung was also applied in 12 survivors in the mantle field category, in 19 survivors in the mediastinal RT category, and in one survivor in the unspecified RT category. Of all survivors categorized into unspecified RT, four survivors received supradiaphragmatic fields.

A procarbazine dose of ≤4.2 g/m2 corresponds to ≤3 MOPP cycles or ≤6 cycles of MOPP-ABV. A procarbazine dose of 4.3 to 8.4 g/m2 corresponds to 4-6 cycles of MOPP. A procarbazine dose of >8.4 g/m2 corresponds to >6 cycles of MOPP.

The association between doxorubicin and BC risk differed by time since HL treatment, with increased BC risk limited to the follow-up interval ≥20 years after first HL treatment (HR≥20 years follow-up, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.4 to 3.2] Pinteraction = .004; Fig 2). When doxorubicin was included in the model using dose categories, this effect modification by time was also present (HR1-200 mg/m2, <20 years follow-up, 1.0 [95% CI, 0.5 to 1.6]; HR1-200 mg/m2, ≥20 years follow-up, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.1 to 3.9]; HR>200 mg/m2, <20 years follow-up, 1.0 [95% CI, 0.6 to 1.5]; HR>200 mg/m2, ≥20 years follow-up, 2.4 [95% CI, 1.5 to 3.7], Pinteraction = .006; Data Supplement, Table S5). Gonadotoxic treatment also appeared to modify the association of doxorubicin with BC risk, although this was not statistically significant (HRwith gonadotoxic treatment, 2.2 [95% CI, 1.2 to 3.8] HRwithout gonadotoxic treatment, 1.2 [95% CI, 0.8 to 1.8] Pinteraction = .08). There was no significant effect modification by age at HL treatment; the HRage <21 years was 1.5 [95% CI, 0.9 to 2.6] and HRage ≥21 years 1.3 [95% CI, 0.9 to 1.9]). Receipt of MF/axillary RT did also not significantly modify the association between doxorubicin and BC risk (HRwithout MF/axillary RT 1.9 [95% CI, 1.06 to 3.3]; HRwith MF/axillary RT, 1.2 [95% CI, 0.8 to 1.8]).

FIG 2.

Doxorubicin and BC risk: results from multivariable Cox regression interaction analysis. Doxorubicin and BC risk, according to age at treatment, mantle or axillary field RT, gonadotoxic treatment and follow-up interval: results from multivariable Cox regression interaction analysis. All models were adjusted for chest radiotherapy, gonadotoxic treatment, and stratified for age at HL treatment. aSurvivors with unknown procarbazine dose are not shown (n = 60 with six events). bNumbers of observations exceed total number of survivors in the cohort, as survivors can contribute person-time to both the time interval <20 years and ≥20 years after diagnosis. The model including an interaction term of doxorubicin with time since treatment, and doxorubicin and gonadotoxic treatment, was not better than a model only including interaction of doxorubicin with time since treatment (Plikelihood ratio test = .14). The model including an interaction term of doxorubicin with mantle/axillary field RT, and doxorubicin and gonadotoxic treatment, was not better than a model only including interaction of doxorubicin with mantle/axillary field RT (Plikelihood ratio test = .10). BC, breast cancer; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; MF/axillary RT, mantle field or radiotherapy including axillary field(s).

Similar results were obtained in analyses excluding DCIS, or excluding all survivors with missing data on treatment variables, or when reclassifying survivors treated with lung RT to the MF/axillary RT category (Data Supplement, Tables S6-S8). The results of a sensitivity analysis restricted to survivors treated in the period between 1989 and 2008 were very similar to the results obtained for the full cohort (Data Supplement, Table S9).

DISCUSSION

This large cohort study with detailed information on primary and relapse treatment, and near-complete, long-term follow-up for subsequent BCs shows that doxorubicin exposure in HL survivors treated at age 15-50 years is associated with a 1.4-fold increased BC risk. This increased risk was independent of age at first HL treatment and receipt of chest RT. In accordance with previous studies, BC risk was lower for survivors treated with radiation limited to the mediastinum compared with MF or axillary field irradiation.1,2 However, despite lower chest RT volumes and doses in more contemporary HL treatment regimens, neither cumulative BC incidence nor SIRs declined in more recently treated patients. This suggests that other changes in HL treatment policy counteract the effects of less toxic RT regimens.

The absence of a decline in BC incidence in more recently treated HL survivors may partly result from the decreased use of gonadotoxic treatments. As shown previously, a premature menopause, caused by gonadotoxic chemotherapy or pelvic RT, substantially decreases the risk of radiation-associated BC.1,2,10,31 A second major change over the past decades is the increased use of the anthracycline doxorubicin. Doxorubicin can cause malignant transformation and mutations in vitro and has been associated with an increased risk of acute myeloid leukemia in humans.32,33 Doxorubicin causes DNA damage by inducing double-strand breaks, and chromatin damage through histone eviction in the genome, which may explain its carcinogenicity.34 Animal studies support an anthracycline-BC association, with positive findings in mice and rats.3,34-37 An association between anthracyclines and increased BC risk has been reported in three CCS cohorts.18-22 The study in Dutch CCS reported that doxorubicin was associated with a dose-dependent increase in BC risk with HRs of 1.1, 2.6, and 5.8 for survivors who had received doxorubicin doses of ≤270 mg/m2, 271-443 mg/m2, and >443 mg/m2, respectively (Ptrend<0.001).19 We also found a significantly increased BC risk in survivors treated with a doxorubicin dose >200 mg/m2 (HR, 1.5 [95% CI, 1.08 to 2.1]) and an increasing BC risk with increasing doxorubicin dose (HR, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.05 to 1.32] per 100 mg/m2 increase in doxorubicin dose). When dose-response analyses were restricted to survivors treated with doxorubicin, the dose-response relationship was no longer statistically significant, but the HR point estimate for each 100 mg/m2 increase in doxorubicin dose did not differ from the HR on the basis of analyses including survivors not treated with doxorubicin (HR, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.92 to 1.56]). Our findings corroborate the carcinogenic potential of doxorubicin and suggest that the increased use of doxorubicin may partly explain why HL survivors treated in more recent years do not experience lower BC risk than survivors treated before the 1990s, when MF irradiation was widely used.17

BC surveillance for female survivors treated with MF irradiation was gradually introduced in several Dutch hospitals between 1996 and 2010, because of increased awareness of increased BC risk in these survivors.24,38,39 Mammography-based screening was offered to women treated with chest RT from age 25 years (≥8 years after treatment),40 which led to a greater proportion of DCIS diagnoses among the BCs detected in our population. A gradual increase in BC incidence, associated with increasing screening uptake in more recent years, might introduce a spurious association with doxorubicin exposure, as use of doxorubicin increased in the same time period. However, in an analysis restricted to invasive BC, results were very similar to our main analysis on the basis of all BC events. Additionally, the association between doxorubicin exposure and BC was slightly stronger among survivors not treated with chest RT. As these women were not eligible for BC screening, this argues against screening bias as an explanation for our results.

In two CCS studies, the BC risk increase and doxorubicin dose-response trend were stronger for CCS with primary tumors typically observed within the spectrum of the Li-Fraumeni (like) syndrome (LFS), such as leukemia, sarcoma, and brain tumors, compared with survivors of other solid tumors and lymphoma combined, which might indicate a gene-anthracycline interaction in the development of BC.18,19 Our findings show that the doxorubicin-BC association is not restricted to patients with LFS, as HL is not a LFS-associated malignancy. Additionally, the St Jude Lifetime cohort study recently showed that a higher anthracycline dose is associated with increased BC risk independent of mutations in known cancer predisposition genes.22 Nevertheless, further research is needed to assess whether genetic or metabolic factors may play a role in the doxorubicin-BC association.

In our study, epirubicin treatment was not associated with increased BC risk; however, only few survivors (159 females, of whom six developed BC) received anthracycline-containing regimens with epirubicin alone, many of whom were enrolled in the EORTC H7 trial that aimed to reduce toxicity without jeopardizing efficacy.41 The low number of survivors treated with epirubicin resulted in a low number of BCs. The upper confidence bound of our effect estimate does not preclude an increased risk associated with epirubicin exposure.

The association of doxorubicin with BC risk appeared to be present only in the interval ≥20 years after HL treatment and not in the interval 5-19 years after treatment. Increased SIRs were also limited to survivors with ≥20 years of follow-up compared with survivors with <20 years of follow-up. This may reflect an anthracycline-associated induction period for BC.

Our study included survivors from a broad treatment period and therefore takes into account the change from extended-field RT to involved-field RT. Importantly, RT regimens have significantly evolved since 2006, when the involved site/node principle was introduced and modern RT techniques, such as intensity-modulated RT or deep inspirational breath hold, were also applied to patients with HL.42 These therapies enable significant reductions of exposure of normal tissues to radiation43; therefore, a reduction in radiation-associated BC risk is expected. In balancing treatment efficacy and toxicity, studies have focused on omitting RT and trying to cure patients with early-stage HL with chemotherapy alone.44-47 Doxorubicin-associated BC risk may be an additional late effect that needs to be considered when weighing risks and benefits of chemotherapy only versus combined modality in primary treatment.

Our study has some limitations. Doxorubicin is commonly given in standard combinations with bleomycin and vinblastine (eg, ABV). Although there is little evidence for carcinogenicity in humans because of bleomycin or vinblastine,32 we could not distinguish the effect of doxorubicin from other agents. A large proportion of HL survivors had received chest RT, which made it challenging to fully separate associations between doxorubicin and BC and chest RT and BC. However, mantle or axillary field irradiation did not modify the association between doxorubicin and BC risk. In our analyses, doxorubicin and procarbazine doses were based on standard regimen doses and number of chemotherapeutic cycles; data on dose reductions were not systematically collected. However, in previous case-control studies in our cohort,10 dose reductions occurred infrequently. Duration of ovarian function after HL treatment would probably have been a better indicator of individual gonadotoxicity than receipt of gonadotoxic treatment; however, information on menopausal age was incomplete for a large part of the cohort.

In conclusion, our study suggests that adolescent and adult female 5-year HL survivors treated with doxorubicin have an increased risk of BC, which is independent of age at first HL treatment, receipt of chest RT, and gonadotoxic treatment. Female patients with HL receiving more contemporary treatments continue to have an increased BC risk compared with the general population, despite efforts to limit radiation-associated subsequent cancers. Our study shows that it remains of great importance to follow patients for more than 20 years after their treatment has been completed. Our findings confirm the importance of risk-based long-term follow-up care for lymphoma survivors and possibly survivors of other cancers treated with doxorubicin. Our results are also relevant for treatment strategies for patients with newly diagnosed HL, when balancing the risks and benefits of systemic therapy and RT. Since effective novel agents (eg, antibody-drug conjugates and immune checkpoint inhibitors) have been introduced in the treatment for patients with HL,48 future clinical trials should also aim at reducing the dose of doxorubicin. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effect of doxorubicin on BC risk in the absence of chest RT in more recently treated patient cohorts and to assess the role of genetic susceptibility in the development of doxorubicin-associated BC.

Berthe M.P. Aleman

Honoraria: MSD (Inst)

Pieternella J. Lugtenburg

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche/Genentech, Genmab, Regeneron, Incyte, AbbVie, Y-mAbs Therapeutics

Speakers' Bureau: Lilly, AbbVie

Research Funding: Takeda (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene

Roel J. de Weijer

Honoraria: Amgen (Inst)

Marie José Kersten

Honoraria: Kite, a Gilead company, Roche, AbbVie/Genentech, BMS

Consulting or Advisory Role: Kite, a Gilead Company, Miltenyi Biotec (Inst), Adicet BIo

Research Funding: Kite, a Gilead company (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Kite, a Gilead Company, AbbVie

Lara H. Böhmer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AbbVie

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

See accompanying Editorial, p. 1868

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented at the 2021 ASCO Annual Meeting, virtual, June 4, 2021; at the International Symposium on Late Complication after Childhood Cancer (ISLCCC), Utrecht, the Netherlands, July 8, 2022; and at the International Symposium Hodgkin Lymphoma (ISHL), Cologne, Germany, October 23, 2022.

SUPPORT

Supported by grant No. NKI 2010-4720 and NKI 2016-10424 from the Dutch Cancer Society, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

F.E.V.L. and M.S. contributed equally to this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Suzanne I.M. Neppelenbroek, Berthe M.P. Aleman, Marie José Kersten, Flora E. van Leeuwen, Michael Schaapveld

Financial support: Michael Schaapveld

Provision of study materials or patients: Berthe M.P. Aleman, Pieternella J. Lugtenburg, Saskia E. Rademakers, Roel J. de Weijer, Maaike G.A. Schippers, Bastiaan D.P. Ta, Wouter J. Plattel, Josée M. Zijlstra, Richard W.M. van der Maazen, Francisca Ong, Erik C. Schimmel, Eduardus F.M. Posthuma, Marie José Kersten, Lara H. Böhmer, Harry R. Koene, Yavuz M. Bilgin, Cécile P.M. Janus

Collection and assembly of data: Suzanne I.M. Neppelenbroek, Pieternella J. Lugtenburg, Saskia E. Rademakers, Roel J. de Weijer, Maaike G.A. Schippers, Bastiaan D.P. Ta, Wouter J. Plattel, Josée M. Zijlstra, Richard W.M. van der Maazen, Marten R. Nijziel, Francisca Ong, Erik C. Schimmel, Eduardus F.M. Posthuma, Lara H. Böhmer, Karin Muller, Harry R. Koene, Liane C.J. te Boome, Yavuz M. Bilgin, Cécile P.M. Janus, Michael Schaapveld

Data analysis and interpretation: Suzanne I.M. Neppelenbroek, Yvonne M. Geurts, Berthe M.P. Aleman, Bastiaan D.P. Ta, Richard W.M. van der Maazen, Marten R. Nijziel, Marie José Kersten, Yavuz M. Bilgin, Eva de Jongh, Flora E. van Leeuwen, Michael Schaapveld

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Doxorubicin Exposure and Breast Cancer Risk in Survivors of Adolescent and Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Berthe M.P. Aleman

Honoraria: MSD (Inst)

Pieternella J. Lugtenburg

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche/Genentech, Genmab, Regeneron, Incyte, AbbVie, Y-mAbs Therapeutics

Speakers' Bureau: Lilly, AbbVie

Research Funding: Takeda (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene

Roel J. de Weijer

Honoraria: Amgen (Inst)

Marie José Kersten

Honoraria: Kite, a Gilead company, Roche, AbbVie/Genentech, BMS

Consulting or Advisory Role: Kite, a Gilead Company, Miltenyi Biotec (Inst), Adicet BIo

Research Funding: Kite, a Gilead company (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Kite, a Gilead Company, AbbVie

Lara H. Böhmer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AbbVie

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.De Bruin ML, Sparidans J, van't Veer MB, et al. : Breast cancer risk in female survivors of Hodgkin's lymphoma: Lower risk after smaller radiation volumes. J Clin Oncol 27:4239-4246, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow AJ, Cooke R, Bates A, et al. : Breast cancer risk after supradiaphragmatic radiotherapy for Hodgkin's lymphoma in England and Wales: A national cohort study. J Clin Oncol 30:2745-2752, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Leeuwen FE, Ronckers CM: Anthracyclines and alkylating agents: New risk factors for breast cancer in childhood cancer survivors? J Clin Oncol 34:891-894, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenney LB, Yasui Y, Inskip PD, et al. : Breast cancer after childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Intern Med 141:590-597, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatia S, Yasui Y, Robison LL, et al. : High risk of subsequent neoplasms continues with extended follow-up of childhood Hodgkin's disease: Report from the Late Effects Study Group. J Clin Oncol 21:4386-4394, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. : Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:2217-2223, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Travis LB, Hill D, Dores GM, et al. : Cumulative absolute breast cancer risk for young women treated for Hodgkin lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:1428-1437, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inskip PD, Robison LL, Stovall M, et al. : Radiation dose and breast cancer risk in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 27:3901-3907, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Bruin ML, Huisbrink J, Hauptmann M, et al. : Treatment-related risk factors for premature menopause following Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 111:101-108, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krul IM, Opstal-van Winden AWJ, Aleman BMP, et al. : Breast cancer risk after radiation therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma: Influence of gonadal hormone exposure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 99:843-853, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canellos GP, Anderson JR, Propert KJ, et al. : Chemotherapy of advanced Hodgkin's disease with MOPP, ABVD, or MOPP alternating with ABVD. N Engl J Med 327:1478-1484, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonadonna G, Zucali R, Monfardini S, et al. : Combination chemotherapy of Hodgkin's disease with adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and imidazole carboxamide versus MOPP. Cancer 36:252-259, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raemaekers JM, van der Maazen RW: Hodgkin's lymphoma: News from an old disease. Neth J Med 66:457-466, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engert A, Franklin J, Eich HT, et al. : Two cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine plus extended-field radiotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in early favorable Hodgkin's lymphoma: Final results of the GHSG HD7 trial. J Clin Oncol 25:3495-3502, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engert A, Schiller P, Josting A, et al. : Involved-field radiotherapy is equally effective and less toxic compared with extended-field radiotherapy after four cycles of chemotherapy in patients with early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin's lymphoma: Results of the HD8 trial of the German Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 21:3601-3608, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fermé C, Eghbali H, Meerwaldt JH, et al. : Chemotherapy plus involved-field radiation in early-stage Hodgkin's disease. N Engl J Med 357:1916-1927, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaapveld M, Aleman BM, van Eggermond AM, et al. : Second cancer risk up to 40 years after treatment for Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 373:2499-2511, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson TO, Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, et al. : Breast cancer risk in childhood cancer survivors without a history of chest radiotherapy: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 34:910-918, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teepen JC, van Leeuwen FE, Tissing WJ, et al. : Long-term risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms after treatment of childhood cancer in the DCOG LATER study cohort: Role of chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 35:2288-2298, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veiga LH, Curtis RE, Morton LM, et al. : Association of breast cancer risk after childhood cancer with radiation dose to the breast and anthracycline use: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA Pediatr 173:1171-1179, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turcotte LM, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. : Chemotherapy and risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol 37:3310-3319, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehrhardt MJ, Howell CR, Hale K, et al. : Subsequent breast cancer in female childhood cancer survivors in the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). J Clin Oncol 37:1647-1656, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Leeuwen FE, Klokman WJ, Hagenbeek A, et al. : Second cancer risk following Hodgkin's disease: A 20-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 12:312-325, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Leeuwen FE, Klokman WJ, Veer MB, et al. : Long-term risk of second malignancy in survivors of Hodgkin's disease treated during adolescence or young adulthood. J Clin Oncol 18:487-497, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aleman BM, van den Belt-Dusebout AW, Klokman WJ, et al. : Long-term cause-specific mortality of patients treated for Hodgkin's disease. J Clin Oncol 21:3431-3439, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Bruin ML, Burgers JA, Baas P, et al. : Malignant mesothelioma after radiation treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 113:3679-3681, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schouten LJ, Höppener P, van den Brandt PA, et al. : Completeness of cancer registration in Limburg, The Netherlands. Int J Epidemiol 22:369-376, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Willik KD, Ruiter R, van Rooij FJA, et al. : Ascertainment of cancer in longitudinal research: The concordance between the Rotterdam Study and The Netherlands Cancer Registry. Int J Cancer 147:633-640, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breslow NE, Day NE: Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume II—The design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ 82:1-406, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fine JP, Gray RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94:496-509, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer : Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: Individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol 13:1141-1151, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Overall evaluations of carcinogenicity: An updating of IARC Monographs volumes 1 to 42. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum Suppl 7:1-440, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marquardt H, Philips FS, Sternberg SS: Tumorigenicity in vivo and induction of malignant transformation and mutagenesis in cell cultures by adriamycin and daunomycin. Cancer Res 36:2065-2069, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiao X, van der Zanden SY, Wander DPA, et al. : Uncoupling DNA damage from chromatin damage to detoxify doxorubicin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:15182-15192, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price PJ, Suk WA, Skeen PC, et al. : Transforming potential of the anticancer drug adriamycin. Science 187:1200-1201, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solcia E, Ballerini L, Bellini O, et al. : Mammary tumors induced in rats by adriamycin and daunomycin. Cancer Res 38:1444-1446, 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bucclarelli E: Mammary tumor induction in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats by adriamycin and daunomycin. J Natl Cancer Inst 66:81-84, 1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swerdlow AJ, Barber JA, Hudson GV, et al. : Risk of second malignancy after Hodgkin's disease in a collaborative British cohort: The relation to age at treatment. J Clin Oncol 18:498-509, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ng AK, Bernardo MV, Weller E, et al. : Second malignancy after Hodgkin disease treated with radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy: Long-term risks and risk factors. Blood 100:1989-1996, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nijdam A, Dekker N, Aleman BMP, et al. : Setting up a national infrastructure for survivorship care after treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol 186:e103-e108, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noordijk EM, Carde P, Dupouy N, et al. : Combined-modality therapy for clinical stage I or II Hodgkin's lymphoma: Long-term results of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer H7 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 24:3128-3135, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Specht L, Yahalom J, Illidge T, et al. : Modern radiation therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma: Field and dose guidelines from the international lymphoma radiation oncology group (ILROG). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 89:854-862, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milgrom SA, Bakst RL, Campbell BA: Clinical outcomes confirm conjecture: Modern radiation therapy reduces the risk of late toxicity in survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 111:841-850, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.André MPE, Girinsky T, Federico M, et al. : Early positron emission tomography response–adapted treatment in stage I and II Hodgkin lymphoma: Final results of the randomized EORTC/LYSA/FIL H10 trial. J Clin Oncol 35:1786-1794, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franklin J, Eichenauer DA, Becker I, et al. : Optimisation of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for untreated Hodgkin lymphoma patients with respect to second malignant neoplasms, overall and progression-free survival: Individual participant data analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:Cd008814, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyer RM, Gospodarowicz MK, Connors JM, et al. : ABVD alone versus radiation-based therapy in limited-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 366:399-408, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radford J, Barrington S, Counsell N, et al. : Involved field radiotherapy versus No further treatment in patients with clinical stages IA and IIA Hodgkin lymphoma and a 'negative' PET scan after 3 cycles ABVD. Results of the UK NCRI RAPID trial. Blood 120:547, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vassilakopoulos TP, Liaskas A, Pereyra P, et al. : Incorporating monoclonal antibodies into the first-line treatment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Mol Sci 24:13187, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]