Abstract

Screening for autism in childhood has been advocated as a part of standard care. Challenges exist with screening implementation and performance of screening tools in clinical practice. This study aimed to examine the validity and feasibility of using the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F) for screening of autism in Singapore. Caregivers completed the M-CHAT-R/F as a part of the routine 18-month well-child visit in seven primary care clinics. Screening and follow-up interviews were administered by trained nursing staff. Children screened positive and a subset of those screened negative underwent diagnostic assessments for autism, which included an Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition. Participants were 5336 multiethnic children (mean age 18.6 ± 0.9 months, 51.3% male gender). In total, 113 (2.1%) were screened positive, of which 54 (1.0%) were classified to have autism after their diagnostic assessment. Sensitivity of the M-CHAT-R/F was 88.6%, specificity 71.4%, and positive predictive value 90.7% for an autism diagnosis. The majority of respondents rated the screening process as feasible within the clinic setting. The M-CHAT-R/F had acceptable psychometric properties and high feasibility when used in primary care settings in Singapore. Recommendations for implementation of systematic screening and future research are presented.

Lay abstract

Systematic screening for autism in early childhood has been suggested to improve eventual outcomes by facilitating earlier diagnosis and access to intervention. However, clinical implementation of screening has to take into account effectiveness and feasibility of use within a healthcare setting for accurate diagnosis of autism. In Singapore, autism screening using a structured screening tool is not currently employed as a part of routine well-child visits for children in primary care clinics. In this study, 5336 children (aged 17–20 months) were screened for autism using the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F) during their 18-month well-child visit in seven primary care clinics. Screening and follow-up interviews were administered by nursing staff at each clinic. Children screened positive and a portion of those screened negative then underwent diagnostic assessments to determine whether they met the diagnostic criteria for autism. In total, 113 (2.1%) were screened positive, of which 54 (1.0%) met the criteria for autism. Children who screened positive and received a diagnosis accessed autism-specific intervention at an average age of 22 months. Nurses and physicians rated the acceptability and practicality of the M-CHAT-R/F highly. Therefore, the M-CHAT-R/F questionnaire was an effective and feasible tool for autism screening among 18-month-old children in this study. Future studies will be designed to determine the optimal age of screening and role of repeated screening in Singapore, as well as to better understand any potential improved outcomes nationwide compared with pre-implementation of autism screening.

Keywords: autism, autism spectrum disorder, children, Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up, primary care, screening, M-CHAT-R/F

Introduction

Autism is one of the most common neurodevelopmental conditions in childhood characterized by persistent difficulties in social communication and behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Autism is increasing in prevalence with a recent systematic review estimating a median prevalence of 1%, but with wide geographic variation from 0.01% to 4.4% (Zeidan et al., 2022). The cost of autism at an individual, societal, and national level is high, due to the lifelong nature of the condition and its wide-ranging implications on educational attainment, adaptive and cognitive skills. Various studies including a global review have estimated a lifetime cost of between US$1.4 million and 2.4 million, (depending on factors such as presence of associated intellectual disability) to support an individual on the autism spectrum over the lifetime (Buescher et al., 2014; Rogge & Janssen, 2019). Another recent study from China, an Asian country, estimated the total annual cost to be US$34,206.50, which was 151% of the sample’s median household income (Zhao et al., 2023). Within Singapore, autism has been consistently ranked first among conditions with the highest impact in children between 0 and 14 years (Epidemiology & Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health Singapore, 2010; Phua et al., 2009).

The high diagnostic stability of an autism diagnosis in early childhood (Pierce et al., 2019; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2016) with the availability of effective interventions (Fuller et al., 2020; Rogers et al., 2019) has prompted numerous professional groups to recommend routine systematic screening for autism among low-risk children. For example, the American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) recommends routine autism screening at 18 and 24 months of age in all children as a part of standard primary care (Hyman et al., 2020). Screening for autism within the context of research studies has been shown to be sensitive and facilitates an earlier diagnosis of the condition (Robins et al., 2014; Sánchez-García et al., 2019). However, within primary care settings, implementation of systematic screening has challenges, including, but not limited to, disparity in access to screening, non-adherence to screening protocols, and high loss to follow-up of screen-positive patients (Guthrie et al., 2019; Khowaja et al., 2015; Wieckowski et al., 2021). Children from low-income and ethnically diverse families are less likely to attend well-child visits at primary care, and hence receive screening as recommended (Kuo et al., 2012). In different real-world studies, this same group of children, together with those whose native language was a non-English language, were more likely to not receive autism screening despite attending a well-child visit (Carbone et al., 2020; Guthrie et al., 2019; Wallis & Guthrie, 2020). Pediatricians have also been shown to omit the follow-up interview for some children due to time constraints during brief clinic visits, thereby leading to infidelity in screen administration (Carbone et al., 2020). Finally, access to a follow-up autism evaluation may be more complex in real-world settings due to long wait times and systemic barriers to access especially for minority communities, leading to lack of follow-through with recommended post-screening procedures (McKenzie et al., 2015). Performance of screening tools within clinics tends to show lower sensitivity compared with research settings (Carbone et al., 2020; Guthrie et al., 2019), raising concerns about the effectiveness of screening and potentially influencing implementation in other primary care networks.

The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F) is one of the most widely studied instruments for autism screening (Marlow et al., 2019). Apart from high sensitivity (0.83–0.85) and specificity (0.95–0.99) in the initial validation sample (Robins et al., 2014), the M-CHAT-R/F has been shown to have a high sensitivity of 0.83 (95% CI = 0.76–0.89) and acceptable positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.58 (95% CI = 0.49–0.67) in a global meta-analysis (Aishworiya et al., 2023). Another meta-analysis also showed an equally robust pooled sensitivity of 0.83 (95% CI = 0.77–0.88) and specificity of 0.94 (95% CI = 0.89–0.97) (Wieckowski et al., 2023). Previous studies that assessed the performance of the M-CHAT-R/F in China (Guo et al., 2019), Taiwan (Tsai et al., 2019), and Iran (Manzouri et al., 2019) showed acceptable performance of the M-CHAT-R/F, but either did not include feasibility data, had small sample size, or did not include evaluations of children who screened negative.

Successful implementation of systematic screening for autism must take into consideration the feasibility of use from healthcare professionals conducting screening. The performance of the screening tool within the clinical context should also be evaluated to assess validity. The aims of this study were to determine the validity and feasibility of M-CHAT-R/F as a screening tool for autism within well-child visits in primary care clinics.

Method

Study setting

The study was conducted in seven primary care clinics, also called polyclinics, under the National University Polyclinics in the western part of Singapore between August 2020 and November 2022. These clinics meet the needs of the pediatric population in the community by providing childhood immunizations, routine developmental screening, neonatal weight checks, and health promotion functions. The seven clinics serve approximately one-third of children within the country. Developmental screening practices prior to this study in these clinics rely primarily on the use of a set of questions loosely adapted from the Denver Developmental Screening Test (Lim et al., 1994) during well-child visits scheduled at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, 30, and 48 months of age. This is meant to aid physicians in eliciting developmental milestones. There is no scoring of responses or use of a specific protocol to dictate further evaluations; rates of completion of the questions have been shown to be low in a previous study (Koh et al., 2016). Questions pertaining to possible early features of autism (e.g. presence of response to name) are embedded within the clinical interview from 18 months onwards, but a structured autism screening tool is not utilized. At each visit, a primary care physician reviews the child’s development and children who have developmental concerns are referred to a tertiary child development unit (CDU); there are existing referral pathways as a part of the standard clinic workflows to facilitate this.

Ethical approval for the study and all related activities was obtained by the relevant institutional ethics review board prior to study commencement (DSRB Study No. 2019/00689). No members from the autism community (e.g. caregivers of children on the autism spectrum) were involved in the design of this study.

Study sample

Study participants were recruited from children who attended the 18-month-old well-child visit in any of the seven primary care clinics. We included children aged between 17 and 24 months, who were accompanied by caregivers (including parents, legal guardians, grandparents, or other relatives) who were conversant in and were able to read and write in English. English is the official language in Singapore and is spoken by a majority of the non-elderly population. Children were excluded from the study when they were reported to have known developmental disorders, attending a CDU, and/or receiving child developmental services. Prematurity or having a sibling on the autism spectrum were not exclusion criteria so as to intentionally keep the inclusion criteria broad, but this information was collected as a part of study measures.

Study procedure

Following administration of informed consent (by a study research staff or clinic nurse), caregivers who consented to participation completed the M-CHAT-R/F, in English, and a study demographics questionnaire (Supplemental Material 1). Following completion by the caregiver, the M-CHAT-R/F was scored immediately by the same person who administered it and a follow-up interview was conducted verbally when needed. The standard scoring protocol of the M-CHAT-R/F was employed. Children with a score of ⩽2 were considered to be at low risk and no further study-related action was required. Children who scored ⩾8 were classified to have a positive screen and at high risk. These children were offered a comprehensive evaluation by both a developmental–behavioral pediatrician (DBP) and a psychologist to ascertain whether a diagnosis of autism was warranted (see below). Children who scored between 3 and 7 were classified as medium risk and underwent a follow-up interview to clarify questions with an at-risk response. Those who scored ⩾2 after the interview were classified to also have a positive screen and were also referred for further evaluation.

Regardless of the M-CHAT-R/F score, the primary care physician who completed the well-child visit was asked to indicate whether he or she had any concerns for autism in each child, based on their observed developmental findings. The presence of any clinician concerns would automatically result in a referral to the CDU for these children (regardless of their M-CHAT-R/F screen status).

Diagnostic evaluation for autism

All children who were screened positive (initial M-CHAT-R/F score ⩾8 or post-interview score ⩾2) as well as those for whom the primary care physician had concerns for autism were offered a diagnostic evaluation at the CDU. The evaluation comprised two components to facilitate a comprehensive evaluation: clinical history and physical examination by a DBP and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al., 2012) by a psychologist. Caregivers were strongly encouraged to attend both components of the evaluation; however, given the stigma of seeing a psychologist in our culture, (Goh et al., 2021) caregivers who declined the ADOS-2 were given the option to only attend the pediatrician’s evaluation (instead of no evaluation at all).

The ADOS-2 (Lord et al., 2012) is a semi-structured standardized assessment that has been validated across a range of ages and is widely regarded as the “gold standard” in the assessment of autism. The ADOS-2 Toddler Module (ADOS-T) is intended for use in children below 30 months of age, with at least a nonverbal age equivalent of 12 months of age and who are walking independently (Luyster et al., 2009). The ADOS-T has been shown to have high predictive value for an autism diagnosis in later childhood (Lee et al., 2019; Luyster et al., 2009). In this study, the ADOS-T was administered by one of two research-reliable psychologists with good interrater reliability (85% agreement). Based on recommended scoring criteria (Hong et al., 2021; Luyster et al., 2009) children with a total score in the “moderate-to-severe concern” ranges were classified to have autism.

The DBP evaluation comprised a thorough medical and developmental history, which is intended to differentiate autism from other developmental disorders (e.g. developmental language delay or global developmental delay) based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (5th ed; DSM-5) criteria. This evaluation was conducted by one of the DBP physicians at the CDU, as assigned by standard clinic workflow. After the evaluation, the physician in the CDU made recommendations to parents and referred children to early intervention services according to their developmental profiles; children with an autism diagnosis would receive autism-specific behavioral therapy.

Evaluation of screen negative children

To evaluate the psychometric properties of the M-CHAT-R/F accurately, a randomly selected (based on computerized randomization of study ID) sample of children who screened negative in the M-CHAT-R/F were offered an ADOS-2 evaluation. Another random sample of participants with an initial negative M-CHAT-R/F screen were also followed-up via a telephone call 6 months following their screen. During the phone call, caregivers were asked whether the child had any new developmental concerns. They were also administered the communication domain of the 24 month Ages and Stages (ASQ) questionnaire (Squires et al., 2009). The ASQ, Third Edition (ASQ-3) is a broad developmental screening tool with good sensitivity and specificity and has been validated in multiple populations (Velikonja et al., 2017). Children for whom the caregiver had any developmental concerns, or who scored below the pass range in the ASQ were offered further diagnostic evaluations at the CDU. The number of children who were selected for the 6-month follow-up telephone call was identical to the number who were screened positive in the primary care clinics every month.

Feasibility of implementation

The study was initially conducted within one primary care clinic site over 1 month as a pilot to trial the study measures and workflows within the clinic setting. This initial primary care site did not vary from the other sites and was chosen at random. Following this first month, the study was then rolled out to all the clinics involved. Together with research staff, all healthcare nurses and physicians across the primary care clinics involved in the study underwent two training sessions on the M-CHAT-R/F. These sessions were conducted by the lead study team members (a DBP and a primary care physician). The first session was conducted prior to the pilot trial and the second session after the pilot; both sessions were conducted online via a virtual medium due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic restrictions at that time. The contents of the training included information on autism, early signs of autism in young children, the background and development of the M-CHAT-R/F questionnaire, administration of the questionnaire and the follow-up interview guide, intervention options available for autism in the study setting, as well as study-related workflows in terms of informed consent taking and further follow-up of children who participated in the study. Sessions also included a role-play segment with modeling of the questionnaire administration, administering specific follow-up interview questions for each question and on counseling caregivers following a positive screen. While both sessions had specific time set aside for participants to ask questions and share anticipated challenges, the second training session included feedback from the staff involved in the pilot trial where they shared their experiences and questions based on the pilot. This feedback also led to enhancements to the study materials, for example, development of a standardized script for counseling caregivers following a positive screen. Following these training sessions, throughout the study period, there was a chat-group set up via a mobile phone application that was commonly used in the study setting. This group included the lead nurses in each site and the study investigators and provided an avenue for sharing of questions and issues if any, to which the study team could respond promptly and appropriately.

The study was supported by research staff whose primary roles were to consent eligible families, coordinate appointments for diagnostic evaluations for screen positive patients, follow-up selected screen negative patients, and to do data entry for the study sample. The clinics thus functioned independently in terms of administration of the screening tool. A feasibility questionnaire (Supplemental Material 2) was administered to all primary care nurses and physicians while the study was ongoing (i.e. 18 months after initiation of study). This questionnaire contained questions on acceptability, practicality, and efficacy of the tool given the current clinic infrastructures and staff training, the time needed for administration, and its potential for scalability. Responses were in the form of a Likert-type scale with options including strongly agree, mildly agree, mildly disagree, and strongly disagree. Acceptable feasibility was defined as having ⩾70% of respondents rating all items as mildly or strongly agree. This feasibility questionnaire was readministered when the M-CHAT-R/F was adopted as a part of the standard clinical workflow (i.e. after study completion and when there was no longer any research staff support)—this was only to nurses as the screening process primarily involved the nurses under the standard clinical workflow

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using Stata MP 17 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Exploratory data analyses were performed with the Mann–Whitney test and Chi-square test. The predictive accuracies, sensitivity, and specificity of the M-CHAT-R/F screening tool were presented. An estimate of sensitivity and specificity was calculated based on the subgroup of randomly selected children who were screened negative and underwent diagnostic evaluations. The confirmatory analysis concerning M-CHAT-R/F screening was conducted with the linear mixed model (Hardin et al., 2007) with an underlying binomial distribution and logit link, in view of the multicenter data structure. However, the two-level data (i. individual, ii. centers) could be collapsed into a single level and analyzed with the binary logistic regression if the intraclass correlation (ICC) was below the threshold of 0.1. The model was refined with two-machine learning variable-selection procedure, namely, classification and regression (CART) and Elastic Net. The Firth logistic regression (Firth, 1993) could be applied if positive M-CHAT-R/F was a rare event (say below 3%). The results of the feasibility questionnaire were analyzed with the two-sample Fisher’s exact test. All statistical analyses were carried out with a 5% level of significance and the equivalent 95% confidence intervals.

Sample size calculation was based on reported global autism prevalence of 1% and to allow identification of at least 50 children on the autism spectrum. We hence aimed to screen at least 5000 children across the seven primary care clinic sites and anticipated that the expected number of children who screened positive after the two-stage M-CHAT-R/F screening and require follow-up evaluation would be 110. This would ensure that the statistical power could exceed 95% in view of the proposed data analysis and the data structures involved.

Results

The final study sample comprised 5336 children (51.3% male gender) with a mean age of 18.6 months (SD 0.9). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample. The sample was consistent with the ethnic profile of the country (64.2% Chinese, 23.9% Malay, 5.8% Indian, and 6.2% other groups or mixed heritage). More than half (61.1%) of the children were not enrolled in a preschool or similar facility, while 33.1% were enrolled in a full-day program at a preschool and 5.8% in half-day or shorter programs. The vast majority (97.2%) of respondents were parents and there were wide variations in maternal and paternal highest levels of education and household income. A small minority (6.9%) identified themselves as receiving some form of financial assistance for any of the family’s needs and would be considered to be of low socioeconomic status. In terms of family history, 2.1% of the sample had a sibling on the autism spectrum.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of sample (N = 5336 children).

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Child-level characteristics | |

| Male gender | 2738 (51.3%) |

| Race | |

| Chinese | 3423 (64.2%) |

| Malay | 1277 (23.9%) |

| Indian | 308 (5.8%) |

| Other | 328 (6.2%) |

| Preschool enrolment | |

| Not in school | 3244 (60.8%) |

| Full-day | 1760 (33.0%) |

| Half-day (or less) | 308 (5.8%) |

| Missing | 24 (0.4%) |

| Main caregiver | |

| Mother | 3167 (59.4%) |

| Father | 190 (3.6%) |

| Grandparent | 1202 (22.5%) |

| Family’s domestic helper a | 617 (11.6%) |

| Others | 134 (2.5%) |

| Missing | 26 (0.5%) |

| Presence of chronic medical condition b | 196 (3.7%) |

| Term gestation | 4614 (86.5%) |

| Number of siblings | |

| 0 | 2401 (45.0%) |

| 1 | 1783 (33.4%) |

| 2 | 641 (12.0%) |

| ⩾3 Missing |

238 (4.5%) 273 (5.1%) |

| Has a sibling on the autism spectrum | 109 (2.0%) |

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age in months | 18.6 (0.9) |

| Weighted screen time (h/day) | 1.3 ± 1.3 |

| Respondent/family level characteristics, N (%) | |

| Person who completed the study questionnaires | |

| Mother |

3533 (66.2%) |

| Father | 1653 (31.0%) |

| Grandparent | 40 (0.7%) |

| Others | 6 (0.1%) |

| Missing | 104 (1.9%) |

| Marital status of parents | |

| Single | 51 (1.0%) |

| Married | 5126 (96.1%) |

| Widowed | 7 (0.1%) |

| Divorced/separated | 42 (0.8%) |

| Missing | 110 (2.1%) |

| Mother’s education level | |

| High-school or below | 956 (17.9%) |

| Diploma | 1145 (21.5%) |

| Graduate or above | 3098 (58.1%) |

| Others | 11 (0.2%) |

| Missing | 126 (2.4%) |

| Father’s education level | |

| High-school or below | 1271 (23.8%) |

| Diploma | 1112 (20.8%) |

| University or above | 2796 (52.3%) |

| Others | 13 (0.2%) |

| Missing | 144 (2.7%) |

| Respondent concerns for autism | 592 (11.1%) |

| Household income | |

| <US$2000 | 185 (3.5%) |

| US$2000–US$4000 | 841 (15.8%) |

| US$4001–US$6000 | 978 (18.3%) |

| US$6001–US$8000 | 978 (18.3%) |

| >US$8000 | 2216 (41.5%) |

| Missing | 138 (2.6%) |

| Family receiving financial subsidies | 361 (6.8%) |

Foreign domestic helper is a common phenomenon in Singapore, whereby a family has a permanent live-in helper who is employed specifically to assist with childcare and/or family household chores and stays with the family on a contract basis, typically for 2 years at a time.

Chronic medical disease—refers to any condition necessitating daily intake of medications and regular follow-up with a physician. Examples include asthma, childhood eczema, and allergic rhinitis.

Initial screening results

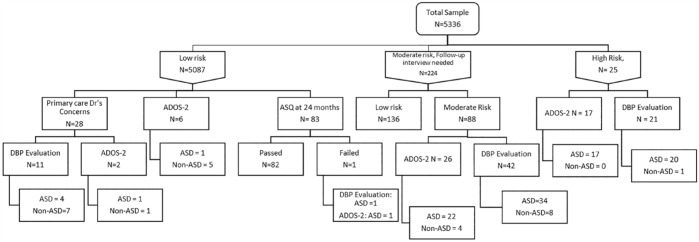

The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. All patients completed the screening with the M-CHAT-R/F fully, including the second stage follow-up interview where indicated. The vast majority of the sample (N = 5087, 95.3%) were low risk and screened negative on the M-CHAT-R/F. Within this group, 28 children were assessed by the primary care physician to have concerns for autism and offered further diagnostic evaluation. From the entire sample, 25 children (0.5%) were classified as high risk following the M-CHAT-R/F initial screen, while 224 (4.2%) were classified as medium risk and received the follow-up interview; subsequently 88 (1.6% of the entire sample) were screened positive. Hence in all, 113 children (2.1%) attained a screen positive status on the M-CHAT-R/F and were eligible for further diagnostic evaluation.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

*Note: Numbers of study participants who declined follow-up evaluations under each arm are not shown in this figure, to ensure readability. ADOS-2: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – 2nd edition, DBP: Developmental Behavioral Pediatrician, ASQ: Ages and Stages Questionnaire, ASD: autism spectrum disorder.

Diagnostic evaluations

Figure 1 shows the outcome of evaluations of positively screened children. The majority (21 out of 25) of high-risk children attended the CDU for further evaluations and 20 met the criteria for autism following DBP evaluation. One child was diagnosed with isolated language delay. In this same group of high-risk children, 17 underwent the ADOS-2 and all were classified as autism. Among children in the medium-risk group, 42 (47.7%) attended further evaluation with 34 meeting criteria for autism following DBP evaluation. Seven were diagnosed to have isolated language delay or global developmental delay. The remaining child did not meet criteria for any developmental condition. Among 26 medium-risk children who had an ADOS-2, the majority (N = 22, 84.6%) were classified as autism. In all, 54 (47.8%) children who had a positive screen on the M-CHAT-R/F were diagnosed with autism. Comparing the group of children who were screened positive and attended follow-up evaluations with the group who did not, those who attended were more likely to be male and have parental concerns for autism. No other demographic differences were found between the two groups. The predominant reasons for declining follow-up evaluations were that the caregiver either felt that their child did not have autism or that they were too young to undergo further developmental evaluations or both.

Negative screens

A random sample of 83 children with negative screens were followed-up 6 months after the initial M-CHAT-R/F screening and parents were asked to complete the Communication domain of the ASQ (Figure 1). All the children except one passed this screen. The one child who scored below the cut-off underwent further evaluation at the CDU and received a diagnosis of autism by the DBP and by the psychologist on the ADOS. A separate subset of 15 children with a negative screen were also offered an ADOS at the CDU. Out of this, six children completed the assessment with five not meeting the autism criteria, while one met the criteria.

Separately, 11 out of 28 children who had a negative screen in the initial M-CHAT-R/F but for whom the primary care physician had concerns for autism attended further evaluation. The majority in this group (N = 7) had a diagnosis of isolated language delay following DBP evaluation with four meeting the DSM-5 criteria for autism.

Psychometric properties of the M-CHAT-R/F

Performance of the M-CHAT-R/F was analyzed using the two parts of the diagnostic evaluation employed in the study, that is, DBP evaluation and psychologist evaluation incorporating the ADOS-2. Based on results of the DBP evaluations (i.e. diagnosis of autism by the DBP; Table 2), the PPV of the M-CHAT-R/F was 85.7% (54/63), sensitivity was 81.8% (54/66), specificity was 55.0% (11/20), and NPV was 47.8% (11/23). The accuracy rate of the M-CHAT-R/F was 75.6%, that is, the M-CHAT-R/F screening result corresponded to the DBP evaluation result 75.6% of the time. Based on results incorporating the ADOS-2 evaluation, the performance of the M-CHAT-R/F was better with higher PPV (90.7%, 39/43), sensitivity (88.6%, 39/44), specificity (71.4%, 10/14), and NPV (66.7%, 10/15). The use of the ADOS-2 is the more well-studied, standardized, and robust evaluation method for an autism diagnosis, thereby lending greater weight to the psychometric properties as calculated based on the ADOS-T results. Examining the PPV for the presence of any developmental disorder showed a high PPV of 98.4%. Sensitivity analysis after removal of participants with a positive M-CHAT-R/F screen and a sibling on the autism spectrum (N = 8) did not alter the derived psychometric properties of the M-CHAT-R/F with a PPV of 88.9%, sensitivity 88.9%, specificity 71.4%, and NPV 71.4% based on ADOS-2 evaluation.

Table 2.

Psychometric properties of M-CHAT-R/F.

| Property | Using DBP evaluation (%) | Using ADOS evaluation (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 81.8 | 88.6 |

| Specificity | 55.0 | 71.4 |

| Positive predictive value | 85.7 | 90.7 |

| Negative predictive value | 47.8 | 66.7 |

| Diagnostic accuracy | 75.6 | 84.5 |

M-CHAT-R/F: Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up; DBP: developmental–behavioral pediatrician; ADOS: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule.

Predictors of a positive screen

The results of the Firth logistic regression on predictors of a positive M-CHAT-R/F screen are presented in Table 3. The models were estimated in view of the low incidence of positive cases (113/5336 or 2.2%). Children with a higher initial M-CHAT-R/F score, concerns from a primary care physician for autism, whose parents were concerned about autism, had other children diagnosed with autism, of male gender, and in need of financial subsidies, all had higher odds of being screened positive. Compared with other ethnicities, Malay children also had higher odds of being screened positive. In contrast, children who attended full-day preschool or childcare, who were born within 3 weeks of expected due date, with either parent with an educational level of university degree of higher, and with a household income of at least SG$ 4000 (the median value for the nation; US$ 1 = SG$ 1.36), were less likely to be screened positive.

Table 3.

Factors associated with a positive M-CHAT-R/F screen.

| Unadjusted odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio a | Adjusted odds ratio b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M-CHAT-R/F pre-score | 4.51* | 3.31 (2.62−4.18)* | |

| M-CHAT-R/F pre-score >3 | 70.78 (32.04−156.37)* | ||

| Primary care physician concerns for autism | 751.77 (405.39−1394.10)* |

61.73 (27.53−138.44) | 185.92 (88.65−389.93) |

| Male gender | 0.49* | 0.4 (0.37−1.88) | |

| Age (months) | 1.07 | ||

| Race | |||

| Chinese | Reference | ||

| Malay | 2.23* | ||

| Indian | 0.19 | ||

| Other | 0.88 | ||

| School attendance | |||

| Not in school | Reference | Reference | |

| Full-day | 0.61* | 1.01 (0.43−2.40) | |

| Half day (or less) | 0.51 | 0.13 (0.02−0.99)* | |

| Term gestation | 0.62* | ||

| Presence of chronic medical condition | 1.21 | ||

| Has a sibling on the autism spectrum | 4.95* | ||

| Weighted screen time (h/day) | 1.48 | ||

| Mother’s education | |||

| Primary school or below | Reference | ||

| High school | 0.49 | ||

| Diploma | 0.17* | ||

| University | 0.12* | ||

| Other | 3.56* | ||

| Father’s education | |||

| Primary school or below | Reference | ||

| High school | 0.79 | ||

| Diploma | 0.46 | ||

| University | 0.24* | ||

| Household income | |||

| <US$2000 | Reference | Reference | |

| US$2000–US$4000 | 0.74 | 3.20 (0.69−14.81) | |

| US$4001–US$6000 | 0.22* | 1.36 (0.28−6.60) | |

| US$6001–US$8000 | 0.30* | 1.88 (0.37−9.59) | |

| >US$8000 | 0.14* | 1.39 (0.29−6.56) | |

| Family receiving financial subsidies | 3.22* | ||

| Respondent concerns for autism | 5.34* | ||

M-CHAT-R/F: Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up.

Identified with elastic net.

Identified with CART.

p < 0.05

The above bivariate analyses were enhanced in the context of multivariable models. First, the elastic net algorithm identified school attendance, household income, initial M-CHAT-R/F score, and primary care physician concerns as joint predictors. Second, the CART algorithm further identified the optimum cut-point for the initial M-CHAT-R/F score. The results were consolidated with these algorithms. Children whose initial M-CHAT-R/F score was above 3 and had concerns from primary care physician for autism were more likely to be screened positive. The other significant predictors identified in the exploratory analyses were dominated by these two variables.

Feasibility of screening

Healthcare professionals involved in the study were asked to complete a feasibility questionnaire in two rounds. The first round was conducted 18 months post-initiation of the study and while the study was ongoing (Round 1); 47 nurses and 26 physicians responded. The second round was conducted 26 months post-initiation of study after study completion and during clinical implementation (Round 2) and was targeted at nurses; 51 nurses completed the questionnaire. During Round 2, there were no research staff supporting the screening processes. In both rounds, participation was invited from professionals across all seven clinic sites and the distribution of respondents in terms of clinic site was similar. The respondents in each round were also identical, that is, the same set of nurses across the clinic sites were sampled in both rounds (apart from natural turnover within the real-world setting) and all respondents had administered and used the M-CHAT-R/F for screening. Overall, the majority of respondents (ranging from 71% to 98%), agreed on the acceptability and efficacy of the M-CHAT-R/F as a screening tool in both rounds (Table 4). Table 4 also shows the responses from nursing staff alone in Round 1. Two statements on practicality were agreed with by less than half of the nursing staff in Round 1; specifically, those regarding the time taken for screening and balancing this with respect to other clinical responsibilities. However, this improved in Round 2 (without requirement for study-related consent taking) such that 78.3% were in agreement with the practicality of use. Comparing responses between Round 1 (nursing staff only) and Round 2, there was a significant increase in the proportion of respondents who were in agreement of the two practicality statements and one acceptability statement.

Table 4.

Feasibility study of screening with the M-CHAT-R/F.

| Question | Round 1 (entire sample) a | Round 1n (nursing staff only) a | Round 2 (nursing staff) a | p-value b | p-value c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | |||||

| 1. I feel positive about the M-CHAT-R/F being used routinely in our clinics | 63/73 (86%) | 41/47 (87%) | 50/51 (98%) | 0.044** | 0.026** |

| 2. I had to answer queries from caregivers regarding the M-CHAT- R/F questionnaire questions | 53/73 (72%) | 43/47 (92%) | 45/51 (88%) | 0.424 | 0.044** |

| 3. I had adequate preparatory training in using the M-CHAT-R/F | 52/73 (71%) | 40/47 (85%) | 44/51 (86%) | 0.548 | 0.053 |

| 4. I felt equipped to answer questions and clarifications from caregivers | 56/73 (76%) | 36/47 (77%) | 43/51 (84%) | 0.239 | 0.366 |

| 5. I believe that I have gained some knowledge following the use of the M-CHAT-R/F | 64/73 (88%) | 43/47 (92%) | 48/51 (94%) | 0.454 | 0.356 |

| Practicality | |||||

| 1. The time taken for the M-CHAT-R/F is acceptable | 41/73 (56%) | 22/47 (47%) | 41/51 (80%) | 0.001** | 0.007** |

| 2. I had enough time to do my other standard clinical duties | 40/73 (55%) | 20/47 (43%) | 35/51 (69%) | 0.008** | 0.138 |

| 3. The questions and the format of the M-CHAT-R/F do not need any change and can be used in the current format | 58/73 (79%) | 34/47 (72%) | 44/51 (86%) | 0.072 | 0.353 |

| Efficacy | |||||

| 1. I think the M-CHAT-R/F is a good screening tool to be used in Singapore primary care clinics | 66/73 (90%) | 42/47 (89%) | 50/51 (98%) | 0.085 | 0.139 |

| 2. Having the results of the M-CHAT-R/F will help in my clinical decision making for children | 65/73 (89%) | 42/47 (89%) | 46/51 (90%) | 0.576 | 0.999 |

| 3. I believe that using this tool will help improve our care for children | 64/73 (88%) | 41/47 (87%) | 49/51 (96%) | 0.109 | 0.123 |

M-CHAT-R/F: Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up.

Proportion of participants who agreed or strongly agreed with the statement.

p-value comparing proportions in Round 1 (nursing staff only) against Round 2.

p-value comparing proportions in Round 1 (entire sample) against Round 2.

Statistically significant at 5%.

Discussion

Our results indicate high sensitivity, specificity, and PPV of the M-CHAT-R/F as a screening instrument for autism. These results were derived within a study conducted across seven primary care clinics in Singapore, where healthcare professionals reported high feasibility of the screening tool implementation. As such, we demonstrate validity and feasibility of M-CHAT-R/F in systematically screening for autism at a population level within primary care clinics in an Asian country. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the use of the M-CHAT-R/F among well children and associated rates of autism incidence in Singapore.

Initial screening results indicated that 4.2% of the sample required a follow-up interview. This is lower than that reported in samples from the United States (Robins et al., 2014) (7.2%), Turkey (Oner & Munir, 2020) (9.7%), China (Guo et al., 2019) (14.4%), and Albania (Brennan et al., 2016) (9.8%) but comparable to a study in Iceland (Jonsdottir et al., 2022) (4.0%). Of note, all of these other studies included children across a wider age group, including 30 or 36 months of age while our sample comprised toddlers approximately 18 months of age. Cultural differences in interpretation of questions have been shown to lead to differences in endorsement of questions across international samples in a previous study (Stevanovic et al., 2022). This and age-related applicability of questions likely contributed to this difference. Regardless, this indicates that the vast majority of children will screen negative and will not need a follow-up interview from primary care healthcare professionals. Our final positive screen rates following the interview (2.1%) were comparable with the aforementioned studies and indicate the proportion that would need further evaluations after M-CHAT-R/F; this is important for resource-planning and diagnostic capabilities. Participants who eventually met criteria for autism was 1.1% which was also similar to the global median prevalence and suggest acceptable external validity of our study in terms of case-identification. Interestingly, this rate was slightly higher than that reported in the early validation studies (Brennan et al., 2016; Robins et al., 2014) but comparable to more recent studies, including one from Asia (Guo et al., 2019; Magan-Maganto et al., 2020). The temporal increase in autism prevalence over time likely contributed to this observation.

Consistent with other studies across various continents, the performance of the M-CHAT-R/F as a screening tool for autism in Singapore was acceptable with a high sensitivity of 88.6% (Guo et al., 2019; Magan-Maganto et al., 2020; Oner & Munir, 2020; Wieckowski et al., 2021). This sensitivity value was above the threshold of 70.0% recommended by the AAP to be considered as an effective screening tool (Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, & Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee, 2006). The derived PPV for autism was also very high, which was likely an overestimate given that a substantial proportion (44.2%) of children with a positive screen did not attend the diagnostic evaluation. Many in this group might be false-positives and would not have met the criteria for a diagnosis of autism. Nonetheless, even after accounting for a possible lowering of the PPV, our results support the use of the M-CHAT-R/F for screening. The PPV for the presence of any developmental disorder remained very high at 98.4%. Our specificity of 71.4% and NPV 66.7% appeared lower than the initial validation study (Robins et al., 2014). In this study, we did not assume that negatively screened children without a diagnostic evaluation were true-negatives and we based our calculations only on those children with a diagnostic evaluation. This could have underestimated the NPV. Nonetheless, given the nature of autism whereby social communication difficulties could become more pronounced after 18 months of age, the false-negative cases were reasonable. We also employed rigorous attempts to detect false-negative cases with intentional evaluations of children with a negative screen, which likely contributed to the lower NPV. Our findings support the role of repeated screening in later childhood after the initial 18-month screen and the need for long-term follow-up of children after screening in a prospective manner to allow for better detection of true- and false-positive screening results.

In terms of predictors of a positive screen, the final predictors of primary care physician concerns for autism and a higher pre-interview score on the M-CHAT-R/F were not surprising and suggest a complementary role for primary care physician evaluation to systematic screening. However, parental concerns for autism, need for financial subsidies, and male gender were all associated with higher odds of a positive screen in the initial regression model. Although these were not significant after multivariable adjustment, they could have clinical implications in terms of factors that may increase a child’s likelihood of having a positive screen. Indeed, a recent previous study also showed that males were at a higher likelihood of having a positive final M-CHAT-R/F screen as compared with females, even though the sensitivity of the M-CHAT-R/F in that study did not differ based on gender (Eldeeb et al., 2023). This difference may be related to both differences in the endophenotype of autism between males and females, as well as the overall higher prevalence of autism among males as compared with females based on current data. While we did not examine psychometric properties based on gender in this study, future studies will explore possible gender differences further.

In Singapore, the primary care screening is predominantly completed by primary care physicians with varying clinical experience in pediatrics and child development. In addition, a previous study done in Singapore has shown that completion rates of the current developmental checklists in the health booklet by parents were low (Koh et al., 2016), supporting the argument to have a standardized screening tool for autism to complement the clinical evaluation. Hence, the feasibility of implementation is critical, in order to incorporate systematic screening as a part of routine clinical care. Our study adds to the existent literature by demonstrating high feasibility of incorporating M-CHAT-R/F into the routine clinical workflow of primary care clinics in Singapore. The low requirements for follow-up interviews, ease of administration, and minimal training of staff may be easily scalable across the country. The M-CHAT-R/F is also available in multiple languages, including in Mandarin and Malay, which is relevant in the multiethnic population of Singapore. Although the study coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare professionals rated this screening tool with high acceptability. By assessing feasibility twice, including during and after the study, we demonstrate improvements in scores over time, which likely reflects healthcare professionals, especially nursing staff becoming more familiar and confident with the screening tool. Presence of the standardized screening using the M-CHAT-R/F also worked independently of the clinical evaluation during the well-child visit by the primary care physician—13.3% of children who screened positive on the M-CHAT-R/F did not have any concerns for autism reported by the physician and would not have been referred for further evaluation without the screening results. All these children eventually had some form of developmental disorder with 33.3% having autism. Hence the screening contributed to the routine clinical evaluation by the primary care physician to identify children with early features of autism. Nonetheless, it is critical to continue the routine well-child visit by primary care physicians, as the presence of physician concerns for autism is a consistent predictor of a positive screen on the M-CHAT-R/F in this study. Caregivers who bring children to the primary care clinic may not always be the primary caregiver or a parent; hence, the M-CHAT-R/F may be less reliable in these cases and a clinical evaluation by the primary care physician may be a more objective assessment.

Prior to 2020, autism-specific developmental screening was not routinely implemented in primary care clinics in Singapore. In a retrospective study examining autism trends in Singapore in 2016–2018 (Aishworiya et al., 2021), the mean age at autism diagnosis was 35.5 months, and age of receiving intervention was 42.0 months. In this study, children who screened positive were seen for a comprehensive evaluation by a mean age of 21.9 months and began autism-specific therapy at a mean age of 22.1 months. Continued involvement of the research team in following the original cohort of children and recruiting new samples will better clarify whether detection rates of autism have improved and age of autism diagnosis has been lowered. This information will inform policymakers and facilitate a discussion of incorporating autism screening across all polyclinics nationwide.

Strengths of this study include first, the large sample size with all children completing the recommended two-stage screening process with no incomplete screens. A common problem seen in previous studies pertains to the number of incomplete screens (up to 49%) due to loss of follow-up of children (Bradbury et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2019). This study is different in that the research administration of M-CHAT-R/F has been designed into the primary clinic workflow from study conception and involves staff from the entire clinic, with follow-up interviews administered immediately after the initial screening. Second, we intentionally incorporated results of the standard clinical evaluation by the primary care physician, regardless of the results on the M-CHAT-R/F, to increase detection of false-negative screens. Third, employment of three different methods to detect false-negative screens (independent primary care physician’s evaluation, ASQ, and ADOS-2 administration) also increases the reliability of our derived results.

Our study is not without limitations. First, there was a significant proportion of children with a positive screen who did not attend follow-up evaluations. This limitation is not unique to our study (Robins et al., 2014; Wieckowski et al., 2021) and could be related to the cultural stigma associated with autism within Singapore (Goh et al., 2021). Future studies will explore alternative modes for follow-up evaluation (e.g. telemedicine) to examine whether this improves the follow-up rate. Second, we did not exclude participants who were born premature or who had siblings on the autism spectrum to keep a broad inclusion criterion. However, this information was collected and results were not significantly different after removal of children with a sibling on the autism spectrum. Furthermore, our study included minimal children with a history of prematurity, as these children are typically managed at tertiary pediatric centers for their well-child care in Singapore. Finally, we limited use of the M-CHAT-R/F to the English version only, thereby potentially excluding caregivers who were not proficient in the language. This is likely to be only a small proportion given the high English literacy rates (80.0%) among adults in the country (Department of Statistics, 2010).

Future studies will examine the stability of screen status beyond 18 months to better understand the role of repeated screening and whether M-CHAT-R/F shows different psychometric properties in older children up to 30 months. Further studies will also examine the outcomes of children who started autism-specific therapies earlier after screening at 18 months. Qualitative studies investigating the perceptions of caregivers using a transtheoretical model of behavior change and reasons for delaying diagnostic evaluations would allow clinicians and researchers alike to identify strategies in enhancing adherence to recommendations after screening.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the validity of the M-CHAT-R/F as a screening instrument for autism within a primary care clinic setting. The implementation of this screening tool is reported as highly feasible by healthcare professionals in Singapore. With the use of historical cohorts, this study suggests that systematic screening may reduce the age at autism diagnosis and facilitate earlier initiation of autism-specific intervention, which has the potential of bringing about positive changes to health, social, and economic outcomes related to autism at a population level.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-aut-10.1177_13623613231205748 for Validity and feasibility of using the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F) in primary care clinics in Singapore by Ruth Mingli Zheng, Siew Pang Chan, Evelyn C Law, Shang Chee Chong and Ramkumar Aishworiya in Autism

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-aut-10.1177_13623613231205748 for Validity and feasibility of using the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F) in primary care clinics in Singapore by Ruth Mingli Zheng, Siew Pang Chan, Evelyn C Law, Shang Chee Chong and Ramkumar Aishworiya in Autism

Acknowledgments

The study team acknowledges and extends their appreciation to the following team members for their contributions in this study. Administrative support: Chang Yang Yi, Marc Amiruddin Nabill Bin Abdul Malek, Kang Ying Qi, Naeem Sani, Jane Sum Mei Jun, Tran Anh Phuong, and Matthew Chua. Mentorship support: Meena Sundram and Victor Loh Weng Keong. Nursing personnel support: Jancy Mathews, Mabel Ong, Seah Hui Min, Ong Li Ping, Li Junru, Vasantha Supramaniam, Emmeline Gianan Pua, Sow Hooi Ching, Farhana Abu Bakar, and Li Mingzhu. Psychologist support for diagnostic assessment administration: Ong Goon Tat, Cheryl Huiling Ong and Elizabeth Sarah Ragen. They also thank Howard Bauchner, MD, for critically reviewing the manuscript before submission.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by grants from the NUHS Primary Care Physician Research Development Seed Grant (NUHSRO/2020/034/RO5+5/PCPRD-Oct19/1) and the Octava Foundation Grant.

Ethical consideration: The study was approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Research Board (NHG DSRB Ref: 2019/00689)). Parents/legal guardians of eligible children provided written consent.

ORCID iD: Ramkumar Aishworiya  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5749-1248

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5749-1248

Access to data and data sharing: The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Aishworiya R., Goh T. J., Sung M., Tay S. K. H. (2021) Correlates of adaptive skills in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 25(6), 1592–1600. 10.1177/1362361321997287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aishworiya R. M. V., Stewart S., Hagerman R., Feldman H. (2023). Meta-analysis of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised/Follow-Up for screening. Pediatrics, 151(6), Article e2022059393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury K., Robins D. L., Barton M., Ibanez L. V., Stone W. L., Warren Z. E., Fein D. (2020). Screening for autism spectrum disorder in high-risk younger siblings. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 41(8), 596–604. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan L., Fein D., Como A., Rathwell I. C., Chen C. M. (2016). Use of the Modified Checklist for Autism, revised with follow up: Albanian to screen for ASD in Albania. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(11), 3392–3407. 10.1007/s10803-016-2875-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher A. V., Cidav Z., Knapp M., Mandell D. S. (2014). Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, 168(8), 721–728. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone P. S., Campbell K., Wilkes J., Stoddard G. J., Huynh K., Young P. C., Gabrielsen T. P. (2020). Primary care autism screening and later autism diagnosis. Pediatrics, 146(2), Article e20192314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, & Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. (2006). Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: An algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics, 118(1), 405–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics (2010). Census of Population 2010 Statistical Release 1: Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion, Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry, Republic of Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Eldeeb S. Y., Ludwig N. N., Wieckowski A. T., Dieckhaus M. F., Algur Y., Ryan V., Dufek S., Stahmer A., Robins D. L. (2023). Sex differences in early autism screening using the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised, with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F). Autism, 27, 2112–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology & Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health Singapore. (2010). Singapore burden of disease study 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Firth D. (1993). Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika, 80(1), 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller E. A., Oliver K., Vejnoska S. F., Rogers S. J. (2020). The effects of the early start Denver model for children with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Brain Science, 10(6), Article 368. 10.3390/brainsci10060368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh J. X., Aishworiya R., Ho R. C. M., Wang W., He H. G. (2021). A qualitative study exploring experiences and support needs of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in Singapore. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(21–22), 3268–3280. 10.1111/jocn.15836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C., Luo M., Wang X., Huang S., Meng Z., Shao J., Zhang X., Shao Z., Wu J., Robins D. L., Jing J. (2019). Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised, with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(1), 185–196. 10.1007/s10803-018-3682-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie W., Wallis K., Bennett A., Brooks E., Dudley J., Gerdes M., Pandey J., Levy S. E., Schultz R. T., Miller J. S. (2019). Accuracy of autism screening in a large pediatric network. Pediatrics, 144(4), Article e20183963. 10.1542/peds.2018-3963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin J. W., Hardin J. W., Hilbe J. M., Hilbe J. (2007). Generalized linear models and extensions. Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hong J. S., Singh V., Kalb L., Ashkar A., Landa R. (2021). Replication study of ADOS-2 Toddler Module cut-off scores for autism spectrum disorder classification. Autism Research, 14(6), 1284–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman S. L., Levy S. E., Myers S. M. (2020). Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics, 145(1), Article e20193447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsdottir S. L., Saemundsen E., Jonsson B. G., Rafnsson V. (2022). Validation of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-up in a population sample of 30-month-old children in Iceland: A prospective approach. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(4), 1507–1522. 10.1007/s10803-021-05053-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khowaja M. K., Hazzard A. P., Robins D. L. (2015). Sociodemographic barriers to early detection of autism: Screening and evaluation using the M-CHAT, M-CHAT-R, and follow-up. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(6), 1797–1808. 10.1007/s10803-014-2339-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh H. C., Ang S. K. T., Kwok J., Tang H. N., Wong C. M., Daniel L. M., Goh W. (2016). The utility of developmental checklists in parent-held health records in Singapore. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 37(8), 647–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo A. A., Etzel R. A., Chilton L. A., Watson C., Gorski P. A. (2012). Primary care pediatrics and public health: Meeting the needs of today’s children. American Journal of Public Health, 102(12), e17–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. S., Chung S. J., Thomas H. R., Park J., Kim S. H. (2019). Exploring diagnostic validity of the autism diagnostic observation schedule-2 in south Korean toddlers and preschoolers. Autism Research, 12(9), 1356–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H., Chan T., Yoong T. (1994). Denver developmental screening test (DDST). Singapore Medical Journal, 35, 156–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C., Rutter M., DiLavore P., Risi S., Gotham K., Bishop S. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule Second Edition (ADOS-2) Manual (Part 1): Modules 1–4. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Luyster R., Gotham K., Guthrie W., Coffing M., Petrak R., Pierce K., Bishop S., Esler A., Hus V., Oti R. (2009). The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Toddler Module: A new module of a standardized diagnostic measure for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1305–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magan-Maganto M., Canal-Bedia R., Hernandez-Fabian A., Bejarano-Martin A., Fernandez-Alvarez C. J., Martinez-Velarte M., Martin-Cilleros M. V., Flores-Robaina N., Roeyers H., Posada de la Paz M. (2020). Spanish cultural validation of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(7), 2412–2423. 10.1007/s10803-018-3777-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzouri L., Yousefian S., Keshtkari A., Hashemi N. (2019). Advanced Parental Age and Risk of Positive Autism Spectrum Disorders Screening. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10, Article 135. 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_25_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow M., Servili C., Tomlinson M. (2019). A review of screening tools for the identification of autism spectrum disorders and developmental delay in infants and young children: Recommendations for use in low-and middle-income countries. Autism Research, 12(2), 176–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie K., Forsyth K., O’Hare A., McClure I., Rutherford M., Murray A., Irvine L. (2015). Factors influencing waiting times for diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in children and adults. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 45, 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner O., Munir K. M. (2020). Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers Revised (MCHAT-R/F) in an urban metropolitan sample of young children in Turkey. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(9), 3312–3319. 10.1007/s10803-019-04160-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phua H., Chua A., Ma S., Heng D., Chew S. (2009). Singapore’s burden of disease and injury. Singapore Medical Journal, 50(5), 468–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K., Gazestani V. H., Bacon E., Barnes C. C., Cha D., Nalabolu S., Lopez L., Moore A., Pence-Stophaeros S., Courchesne E. (2019). Evaluation of the diagnostic stability of the early autism spectrum disorder phenotype in the general population starting at 12 months. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, 173(6), 578–587. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins D. L., Casagrande K., Barton M., Chen C.-M. A., Dumont-Mathieu T., Fein D. (2014). Validation of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, revised with follow-up (M-CHAT-R/F). Pediatrics, 133(1), 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S. J., Estes A., Lord C., Munson J., Rocha M., Winter J., Greenson J., Colombi C., Dawson G., Vismara L. A., Sugar C. A., Hellemann G., Whelan F., Talbott M. (2019). A multisite randomized controlled two-phase trial of the early start Denver model compared to treatment as usual. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(9), 853–865. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogge N., Janssen J. (2019). The economic costs of autism spectrum disorder: A literature review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(7), 2873–2900. 10.1007/s10803-019-04014-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-García A. B., Galindo-Villardón P., Nieto-Librero A. B., Martín-Rodero H., Robins D. L. (2019). Toddler screening for autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 1837–1852. 10.1007/s10803-018-03865-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires J., Bricker D. D., Twombly E. (2009). Ages & stages questionnaires. Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Stevanovic D., Robins D. L., Costanzo F., Fuca E., Valeri G., Vicari S., Erkuran H. O., Yaylaci F., Albores-Gallo L., Gatica-Bahamonde G., Gabunia M., Zirakashvili M., Charman T., Samadi S. A., Toh T.-H., Gayle W., Brennan L., Zorcec T., Auza A. . ., Knez R. (2022). Cross-cultural similarities and differences in reporting autistic symptoms in toddlers: A study synthesizing M-CHAT (-R) data from ten countries. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 95, Article 101984. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J. M., Lu L., Jeng S. F., Cheong P. L., Gau S. S., Huang Y. H., Wu Y. T. (2019). Feb). Validation of the modified checklist for autism in toddlers, revised with follow-up in Taiwanese toddlers. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 85, 205–216. 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velikonja T., Edbrooke-Childs J., Calderon A., Sleed M., Brown A., Deighton J. (2017). The psychometric properties of the Ages & Stages Questionnaires for ages 2-2.5: A systematic review. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43(1), 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis K. E., Guthrie W. (2020). Identifying autism spectrum disorder in real-world health care settings. Pediatrics, 146(2), Article e20201467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieckowski A. T., Hamner T., Nanovic S., Porto K. S., Coulter K. L., Eldeeb S. Y., Chen C. A., Fein D. A., Barton M. L., Adamson L. B., Robins D. L. (2021). Early and repeated screening detects autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Pediatrics, 234, 227–235. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieckowski A. T., Williams L. N., Rando J., Lyall K., Robins D. L. (2023). Sensitivity and specificity of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (original and revised): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, 177, 373–383. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan J., Fombonne E., Scorah J., Ibrahim A., Durkin M. S., Saxena S., Yusuf A., Shih A., Elsabbagh M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. 10.1002/aur.2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Luo Y., Zhang R., Zheng X. (2023). Direct and indirect costs for families of children with autism spectrum disorder in China. Autism. Advance online publication. 10.1177/13623613231158862 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zwaigenbaum L., Bryson S. E., Brian J., Smith I. M., Roberts W., Szatmari P., Roncadin C., Garon N., & Vaillancourt T. (2016). Stability of diagnostic assessment for autism spectrum disorder between 18 and 36 months in a high-risk cohort. Autism Research, 9(7), 790–800. 10.1002/aur.1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-aut-10.1177_13623613231205748 for Validity and feasibility of using the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F) in primary care clinics in Singapore by Ruth Mingli Zheng, Siew Pang Chan, Evelyn C Law, Shang Chee Chong and Ramkumar Aishworiya in Autism

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-aut-10.1177_13623613231205748 for Validity and feasibility of using the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F) in primary care clinics in Singapore by Ruth Mingli Zheng, Siew Pang Chan, Evelyn C Law, Shang Chee Chong and Ramkumar Aishworiya in Autism