Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, resulting in motor dysfunction. Current treatments are primarily centered around enhancing dopamine signaling or providing dopamine replacement therapy and face limitations such as reduced efficacy over time and adverse side effects. To address these challenges, we identified selective dopamine receptor subtype 4 (D4R) antagonists not previously reported as potential adjuvants for PD management. In this study, a library screening and artificial neural network quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) modeling with experimentally driven library design resulted in a class of spirocyclic compounds to identify candidate D4R antagonists. However, developing selective D4R antagonists suitable for clinical translation remains a challenge.

Keywords: dopamine receptors, D4R antagonism, Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a debilitating neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive motor dysfunction resulting from the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra.1,2 The resulting dopamine deficiency leads to the classic motor symptoms of PD, including bradykinesia, resting tremors, and rigidity.1 While current treatments, such as enhancing dopamine signaling and providing dopamine replacement therapy, have been effective in alleviating motor symptoms in the early stages of PD, the need for innovative therapeutic approaches is underscored by the challenges of maintaining their long-term efficacy and minimizing the risk of side effects, including medication-induced dyskinesias.2,3 One promising avenue of exploration lies in the design and development of selective dopamine receptor subtype 4 (D4R) antagonists as potential adjuvants for PD management.4−6

Dopamine receptors are divided into two families based on structural similarities, function, and pharmacological properties: the D1-like receptor family, which includes primarily the D1R and D5R subtypes, and the D2-like receptor family, which includes D2R, D3R, and D4R.7−9 Functionally, these two families have opposing mechanisms, with D1-like receptors stimulating adenyl cyclase through Gαs signaling and D2-like receptors inhibiting adenyl cyclase through Gαi/o signaling.7 Further receptor subtype heterogeneity can be found at the level of genetic polymorphisms. D4R itself comprises 10 different genotypes, with D4.2, D4.4, and D4.7 being the most prevalent of these.10−12 The pharmacological management of PD currently focuses primarily on enhancing dopamine signaling through D2R, such as by providing dopamine precursor therapy with levodopa or through direct agonism with pramipexole or ropinirole.13−25

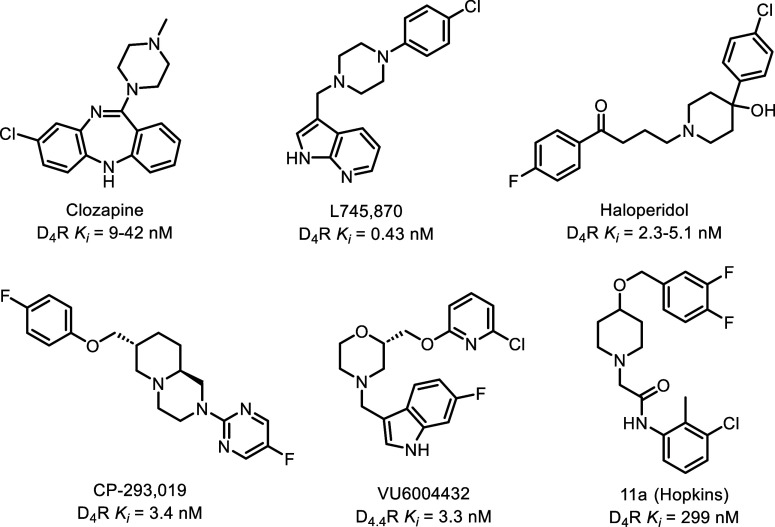

D4R has garnered increasing attention in recent years due to its distinctive expression pattern within the central nervous system and its potential role in modulating dopamine signaling.5,6,26 Unlike other dopamine receptor subtypes, D4R is primarily located in the frontal cortex and limbic system, areas that are associated with cognitive and emotional processes, and consequently has been implicated largely in neuropsychiatric conditions (though D4R is also expressed in the periphery).27−40 Early D4R antagonists were considered as potential therapeutic avenues for diseases such as addiction and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).41−44 Additionally, due to the expression of D4R within the basal ganglia, which is associated with the development of dyskinesias in PD patients, research has also unveiled the involvement of D4R in motor control, making it a compelling target in the context of PD for the treatment of levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID).3,4,33,45−48 Consequentially, interest in the development of selective D4R antagonists has increased in recent decades, selected examples of which can be seen in Figure 1. The approved antipsychotics clozapine and haloperidol have also been included for reference due to their historical significance, though these are not selective for D4R.9,30,49−59

Figure 1.

Selected historical compounds demonstrating antagonism at D4R.9,30,49−59

The central challenge in designing D4R antagonists as an adjuvant therapy for PD lies in obtaining selectivity for D4R over the other dopamine receptor subtypes, action at which could produce undesired side effects. For instance, antagonism or partial agonism of D2R has been demonstrated to worsen Parkinsonism, while action at D1R in conjunction with levodopa administration is associated with increased LID severity.60−64 Therefore, the pursuit of D4R antagonists for PD therapy demands meticulous attention to the selectivity and efficacy of the designed compounds. Recent advances in synthetic chemistry, structural biology, and pharmacology have enabled the design and characterization of diverse selective D4R antagonists, as exemplified in several key studies.59,65−69 Building off of these rich structure–activity relationship data, we disclose herein the development of a novel class of potent, selective D4R antagonists suitable for further preclinical optimization.

Results

Ligand-Based Ultralarge Library Screening to Identify Candidate D4R Antagonists

To identify new D4R antagonists, we first performed ligand-based ultralarge library screening using multitask classification artificial neural network (ANN) quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models (see Computational Methods and Materials in the Supporting Information). We trained four unique QSAR models on publicly available confirmatory screening data (molecules had reported IC50 and/or Ki/Kd values) from PubChem, one each for D2R, D3R, D4R, and D5R. Each model was trained to predict the likelihood that a molecule is active at or below the following thresholds: 1, 10, 100, 1000, and 10,000 nM. Two primary metrics guided our analysis: (1) the probability that a molecule is active against D4R at or below 10 nM and (2) the predicted selectivity for D4R, where selectivity is given by the equation below.

where PD4R,10nM is the QSAR-predicted probability of a molecule to be active at or below 10 nM, PD4R,1000nM is the same metric for D2R at or below 1000 nM, etc. Our formulation of selectivity specifically evaluates the likelihood of a molecule being selective for D4R at 2 orders of magnitude (active at 10 nM D4R vs 1000 nM D2, D3, and D5).

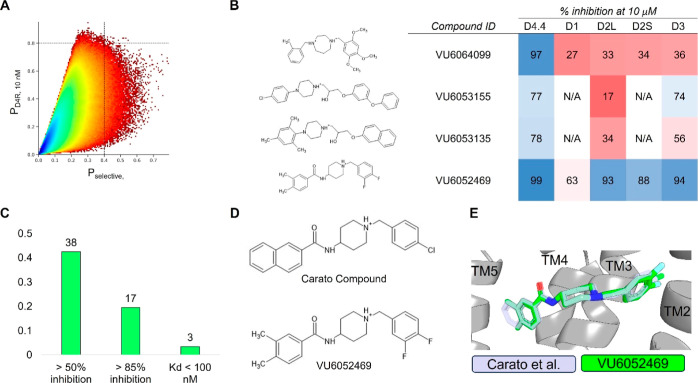

We applied our QSAR models to screen over 1 billion molecules sourced from LifeChemicals and the Enamine REAL database (Figure 2A). Compounds with 10 nM D4R activity prediction scores at or above 0.8 were moved forward for further analysis. Preference was given to compounds also exhibiting a selectivity score exceeding 0.4. We performed property-based flexible alignment70 of a subset of 500 molecules to the crystallographically bound pose of the D4R-selective antagonist L-745,870,68 followed by visual inspection. Ultimately, we chose 89 molecules to acquire from Enamine and LifeChemicals for experimental screening at Eurofins Discovery.

Figure 2.

Virtual high-throughput screening for D4R antagonists. (A) Predicted D4R activity vs selectivity from the ligand-based multitask ANN QSAR model ultralarge library virtual high-throughput screening. Dashed lines indicate QSAR-predicted active classification probabilities at or greater than 80% (horizontal) and 40% (vertical) for D4R 10 nM activity and overall selectivity, respectively. Plot color is contoured by the density of molecules, with higher-density regions appearing blue and lower-density regions appearing red. (B) Sample molecules identified during the virtual high-throughput screening. (C) D4R hit-rate for experimentally validated molecules. (D) 2D structures of Carato et al.: compound 22(71) and VU6052469. (E) Overlay of docked poses of Carato et al.: compound 22(71) and VU6052469 within D4R.

Our screening efforts yielded notable outcomes, with 38 of the selected molecules displaying inhibitory activity exceeding 50% at 10 μM and 17 (see Supporting Information for structures) showing greater than 85% inhibition at 10 μM for D4R (Figure 2B,C). Our success for identifying selective molecules was much lower. This is not unexpected as the selectivity metric is built from multiple independent predictions (eq S1), and thus, error from each prediction accumulates in the final score. Frequently, molecules predicted to be D4R selective were only selective against a single off-target subtype. Nonetheless, a subset of D4R-active compounds exhibited varying degrees of selectivity relative to at least one other dopamine receptor subtype (Figure 2B).

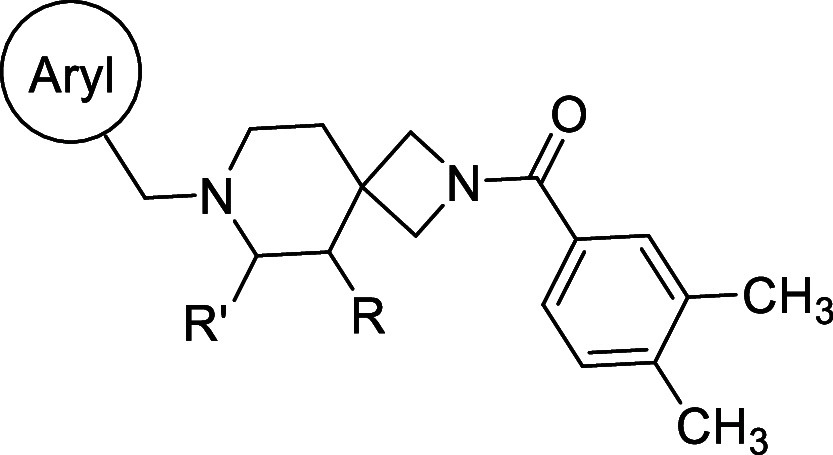

Identification of a Spirocyclic Core for D4R Antagonists

From our initial screen, we identified compound VU6052469, which is structurally similar to a previously published D4R antagonist by Carato et al. bearing a piperidine core with a naphthamide substituent that exhibits high potency and selectivity for D4R over D2R;71 however, VU6052469 itself is nonselective (Figure 2B,D). We docked VU6052469 and the Carato compound into D4R (PDB ID: 6IQL)68 to investigate the potential binding mode of our hit (Figure 2E). One challenge with designing D4R antagonists is the topological pseudosymmetry of D4R-active compounds, which in the case of VU6052469 and the Carato compound entails two distal aryl rings linked to a piperidine core (Figure 2D). In principle, this symmetry could enable the molecules to bind such that the halogen-substituted phenyl ring interacts with either transmembrane helices 2 (TM2) and TM3 (Figure S103A) or alternatively with TM4/5/6 (Figure S103B). In either binding pose, for example, VU6052469 hydrogen bonds with the conserved D3.32 side chain, and V3.33 can stack with its aromatic rings (Figure S103). The pocket formed by TM2/3 is hydrophobic and has previously been implicated in ligand selectivity.68,69 Indeed, the TM2/3 interface differs between D4R and D2R in that D2R contains aromatic ring side chains, while in D4R, there are aliphatic chains (Figure S104). In contrast, the amino acid composition of TM4/5/6 is a mixture of polar and hydrophobic residues. Notably, a cluster of serine residues engaged in internal backbone hydrogen bonds in TM5/6 renders this portion of the pocket more sterically accessible.

We reasoned that the latter pose is less likely as it induces a greater loss of planarity of the amide linker within the docked pose, which is supported by density functional theory (DFT) conformational stability calculations and molecular orbital analysis performed at the wB97X-D/6-311G(d,p) level of theory72 (Figure S103C,D). We estimate that the first pose of VU6052469 (Figure S103A) is 11.3 kcal/mol more energetically favorable, and it follows that the Carato compound adopts a similar binding conformation (Figure 2E). Despite being nonselective, our docked poses suggest that VU6052469 could readily be made selective through extending the amide bond via a methylene linker and truncating the arene without altering the orientation of the ligand within the binding pocket. To that end, we replaced the secondary amide with an azetidine amide to give a 2,7-diazaspiro[3.5]nonane core, resulting in compound 4, which displayed selectivity for D4R with only a partial loss of on-target activity (Table 1).

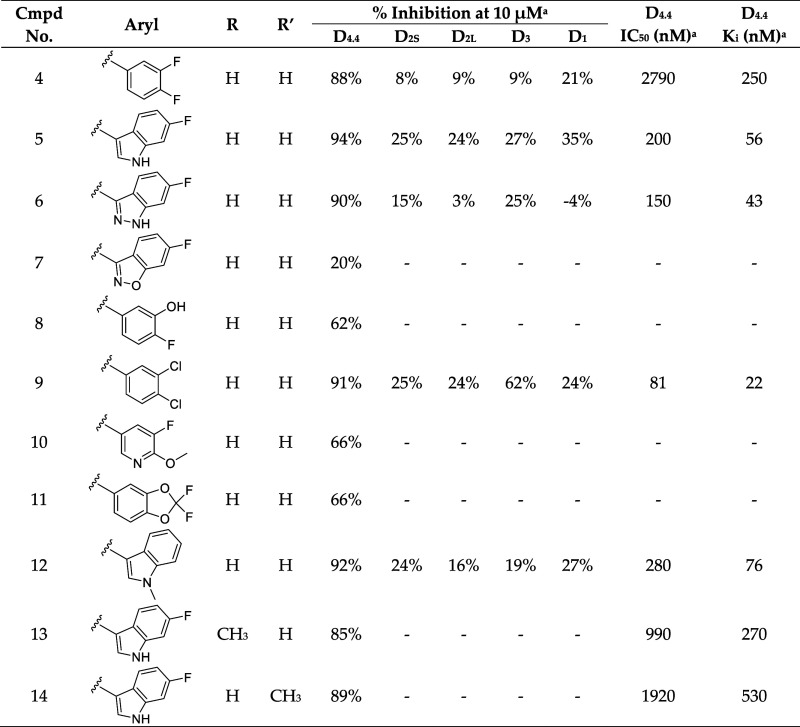

Table 1. Southern Region SAR.

Values were obtained from Eurofins Discovery. See Supporting Information for more details.

To better understand the mechanism of selectivity imparted by the spirocyclic core, we docked 4 into D4R and D2R (see Supporting Information) (Figure 3A–C). We verified the binding mode by running molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and analyzing ligand root-mean-square-deviation (rmsd) over time (Figure S105). Our docked poses suggest that the difluorophenyl of 4 differentially engages the TM2/3 hydrophobic pocket in D4R versus D2R. Compared to its complex with D4R, in the D2R complex 4 is shifted deeper into the TM2/3 pocket such that the hydrogen bond geometry between the orthosteric pocket aspartate D3.32 and the protonated piperidine is suboptimal (Figure S106). We confirmed that the D2R electrostatic interactions are less favorable than D4R by performing geometry optimization and subsequent interface energy calculations of the complexes using the semiempirical quantum mechanics (QM) tight-binding density functional theory (DFTB) method with dispersion corrections, DFTB3-D3(BJ) (Figure 3D) (see Supporting Information).73,74 The interaction energies of 4 with respect to the conserved central aspartate D3.32 and TM2/3 hydrophobic pocket in D4R and D2R are estimated to be −24.46 and −18.53 kcal/mol, respectively (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

SAR analysis of D4R selective antagonists. (A) Chemical structure of the spirocyclic compound 4. (B) Docked pose of compound 4 (green) in D4R. (C) Docked pose of compound 4 (green) in D2R. (D) DFTB3-D3(BJ) interaction energy (kcal/mol) between compound 4 and the central aspartate and TM2/TM3 hydrophobic pocket of D4R (purple) and D2R (blue). Docked poses of compounds (E) 5, (F) 20, and (G) 33.

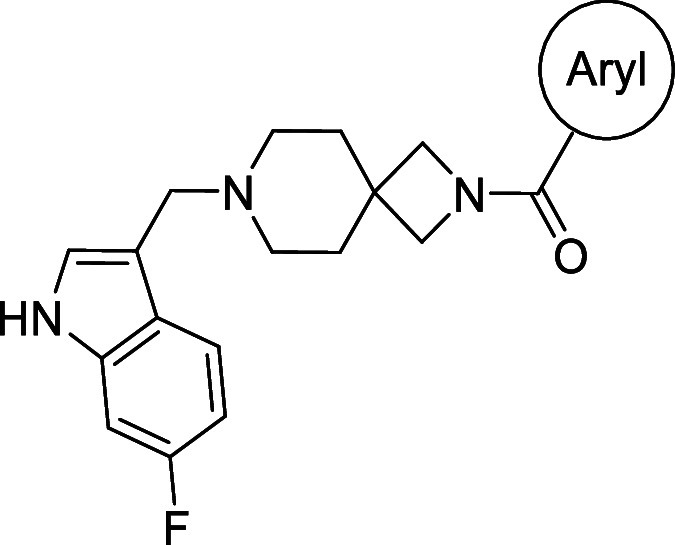

Optimization of Spirocyclic D4R Antagonist Potency and Selectivity

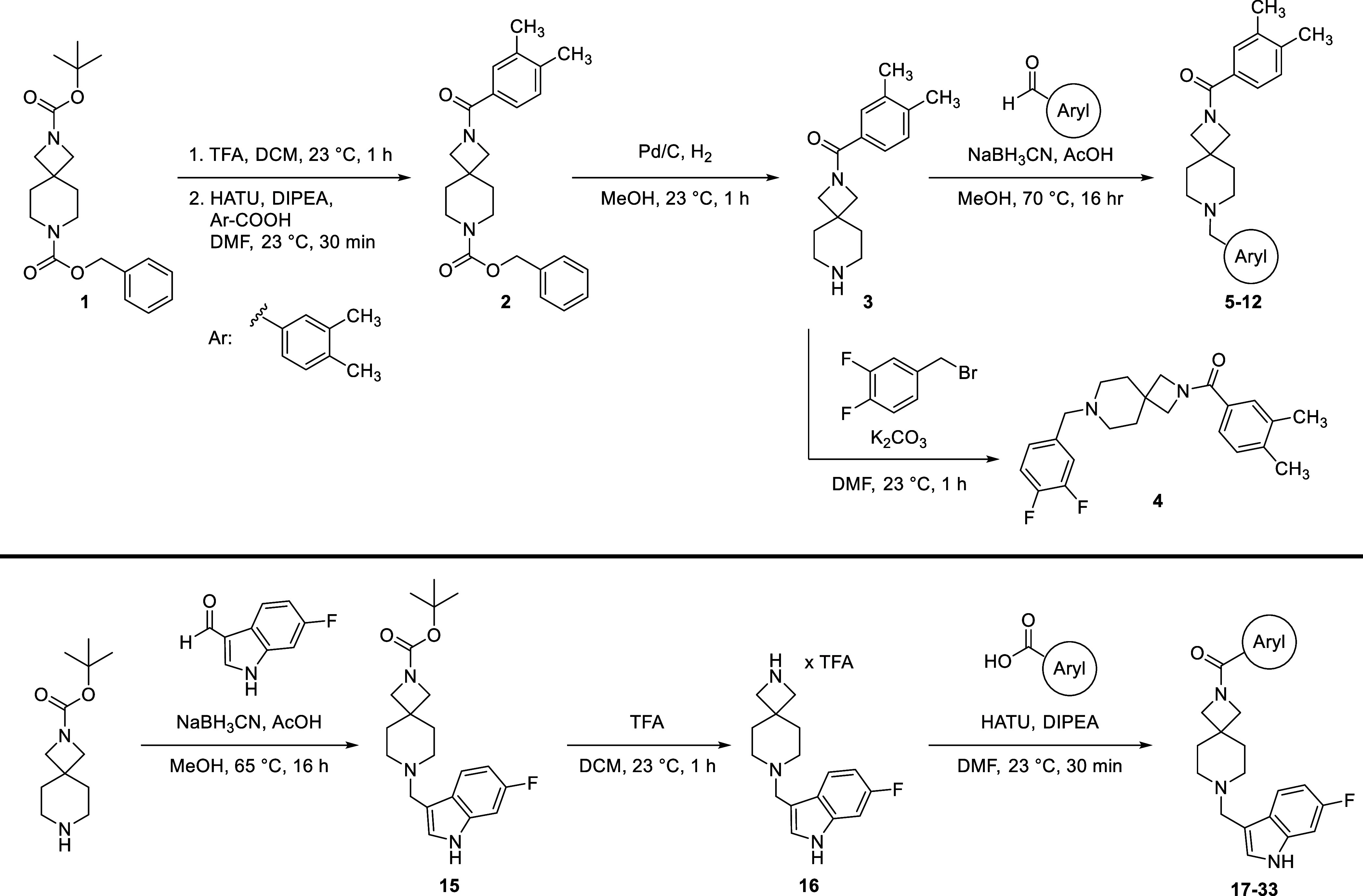

We sought to improve upon the potency and selectivity of 4 by screening analogues with differing polar aromatic or heteroaromatic groups on the southern end of the compound, installing methyl groups at the 2 or 3 position of the piperidine and probing the effect of the substitution pattern and substituent type on the northern phenyl ring on activity (Tables 1 and 2). The general synthetic scheme for this class of compounds is shown in Scheme 1, and detailed experimental procedures are provided in the Supporting Information for all intermediates and final compounds as well as compound 1. Briefly, compound 1 underwent TFA-mediated boc-deprotection followed by HATU amide coupling to afford intermediate 2. Subsequent benzyloxycarbonyl removal via hydrogen over palladium reduction gave key intermediate 3, which was subjected to either reductive amination with assorted aryl aldehydes to afford compounds 5–12 or an SN2 reaction with 3,4-difluorobenzyl bromide to provide compound 4. To obtain azetidine amides 17–33, commercially available tert-butyl 2,7-diazaspiro[3.5]nonane-2-carboxylate was subjected to reductive amination with 6-fluoro-1H-indole-3-carbaldehyde to give intermediate 15. Boc-deprotection with TFA afforded 16, which then underwent HATU amide coupling with assorted aryl carboxylic acids to give compounds 17–34.

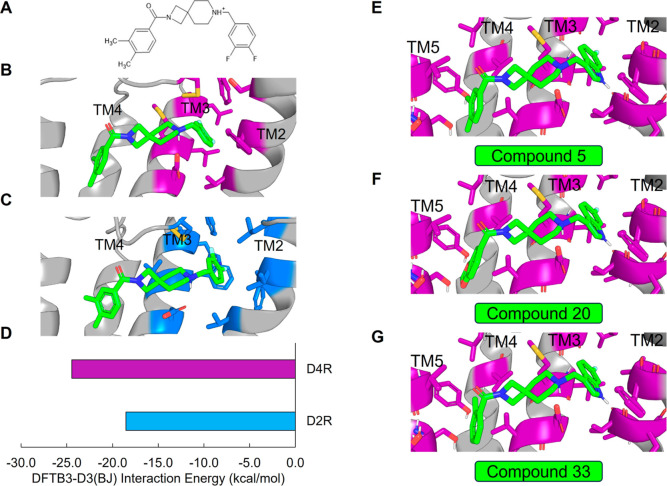

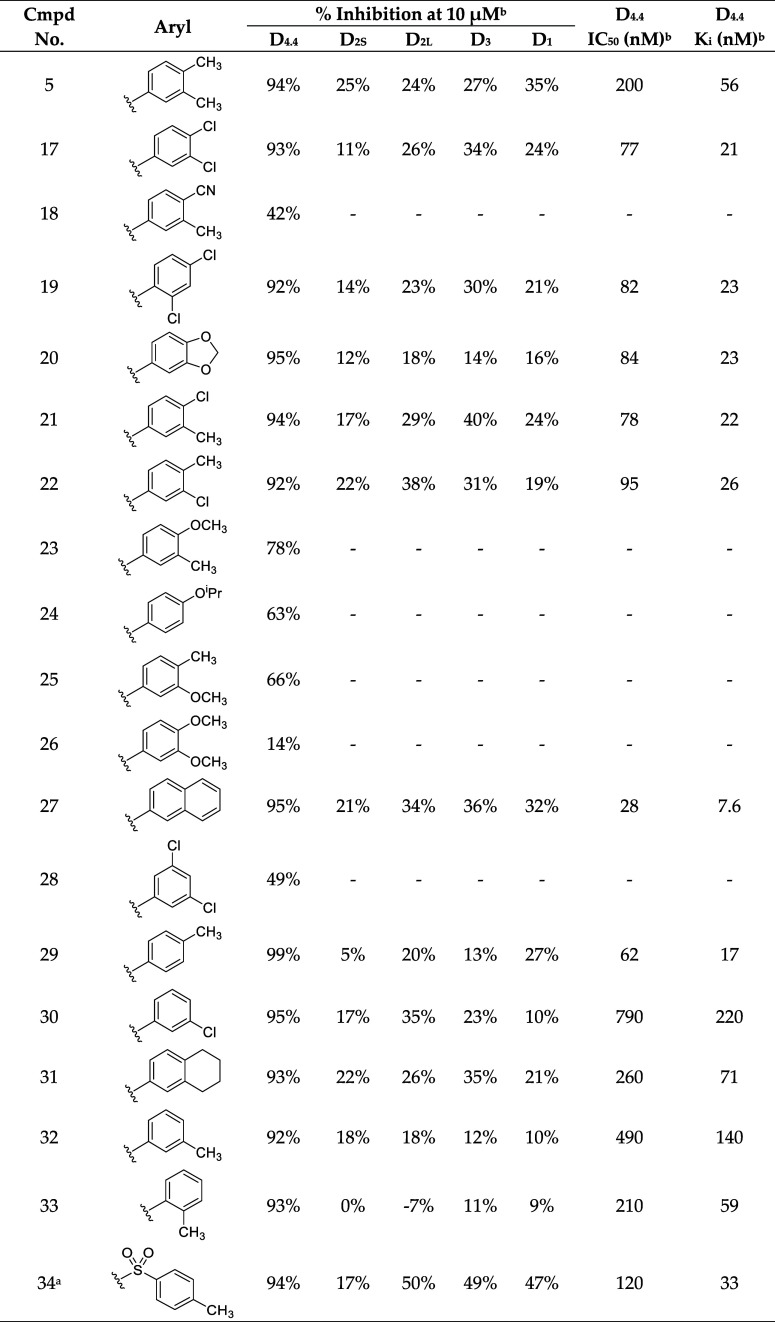

Table 2. Northern Ring SAR.

Structure for this compound is a sulfonamide bound to the azetidine nitrogen of the spirocycle.

Values were obtained from Eurofins Discovery. See Supporting Information for more details.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Diazaspiro[3.5]nonane D4R Antagonists.

Overall, this focused collection of spirocyclic antagonists provided a number of valuable SAR insights. With respect to the southern region, replacing the difluorophenyl moiety with the analogous dichlorophenyl substituent (9) resulted in significantly increased activity; however, a significant decrease in selectivity between the DR subtypes was also observed. Incorporation of other substituted arenes, such as fluorophenol (8), benzodioxole (11), and fluoropyridine (10), resulted in a steep decrease in inhibition (Table 1). By installing a 6-fluoroindole heterocycle (5) as we used previously in our morpholine core D4R antagonist (VU6004432, Figure 1),58 we observed drastically improved activity over 4, though the overall selectivity was mildly decreased. Exchanging the indole for an indazole 6 resulted in an improvement in the selectivity against all subtypes, with a mild improvement in activity at D4.4R. This is in stark contrast to the incorporation of benzisoxazole (7), which essentially abolishes activity. Modifications to the spirocyclic core were not favorable as the addition of methyl groups to the 2 or 3 position of the piperidine ring (compounds 14 and 13, respectively) significantly reduced the potency and affinity of the compound compared to that observed with 5 (Table 1), while expansion of the azetidine to a pyrrolidine led to a substantial decrease in inhibitory activity (compound 42; see Supporting Information).

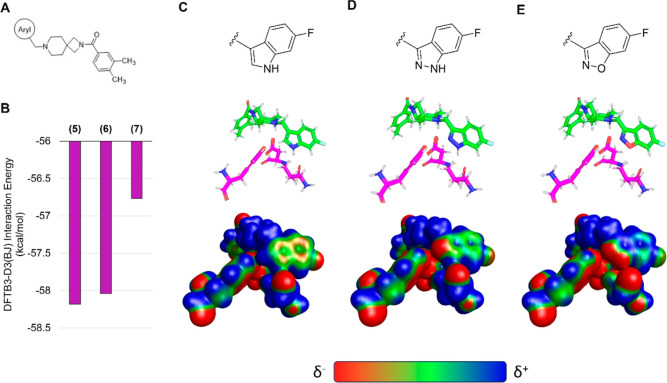

To better understand the differences in activity between 5, 6, and 7, we first docked 5 to D4R. Once again, pseudosymmetry within 5 rendered two flipped binding modes plausible. The first binding mode (Figure 3E) follows from the predicted poses of VU6052469 and 4. Interestingly, however, an alternative binding mode in which the indole ring of 5 adopts a pose mimicking the experimentally determined bound pose of L745,87068 is also possible. To determine which pose is more likely, we performed MD simulations starting from each docked pose. We observed that the pose consistent with 4 (Figure 3E) is more likely to remain near the docked binding pose (Figure S107A,B) and adopt favorable hydrogen bond geometry with D3.32 (Figure S107C,D). Furthermore, the interaction energy rankings for this binding mode (Figure 3E) are consistent with the experimental results and demonstrate the activity cliff in 7 (Table 1 and Figure 4A,B). In contrast, the binding mode mimicking the L745,870 pose yields interaction energy estimates inconsistent with experiment (data not shown). Visualization of the surface electrostatic potentials of D4R complexed with 5, 6, or 7 at the DFT wB97X-D/6-31G(d) level of theory72 suggests that this activity cliff is due to loss of complementary electrostatic interactions and an abundance of anionic charge near TM2 (Figure 4C–E).

Figure 4.

Surface electrostatics analysis of D4R selective antagonists in complex with D4R. (A) Schematic southern aryl substitution on compound 4. (B) Interaction energies for the model systems containing compounds 5, 6, or 7. Surface electrostatic potential analysis of (C) compound 5, (D) compound 6, and (E) compound 7. Electrostatic potentials are calculated for model systems (C–D) at the wB97X-D/6-31G(d) level of theory with solvation model density (SMD) aqueous implicit solvent following geometry optimization of the receptor pocket and ligand in complex utilizing DFTB3-D3(BJ) with SMD solvent water.

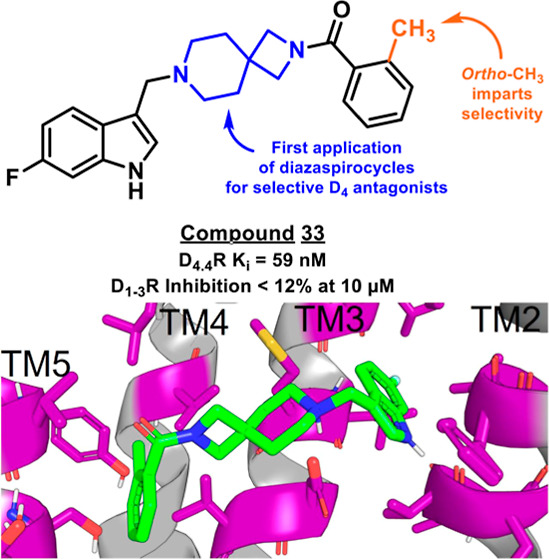

While indazole antagonist 6 provided the best potency and selectivity profile thus far, we proceeded with the combination of the 6-fluoroindole southern ring and the unmodified 2,7-diazaspiro[3.5]nonane core for exploration of the northern region SAR as 5 performed similarly and was more cost-effective for library synthesis. Therefore, we employed 5 as a starting point for pursuing a focused library of aryl amides on the northern end of the scaffold for further improvement of DR subtype selectivity (Table 2). Overall, alkyl and chloro substituents were well-tolerated, with the sole exception of the 3,5-dichlorophenyl analogue (28), which demonstrated drastically reduced inhibitory activity (49%). The 2,4-dichlorophenyl regioisomer (19) retained activity, however, indicating that D4.4R inhibition is sensitive to subtle changes in substitution pattern in this region. In contrast to alkyl and chloro groups, incorporation of alkoxy groups generally led to a significant reduction in activity against D4.4R (23–26), with the sole exception being 20 (Figure 3F), which bears a benzodioxole heterocycle (D4.4R IC50 = 84 nM; Ki = 23 nM). The potency of benzodioxole-bearing compound 20 suggests that the lack of activity observed in compounds 23–26 is a result of unfavorable steric interactions facilitated by their freely rotating alkyl groups rather than ring electronics. In addition to the benzodioxole example (20), increasing the size of the aryl amide from a monocycle to a fused bicycle in other instances was also well tolerated (27, 31), with naphthalene 27 exhibiting particularly potent activity (D4.4R IC50 = 28 nM; Ki = 7.6 nM). With respect to selectivity, a strong sensitivity to regioisomerism was observed, which was most clearly demonstrated in compounds 29, 32, and 33, which bear para-, meta-, and ortho-toluamides, respectively. Of these, compound 29 demonstrates the highest D4.4R activity (D4.4R IC50 = 62 nM; Ki = 17 nM), and it exhibits a moderately improved selectivity profile over 5. Both meta and ortho isomers (compounds 32 and 33, respectively) display reduced activity compared to para isomer 29. Compound 33 (Figure 3G), however, exhibited the best selectivity profile of all compounds disclosed herein, with a notable 0% activity against D2S. It was also observed that replacement of the para-toluamide of 29 with a tosylamide (34) mildly reduced the D4.4R activity but notably increased the inhibitory activity at all other tested DR subtypes, possibly due to the reduced planarity of the sulfonamide.

In Vitro and In Vivo DMPK Analysis of Selected Compounds

A subset of compounds that demonstrated high potency and excellent selectivity were selected for pharmacokinetic characterization (Table 3). In vitro stability experiments in rat and human microsomes returned high clearance (>70% Qh) across all compounds, except for 20, which exhibited moderate hepatic clearance (CLH of 13.7 and 36.2 in human and rat microsomes, respectively). The free fraction in plasma ranged from 1 to 19% in rat and 3–26% in human. Notably, both compounds 33 and 20 exhibited increased free fractions compared to the original hit (4). Three compounds (4, 20, and 33) were selected to assess in vivo pharmacokinetics (compounds 29 and 32 were excluded as they exhibited worse free fraction in plasma compared to 20 and 33). Upon intravenous dosing in rats, all three compounds demonstrated superhepatic clearance (>100% Qh). This result is consistent with these compounds experiencing high hepatic metabolic clearance and may also indicate contribution to clearance through a different route, such as extrahepatic metabolism or active direct excretion. Despite high clearance, compounds 4, 20, and 33 exhibited moderate to high distribution into tissues (volume of distributions of 5.52, 44.4, and 36.9 L/kg, respectively), explaining the reasonable half-lives for these compounds (1.05, 4.55, and 4.02 h, respectively).

Table 3. In Vivo and In Vitro Results of Selected Compounds.

| compound |

fu,plasmaa |

CLHa (mL/min/kg) |

CLpa (mL/min/kg) | t1/2a (h) | Vssa (L/kg) | AUCa (h·ng/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| human | rat | human | rat | |||||

| 4 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 16.9 | 59.1 | 116 | 1.05 | 5.52 | 28.7 |

| 33 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 16.0 | 39.0 | 123 | 4.02 | 36.9 | 27.0 |

| 32 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 14.7 | 46.2 | ||||

| 29 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 17.3 | 49.2 | ||||

| 20 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 13.7 | 36.2 | 126 | 4.55 | 44.4 | 26.4 |

fu = Fraction unbound; equilibrium dialysis assay; CLH = hepatic clearance; CLp = plasma clearance; t1/2 = terminal phase plasma half-life; Vss = volume of distribution at steady-state; AUC = area under the curve.

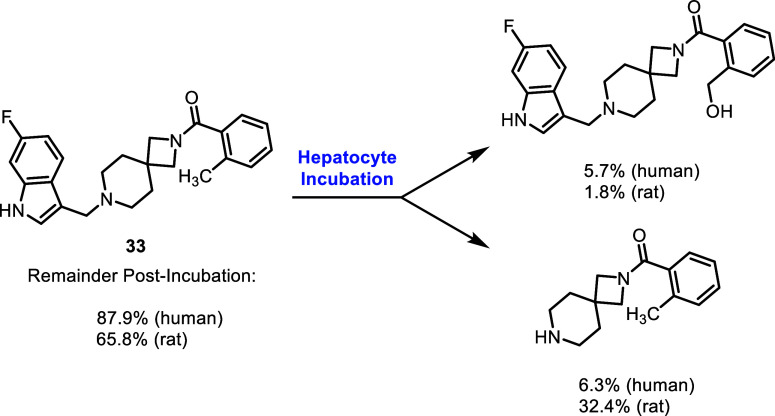

Compound 33 was subjected to metabolite profiling in human and rat hepatocytes to provide insight into potential clearance mechanisms and metabolic liabilities (Figure 5). After incubation for 4 h, 33 exhibited low turnover in human hepatocytes and moderate turnover in rat hepatocytes, with 87.9 and 65.8% of parent compound (33) remaining postincubation, respectively. In both species, only two major metabolites were observed: mono-oxidation of the benzylic methyl group and piperidine N-dealkylation. The latter means of metabolism was elevated in rats (32.4%) compared to that in humans (6.3%).

Figure 5.

Metabolite analysis of compound 33 in human and rat hepatocytes. Parent compound incubated in human or rat hepatocytes for 4 h. Percentages (determined via LC/MS) indicate the relative percentage of compounds present postincubation. See Supporting Information for details.

Discussion

The application of spirocycles to drug discovery efforts has increased in recent years as a means to increase compound three-dimensionality, modulate DMPK properties, incorporate additional sp3 centers, and generate novel intellectual property.75−78 One of the central findings of the present study was the discovery of 2,7-diazaspiro[3.5]nonane as an applicable core motif for selective D4R antagonists. While we initially identified the highly potent antagonist VU6052469, which exhibited a high degree of structural similarity to a previously reported selective D4R antagonist,71 it notably lacked selectivity (Figure 2B,D,E). We postulated that this lack of selectivity arose from the difference in length between these two compounds, with the naphthalene and 4-chlorobenzyl moieties of the Carato compound potentially leading to poorer steric interactions within the TM2/3 pocket of D2R than the dimethylphenyl and 3,4-difluorobenzyl moieties of VU6052469 (Figure 2E). By replacing the core piperidine of VU6052469 with 2,7-diazaspiro[3.5]nonane, the dimethylphenyl ring is extended further into the TM4/5/6 pocket, affording potent and selective activity against D4R (Table 1). While there have been reported examples of substituted diazaspirocycles bearing D4R activity, this activity was not the desired mode of action (i.e., the intent was to target σ receptors) nor did the more potent compounds exhibit DR subtype selectivity.79 Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the use of diazaspirocycles in pursuit of selective D4R antagonists.

Interestingly, our investigation revealed an activity cliff when comparing the indole/indazole- vs benzisoxazole-substituted compounds (compounds 5/6 and 7, respectively). Activity cliffs are subtle structural changes leading to significant alterations in inhibitory activity. In this case, the subtle difference in ligand interaction energies with the receptor went undetected by the docking score function. It was only after performing geometry optimization and interaction energy calculations with the more computationally demanding semiempirical QM method DFTB3-D3(BJ) that we understood the case of the reduction in binding affinity, which was a result of an accumulation of anionic charge near TM2 with no available hydrogen bond donors. This example emphasizes the continued importance of developing force fields and/or deep learning algorithms for binding affinity prediction that can be used during rapid screening protocols.

A key challenge in the rational design of selective D4R antagonists is the topological pseudosymmetry displayed by most antagonists. This challenge is 2-fold: (1) highly similar antagonists may be oriented in conformations 180° opposed to one another, and (2) the internal pseudosymmetry of many D4R antagonists renders it difficult to ascertain their appropriate binding modes. Despite extensive computational validation, it is possible that our putative binding modes are inaccurate, which may lead to false structure–activity relationships. Further experimental structural evidence, such as crystal structures of these spirocyclic antagonists bound to D4R, will be valuable in the design of future D4R antagonists with similar potencies and selectivity.

Modifications to the northern aryl amide of this scaffold demonstrated the sensitivity of D4R potency and selectivity to ring substituent choice and regioisomerism. Overall, compound 33, which bears an ortho-toluamide northern substituent, displayed the best selectivity profile of the tested compounds while retaining potent D4.4R antagonism and affinity (IC50 = 210 nM; Ki = 59 nM). Though our study has yielded promising D4R antagonists such as this, an ongoing challenge in the design of this class of compounds is the optimization of pharmacokinetic properties. While this class of compounds exhibited excellent aqueous solubility (see Supporting Information), both in vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic analysis of selected compounds demonstrated a key limitation of the present class: high metabolic clearance. The findings of these assays underscore the need for continued efforts to improve the pharmacokinetic profiles of potential D4R antagonist drug candidates, most likely via design changes to remove metabolic hotspots within this chemical series.

Altogether, our study has unveiled a spirocyclic core for D4R selective antagonists, providing a foundation for further drug development efforts in the context of PD. Our insight into DR subtype selectivity and activity cliffs offers valuable guidance for future research in this area. The improvement of spirocyclic D4R antagonist DMPK properties, however, remains requisite for the development of a suitable preclinical lead within this class as a potential adjuvant therapy for PD.

Acknowledgments

B.P.B. is supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH NIDA DP1DA058349). J.M. is supported by a Humboldt Professorship of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, and research in the Meiler Lab at Vanderbilt University is supported by the NIH (NIDA R01DA046138, NLM R01LM013434, NCI R01CA227833, and NIGMS R01GM080403). J.M. acknowledges funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through SFB1423 (421152132). J.M. is supported by BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research) through the Center for Scalable Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence (ScaDS.AI). This work is partly supported by BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research) through DAAD project 57616814 (SECAI, School of Embedded Composite AI). High-performance computing at Vanderbilt’s ACCRE facility is supported through NIH S10 OD016216, NIH S10 OD020154, and NIH S10 OD032234. Authors would also thank the William K. Warren Family and Foundation for founding the William K. Warren Jr. Chair in Medicine and endowing the WCNDD and support of our programs. We would like to thank Jeremy Turkett for performing the metabolite profiling of compound 33 and Christopher Presley for performing the kinetic solubility assays.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschemneuro.4c00086.

Experimental procedure for the synthesis of compounds, 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra for all compounds, 2D NMR (NOESY, HMBC, HSQC, and COSY) for compounds that required further characterization, DMPK experimental methods, computational methods, and metabolite profiling (PDF)

Author Contributions

¶ C.A.H.J., B.P.B., and D.C.S. contributed equally to this work and are listed as co-first authors. C.A.H.J. and D.C.S. contributed to the synthesis and characterization of all the compounds. B.P.B. contributed through the modeling of the various D4R antagonists in silico. J.E. organized the samples shipment to Eurofins and worked up the data for percent inhibition, Ki and IC50. V.M.K. contributed by the design and experimentation of DMPK evaluation. J.M. and C.W.L. conceived the study and contributed as project leads.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gelb D. J.; Oliver E.; Gilman S. Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinson Disease. Arch. Neurol. 1999, 56 (1), 33. 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. K.; Yankee E. L. A Review on Parkinson’s Disease Treatment. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflammation 2022, 8, 222. 10.20517/2347-8659.2020.58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huot P.; Johnston T. H.; Koprich J. B.; Fox S. H.; Brotchie J. M. The Pharmacology of L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia in Parkinson’s Disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65 (1), 171–222. 10.1124/pr.111.005678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastianutto I.; Maslava N.; Hopkins C. R.; Cenci M. A. Validation of an Improved Scale for Rating L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia in the Mouse and Effects of Specific Dopamine Receptor Antagonists. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 96, 156–170. 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley C. W.; Hopkins C. R. Return of D4 Dopamine Receptor Antagonists in Drug Discovery: Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (17), 7233–7243. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgioni G.; Del Bello F.; Pavletić P.; Quaglia W.; Botticelli L.; Cifani C.; Micioni Di Bonaventura E.; Micioni Di Bonaventura M. V.; Piergentili A. Recent Findings Leading to the Discovery of Selective Dopamine D4 Receptor Ligands for the Treatment of Widespread Diseases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 212, 113141. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.113141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebabian J. W. Multiple Classes of Dopamine Receptors in Mammalian Central Nervous System: The Involvement of Dopamine-Sensitive Adenylyl Cyclase. Life Sci. 1978, 23 (5), 479–483. 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C.; Nash S. R.; Robinson S. W.; Jaber M.; Caron M. G. Dopamine Receptors: From Structure to Function. Physiol. Rev. 1998, 78 (1), 189–225. 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallone D.; Picetti R.; Borrelli E. Structure and Function of Dopamine Receptors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000, 24 (1), 125–132. 10.1016/S0149-7634(99)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tol H. H. M. V.; Wu C. M.; Guan H.-C.; Ohara K.; Bunzow J. R.; Civelli O.; Kennedy J.; Seeman P.; Niznik H. B.; Jovanovic V. Multiple Dopamine D4 Receptor Variants in the Human Population. Nature 1992, 358 (6382), 149–152. 10.1038/358149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F.-M.; Kidd J. R.; Livak K. J.; Pakstis A. J.; Kidd K. K. The World-Wide Distribution of Allele Frequencies at the Human Dopamine D4 Receptor Locus. Hum. Genet. 1996, 98 (1), 91–101. 10.1007/s004390050166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.-C.; Chi H.-C.; Grady D. L.; Morishima A.; Kidd J. R.; Kidd K. K.; Flodman P.; Spence M. A.; Schuck S.; Swanson J. M.; Zhang Y.-P.; Moyzis R. K. Evidence of Positive Selection Acting at the Human Dopamine Receptor D4 Gene Locus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99 (1), 309–314. 10.1073/pnas.012464099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. S.; Mierau J. Dopamine Autoreceptor Agonists: Resolution and Pharmacological Activity of 2,6-Diaminotetrahydrobenzothiazole and an Aminothiazole Analog of Apomorphine. J. Med. Chem. 1987, 30 (3), 494–498. 10.1021/jm00386a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierau J.; Schingnitz G. Biochemical and Pharmacological Studies on Pramipexole, a Potent and Selective Dopamine D2 Receptor Agonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992, 215 (2–3), 161–170. 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierau J.; Schneider F. J.; Ensinger H. A.; Chio C. L.; Lajiness M. E.; Huff R. M. Pramipexole Binding and Activation of Cloned and Expressed Dopamine D2, D3 and D4 Receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol., Mol. Pharmacol. Sect. 1995, 290 (1), 29–36. 10.1016/0922-4106(95)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J. P.; Piercey M. F. Pramipexole — a New Dopamine Agonist for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999, 163 (1), 25–31. 10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonini A.; Barone P.; Ceravolo R.; Fabbrini G.; Tinazzi M.; Abbruzzese G. Role of Pramipexole in the Management of Parkinsonʼs Disease:. CNS Drugs 2010, 24 (10), 829–841. 10.2165/11585090-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frampton J. E. Pramipexole Extended-Release: A Review of Its Use in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Drugs 2014, 74 (18), 2175–2190. 10.1007/s40265-014-0322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher G.; Lavanchy P. G.; Wilson J. W.; Hieble J. P.; DeMarinis R. M. 4-[2-(Di-n-Propylamino)Ethyl]-2(3H)-Indolone: A Prejunctional Dopamine Receptor Agonist. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28 (10), 1533–1536. 10.1021/jm00148a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden R. J.; Costall B.; Domeney A. M.; Gerrard P. A.; Harvey C. A.; Kelly M. E.; Naylor R. J.; Owen D. A. A.; Wright A. Preclinical Pharmacology of Ropinirole (SK&F 101468-A) a Novel Dopamine D2 Agonist. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1991, 38 (1), 147–154. 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90603-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy M. Update on ropinirole in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 33, 33. 10.2147/NDT.S3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk C. LXV.—Synthesis of Dl-3:4-Dihydroxyphenylalanine. J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 1911, 99 (0), 554–557. 10.1039/CT9119900554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birkmayer W.; Hornykiewicz O. The L-3,4-dioxyphenylalanine (DOPA)-effect in Parkinson-akinesia. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 1961, 73, 787–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornykiewicz O. L-DOPA: From a Biologically Inactive Amino Acid to a Successful Therapeutic Agent. Amino Acids 2002, 23 (1–3), 65–70. 10.1007/s00726-001-0111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambasco N.; Romoli M.; Calabresi P. Levodopa in Parkinson’s Disease: Current Status and Future Developments. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16 (8), 1239–1252. 10.2174/1570159X15666170510143821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T. C.; Kruzich P. J.; Joyce B. M.; Gash C. R.; Suchland K.; Surgener S. P.; Rutherford E. C.; Grandy D. K.; Gerhardt G. A.; Glaser P. E. A. Dopamine D4 Receptor Knockout Mice Exhibit Neurochemical Changes Consistent with Decreased Dopamine Release. J. Neurosci. Methods 2007, 166 (2), 306–314. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman N. P.; Robbins T. W. The Role of Prefrontal Cortex in Cognitive Control and Executive Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47 (1), 72–89. 10.1038/s41386-021-01132-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajmohan V.; Mohandas E. The Limbic System. Indian J. Psychiatry 2007, 49 (2), 132–139. 10.4103/0019-5545.33264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley K. L.; Harmon S.; Tang L.; Todd R. D. The Rat Dopamine D4 Receptor: Sequence, Gene Structure, and Demonstration of Expression in the Cardiovascular System. New Biol. 1992, 4 (2), 137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tol H. H. M.; Bunzow J. R.; Guan H.-C.; Sunahara R. K.; Seeman P.; Niznik H. B.; Civelli O. Cloning of the Gene for a Human Dopamine D4 Receptor with High Affinity for the Antipsychotic Clozapine. Nature 1991, 350 (6319), 610–614. 10.1038/350610a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. I.; Todd R. D.; Harmon S.; O’Malley K. L. Photoreceptors of Mouse Retinas Possess D4 Receptors Coupled to Adenylate Cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89 (24), 12093–12097. 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M.; Hidaka K.; Tada S.; Tasaki Y.; Yamaguchi T. Full-Length cDNA Cloning and Distribution of Human Dopamine D4 Receptor. Mol. Brain Res. 1995, 29 (1), 157–162. 10.1016/0169-328X(94)00245-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrzljak L.; Bergson C.; Pappy M.; Huff R.; Levenson R.; Goldman-Rakic P. S. Localization of Dopamine D4 Receptors in GABAergic Neurons of the Primate Brain. Nature 1996, 381 (6579), 245–248. 10.1038/381245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariano M. A.; Wang J.; Noblett K. L.; Larson E. R.; Sibley D. R. Cellular Distribution of the Rat D4 Dopamine Receptor Protein in the CNS Using Anti-Receptor Antisera. Brain Res. 1997, 752 (1–2), 26–34. 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)01422-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek R.; Kuzelova H.; Stefano G. B. Dopamine D4 Receptor Gene DRD4 and Its Association with Psychiatric Disorders. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011, 17 (9), RA215–RA220. 10.12659/MSM.881925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defagot M. C.; Falzone T. L.; Low M. J.; Grandy D. K.; Rubinstein M.; Antonelli M. C. Quantitative Analysis of the Dopamine D4 Receptor in the Mouse Brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000, 59 (2), 202–208. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff J. H. Dopamine Receptor Transcript Expression in Striatum and Prefrontal and Occipital Cortex: Focal Abnormalities in Orbitofrontal Cortex in Schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54 (12), 1089. 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidow M. S.; Wang F.; Cao Y.; Goldman-Rakic P. S. Layer V Neurons Bear the Majority of mRNAs Encoding the Five Distinct Dopamine Receptor Subtypes in the Primate Prefrontal Cortex. Synapse 1998, 28 (1), 10–20. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primus R. J.; Thurkauf A.; Xu J.; Yevich E.; McInerney S.; Shaw K.; Tallman J. F.; Gallagher D. W. II. Localization and Characterization of Dopamine D4 Binding Sites in Rat and Human Brain by Use of the Novel, D4 Receptor-Selective Ligand [3H]NGD 94–1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997, 282 (2), 1020–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff J. H.; Grandy D. K.; Van Tol H. H. M.; Damask S. P.; Little K. Y.; Civelli O.; Watson S. J. Dopamine Receptor Gene Expression in the Human Medial Temporal Lobe. Neuropsychopharmacology 1994, 10 (4), 239–248. 10.1038/npp.1994.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P.; Grandy D. K.; Le Foll B.. Dopamine D4 Receptors in Psychostimulant Addiction. Advances in Pharmacology; Elsevier, 2014; Vol. 69, pp 301–321. 10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00008-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornick M. C.; Addington A.; Shaw P.; Bobb A. J.; Sharp W.; Greenstein D.; Arepalli S.; Castellanos F. X.; Rapoport J. L. Association of the Dopamine Receptor D4 (DRD4) Gene 7-repeat Allele with Children with Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): An Update. Am. J. Med. Genet., Part B 2007, 144B (3), 379–382. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; Davids E.; Tarazi F.; Baldessarini R. Effects of Dopamine D4 Receptor-Selective Antagonists on Motor Hyperactivity in Rats with Neonatal 6-Hydroxydopamine Lesions. Psychopharmacology 2002, 161 (1), 100–106. 10.1007/s00213-002-1018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avale M. E.; Falzone T. L.; Gelman D. M.; Low M. J.; Grandy D. K.; Rubinstein M. The Dopamine D4 Receptor Is Essential for Hyperactivity and Impaired Behavioral Inhibition in a Mouse Model of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2004, 9 (7), 718–726. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huot P.; Johnston T. H.; Koprich J. B.; Aman A.; Fox S. H.; Brotchie J. M. L-745,870 Reduces L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia in the 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine-Lesioned Macaque Model of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012, 342 (2), 576–585. 10.1124/jpet.112.195693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlij D.; Acosta-García J.; Rojas-Márquez M.; González-Hernández B.; Escartín-Perez E.; Aceves J.; Florán B. Dopamine D4 Receptor Stimulation in GABAergic Projections of the Globus Pallidus to the Reticular Thalamic Nucleus and the Substantia Nigra Reticulata of the Rat Decreases Locomotor Activity. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62 (2), 1111–1118. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastide M. F.; Meissner W. G.; Picconi B.; Fasano S.; Fernagut P.-O.; Feyder M.; Francardo V.; Alcacer C.; Ding Y.; Brambilla R.; Fisone G.; Jon Stoessl A.; Bourdenx M.; Engeln M.; Navailles S.; De Deurwaerdère P.; Ko W. K. D.; Simola N.; Morelli M.; Groc L.; Rodriguez M.-C.; Gurevich E. V.; Quik M.; Morari M.; Mellone M.; Gardoni F.; Tronci E.; Guehl D.; Tison F.; Crossman A. R.; Kang U. J.; Steece-Collier K.; Fox S.; Carta M.; Angela Cenci M.; Bézard E. Pathophysiology of L-Dopa-Induced Motor and Non-Motor Complications in Parkinson’s Disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015, 132, 96–168. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde Rojas I.; Acosta-García J.; Caballero-Florán R. N.; Jijón-Lorenzo R.; Recillas-Morales S.; Avalos-Fuentes J. A.; Paz-Bermúdez F.; Leyva-Gómez G.; Cortés H.; Florán B. Dopamine D4 Receptor Modulates Inhibitory Transmission in Pallido-pallidal Terminals and Regulates Motor Behavior. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 52 (11), 4563–4585. 10.1111/ejn.15020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward D. M. General Pharmacology of Clozapine. Br. J. Psychiatry 1992, 160 (S17), 5–11. 10.1192/S0007125000296840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S.; Freedman S.; Chapman K. L.; Emms F.; Fletcher A. E.; Knowles M.; Marwood R.; Mcallister G.; Myers J.; Curtis N.; Kulagowski J. J.; Leeson P. D.; Ridgill M.; Graham M.; Matheson S.; Rathbone D.; Watt A. P.; Bristow L. J.; Rupniak N. M.; Baskin E.; Lynch J. J.; Ragan C. I. Biological Profile of L-745,870, a Selective Antagonist with High Affinity for the Dopamine D4 Receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997, 283 (2), 636–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. S. The Effects of a Selective D4 Dopamine Receptor Antagonist (L-745,870) in Acutely Psychotic Inpatients With Schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54 (6), 567. 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830180085011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow L. J.; Collinson N.; Cook G. P.; Curtis N.; Freedman S. B.; Kulagowski J. J.; Leeson P. D.; Patel S.; Ragan C. I.; Ridgill M.; Saywell K. L.; Tricklebank M. D. L-745,870, a Subtype Selective Dopamine D4 Receptor Antagonist, Does Not Exhibit a Neuroleptic-like Profile in Rodent Behavioral Tests. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997, 283 (3), 1256–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen P. A. J.; Jageneau A. H. M.; Schellekens K. H. L. Chemistry and Pharmacology of Compounds Related to 4-(4-Hydroxy-4-Phenyl-Piperidino)-Butyrophenone: Part IV Influence of Haloperidol (R 1625) and of Chlorpromazine on the Behaviour of Rats in an Unfamiliar “Open Field” Situation. Psychopharmacologia 1960, 1 (5), 389–392. 10.1007/BF00441186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divry P.; Bobon J.; Collard J.; Pinchard A.; Nols E. Study & clinical trial of R 1625 or haloperidol, a new neuroleptic & so-called neurodysleptic agent. Acta Neurol. Psychiatr. Belg. 1959, 59 (3), 337–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen P. A. J.; Van De Westeringh C..; Jageneau A. H. M.; Demoen P. J. A.; Hermans B. K. F.; Van Daele G. H. P.; Schellekens K. H. L.; Van Der Eycken C. A. M.; Niemegeers C. J. E. Chemistry and Pharmacology of CNS Depressants Related to 4-(4-Hydroxy-4-Phenylpiperidino)Butyrophenone Part I-Synthesis and Screening Data in Mice. J. Med. Pharm. Chem. 1959, 1 (3), 281–297. 10.1021/jm50004a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divry P.; Bobon J.; Collard J. [R-1625: a new drug for the symptomatic treatment of psychomotor excitation]. Acta Neurol. Psychiatr. Belg. 1958, 58 (10), 878–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanner M. A.; Chappie T. A.; Dunaiskis A. R.; Fliri A. F.; Desai K. A.; Zorn S. H.; Jackson E. R.; Johnson C. G.; Morrone J. M.; Seymour P. A.; Majchrzak M. J.; Stephen Faraci W.; Collins J. L.; Duignan D. B.; Di Prete C. C.; Lee J. S.; Trozzi A. Synthesis, Sar and Pharmacology of CP-293,019: A Potent, Selective Dopamine D4 Receptor Antagonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8 (7), 725–730. 10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt J. O.; McCollum A. L.; Hurtado M. A.; Huseman E. D.; Jeffries D. E.; Temple K. J.; Plumley H. C.; Blobaum A. L.; Lindsley C. W.; Hopkins C. R. Synthesis and Characterization of a Series of Chiral Alkoxymethyl Morpholine Analogs as Dopamine Receptor 4 (D4R) Antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26 (10), 2481–2488. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.03.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino K. T.; Mashinson V.; Vadukoot A. K.; Hopkins C. R. Discovery and Characterization of Benzyloxy Piperidine Based Dopamine 4 Receptor Antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 61, 128615. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2022.128615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford B.; Lynch T.; Greene P. Risperidone in Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet 1994, 344 (8923), 681. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J. H.; Berman R. M.; Goetz C. G.; Factor S. A.; Ondo W. G.; Wojcieszek J.; Carson W. H.; Marcus R. N. Open-label Flexible-dose Pilot Study to Evaluate the Safety and Tolerability of Aripiprazole in Patients with Psychosis Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21 (12), 2078–2081. 10.1002/mds.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz A. L.; Kaufer D. I. Dementia in Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2011, 13 (3), 242–254. 10.1007/s11940-011-0121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubert I.; Guigoni C.; Håkansson K.; Li Q.; Dovero S.; Barthe N.; Bioulac B. H.; Gross C. E.; Fisone G.; Bloch B.; Bezard E. Increased D1 Dopamine Receptor Signaling in Levodopa-induced Dyskinesia. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57 (1), 17–26. 10.1002/ana.20296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmopil S.; Martín A. B.; De Diego I. R.; Ares S.; Moratalla R. Genetic Inactivation of Dopamine D1 but Not D2 Receptors Inhibits L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia and Histone Activation. Biol. Psychiatr. 2009, 66 (6), 603–613. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries D. E.; Witt J. O.; McCollum A. L.; Temple K. J.; Hurtado M. A.; Harp J. M.; Blobaum A. L.; Lindsley C. W.; Hopkins C. R. Discovery, Characterization and Biological Evaluation of a Novel (R)-4,4-Difluoropiperidine Scaffold as Dopamine Receptor 4 (D 4 R) Antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26 (23), 5757–5764. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry C. B.; Bubser M.; Jones C. K.; Hayes J. P.; Wepy J. A.; Locuson C. W.; Daniels J. S.; Lindsley C. W.; Hopkins C. R. Discovery and Characterization of ML398, a Potent and Selective Antagonist of the D4 Receptor with in Vivo Activity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5 (9), 1060–1064. 10.1021/ml500267c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boateng C. A.; Nilson A. N.; Placide R.; Pham M. L.; Jakobs F. M.; Boldizsar N.; McIntosh S.; Stallings L. S.; Korankyi I. V.; Kelshikar S.; Shah N.; Panasis D.; Muccilli A.; Ladik M.; Maslonka B.; McBride C.; Sanchez M. X.; Akca E.; Alkhatib M.; Saez J.; Nguyen C.; Kurtyan E.; DePierro J.; Crowthers R.; Brunt D.; Bonifazi A.; Newman A. H.; Rais R.; Slusher B. S.; Free R. B.; Sibley D. R.; Stewart K. D.; Wu C.; Hemby S. E.; Keck T. M. Pharmacology and Therapeutic Potential of Benzothiazole Analogues for Cocaine Use Disorder. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66 (17), 12141–12162. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Cao C.; He L.; Wang X.; Zhang X. C. Crystal Structure of Dopamine Receptor D4 Bound to the Subtype Selective Ligand, L745870. eLife 2019, 8, e48822 10.7554/eLife.48822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Wacker D.; Levit A.; Che T.; Betz R. M.; McCorvy J. D.; Venkatakrishnan A. J.; Huang X.-P.; Dror R. O.; Shoichet B. K.; Roth B. L. D4 Dopamine Receptor High-Resolution Structures Enable the Discovery of Selective Agonists. Science 2017, 358 (6361), 381–386. 10.1126/science.aan5468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. P.; Mendenhall J.; Meiler J. BCL::MolAlign: Three-Dimensional Small Molecule Alignment for Pharmacophore Mapping. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59 (2), 689–701. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carato P.; Graulich A.; Jensen N.; Roth B. L.; Liégeois J. F. Synthesis and in Vitro Binding Studies of Substituted Piperidine Naphthamides. Part II: Influence of the Substitution on the Benzyl Moiety on the Affinity for D2L, D4.2, and 5-HT2A Receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17 (6), 1570–1574. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J.-D.; Head-Gordon M. Long-Range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals with Damped Atom-Atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10 (44), 6615. 10.1039/b810189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaus M.; Cui Q.; Elstner M. DFTB3: Extension of the Self-Consistent-Charge Density-Functional Tight-Binding Method (SCC-DFTB). J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7 (4), 931–948. 10.1021/ct100684s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg J. G.; Grimme S. Accurate Modeling of Organic Molecular Crystals by Dispersion-Corrected Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB). J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5 (11), 1785–1789. 10.1021/jz500755u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering F.; Bikker J.; Humblet C. Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52 (21), 6752–6756. 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering F. Escape from Flatland 2: Complexity and Promiscuity. MedChemComm 2013, 4 (3), 515. 10.1039/c2md20347b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talele T. T. Opportunities for Tapping into Three-Dimensional Chemical Space through a Quaternary Carbon. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (22), 13291–13315. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiesinger K.; Dar’in D.; Proschak E.; Krasavin M. Spirocyclic Scaffolds in Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64 (1), 150–183. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino K. T.; Mashinson V.; Sharma M. K.; Chhonker Y. S.; Murry D. J.; Hopkins C. R. From Dopamine 4 to Sigma 1: Synthesis, SAR and Biological Characterization of a Piperidine Scaffold of Σ1 Modulators. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 244, 114840. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.