Abstract

Nebulized lidocaine may be a corticosteroid-sparing drug in human asthmatics, reducing airway resistance and peripheral blood eosinophilia. We hypothesized that inhaled lidocaine would be safe in healthy and experimentally asthmatic cats, diminishing airflow limitation and eosinophilic airway inflammation in the latter population. Healthy (n = 5) and experimentally asthmatic (n = 9) research cats were administered 2 weeks of nebulized lidocaine (2 mg/kg q8h) or placebo (saline) followed by a 2-week washout and crossover to the alternate treatment. Cats were anesthetized to measure the response to inhaled methacholine (MCh) after each treatment. Placebo and doubling doses of methacholine (0.0625–32.0000 mg/ml) were delivered and results were expressed as the concentration of MCh increasing baseline airway resistance by 200% (EC200Raw). Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed after each treatment and eosinophil numbers quantified. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) % eosinophils and EC200Raw within groups after each treatment were compared using a paired t-test (P <0.05 significant). No adverse effects were noted. In healthy cats, lidocaine did not significantly alter BALF eosinophilia or the EC200Raw. There was no difference in %BALF eosinophils in asthmatic cats treated with lidocaine (36±10%) or placebo (33 ± 6%). However, lidocaine increased the EC200Raw compared with placebo 10 ± 2 versus 5 ± 1 mg/ml; P = 0.043). Chronic nebulized lidocaine was well-tolerated in all cats, and lidocaine did not induce airway inflammation or airway hyper-responsiveness in healthy cats. Lidocaine decreased airway response to MCh in asthmatic cats without reducing airway eosinophilia, making it unsuitable for monotherapy. However, lidocaine may serve as a novel adjunctive therapy in feline asthmatics with beneficial effects on airflow obstruction.

Introduction

Feline asthma is a disorder of the lower airways that results in airway eosinophilia, airway hyper-responsiveness and airway remodeling. 1 Currently, treatment focuses on ameliorating clinical signs relating to inflammation and airflow limitation with oral or inhaled glucocorticoids (GC) and bronchodilators. These drugs may be contraindicated with certain concurrent diseases (especially cardiac disease) or side effects may limit their use. As a result, there is a demand for novel therapeutics that reduce airway inflammation and airflow obstruction with few adverse effects. Lidocaine, commonly used as a local anesthetic and anti-arrhythmic agent, has gained some attention as a potential steroid-sparing treatment for asthma in humans. To our knowledge, the safety and efficacy of nebulized lidocaine in healthy or asthmatic cats has not been investigated.

Topical and inhaled lidocaine is commonly used as a means of local anesthesia for patients undergoing bronchoscopy.2,3 In an in vitro study of eosinophil survival in human asthmatics undergoing bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), lidocaine present in BAL fluid was serendipitously discovered to inhibit eosinophil-active cytokines. 4 Consequently, interest in lidocaine as a novel anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of asthma developed. An initial study of nebulized lidocaine in humans with severe glucocorticoid-dependent asthma found 17/20 patients were able to discontinue or reduce GC use while maintaining control of asthma symptoms. 5 A subsequent study demonstrated nebulized lidocaine allowed for corticosteroid withdrawal without increases in peripheral blood eosinophilia (a surrogate marker of inflammation in asthmatics) while concurrently improving pulmonary function in adults. 6 Another study in children confirmed the benefit of inhaled lidocaine’s GC-sparing effects in children with severe asthma. 7

The purpose of the present study in healthy and experimentally-asthmatic cats was to administer nebulized lidocaine and evaluate the safety of, and effects on, airway inflammation and hyper-responsiveness. We hypothesized that inhaled lidocaine would be well tolerated in healthy and experimentally asthmatic cats, and reduce both airflow limitation and eosinophilic airway inflammation in the latter population.

Materials and methods

Cats

Healthy control (n = 5; two females and three males) and experimentally-induced asthmatic (n = 9; six females and three males) research cats, all intact, were either bred from a high-responder asthmatic cat research colony (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA) or were obtained from an outside vendor (Liberty Research, Waverly, NY, USA). This study was approved by the University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee. Cats were cared for in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Induction of experimental asthma

Prior to induction of an asthmatic phenotype, all cats were tested by performance of intradermal skin testing to confirm they had not previously been sensitized to Bermuda grass allergen (BGA). In addition, collection and analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was performed to ensure they did not have pre-existing eosinophilic airway inflammation. Cats were sensitized and challenged as described previously. 8 Cats received an aerosol challenge of BGA 24 h prior to each pulmonary mechanics measurement.

Lidocaine treatment

All cats (healthy controls and experimentally-induced asthmatics) received aerosolized treatments of either lidocaine (Hospira Worldwide; 4% without preservatives diluted to 2% and administered at a dose of 2 mg/kg q8h) or placebo (identical volume as lidocaine) using a vibrating mesh nebulizer (Omron Healthcare, model NE-U22V). Treatments were delivered for 2 weeks prior to pulmonary mechanics testing and collection of BALF; the last dose was administered the evening before pulmonary mechanics measurements. Each cat underwent a 2-week washout period and crossover to the alternate treatment followed by the aforementioned evaluations.

Pulmonary mechanics measurement

Gas flow and airway pressure was measured and pulmonary resistance calculated using a commercially-available critical care ventilator (Engstrom Carestation; GE Healthcare). Cats were sedated with ketamine (30.0 mg IV), and anesthesia was induced with propofol (6.0 mg/kg IV) and maintained with a continuous infusion of the same (0.2 mg/kg/min). Intermittent boluses of propofol were administered (0.5–1.0 mg/kg IV) as needed to maintain an appropriate plane of anesthesia and absence of spontaneous respiratory activity. To standardize resistance contributions from endotracheal tubes (ETT), all cats were intubated with 4 mm internal diameter, 14 cm-long cuffed ETT. A heated pneumotachograph was placed in line at the oral end of the ETT to measure gas flow. Animals were ventilated mechanically using a volume-controlled ventilation mode (tidal volume = 10 ml/kg, respiratory rate = 10 breaths/min, inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio = 1:3, inspired oxygen = 40%). After a 5-min equilibration period, sterile placebo was delivered via nebulization (Aeroneb Pro; Aerogen). Gas flow and pressure measurements were obtained, and airway resistance calculated for 4 mins (baseline). The ventilator was recalibrated between subjects.

Bronchoprovocation challenge

Methacholine (MCh) challenge was performed by delivering doubling concentrations of the drug (0.0625–32.0000 mg/ml) through the in-line nebulizer for 30 s followed by 4 mins of data collection. Bronchoprovocation was terminated when displayed Raw was increased 200% above baseline. Data were expressed as the concentration of MCh that increased Raw by 200% (EC200Raw), as determined by linear interpolation of the log–log plot of the dose response curve.

Collection and analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

BALF was collected in a blind fashion as described previously and after MCh bronchoprovocation. 1 All samples were placed on ice during the time between collection and analysis (within 2 h). Samples were prepared by cytocentrifugation (Shandon Cytospin 4; ThermoElectron) for cytological evaluation and 200 nucleated cell differential counts.

Statistical analysis

A paired t-test was used to evaluate the difference between BALF eosinophil percentage and the EC200Raw in cats treated with aerosolized lidocaine compared to aerosolized placebo within groups (healthy and asthmatic). A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed to ensure normality. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Safety

The initial dose of inhaled lidocaine in the first cat was administered at a concentration of 4% and induced hypersalivation. After the concentration was reduced to a 2% solution, no overt adverse events were noted during or immediately following aerosolized lidocaine treatments in any cat.

Airway hyper-responsiveness

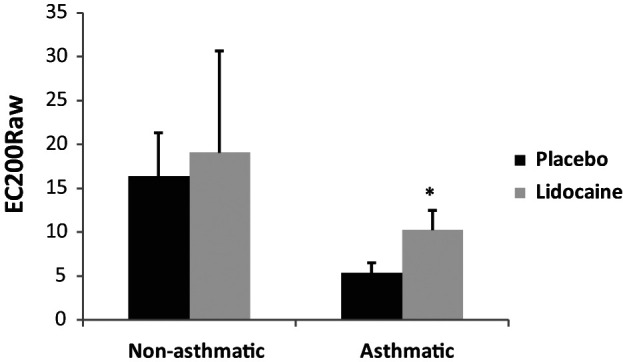

In healthy research cats, the group mean ± SEM EC200Raw was not different between treatments (P = 0.874; Figure 1). In experimentally-asthmatic cats, inhaled lidocaine resulted in an increase in the EC200Raw when compared with placebo (P = 0.043; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the EC200Raw as assessed during bronchoprovocation with methacholine challenge in healthy, non-asthmatic and experimentally-asthmatic cats treated with lidocaine and placebo. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

*EC200Raw was significantly higher in lidocaine treatment asthmatic cats when compared with placebo (P = 0.043). There was no significant difference in the EC200Raw for non-asthmatic cats treated with lidocaine and placebo

Airway eosinophilia

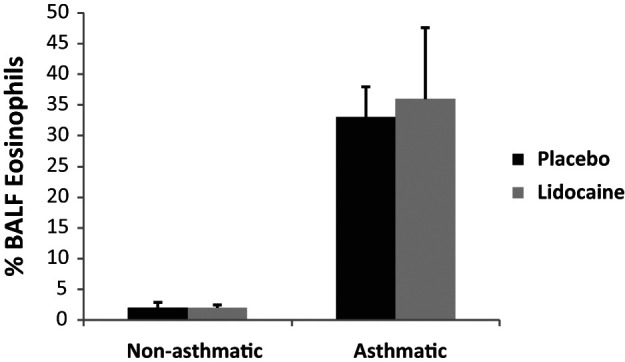

There was no difference in the group mean ± SEM percentage of BALF eosinophils in asthmatic cats (P = 0.800) and healthy, non-asthmatic cats (P = 0.704) when comparing treatment with inhaled lidocaine and placebo (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the % bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) eosinophils in healthy, non-asthmatic and experimentally-asthmatic cats treated with lidocaine and placebo. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. There was no significant difference in the % BALF eosinophils between treatments for non-asthmatic and asthmatic cats

Discussion

In experimentally-asthmatic cats, inhaled lidocaine significantly blunted airway resistance in response to bronchoprovocation by MCh. Targeting airflow limitation is an important therapeutic goal in asthma as it contributes to clinical signs. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate inhaled lidocaine in cats and provides pilot data for controlled clinical trials to evaluate this drugs’ efficacy on blunting airflow limitation in cats with naturally-occurring asthma.

The results of this study parallel findings in human asthmatics that chronic nebulized lidocaine results in an improvement in airflow limitation. 6 The ability of lidocaine to improve airflow limitation makes it an appealing therapeutic option. Current bronchodilator therapy in feline asthma consists of b2 agonists (eg, albuterol and terbutaline) and methylxanthine agents (eg, theophylline and aminophylline). While both classes of bronchodilators are effective at reducing bronchospasm, the potential adverse cardiac and gastrointestinal effects, and frequency of oral administration are limiting in some patients. Although inhaled albuterol may provide an alternative for owners that are unable to administer daily oral medications, evidence suggests that regular use of inhaled racemic albuterol induces airway inflammation, making it unsuitable for maintenance therapy. 9 Lidocaine provides an alternative to conventional bronchodilators in that it is relatively inexpensive, may be used in cats with certain types of cardiac disease and relieves airflow limitation via a different pathway. Inhaled lidocaine results in relatively low plasma concentrations, but higher airway concentrations, with speculated mechanisms of bronchospasm attenuation theorized as neural blockade of the vagal reflex pathways or direct reduction of bronchial smooth muscle tone.10,11 In humans, the former mechanism seems more plausible as inhaled lidocaine did not attenuate MCh-induced bronchoconstriction, but did attenuate bronchoconstriction induced by histamine. 12 In the asthmatic cats of this study, inhaled lidocaine decreased the airway response to MCh challenge, suggesting there may be a direct effect of lidocaine on smooth muscle in this species. The present study utilized ventilator acquired mechanics as a method for evaluating airway resistance, and, therefore, the effects of inhaled lidocaine on tissue resistance and bronchomotor tone were not evaluated. The ventilator was used in neonatal mode in which a heated pneumotachograph is placed at the end of the endotracheal tube, interposed between the patient and the ventilator circuitry; this allows improved mechanics measurements compared with internal transducers. Additionally, the ventilator has a resolution of 1 cmH2O, a repeatability ± 1 cmH2O, an accuracy of ± 2 cmH2O and a range of −20 to 120 cmH2O.

Of importance, the current study evaluated effects of ‘chronic’ (three times daily for 2 weeks) administration of nebulized lidocaine, which may lead to a different outcome on airway hyper-responsiveness assessment than a single dose. In human asthmatics, multiple studies have suggested that inhaled lidocaine may lead to an initial bronchoconstriction (the clinical significance of which is debatable) followed by attenuation of reflex bronchoconstriction after a variety of different types of bronchoprovocants.10,13 One of these studies documented a statistically significant decrease in the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1; a direct measure of airflow obstruction) of 6.7%; however, they also commented that a clinically relevant change is a decrease of FEV1 on the order of 15–17%. 10 In contrast, lidocaine acted synergistically with b2 agonist to attenuate reflex bronchoconstriction induced by intubation. 11 While none of the asthmatic cats in this study showed evidence of clinically significant bronchoconstriction after inhaled lidocaine administration (ie, cough, wheeze, respiratory distress), clinical trials in cats with naturally-developing feline asthma are recommended prior to using inhaled lidocaine. This combination should also be considered in future studies in asthmatic cats.

While improvement of pulmonary mechanics is important, it would be ideal to have a therapy that would also diminish airway eosinophilia, another hallmark feature of asthma. When human peripheral eosinophils were stimulated in vitro with interleukin (IL)-3, IL-5 and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, superoxide production was decreased in the presence of lidocaine, supporting the role of lidocaine as a potential anti-inflammatory agent. 14 Additionally, in vitro evaluation of lidocaine on stimulated T lymphocytes resulted in reduced IL-5 production. 15 In the current study, inhaled lidocaine did not reduce BALF eosinophilia in experimentally asthmatic cats. We did not determine if the pro-inflammatory activity of eosinophils in treated cats was altered. It is unclear if the nebulized lidocaine failed to dampen airway eosinophilia in cats in the present study because of dose, frequency and/or duration of therapy. The dose of inhaled lidocaine was extrapolated from aforementioned human studies.6,7 The frequency of administration of lidocaine (three times daily) was chosen in an effort to mimic realistic therapeutic frequency in clinical feline patients. Assessment of the pharmacokinetics of inhaled lidocaine would be beneficial in determining the optimal dosing strategy.

Intravenous lidocaine has potential epileptogenic and arrhythmogenic effects in cats. 16 In humans, the inhaled route of use was not associated with signs of lidocaine toxicity; in fact, very large quantities of nebulized lidocaine (well over 400 mg or 5 ml/kg) need to be administered to result in toxic serum concentrations in humans. 6 Importantly, inhaled lidocaine (2 mg/kg q8h for 2 weeks) was well-tolerated in healthy control and experimentally-asthmatic cats with no overt evidence of gastrointestinal, cardiac or neurological clinical signs. It is unknown if inhaled lidocaine induced subclinical arrhythmias. The sole adverse reaction was hypersalivation in a single cat (the first one tested), which resolved after we decreased the concentration of the lidocaine from a 4% solution to a 2% solution. In humans, lidocaine is reported to have a bitter taste and may result in nausea, dizziness and headaches. The hypersalivation observed was presumed to be due to the bitter taste associated with nebulized lidocaine. Topical lidocaine has been reported to cause oxidative hemoglobin injury, resulting in methemoglobinemia in humans undergoing fiberoptic bronchoscopy. 17 We did not evaluate for clinicopathologic abnormalities (eg, evidence of oxidative injury to red blood cells) in the present study.

Conclusions

Nebulized lidocaine reduced airway hyper-responsiveness in response to MCh challenge in experimentally-asthmatic cats. After appropriate clinical trials in pet cats with spontaneous asthma, lidocaine may offer an alternative to current short-acting bronchodilators. While effects to diminish airway hyper-responsiveness are promising, control of airway inflammation is an essential component of both short- and long-term management of asthma. Nebulized lidocaine at the dose and frequency used in the present study did not blunt airway eosinophilia, and, therefore, cannot be recommended as long-term monotherapy for feline asthma. Additional questions need to be answered prior to routine use in cats with naturally-developing feline asthma, including the optimal dose and/or frequency of nebulized lidocaine administration, whether there is a risk of initial clinically significant bronchoconstriction, which might be prevented by b2 agonist use, and if there is synergy with other bronchodilators. Studies evaluating nebulized lidocaine in combination with medications that have been proven to blunt airway eosinophilia (eg, glucocorticoids) should also be considered. 18

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Chee-Hoon Chang and Hong Liu for their technical support.

Footnotes

Funding: The ventilator used in this study was provided by the Cisco Fund for Immunologic Research.

The authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Accepted: 8 January 2013

References

- 1. Norris Reinero CR, Decile KC, Berghaus RD, et al. An experimental model of allergic asthma in cats sensitized to house dust mite or bermuda grass allergen. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2004; 135: 117–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antoniades N, Worsnop C. Topical lidocaine through the bronchoscope reduces cough rate during bronchoscopy. Respirology 2009; 14: 873–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gjonaj ST, Lowenthal DB, Dozor AJ. Nebulized lidocaine administered to infants and children undergoing flexible bronchoscopy. Chest 1997; 112: 1665–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ohnishi T, Kita H, Mayeno AN, et al. Lidocaine in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) is an inhibitor of eosinophil-active cytokines. Clin Exp Immunol 1996; 104: 325–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hunt LW, Swedlund HA, Gleich GJ. Effect of nebulized lidocaine on severe glucocorticoid-dependent asthma. Mayo Clinic Proc 1996; 71: 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hunt LW, Frigas E, Butterfield JH, et al. Treatment of asthma with nebulized lidocaine: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Decco ML, Neeno TA, Hunt LW, et al. Nebulized lidocaine in the treatment of severe asthma in children: a pilot study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1999; 82: 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reinero CR, Lee-Fowler TM, Dodam JR, et al. Endotracheal nebulization of N-acetylcysteine increases airway resistance in cats with experimental asthma. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reinero CR, Delgado C, Spinka C, et al. Enantiomer-specific effects of albuterol on airway inflammation in healthy and asthmatic cats. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2009; 150: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Groeben H, Silvanus MT, Beste M, et al. Both intravenous and inhaled lidocaine attenuate reflex bronchochonstriction but at different plasma concentrations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 159: 530–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Groeben H, Schlicht M, Stieglitz S, et al. Both local anesthetics and salbutamol pretreatment affect reflex bronchoconstriction in volunteers with asthma undergoing awake fiberoptic intubation. Anesthesiology 2002; 97: 1445–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Groeben H, Peters J. Lidocaine exerts its effect on induced bronchospasm by mitigating reflexes, rather than by attenuation of smooth muscle contraction. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2007; 51: 359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McAlpine LG, Thomson NC. Lidocaine-induced bronchoconstriction in asthmatic patients. Relation to histamine airway responsiveness and effect of preservative. Chest 1989; 96: 1012–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Okada S, Hagan JB, Kato M, et al. Lidocaine and its analogues inhibit IL-5-mediated survival and activation of human eosinophils. J Immuno 1998; 160; 4010–4017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tanaka A, Minoguchi K, Oda N, et al. Inhibitory effect of lidocaine on T cells from patients with allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 109: 485–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chadwick H. Toxicity and resuscitation in lido- or bupivacaine-infused cats. Anesthesiology 1985; 63: 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. De S. Assessment of severity of methaemoglobinemia following fiberoptic bronchoscopy with lidocaine. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2011; 53: 211–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leemans J, Kirschvink N, Clercx C, et al. Effect of short-term oral and inhaled corticosteroids on airway inflammation and responsiveness in a feline acute asthma model. Vet J 2012; 192: 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]