Abstract

We report the generation of a nonbenzenoid polycyclic conjugated hydrocarbon, which consists of a biphenyl moiety substituted by indenyl units at the 4,4′ positions, on ultrathin sodium chloride films by tip-induced chemistry. Single-molecule characterization by scanning tunneling and atomic force microscopy reveals an open-shell biradical ground state with a peculiar electronic configuration wherein the singly occupied molecular orbitals (SOMOs) are lower in energy than the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO).

Keywords: scanning tunneling microscopy, atomic force microscopy, on-surface synthesis, atom manipulation, open-shell molecules, organic radicals, polycyclic conjugated hydrocarbons

There are currently immense interest and progress in organic radicals and, in particular, in open-shell polycyclic conjugated hydrocarbons. This is driven by both advancements in on-surface chemistry for synthesis and stabilization of reactive species1 and the fundamental insights that organic radicals provide into chemical reactions, many-body nature of electronic wave functions, and theoretical models in quantum magnetism, with implications for spintronic and optoelectronic technologies.2−4 In a molecular orbital picture, a closed-shell molecule (Figure 1a) is represented by a series of doubly occupied molecular orbitals leading up to the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and a series of empty molecular orbitals beginning with the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). HOMO and LUMO are the frontier molecular orbitals, which to a great extent govern the chemical reactivity, electronic transport, and low-energy optical transitions of a molecule. Conversely, for the majority of open-shell molecules (for simplicity, we first consider a monoradical; Figure 1b), the frontier molecular orbital is a singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO),5,6 whose one spin level (spin up or spin down) is occupied, and the corresponding opposite-spin level, referred to as SUMO, is empty. Interestingly, there have been reports on radicals with an unusual electronic configuration, where the energy of the SOMO lies below one or more doubly occupied molecular orbitals (Figure 1c,d).7 This phenomenon is termed SOMO-HOMO inversion (SHI). SHI has been associated with enhanced radical stability, for example, improved photostability and enhanced quantum yield of luminescent radicals,8 and generation of high-spin states upon radical oxidation that could be exploited for the development of organic ferromagnetic materials.9 Furthermore, chiral conjugated SHI molecules are attracting interest given the potential of designing functionalities such as circularly polarized luminescence and chirality-induced spin selectivity.10 SHI radicals have also been utilized as key intermediates in chemical reactions, such as in amination of imidates and amidines,11 and in photocatalytic allylation.12

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the electronic configuration of (a) a closed-shell molecule, (b) an open-shell molecule without SHI, (c) an open-shell molecule with partial SHI, wherein the energy of the SOMO lies between the spin-up and spin-down HOMO levels, and (d) an open-shell molecule with SHI, wherein the energy of the SOMO is lower than both the spin levels of HOMO.

The topic of SHI in organic radicals dates back to the 1987 study of Awaga et al., who performed spin-unrestricted calculations on the galvinoxyl radical and demonstrated the existence of partial SHI in the molecule (Figure 1c).13 Experimentally, the first organic radical exhibiting SHI was a tetrathiafulvalene derivative substituted with imino pyrolidine and piperidine-1-oxyl, synthesized by Sugimoto et al. in 1993.14 Since then, SHI has been experimentally found in a number of molecular systems, such as aromatic heterocycles substituted with aminoxyl radicals,15−19 nitroxyl metalladithiolates,20,21 carboxy-tetrathiafulvalene crystals,22 and metalloporphyrins and metallophthalocyanines.23 More recently, SHI has also been experimentally shown to occur in distonic radical ions,24,25 sulfur- and nitrogen-containing helicene-based neutral radicals and radical ions,26,27 carbazole-based radical ions,10,28 triarylmethyl-radical-based donor–acceptor frameworks,8,29 spiro-conjugated donor–acceptor charged frameworks,30 and spiro-fused diarylaminyl radicals.31 Theoretically, SHI has been shown to occur in biologically important radicals such as singly oxidized nucleobases and DNA base pairs,32,33 singly reduced radicals of diatomic molecules such as O2 and BN,33 triplet carbene-based frameworks,34 triplet cyclopentane-1,3-diyl-based diradicals,35 oxidized azulene derivatives,36 donor–acceptor conjugated polymers,37 napthalene diimides substituted with pyridines,38 helical π-systems,39 triplet polycyclic hydrocarbons,40 and porphyrin oligomers.41 Abella et al. conducted a detailed theoretical study of the mechanism of SHI in organic radicals, which were conceptually generated by one-electron oxidation of the corresponding closed-shell parent compounds that contained an additional electron.38 Their analysis revealed three key criteria for SHI to occur. First, a strongly localized HOMO of the closed-shell parent results in a strong self-Coulomb repulsion, that is, repulsion between electrons in the HOMO. Upon ionization, relieving of the self-Coulomb repulsion leads to a notable drop in the energy of this orbital. Second, spatially disjoint HOMO and HOMO-1 of the closed-shell parent results in a weak Coulomb repulsion between the two orbitals, and consequently, the energy of the latter orbital drops far less upon ionization. Third, a small gap between HOMO and HOMO-1 of the closed-shell parent promotes this energetic crossover upon ionization.

To date, the experimental existence of SHI has been established through bulk spectroscopic measurements, such as absorption and photoelectron spectroscopies, cyclic voltammetry, and electron spin resonance. However, SHI has not been detected at the single-molecule level, and SHI has never been observed in a neutral polycyclic conjugated hydrocarbon. Here, we report the generation of a nonbenzenoid open-shell polycyclic conjugated hydrocarbon 1 (C30H20; Figure 2a), which exhibits SHI. Compound 1 is structurally related to Chichibabin’s hydrocarbon (C38H28; Figure 2b),42,43 where the terminal diphenylmethylene substituents in Chichibabin’s hydrocarbon are replaced by indenyl substituents in 1. Compared to their respective closed-shell structures, 1 and Chichibabin’s hydrocarbon gain four and two aromatic sextets in their open-shell structures, respectively. Therefore, a larger biradical open-shell character is expected for 1 compared to Chichibabin’s hydrocarbon.

Figure 2.

Structural characterization of 1. Closed-shell Kekulé (top) and open-shell non-Kekulé (bottom) resonance structures of (a) 1 and (b) Chichibabin’s hydrocarbon. (c) Scheme of on-surface generation of 1 through the voltage-pulse-induced dehydrogenation of 2H-1. Compound 1H-1 denotes the intermediate monoradical species after removal of one hydrogen atom from 2H-1. Gray filled rings denote aromatic π-sextets. (d) In-gap STM image of 1 (V = 0.2 V and I = 0.5 pA; V and I denote the bias voltage and tunneling current, respectively). Δh denotes the tip height. The species at the bottom-right of the scan frame is a 2H-1 molecule. (e) Corresponding AFM image of 1. Δf and Δz denote the frequency shift and the tip-height offset with respect to the STM set point, respectively. Positive and negative values of Δz denote tip approach and retraction from the STM set point, respectively. Here, 1 is changing its adsorption site under the influence of the tip during scanning, which causes the apparent bisection of the molecule along its long axis. (f) AFM image and (g) the corresponding Laplace-filtered version of the same molecule as in (e), with its adsorption orientation changed by ∼20° (see also Figure S10). a.u. denotes arbitrary units. The movement of 1 is now hindered by the 2H-1 species at the bottom. The two bright features at the center of 1 that are indicated with arrows in (g) correspond to the strongly tilted hexagonal rings of the biphenyl moiety. The indenyl units also tilt, but to a lesser degree. STM set point for AFM images: V = 0.2 V and I = 0.5 pA on bilayer NaCl.

Results and Discussion

Generation and Structural Characterization of 1

Compound 1 was generated from the stable dihydro precursor 2H-1 (C30H22; Figure 2c), which was synthesized in solution by double Suzuki coupling (see the Supporting Information). Single molecules of 2H-1 were deposited on a single-crystal Au(111) surface that was partially covered by two-monolayers-thick (denoted bilayer) NaCl films (Figures S1–S3) and housed inside a combined scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) apparatus operating under ultrahigh vacuum and at a temperature of 5 K. Voltage pulses ranging between 5.8 and 6.4 V were applied to individual 2H-1 molecules by the tip of the STM/AFM system, resulting in the homolytic cleavage of the C(sp3)-H bond at each of the pentagonal rings, thereby leading to the generation of 1 via the singly dehydrogenated intermediate 1H-1 (Figure 2c). The generation of 1 was always achieved in a sequential manner, with separate voltage pulses applied, each dissociating one hydrogen. The yield for a C(sp3)-H bond cleavage with such pulses was ∼30%, for both the first dehydrogenation yielding 1H-1 and the second dehydrogenation yielding 1. In unsuccessful events, the molecule was displaced on the surface but stayed intact; that is, no hydrogen was dissociated. The molecule was always displaced during voltage pulses, rendering a detailed statistical analysis of the dissociation process challenging. In the main text, we focus on the characterization of 1 on bilayer NaCl/Au(111). For the generation and characterization of 1 on Au(111), see Figure S4. Figure 2d,e presents the STM and AFM images of 1 generated after a voltage-pulse sequence. The images reveal an apparent bisection of 1 along the long molecular axis, which results from the movement of 1 between different adsorption sites under the influence of the microscope tip.5 The adsorption of 1 can be stabilized in the vicinity of a defect, adsorbate, or step edge. Figure 2f shows the AFM image of the same molecule after its lower part moved adjacent to a 2H-1 species, thereby leading to stable adsorption. The corresponding Laplace-filtered AFM image (Figure 2g) resolves the terminal indenyl units, along with two bright features (that is, with a higher frequency shift due to stronger repulsive forces) in the central part that correspond to the strongly tilted hexagonal rings of the biphenyl moiety.44

Electronic Characterization of 1

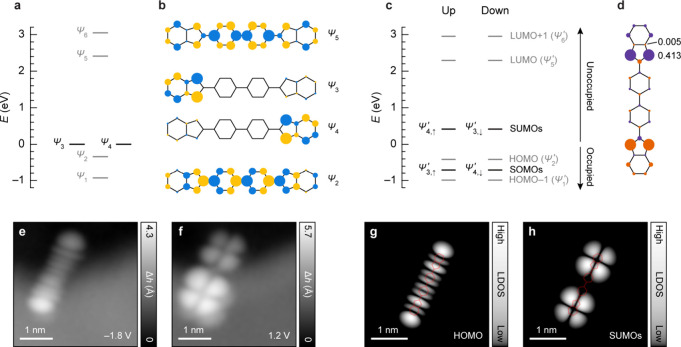

To describe the electronic structure of 1, we start by performing nearest-neighbor tight-binding calculations. Our tight-binding results are supported by density functional theory calculations shown in Figure S5. Figure 3a shows the tight-binding energy spectrum of 1, where the salient features correspond to a pair of degenerate states labeled Ψ3 and Ψ4, whose wave functions are strongly localized on either of the indenyl units and the states Ψ2 and Ψ5 that are delocalized over the molecular framework (Figure 3b). Of note is the close energetic proximity of Ψ2 to Ψ3/Ψ4 and a much larger separation between Ψ5 and Ψ3/Ψ4. To describe the formation of local magnetic moments and magnetic exchange in 1, we include electronic correlations via the Hubbard approximation, where an on-site Coulomb repulsion term is included in the tight-binding Hamiltonian, that is, the mean-field Hubbard model. Previous works have shown the Hubbard approximation to be consistent with spin-polarized density functional theory calculations.45,46 The mean-field Hubbard solution leads to spin polarization of 1, with nearly degenerate open-shell singlet and triplet states (Figure S6), as also predicted by our density functional theory calculations (Figure S5). Figure 3c shows the mean-field Hubbard energy spectrum of 1 in the open-shell singlet state (we note that our experimental results are also consistent with the triplet state of 1, see Figure S6), with the corresponding spin polarization plot shown in Figure 3d. We denote the mean-field Hubbard states as Ψ′1–Ψ′6, which are derived from the corresponding tight-binding states Ψ1–Ψ6. While there are negligible changes in the energies of Ψ′2 and Ψ′5 compared to the tight-binding states Ψ2 and Ψ5, respectively, the degeneracy of Ψ3 and Ψ4 is lifted by spin polarization, along with the opening of a Hubbard gap in the energy spectrum. At this stage, SHI is already established in 1. The energies of the SOMOs, that is, the occupied spin levels of Ψ′3 and Ψ′4, are lowered to the extent that these states shift below Ψ′2, which is the HOMO. This is likely aided by the strongly localized character of Ψ3 and Ψ4 (Figure 3b) that promotes substantial lowering of the energy of these states upon spin polarization, along with the previously noted small gap between Ψ2 and Ψ3/Ψ4 (Figure 3a) that promotes such a crossover. Concurrently, the gap between Ψ5 and Ψ3/Ψ4 is large enough that the SUMOs, that is, the unoccupied spin levels of Ψ′3 and Ψ′4, remain as the frontier unoccupied states upon spin polarization. The existence of SHI in 1 is experimentally confirmed by STM imaging at ionic resonances. The positive (negative) ion resonance denotes transition between the neutral and cationic (anionic) states of a molecule, which corresponds to electron detachment from (attachment to) the occupied (unoccupied) frontier molecular orbitals. STM images of 1 acquired at the positive (Figure 3e) and negative (Figure 3f) ion resonances show orbital densities that concur with the calculated local density of states maps of HOMO (Figure 3g) and SUMOs (Figure 3h), respectively. The observation of HOMO and SUMOs as the frontier orbitals thus proves SHI in 1. SHI is also observed for the monoradical species 1H-1 (Figures S7–S9). Whereas SHI manifests in 1 in the form of two energetically degenerate SOMOs that lie below the HOMO, in 1H-1, a single SOMO lies below the HOMO. The latter scenario, schematically depicted in Figure 1, has been previously observed for several molecular systems.

Figure 3.

Electronic characterization of 1. (a) Tight-binding energy spectrum of 1. Zero of the energy axis is set to match the energy of degenerate states Ψ3 and Ψ4. The nearest-neighbor hopping parameter is 2.7 eV. (b) Tight-binding wave functions of Ψ2, Ψ3, Ψ4, and Ψ5. Size and color of the circles denote the amplitude and phase of the wave functions. (c) Mean-field Hubbard energy spectrum of 1 in the open-shell singlet state. States Ψ′1–Ψ′6 are derived from the corresponding tight-binding states Ψ1–Ψ6. Zero of the energy axis is set to lie between the HOMO and SUMOs. States above and below zero energy are unoccupied and occupied, respectively. The on-site Coulomb repulsion is ∼4 eV. (d) Spin-polarization plot of 1 in the open-shell singlet state, expressed as the difference in mean populations of spin-up and spin-down electrons at each carbon atom. Size and color of the circles denote the value and sign of spin polarization, respectively. The numbers denote absolute values of spin polarization. (e, f) STM images of 1, immobilized at a gold step edge overgrown by NaCl, acquired at the positive (e) and negative (f) ion resonances (I = 0.1 pA). (g, h) Constant-height mean-field Hubbard local density of states (LDOS) maps of HOMO (|Ψ′2, ↑|2 + |Ψ′2, ↓|2; g) and SUMOs (|Ψ′4, ↑|2 + |Ψ′3, ↓|2; h) of 1, calculated at a height of 5.6 Å above the molecular plane and shown in a logarithmic color scale. AFM image of the molecule in (e) and (f) is shown in Figure S11.

Conclusions

We generated a nonbenzenoid polycyclic conjugated hydrocarbon 1 on bilayer NaCl/Au(111) by scanning-probe-based atom manipulation. Compound 1 consists of a biphenyl moiety substituted by indenyl units at the 4,4′ positions. Structural characterization of 1 by AFM reveals a nonplanar adsorption conformation with strongly tilted hexagonal rings of the biphenyl moiety. Electronic characterization of 1 by STM-based orbital-density imaging reveals an open-shell biradical ground state, with manifestation of the unusual phenomenon of SHI, wherein the SOMOs are lower in energy than the HOMO, which is in contrast to the majority of reported open-shell molecules. The demonstrated ability to detect SHI at the single-molecule level facilitates future experiments and applications of inducing or switching (on and off) SHI by changes in the adsorption site47 or molecular conformation,48 through proximity to adsorbates,49 or by means of external fields.50

Methods

Sample Preparation and Scanning Probe Microscopy Measurements

The Au(111) surface was prepared by multiple cycles of sputtering with Ne+ ions and annealing up to 800 K. NaCl was thermally evaporated on the Au(111) surface held at 323 K, which resulted in the growth of predominantly bilayer (100)-terminated islands, with a minority of third-layer islands. Submonolayer coverage of 2H-1 on the surface was obtained by flashing an oxidized silicon wafer containing 2H-1 molecules in front of the cold sample in the microscope. Carbon monoxide molecules for tip functionalization were dosed from the gas phase on the cold sample. STM and AFM measurements were performed in a home-built system operating at base pressures below 1 × 10–10 mbar and a base temperature of 5 K. Bias voltages were applied to the sample with respect to the tip. Unless otherwise mentioned, all STM and AFM measurements were performed with carbon-monoxide-functionalized tips. AFM measurements were performed in noncontact mode with a qPlus sensor.51 The sensor was operated in frequency-modulation mode52 with a constant oscillation amplitude of 0.5 Å. Unless noted otherwise, STM measurements were performed in constant-current mode, and AFM measurements were performed in constant-height mode with V = 0 V. STM and AFM images were postprocessed using Gaussian low-pass filters.

Tight-Binding Calculations

Tight-binding and mean-field Hubbard calculations were performed by numerically solving the following mean-field Hubbard Hamiltonian with nearest-neighbor hopping

| 1 |

Here,  and cj,σ denote the spin selective (σ ∈ { ↑,

↓ } with σ̅ ∈ { ↓, ↑ }) creation

and annihilation operator at neighboring sites i and j, t = 2.7 eV is the nearest-neighbor hopping

parameter, U is the on-site Coulomb repulsion, and ni,σ and ⟨ni,σ⟩ denote the

number operator and mean occupation number at site i, respectively. Orbital electron densities, ρ, of the nth eigenstate with energy En have been simulated from the corresponding

state vector an,i,σ by

and cj,σ denote the spin selective (σ ∈ { ↑,

↓ } with σ̅ ∈ { ↓, ↑ }) creation

and annihilation operator at neighboring sites i and j, t = 2.7 eV is the nearest-neighbor hopping

parameter, U is the on-site Coulomb repulsion, and ni,σ and ⟨ni,σ⟩ denote the

number operator and mean occupation number at site i, respectively. Orbital electron densities, ρ, of the nth eigenstate with energy En have been simulated from the corresponding

state vector an,i,σ by

| 2 |

where ϕ2pz denotes the Slater 2pz orbital for carbon.

Density Functional Theory Calculations

Density functional theory calculations were performed using the FHI-aims code.53 Closed-shell, open-shell singlet, and triplet states of 1 were independently investigated in the gas phase, wherein the geometry of each spin state was optimized. The B3LYP exchange-correlation functional, using the Vosko-Wilk-Nusair local-density approximation as implemented in the FHI-aims code, was employed.54 We used the van der Waals scheme by Tkatchenko and Scheffler.55 The convergence criteria for all calculations were set to 1 × 10–3 eV/Å for the total forces and 1 × 10–5 eV for the total energies. Open-shell calculations were performed in the spin-polarized (unrestricted) framework and closed-shell calculations were performed in the non-spin polarized (restricted) framework. The basis defaults were set to “really tight” for all elements. For open-shell calculations, an initial spin moment was placed at the two apical carbon atoms of each of the pentagonal rings.

Acknowledgments

This study has received funding from the European Union project SPRING (grant number 863098), the European Research Council Synergy grant MolDAM (grant number 951519), the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación (grant number PID2022-140845OB-C62), Xunta de Galicia (Centro de Investigación de Galicia accreditation 2019–2022, grant number ED431G 2019/03), the European Regional Development Fund, and the KAUST Office of Sponsored Research (grant number OSRCRG2022-503). Computational support from the Supercomputing Laboratory at KAUST is acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.4c03257.

Scanning probe microscopy measurements and calculations (Figures S1–S11, Tables S1–S3), solution synthesis of 2H-1 (Scheme S1) and mass spectrometry of 2H-1 (Figures S12 and S13) (DOCX)

Author Contributions

S.M. and L.G. performed scanning probe microscopy measurements. S.M. performed tight-binding calculations. S.F. performed density functional theory calculations. M.V-.V. and D.P. performed solution synthesis of 2H-1 and mass spectrometry measurements. S.M. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and edited the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

A previous version of this manuscript has been deposited on a preprint server.56

Supplementary Material

References

- Clair S.; de Oteyza D. G. Controlling a Chemical Coupling Reaction on a Surface: Tools and Strategies for On-Surface Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119 (7), 4717–4776. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuyver T.; Chen B.; Zeng T.; Geerlings P.; De Proft F.; Hoffmann R. Do Diradicals Behave Like Radicals?. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119 (21), 11291–11351. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S.; Catarina G.; Wu F.; Ortiz R.; Jacob D.; Eimre K.; Ma J.; Pignedoli C. A.; Feng X.; Ruffieux P.; Fernández-Rossier J.; Fasel R. Observation of Fractional Edge Excitations in Nanographene Spin Chains. Nature 2021, 598 (7880), 287–292. 10.1038/s41586-021-03842-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oteyza D. G.; Frederiksen T. Carbon-Based Nanostructures as a Versatile Platform for Tunable π-Magnetism. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2022, 34 (44), 443001. 10.1088/1361-648X/ac8a7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavliček N.; Mistry A.; Majzik Z.; Moll N.; Meyer G.; Fox D. J.; Gross L. Synthesis and Characterization of Triangulene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12 (4), 308–311. 10.1038/nnano.2016.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S.; Beyer D.; Eimre K.; Kezilebieke S.; Berger R.; Gröning O.; Pignedoli C. A.; Müllen K.; Liljeroth P.; Ruffieux P.; Feng X.; Fasel R. Topological Frustration Induces Unconventional Magnetism in a Nanographene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15 (1), 22–28. 10.1038/s41565-019-0577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryn’ova G.; Coote M. L.; Corminboeuf C. Theory and Practice of Uncommon Molecular Electronic Configurations. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2015, 5 (6), 440–459. 10.1002/wcms.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H.; Peng Q.; Chen X.-K.; Gu Q.; Dong S.; Evans E. W.; Gillett A. J.; Ai X.; Zhang M.; Credgington D.; Coropceanu V.; Friend R. H.; Brédas J.-L.; Li F. High Stability and Luminescence Efficiency in Donor–Acceptor Neutral Radicals Not Following the Aufbau Principle. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18 (9), 977–984. 10.1038/s41563-019-0433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara T.; Matsushita M. M. Spintronics in Organic π-Electronic Systems. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19 (12), 1738–1753. 10.1039/b818851n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasemthaveechok S.; Abella L.; Jean M.; Cordier M.; Vanthuyne N.; Guizouarn T.; Cador O.; Autschbach J.; Crassous J.; Favereau L. Carbazole Isomerism in Helical Radical Cations: Spin Delocalization and SOMO–HOMO Level Inversion in the Diradical State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144 (16), 7253–7263. 10.1021/jacs.2c00331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R.; Fu K.; Fang Y.; Zhou J.; Shi L. Site-Specific C(sp3)–H Aminations of Imidates and Amidines Enabled by Covalently Tethered Distonic Radical Anions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (46), 20682–20690. 10.1002/anie.202008806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levernier E.; Jaouadi K.; Zhang H.; Corcé V.; Bernard A.; Gontard G.; Troufflard C.; Grimaud L.; Derat E.; Ollivier C.; Fensterbank L. Phenyl Silicates with Substituted Catecholate Ligands: Synthesis, Structural Studies and Reactivity. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27 (34), 8782–8790. 10.1002/chem.202100453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awaga K.; Sugano T.; Kinoshita M. Ferromagnetic Intermolecular Interaction in the Galvinoxyl Radical: Cooperation of Spin Polarization and Charge-Transfer Interaction. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1987, 141 (6), 540–544. 10.1016/0009-2614(87)85077-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto T.; Yamaga S.; Nakai M.; Ohmori K.; Tsujii M.; Nakatsuji H.; Fujita H.; Yamauchi J. Intramolecular Spin-Spin Exchange in Cation Radicals of Tetrathiafulvalene Derivatives Substituted with Imino Pyrolidine- and Piperidine-1-Oxyls. Chem. Lett. 1993, 22 (8), 1361–1364. 10.1246/cl.1993.1361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazaki J.; Matsushita M. M.; Izuoka A.; Sugawara T. Novel Spin-Polarized TTF Donors Affording Ground State Triplet Cation Diradicals. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40 (27), 5027–5030. 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00925-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izuoka A.; Hiraishi M.; Abe T.; Sugawara T.; Sato K.; Takui T. Spin Alignment in Singly Oxidized Spin-Polarized Diradical Donor: Thianthrene Bis(Nitronyl Nitroxide). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122 (13), 3234–3235. 10.1021/ja9916759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai H.; Izuoka A.; Sugawara T. Design, Preparation, and Electronic Structure of High-Spin Cation Diradicals Derived from Amine-Based Spin-Polarized Donors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122 (40), 9723–9734. 10.1021/ja994547t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazaki J.; Chung I.; Matsushita M. M.; Sugawara T.; Watanabe R.; Izuoka A.; Kawada Y. Design and Preparation of Pyrrole-Based Spin-Polarized Donors. J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13 (5), 1011–1022. 10.1039/b211986b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H.; Mogi R.; Matsushita M. M.; Miyagi T.; Kawada Y.; Sugawara T. Synthesis and Properties of TSF-Based Spin-Polarized Donor. Polyhedron 2009, 28 (9), 1996–2000. 10.1016/j.poly.2008.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kusamoto T.; Kume S.; Nishihara H. Realization of SOMO–HOMO Level Conversion for a TEMPO-Dithiolate Ligand by Coordination to Platinum(II). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (42), 13844–13845. 10.1021/ja805751h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusamoto T.; Kume S.; Nishihara H. Cyclization of TEMPO Radicals Bound to Metalladithiolene Induced by SOMO–HOMO Energy-Level Conversion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49 (3), 529–531. 10.1002/anie.200905132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y.; Yoshioka M.; Saigo K.; Hashizume D.; Ogura T. Hydrogen-Bonding-Assisted Self-Doping in Tetrathiafulvalene (TTF) Conductor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (29), 9995–10002. 10.1021/ja809425b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westcott B. L.; Gruhn N. E.; Michelsen L. J.; Lichtenberger D. L. Experimental Observation of Non-Aufbau Behavior: Photoelectron Spectra of Vanadyloctaethylporphyrinate and Vanadylphthalocyanine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122 (33), 8083–8084. 10.1021/ja994018p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gryn’ova G.; Marshall D. L.; Blanksby S. J.; Coote M. L. Switching Radical Stability by pH-Induced Orbital Conversion. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5 (6), 474–481. 10.1038/nchem.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So S.; Kirk B. B.; Wille U.; Trevitt A. J.; Blanksby S. J.; da Silva G. Reactions of a Distonic Peroxyl Radical Anion Influenced by SOMO–HOMO Conversion: An Example of Anion-Directed Channel Switching. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22 (4), 2130–2141. 10.1039/C9CP05989J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Zhang H.; Pink M.; Olankitwanit A.; Rajca S.; Rajca A. Radical Cation and Neutral Radical of Aza-Thia[7]Helicene with SOMO–HOMO Energy Level Inversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (23), 7298–7304. 10.1021/jacs.6b01498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajca A.; Shu C.; Zhang H.; Zhang S.; Wang H.; Rajca S. Thiophene-Based Double Helices: Radical Cations with SOMO–HOMO Energy Level Inversion. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97 (6), 1376–1390. 10.1111/php.13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasemthaveechok S.; Abella L.; Jean M.; Cordier M.; Roisnel T.; Vanthuyne N.; Guizouarn T.; Cador O.; Autschbach J.; Crassous J.; Favereau L. Axially and Helically Chiral Cationic Radical Bicarbazoles: SOMO–HOMO Level Inversion and Chirality Impact on the Stability of Mono- and Diradical Cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (48), 20409–20418. 10.1021/jacs.0c08948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanushi A.; Kimura S.; Kusamoto T.; Tominaga M.; Kitagawa Y.; Nakano M.; Nishihara H. NIR Emission and Acid-Induced Intramolecular Electron Transfer Derived from a SOMO–HOMO Converted Non-Aufbau Electronic Structure. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123 (7), 4417–4423. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b08574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medina Rivero S.; Shang R.; Hamada H.; Yan Q.; Tsuji H.; Nakamura E.; Casado J. Non-Aufbau Spiro-Conjugated Quinoidal & Aromatic Charged Radicals. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 94 (3), 989–996. 10.1246/bcsj.20200385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sentyurin V. V.; Levitskiy O. A.; Bogdanov A. V.; Yankova T. S.; Dorofeev S. G.; Lyssenko K. A.; Gontcharenko V. E.; Magdesieva T. V. Stable Spiro-Fused Diarylaminyl Radicals: A New Type of a Neutral Mixed-Valence System. Chem. - Eur. J. 2023, 29 (43), e202301250 10.1002/chem.202301250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Sevilla M. D. Proton Transfer Induced SOMO-to-HOMO Level Switching in One-Electron Oxidized A-T and G-C Base Pairs: A Density Functional Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118 (20), 5453–5458. 10.1021/jp5028004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Sevilla M. D. SOMO–HOMO Level Inversion in Biologically Important Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122 (1), 98–105. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata R.; Wang Z.; Miyazawa Y.; Antol I.; Yamago S.; Abe M. SOMO–HOMO Conversion in Triplet Carbenes. Org. Lett. 2021, 23 (13), 4955–4959. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Murata R.; Abe M. SOMO–HOMO Conversion in Triplet Cyclopentane-1,3-Diyl Diradicals. ACS Omega 2021, 6 (35), 22773–22779. 10.1021/acsomega.1c03125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya T.; Katsuoka Y.; Yoza K.; Sato H.; Mazaki Y. Stereochemistry, Stereodynamics, and Redox and Complexation Behaviors of 2,2′-Diaryl-1,1′-Biazulenes. ChemPlusChem. 2019, 84 (11), 1659–1667. 10.1002/cplu.201900262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabuj M. A.; Muoh O.; Huda M. M.; Rai N. Non-Aufbau Orbital Ordering and Spin Density Modulation in High-Spin Donor–Acceptor Conjugated Polymers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24 (38), 23699–23711. 10.1039/D2CP02355E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abella L.; Crassous J.; Favereau L.; Autschbach J. Why Is the Energy of the Singly Occupied Orbital in Some Radicals below the Highest Occupied Orbital Energy?. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33 (10), 3678–3691. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.1c00683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shu C.; Zhang H.; Olankitwanit A.; Rajca S.; Rajca A. High-Spin Diradical Dication of Chiral π-Conjugated Double Helical Molecule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (43), 17287–17294. 10.1021/jacs.9b08711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht F.; Fatayer S.; Pozo I.; Tavernelli I.; Repp J.; Peña D.; Gross L. Selectivity in Single-Molecule Reactions by Tip-Induced Redox Chemistry. Science 2022, 377 (6603), 298–301. 10.1126/science.abo6471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q.; Mateo L. M.; Robles R.; Lorente N.; Ruffieux P.; Bottari G.; Torres T.; Fasel R. Bottom-up Fabrication and Atomic-Scale Characterization of Triply Linked, Laterally π-Extended Porphyrin Nanotapes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (29), 16208–16214. 10.1002/anie.202105350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschitschibabin A. E. Über Einige Phenylierte Derivate Des p, p-Ditolyls. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1907, 40 (2), 1810–1819. 10.1002/cber.19070400282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery L. K.; Huffman J. C.; Jurczak E. A.; Grendze M. P. The Molecular Structures of Thiele’s and Chichibabin’s Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108 (19), 6004–6011. 10.1021/ja00279a056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan B.; Li C.; Zhao Y.; Gröning O.; Zhou X.; Zhang P.; Guan D.; Li Y.; Zheng H.; Liu C.; Mai Y.; Liu P.; Ji W.; Jia J.; Wang S. Resolving Quinoid Structure in Poly(Para-Phenylene) Chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (22), 10034–10041. 10.1021/jacs.0c01930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Rossier J.; Palacios J. J. Magnetism in Graphene Nanoislands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99 (17), 177204 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.177204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz R.; Boto R. A.; García-Martínez N.; Sancho-García J. C.; Melle-Franco M.; Fernández-Rossier J. Exchange Rules for Diradical π-Conjugated Hydrocarbons. Nano Lett. 2019, 19 (9), 5991–5997. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S.; Vilas-Varela M.; Lieske L.-A.; Ortiz R.; Fatayer S.; Rončević I.; Albrecht F.; Frederiksen T.; Peña D.; Gross L. Bistability between π-Diradical Open-Shell and Closed-Shell States in Indeno[1,2-a]Fluorene. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16 (5), 755–761. 10.1038/s41557-023-01431-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi A.; Shimon L. J. W.; Gidron O. Helically Locked Tethered Twistacenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (26), 8086–8090. 10.1021/jacs.8b04447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann C.; Swart I.; Repp J. Controlling the Orbital Sequence in Individual Cu-Phthalocyanine Molecules. Nano Lett. 2013, 13 (2), 777–780. 10.1021/nl304483h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. Y.; Kim K. S. Tuning Molecular Orbitals in Molecular Electronics and Spintronics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43 (1), 111–120. 10.1021/ar900156u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giessibl F. J. High-Speed Force Sensor for Force Microscopy and Profilometry Utilizing a Quartz Tuning Fork. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 73 (26), 3956–3958. 10.1063/1.122948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht T. R.; Grütter P.; Horne D.; Rugar D. Frequency Modulation Detection Using High-Q Cantilevers for Enhanced Force Microscope Sensitivity. J. Appl. Phys. 1991, 69 (2), 668–673. 10.1063/1.347347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blum V.; Gehrke R.; Hanke F.; Havu P.; Havu V.; Ren X.; Reuter K.; Scheffler M. Ab Initio Molecular Simulations with Numeric Atom-Centered Orbitals. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2009, 180 (11), 2175–2196. 10.1016/j.cpc.2009.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scuseria G. E.; Staroverov V. N.. Progress in the Development of Exchange-Correlation Functionals. In Theory and Applications of Computational Chemistry; Elsevier, 2005; pp 669–724. 10.1016/B978-044451719-7/50067-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tkatchenko A.; Scheffler M. Accurate Molecular Van Der Waals Interactions from Ground-State Electron Density and Free-Atom Reference Data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102 (7), 073005 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.073005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S.; Vilas-Varela M.; Fatayer S.; Albrecht F.; Peña D.; Gross L.. Observation of SOMO-HOMO Inversion in a Polycyclic Conjugated Hydrocarbon. 2024, arXiv:2403.01484 [cond-mat.mes-hall]. arXiv.org e-Print archive. 10.48550/arXiv.2403.01484 (accessed May 17, 2024). [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.