Editor—The BMA discussion paper Clinical Indicators (League Tables) touches on the issue of how performance indicator systems can have dysfunctional behavioural and managerial implications.1 Winston shows how this applies to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority's league tables of in vitro fertilisation clinics.2 Our research looks at the dysfunctional effects of league tables in education and may be relevant to some of the issues surrounding league tables in the health sector.

We have recently reported a comparison between two systems, one with league tables (English primary schools) and one without (Scottish primary schools). In most other respects the two systems are similar. The research entailed a questionnaire survey of heads and teachers from 54 randomly selected primary schools in England and Scotland during 1999.

Some of the key findings were:

English schools were more likely to report concentrating on meeting their targets, at the expense of other important objectives

The target setting and testing process apparently had a narrowing effect on the curriculum in England

English schools were more like to say that they had concentrated resources on “borderline children”—those close to reaching the threshold—who would improve their league table position

English schools particularly thought that the target setting and testing process had increased the “blame culture”

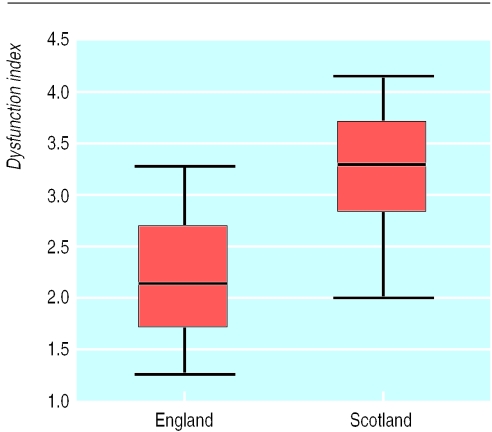

These findings were not entirely surprising and had been predicted (for example, by Smith3), but what was surprising was the substantial difference between the two countries. Seven questions were combined to form a dysfunction index. On a scale of 1 (maximum dysfunction) to 5 (no dysfunction), English primary schools scored 2.17 and Scottish 3.19 (P<0.001; effect size 1.68). The figure shows the results.

As well as the differences, we found several important (though not significant) similarities:

Both groups wanted access to performance data for their internal use—that is, they were not against performance indicators as such

Schools in both countries seemed to be under similar pressure to meet targets. This suggests that having league tables does not necessarily apply greater pressure than other less public techniques

Parents in England were no more likely to make reference to school test results than their Scottish counterparts. This questions one of the fundamental justifications of league tables: giving consumers information that they can use to put pressure on “their” schools

Although there were difficulties in allowing for other factors that may have an influence on the responses to the questionnaire, the data should give pause for thought. Careful consideration should be given to the unintended consequences of league tables.

Figure.

Boxplots showing mean (SD) degree of dysfunction for each country (the lower the number the greater the dysfunction)

Footnotes

This letter is based on a paper presented to the European educational research conference, Edinburgh, September 2000, available on line: www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00001555.doc

References

- 1.British Medical Association. Clinical indicators (league tables)—a discussion paper. London: BMA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winston R. League tables of in vitro fertilisation clinics misinform patients. BMJ. 1998;317:1593. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith P. Outcome-related performance indicators and organizational control in the public sector. Br J Management. 1993;4:135–152. [Google Scholar]