BACKGROUND

Travel for transplant involves the movement of people and financial assets across international borders for the express purpose of obtaining an organ transplant. In the United States, this refers to US citizens who travel abroad for transplants and the influx of non-US citizen nonresidents traveling for transplants. Given that those on the US waitlist far exceed the number of organs donated, and many patients die awaiting transplant, parity in the allotment is critical. In this context, travel to the United States for transplant becomes fraught with ethical considerations.

Lack of transplant services in many countries of the world, whether due to insufficient resources and medical infrastructure or cultural or religious beliefs that do not align with deceased donor transplant, drive noncitizen nonresidents to travel to the United States for transplant. Legally, noncitizen nonresidents are eligible for transplantation in the United States. Criteria for organ allocation rely on medical necessity and proximity of available organs and do not take into account political designations such as citizenship and residency1; therefore, citizens and noncitizens alike face the same criteria for allotment. Ultimately, the decision to list is made by individual transplant centers.

An international summit in 2008 brought together experts to establish definitions, principles of practice, and recommendations on transplant across national borders.2 The Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism (DOI) emphasized “self-sufficiency in organ donation and transplantation,” meaning a country’s ability to meet its own needs using “donation and transplant services provided within the country and organs donated by its residents.”3 The 2018 update explicitly stated that travel for transplant becomes unethical if the resources diverted to nonresidents undermine the country’s ability to provide for its own residents.3

In the United States, the United Network for Organ Sharing manages the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, which is charged with the fair and equitable allocation of donated organs. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network policies historically recommended limiting transplanting noncitizen nonresidents by way of the “5% rule”, which subjected transplant centers who transplanted more that 5% noncitizen nonresidents to audit and formal review. However, no program was ever brought up for formal review.4 This was replaced in 2012 with an alternative policy that made residency and citizenship data publicly available in an effort to achieve greater transparency regarding transplant practices. Data collection categories were revised based on citizenship and residency status: US citizen, non-US citizen residing in the United States, and non-US citizen not residing in the United States (noncitizen/nonresident [NC/NR]). Importantly, a field was added indicating whether NC/NR candidates had traveled to the United States for the sole purpose of transplantation (noncitizen/nonresident; traveled for transplant [NC/NRTx])5 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

OPTN citizenship designation

| OPTN citizenship designation | |

|---|---|

| US Citizen | US Citizen |

| NC/R | Noncitizen/resident |

| NC/NR | Noncitizen/nonresident |

| NC/NRTx | Noncitizen/nonresident; traveled for transplant |

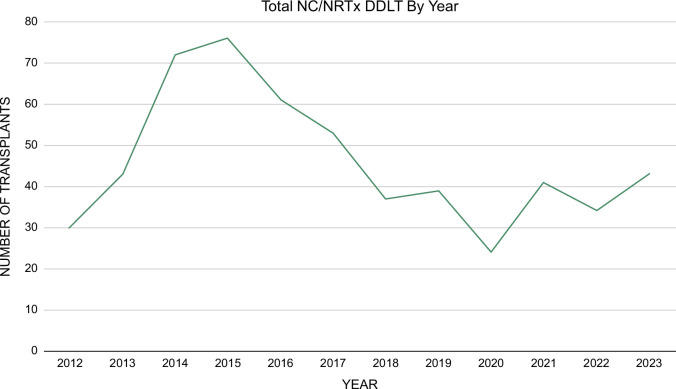

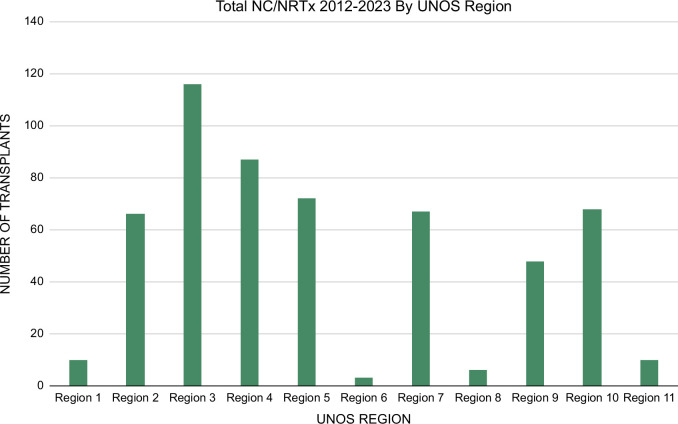

While the overall number of those who travel to the United States for transplant (henceforth referred to as NC/NRTx) is small relative to total transplants performed, representing 0.5% of all deceased donor transplants from 2013 to 20165 and 0.6% of all deceased donor liver transplants from 2012 to 20236 (Figure 1), there is significant regional variation in the practice5,7 (Figure 2). Given that allocation is dependent on region, some US residents who share the waitlist with NC/NRTx may be affected more than others. Furthermore, given persistent organ shortages, any allocation to noncitizen nonresidents may be in conflict with the DOI’s tenet of self-sufficiency.9

FIGURE 1.

Total NC/NRTx DDLT by year.6 Abbreviations: DDLT, deceased donor liver transplants; NC/NRTx, Noncitizen/nonresident traveled for transplant.

FIGURE 2.

Total NC/NRTx DDLT by region (2012–2023).8 Abbreviations: DDLT, deceased donor liver transplants; NC/NRTx, Noncitizen/nonresident traveled for transplant; UNOS, United Network for Organ Sharing.

ETHICAL FRAMEWORK

Core concepts in clinical medical ethics include autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, and utility (Table 2). The following analysis will focus on the concepts of justice and utility in the context of deceased donor liver transplants, as living donor liver transplant faces different issues of resource scarcity and is much less common.6

TABLE 2.

Core principles in medical ethics

| Core principles in medical ethics | |

|---|---|

| Autonomy | Individuals right to make own decisions |

| Beneficence | Acting out of a desire to help others in need, acting in their best interest |

| Non-maleficence | Avoiding harm to the individual |

| Justice | Treating all individuals fairly and equitably |

| Utility | Acting in the interest of the greatest good for all |

JUSTICE

Justice represents the principle of fairness to the individual and lies at the heart of ethical concerns regarding this practice. Is it fair to allow NC/NRTx when there are more US citizens and residents on the waitlist than organs available? This question will be addressed through the lens of 3 concepts: reciprocity, inequity in health care access, and inequity in wealth.

Reciprocity

Many have argued that it is not fair to allow NC/NRTx, citing the concept of reciprocity. NC/NRTx do not participate in the donor pool, nor do they participate in the tax system that supports transplant infrastructure. A commonly used counterargument to this focuses on the monetary contribution to the system made by these patients, many of whom are self-paying. All of this rests on the premise that organs belong to the nation-state10 as opposed to humankind overall, and this premise in itself is not without internal conflict: Does the organ belong to the state where the donor died? Where did they hold citizenship? Where do they reside? Reciprocity maintains its importance in the context of organs as a limited resource. An increase in the donor pool could be achieved by considering the reciprocity of organ donations across international borders, such as is done in Europe, though this may have limited practicality in the United States, given the geographic distances.

Inequity in access to care

Allowing NC/NRTx may exacerbate existing inequities, as those with more means already experience shorter waitlist times, lower rates of death on the waitlist, and higher transplant rates in part due to the ability to region shop.11 NC/NRTx may benefit from these disparities as they are often self-pay and are not bound by the regulations of insurance companies. Also, while they undergo the same process for listing as their US counterparts, they appear to have relatively lower waitlist-to-transplant times, lower waitlist mortality,12 and lower Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score5 at listing. This inequity is exacerbated by regional variation in the practice of transplanting noncitizen nonresidents where residents of certain regions are competing with NC/NRTx for organs more than others.

Inequity in wealth

Finally, travel to the United States for a transplant requires significant funding, whether personal wealth or sponsored by the country of origin, and therefore NC/NRTx often arrives from a small number of countries who happen to find themselves with available capital but without transplant infrastructure. In data collected from 2013 to 2016 after the intention to travel for transplant was recorded, 49% of total NC/NRTx liver and kidney listings and transplants were from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait alone.5 This presents a further inequity as many people in need of transplant worldwide do not have access to funds to pay the sticker price for the procedure. The higher reimbursement rate of those who are self-pay may also incentivize transplant centers to list NC/NRTx.

UTILITY

Utility represents acting for the greatest good for all. This usually pertains to allocation policies that aim to optimize benefits to all.

Defining the greatest good for all

If “all” represents humankind (citizens of the world) then any transplant offered provides the same amount of good. However, if “all” refers to US residents, then providing an organ to a noncitizen nonresident may not respect this principle, harkening back to the concept of reciprocity. Additionally, there is a lack of data regarding posttransplant outcomes of noncitizen nonresidents who return to their country of origin, and if their outcomes are not similar, one could argue that this was not the best use of the organ. There are no systematic approaches in place for long-term follow-up of these patients, but perhaps it is our responsibility to establish them. This might take the form of standardized requirements for communication between the United States and foreign providers, both before and following transplant, such as posttransplant video visits between the US hepatologist, the patient, and their local physician at set intervals. Ultimately, the most cost-effective and sustainable route to provide the greatest good for all may be to invest in establishing transplant infrastructure outside of the United States in keeping with DOI's emphasis on self-sufficiency.

Financial equality

As many NC/NRTx are self-pay, transplanting NC/NRTx does bring more money into the transplant system; however, there is no transparency regarding how these funds are spent. If, as some centers state, funds were used to provide transplants for patients otherwise unable to afford transplant care, this would support the utility of transplanting of NC/NRTx.

DOWNSTREAM EFFECTS

Taking all of this into account, there are several possible downstream effects of continuing to allow this practice. Of great concern has been the question of increased waitlist times for US residents if US organs are going to noncitizen nonresidents. Somewhat reassuringly, data collected by the 2017 Ad Hoc International Relations Committee for their report to United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network reviewed centers with the most transplants to NC/NR and concluded that there was no noticeable difference in time to transplant.12 More data will need to be collected to ensure that US residents’ access to transplant is not jeopardized and to account for regional variation in the practice.

As organ donation depends on public engagement with the system, it is also important to consider public perceptions of transplanting NC/NRTx. The only survey to evaluate public opinion showed that 30% of respondents felt that NC/NRTx should not be allowed, and furthermore, 38% stated they might be discouraged from donating organs if they knew that NC/NRTx could be listed for transplantation in their area.13 If the practice of NC/NRTx continues to grow, there is reason to be concerned that donor deterrence will grow as well, potentially widening an already significant discrepancy in supply and demand.

Finally, physicians and other health care workers may experience moral distress as they watch their own patients die on the waitlist knowing that an organ that could have saved them went to someone who traveled to obtain it, particularly given potentially financial motivations.

CONCLUSION—WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

There are many ethical issues inherent in the practice of transplanting NC/NRTx, and more data will need to be collected to ascertain the overall impact of these transplants on US residents. Moving forward, policymakers will need to decide whether the status quo is maintained and whether centers continue to make their own determinations of who is transplanted. If so, it will be the responsibility of each center to ensure the needs of their local community are met. No matter what policies are decided upon, it is incumbent upon us to take into account the concepts of justice and utility when considering their design. Given that there is not likely to be a straightforward or easy way to address these ethical considerations while organ shortages persist, the answer may lie in investing in other countries’ transplant infrastructure and supporting regional organ-sharing programs, which would lead to more efficient utilization of resources and a self-sufficient system more in line with the tenets of the DOI.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: DOI, Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism; NC/NR, noncitizen/nonresident; NC/NRTx, noncitizen/nonresident traveled for transplant.

Contributor Information

Hannah F. Roth, Email: hannah.roth@uchicagomedicine.org.

Andrew I. Aronsohn, Email: aaronsoh@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- 1. Committee, O. A. H. I. R. 2018 Summary of Non-U.S. Resident Transplant Activity.

- 2. Summit, S. C. of the I . Organ trafficking and transplant tourism and commercialism: The Declaration of Istanbul. Lancet. 2008;372:5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. The declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism (2018 Edition). Transplantation. 2019;103:218–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glazier AK, Danovitch GM, Delmonico FL. Organ transplantation for nonresidents of the United States: A policy for transparency. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:1740–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Delmonico FL, Gunderson S, Iyer KR, Danovitch GM, Pruett TL, Reyes JD, et al. Deceased donor organ transplantation performed in the United States for Noncitizens and Nonresidents. Transplantation. 2018;102:1124–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. OPTN DATA . https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/

- 7. Braun HJ, Amara D, Shui AM, Stock PG, Hirose R, Delmonico FL, et al. International travel for liver transplantation: A comprehensive assessment of the impact on the United States transplant system. Transplantation. 2022;106:e141–e152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. UNOS Regions . https://unos.org/community/regions/

- 9. Rahmel A, Feng S. Liver transplants for noncitizens/nonresidents: What is the problem, and what should be done? Am J Transplant. 2018;18:2620–2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen IG. Organs without borders? Allocating transplant organs, foreigners, and the importance of the nation-state. Law Contemp Prob. 2014;77:175–215. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hartsock JA, Ivy SS, Helft PR. Liver allocation to non‐US citizen non‐US residents: An ethical framework for a last‐in‐line approach. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1681–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferrante ND, Goldberg DS. Transplantation in foreign nationals: Lower rates of waitlist mortality and higher rates of lost to follow-up posttransplant. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:2663–2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Volk ML, Warren GJW, Anspach RR, Couper MP, Merion RM, Ubel PA, et al. Foreigners traveling to the US for transplantation may adversely affect organ donation: A national survey. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1468–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]