ABSTRACT

Background:

Tamarind seed aspiration is not frequent in children and is usually observed in kids from rural backgrounds, with easy access to tamarind fruits and their by-products.

Materials and Methods:

We report a retrospective review of five patients managed in the pediatric surgery department for tamarind seed aspiration into the tracheobronchial tree. The data were analyzed based on age, clinical presentation, bronchoscopic observations, and the challenges faced during the rigid bronchoscopic retrieval and postoperative course.

Results:

There were four boys and one girl with a median age of 10 years. High-resolution computed tomography thorax was done in all patients. The foreign body was identified in the right main bronchus in one and the left main bronchus in four patients. All five patients underwent rigid bronchoscopy and retrieval of the seed. Two patients had an early presentation (within a week) - they needed temporary tracheotomy as the swollen seed could not be negotiated through the narrow glottis. Two patients had a late presentation (around 15 days) - they required removal in piecemeal using crushing forceps and multiple insertions of bronchoscope prolonging surgical time. One patient presented at 22 days posttamarind aspiration. It was soft enough for easy disintegration with crocodile forceps and expeditiously removed in three to four pieces. All patients recovered uneventfully.

Conclusion:

Removal of tamarind seed foreign body from the tracheobronchial tree is challenging. Anticipating the difficulties and being prepared well, helps to reduce the intraoperative difficulty, and allow successful removal with favorable patient outcomes.

KEYWORDS: Aspiration, bronchoscopy, rigid, tamarind seed, tracheobronchial tract

INTRODUCTION

Accidental tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration is relatively common in children. The aspiration risk is higher in the 1–3 year age group due to their propensity for oral exploration, inadequately developed dentition and immature neuromuscular mechanisms of deglutition and airway protection.[1,2] Vegetative or organic foreign bodies such as ground nuts and peanuts account for about 75% of aspirated vegetable foreign bodies.[1,2,3] Tamarind seed aspiration is usually observed in kids from rural backgrounds, with easy access to tamarind fruits and their by-products.[2,4] Tamarind seeds obtained from the dried, ripe, and mature fruits of Tamarindus indica have a thick, hard, glossy brown/black coat making them slippery. The seeds are decorticated and roasted for consumption; decorticated seeds are obtained by removing the black/brown skin of the seeds and are white in color and undecorticated seeds are with brown/black seed coat. This slippery coat makes the seeds easily aspirable into the tracheobronchial tree. Herein, we report five children with tracheobronchial tamarind seed aspiration and also discuss the management difficulties during bronchoscopic retrieval.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective review of hospital records of five patients managed in the pediatric surgery department for tamarind seed aspiration. The data were analyzed based on their age and mode of clinical presentation, bronchoscopic observations, and the challenges faced during the rigid bronchoscopic retrieval and the postoperative course. The patients were telephoned to report for follow-up evaluation.

RESULTS

There were four boys and one girl. The median age was 10 years (range: 8–12 years). Two patients presented within 7 days of the incidence of aspiration, two presented after 15 days, and one presented on the 22nd day of aspiration of tamarind seed. Every patient had a history of choking following the tamarind seed aspiration. The other symptoms were cough, dyspnea, and lower respiratory tract infection. The patient’s demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics of the five patients with tamarind seed aspiration

| Age/sex | Duration (days) | Symptoms | Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 years/male | 6 | Tachypnea | Right main bronchus |

| 11 years/male | 4 | Dyspnea | Left main bronchus |

| 9 years/male | 16 | Dyspnea, LRTI | Left main bronchus |

| 10 years/female | 15 | Dyspnea, LRTI | Left main bronchus |

| 12 years/male | 22 | Persistent LRTI | Left main bronchus |

LRTI: Lower respiratory tract infection

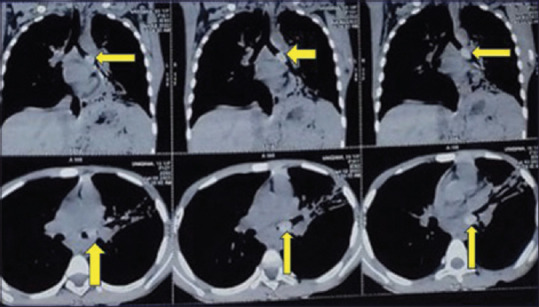

The high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) thorax was done to confirm the presence of tracheobronchial foreign body in all the patients [Figure 1]. Four patients had tamarind seed lodged in the left main bronchus and one in the right main bronchus. After HRCT confirmation, their parents were counseled for rigid bronchoscopy and foreign body removal. All patients underwent rigid bronchoscopy and foreign body removal under general anesthesia after initial stabilization and obtaining informed consent. The bronchoscopic findings and management are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

High-resolution computed tomography thorax showing foreign body in left main bronchus

Table 2.

Bronchoscopic findings and management of five patients with tamarind seed aspiration

| Presentation (days) | Duration (days) | Bronchoscopic findings | Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early (<7) | 6 | Swollen unimpacted seed in main bronchus with less mucous buildup and no pseudocavity | Optical forceps removal from bronchus easily and tracheotomy for retrieval from trachea |

| 4 | |||

| Delayed (7–20) | 16 | Swollen, impacted seed in the bronchus with mucous build-up and formation of pseudocavity | Multiple attempts at crushing and piecemeal retrieval |

| 15 | |||

| More delayed (>20) | 22 | Swollen, impacted seed in the bronchus with mucous build up and formation of pseudocavity; but softer and easily breakable | Easily crushed and retrieved in four pieces |

The intact tamarind seeds were identified in the main bronchus in the two patients presenting within 7 days of aspiration. There was minimal mucous build-up around the swollen seeds. The intact seeds were easily grasped with optical forceps and dislodged from the bronchi into the proximal airway. It was difficult to negotiate seeds through the glottis as the seed has swollen over a period and was not able to retrieve it. The retrieval was completed by creating a tracheotomy with subsequent insertion of a tracheostomy tube into the wound. The temporary tracheotomy was maintained for 72 h and closed once the airway edema settled.

In the two patients with a late presentation of around 15 days, the seed had imbibed fluid and had swollen with pseudocavity formation with surrounding bronchial wall edema causing near-total bronchial occlusion with distal lung collapse. These seeds were difficult to dislodge; hence, were crushed using crocodile forceps and removed in piecemeal. Operative time was also longer in these patients as multiple rigid bronchoscopy attempts were needed [Figure 2]. One of these patients required postoperative ventilatory support but both patients had an uneventful postoperative recovery.

Figure 2.

Bronchoscopic image of patient with delayed presentation showing retrieval of the crushed seed pieces and the pieces of excised seed

The patient presenting on the 22nd day postaspiration had only a chronic cough as the symptom. At rigid bronchoscopy, the aspirated seed was swollen with an inflammatory membrane around it [Figure 3]. It was soft enough for easy disintegration with crocodile forceps and expeditiously removed in three to four pieces. The patient was discharged on the 2nd postoperative day.

Figure 3.

Bronchoscopic image of patient with delayed presentation after 20 days showing the swollen seed with an inflammatory membrane around it in the left main bronchus

Postoperatively, intravenous antibiotics, nebulization, and analgesics were administered, along with intravenous dexamethasone to control airway edema. All the patients had no complaints on follow-up and had normal chest X-rays postoperatively.

DISCUSSION

The presentation of tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration can be varied, ranging from being asymptomatic to choking, cough, dyspnea, respiratory distress, and penetration symptoms.[5] Foreign bodies in the trachea and larynx can be life-threatening and can present as stridor. The typical history of aspiration may not be evident in all patients and may be unnoticed, especially in children; however, sudden choking or violent coughing episodes are the characteristic symptoms that should raise suspicion of accidental tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration. The violent coughing bouts are followed by an asymptomatic period, after which persistent bothersome cough remains the main symptom.[1] The combination of cough and dyspnea is a late symptom associated with retained tracheobronchial foreign bodies. A meticulous history obtained from the parents and clinical suspicion is essential to diagnose foreign body aspiration.[1] The clinical presentation differs in tamarind seed aspiration. It is more common in older children with a male predominance may due to their adventurous nature or outdoor activity. These cases are initially managed as upper and lower respiratory tract infections before further investigation or surgical referral if no suggestive history and due to their radiolucency.[1,2] Without an adult witness to foreign body inhalation, the referral time to a surgeon is usually more than 24 h and extends up to 30 days.[2]

T. indica is a monotypic genus and belongs to the subfamily Caesalpinioideae of the family Leguminosae (Fabaceae).[6] T. indica, commonly known as tamarind, is a multipurpose tropical fruit tree species in the Indian subcontinent. Tamarind is used as traditional medicine in India, Africa, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, and most tropical countries. Tamarind seeds are used in the textile and paper industry, as well as food additives, hence have commercial value and are stored in households, in many households, they are used as pawns in Indian board games.[6] It is commonly available in the villages and countryside roads and provides an ample opportunity for kids to pluck and eat during playtime. It poses a significant risk of accidental tracheobronchial aspiration in these kids.

The natural history of a vegetable foreign body aspiration is as follows: The initial coughing episode is due to reflex stimulation of the posterior pharynx and trachea, followed by a foreign body sensation and dry cough.[1] The seed in the respiratory tract enlarges by absorbing fluid and gets impacted, arresting further downstream movement in the airway.[1]

Chest X-ray posterior–anterior and lateral views are the initial imaging modalities in a patient with suspected foreign body aspiration.[1,2,3] The vegetative foreign bodies are radiolucent and covered in mucous build-up, making their identification difficult on chest X-rays.[1,2] The most common abnormalities are air trapping, compensatory emphysema, atelectasis, pneumonia, and mediastinal shift.[1,2,3,7,8] The sensitivity and specificity of chest X-rays in identifying tracheobronchial foreign bodies are 61% and 77%.[1,2] Low-dose computerized tomogram of the chest has a higher sensitivity in suspected aspirated foreign bodies. It can also detect potential complications such as lung collapse, consolidation, and pneumothorax. However, it is not preferred as the initial imaging because of higher radiation exposure to the children.[1,2,7,8] A strong clinical suspicion but unremarkable chest X-ray should mandate rigid bronchoscopy for definite diagnosis and treatment.[1]

The degree of respiratory distress determines the urgency of intervention. Patients with acute respiratory distress need prompt securing of the airway, even an emergency tracheotomy.[1] Removal of the organic foreign body should be performed in tertiary care hospital under general anesthesia with a facility for postoperative intensive care unit support, as kids with long-standing foreign bodies are prone for persistent respiratory symptoms in the postoperative period. The procedure time is longer because of swelling of the seed and concomitant airway edema necessitating piecemeal removal frequently. The patients may need postoperative ventilatory support for 48 h for the airway edema to settle. Continuous and effective communication between the anesthesiologist and surgeon is critical throughout the procedure and ensures the safe removal of the foreign body.

The five cases in this series describe the different retrieval techniques corresponding to the interval between aspiration of tamarind seed and bronchoscopic removal. All our cases were older children beyond the preschool age. Four out of five children had tamarind seed aspirated into the left mainstem bronchus, contrary to the reported literature, where the right bronchus is commonly affected.[1,2] Similar to our findings, Vane et al.[9] has also reported more incidence of foreign body lodgement in the left bronchus. The seeds remained stiff and swollen but unimpacted in the patients with early presentation (within 7 days). The seeds could be dislodged from the bronchus easily; however, a tracheotomy was required for complete retrieval to beyond the narrow glottis due to swollen seed. The ENT team kept as standby came to help in tracheotomy to retrieve the swollen tamarind seed in these two cases. A similar case has been reported by Arora et al.[10] requiring tracheotomy for removal of tamarind seed.

In patients with delayed presentation (7–14 days), the aspirated seeds became softer but were impacted by mucous build-up around the seed and pseudocavity formation. The procedure time was significantly longer to crush the seeds into pieces and retrieve them in piecemeal as these seeds were impacted and cannot be mobilized easily in the airway. With a further delay in presentation (20 days), the seed became quite soft and easy to crack. It facilitates faster piecemeal retrieval of the seed. Check bronchoscopy is needed to confirm the completeness procedure.

CONCLUSION

Tamarind seed is one of the uncommon vegetative foreign bodies inhaled into the tracheobronchial tree. Contact with the tracheobronchial tree leads to mucous build-up and swelling of the seeds, making their removal challenging. It often necessitates a temporary tracheotomy or piecemeal extraction for complete removal. The duration of the presentation also changes the management accordingly. In anticipation of extraction difficulties, appropriate instruments, including bronchoscopes of all sizes, a backup ENT surgeon, and a tracheostomy set, should be handy for successful removal.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Atul Jindal, Additional Professor and PICU In-charge, Department of Pediatrics, AIIMS, Raipur, Chhattisgarh.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sai Akhil R, Priya TG, Behera BK, Biswal B, Swain SK, Rath D, et al. Clinico-radiological profile and outcome of airway foreign body aspiration in children: A single-center experience from a tertiary care center in Eastern India. Cureus. 2022;14:e22163. doi: 10.7759/cureus.22163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passàli D, Lauriello M, Bellussi L, Passali GC, Passali FM, Gregori D. Foreign body inhalation in children: An update. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2010;30:27–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baram A, Sherzad H, Saeed S, Kakamad FH, Hamawandi AM. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies in children: The role of emergency rigid bronchoscopy. Glob Pediatr Health. 2017;4:2333794X17743663. doi: 10.1177/2333794X17743663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal S, Lyngdoh NM, Goyal A, Shunyu NB, Dey S, Yunus M. Impacted foreign body bronchus: Role of percussion in removal. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57:630–1. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.123349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baharloo F, Veyckemans F, Francis C, Biettlot MP, Rodenstein DO. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies: Presentation and management in children and adults. Chest. 1999;115:1357–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhadoriya SS, Ganeshpurkar A, Narwaria J, Rai G, Jain AP. Tamarindus indica: Extent of explored potential. Pharmacogn Rev. 2011;5:73–81. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.79102. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.79102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sivakumar E, Ramasubramaniam P. Foreign body aspiration in children. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2020;7:94–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naragund AI, Mudhol RS, Harugop AS, Patil PH, Hajare PS, Metgudmath VV. Tracheo-bronchial foreign body aspiration in children: A one year descriptive study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;66:180–5. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0416-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vane DW, Pritchard J, Colville CW, West KW, Eigen H, Grosfeld JL. Bronchoscopy for aspirated foreign bodies in children. Experience in 131 cases. Arch Surg. 1988;123:885–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400310099017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arora KK, Gandhi M, Gupta N, Choudhary A, Kaithwal A rara case of foreign body bronchus-A case report. Int J Med Anesthesiology. 2020;3:01–02. [Google Scholar]