Abstract

This report describes a detailed study of Ni phosphine catalysts for the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of dichloropyridines with halogen-containing (hetero)aryl boronic acids. With most phosphine ligands these transformations afford mixtures of mono- and diarylated cross-coupling products as well as competing oligomerization of the boronic acid. However, a ligand screen revealed that PPh2Me and PPh3 afford high yield and selectivity for monoarylation over diarylation as well as minimal competing oligomerization of the boronic acid. Several key observations were made regarding the selectivity of these reactions, including: (1) phosphine ligands that afford high selectivity for monoarylation fall within a narrow range of Tolman cone angles (between 136° and 157°); (2) more electron-rich trialkylphosphines afford predominantly diarylated products, while less-electron rich di- and triarylphosphines favor monoarylation; (3) diarylation proceeds via intramolecular oxidative addition; and (4) the solvent (MeCN) plays a crucial role in achieving high monoarylation selectivity. Experimental and DFT studies suggest that all these data can be explained based on the reactivity of a key intermediate: a Ni0-π complex of the monoarylated product. With larger, more electron-rich trialkylphosphine ligands, this π complex undergoes intramolecular oxidative addition faster than ligand substitution by the MeCN solvent, leading to selective diarylation. In contrast, with relatively small di- and triarylphosphine ligands, associative ligand substitution by MeCN is competitive with oxidative addition, resulting in selective formation of monoarylated products. The generality of this method is demonstrated with a variety of dichloropyridines and chloro-substituted aryl boronic acids. Furthermore, the optimal ligand (PPh2Me) and solvent (MeCN) are leveraged to achieve the Ni-catalyzed monoarylation of a broader set of dichloroarene substrates.

Keywords: cross-coupling, nickel catalysis, dichloropyridines, site-selectivity, monoarylation

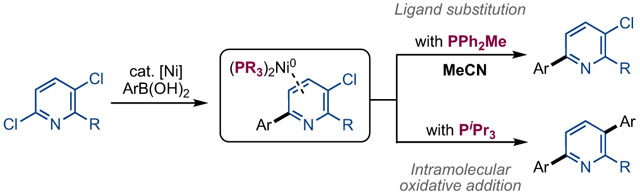

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

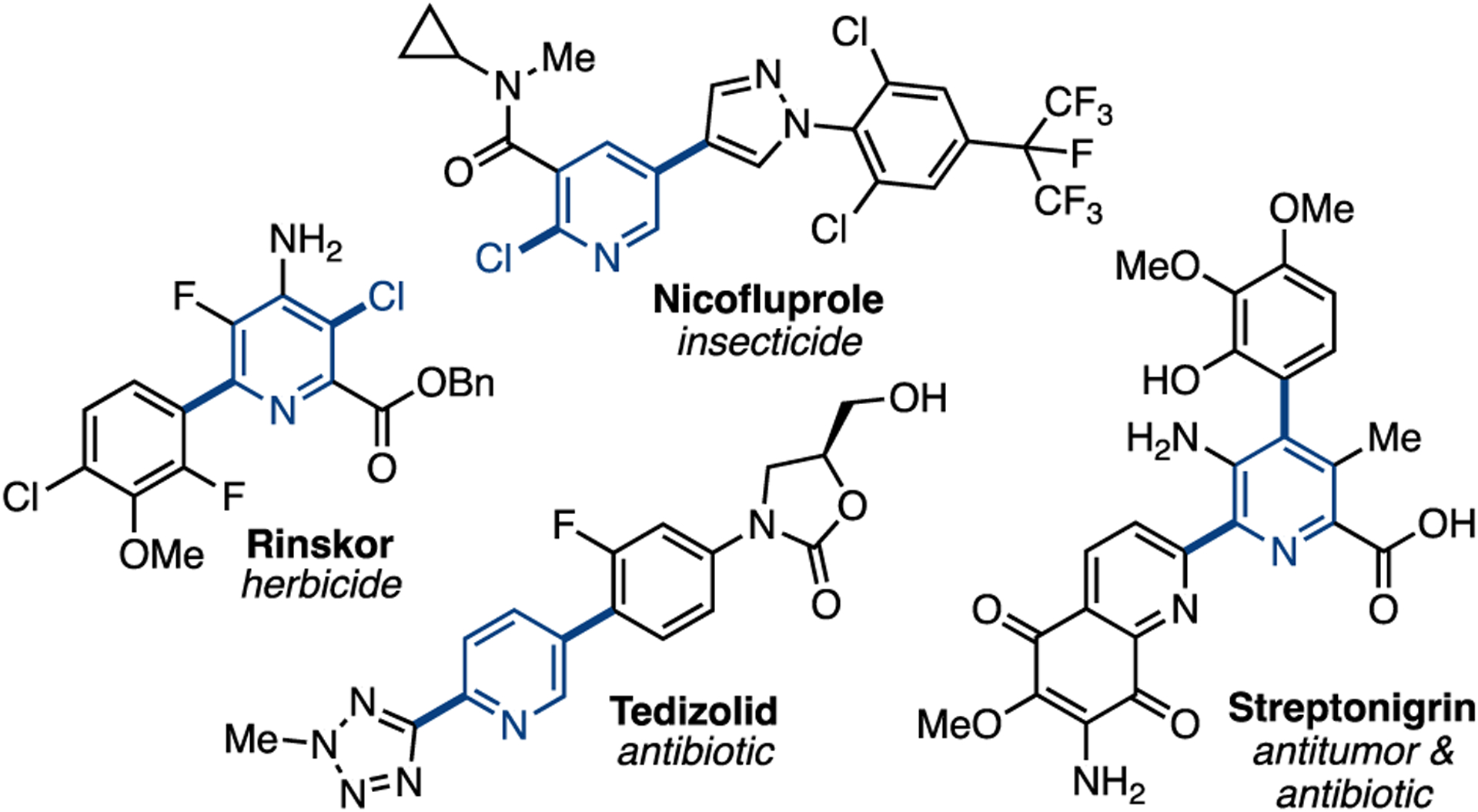

Dihalo(hetero)arenes, particularly dihalopyridines, have attracted considerable attention as electrophiles in transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.1 The selective monoarylation of these substrates affords monohalobiaryls, a common motif in bioactive molecules (Figure 1).2,3 Furthermore, the presence of a second electrophilic site on the product can be leveraged to access multiple functionalized (hetero)arenes, which also appear in drugs and agrochemicals (Figure 1).4

Figure 1.

Bioactive molecules accessible from cross-coupling reactions of 2,x-dihalopyridines (x = 3, 4, or 5)

Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of 2,x-dihalopyridines (x = 3, 4, or 5) with aryl nucleophiles have been well-studied, and most Pd catalysts exhibit high selectivity for monoarylated product A (Scheme 1a).5,6 In contrast, analogous reactions with nickel catalysts typically afford mixtures of A and the diarylated product B (Scheme 1a).7 The Ni-catalyzed reactions are further complicated when the aryl nucleophile contains a halide substituent, as this often leads to competing oligomerization/polymerization processes.8 Our overall objective was to identify a Ni catalyst system that promotes the selective C2-arylation of dichloropyridines with halide-substituted arylboronic acids.

Scheme 1.

Arylation of dichloropyridines: (a) Precedented reactivity with Pd and Ni; (b) Selective monoarylation with Ni

Herein, we report that selectivity in these transformations is highly sensitive to two factors: (1) the structure of the phosphine ligand and (2) the reaction solvent. The combination of diphenylmethylphosphine (PPh2Me) as ligand and acetonitrile (MeCN) as solvent proved optimal for achieving selective monoarylation of a variety of dichloropyridines and chloro-substituted aryl boronic acids (Scheme 1b). A combination of experimental and computational mechanistic studies provide insight into the origin of selectivity in this system. Finally, we demonstrate the generality of these findings (specifically the optimal ligand and solvent choice) for achieving selective monoarylation to other dichloroarene substrates.

Results and Discussion

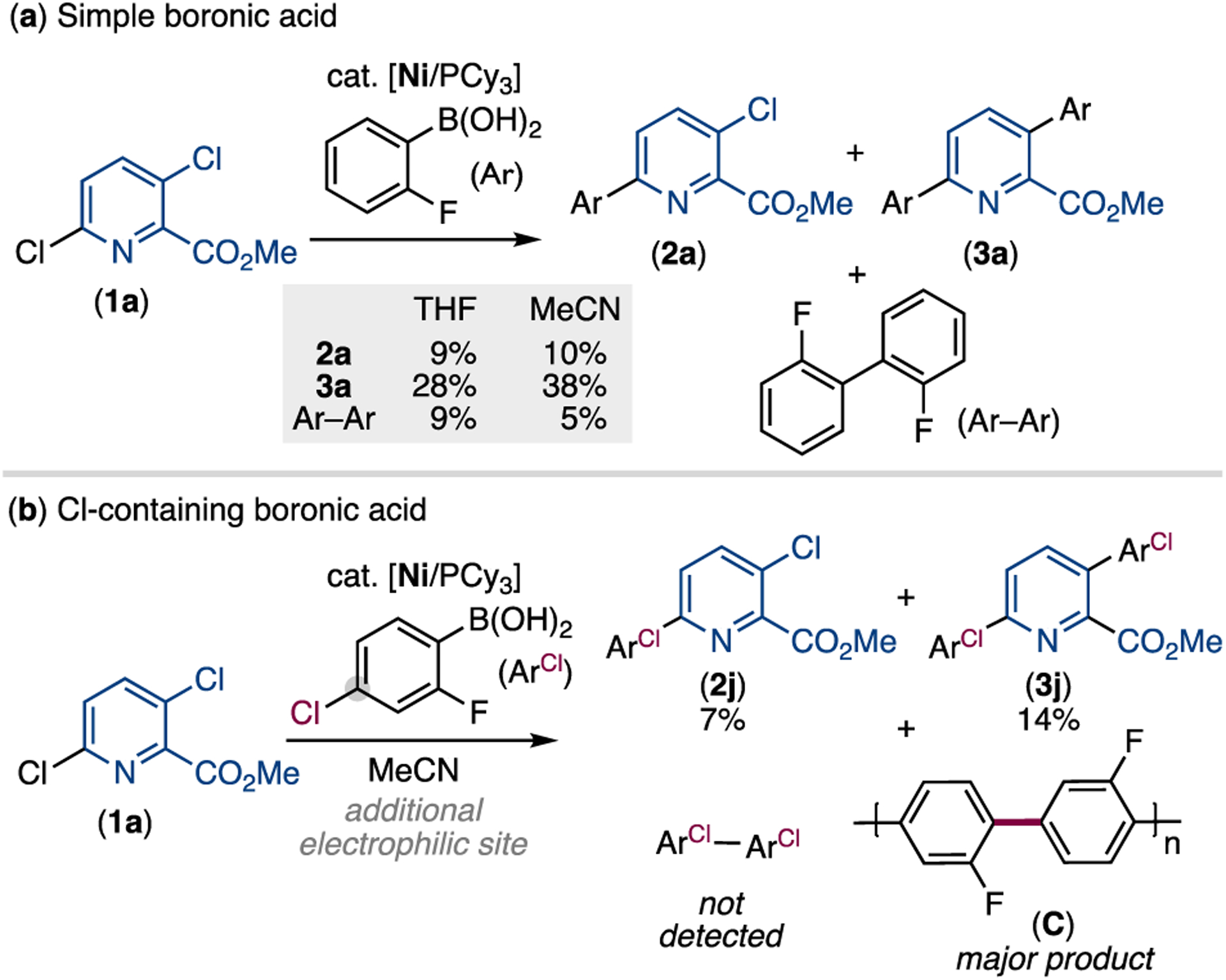

Our initial studies examined the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of methyl-2,5-dichloropicolinate (1a) with (2-fluorophenyl)boronic acid to benchmark reactivity and selectivity. Ni(cod)2 and PCy3 were selected as the pre-catalyst and ligand, respectively, as this combination has been widely used for Ni-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura couplings, including those involving chloropyridine substrates.9 The reaction was examined in THF and MeCN, two solvents that are commonly used in related cross-coupling reactions.6a,6f,6g,9b–e,10 As shown in Scheme 2a, the reactions afford mixtures of monoarylated 2a, diarylated 3a, and homocoupled boronic acid (Ar-Ar). In both solvents,9c diarylated 3a was the major product and was formed in comparable yield (28% versus 38%) and selectivity (3a : 2a = 3.1 : 1 versus 3.8 : 1). Overall, slightly higher reactivity was observed in MeCN (TON = 17 versus 13 in THF). As such, this was used as the solvent moving forward.

Scheme 2.

Product selectivity in Ni-catalyzed arylation of 1a with (a) simple aryl boronic acid and (b) chloro-containing aryl boronic acida,b

aConditions: 1a (1.0 equiv, 0.1 mmol), ArB(OH)>2 (1.1 equiv), Ni(cod)2 (5 mol%), PCy3 (20 mol%), K2CO3 (3.0 equiv), solvent (c = 0.2 M), 60 °C, 20 h. bYields determined by 19F NMR spectroscopy with trifluorotoluene as internal standard.

We next evaluated the Ni/PCy3 catalyst in an analogous reaction with (4-chloro-2-fluoropheny)boronic acid, which contains a potentially reactive aryl chloride substituent. This resulted in a 2 : 1 mixture of diarylated 3j and the corresponding monoarylation product 2j in low yields (14% and 7%, respectively), with no homocoupling observed. Further analysis revealed that the boronic acid was completely consumed, and an insoluble solid was generated. These observations implicate the oligomerization of (4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl)boronic acid to form C.8

Having established the baseline reactivity of the Ni(cod)2/PCy3 catalyst, we sought to identify phosphine ligands that afford high selectivity and yield for the monoarylation product, while limiting the polymerization of chloro-containing aryl boronic acids. We hypothesized that the challenges of polymerization were related to that of the mono- versus diarylation selectivity (vide infra), and thus first focused on addressing the latter issue. A series of phosphine ligands with varied electronic (mono-, di- and trialkyl substituents) and steric (wide range of Tolman cone angles) properties were evaluated. These ligands were first tested in the Ni-catalyzed coupling of 1a with 2.2 equiv of (2-fluorophenyl)boronic acid to afford 2a and/or 3a. Table 1 shows the phosphines that afforded >4 : 1 selectivity for either 2a or 3a. Data for all of the ligands examined are available in Table S1.

Table 1.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | ligand | 2a (%) | 3a (%) | 2a : 3a |

| 1 | PnBu3 | 2 | 23 | 1 : 12 |

| 2 | PEt3 | 4 | 35 | 1 : 8.7 |

| 3 | PtBu2Me | 4 | 64 | 1 : 16 |

| 4 | PiPr3 | 17 | 72 | 1 : 4.2 |

| 5 | PPh3 | 62 | 8 | 7.7 : 1 0 |

| 6 | PPh2Me | 83 | 14 | 5.9 : 1 . |

| 7 | PPh2Et | 55 | 5 | 11 : 1 . |

| 8 | PPh2iPr | 39 | 3 | 13 : 1 . |

| 9 | PPh2Cy | 33 | 2 | 17 : 1 . |

Reactions performed on 0.1 mmol scale (c = 0.2 M).

Yields determined by 19F NMR spectroscopy with trifluorotoluene as internal standard.

This phosphine screen uncovered several ligands (most notably PPh2Me, entry 6) that afford high yield and >5 : 1 selectivity for monoarylation, even when using 2.2 equiv of the boronic acid. Further optimization revealed that the use of 10 mol % of PPh2Me in combination with the commercially available, air-stable NiII precatalyst (PPh2Me)2Ni(o-tolyl)Cl11 resulted in 12 : 1 selectivity and 92% yield of 2a (Scheme 3). Finally, when the loading of boronic acid was reduced to 1.1 equiv, 2a and 3a were formed in 88% and 5%, respectively.12

Scheme 3.

Air-stable NiII precatalyst for the arylation of 1a

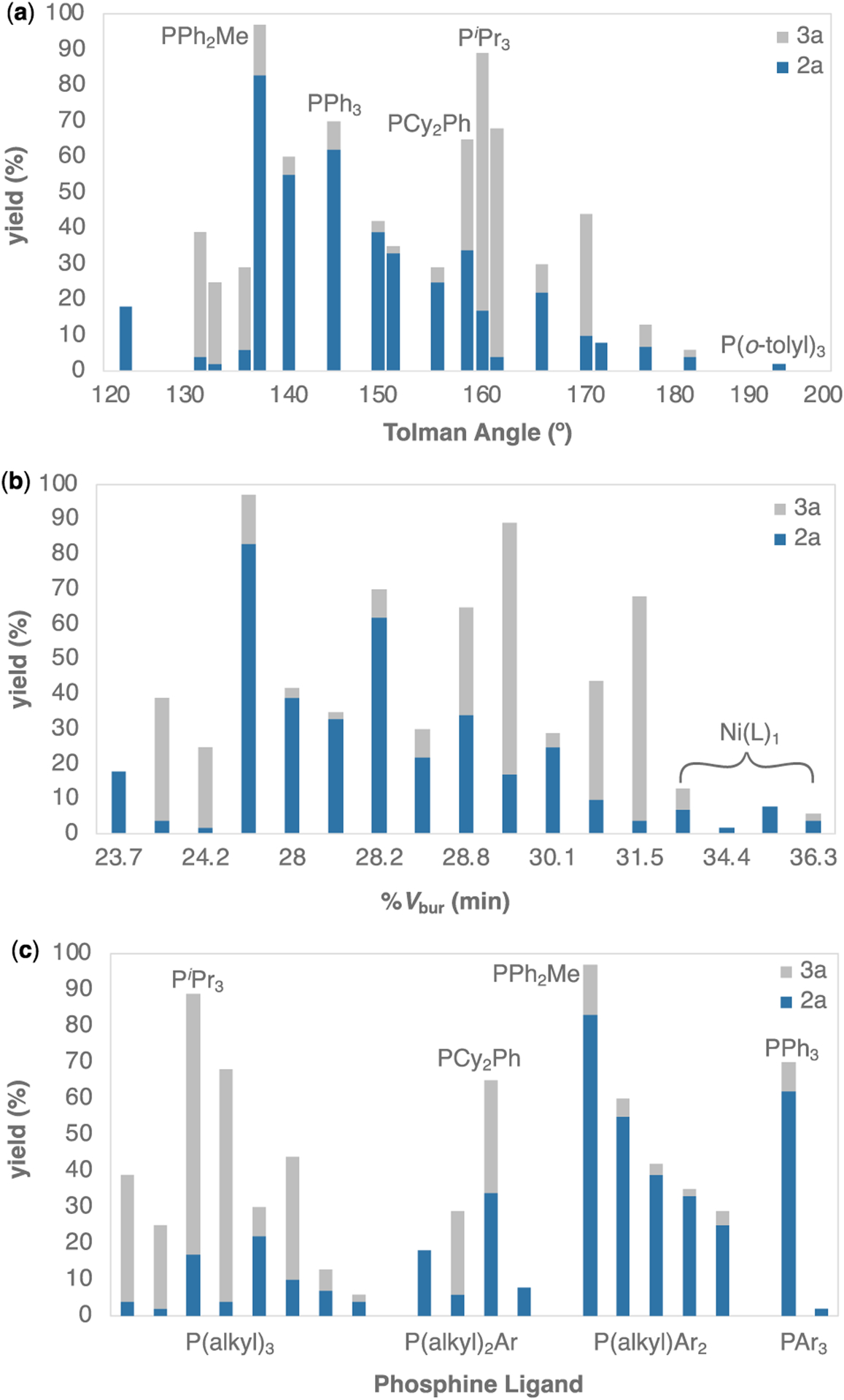

The observed ligand effects appear to originate from a combination of steric and electronic factors. To better understand these, we compared the experimental selectivities and yields to various descriptors of phosphine ligands.13 Steric effects in this transformation are most clearly visualized by plotting the combined yields of 2a (blue) and 3a (grey) as a function of the Tolman cone angle (Figure 2a).14,15 This plot shows that phosphines that afford high selectivity for monoarylation are generally clustered within a relatively narrow range of cone angles (~136° to 157°). At slightly higher or lower cone angles (±10° or more), the diarylated product predominates. Moreover, the overall yield of 2a + 3a decreases sharply with very large phosphines such as PtBu3 and P(o-tolyl)3 (cone angle ≥ 170°). The latter effect is even better visualized by plotting the overall yield versus the minimum percent buried volume (min %Vbur) of the phosphine, which shows a clear break at %Vbur ~ 32% (Figure 2b). This value represents the cut-off between mono- and bis-ligation in Ni0-phosphine oxidative addition transition states,13a suggesting that the mono-ligated Ni0 species are inactive for this cross-coupling.

Figure 2.

Analysis of arylation of 1a using steric parameters (a) Tolman cone angle (θ ) and (b) minimum percent buried volume (%Vbur). (c) Product distribution as a function of phosphine substitution pattern (Ar = aryl). Reaction conditions from Table 1. Showing monoarylated product (blue), and diarylated product (gray).

To visualize electronic effects, we plotted the combined yields of 2a and 3a versus various electronic parameters (Tolman electronic parameter, TEP; semiempirical electronic parameter, SEP; pKb; phosphine substitution; Figure S4). In most of these cases, the parameters are only available for a subset of the ligands, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Clustering the phosphines based on their substitution pattern [trialkyl, (dialkyl)aryl, (diaryl)alkyl, and triaryl] revealed the clearest trend (Figure 2c). The more electron rich and stronger sigma-donor trialkylphosphines generally afford good to excellent selectivity for the diarylated product 3a. In contrast, less electron rich and better π-accepting di- and triarylphosphines afford monoarylated 2a as the major product. The highest overall yield of and selectivity for 2a is observed with PPh2Me and PPh3, ligands that have cone angles in the optimal range (136° and 145°, respectively) along with di- or triaryl substitution.

To further rationalize the observed ligand effects on selectivity we considered the pathways to products 2a and 3a in more detail (Scheme 4). The formation of 2a is expected to proceed via a standard Suzuki coupling mechanism, involving initial oxidative addition at the more activated C(2)–Cl bond of 1a, transmetalation of the boronic acid to form intermediate I, C–C bond-forming reductive elimination to generate π-complex 2a-Ni0,16 and dissociation of 2a to release the product. In contrast, 3a could be formed via two distinct pathways starting from 𝜋-complex 2a-Ni0. In the first (Scheme 4a, Path A), the organic intermediate 2a could dissociate from Ni0 and subsequently re-engage with the catalyst to undergo C(5)–Cl oxidative addition. Alternatively, oxidative addition into the C(5)–Cl bond could occur in an intramolecular fashion at π-complex 2a-Ni0, without the release of free 2a (Scheme 4a, Path B).9c

Scheme 4.

Determining diarylation mechanism: (a) Proposed pathways; (b) Competition experiment; (c) Proposed mechanism

aReactions performed on 0.1 mmol scale (c = 0.2 M). bYields determined by 19F NMR using trifluorotoluene as internal standard.

To distinguish these possibilities, we conducted a competition study using equimolar quantities of dichloropyridine 1a, aryl(chloro)pyridine 2a’, and (2-fluorophenyl)boronic acid (Scheme 4b). This experiment was performed using PtBu2Me, which afforded the highest selectivity for the diarylated product in Table 1. All of the possible intermediates/products (2a, 2a’, 3a and 3a’) have distinct 19F NMR signals, enabling quantitative analysis of the product mixture by 19F NMR spectroscopy. As summarized in Scheme 4b, the major product after 20 h was 3a, derived from selective diarylation of 1a. Only traces of the monoarylated product 2a were detected. Furthermore, <5% of 2a’ underwent C(5)-arylation to produce 3a’. When the reaction was analyzed at shorter time points (1 h or 3 h, respectively), the yield of 3a was lower, but only traces of 2a were observed (see Supporting Information for complete details). Collectively, these data suggest that free 2a is not an intermediate en route to 3a. Instead, diarylation of 1a appears to involve two sequential Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions without dissociation of the Ni0–π intermediate, 2a-Ni0

This proposed pathway is analogous to the mechanism of living catalyst-transfer polymerization (CTP) reactions, where the intramolecular oxidative addition of a Ni0–π intermediate enables a chain-growth pathway.8 Indeed, the oligomerization of (4-chloro-2-fluoropheny)boronic acid observed in Scheme 2b with PCy3 as the ligand likely occurs via this pathway. In CTP polymerization, the steric and electronic properties of ligands have been shown to play a pivotal role in productive reactivity by controlling the rate of ligand displacement at the π–complex.8b,c We hypothesize that the ligand effects in our system are similarly related to the relative reactivity of 2a-Ni0 towards ligand substitution (for example, with the coordinating solvent acetonitrile) versus intramolecular oxidative addition (Scheme 5). In terms of steric effects, relatively small cone angle ligands are expected to facilitate associative substitution of solvent at 2a-Ni0 to release mono-arylated product 2a. Increasing the cone angle of the phosphine (and hence steric crowding at the Ni0 center) is expected to slow associative substitution relative to intramolecular oxidative addition, thus favoring diarylation product 3a. The phosphine substitution effects can also be rationalized based on the reactivity of 2a-Ni0. All other things being equal, more electron rich, sigma-donating trialkylphosphines are expected to increase the relative rate of oxidative addition17 compared to their di- or triaryl counterparts, thus pushing selectivity towards diarylation.

Scheme 5.

Proposed ligand exchange/solvent coordination as selectivity step for monoarylation of 1a

To experimentally probe the proposed role of acetonitrile in displacing the monoarylated product from 2a-Ni0, we evaluated the impact of solvent on product distribution with PPh2Me and PPh3 (Table 2).18 Under our standard conditions, both ligands afford high selectivity for the monoarylated product 2a, with ratios of 18 : 1 for PPh2Me and >20 : 1 for PPh3 (Table 2, entries 1 and 4). Changing the solvent from MeCN19 to THF led to a decrease in selectivity with PPh2Me, shifting the ratio to 10 : 1 (Table 2, entry 2), but still favoring monoarylation. More dramatically, a reversal of selectivity was observed with PPh3 in THF, leading to diarylated product 3a in 43% yield and 1 : 8.6 selectivity (Table 2, entry 5).

Table 2.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | PR3 | solvent | additive (equiv) | 2a (%) | 3a (%) | 2a : 3a |

| 1 | PPh2Me | MeCN | --- | 88 | 5 | 18 : 1 |

| 2 | THF | --- | 90 | 9 | 10 : 1 | |

| 3 | THF | MeCN (0.5) | 85 | 5 | 17 : 1 | |

| 4 | PPh3 | MeCN | --- | 53 | 1 | 53 : 1 |

| 5 | THF | --- | 5 | 43 | 1 : 8.6 | |

| 6 | THF | MeCN (0.5) | 51 | 21 | 2.4 : 1 | |

| 7 | THF | MeCN (1) | 76 | 24 | 3.2 : 1 | |

| 8 | THF | MeCN (2) | 80 | 11 | 7.2 : 1 | |

| 9 | THF | sulfolane (1) | 4 | 46 | 1 : 11 | |

Reactions performed on 0.1 mmol scale (c = 0.2 M).

Yields determined by 19F NMR using trifluorotoluene as internal standard. [Ni] = (PR3)2Ni(o-tolyl)Cl.

We next titrated various equivalents of MeCN into the THF reaction mixtures, with the hypothesis that this would serve to displace the monoarylated product from 2a-Ni0 and thus shift selectivity back towards 2a. Indeed, the addition of just 0.5 equiv of MeCN restored high (17 : 1) selectivity with PPh2Me (Table 2, entry 3). With PPh3, the selectivity responded in a dose-dependent manner, with increasing formation of 2a as more MeCN was added (Table 2, entries 6–8). Finally, to rule out effects related to solvent polarity changes, we examined the impact of highly polar yet weakly coordinating sulfolane as an additive.20 The reaction with PPh3 afforded 3a as the major product, with comparable yield and selectivity as in THF alone. This result indicates that the role of MeCN is not simply to increase the polarity of the reaction mixture. Instead, it implicates MeCN serving as a coordinating ligand to displace the monoarylated product from 2a-Ni0.

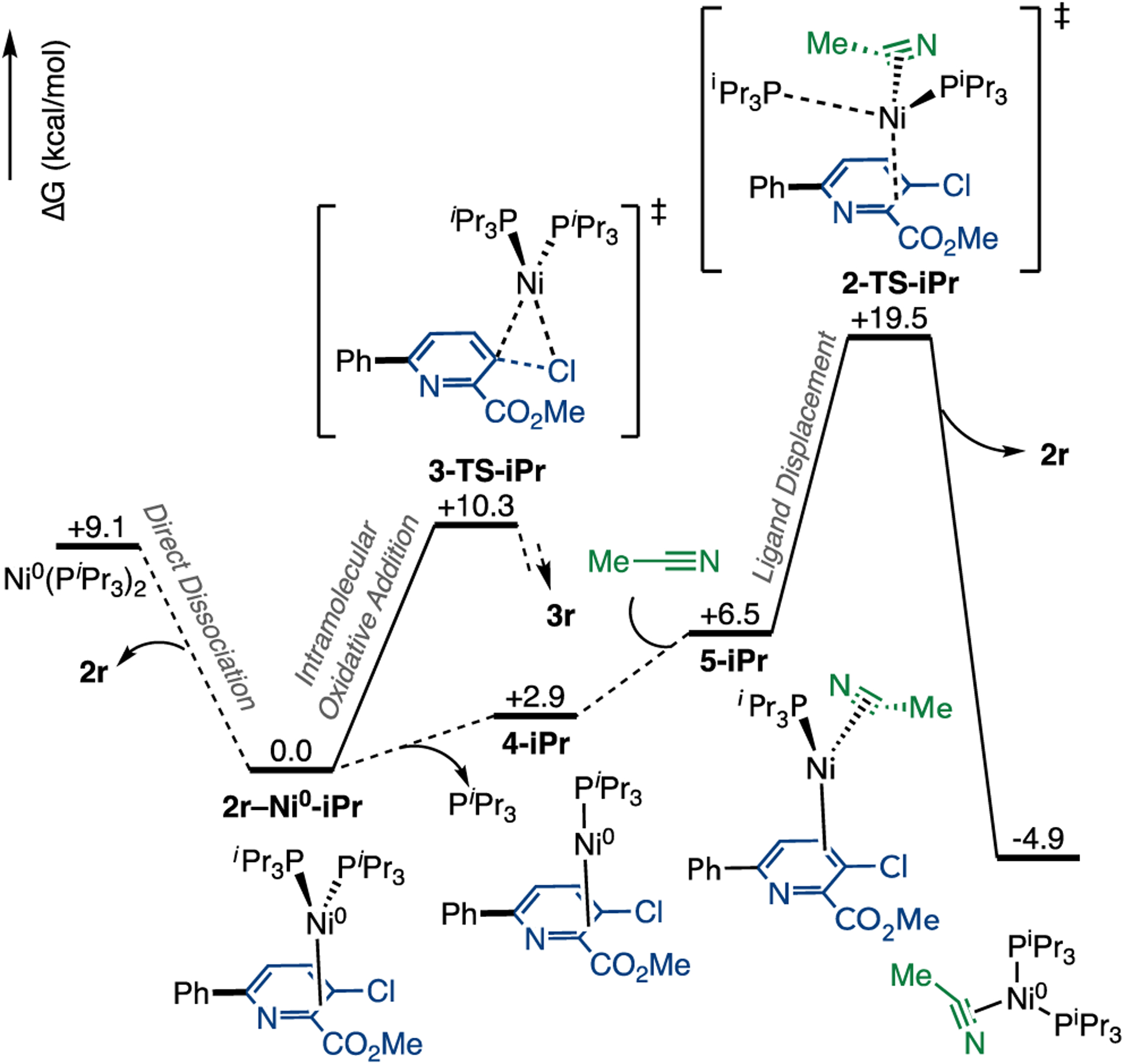

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted to probe the reactivity of the Ni0 π-complex,21 using PPh3 as a representative ligand that favors monoarylation (Figure 3) and PiPr3 as a representative ligand that favors diarylation (Figure 4). These symmetrical phosphines were selected to simplify the calculations by minimizing the number of accessible ligand conformers. The pi-bound substrate for the calculations was 2r, which contains a phenyl group at the 2-position. Thermodynamic quantities were calculated at 60 °C, applying corrections for concentrations consistent with the conditions in Table 1 (see SI for details).22,23 In the PPh3 system, intramolecular oxidative addition (3-TS-PPh3) and associative displacement of Ni0 by MeCN (2-TS-PPh3) are energetically comparable (ΔG‡ = 17.5 and 16.7 kcal/mol) at the level of theory used. The difference in these activation barriers is 0.8 kcal/mol favoring diarylation, whereas the experimental selectivity with PPh3 corresponds to ΔΔG‡ ~1.4 kcal/mol favoring monoarylation. Overall, the computed ΔΔG‡ differs from experiment by 2.2 kcal/mol, an error value within range of what is typical for DFT. Most importantly, the calculations implicate a ligand displacement pathway that is energetically competitive with oxidative addition. An alternative pathway for release of 2r involving direct dissociation to generate 2r and 14e– Ni(PPh3)2 is much less likely due to the high free energy of the coordinatively unsaturated nickel(0) fragment (26.1 kcal/mol). Thus, overall the calculations are consistent with the involvement of MeCN in displacing Ni0 from the monoarylated product, rather than direct dissociation of 2r from Ni(PPh3)2.

Figure 3.

Computed reaction free energy diagram for pathways leading to mono- and diarylation of 1a using PPh3.

Figure 4.

Computed reaction free energy diagram for pathways leading to mono- and diarylation of 1a using PiPr3.

The DFT calculations with PiPr3 as the ligand show very different results (Figure 4). Here, the barrier for oxidative addition at 2r-Ni0-PiPr3 is significantly lower than that with PPh3 (ΔG‡ = 10.3 versus 16.7 kcal/mol, respectively), while the lowest energy pathway for ligand displacement has a significantly higher ΔG‡ of 19.5 kcal/mol (compared to 17.5 kcal/mol for PPh3). Furthermore, the calculations indicate that this ligand displacement takes place by a different mechanism than for the PPh3 analogue, involving (i) initial dissociation of one PiPr3 ligand, (ii) coordination of MeCN to form (PiPr3)(MeCN)Ni0-2r, and (iii) reaction of this new π-complex with PiPr3 to release 2r. In contrast, a transition structure involving associative substitution at the (PiPr3)2Ni0–π intermediate (analogous to 2-TS in Figure 3) could not be located. Unlike Ni(PPh3)2, direct dissociation of Ni(PiPr3)2 may be feasible based on the calculated thermodynamics of this step, but we were unable to find a transition state for this pathway. Overall, these results suggest that a combination of faster oxidative addition and slower release of 2r from Ni0 result in a preference for diarylation product 3r with PiPr3.

We next evaluated the scope of this transformation with respect to the dichloropyridine (Table 3) and aryl boronic acid (Table 4) components. Using PPh2Me as the ligand, a variety of 2,3- and 2,5-dichloropyridines underwent selective monoarylation at the 2-position, affording products 2a-h with high selectivity. Notably, 2,4-dichloropyridine was an exception, resulting in an intractable mixture of mono- and diarylated products (see Supporting Information for details about low performing substrates).

Table 3.

Selective Ni-catalyzed monoarylation of dichloropyridine derivatives with (2-fluorophenyl)boronic acida

|

Reactions performed on a 0.3 mmol scale (c = 0.2 M). Combined 19F NMR yields of mono- (2) and diarylated (3) products reported with the respective ratio (2:3).

Isolation of 1.0 mmol scale reaction.

1.5 equiv of ArB(OH)2 were used. Isolated yield of monoarylated product (2) in parenthesis. [Ni] = (PPh2Me)2Ni(o-tolyl)Cl.

Table 4.

Selective Ni-catalyzed monoarylation of 1a with various chloro-containing (aryl)boronic acidsa

|

Isolated yields of reactions performed on a 0.3 mmol scale (c = 0.2 M).

1.5 equiv of ArB(OH)2 were used.

From N-Boc indole. [Ni] = (PPh2Me)2Ni(o-tolyl)Cl.

Boronic acids bearing chloride substituents at the meta and para positions also reacted in high yields, with no detectable oligomerization or over-arylation.24 Again, the combination of PPh2Me as a ligand with MeCN as a solvent is believed to accelerate displacement of the initial Ni0–π intermediate, thus limiting CTP-like polymerization of the boronic acids. For instance, monoarylated product 2j was obtained in 75% yield with our Ni/PPh2Me catalyst system (Table 4), while the Ni/PCy3 initial results afforded just 7%, largely due to competing oligomerization of the boronic acid (Scheme 2b). Other chloride-substituted (hetero)aryl boronic acids were also compatible (2i-2q), albeit affording slightly lower yields. Overall, a range of functionalities were well-tolerated, including ester, nitrile, amino, methoxy and fluoride.

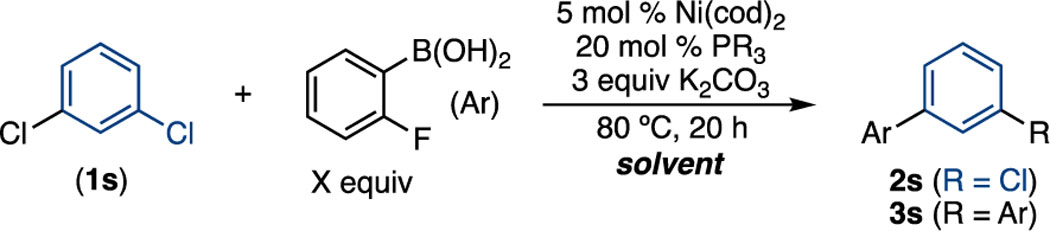

The investigations above all focus on one specific class of electrophiles: 2,x-dichloropyridines. Thus, a key outstanding question is whether the pyridine moiety is crucial for obtaining high monoarylation selectivity (since the nitrogen of the substrate could potentially play a key role in displacing the π-complex). To address this question, we undertook a final set of studies to evaluate the generality of the observed ligand and solvent effects with other dichloroarenes.25 We first examined the cross-coupling of (2-fluorophenyl)boronic acid with 1,3-dichlorobenzene (1s) using Ni(cod)2 as the catalyst (Table 5). With PPh2Me as ligand and MeCN as solvent, the monoarylated product 2s was obtained in 4 : 1 selectivity (Table 5, entry 1). Changing the solvent to THF under otherwise identical conditions afforded an erosion of selectivity to 2 : 1 (entry 2). Furthermore, moving to PCy3 as a ligand and THF as the solvent led to 1 : 8 selectivity for the diarylated product (entry 4). This selectivity increased to 1 : 13 when the stoichiometry of the boronic acid was increased from 1.1 to 2.2 equiv (compare entries 4 and 6). Overall, the results with this substrate show nearly identical ligand and solvent effects to those with 2,x-dichloropyridines, indicating the generality of these results.

Table 5.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | PR3 | solvent | ArB(OH)2 (equiv) | 2s (%) | 3s (%) | 2s : 3s |

| 1 | PPh2Me | MeCN | 1.1 | 63 | 16 | 4 : 1 |

| 2 | THF | 1.1 | 50 | 24 | 2 : 1 | |

| 3 | PCy3 | MeCN | 1.1 | 6 | 36 | 1 : 6 |

| 4 | THF | 1.1 | 6 | 48 | 1 : 8 | |

| 5 | MeCN | 2.2 | 9 | 63 | 1 : 7 | |

| 6 | THF | 2.2 | 7 | 90 | 1 : 13 | |

Reactions performed on 0.1 mmol scale (c = 0.2 M).

Yields determined by 19F NMR using trifluorotoluene as internal standard.

Finally, we scaled up the coupling of 1s and its regioisomers [1,2-dichlorobezene (1t) and 1,4-dichlorobenzene (1u)] under the optimal monoarylation conditions. As summarized in Table 6, the monoarylated products 2s-u were formed with good to excellent levels of selectivity and were isolated in 56%, 80%, and 39% yield, respectively.

Table 6.

Ni-catalyzed monoarylation of dichlorobenzene derivatives with (2-fluorophenyl)boronic acida

|

Reactions performed on a 0.3 mmol scale (c = 0.2 M). Combined 19F NMR yields of mono- (2) and diarylated (3) products reported with the respective ratio (2:3). Isolated yield of monoarylated product (2) in parenthesis. [Ni] = (PPh2Me)2Ni(o-tolyl)Cl.

In summary, a Ni phosphine catalyst has been identified for the selective Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of dichloropyridine derivatives with halogen-containing (hetero)aryl boronic acids. A ligand screen showed that PPh2Me is the optimal ligand for achieving high selectivity and yield for monoarylation with a wide range of dichloropyridine and boronic acid substrates. Several key observations were made regarding the selectivity of these reactions, including: (1) more electron-rich trialkylphosphines afford diarylation as the major product, while less-electron rich di- and triarylphosphines favor monoarylation; (2) the di- and triarylphosphines lie in a narrow range of Tolman cone angles (between 136° and 157°); (3) diarylation proceeds via intramolecular oxidative addition; and (4) the solvent (MeCN) plays a crucial role in achieving high monoarylation selectivity. Experimental and DFT studies suggest that these effects arise from the reactivity of a key intermediate: the Ni0-π complex of the mono-arylated product. With larger, more electron-rich trialkylphosphines, this π-complex undergoes intramolecular oxidative addition faster than ligand substitution by solvent, leading to selective diarylation. In contrast, with relatively small di- and triarylphosphine ligands, associative ligand substitution by MeCN is competitive with oxidative addition, resulting in selective formation of the monoarylated product. Finally, we demonstrated that these ligand and solvent effects can be applied to other dihaloarenes, affording selective monoarylation of dichlorobenzene derivatives. Overall, these studies demonstrate how the interplay of substrate, phosphine ligand, and solvent can impact selectivity in the Ni-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura couplings of polyfunctional substrates. Moving forward, we anticipate that these results will inform the development and optimization of other Ni-catalyzed C–C coupling reactions to form both small molecules and oligomers/polymers.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Corteva Agriscience is acknowledged for supporting the experimental work described herein. The DFT studies and analysis were supported by the NIH (R35GM137971 to S. R. N.). Calculations were performed on Expanse at SDSC and on Bridges2 at PSC through allocation CHE-230038 from the Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) program, which is supported by NSF grants #2138259, #2138286, #2138307, #2137603, and #2138296. The authors thank Dr. María T. Morales-Colón (currently at Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA) for helpful insights and discussions.

Funding Sources

Any funds used to support the research of the manuscript should be placed here (per journal style).

ABBREVIATIONS

- SMCC

Suzuki-Miyaura cross coupling

- TON

turn over number

- OA

oxidative addition

- TM

transmetallation

- RE

reductive elimination

- MeCN

acetonitrile

- CTP

catalyst-transfer polymerization

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

Experimental and computational details, characterization data, NMR spectra, FAIR data (including the primary NMR FID files), and Cartesian coordinates of minimum-energy calculated structures.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Scott NWJ; Ford MJ; Jeddi N;Eyles A; Simon L; Whitwood AC; Tanner T; Willans CE; Fairlamb IJSA . A Dichotomy in Cross-Coupling Site Selectivity in a Dihalogenated Heteroarene: Influence of Mononuclear Pd, Pd Clusters, and Pd Nanoparticles – the Case for Exploiting Pd Catalyst Speciation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 25, 9682–9693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Welsch ME; Snyder SA; Stockwell BR Priviledge Scaffolds for Library Design and Drug Discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2010, 14, 347–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Smith BR; Eastman CM; Njardarson JT Beyond C, H, O, and N! Analysis of the Elemental Composition of U.S. FDA Approved Drug Architectures. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 9764–9773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fang WY; Ravindar L; Rakesh KP; Manukumar HM; Shantharam CS; Alharbi NS; Qin HL Synthetic Approaches and Pharmaceutical Applications of Chloro-Containing Molecules for Drug Discovery: A Critical Review. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2019, 173, 117–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selected examples:; (a) Davies IW; Marcoux JF; Reider PJ A General [3 + 2 + 1] Annulation Strategy for the Preparation of Pyridine N-Oxides. Org. Lett 2001, 3, 209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fang AG; Mello JV; Finney NS Exploiting the Versatile Assembly of Arylpyridine Fluorophores for Wavelength Tuning and SAR. Org. Lett 2003, 5, 967–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gosmini C; Bassene-Ernst C; Durandetti M; Synthesis of Functionalized 2-Arylpyridines from 2-Halopyridines and Various Aryl Halides via a Nickel Catalysis. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6141–6146. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hagui W; Soulé JF Synthesis of 2‐Arylpyridines and 2‐Arylbipyridines via Photoredox- Induced Meerwein Arylation with in Situ Diazotization of Anilines. J. Org. Chem 2020, 85, 3655–3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almond-Thynne J; Blakemore DC; Pryde DC; Spivey AC Site-Selective Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling of Heteroaryl Halides – Understanding the Trends for Pharmaceutically Important Classes. Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 40–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Legault CY; Garcia Y; Merlic CA; Houk KN Origin of Regioselectivity in Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Polyhalogenated Heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 12664–12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Garcia Y; Schoenebeck F; Legault CY; Merlic CA; Houk KN Theoretical Bond Dissociation Energies of Halo-Heterocycles: Trends and Relationships to Regioselectivity in Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 6632–6639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Deem MC; Derasp JS; Malig TC; Legard K; Berlinguette CP; Hein JE Ring Walking as a Regioselectivity Control Element in Pd-catalyzed C-N Cross-Coupling. Nat. Commun 2022, 13, 2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selected examples:; (a) Alexander AL; Balko TW; Buysse AM; Brewster WK; Bryan K; Daeuble JF; Fields SC; Gast RE; Green RA; Irvinen NM; Lo WC; Lowe CT; Renga JM; Richburg JS; Ruiz JM; Norbert MS; Schmitzer PR; Siddall TL; Webster JD; Weimer MR; Whiteker GT; Epp JB The Discovery of ArylexTM Active and RinskorTM Active: Two Novel Auxin Herbicides. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2016, 24, 362–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang W; Wang Y; Corte JR Efficient Synthesis of 2-Aryl-6-chloronicotinamides via PXPd2-Catalyzed Regioselective Suzuki Coupling. Org. Lett 2003, 5, 3131–3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dai X; Chen Y; Garrell S; Liu H; Zhang L-K; Palani A; Hughes G; Nargund R Ligand-Dependent Site-Selective Suzuki Cross-Coupling of 3,5- Dichloropyridazines. J. Org. Chem 2013, 78, 7758–7763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Young IS; Glass A-L; Cravillion T; Han C; Zhang H; Gosselin F Palladium-Catalyzed Site-Selective Amidation of Dichloroazines. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 3902–3906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yang M; Chen J; He C; Hu X; Ding Y; Kuang Y; Liu J; Huang Q Palladium-Catalyzed C-4 Selective Coupling of 2,4-Dichloropyridines and Synthesis of Pyridine-Based Dyes for Live-Cell Imaging. J. Org. Chem 2020, 85, 6498–6508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Norman JP; Larson NG; Entz ED; Neufeldt SR Unconventional Site Selectivity in Palladium-Catalyzed Cross- Couplings of Dichloroheteroarenes under Ligand-Controlled and Ligand-Free Systems. J. Org. Chem 2022, 87, 7414–7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Norman JP; Larson NG; Neufeldt SR Different Oxidative Addition Mechanisms for 12- and 14-Electron Palladium(0) Explain Ligand-Controlled Divergent Site Selectivity. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 8822–8828. Review: Norman, J. P.; Neufeldt, S. R. The Road Less Traveled: Unconventional Site Selectivity in Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Couplings of Dihalogenated N‐Heteroarenes. ACS Cat. 2022, 12, 12014–12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Limited examples:; (a) Xi Z; Liu B; Chen W Room-Temperature Kumada Cross-Coupling of Unactivated Aryl Chlorides Catalyzed by N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Based Nickel (II) Complexes. J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 3954–3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bhat IA; Avinash I; Anantharaman G Nickel(II)- and Palladium(II)-NHC Complexes from Hydroxypyridine Functionalized C,O Chelate Type Ligands: Synthesis, Structure, and Catalytic Activity toward Kumada−Tamao−Corriu Reaction. Organometallics 2019, 38, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Miyakoshi R; Yokoyama A; Yokozawa T Catalyst-Transfer Polycondensation. Mechanism of Ni-Catalyzed Chain-Growth Polymerization Leading to Well-Defined Poly(3-hexylthiophene). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 17542–17547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Leone AK; McNeil AJ Matchmaking in Catalyst-Transfer Polycondensation: Optimizing Catalysts based on Mechanistic Insight. Acc. Chem. Res 2016, 49, 2822–2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Leone AK; Goldber PK; McNeil AJ Ring-Walking in Catalyst-Transfer Polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 7846–7850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bryan ZJ; Hall AO; Zhao CT; Chen J; McNeil AJ Limitations of Using Small Molecules to Identify Catalyst-Transfer Polycondensation Reactions. ACS Macro Lett. 2016, 5, 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hall AO; Lee SR; Bootsma AN; Bloom JWG; Wheeler SE; McNeil AJ Reactive Ligand Influence on initiation in Phenylene Catalyst-Transfer Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem 2017, 55, 1530–1535. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Fan X-H; Yang L-M Room-Temperature Nickel-Catalysed Suzuki-Miyaura Reactions of Aryl Sulfonates/Halides with Arylboronic Acids. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2011, 1467–1471. [Google Scholar]; (b) Leowanawat P; Zhang N; Safi M; Hoffman DJ; Fryberger MC; George A; Percec V trans-Chloro(1-Naphthyl)bis(triphenylphosphine)nickel(II)/PCy3 Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Aryl and Heteroaryl Neopentylglycolboronates with Aryl and Heteroaryl Mesylates and Sulfamates at Room Temperature. J. Org. Chem 2012, 77, 2885–2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dong CG; Hu QS Ni(cod)2/PCy3-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Dihaloarenes with Arylboronic Acids. Synlett 2012, 23, 2121–2125. [Google Scholar]; (d) Ramgren SD; Hie L; Ye Y; Garg NK Nickel-Catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura Couplings in Green Solvents. Org. Lett 2013, 15, 3950–3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Malineni J; Jezorek RL; Zhang N; Percec V An Idefinitely Air-Stable σ-NiII Precatalyst for Quantitative Cross-Coupling of Unreactive Aryl Halides and Mesylates with Aryl Neopentylglycolboronates. Synthesis, 2016, 48, 2795–2807. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge S; Hartwig JF Highly Reactive, Single-Component Nickel Catalyst Precursor for Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling of Heteroaryl Boronic Acids with Heteroaryl Halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 12837–12841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Standley EA; Smith SJ; Müller P; Jamison TF A Broadly Applicable Strategy for Entry into Homogeneous Nickel(0) Catalysts from Air-Stable Nickel(II) Complexes. Organometallics 2014, 33, 2012–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.To rule out a potential role of cod on the selectivity, we performed the reaction in Scheme 3 (1.1 equiv boronic acid) with Ni(cod)2 (5 mol %) and PPh2Me (20 mol %) as catalyst. This afforded 2a in 89% yield and 3a in 3% yield. These results are nearly identical to those with the Ni(II) precatalyst (88% of 2a, and 5% of 3a), suggesting that cod has a minimal impact on yield or selectivity. The Ni(II) precatalyst was used moving forward as it is a convenient-to-use, air-stable Ni source.

- 13.(a) Newman-Stonebraker SH; Smith SR; Borowski JE; Peters E; Gensch T; Johnson HC; Sigman MS; Doyle AG Univariate Classification of Phosphine Ligation State and Reactivity in Cross-Coupling Catalysis. Science 2021, 374, 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gensch T; dos Passos Gomes G; Friederich P; Peters E; Gaudin RP; Jorner K; Nigam A; Lindner-D’Addario M; Sigman MS; Aspuru-Guzik A; A Comprehensive Discovery Platform for Organophosphorus Ligands for Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 1205–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Additional Examples:; (c) Wu K; Doyle AG Parametization of Phosphine Ligands Demonstrates Enhancement of Nickel Catalysis via Remote Steric Effects. Nat. Chem 2017, 9, 779–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Newman-Stonebraker SH; Wang JY; Jeffrey PD; Doyle AG Structure−Reactivity Relationships of Buchwald-Type Phosphines in Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 19635–19648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Review:; (e) Durand DJ; Fey N Computational Ligand Descriptors for Catalyst Design. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 6561–6594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Tolman CA; Steric Effects of Phosphorus Ligands in Organometallic Chemistry and Homogeneous Catalysis. Chem. Rev 1977, 77, 313–348. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jover J; Cirera J Computational Assessment on the Tolman Cone Angles for P-ligands. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 15036–15048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.We also plotted the result versus Sterimol values (B1, B5, and L mean), but thess plots did not show definitive trends (See Table S2, and Figures S1–S2).

- 16.(a) Inada K; Miyaura N Synthesis of Biaryls via Cross-Coupling Reaction of Arylboronic Acids with Aryl Chlorides Catalyzed by NiCl2/Triphenylphosphine Complexes. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 8657–8660. [Google Scholar]; (b) Payard PA; Perego LA; Ciofini I; Grimaud L Taming Nickel-Catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling: A Mechanistic Focus on Boron-to-Nickel Transmetalation. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4812–4823. [Google Scholar]; (c) Desnoyer AN; He W; Behyan S; Chiu W; Love JA; Kennepohl P The Importance of Ligand-Induced Backdonation in the Stabilization of Square Planar d10 Nickel π–Complexes. Chem. Eur. J 2019, 25, 5259–5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Frew JJR; Clarke ML Ligand electronic effects in homogeneous catalysis using transition metal complexes of phosphine ligands. Organomet. Chem 2009, 35, 19–46. [Google Scholar]; (b) Anjali BA; Suresh CH Interpreting Oxidative Addition of Ph−X (X = CH3, F, Cl, and Br) to Monoligated Pd(0) Catalysts Using Molecular Electrostatic Potential. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 4196–4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Although we identified PPh2Me as the optimal ligand for the selective monoarylation reaction, we also included PPh3 in this study because it was used for the DFT calculations (to minimize conformational complexity), thus requiring the analogous experimental data for comparison.

- 19.(a) Chen Y; Hu B; Xu B; Zhang S; Zhou F; Li Y Co(II) and Ni(II) Complexes Incorporating N-Acetimidoylacetamidine Ligand: Synthesis and Structures. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem 2012, 57, 386–389. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bresciani G; Biancalana L; Pampaloni G; Zacchini S; Ciancaleoni G; Marchetti F A Comprehensive Analysis of the Metal-Nitrile Organo-Diiron System. Molecules 2021, 26, 7088–7011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elias EK; Rehbein SM; Neufeldt SR Solvent Coordination to Palladium can Invert the Selectivity of Oxidative Addition. Chem. Sci 2022, 13, 1618–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ring-walking from C2 to C5 was not considered for our calculations and could also play a role in selectivity. Allen and co-workers reported barriers ranging from 3.6 to 10.6 kcal/mol for Ni(dppp) [dppp = 1,3-bis(diphenylphosphino)propane] ring-walking along the edges of 2-bromopyridine. These are less than or approximately equal to our calculated values of ΔG‡ for oxidative addition and ligand substitution.; Bilbrey JA; Bootsma AN; Barlett MA; Locklin J; Wheeler SE; Allen WD Ring-Walking of Zerovalent Nickel on Aryl Halides. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2017, 13, 1706–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calculations were performed at the CPCM(MeCN)-MN15L/6–311++G(2d,p)/SDD(Ni)// CPCM(MeCN)-MN15L/6–31G(d)/LANL2DZ(Ni) level of theory.

- 23.All thermodynamic quantities were computed with the GoodVibes code (333 K) applying corrections for concentration, ([Ni] = 0.01 M, [2r] = 0.2 M, and [MeCN] = 19.1 M):; Luchini G; Alegre- Requena JV; Funes-Ardoiz I; Paton RS GoodVibes: Automated Thermochemistry for Heterogeneous Computational Chemistry Data. F1000Research 2020, 9, 291. [Google Scholar]

- 24.ortho-chloro(phenyl)boronic acids were avoided to prevent product inhibition by a (2-pyridyl) directed oxidative addition at the o–Cl bond.

- 25.An extensive literature search uncovered a single example of Ni-catalyzed selective monoarylation of a dihaloarene. In this reaction, Ni(PPh3)4 was used as a catalyst for the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of 1,2-dibromobezene with (p-tolyl)boronic acid in THF to afford a 2.5 : 1 mixture of the mono : diarylated products. The authors then optimized for diarylation and found, similar to our work, that switching to Ni(cod)2/ PCy3 led to selective diarylation. See ref. 9c for details.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.