The publication in April 2000 of the results of a clinical trial that found high fibre cereals had no protective effect against colorectal adenomas stirred up considerable media attention and shook a cherished tenet of popular health culture.1 After all, boxes of All-Bran have been assuring us for nearly two decades that they contain “at last, some news about cancer you can live with,”2 and the manufacturers of high fibre cereals have enjoyed unprecedented profits thanks to the assumption that their products provide insurance against colon cancer. What will happen to “the high fibre feeding frenzy”3 that has possessed Americans for the past 20 years now that that assumption has been challenged?

Summary points

Throughout human history, bowel irregularity has been considered to be dangerous to health

In the 19th century medical scientists formulated a theory of “intestinal autointoxication”—self poisoning from one's own retained wastes

The public became prey to marketers of anticonstipation foods, drugs, and devices; All-Bran was introduced in the early 1900s to combat autointoxication

Recent clinical evidence suggests that cereal rich in fibre does not have a protective effect against bowel cancer, but because constipation has a historic hold over the public mind, people may continue to believe that bran is protective

Constipation has always been feared

Not much, most likely. It isn't just that the epidemiologists continue to remind us that there are many observational studies of population groups that show a correlation between consumption of a bulky diet and low incidence of colorectal cancer,4 or that the gastroenterology authorities continue to recommend daily ingestion of a minimum of 30 grams of fibre.5 More important than anything the experts have to say, I would wager, is human intuition, which has seen bowel irregularity to be dangerous from as far back as health literature can be traced. The oldest complete “book” in existence is an Egyptian pharmaceutical papyrus of the 16th century BC that offers as a basic explanation of disease the notion of poisoning of the body by material released from decomposing waste in the intestines.6 The intuition was that disease is a process of internal putrefaction (as evidenced by the voiding of vomit, diarrhoea, mucus, etc) and that putrefaction can most easily be initiated by the contents of the colon, foul matter that is always undergoing a process of degeneration.

This compelling suspicion shaped medical theory for more than three millennia; the personal physician to Louis XV of France in the 18th century was merely echoing the Ebers Papyrus when he warned that disease was the result of blood turned “faeculent” by contamination with “the depraved remains of concoction” in the intestines.7 From the late 1700s onward, moreover, European and American physicians were convinced that constipation was becoming ever more common because of changes in diet, exercise levels, and pace of life associated with urbanisation. By the beginning of the 19th century, there was a medical consensus that constipation was the foremost disease of civilisation, a universal affliction in industrialised societies that engendered the full range of more serious human ailments. As a popular American health manual warned in the 1850s, “daily evacuation of the bowels is of the utmost importance to the maintenance of health”; without the daily movement, “the entire system will become deranged and corrupted.”8

Constipation and the germ theory: “autointoxication”

Surely such simplistic pathology should have been consigned to the rubbish heap once the modern germ theory of disease came in during the last quarter of the 19th century but, in truth, bacteriology only buttressed the ancient intuition that faecal decay triggers physical decay. First of all, the discovery that germs cause infection was an outgrowth of Pasteur's studies demonstrating that germs cause putrefaction of animal and vegetable material outside the body. The first practical application of Pasteur's findings, the introduction of antisepsis into surgery by Joseph Lister in the 1860s, further confirmed the germ-putrefaction connection; Lister used a caustic chemical, carbolic acid, to suppress surgical wound infection because he thought of wound inflammation as a putrefaction induced by germs, and carbolic acid was known to inhibit putrefaction in sewage. But what was the colon if not a sewage pit teeming with bacteria, a cesspit that was not being sanitised with antiseptics nor, in people with constipation, being regularly emptied? Might not its germ-infested foulness spread out somehow into the rest of the body?

A more elegant rationale for colonic corruption of the body became available in the mid-1880s, when bacteriologists came to realise that intestinal flora broke down protein residues in faeces into several compounds that showed pronounced toxicity when injected into animals. Reasoning that putrescine and cadaverine and similar ptomaines generated in the bowel could be absorbed into the bloodstream, late 19th century medical scientists formulated the theory of intestinal autointoxication, or self poisoning from one's own retained wastes. The constipated person, French physician Charles Bouchard declared, “is always working toward his own destruction; he makes continual attempts at suicide by intoxication.”9

Autointoxication not only bore the imprimatur of the most modern medical science, it met a clinical need to come up with an explanation and diagnosis for all those exasperating patients who insist that they are sick but are unable to present the physician with any clear organic disease to prove it. Thus even though autointoxication was, to paraphrase Pudd'nhead Wilson, nothing more than constipation with a college education, it became its era's catchall diagnosis, the pigeonhole into which cases of headache, indigestion, impotence, nervousness, insomnia, or any number of other functional disorders of indeterminate origin could be placed. The diagnosis was not restricted to such relatively benign complaints, however, for heart disease and cancer and other deadly ailments did not always have obvious causes either. Given enough time, it seemed, toxins absorbed from the torpid bowel could wreak just about any degree of havoc anywhere in the body. Indeed, from 1900 into the 1920s autointoxication was regarded by much of the medical profession and most of the public as the most insidious disease of all, since it was, in essence, all diseases. In books such as The Conquest of Constipation, The Lazy Colon, and Le Colon Homicide physicians on both sides of the Atlantic warned that the contents of the colon were “a burden, fermenting, decomposing, putrefying, filling the body with poisonous substances” and creating “sewer-like blood”10; that autointoxication “is the cause of ninety per cent of disease”; and that “constipation shortens life.”11

Prevention and treatment of autointoxication

Physicians were also generous with advice on preventing constipation, but recommendations to eat more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains; to be more active physically; and always to respond promptly to nature's morning call to evacuate seemed to many people to require more self discipline and sacrifice than they cared to exercise. The public, anxious about autointoxication, thus fell easy prey to all manner of marketers of anticonstipation foods, drugs, and devices. All-Bran was introduced in the early 1900s precisely to combat autointoxication, as were any number of other bran cereals such as the so subtly named DinaMite. Yeast was a heavily promoted dietary preventive of constipation, and yogurt acquired its reputation as a health food when recommended in the first decade of the century to forestall autointoxication.

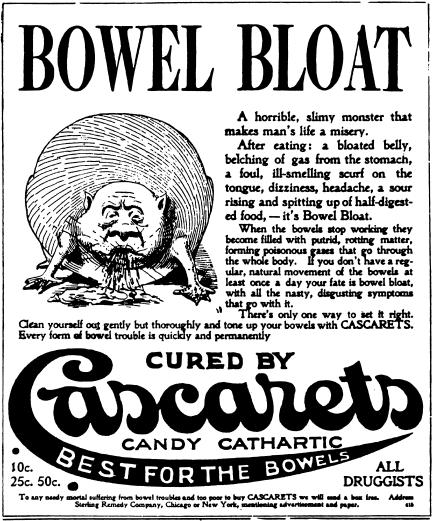

Still more popular were laxatives. The 1920s and '30s were the golden age of purgation as literally hundreds of brands of bowel cleansers competed for consumer dollars with lurid advertisements such as the Cascarets warning of the dangers of “Bowel Bloat” (fig 1). Phenolphthalein, introduced as a cathartic in 1900, quickly claimed the position of best selling of all laxatives on the strength of its marketing campaign to rescue innocent children from the clutches of autointoxication. Indeed, the manufacturers of brands running from best selling Ex-Lax to the onomatopoeic Zam Zam laid down a relentless advertising barrage aimed at frightening parents into giving their children daily doses of chocolate-coated or otherwise pleasantly disguised phenolphthalein, making it sound as if the chief source of paediatricians' income must be epidemic laxative deficiency.

Figure 1.

Scare tactics were used by manufacturers of purgatives

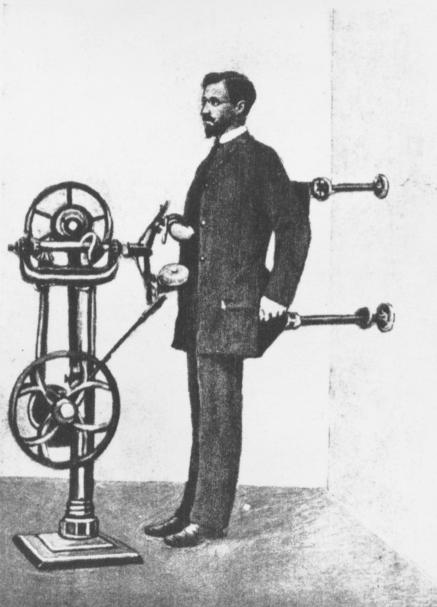

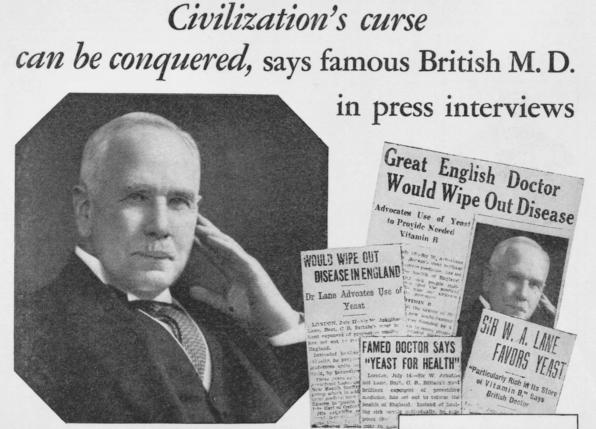

A horde of device salesmen swept over the land as well, peddling an astounding collection of merchandise: enema and colonic irrigation equipment, abdominal support belts, abdominal massage machines (fig 2), electrical stimulators, rectal dilators (fig 3), and so on and on. Not the least intimidating of the cures for autointoxication was surgery, colectomy to be precise, popularised by the renowned surgeon of London's Guy's Hospital, Sir William Arbuthnot Lane (fig 4). Between 1900 and 1920, Lane extirpated the colons of hundreds of constipates, maintaining that his streamlining of the human “drainage scheme” was “the most satisfactory result of surgery known to us at the present time.”12

Figure 2.

An abdominal massage machine

Figure 3.

This advertisement was carried in “Nature's Path” in 1938

Figure 4.

Sir William Arbuthnot Lane appeared in advertisements promoting yeast for health

Constipation related to “civilisation”

A number of experimental studies in the 1910s cast doubt on the possibility of bowel toxins leaching into the circulation, and autointoxication slowly faded from professional acceptance during the 1920s. Fear of constipation continued to be exploited by laxative and other manufacturers, of course, but more pertinent was Arbuthnot Lane's persistent belief in constipation as a disease exclusive to urban, industrial civilisation—as, in fact, “the disease of diseases,” as he dubbed it, “the cause of all the hideous sequence of maladies peculiar to civilisation.”13 Lane had a distinctive theoretical argument for identifying constipation as a disease of civilisation, explaining how the living habits of people in the developed world distorted the colon's anatomy in a way not suffered by “savage races.”14 More important in the long run, however, was the epidemiological justification for his contention that constipation was the true white man's burden. Although he did none of the sophisticated statistical comparisons of disease incidence in developed and developing countries that became the norm in the second half of the 20th century, he read widely in the publications of European physicians practising in India and in African nations, and he became convinced that both constipation and a number of ailments common to Europe and America existed at very low levels among “uncivilised” populations. Lane was particularly adamant that colon cancer was so rare in pre-industrial peoples because their bowels moved frequently due to a diet of whole grain cereal foods: “the whiter your bread,” he liked to say, “the sooner you're dead.”15

The dietary fibre hypothesis and “Western diseases”

One sees in Lane the germs of the dietary fibre hypothesis and the concept of “Western diseases” developed most notably by English surgeon Denis Burkitt in the 1970s and '80s. Burkitt told me in conversation that he was unaware of Lane's work until he was well along in the formulation of his own ideas about fibre. Yet a link exists none the less, as Burkitt was inspired by the “saccharine disease” theory of British naval surgeon T L Cleave, who drew on the observations of Sir Robert McCarrison, a British physician in India during Lane's day. McCarrison's reports of the rarity of colon cancer, appendicitis, and gastric and duodenal ulcer among the grain-eating Hunza of northern India were used by Lane as the cornerstone of his theory. Burkitt too saw that “constipation is the commonest Western disease,”16 and his exhortations to Westerners to consume more dietary fibre to ward off colon cancer and other ailments of industrialised societies, an obituarist observed, “was to change the breakfast tables of the western world.”17

Conclusion

I would guess that, given the historic hold of constipation on the public mind, most of those tables will stay changed no matter how many clinical trials deny that Burkitt and Lane were right about bran and colon cancer. People instinctively appreciate the wisdom of an elderly Scottish physician who used to consult with another Guy's Hospital surgeon, Sir Astley Cooper, in the early 1800s. “Weel, Mister Cooper,” he would say just before entering the sick room, “we ha' only twa things to keep in meend, and they'll searve us for here and herea'ter; one is always to have the fear of the Laird before our ees, that'll do for herea'ter; and the t'other is to keep your booels open, and that will do for here.”18

Figure.

This article originally appeared in the December issue of wjm, the Western Journal of Medicine, currently online at www.ewjm.com

Acknowledgments

This subject is discussed at much greater length in Whorton JC. Inner Hygiene: Constipation and the Pursuit of Health in Modern Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000). The photographs are reproduced from that book.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Alberts DS, Martinez ME, Roe DJ, Guillen-Rodriguez JM, Marshall JR, van Leeuwen JB, et al. Lack of effect of a high-fiber cereal supplement on the recurrence of colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1156–1162. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004203421602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foltz K. Policing the health ads. Newsweek 1984 Nov 26:75.

- 3.Gilman M. Fiber mania. Psychology Today 1989 December:33.

- 4.Byers T. Diet, colorectal adenomas, and colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1206–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004203421609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y. AGA technical review: impact of dietary fiber on colon cancer occurrence. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1235–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebbell BB, editor. The Papyrus Ebers. Copenhagen: Levin and Munksgaard; 1937. pp. 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieutaud J. Synopsis of the practice of medicine. Philadelphia: Parker; 1816. p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Root HK. The people's medical lighthouse. New York: Ranney; 1856. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchard C. Lectures on auto-intoxication in disease or self-poisoning of the individual. Philadelphia: Davis; 1906. p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilik SE. The trainer's bible. New York: Athletic Trainer's Supply; 1928. p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stemmerman W. Intestinal management for longer, happier life. Asheville, NC: Arden; 1928. p. 25. , 28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane WA. An address on chronic intestinal stasis. BMJ. 1913;ii:1126. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.2528.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane WA. Blazing the health trail. London: Faber and Faber; 1929. p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lane WA. The operative treatment of chronic constipation. London: Nisbet; 1909. pp. 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lane WA. Against white bread. JAMA. 1924;83:1179. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burkitt DP, Trowell HC, editors. Western diseases: their emergence and prevention. London: Arnold; 1960. p. 427. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fergusson A. D P Burkitt [obituary] BMJ. 1993;306:996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper AP. The lectures of Sir Astley Cooper. Boston: Lilly and Wait; 1831. p. 56. [Google Scholar]