Abstract

Ischemic stroke is a major cause of disability and death worldwide, and its management requires urgent attention. Previous studies have shown that vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) exerts neuroprotection in ischemic stroke by inhibiting neuroinflammation and apoptosis. In this study, we evaluated the timing for VNS intervention in ischemic stroke, and the underlying mechanisms of VNS-induced neuroprotection. Mice were subjected to transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) for 60 min. The left vagus nerve at cervical level was exposed and attached to an electrode connected to a low-frequency electrical stimulator. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) was given for 60 min before, during and after tMCAO (Pre-VNS, Dur-VNS, Post-VNS). Neurological function was assessed 24 h after reperfusion. We found that all the three VNS significantly protected against the tMCAO-induced injury evidenced by improved neurological function and reduced infarct volume. Moreover, the Pre-VNS was the most effective against the ischemic injury. We found that tMCAO activated microglia in the ischemic core and penumbra regions of the brain, followed by the NLRP3 inflammasome activation-induced neuroinflammation, which finally triggered neuronal death. VNS treatment preserved α7nAChR expression in the penumbra regions, inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation and ensuing neuroinflammation, rescuing cerebral neurons. The role of α7nAChR in microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation in ischemic stroke was further validated using genetic manipulations, including Chrna7 knockout mice and microglial Chrna7 overexpression mice, as well as pharmacological interventions using the α7nAChR inhibitor methyllycaconitine and agonist PNU-282987. Collectively, this study demonstrates the potential of VNS as a safe and effective strategy to treat ischemic stroke, and presents a new approach targeting microglial NLRP3 inflammasome, which might be therapeutic for other inflammation-related diseases.

Keywords: ischemic stroke, vagus nerve stimulation, microglia, NLRP3, neuroinflammation, α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

Introduction

Stroke is the leading cause of disability and death globally, resulting in an increasing economic burden [1]. Ischemic stroke, which occurs due to a blockage in the artery that supplies blood to the brain, represents the most prevalent form of stroke [2]. Currently, management of ischemic stroke involves intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular thrombectomy, which aim to restore blood flow to the brain. However, these interventions are time-limited and may lead to ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, exacerbating neurological deficits and causing secondary brain damage. Therefore, it is imperative to deepen our understanding of the pathogenesis of I/R injury to identify effective therapeutic targets.

Microglia-mediated neuroinflammation is the main contributor to I/R injury during ischemic stroke [3, 4]. Numerous studies have shown that the NOD-like receptor family, NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is activated in microglia in response to ischemic stroke, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [5, 6]. For this reason, targeting microglial NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation has gained attention as a potential therapeutic approach for ischemic stroke. Preclinical studies have verified that inhibition of microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation effectively alleviated cerebral I/R injury [5, 7, 8]. However, no available interventions or drugs targeting microglial NLRP3 inflammasome are currently used in clinic for ischemic stroke patients. The translational gap may be attributed to the improper interventions or severe side effects of potential drugs, which are difficult to achieve in stroke patients. Safe and effective strategies targeting microglial NLRP3 inflammasome are urgently needed to treat stroke.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) was first approved for the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy [9]. Owning to safe and efficacy, VNS has been applied for treatments of other brain diseases, including stroke [10]. Emerging studies have demonstrated that VNS is neuroprotective for cerebral I/R injury in animal models through inhibition of neuroinflammation and apoptosis [10, 11]. More importantly, VNS paired with rehabilitation improves arm impairment of ischemic stroke patients [12]. Accordingly, VNS could be a promising strategy for stroke therapy. Nevertheless, evaluation of the timing for VNS intervention in ischemic stroke is lacking, and the underlying mechanism involved in VNS-mediated inhibition of microglial NLRP3 inflammasome remains unclear.

In this study, we performed VNS intervention at 3 different time periods: before, during and after ischemic occlusion to evaluate the neuroprotective effect of VNS on cerebral I/R injury. Additionally, we examined the effect of VNS treatment on 4 types of inflammasomes and 9 subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) in the context of ischemic stroke. By manipulating α7nAChR genetically (Chrna7 knockout mice and microglial Chrna7 overexpression mice) and pharmacologically (α7nAChR inhibitor methyllycaconitine and α7nAChR agonist PNU-282987), we demonstrate that VNS pretreatment effectively protects against cerebral I/R injury through α7nAChR-dependent inhibition of microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Our work provides new insights into VNS treatment for ischemic stroke as well as new targets for inactivation of microglial NLRP3 inflammasome.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL/6 male mice weighing 22 ± 2 g were obtained from the Animal Resource Center of the Faculty of Medicine, Nanjing Medical University. Chrna7 knockout mice (male, weighing 22 ± 2 g, C57BL/6 background) were gifts from Prof Yi Fan’s lab purchased from Jackson lab [13]. All experiments conducted on mice followed the guideline of the Animal Protection and Use Committee of Jiangsu Experimental Animal Association, and were approved by the Animal Protection and Ethics Committee (IACUC) of Nanjing Medical University. Mice were housed in a standard specific pathogen-free environment (12 h light-dark-cycle; 23 ± 1 °C; 50% ± 5% humidity) with free access to food and water.

Genotyping for Chrna7 knockout mice

Genotyping was performed for Chrna7 knockout mice using specific primers. The primer sequences used were as follows in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers for genotyping.

| Primer type | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| Common | CCTGGTCCTGCTGTGTTAAACTGCTTC |

| WT reverse | CTGCTGGGAAATCCTAGGCACACTTGAG |

| Mutant reverse | GACAAGACCGGCTTCCATCC |

PCR was carried out with these primers. In the genotyping analysis of the Chrna7 gene, the presence of the wild-type allele was indicated by the appearance of a band at 750 bp. The heterozygous allele was characterized by the presence of bands at both 440 bp and 750 bp. The homozygous allele exhibited a band exclusively at 440 bp.

Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model

The transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) was conducted using the intraluminal filament technique previously described [14]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane, and the common carotid artery (CCA), external carotid artery (ECA), and internal carotid artery (ICA) were exposed surgically through mid-line neck incisions. The CCA was temporarily blocked using microvascular clip, and the nylon monofilament (0.18 ± 0.01 mm, L1800, Guangzhou Jialing Biotechnology, Guangzhou, China) was inserted into the ICA through the ECA until it reached the middle cerebral artery (MCA). The nylon monofilament was pulled out for reperfusion after 60 min of occlusion. Regional cerebral blood flow was measured using the MoorFLPI full-field laser perfusion imager (MoorFLPI-2, Gene&I, Beijing, China), and mice with a RCBF reduction >70% of baseline were included for further study. Sham-operated mice received the same anesthesia and surgical procedures without the MCA occlusion. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C with a heating pad during the surgery. Mice were placed separately in cages under a heating lamp to keep the temperature at 37 °C during recovery for 2 h observation. After recovery, mice were returned to cages with free access to food and water. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after reperfusion following neurological function assessment.

Methyllycaconitine citrate (MLA), an antagonist of α7nAChR, was purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE, HY-N2332A). Mice were administered MLA at 2.5 mg/kg intraperitoneally 1 h before tMCAO model.

Vagus nerve stimulation

A small incision was made on the left ventral side of the neck adjacent to the midline to approach the left vagus nerve at the neck level. We performed blunt dissections of subcutaneous fat, salivary glands, sternoid bone, sternocleidomastoid muscles, and incised carotid sheaths to expose the vagus nerve. Separate 5 mm-long segment of the left vagus nerve and attach it to the electrode. To ensure good contact between the electrodes and the vagus nerve, an ohmic table was used. Connect the ohmic probe to the electrode and electrical stimulator, and then attach the electrode to the vagus nerve. The electrode consists of a pair of Teflon-coated silver hooks. To avoid short circuits, dry with gauze. Low-frequency electrical stimulator (ES-420; ITO Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation) was used, and the parameters were 0.5 min ON and 4.5 min OFF, with each ON period consisting of 0.5 millisecond pulses at 0.5 mA, 20 Hz. The sham and tMCAO groups were operated the same as VNS group without electrical stimulation. The PowerLab data acquisition system (ADINSTRUMENTS) collected the electrical signals, and the changes in the electrocardiogram were observed during VNS stimulation signal output and cessation.

Neurological function assessment

The modified neurological severity score (mNSS) was used to assess neurological function of mice 24 h after the tMCAO model, as described previously [15]. Briefly, mNSS rates neurological functioning on a scale of 14-point, including motor, sensory, balance, and reflex tests. To reduce bias in the assessment, examiner was blinded to the mice being tested. Scores were recorded for each mouse with higher scores indicating greater neurological deficits.

Measurement of infarct volume

2,3,5-triphenyltetrazole chloride (TTC) staining was used to visualize and measure the infarct volume as previously described [16]. Briefly, 2% TTC (T8877‐25 G, Sigma, Shanghai, China) was dissolved in PBS, and brain slices were incubated in TTC solution for 15 min at 37 °C, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde fixation overnight. Photographs were taken and the volume of infarction was measured and analyzed using ImageJ software. A correction for edema was made according to the following equation: (volume of contralateral hemisphere − volume of non-lesioned area in ipsilateral hemisphere)/volume of contralateral hemisphere × 100%. The investigator was blinded to sample allocation and data analysis.

Stereotaxic injection of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV)

C57BL/6 mice underwent anesthesia using isoflurane and were securely positioned on a stereotaxic instrument. Pre-procedural measures included head shaving and iodine disinfection of the targeted area. An incision was made in the skin to reveal the bregma point. BrainVTA synthesized the adeno-associated virus (rAAV-CX3CR1-Chrna7-2A-EGFP-WPRE-hGH PolyA, Transcript ID: NM_007390.3), which facilitated specific overexpression of Chrna7 in microglia, alongside a control AAV. The AAVs were injected into the left somatosensory motor cortex at a rate of 1 μL/5 min, with a total volume of 1.5 μL. The injection site coordinates were 1.06 mm caudal to the bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to the midline, and 0.55 mm ventral to the dura. To prevent viral backflow, the needle was retained in place for 10 min before being slowly withdrawn over approximately 10 min. The incision was sutured, and erythromycin ointment was applied to prevent infection. The mice were then subjected to standard rearing conditions for a duration of 3 weeks to facilitate viral expression.

Western blotting

Protein lysates from penumbra area of mice were obtained using RIPA lysis buffer and quantified by BCA method according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). The protein electrophoresis was conducted by SDS‐PAGE, and proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. The PVDF membranes were then blocked with milk at room temperature for 2 h, and incubated with primary antibodies for 12 h at 4 °C. After washing the membranes three times by TBST, secondary antibodies incubation was conducted for 2 h. The protein bands were captured by ECL method and analyzed using the Image Quant™ LAS 4000 imaging system (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The proteins grayscales were quantified by ImageJ software. The primary antibodies used in this study included anti-α7nAChR (1:500, Santa Cruz, sc-58607), anti-NLRP3 (1:1000, AdipoGen, AG-20B-0014-C100), anti-NLRP4 (1:1000, ABclonal, A7382), anti-pro-caspase-1 (1:1000, AdipoGen, AG-20B-0042-C100), anti-caspase-1 (1:1000, AdipoGen, AG-20B-0042-C100), anti-pro-IL-1β (1:250, Sigma, I-3767), anti-IL-1β (1:250, Sigma, I-3767), anti-ASC (1:1000, AdipoGen, AG-25B-0006), anti-p-NF‐κB (p-p65) (1:1000, Cell Signaling, Ser536), anti-GAPDH (1:5000, Proteintech, 6000‐1‐lg), and anti-Tubulin (1:5000, Proteintech, 10004491). The secondary antibodies used in this study included HRP-conjugated anti-Rabbit IgG (1:5000, YEASEN, 33101ES60), HRP-conjugated anti-Mouse IgG (1:5000, YEASEN, 33913ES60647), and HRP-conjugated anti-Goat IgG (1:5000, Bioss, bs-0294R-HRP).

Quantitative real‐time PCR

According to the manufacturer, total RNA from penumbra area of mice was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Reverse transcription of total RNA was carried out using TaKaRa Master Mix (TaKaRa, Japan). The primers were purchased and validated from Genescript (Nanjing, China). Real-time qPCR was performed on a StepOnePlus instrument using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). All independent experiments were performed using GAPDH as the endogenous control and data were analyzed using the 2 −ΔΔCT method. Primer sequences were listed in Table 2. Primers for genes encoding nAchRs were purchased from GeneCopoeiaTM: Chrna2 (MQP038106), Chrna3 (MQP038266), Chrna4 (MQP031242), Chrna5 (MQP126183), Chrna6 (MQP032530), Chrna7 (MQP026490), Chrnb2 (MQP090776), Chrnb3 (MQP090399), Chrnb4 (MQP039770).

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Genes | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Nlrp1 | GCTGAATGACCTGGGTGATGGT | CTTGGTCACTGAGAGATGCCTG |

| Aim2 | AGGCTGCTACAGAAGTCTGTCC | TCAGCACCGTGACAACAAGTGG |

| Nlrp3 | TCACAACTCGCCCAAGGAGGAA | AAGAGACCACGGCAGAAGCTAG |

| Nlrc4 | CTCACCACGGATGACGAACAGT | TGTCATCCAGTATGAGTCTCTCG |

| Gapdh | AACGACCCCTTCATTGAC | TCCACGACATACTCAGCAC |

Immunohistochemical staining

Brain sections were selected and rinsed three times in PBS. To remove endogenous peroxidases from the tissue, the sections were incubated in 3% H2O2 in the dark for 15 min. After three rinses in PBS, the sections were blocked with a solution of 0.3% PBST (PBS containing 0.3% Triton-X 100) at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, including anti-Iba1 (1:500, Wako, 019-19741) and anti-GFAP (1:800, Millipore, MAB360). Following three rinses in PBS, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h. After three additional rinses in PBS, DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine) was used for staining. The sections were mounted, dehydrated with a series of ethanol washes (70% ethanol for 30 s, 80% ethanol for 30 s, 95% ethanol for 30 s, 100% ethanol I for 60 s, 100% ethanol II for 60 s, xylene I for 2 min, xylene II for 5 min), and then coverslipped. The dried slides were examined and imaged using a light microscope.

Immunofluorescence staining

For brain slices, multicolor immunofluorescence staining was used according to the instruction of the commercial kit (HISTOV, NECC450). Briefly, brain slices were washed by PBS, followed by 3% H2O2 to remove the catalase. Then, the brain slices were incubated in the blocking solution for 1.5 h, and the primary antibody was incubated for 24 h. After wash out, the secondary antibody was incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h. Then, dyes were incubated. The same procedure was performed for next target, and nucleus was stained by Hoechst lastly. The primary antibodies included anti-NeuN (1:50, Millipore, MAB377), anti-Iba1 (1:500, CST, 17198), anti-GFAP (1:800, Millipore, MAB360), anti-ASC (1:200, AdipoGen, AG-25B-0006), anti-caspase1 (1:200, AdipoGen, AG-20B-0042-C100), anti-NLRP3 (1:200, AdipoGen, AG-20B-0014-C100). Images were captured using a microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed by ImageJ software.

For cells, 4% paraformaldehyde was used for fixation, followed by blocking with 3% BSA solution containing 0.1% Triton-X 100 for 1 h at room temperature. Then, cells were incubated with primary antibody anti-NF‐κB (p-p65) (1:200, Abcam, ab32536), anti-MAP2 (1:200, ThermoFisher, PA5-17646) at 4 °C overnight. Anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:1000, ThermoFisher, 35552) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature after wash out. Nucleus was stained with DAPI for 15 min. Images were taken using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM710, Jena, Germany).

Cell culture and treatment

BV2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, C11995500BT, ThermoFisher) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10100147, ThermoFisher), 1% penicillin (100 U/mL)/streptomycin (100 mg/mL) in an incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were pretreated with PNU-282987 (PNU, MCE, HY-12560A) at 0.1 μM for 1 h followed by oxygen‐glucose deprivation and reperfusion (OGD/R) model or LPS (100 ng/mL, 5.5 h)+ATP (5 mM, 0.5 h) model.

PC12 cells were cultured in the same condition as BV2 cells, and then replaced with conditioned medium collected from BV2 cells in the LPS + ATP model. Cell viability assay and flow cytometry assay were performed 24 h after PC12 cells cultured in the conditioned medium.

Primary neurons were obtained from E17 mice following previously established protocols [17]. In brief, the cortex was meticulously dissected in ice-cold PBS, and trypsin (0.25%, 12 min at 37 °C) was used for dissociation. The neurons were then seeded onto poly-d-lysine-treated culture plates in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Subsequently, the cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 4 h, following which the media were replaced with serum-free Neurobasal/B27/glutamine media. Half of the medium was refreshed every 3 days. Experiments were conducted on neurons that had been cultured for 12 to 14 days in vitro. These neurons were exposed to conditioned medium collected from microglia in the LPS + ATP model. Morphology analysis was carried out using ImageJ ANDI (automated neurite degeneration index) Macro as described [18] 24 h after treatment with the conditioned medium.

Primary microglia were obtained from astrocyte cultures as previously described [17]. Briefly, the cortex of neonatal mice was carefully isolated from the meninges and basal ganglia. The tissues were dissociated using 0.25% trypsin at 37 °C and the reaction was halted by adding DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were then seeded onto flasks, and the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium after 24 h. Subsequently, the media were refreshed every 3 days. After a 14-day culture period, microglia were separated from the astrocytes by subjecting the flasks to shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h at 37 °C. The detached microglia were plated and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 30 min. Unbound cells were removed by changing the culture medium. Microglia were pre-treated with PNU-282987 (PNU, MCE, HY-12560A) at a concentration of 0.1 μM for 1 h, followed by exposure to the LPS (100 ng/mL, 5.5 h) + ATP (5 mM, 0.5 h) model. Subsequently, the conditioned medium was collected.

Oxygen‐glucose deprivation and reperfusion model

The oxygen‐glucose deprivation and reperfusion (OGD/R) model was performed as described previously [19]. In brief, before OGD/R, BV2 cells were cultured in DMEM (C11995500BT, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS in an incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. During OGD, cells were incubated in glucose‐free DMEM (Life Technologies, 11966‐025, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) with deoxygenated condition (95% N2 and 5% CO2) for 4 h. After OGD, the glucose‐free DMEM was replaced with complete medium, and cells were transferred to a normoxic incubator for 24 h.

Cell viability assay

The PC12 cell viability was measured by cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8 Kit, c0037, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). In brief, PC12 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and treated with conditioned medium collected from BV2 cells. After 24 h, 10 μL CCK-8 reagent was added into each well and incubated for 4 h. Cell viability was reflected by the absorbance at 450 nm detected by the Multiskan Spectrum (ThermoFisher Scientific).

ELISA assay

To determine the level of released IL-1β, conditioned medium from BV2 cells was collected and analyzed using commercial ELISA kits (Jiancheng Bioengineering Technology, Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry assay

PC12 cells were washed and trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution. Cells were collected by centrifugation, and incubated with AnnexinV-FITC (AV) and Propidium iodide (PI) from the commercial kit (Vazyme, A211-02) for 15 min in the dark at room temperature. Then, cells were added with binding buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS Calibur, BD, USA). At least 10,000 events per sample were collected for data analysis.

Bioinformatics analysis

Transcriptomic profiling of tMCAO-induced stroke in mouse brain tissue

The dataset (GSE98319) containing transcriptomic profiles of mouse brain tissue subjected to tMCAO-induced stroke was obtained from the publicly available GEO database. The tMCAO method was utilized to induce stroke in mice, and brain tissue samples were collected 12 h post-surgery for microarray analysis. The Arraystar Mouse V3B platform (GPL19286) was employed, comprising of 3 sham-operated control samples and 3 stroke samples. The raw CEL files of the dataset were processed using the oligo package in R to convert them into an expression matrix, which was further normalized using the RMA method. The data table specific to the GPL19286 platform was downloaded, and probe IDs were converted to gene symbols. In cases where multiple probes corresponded to the same gene, the average expression value was calculated. The expression matrix, transformed into gene symbols, was visualized as a clustered heatmap using the pheatmap package in R. Differential gene identification and selection between the tMCAO group and sham-operated control group brain tissues were performed using the limma and dplyr packages in R, with a significance threshold set at P < 0.05 and |log fold change (FC)| >1.3.

Functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes

To investigate the functional implications of the differentially expressed genes, the online tool DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp; v2022q3) was employed for functional enrichment analysis. This analysis was based on the Gene Ontology (GO) database and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. The results of the enrichment analysis were visualized using the ggplot2 package in R, and a significance threshold of P < 0.05 was applied to identify enriched functional categories and pathways.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.0 software. The unpaired Student’s t test was utilized to compare a single variable in two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare one variable in three or more groups, with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test used for post-hoc analysis. For comparisons of two independent variables, two-way ANOVA was used, followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. The Mean with 95% CI were plotted on graphs with individual data points shown. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. The in vitro experiments utilized more than three biological replicates and two technical replicates, and detailed information can be found in the figure legends.

Results

VNS treatment protects against I/R injury in the tMCAO mouse model

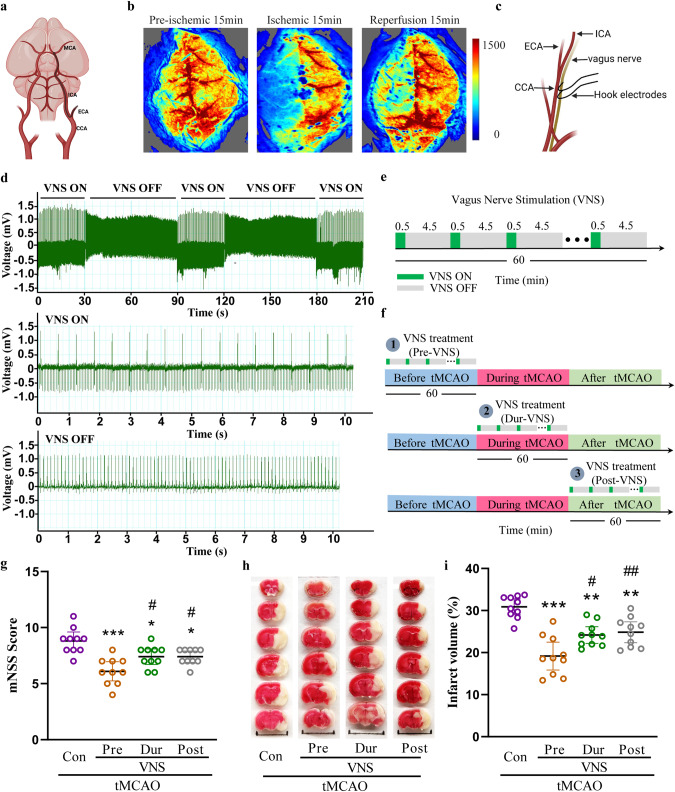

The transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) model was performed in this study (Fig. 1a), and the cerebral blood flow was monitored by the laser Doppler blood flow meter. The ipsilateral cerebral blood flow was dramatically reduced upon occlusion of the middle cerebral artery, and partially recovered after reperfusion, suggesting successful generation of the tMCAO model (Fig. 1b). Vagus nerve stimulation was conducted using an electrode placed on the nerve at the cervical level (Fig. 1c). The heart rate was significantly decreased upon stimulation and restored upon withdrawal of the stimulation, indicating successful stimulation of the vagus nerve (Fig. 1d). Next, we explored the effect of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) on ischemic stroke injury. VNS was conducted for 60 min with 0.5 min on and 4.5 min off in every 5 min (Fig. 1e). In the tMCAO model, VNS treatment was performed before tMCAO (Pre-VNS), during tMCAO (Dur-VNS), and after tMCAO (Post-VNS) (Fig. 1f). Intriguingly, each of the three VNS treatments protected against the tMCAO-induced injury by improving neurological function (Fig. 1g) and reducing infarct volume (Fig. 1h, i). Moreover, the Pre-VNS treatment was the most effective against the injury and was further investigated in this study.

Fig. 1. VNS treatment improves neurological function and reduces infarct volume in the tMCAO mouse model.

a Illustration of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. b Reduction in regional cerebral blood flow in the tMCAO model measured by the MoorFLPI full-field laser perfusion imager. c Illustration of vagus nerve stimulation. d Electrocardiograph showing a reduction in heart rate upon VNS treatment. e Illustration of VNS intervention in 60 min. f Illustration of VNS treatment timing in the tMCAO model. g mNSS score of tMCAO mice showing the improvement of VNS treatment in neurological function, n = 10. h, i TTC staining and quantitative analysis showing a reduction in infarct volume by VNS treatment. Scale bar: 1.0 cm, n = 10, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Con group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. Pre-VNS group.

VNS treatment ameliorates neuronal death through inhibition of microglia-mediated inflammation

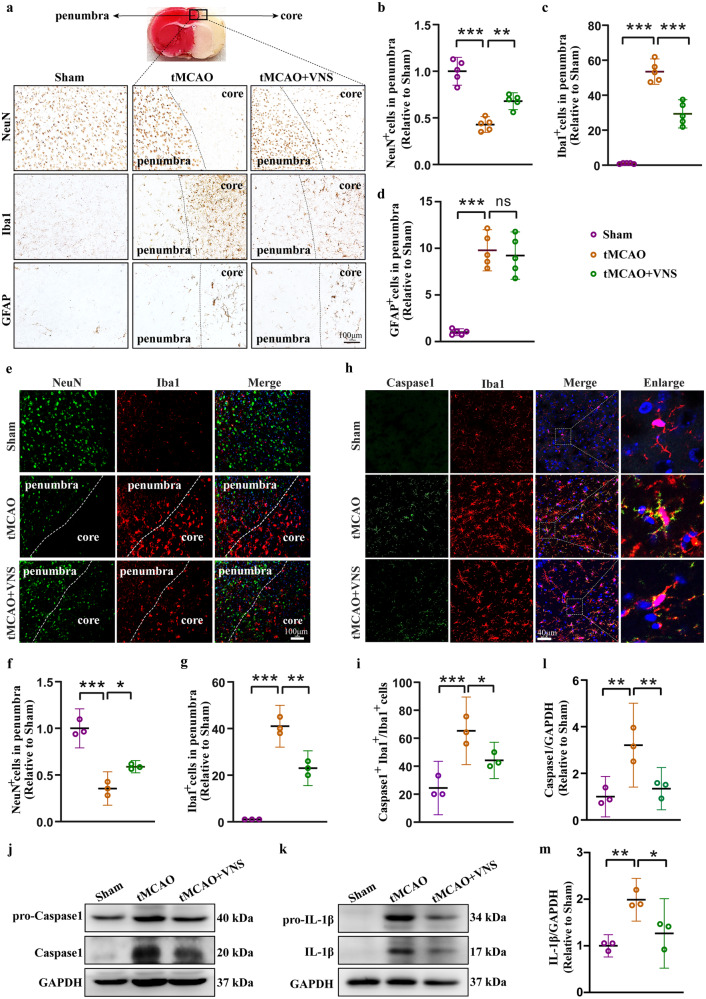

We then investigated the potential mechanism involved in VNS-mediated neuroprotection in ischemic stroke. Immunohistochemical staining of NeuN, Iba1, and GFAP was performed to assess neuronal loss, microglial activation, and astrocyte activation in the core and penumbra regions of tMCAO mice. The results demonstrated a significant decrease in neurons and a substantial increase in microglia and astrocytes in the tMCAO mice. However, VNS treatment effectively rescued neuronal loss and suppressed the increase in microglia, while it had no effect on the number of astrocytes in the penumbra region of tMCAO mice (Fig. 2a–d). Immunofluorescence staining of NeuN and Iba1 further confirmed these findings (Fig. 2e–g). These observations suggest that the neuroprotective effects of VNS in ischemic stroke may be attributed to the inactivation of microglia rather than astrocytes.

Fig. 2. VNS treatment rescues neuronal loss via inhibiting microglia activation-induced neuroinflammation.

a–d Representative immunohistochemical images of NeuN, Iba1, and GFAP, and quantification of NeuN positive, Iba1 positive, and GFAP positive cells in the penumbra region showing the rescue of neuronal death and inhibition of microglia activation by VNS treatment, n = 5, scale bar: 100 μm. e–g Representative immunofluorescence images of NeuN and Iba1, and quantification of NeuN positive and Iba1 positive cells in the penumbra region showing the rescue of neuronal death and inhibition of microglia activation by VNS treatment, n = 3, scale bar: 100 μm. h, i Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of Caspase1 and Iba1 positive cells showing the inhibition of microglial inflammasome activation by VNS treatment, n = 3, scale bar: 40 μm. j–m Representative blots and quantitative analyses showing the reduction in the expression of caspase1 and IL-1β by VNS treatment, n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns no significance.

Given the crucial role of microglia in neuroinflammation, we investigated the activation of inflammasomes, which are protein complexes involved in mediating inflammatory responses in microglia [20]. Our analysis revealed a significant elevation of Caspase 1, an indicator of inflammasome assembly, in microglia, which was subsequently reduced by VNS treatment (Fig. 2h, i). More importantly, VNS treatment effectively attenuated the production of mature Caspase 1 and IL-1β, key markers of inflammasome activation, in the penumbra area (Fig. 2j–m). These findings indicate that the neuroprotective effects of VNS treatment in ischemic stroke are associated with the inhibition of inflammasome activation in microglia.

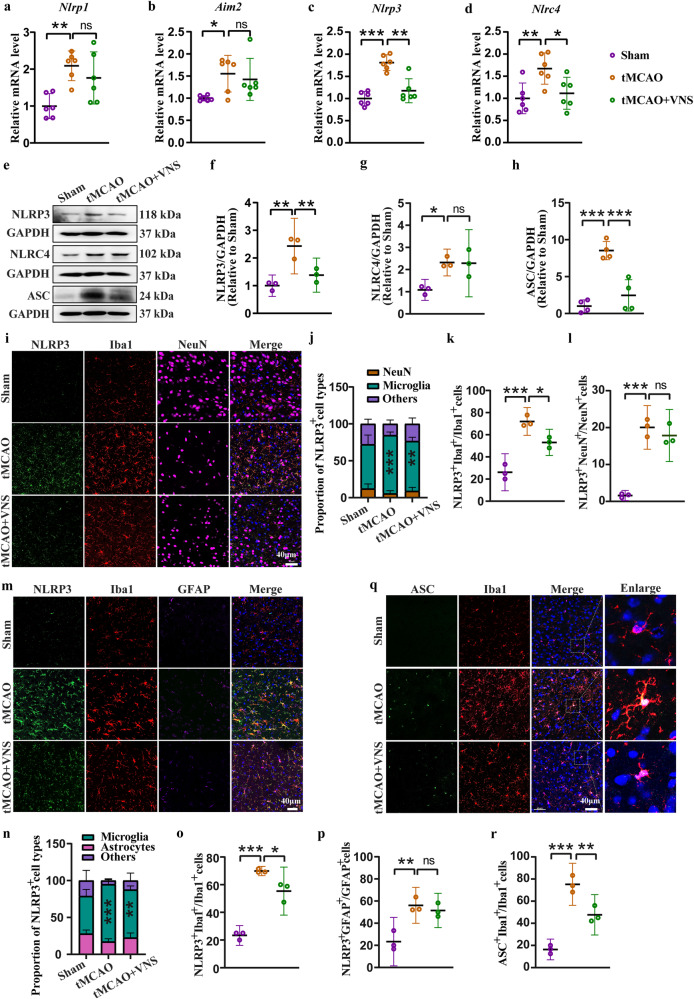

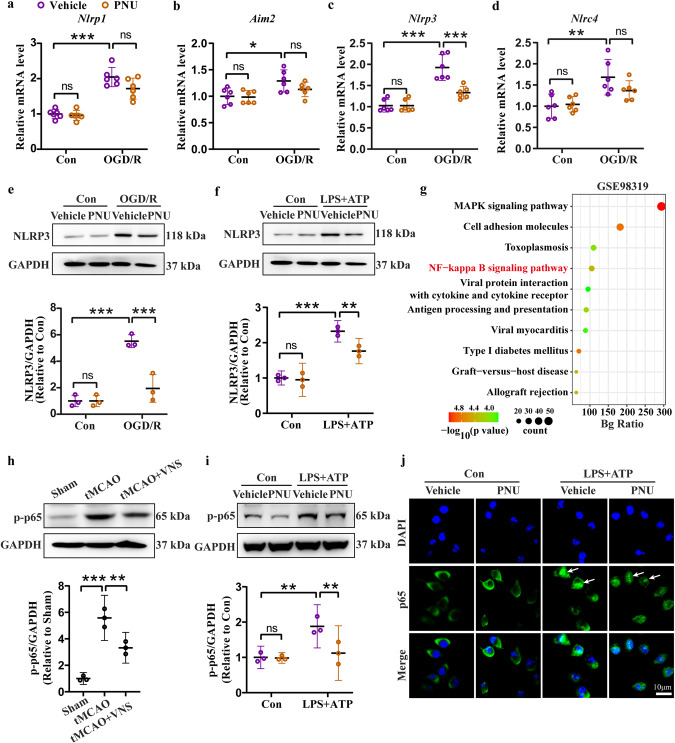

VNS treatment inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia

Inflammasomes, including NLRP1, AIM2, NLRP3, and NLRC4, are predominantly expressed in the brain and play a critical role in the regulation of neuroinflammation [21]. Our findings revealed a significant increase in the mRNA levels of Nlrp1, Aim2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 in the penumbra region of tMCAO mice. However, VNS treatment effectively inhibited the upregulation of Nlrp3 and Nlrc4 mRNA levels, while having no effect on Nlrp1 and Aim2 mRNA levels (Fig. 3a–d). Subsequently, we assessed the protein levels of NLRP3, NLRC4, and ASC, an adaptor protein of the inflammasome, to investigate the impact of VNS on inflammasome activation. VNS treatment resulted in a decrease in NLRP3 expression but did not affect NLRC4 expression in the tMCAO model. Additionally, VNS treatment led to a reduction in ASC level (Fig. 3e–h). Thus, VNS negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the tMCAO model. Further analysis revealed that the upregulation of NLRP3 was primarily observed in microglia, rather than neurons (Fig. 3i–l), or astrocytes (Fig. 3m–p), as confirmed by immunofluorescence staining of NLRP3, Iba1, NeuN, and GFAP. Notably, VNS treatment significantly decreased the number of NLRP3-positive microglia in the tMCAO model. Additionally, ASC levels were reduced in microglia following VNS treatment (Fig. 3q, r). Overall, our data suggest that the microglial NLRP3 inflammasome represents a therapeutic target of VNS for the treatment of ischemic stroke.

Fig. 3. VNS treatment inhibits microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the penumbra region of tMCAO mice.

a–d Effects of VNS treatment on mRNA levels of Nlrp1, Aim2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 in the penumbra area of tMCAO mice examined by RT-PCR, n = 6. e–h Representative blots quantitative analyses showing the effects of VNS treatment on the expression of NLRP3, NLRC4, and ASC in the penumbra area of tMCAO mice, n = 3–4. i–l Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of NLRP3 positive cells in neurons and microglia, n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Sham groups (NLRP3 positive microglia in j), scale bar: 40 μm. m–p Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of NLRP3 positive cells in microglia and astrocytes, n = 3, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Sham groups (NLRP3 positive microglia in n), scale bar: 40 μm. q, r Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of ASC positive microglia, n = 3, scale bar: 40 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns no significance.

VNS treatment preserves α7nAChR expression in the tMCAO model

Stimulation of the vagus nerve produces endogenous acetylcholine, which modulates pathophysiological processes, such as neurotransmission and inflammation, by binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChR) [22, 23]. nAChR is widely expressed in the central nervous system, regulating brain function, and brain-enriched subtypes of nAChR were examined in our study. By analyzing the GEO dataset (GSE98139), we identified that most of the nAChR coding genes were differentially expressed between Sham and tMCAO mice (Fig. 4a). Thereafter, we validated the mRNA levels of these nAChR coding genes. In the tMCAO model, decreased mRNA levels of Chrna5, Chrna6, Chrna7, Chrnb2, Chrnb3, and Chrnb4 were observed, while no alteration of the mRNA levels of Chrna2, Chrna3, and Chrna4. Intriguingly, VNS treatment upregulated the mRNA level of Chrna7 but not others (Fig. 4b-j). Consistently, we then found that VNS treatment reversed the decreased protein level of α7nAChR (Fig. 4k, l). These results suggest the essential role of α7nAChR for VNS treatment in the tMCAO model.

Fig. 4. VNS treatment preserves α7nAChR expression in the penumbra area of tMCAO mice.

a Heatmap showing the differentially expressed genes related to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors reanalyzed using GSE98319 dataset. b–j Effects of VNS treatment on the mRNA levels of Chrns in the penumbra area, n = 6. k, l Representative blots and quantification of α7nAChR showing the upregulation of α7nAChR by VNS treatment in the penumbra area of tMCAO mice, n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns no significance.

Blockade of α7nAChR negates the therapeutic efficacy of VNS in ischemic stroke

To validate the role of α7nAChR in VNS treatment for ischemic stroke, we employed methyllycaconitine citrate (MLA) as an antagonist to block α7nAChR. MLA was administered via intraperitoneal injection in mice. The administration of MLA effectively abolished the improvement in neurological function achieved by VNS treatment (Fig. 5a) and also mitigated the beneficial effects of VNS on ischemic infarction (Fig. 5b, c). Importantly, MLA treatment hindered the inhibitory effect of VNS on NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Fig. 5d–f). Immunofluorescence staining further demonstrated that the reduction in the number of NLRP3-positive microglia induced by VNS treatment was also nullified by MLA (Fig. 5g, h). Consequently, the blockade of α7nAChR by MLA resulted in the reversion of the inhibitory effects of VNS on Caspase1 and IL-1β maturation (Fig. 5i–k). Together, our results uncover that the protective effect of VNS against ischemic injury is dependent on α7nAChR.

Fig. 5. Pharmacological inhibition of α7nAChR abrogates the protective effect of VNS treatment on ischemic injury.

a mNSS score showing the blockade of VNS-improved neurological function in the MLA-treated mice subjected to tMCAO model, n = 6. b, c TTC staining and quantification showing the blockade of VNS-induced reduction in infarct volume in the MLA-treated mice subjected to tMCAO model. Scale bar: 1.0 cm, n = 6. d–f Representative blots and quantification of NLRP3 and ASC in the penumbra area, n = 3. g, h Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of NLRP3 positive microglia, n = 3, scale bar: 40 μm. i–k Representative blots and quantification of Caspase1 and IL-1β in the penumbra area, n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns no significance. Mice were administered MLA at 2.5 mg/kg intraperitoneally 1 h before tMCAO model.

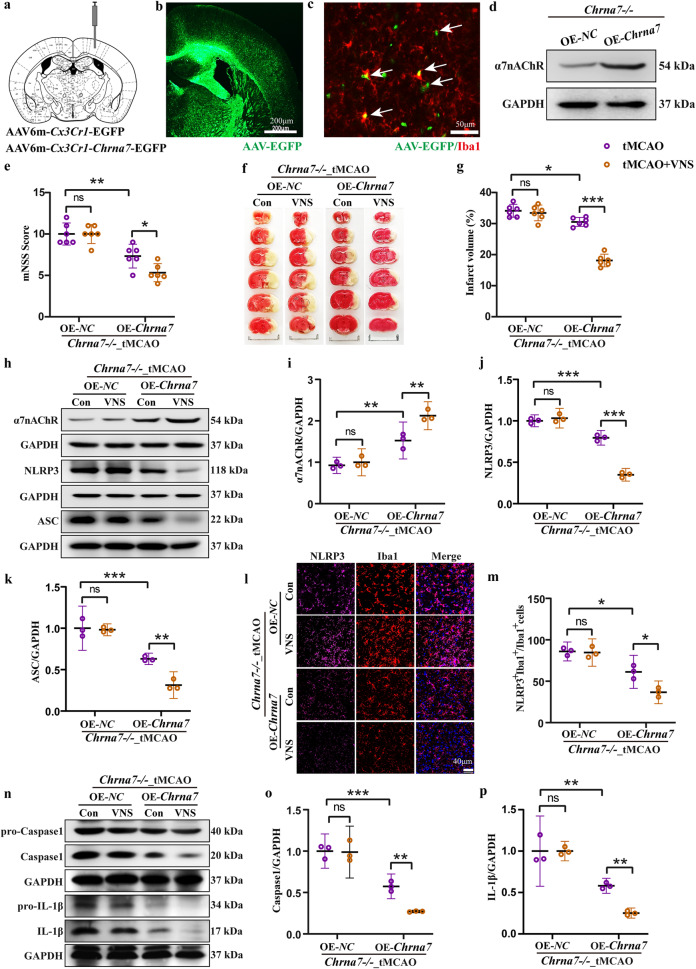

Microglial Chrna7 is required for VNS treatment in the tMCAO model

Chrna7 knockout (KO) mice were used to further validate the reliance of the protective effects of VNS against ischemic injury on α7nAChR (Fig. 6a–c). In comparison to wild-type (WT) mice, our data revealed that Chrna7 KO mice were more susceptible to tMCAO-induced injury, but were not sensitive to VNS treatment, including the blockade of the therapeutic effects on neurological function (Fig. 6d) and infarction (Fig. 6e, f). Consistent with the MLA treatment, enhanced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome was observed in the Chrna7 KO mice compared to WT mice, and VNS treatment failed to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the Chrna7 KO mice (Fig. 6g–i). Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of VNS treatment on NLRP3-positive microglia activation (Fig. 6j, k) as well as Caspase1 and IL-1β maturation (Fig. 6l–n) were completely abolished in Chrna7 KO mice. Collectively, these findings provide further confirmation that α7nAChR is indispensable for the therapeutic effects of VNS treatment in ischemic injury.

Fig. 6. Genetic deletion of Chrna7 abolishes the therapeutic effect of VNS treatment on ischemic injury.

a Genotyping of wide type (WT) and Chrna7 knockout (KO) mice, n = 6. b, c Undetectable mRNA level of Chrna7 in the brain of Chrna7 KO mice by qPCR, n = 6. d mNSS score showing the blockade of VNS-improved neurological function in the Chrna7 KO mice subjected to tMCAO model, n = 6. e, f TTC staining and quantification showing the blockade of VNS-induced reduction in infarct volume in the Chrna7 KO mice subjected to tMCAO model. Scale bar: 1.0 cm, n = 6. g–i Representative blots and quantification of NLRP3 and ASC in the penumbra area, n = 3. j, k Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of NLRP3 positive microglia, n = 3, scale bar: 40 μm. l–n Representative blots and quantification of Caspase1 and IL-1β in the penumbra area, n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns no significance.

To further investigate the importance of microglial α7nAChR in the therapeutic effects of VNS treatment, we conducted an experiment in which microglial Chrna7 was overexpressed in the Chrna7 KO mice (Fig. 7a–d). Interestingly, the overexpression of microglial Chrna7 resulted in a reduction of tMCAO-induced ischemic injury, as evidenced by improvements in neurological function and a decrease in infarct volume. Importantly, the therapeutic effects of VNS treatment were restored in the Chrna7 KO mice overexpressing microglial Chrna7 (Fig. 7e–g). Notably, the inhibitory effect of VNS treatment on NLRP3 inflammasome activation was also reinstated in the Chrna7 KO mice with microglial Chrna7 overexpression (Fig. 7h–k). Furthermore, we observed that the overexpression of microglial Chrna7 recovered the inhibition of NLRP3-positive microglia activation (Fig. 7l, m), as well as Caspase1 and IL-1β maturation (Fig. 7n–p), in Chrna7 KO mice treated with VNS. These findings provide compelling evidence that the therapeutic effects of VNS intervention in ischemic stroke are dependent on the activation of microglial α7nAChR.

Fig. 7. Overexpression of microglial Chrna7 reinstates the therapeutic efficacy of VNS intervention on ischemic injury.

a Illustration of the injection site of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAVs). b Representative immunofluorescence image showing the infection area of AAVs, scale bar: 200 μm. c Representative immunofluorescence image showing the infected microglia by AAVs, scale bar: 50 μm. d Representative blots showing the overexpression of α7nAChR in the brain of Chrna7 KO mice. e mNSS score showing the recovery of VNS treatment on neurological function by overexpression of microglial Chrna7 in the Chrna7 KO mice subjected to tMCAO model, n = 6. f, g TTC staining and quantification showing the retrieval of the effect of VNS treatment on reduction in infarct volume by overexpression of microglial Chrna7 in the Chrna7 KO mice subjected to tMCAO model. Scale bar: 1.0 cm, n = 6. h–k Representative blots and quantification of α7nAChR, NLRP3, and ASC in the penumbra area, n = 3. l, m Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of NLRP3 positive microglia, n = 3, scale bar: 40 μm. n–p Representative blots and quantification of Caspase1 and IL-1β in the penumbra area, n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns no significance.

α7nAChR activation suppresses NF-κB signaling-mediated priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome

We further explored the potential role of α7nAChR in NLRP3 inflammasome activation using PNU-282987 (PNU), an agonist of α7nAChR. The oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R) model was performed in BV2 cells to investigate the cascade of ischemic injury in vitro. Consistent with the results in vivo, Nlrp1, Aim2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 mRNA levels were significantly increased in the OGD/R model, while Nlrp3 mRNA level was reduced by PNU treatment (Fig. 8a–d). The change in NLRP3 protein level was validated by Western blotting, showing the same trend as mRNA level (Fig. 8e). To provide straightforward evidence, we performed the LPS + ATP model, which is a canonical model of NLRP3 inflammasome activation [24]. Importantly, LPS + ATP induced a significant upregulation of NLRP3 expression, which was diminished by PNU treatment (Fig. 8f). Therefore, we confirm that activation of α7nAChR impedes NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Fig. 8. Activation of α7nAChR by PNU treatment inhibits NLRP3 expression through NF-κB signaling.

a–d Effects of PNU-282987 (PNU) on mRNA levels of Nlrp1, Aim2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 in the OGD/R model, n = 6. e, f Representative blots and quantification of NLRP3 showing the inhibitory effect of PNU-282987 on NLRP3 expression in the OGD/R and LPS + ATP models, n = 3. g The NF-κB signaling is involved in the ischemic stroke injury analyzed using GSE98319 dataset by KEGG. h, i Representative blots and quantification showing the effects of VNS treatment and PNU treatment on the phosphorylation of p65, n = 3. j Representative immunofluorescence images of p65 showing the inhibitory effect of PNU on p65 nucleus translocation in the LPS + ATP model, scale bar: 10 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns: no significance. BV2 cells were pretreated with PNU-282987 (PNU) at 0.1 μM followed by OGD/R model or LPS (100 ng/mL, 5.5 h) + ATP (5 mM, 0.5 h) model.

We identified that NF-κB signaling was involved in the tMCAO-induced injury by analyzing the GEO dataset (GSE98319, Fig. 8g). The NF-κB signaling is required for priming the NLRP3 inflammasome [25]. Activation of NF-κB signaling is characterized by phosphorylation and nucleus translocation of p65. We found that the phosphorylation level of p65 (p-p65) was extensively increased in both tMCAO and LPS + ATP models, while VNS treatment in vivo (Fig. 8h) and PNU treatment in vitro (Fig. 8i) induced decrease in the level of p-p65. Immunofluorescence staining of p65 in BV2 cells displayed conspicuous nucleus translocation by LPS + ATP stimulation, but PNU treatment blocked this translocation (Fig. 8j). Thus, we presume that α7nAChR activation inhibits inflammatory responses through blunting NF-κB signaling-mediated priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

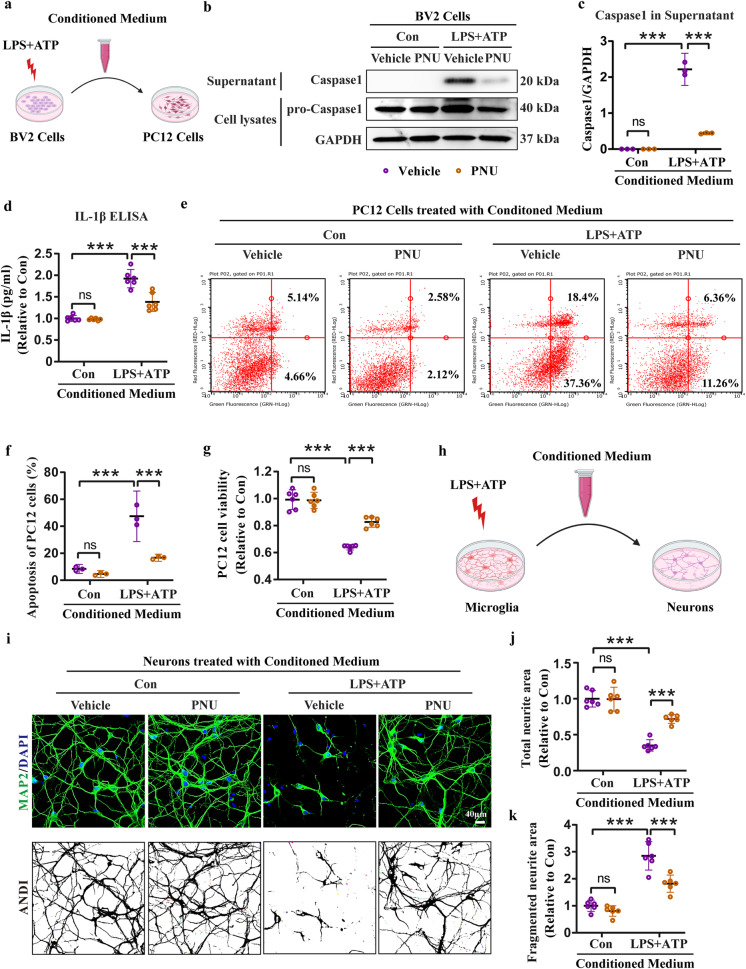

α7nAChR activation mitigates neurotoxic effects of microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation

To investigate PNU-induced inhibitory effect of microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation on neuronal survival, we collected conditioned medium from BV2 cells to culture PC12 cells (Fig. 9a). Within the conditioned medium containing LPS + ATP, we found a robust production of Caspase1 and IL-1β, indicating the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. However, the production of Caspase1 and IL-1β was reduced in the conditioned medium containing PNU (Fig. 9b–d). To assess the impact on neuronal survival, we cultured PC12 cells with the conditioned medium obtained from BV2 cells. Interestingly, the PNU-containing conditioned medium significantly ameliorated the apoptosis induced by the LPS + ATP-containing conditioned medium, as demonstrated by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 9e, f). Consistently, the conditioned medium containing PNU reversed the decreased cell viability induced by the conditioned medium containing LPS + ATP (Fig. 9g). Furthermore, we extended this workflow using primary microglia and neurons (Fig. 9h). Morphology analysis of neurons revealed that the conditioned medium collected from LPS + ATP-treated microglia led to a significant reduction in total neurites and an increase in fragmented neurites, indicating neuronal damage. In contrast, the conditioned medium containing PNU preserved the normal morphology of neurons, suggesting a protective effect (Fig. 9i–k). Overall, our results demonstrate that microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation is detrimental to neuronal survival, while activation of microglial α7nAChR is effective to rescue neuronal death.

Fig. 9. Activation of α7nAChR by PNU treatment inhibits microglial NLRP3 inflammasome-induced neuronal death.

a Workflow of conditioned medium collection from BV2 cells for PC12 cells culture. b, c Representative blots and quantification of Caspase1 in the conditioned medium collected from BV2 cells, n = 3. d ELISA assay showing the release of IL-1β in the conditioned medium collected from BV2 cells, n = 6. e, f Flow cytometry assay and quantification showing the protective effect of PNU-containing conditioned medium on apoptosis of PC12 cells, n = 3. g Increased viability of PC12 cells by PNU-containing conditioned medium treatment examined by CCK-8 assay, n = 6. h Workflow of conditioned medium collection from microglia for primary neurons culture. i–k Morphology analyses of neurons treated with conditioned medium using MAP2 staining and ImageJ (ANDI, automated neurite degeneration index), n = 6, scale bar: 40 μm. ***P < 0.001, ns no significance. BV2 cells and microglia were pretreated with PNU-282987 (PNU) at 0.1 μM followed by LPS (100 ng/mL, 5.5 h) + ATP (5 mM, 0.5 h) model, and then conditioned medium was collected. PC12 cells and neurons were cultured in the conditioned medium for 24 h followed by further experiments.

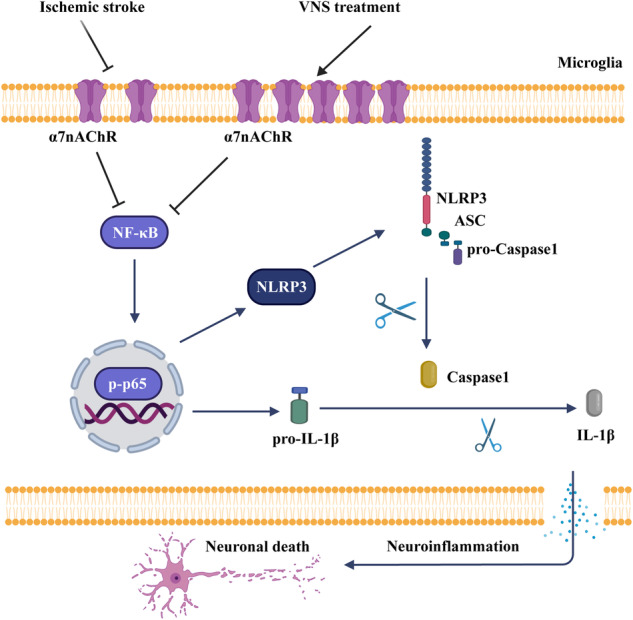

To conclude, our study reveals the potential and mechanism of VNS in ischemic stroke treatment. We propose that ischemic stroke activates microglia in the ischemic core and penumbra regions of the brain, followed by the NLRP3 inflammasome activation-induced neuroinflammation, which finally triggers neuronal death. VNS treatment rescues neurons mostly in the penumbra area through activation of microglial α7nAChR to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome activation and ensuing neuroinflammation (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Schematic illustration of α7nAChR-dependent inactivation of microglial NLRP3 inflammasome.

In stroke, activation of the NF-κB signaling upregulates the expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β, followed by assembly and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which promotes the maturation and release of IL-1β, resulting in neuroinflammation and neuronal death. However, VNS treatment activates microglial α7nAChR, which negatively regulates the NF-κB signaling, thereby inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome-induced neuroinflammation and neuronal death.

Discussion

Stroke is a significant cause of mortality and disability globally, and despite advancements in stroke therapy, there is still a need for the development of more effective treatments to enhance outcomes for stroke patients. One potential therapy that has gained attention in recent years is vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). VNS paired with rehabilitation has been proved to improve arm impairment of ischemic stroke patients [12], while effects of VNS on acute cerebral I/R injury and the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Our study demonstrates that VNS treatment, regardless of its timing, resulted in improved neurological function and reduced infarct volume in the tMCAO mouse model. Compared to the VNS treatment during and after ischemic stroke, pretreatment of VNS (Pre-VNS) was the most effective option. Mechanistically, we identified that microglial α7nAChR was the target of VNS to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome activation, thereby reducing neuroinflammation. Beyond addressing the knowledge gaps concerning the potential mechanism involved in VNS treatment of acute ischemic stroke, we aimed to provide new therapeutic strategy via manipulating microglial-mediated neuroinflammation for ischemic stroke.

Microglia are a type of immune cells resident in the central nervous system (CNS). During ischemic stroke, activated microglia migrate to the sites of injury and trigger neuroinflammation by releasing substantial pro-inflammatory cytokines [26]. In this study, we found that VNS treatment markedly reduced the recruitment and activation of microglia to the ischemic core and penumbra areas of the brain, leading to inactivation of microglial inflammasomes and attenuation of neuroinflammation. These results are consistent with previous findings demonstrating the inhibitory effect of VNS on neuroinflammation [27]. However, our study further clearly depicted the underlying mechanism of the anti-inflammatory effect of VNS. Inflammasomes, including NLRP1, AIM2, NLRP3, and NLRC4, are abundant in the CNS, and the NLRP3 inflammasome is considered the primary contributor to microglia-mediated neuroinflammation [28, 29]. In the tMCAO mouse model, we found that the mRNA and protein levels of NLRP3 and NLRC4 but not NLRP1 and AIM2 were increased remarkably, while VNS treatment significantly reduced the expression of NLRP3, rather than NLRC4, suggesting the crucial role of VNS in regulating activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Further, we observed this phenomenon mostly in microglia of the penumbra area. Therefore, our study deepens the understanding of the regulation of VNS on neuroinflammation.

Vagus nerve activated by VNS releases acetylcholine, which is a neurotransmitter that can bind to cholinergic receptors on immune cells [30]. In the present study, we distinguished the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in microglia in the context of ischemic stroke. We examined 9 subtypes of nAChR predominantly expressed in the brain, and found that α7nAChR as the primary subtype of nAChR responded to both ischemic injury and VNS treatment. To verify the role of α7nAChR in VNS treatment, selective inhibitor of α7nAChR, MLA, and Chrna7 knockout mice were used in the context of tMCAO mouse model. Consistently, we found that both pharmacological inhibition of α7nAChR and genetic deletion of Chrna7 blocked the neuroprotective effect of VNS on ischemic stroke. These data suggest the requirement of α7nAChR-dependent cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway for VNS treatment of ischemic stroke.

To elucidate the cell type-specific role of α7nAChR in VNS treatment, we conducted an experimental approach involving the overexpression of microglial Chrna7 in Chrna7 knockout mice. In the Chrna7 KO mice subjected to the tMCAO model, the inhibitory effect of VNS on microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation was found to be blocked. However, the reinstatement of NLRP3 inflammasome inactivation by VNS treatment was observed upon the overexpression of microglial Chrna7. These findings provide compelling evidence supporting the notion that microglial α7nAChR represents a promising therapeutic target for VNS treatment in ischemic stroke.

In the conducted mechanistic study, we utilized the α7nAChR agonist PNU in BV2 cells to mimic VNS treatment in an in vitro context. According to the findings, the administration of PNU resulted in an increased expression of α7nAChR [31], mirroring the effect observed in our study’s animal experiments with VNS-induced α7nAChR expression. Nevertheless, the precise mechanism responsible for the upregulation of microglial α7nAChR expression induced by both VNS and PNU remains elusive. The involvement of transcriptional or degradation mechanisms in the modulation of α7nAChR warrants further investigation in these circumstances. In the present study, treatment with PNU successfully inhibited the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in both the OGD/R model (an established in vitro model of ischemic stroke) and the LPS + ATP model (a well-known model of NLRP3 inflammasome activation). Additionally, PNU treatment attenuated NF-κB signaling, as indicated by the reduction in p65 phosphorylation and its translocation to the nucleus. Consequently, the inflammatory response in terms of neuroinflammation was mitigated, leading to a decrease in the release of Caspase 1 and IL-1β. To assess the anti-inflammatory effects of PNU on neuronal survival, we conducted experiments using conditioned medium in two scenarios: PC12 cells treated with conditioned medium collected from BV2 cells, and primary neurons treated with conditioned medium obtained from microglia. Remarkably, our findings consistently demonstrated the neuroprotective effects of PNU treatment, which were attributed to the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome-induced neuroinflammation. Overall, our data shed light on the underlying mechanism of VNS therapy for ischemic stroke, highlighting its anti-inflammatory effects, particularly in the suppression of NF-κB signaling-mediated microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

The involvement of α7nAChR has been documented in neuronal pyroptosis and the modulation of microglial phenotype during stroke [10, 32, 33]. However, the understanding of the role of α7nAChR in microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the context of stroke remains limited. In our current investigation, we employed a combination of genetic manipulations, including Chrna7 knockout mice and microglial Chrna7 overexpression mice, as well as pharmacological interventions using the α7nAChR inhibitor methyllycaconitine and agonist PNU-282987. Through these comprehensive approaches, our study provides valuable insights into the regulatory role of α7nAChR in microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation during ischemic stroke. Notably, our study focused on the pre-treatment of VNS, which holds potential as a safe and effective strategy for stroke prevention. Further experiments are warranted to elucidate the neuroprotective mechanisms associated with VNS treatment, particularly in post-treatment scenarios, which may differ from pre-treatment effects. Nonetheless, our findings contribute to the advancement of novel strategies for the prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke and offer new perspectives on the neuroprotective effects of VNS treatment.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82204357, 82173797), the National Key R&D Program of China (2021ZD0202903), the Natural Science Fund of the Basic Research Program of the Science and Technology Department of Jiangsu Province (BK20231267) and the Medical Research Project of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission (M2022071).

Author contributions

ML, XL, and LC conceived and designed this study. XMX, YD, YPW, SYJ, and YFD acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data. YZ, RXH, and CQ contributed to the methodologies. LC wrote the original manuscript draft. ML and XL revised the manuscript and supervised the project. All authors have confirmed the submission of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Xiao-mei Xia, Yu Duan, Yue-ping Wang

Contributor Information

Lei Cao, Email: leicao@njmu.edu.cn.

Xiao Lu, Email: luxiao1972@163.com.

Ming Lu, Email: lum@njmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Brainin M, Norrving B, Martins S, Sacco RL, Hacke W, et al. World Stroke Organization (WSO): global stroke fact sheet 2022. Int J Stroke. 2022;17:18–29. doi: 10.1177/17474930211065917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul S, Candelario-Jalil E. Emerging neuroprotective strategies for the treatment of ischemic stroke: an overview of clinical and preclinical studies. Exp Neurol. 2021;335:113518. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayaraj RL, Azimullah S, Beiram R, Jalal FY, Rosenberg GA. Neuroinflammation: friend and foe for ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflamm. 2019;16:142. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1516-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao S, Wu J, Liu R, Wang S, Luo J, Yang Y, et al. A novel compound DBZ ameliorates neuroinflammation in LPS-stimulated microglia and ischemic stroke rats: role of Akt(Ser473)/GSK3beta(Ser9)-mediated Nrf2 activation. Redox Biol. 2020;36:101644. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jia H, Qi X, Fu L, Wu H, Shang J, Qu M, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor ameliorates ischemic stroke by reprogramming the phenotype of microglia/macrophage in a murine model of distal middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neuropathology. 2022;42:181–9. doi: 10.1111/neup.12802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge Y, Wang L, Wang C, Chen J, Dai M, Yao S, et al. CX3CL1 inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome-induced microglial pyroptosis and improves neuronal function in mice with experimentally-induced ischemic stroke. Life Sci. 2022;300:120564. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo L, Liu M, Fan Y, Zhang J, Liu L, Li Y, et al. Intermittent theta-burst stimulation improves motor function by inhibiting neuronal pyroptosis and regulating microglial polarization via TLR4/NFkappaB/NLRP3 signaling pathway in cerebral ischemic mice. J Neuroinflamm. 2022;19:141. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02501-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sapkota A, Choi JW. Oleanolic acid provides neuroprotection against ischemic stroke through the inhibition of microglial activation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2022;30:55–63. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2021.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez HFJ, Yengo-Kahn A, Englot DJ. Vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2019;30:219–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang H, Li J, Zhou Q, Li S, Xie C, Niu L, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation alleviated cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury in rats by inhibiting pyroptosis via alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8:54. doi: 10.1038/s41420-022-00852-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Y, Li L, Tan X, Liu B, Zhang Y, Li C. miR-210 mediates vagus nerve stimulation-induced antioxidant stress and anti-apoptosis reactions following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. J Neurochem. 2015;134:173–81. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson J, Liu CY, Francisco GE, Cramer SC, Wolf SL, Dixit A, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation paired with rehabilitation for upper limb motor function after ischaemic stroke (VNS-REHAB): a randomised, blinded, pivotal, device trial. Lancet. 2021;397:1545–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00475-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Xu S, Zhang H, Qian K, Huang J, Gu X, et al. Stimulation of alpha7-nAChRs coordinates autophagy and apoptosis signaling in experimental knee osteoarthritis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:448. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03726-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaar KL, Brenneman MM, Savitz SI. Functional assessments in the rodent stroke model. Exp Transl Stroke Med. 2010;2:13. doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi M, Cao L, Cao X, Zhu M, Zhang X, Wu Z, et al. DR-region of Na+/K+ ATPase is a target to treat excitotoxicity and stroke. Cell Death Dis. 2018;10:6. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1230-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao L, Xiong S, Wu Z, Ding L, Zhou Y, Sun H, et al. Anti-Na+/K+-ATPase immunotherapy ameliorates alpha-synuclein pathology through activation of Na+/K+-ATPase alpha1-dependent autophagy. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabc5062. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc5062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clements RT, Fuller LE, Kraemer KR, Radomski SA, Hunter-Chang S, Hall WC, et al. Quantification of neurite degeneration with enhanced accuracy and efficiency in an in vitro model of Parkinson’s disease. eNeuro. 2022;9:ENEURO.0327–21.2022. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0327-21.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu M, Cao L, Xiong S, Sun H, Wu Z, Bian JS. Na+/K+-ATPase-dependent autophagy protects brain against ischemic injury. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:55. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Y, Reis C, Chen S. NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathophysiology of hemorrhagic stroke: a review. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2019;17:582–9. doi: 10.2174/1570159X17666181227170053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brahadeeswaran S, Sivagurunathan N, Calivarathan L. Inflammasome signaling in the aging brain and age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59:2288–304. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02683-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matta JA, Gu S, Davini WB, Bredt DS. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor redux: discovery of accessories opens therapeutic vistas. Science. 2021;373:eabg6539. doi: 10.1126/science.abg6539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paul SM, Yohn SE, Popiolek M, Miller AC, Felder CC. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor agonists as novel treatments for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179:611–27. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.21101083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theofani E, Semitekolou M, Samitas K, Mais A, Galani IE, Triantafyllia V, et al. TFEB signaling attenuates NLRP3-driven inflammatory responses in severe asthma. Allergy. 2022;77:2131–46. doi: 10.1111/all.15221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JP. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:477–89. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Leak RK, Cao G. Microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and neuroplasticity after stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022;16:980722. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.980722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huffman WJ, Subramaniyan S, Rodriguiz RM, Wetsel WC, Grill WM, Terrando N. Modulation of neuroinflammation and memory dysfunction using percutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in mice. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voet S, Srinivasan S, Lamkanfi M, van Loo G. Inflammasomes in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. EMBO Mol Med. 2019;11:e10248. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201810248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Ren W, Wu Q, Liu T, Wei Y, Ding J, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation: a therapeutic target for cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022;15:847440. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.847440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonaz B, Picq C, Sinniger V, Mayol JF, Clarencon D. Vagus nerve stimulation: from epilepsy to the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:208–21. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su Y, Zhang W, Zhang R, Yuan Q, Wu R, Liu X, et al. Activation of cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway ameliorates cerebral and cardiac dysfunction after intracerebral hemorrhage through autophagy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:870174. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.870174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao XP, Zhao Y, Qin XY, Wan LY, Fan XX. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury and promotes microglial M2 polarization via interleukin-17A inhibition. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;67:217–26. doi: 10.1007/s12031-018-1227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ekici F, Karson A, Dillioglugil MO, Gurol G, Kir HM, Ates N. The effects of vagal nerve stimulation in focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion model. Turk Neurosurg. 2013;23:451–7. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.7114-12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]