Abstract

To assess the effects of warm-up music and low dose (3 mg·kg−1) of caffeine (CAF) on female taekwondo athlete’s activity profile and psychophysiological responses during simulated combat. In a double-blinded, randomized, crossover study, 16 female athletes participated in simulated combats under one control and 5 experimental conditions [i.e., CAF alone (CAF), placebo alone (PL), CAF with music (CAF + M), PL with music (PL + M), and no supplement with music (M)]. After warming-up, athletes rated their felt arousal (FAS). Mean (HRmean) and peak (HRpeak) heart rate values were determined for each combat. After fighting, athletes rated their perceived exertion (RPE), feeling scale (FS), FAS, and physical enjoyment (PACES). Time-motion and technical-tactical variables were analyzed. CAF + M induced shorter skip and pause time, while attack time increased compared to other conditions (p < 0.05). Moreover, CAF + M increased single attacks, combined attacks, counter-attacks (p < 0.001), and defensive actions (p < 0.05) than other conditions. HRmean and HRpeak were lower under CAF + M than other conditions (p < 0.05). Additionally, higher FAS post-combat, FS, and PACES were observed under CAF + M, while RPE was lower (except CAF condition) compared to the other conditions (p < 0.05.Using CAF with warm-up music may increase combat cadence and improve the psychological state in female athletes more effectively than either strategy alone.

Keywords: Ergogenic aids, Activity profile, Attack, Performance

Subject terms: Physiology, Psychology

Introduction

In combat sports, such as taekwondo, competitions are organized according to weight categories, competition level, and sex1. During taekwondo combat, two opponents from the same category fight across three 2-min rounds (1 min rest in-between) with the objective of overcoming an opponent by obtaining a greater quantity of points for the execution of techniques to permitted scoring areas or by achieving a technical knockout2. Success within the sport may be determined by athletes’ technical, tactical, psychological, physical, and physiological characteristics1. The chances of winning an elite championship competition are marginal and require athletes to be able to effectively manage the anticipatory stress-response, changeable physiological responses, and potential fatigue that may arise from both single and repeated combat exposures3,4.

In the quest for optimal performance, athletes and coaches have a range of potential pre-conditioning and nutritional strategies at their disposal, many of which can be employed to facilitate performance on the day of competition5,6. In the context of the latter, nutritional ergogenic aids, such as caffeine (CAF), have the potential to acutely facilitate performance in a variety of settings and hence they are widely consumed by athletes6,7. Performance improvements following ingestion of CAF may be manifested through a variety of potential mechanisms, including binding to adenosine receptor sites, concomitant release of neurotransmitters, altered RPE and pain perception, enhanced muscle contractile properties, and improved intramuscular metabolic environment8,9.

Despite compelling evidence to support the efficacy of CAF in a variety of sport settings in males, research investigating the efficacy of CAF in females is in its relative infancy. Caution should remain in considering males and females as a homogenous group due to the observed differences in physiology and hormones that could potentially influence processes of absorption and metabolism6,10. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest differences in the ergogenic effect of CAF on performance across different sports11 and the occurrence of negative psychological disposition12 between males and females, albeit this has not been observed consistently13,14. Although the precise process causing the various reactions to the supplement is not yet understood, body composition and size may be among the influencing factors12. Specifically, CAF is mainly distributed through free body mass15, The larger percentage of adipose tissue may lead to higher CAF concentrations in the tissue and plasma12. Since female athletes tend to demonstrate greater body fat than their male counterparts1, this will also influence CAF absorption, plasma concentrations, and the occurrence of side effects16. Additionally, steroid hormone levels’ variation in females could influence the reactions brought on by CAF17. Actually, changes in hormone levels throughout the menstrual cycle affect the rate at which CAF is metabolized as well as the neuromuscular system function17. Concerted efforts have recently been made to address such deficiencies, and evidence is indeed emerging to support CAF’s ergogenic potential in female athletes in various sports settings6,18,19. Recent research in taekwondo has identified performance improvements on specific taekwondo tests following ingestion of 3 mg·kg−1 body mass of CAF in male or mixed samples of athletes20, albeit the translation of these findings to actual performance in combat is debatable. A limited number of studies have investigated the influence of CAF on performance in simulated combat using males or with unreported genders, with conflicting findings in terms of efficacy21,22. Further research investigating the influence of CAF on the activity profiles and psychophysiological responses to combat using female athletes is warranted.

Recent investigations using males23 or a mixed sample of taekwondo athletes20 have reported that combining CAF with other ergogenic aids or other warm-up strategies can result in additive effects on performance beyond that seen when using either strategy in isolation. Since it serves as a psychological ergogenic aid, music has been reported to improve affective balance, behavior, and cognitive skills associated with physical performance enhancement24,25. Interestingly, applying musical stimulus prior to exercise has received significant interest in the field of music research26. This is largely a function of the restrictions imposed on the use of audio devices during competition in different sports, and more specifically in taekwondo contests27. In this regard, warm-up music can be effective in delaying fatigue, and improving affective state associated with physical performance enhancement, especially, when the stimulus is self-selected26. However, such findings cannot be generalized between sexes, since the responsiveness to warm-up music intervention is often greater within male compared with female athletes27,28.

Despite the endocrinological differences between the sexes and the growing interest in menstrual cycle-specific research, exercise science and nutrition research continue to generalize results between males and females29. Given the significant differences in biology and behavior between genders, such inferences are not acceptable30. Whilst CAF18 and warm-up music26 benefits on female athletes have received only limited research attention, their synergistic effects have not been studied. Therefore, the present study investigated the acute effects of low dose of CAF and preferred warm-up music on the subsequent female taekwondo athletes’ responses during simulated combats. It has been documented that CAF acts as an adenosine antagonist by blocking its A1 and A2a receptors leading to improved neurotransmission, muscular excitation–contraction coupling, and sympathetic nervous system’ s activation while reducing pain perception9,31,32. Differently, improvements in performance following music listening are mediated through improved mood, exercise enjoyment, motivation and increased feelings of power, while reduced fatigue symptoms24,27. Since success in taekwondo competition is multifactorial and may be determined by the collective interplay between psychological responses, physical abilities and technical-tactical skills1, it was hypothesized that combining CAF and warm-up music may increase females athletes activity profiles and elicit more desirable psycho-physiological responses when compared with using either strategy in isolation.

Material and methods

Participants

Female athletes were recruited following a convenience sampling, as long as they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) classified as an active elite female athlete; (b) do not suffer from any restrictions to sports practice or hearing loss; (c) minimum age of 17 years with at least 7 years of taekwondo experience; (d) were not currently taking any form of contraceptives as its use may interferes with CAF metabolism and excretion14, and (e) have a regular menstrual cycle, defined as a variation lower than 3 days in the range of their menstrual cycles' length14 for the previous 2 months. The sample size required was priori estimated using the G*Power software (Version 3.1.9.4, University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany). The repeated measures ANOVA, within factors test, with six conditions revealed that a total sample size of 14 would be sufficient to find medium significant effects of condition (effect size f = 0.30, α = 0.05) with an actual power of 83%. Taking into consideration the risk of athlete dropout, 16 female elite black belt taekwondo athletes (age: 17 to 19 years; body mass: 43 to 59 kg; height: 152 to187 cm) were eligible and volunteered to participate in the present study. Athletes were distributed into < 49 kg (8 athletes), < 57 kg (6 athletes) and < 67kg (2 athletes) weight categories. They were training regularly 5 sessions per week, with each session lasting 2 h. According to the questionnaire of Bühler et al.33, the mean habitual CAF consumption ranged from 0.5 to 2.1 mg.kg−1 of body mass, indicating that athletes were low CAF consumers. Athletes reported an average menstrual cycle duration of 28 ± 1 day. The recruited athletes had no more than two days difference in-between even in the follicular (8 athletes) or luteal phase (8 athletes). The participants were asked to follow the same diet, avoid alcoholic substances and vigorous exercise, and restrain from CAF consumption (in drinks and supplements) 48 h before each experimental session. All participants and their parents were informed about the procedures, the possible risks and side effects involved in the investigation and they signed a written informed consent form. This study was conducted in accordance with the last Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was fully approved by the Committee of protection of southern persons (CPP SUD N◦ 0332/2021) before commencing experimentation.

Experimental design

Before commencing experimentation, athletes were familiarized with the testing procedures and questionnaires, and each athlete was instructed to select their most preferred music (i.e., music with tempo > 120 bpm) and indicate its motivational quotient using the Brunel Music Rating Inventory-234. In the testing sessions, athletes performed simulated combats using a double-blind, counterbalanced, crossover study design. Specifically, athletes ingested 3 mg.kg−1 of CAF or placebo (PL) (i.e., 3 mg.kg−1 of placebo comprising all-purpose bleached flour), in a double blind fashion. Allocation and assignment for each participant was performed by an independent, blinded staff member of our research team. During supplementation, participants were instructed to not discuss exchange or compare tastes and the investigators of the studied athletes supervised consumption compliance. Each trial was given an alphanumeric code in order to keep participants and researchers unaware of the supplement being tested in each experiment. This code was disclosed following the variables' analysis35. Following the supplements consumption, verbal questioning demonstrated that almost all of the participants were unable to differentiate between the supplements, proving the efficacy of blinding. After supplementation, athletes remained seated for 50 min and then executed an 8-min warm-up (i.e., included 4 min of low-intensity running and 4 min of technical drills) either with or without listening to their preferred music. The priori selected music was intensive with tempos ranging from 124 to 168 bpm. For each athlete, one preferred music was used for all music conditions and music volume was fixed at 80 dB for all participants28. The music track was looped in cased it ended before the warm-up was completed. In the no music conditions, headphones were worn but no music was played. A two-min rest period was given after the warm–up and the combats were subsequently conducted. Consequently, the fights were performed under five experimental and a control condition including: (a) no supplement without music (control); (b) CAF without music (CAF); (c) PL without music (PL); (d) CAF with music (CAF + M); (e) PL with music (PL + M) and (f) no supplement with music (M). Athletes were asked to rate their perceived activation after warming-up and immediately after fighting using the felt arousal scale (FAS), while feeling scale (FS), physical activity enjoyment (PACES) and the rating of perceived exertion (RPE) were determined after the combats. During each fight, mean and peak heart rate (HRmean and HRpeak) were determined. For each testing session, participants had their pre-competition meal (three hours before the onset of the trial) and 500 ml of water (two hours before the onset of the trial). To provide enough recovery time between interventions and ensure CAF removal, 7-day of washout period between the sessions were guaranteed36. All the sessions were scheduled in the evening hours (17:00–18:00 p.m) within their regular training timing sessions (i.e., 17:00–19:00 p.m).

Testing procedures

Simulated combats

The simulated combats were performed in accordance with official rules of World Taekwondo following the Olympic weight categories2. The combats consisted of three 2-min rounds interspersed with 1-min rest interval in which athletes wore their official protective equipment. A black belt taekwondo coach who was blinded to the supplement and the musical intervention that the athletes had received refereed the matches. All combats involved partners from the same condition (e.g., CAF vs. CAF)21. Block randomization method was used using an excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel 2007, Redmond, WA, USA) to arrange the combats and ensure a balance in sample size. All combats were recorded for subsequent analysis using 2 cameras (Canon 650D 18 Megapixels, ISO: 400, shutter speed: 1/125 s, f/4; Canon, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) placed at 1.5 m from the combat area.

Videos-analysis

The technical-tactical analysis included the determination of single attacks, combined attacks, counterattacks, and defensives actions. The time-motion variables included the attacks time, skip time and pause time. The recorded video footage was analyzed frame-by-frame using the Kinovea software (V 0.9.5, http://www.kinovea.org/). Two investigators who were highly experienced and familiar with taekwondo matches analyzed the combats and repeated the process one week later. Consensus was used to resolve disagreements between the two researchers. The values of Cohen’s kappa coefficient for inter-observer agreement and intraclass correlation coefficient for intra-observer agreement were higher than 0.9 indicating a high reliability of the video-analysis system.

Heart rate measurements

Heart rate (HR) was measured every 5 s throughout the taekwondo combats (Polar Team2 Pro System, Polar Electro OY, Kempele, Finland) and mean (HRmean) and peak (HRpeak) values were used for the analysis.

Rating of perceived exertion

Perceived exertion was assessed using the CR-10 Borg scale37. This is a scale ranging from “0” to “10”, with corresponding verbal expressions, gradually increase with the perceived sensation’s intensity (0 = nothing at all; 1 = Very week; 2 = week; 3–4 = Moderate; 5–6 = strong; 7–9 = very strong; and 10 = extremely strong). The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in the present study was 0.75.

The physical activity enjoyment scale (PACES)

The18 items original scale version was used to detect the level of pleasure and enjoyment of participants38. Items involved 11 negative and 7 positive items measured through a 7-point score ranging from 1 to 738 with the score (i.e., the sum of total responses for each athlete) range from 18 to 126. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in the present study was 0.79.

Feeling scale (FS)

The FS utilizes a single-item 11-point bipolar rating scale ranging from − 5 to + 5, with the stem ‘‘How do you currently feel?’’. Anchors are given at 0 (Neutral) and all odd integers, ranging from ‘‘Very Bad’’ at − 5 to ‘‘Very Good’’ at + 539. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.84 for the present study.

Felt arousal scale (FAS)

The FAS was used to measure arousal along a 6 points scale ranging from low arousal (1 point) to high arousal (6 points)40. The participants were instructed to mark the scale on the basis of their perceived activation after warming-up and fighting. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.72 for the present study.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 statistical software (IBM corps., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were presented as mean and standard deviation, and Median and Interquartile range values were reported for non-normal distribution data. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check and confirm the normality of data sets, and the Levene test was used to verify the homogeneity of variances. Sphericity was tested using the Mauchly test. For variables with normal distribution, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (condition) with repeated measurements was used, with Bonferroni adjustment for post hoc comparisons. Standardized effect size analysis (Cohen’s d) was used to interpret the magnitude of differences between variables and considered as: trivial (≤ 0.20); small (≤ 0.60); moderate (≤ 1.20); large (≤ 2.0); very large (≤ 4.0) (very large); and extremely large (> 4.0)41. The non-parametric Friedman test was used with the Wilcoxon signed rank test as post hoc for those variables that were not normally distributed. The rank biserial correlation coefficient (r) was calculated using the Wilcoxon Z-scores and the total number of observations (N) (i.e., r = Z/√N) and considered as 0.1 to < 0.3 (small), 0.3 to < 0.5 (moderate) and ≥ 0.5 (large) 42 The level of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Time-motion variables

For attack time, there was a main effect of condition (Chi2 = 70; df = 5; N = 16; p < 0.001), with CAF + M resulting in longer time than the other conditions (all, Z = − 3.52; r = 0.88; p < 0.001). Similarly, for skipping time, there was a main effect of condition (F5,11 = 245.50; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.99), with CAF + M eliciting shorter skipping time than the other conditions (all p < 0.001). Additionally, there was a main effect of condition for pause time (Chi2 = 36.61; df = 5; N = 16; p < 0.001), with CAF + M resulting in shorter time than control (Z = − 3.37; r = 0.84; p = 0.001), as well as M, CAF, PL and M + PL (all, Z = − 3.52; r = 0.88; p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Time-motion variables during simulated combat following different conditions (N = 16).

| Control | M | CAF | PL | PL + M | CAF + M | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | |

| Attack time (s) | – | 74.62/12.38 | – | 90.25/8.58a,d | – | 91.77/2.63 a,d | – | 73.71/9.82 | – | 91/6.13a,d | – | 125.78/4.63a,b,c,d,e |

| Skip time (s) | 235.41 (8.80) | – | 218.79 (7.99)a,d | – | 219.74 (5.75)ad | – | 235.01 (6.92) | – | 221.48 (5.56)ad | – | 193.42 (5.11)a,b,c,d,e | – |

| Pause time (s) | – | 51.17/11.78 | – | 50.48/8.49 | – | 47.98/6.40*,$,ɸ | – | 50.67/3.92 | – | 47.22/4.38$,ɸ | – | 40.50/4.57*,b,c,d,e |

adifferent from control at p < 0.001; bdifferent from M at p < 0.001; cdifferent from CAF at p < 0.001; ddifferent from PL at p < 0.001; edifferent from PL + M at p < 0.001; *different from control at p < 0.05; $different from M at p < 0.05; ɸdifferent from PL at p < 0.05; M: music; CAF: caffeine; PL: placebo; PL + M: placebo and music; CAF + M: caffeine and music; SD: standard deviation; Med/IQR: median/interquartile range; s: second.

Technical-tactical aspects

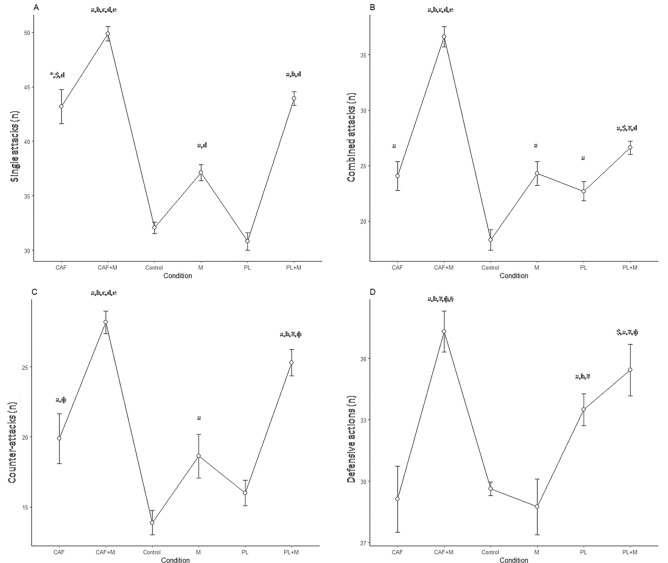

There was a main effect of condition for single attacks (Chi2 = 75.78; df = 5; N = 16; p < 0.001), with CAF + M resulting in higher attacks than control, PL and CAF (Z = − 3.53; r = 0.88; p < 0.001), as well as M and PL + M (Z = − 3.54; r = 0.89; p < 0.001). In addition, for combined attacks, there was a main effect of condition (F5,11 = 337; p < 0.001;ηp2 = 0.99), with CAF + M eliciting higher attacks than the other conditions (all, p < 0.001). Furthermore, for counter-attacks, there was a main effect of condition (F5,11 = 85.88; p < 0.001;ηp2 = 0.98), with CAF + M eliciting higher number of counter-attacks than the other conditions (all p < 0.001). Finally, there was a main effect of condition for defensive actions (Chi2 = 62.87; df = 5; N = 16; p < 0.001), with CAF + M resulting in higher actions than control, M (both, Z = -3.53; r = 0.88; p < 0.001), CAF (Z = − 3.42; r = 0.86; p = 0.001), PL (Z = − 3.40; r = 0.85; p = 0.001), and PL + M (Z = − 2.68; r = 0.67; p = 0.007) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Technical-tactical performance during simulated combat under different conditions (N = 16). Values are presented as mean (circle) and confidence interval (vertical line) with line plot; (A) single attacks; (B) combined attacks; (C) counter-attacks; (D) defensive actions; a: different from control at p < 0.001; b: different from M at p < 0.001; c: different from CAF at p < 0.001; d: different from PL at p < 0.001; e: different from PL + M at p < 0.001; *: different from control at p < 0.05; $: different from M at p < 0.05; ɸ: different from PL at p < 0.05; ¥: different from CAF at p < 0.05; §: different from PL + M at p < 0.05; M: music; CAF: caffeine; PL: placebo; PL + M: placebo and music; CAF + M: caffeine and music; n: number.

Heart rate responses

For HRmean, there was a main effect of condition (F5,11 = 29.31; p < 0.001;ηp2 = 0.93), with CAF + M eliciting lower values compared with the other conditions (all p < 0.001). Similarly, there was a main effect of condition for HRpeak (Chi2 = 48.62; df = 5; N = 16; p < 0.001), with CAF + M eliciting lower values than control (Z = − 3.36; r = 0.84; p = 0.001), M (Z = − 3.21; r = 0.80; p = 0.001), CAF (Z = − 3.44; r = 0.86; p = 0.001), PL (Z = − 3.53; r = 0.88; p < 0.001), and PL + M (Z = − 3.52; r = 0.88; p < p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceived exertion and heart rate responses in simulated combat following different conditions (N = 16).

| Control | M | CAF | PL | PL + M | CAF + M | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | |

| HR peak (beats/min) | – | 198/2¥ | – | 197/2.75¥,* | – | 201/2.5 | – | 196.5/2.5¥ | – | 196.5/3.25¥ | 187.5/5.75*,¥,$,d,e | |

| HR mean (beats/min) | 156.81 (2.76) | – | 155.38 (3.88)¥ | – | 158.88 (4.81) | – | 157.38 (1.50) | – | 155.19 (2.83) | – | 148.56 (2.73)a,b,c,d,e | – |

| RPE (a.u) | – | 9/1.5 | – | 9/0.75 | – | 8/1*,$,ɸ,§ | – | 9/0.75 | – | 9/0.75 | – | 8/1*,$,ɸ,§ |

adifferent from control at p < 0.001; bdifferent from M at p < 0.001; cdifferent from CAF at p < 0.001; ddifferent from PL at p < 0.001; edifferent from PL + M at p < 0.001; *different from control at p < 0.05; $different from M at p < 0.05; ɸdifferent from PL at p < 0.05; ¥different from CAF at p < 0.05; §different from PL + M at p < 0.05; M: music; CAF: caffeine; PL: placebo; PL + M: placebo and music; CAF + M: caffeine and music; SD: standard deviation; Med/IQR: median/interquartile range; HRpeak: heart rate peak; HRmean: heart rate mean; batt/min: battements per minute; RPE: perceived exertion; a.u: arbitrary unit.

Perceived exertion

There was a main effect of condition (Chi2 = 23.40; df = 5; N = 16; p < 0.001), with CAF + M eliciting lower values than control (Z = − 2.51; r = 0.63; p = 0.012), M (Z = − 2.84; r = 0.71; p = 0.005), PL (Z = − 2.68; r = 0.67; p = 0.007), and PL + M (Z = -3.07; r = 0.77; p = 0.002) (Table 2).

Feeling scale

There was a main effect of condition (Chi2 = 48.22; df = 5; N = 16; p < 0.001), with CAF + M eliciting higher values than control (Z = − 3.53; r = 0.88; p < 0.001), M (Z = − 3.33; r = 0.83; p = 0.001), CAF (Z = − 3.57; r = 0.89; p < 0.001), PL (Z = − 3.53; r = 0.88; p = 0.001) and PL + M (Z = − 3.48; r = 0.87; p = 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Female athletes’ psychological responses to each condition (N = 16).

| Control | M | CAF | PL | PL + M | CAF + M | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | Mean (SD) | Med/IQR | |

| FAS post warm-up | – | 1.5/1 | – | 3/1*¥ɸ§ | – | 2/1 | – | 2/1 | – | 1.5/1 | – | 2/1*ɸ§ |

| FAS post combat | – | 2/1 | – | 2.5/1*ɸ | – | 3/2*ɸ | – | 2/1.75 | – | 3/1*ɸ | – | 5/1.75a$¥d§ |

| FS | – | 0/2 | – | 1.5/1*ɸ | – | 1/0.75* | – | 0/1 | – | 1/0.75* | – | 4/1.75a$cɸ§ |

| PACES | 62.63 (4.40)d | – | 59.94 (4.25)d | – | 63.56 (4.32)d | – | 53.44 (2.28) | – | 58.75 (5.45)ɸ | – | 69.19 (3.37)*,b,c,d,e | – |

adifferent from control at p < 0.001; bdifferent from M at p < 0.001; cdifferent from CAF at p < 0.001; ddifferent from PL at p < 0.001; edifferent from PL + M at p < 0.001; *different from control at p < 0.05; $different from M at p < 0.05; ɸdifferent from PL at p < 0.05; ¥different from CAF at p < 0.05; §different from PL + M at p < 0.05; M: music; CAF: caffeine; PL: placebo; PL + M: placebo and music; CAF + M: caffeine and music; SD: standard deviation; Med/IQR: median/interquartile range; FAS: felt arousal scale; FS: feeling scale; PACES: physical activity enjoyment scale.

Felt arousal after warm-up

There was a main effect of condition (Chi2 = 19.27; df = 5; N = 16; p = 0.002), with CAF + M eliciting higher values than control (Z = -2.30; r = 0.58; p = 0.022), PL (Z = − 2.07; r = 0.52; p = 0.039), and PL + M (Z = − 2.14; r = 0.54; p = 0.033) (Table 3).

Felt arousal post_combat

There was a main effect of condition (Chi2 = 46.86; df = 5; N = 16; p < 0.001), with CAF + M eliciting higher values than control (Z = − 3.55; r = 0.89; p < 0.001), M (Z = − 3.40; r = 0.85; p = 0.001), CAF (Z = − 3.25; r = 0.81; p = 0.001), PL (Z = − 3.55; r = 0.89; p < 0.001), and PL + M (Z = − 3.32; r = 0.83; p = 0.001) (Table 3).

Physical enjoyment

There was a main effect of condition (F5,11 = 42.65; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.95), with CAF + M eliciting higher values compared with control (p = 0.001) and the other conditions (all p < 0.01(Table 3).

Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the effects of warm-up music and low dose CAF intake on female athletes’ performances during simulated taekwondo combat. As there are limited available data on the effects of these ergogenic aids in competitive events, especially within female athletes, this study is the first to address the synergetic effects of warm-up music and low dose of CAF on technical-tactical skills, time-motion variables and psycho-physiological responses during simulated combats. The overarching findings of the study suggest that combining a low dose of CAF with warm-up music could be a more effective strategy to increase combat cadence and generate more desirable psychological state in female athletes when compared with using either strategy alone.

The increase in the number of offensive and defensive actions performed under CAF + M condition suggest an increase in the intensity of combats through promoting more dynamic competition routine. It was previously reported that a moderate dose of CAF (i.e., 5 mg·kg−1) improved the total number of attacks performed in the second combat by 37.39% in male taekwondo athletes21. However, female athletes’ responses to warm-up music and CAF interventions during a competitive event were not investigated, meaning that it is difficult to form definitive comparisons between the studies. It is important to realize that maximal performance is associated with the execution of repeated high-intensity techniques during the entire match43. The ability to maintain intensive actions requires the development of specific physical attributes which rely heavily on both anaerobic and aerobic metabolism1. Using a similar CAF dose (i.e., 3 mg·kg−1), but a mixed sample of athletes, Ouergui et al.20 reported that CAF ingestion elicited a higher number of kicks recorded during the frequency speed of kick test (FSKT) using both simple (i.e., 10 s) and multiple (i.e. 5 × 10 s) versions. Both versions replicate some important characteristics/actions typically observed during the match44. This finding was confirmed in a later study comparing CAF effects in relation to competitive level and sex45, where female elite athletes also benefited from low dose CAF intake during the aforementioned tests. Ouergui et al.28 also reported that taekwondo athletes benefit from listening to music, as they were able to perform a higher number of techniques’ on such tests, particularly when listening to preferred music. For the first time, the present study shows that the combined use of warm-up music and low dose CAF ingestion may have additive effects on female athletes performance in simulated combat, a setting which is arguably a more ecologically valid.

During a typical contest, combat sports’ athletes use a variety of offensive and defensive actions to overcome the opponent46. Opponent behavior can influence athletes’ technical-tactical skills46. For instance, delivering a higher number of offensive actions often forces the opponent to counterattack, and vice versa, which may increase the overall intensity of the fight3. In the present study, the combined intervention (i.e., CAF + M) resulted in the execution of a greater number of counterattacks and defensive actions compared with the other conditions. During official taekwondo combats, time-motion analysis revealed that winners tended to display higher anaerobic power and execute a higher number of techniques when compared with their defeated counterparts47. Interestingly, female winners were reported to deliver more techniques during the combat when compared with their successful male counterparts48, which may highlight the effectiveness of this combination in increasing female athletes’ chance to win a competition.

Amongst the antagonist actions of CAF on adenosine is the activation of the sympathetic nervous system49. However, CAF effect on cardiac outputs appears to be dose18 and exercise intensity dependent (i.e., decline as exercise intensity increases)49. In the context of music, music preference correlates positively with relaxation50, with recent evidence51 reporting that upbeat music produced feelings of relaxation in male athletes. In the present study, preceding warm-up music by supplementation with low dose of CAF resulted in lower peak and mean heart rate values. While no neurological or hormonal measurements were conducted to explain mechanisms behind this response, maintaining lower HR values may reflect quicker recovery rate during the low-intensity actions due to improved parasympathetic recovery52 and a reduction in the central fatigue rate53. This postulation may be indirectly supported by time-motion results, since combining CAF and warm-up music reduced the skipping time. The increased combat cadence may reflect an improved ability to accelerate and achieve the opponent in a short distance and time54. This is not surprising since increases in vigor and reaction time’ are common CAF55 and warm-up music56 actions. Additionally, a decrease in fatigue perception could be among the reasons to maintain high-intensity actions31, which may influence the combat rhythm. Based on the fact that RPE score correlates with HR values during taekwondo contest57, it is not surprising that RPE and HR values simultaneously were lower under CAF + M condition. A decrease in RPE may reflect the ability of mitigating afferent nerves’ feedback, reducing the acute physiological responses58.

It has been reported that the ergogenic potential of CAF on taekwondo specific performance is dependent on competition level, with greater benefits in elite than sub-elite athletes45. For warm-up music, recent meta-analysis revealed that this stimulus present greater effects in highly trained subjects than less trained ones regarding psychological responses and the reverse for physical performances26. Since participants in the present study are elite athletes, their greater responses to the CAF + M condition may be related to complementary actions by CAF and music at the central and peripheral levels23. Specifically, CAF low doses (i.e., ≤ 3 mg.kg−1) act mainly on the central nervous system by increasing the prefrontal cortex activity and enhancing executive function59. For warm-up music, stimulus increased brain activity, which improved decision-making and preparation for action in sport56. At the peripheral levels, CAF9 and music60 enhance muscular contractility, through power production increase due to neuromuscular activity’s changes. This is supported by CAF enhancing effects of anabolic processes22 and music activating effects of muscles’ oxygenation61. From a psychological point of view, it is very interesting to highlight that CAF + M condition elicited better physical enjoyment and affective valence compared with their isolate use. A recent meta-analysis reported that affective valence scores were directed toward the positive end of the scale when pre-task music was used26. When considering FAS, warm-up music alone was sufficient to induce greater perceived activation before competing. However, after combat such effects were altered and higher values were recorded under CAF + M condition. This may indicate that the participants started the fight highly energized under music condition, but this effect diminished as the combat progressed62. Therefore, preceding warm-up music by low dose of CAF may extend its effects, may be via its analgesic potential and dopamine stimulation7.

In comparison to males, the complex nature of the scientific framework surrounding the menstrual cycle has been challenging, limiting the development and funding of numerous research studies30. However, CAF13,14 and warm–up music63 ergogenic potentials have been established through the menstrual cycle. Because the most common symptoms experienced during the menstrual cycle are mood changes/anxiety, and tiredness/fatigue64, such results may be reasonable since CAF and music commonly serve to regulate affective and neuromuscular responses9,26,60.

Although the present study provides unique and interesting findings to female athletes, some limitations should be declared. In fact, no neurological or hormonal measurements were conducted to explain the mechanisms under the synergetic effect of CAF and warm-up music. Additionally, the results are presented for the whole menstrual cycle and not according to different phases. Moreover, diet was not controlled during the whole study period and athletes were only asked to maintain their normal diet, which may implicate difference in macronutrient intake between subjects. Finally, for ecological validity matter, self-selected music was used without controlling the genre and synchronization with the performed warm-up.

Conclusions

The present study showed that preceding warm-up music by low dose of CAF induced greater activity profile and more desirable psycho-physiological responses in female taekwondo athletes. In fact, the combine use of these strategies increased the combat intensity whist lowering athletes RPE and HR responses. In addition, CAF + M increased technical actions and guaranteed more desirable psychological responses. Since CAF was supplemented relatively to body mass and the music was preferred, the present study may suggest that using more personalized ergogenic strategies would be effective to cope with competition demands. Furthermore, although this study did not analyze the possible moderating effects of the menstrual cycle phases, benefits under CAF + M condition during the whole menstrual cycle indicated the robustness of their synergistic effects.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank the athletes for their participation in the study.

Author contributions

S.D., I.O., H.M., C.A.B., H.C., and L.P.A. conceived the experiments; S.D., I.O., H.M. and H.C. conducted the experiments; S.D., I.O., H.M., and H.C. analysed the results; and S.D., I.O., H.M., C.A.B., H.C., and L.P.A. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are available from corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Luca Paolo Ardigò and Hamdi Chtourou.

Contributor Information

Ibrahim Ouergui, Email: ouergui.brahim@yahoo.fr.

Luca Paolo Ardigò, Email: luca.ardigo@nla.no.

References

- 1.Bridge CA, da Silva F, Santos J, Chaabène H, Pieter W, Franchini E. Physical and physiological profiles of taekwondo athletes. Sports Med. 2014;44:713–733. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WTF. World Taekwondo Federation, <http://www.worldtaekwondo.org/index.html> (2024).

- 3.Chiodo S, et al. Effects of official Taekwondo competitions on all-out performances of elite athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011;25:334–339. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182027288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridge CA, et al. Repeated exposure to taekwondo combat modulates the physiological and hormonal responses to subsequent bouts and recovery periods. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018;32(9):2529–2541. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilduff LP, Finn CV, Baker JS, Cook CJ, West DJ. Preconditioning strategies to enhance physical performance on the day of competition. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2013;8:677–681. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.8.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López-Torres O, Rodríguez-Longobardo C, Capel-Escoriza R, Fernández-Elías VE. Ergogenic aids to improve physical performance in female athletes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2023;15:81. doi: 10.3390/nu15010081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guest NS, et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Caffeine and exercise performance. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021;18:1. doi: 10.1186/s12970-020-00383-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLellan TM, Caldwell JA, Lieberman HR. A review of caffeine's effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016;71:294–312. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis JK, Green JM. Caffeine and anaerobic performance: Ergogenic value and mechanisms of action. Sports Med. 2009;39:813–832. doi: 10.2165/11317770-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soldin OP, Mattison DR. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin. Pharmacokinetics. 2009;48:143–157. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948030-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mielgo-Ayuso J, et al. Effect of caffeine supplementation on sports performance based on differences between sexes: A systematic review. Nutrients. 2019;11:2313. doi: 10.3390/nu11102313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domaszewski P. Gender differences in the frequency of positive and negative effects after acute caffeine consumption. Nutrients. 2023;15:1318. doi: 10.3390/nu15061318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lara B, Salinero JJ, Giraldez-Costas V, Del Coso J. Similar ergogenic effect of caffeine on anaerobic performance in men and women athletes. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021;60:4107–4114. doi: 10.1007/s00394-021-02510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lara B, Gutierrez Hellin J, Ruiz-Moreno C, Romero-Moraleda B, Del Coso J. Acute caffeine intake increases performance in the 15-s Wingate test during the menstrual cycle. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020;86:745–752. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skinner TL, et al. Factors influencing serum caffeine concentrations following caffeine ingestion. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2014;17:516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamimori GH, et al. The rate of absorption and relative bioavailability of caffeine administered in chewing gum versus capsules to normal healthy volunteers. Int. J. Pharmaceutics. 2002;234:159–167. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(01)00958-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temple JL, Ziegler AM. Gender differences in subjective and physiological responses to caffeine and the role of steroid hormones. J. Caffeine Res. 2011;1:41–48. doi: 10.1089/jcr.2011.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delleli S, et al. Acute effects of caffeine supplementation on physical performance, physiological responses, perceived exertion, and technical-tactical skills in combat sports: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2022;14:2996. doi: 10.3390/nu14142996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arazi H, Hoseinihaji M, Eghbali E. The effects of different doses of caffeine on performance, rating of perceived exertion and pain perception in teenagers female karate athletes. Brazil. J. Pharmaceutical Sci. 2016;52:685–692. doi: 10.1590/s1984-82502016000400012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouergui I, et al. Acute effects of low dose of caffeine ingestion combined with conditioning activity on psychological and physical performances of male and female taekwondo athletes. Nutrients. 2022;14:571. doi: 10.3390/nu14030571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos VGF, et al. Caffeine reduces reaction time and improves performance in simulated-contest of taekwondo. Nutrients. 2014;6:637–649. doi: 10.3390/nu6020637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopes-Silva JP, et al. Caffeine ingestion increases estimated glycolytic metabolism during taekwondo combat simulation but does not improve performance or parasympathetic reactivation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142078–e0142078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delleli S, et al. Effects of caffeine consumption combined with listening to music during warm-up on taekwondo physical performance, perceived exertion and psychological aspects. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0292498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0292498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chtourou H, Hmida C, Souissi N. Effect of music on short-term maximal performance: Sprinters versus long distance runners. Sport Sci. Health. 2017;13:213–216. doi: 10.1007/s11332-017-0357-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terry PC, Karageorghis CI, Curran ML, Martin OV, Parsons-Smith RL. Effects of music in exercise and sport: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2020;146:91–117. doi: 10.1037/bul0000216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delleli S, et al. The effects of pre-task music on exercise performance and associated psycho-physiological responses: A systematic review with multilevel meta-analysis of controlled studies. Front. Psychol. 2023;14:1293783. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1293783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouergui I, et al. The effects of tempo and loudness variations during warm-up with music on perceived exertion, physical enjoyment and specific performances in male and female taekwondo athletes. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0284720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0284720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouergui I, et al. Listening to preferred and loud music enhances taekwondo physical performances in adolescent athletes. Percept. Mot. Skills. 2023 doi: 10.1177/00315125231178067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruinvels G, et al. Sport, exercise and the menstrual cycle: Where is the research? Br. J. Sports Med. 2017;51:487. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sims ST, et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Nutritional concerns of the female athlete. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2023;20:2204066. doi: 10.1080/15502783.2023.2204066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doherty M, Smith PM. Effects of caffeine ingestion on rating of perceived exertion during and after exercise: A meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2005;15:69–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daly J. Caffeine analogs: Biomedical impact. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:2153–2169. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7051-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bühler E, Lachenmeier D, Schlegel K, Winkler G. Development of a tool to assess the caffeine intake among teenagers and young adults. Ernahrungs Umschau. 2014;61:58–63. doi: 10.4455/eu.2014.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karageorghis CI, Priest DL, Terry PC, Chatzisarantis NL, Lane AM. Redesign and initial validation of an instrument to assess the motivational qualities of music in exercise: The Brunel Music Rating Inventory-2. J. Sports Sci. 2006;24:899–909. doi: 10.1080/02640410500298107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diaz-Lara FJ, et al. Enhancement of high-intensity actions and physical performance during a simulated Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu competition with a moderate dose of caffeine. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2016;11:861–867. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2015-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chtourou H, Trabelsi K, Ammar A, Shephard RJ, Bragazzi NL. Acute effects of an “energy drink” on short-term maximal performance, reaction times, psychological and physiological parameters: Insights from a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled. Counterbalanced Crossover Trial. Nutrients. 2019;11:992. doi: 10.3390/nu11050992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borg, G. An introduction to Borg’s RPE-scale. Mouvement Publications. https://books.google.tn/books?id=2AjwNwAACAAJ (1985).

- 38.Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ. Physical activity enjoyment scale: Two validation studies. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1991;13:50–64. doi: 10.1123/jsep.13.1.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hardy CJ, Rejeski WJ. Not what, but how one feels: The measurement of affect during exercise. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1989;11:304–317. doi: 10.1123/jsep.11.3.304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svebak S, Murgatroyd S. Metamotivational dominance: A multimethod validation of reversal theory constructs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985;48:107–116. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hopkins WG. A scale of magnitudes for effect statistics. N. View Statist. 2002;502:411. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomczak, M. & Tomczak, E. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends Sport Sci.21 (2014).

- 43.Kazemi M, Ong M, Pacis A, Tseng K. A profile of 2012 olympic games taekwondo athletes. Acta Taekwondo et Martialis Artium (JIATR) 2014;1:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- 44.da Silva Santos JF, Franchini E. Frequency speed of kick test performance comparison between female taekwondo athletes of different competitive levels. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018;32(10):2934–2938. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ouergui I, et al. Acute effects of caffeine supplementation on taekwondo performance: The influence of competition level and sex. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:13795. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-40365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krabben K, Orth D, van der Kamp J. Combat as an interpersonal synergy: An ecological dynamics approach to combat sports. Sports Med. 2019;49:1825–1836. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01173-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwok HHM. Discrepancies in fighting strategies between Taekwondo medalists and non-medalists. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2012;7:806–814. doi: 10.4100/jhse.2012.74.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kazemi M, Waalen J, Morgan C, White AR. A profile of olympic taekwondo competitors. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2006;5:114–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glaister M, Gissane C. Caffeine and physiological responses to submaximal exercise: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018;13:402–411. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2017-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stratton VN, Zalanowski AH. The relationship between music, degree of liking, and self-reported relaxation. J. Music Therapy. 1984;21:184–192. doi: 10.1093/jmt/21.4.184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gavanda S, et al. The influence of relaxing and self-selected stimulating music on vertical jump performance in male volleyball players. Int. J Exerc. Sci. 2022;15:15–24. doi: 10.70252/PFNC1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bigliassi M, Leon-Dominguez U, Buzzachera CF, Barreto-Silva V, Altimari LR. How does music aid 5 km of running? J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015;29:305–314. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pethick J, Winter SL, Burnley M. Caffeine ingestion attenuates fatigue-induced loss of muscle torque complexity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017;50:236–245. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herrera-Valenzuela T, et al. Physical and physiological profile of young female taekwondo athletes during simulated combat. Ido Movement Culture. J. Martial Arts Anthropol. 2015;4:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cortez L, Mackay K, Contreras E, Penailillo L. Acute effect of caffeine ingestion on reaction time and electromyographic activity of the Dollyo Chagi round kick in taekwondo fighters. RICYDE: Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte. 2017;13(47):52–62. doi: 10.5232/ricyde2017.04704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bishop DT, Wright MJ, Karageorghis CI. Tempo and intensity of pre-task music modulate neural activity during reactive task performance. Psychol. Music. 2013;42:714–727. doi: 10.1177/0305735613490595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haddad M, et al. The construct validity of session RPE during an intensive camp in young male taekwondo athletes. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2011;6:252–263. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.6.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marques M, Staibano V, Franchini E. Effects of self-selected or randomly selected music on performance and psychological responses during a sprint interval training session. Sci. Sports. 2022;37(139):e131–139.e110. doi: 10.1016/j.scispo.2021.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang B, Liu Y, Wang X, Deng Y, Zheng X. Cognition and brain activation in response to various doses of caffeine: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:1393. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordon CL, Cobb PR, Balasubramaniam R. Recruitment of the motor system during music listening: An ALE meta-analysis of fMRI data. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamamoto T, et al. Effects of pre-exercise listening to slow and fast rhythm music on supramaximal cycle performance and selected metabolic variables. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2003;111:211–214. doi: 10.1076/apab.111.3.211.23464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hutchinson JC, et al. The influence of asynchronous motivational music on a supramaximal exercise bout. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2011;42:135–148. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghazel N, Souissi A, Chtourou H, Aloui G, Souissi N. The effect of music on short-term exercise performance during the different menstrual cycle phases in female handball players. Res. Sports Med. 2022;30:50–60. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2020.1860045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bruinvels G, et al. Prevalence and frequency of menstrual cycle symptoms are associated with availability to train and compete: A study of 6812 exercising women recruited using the Strava exercise app. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021;55:438–443. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed during this study are available from corresponding author.