Abstract

Background

Depression among young people is a global health problem due to its rising prevalence and negative physical and social outcomes. The prevalence of depression and the treatment gap among young people in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is higher than global estimates. Most psychosocial interventions for adolescent and youth depression were developed in high-income countries and less is known about their effectiveness in SSA. Due to contextual differences, findings from High-Income Countries (HICs) are less applicable to SSA. Yet, no systematic review of psychosocial interventions for depression among young people in SSA has been conducted.

Methods

A systematic literature search of four databases (Medline, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and Cochrane library) was conducted. Experimental studies published before May 2024 that evaluated the effect of psychosocial interventions on depressive symptoms among young people (aged 10–24 years) in SSA were included in the systematic review. Effect sizes (Hedge’s g (g)) indicating differences between intervention and control groups were calculated using a random effects model.

Results

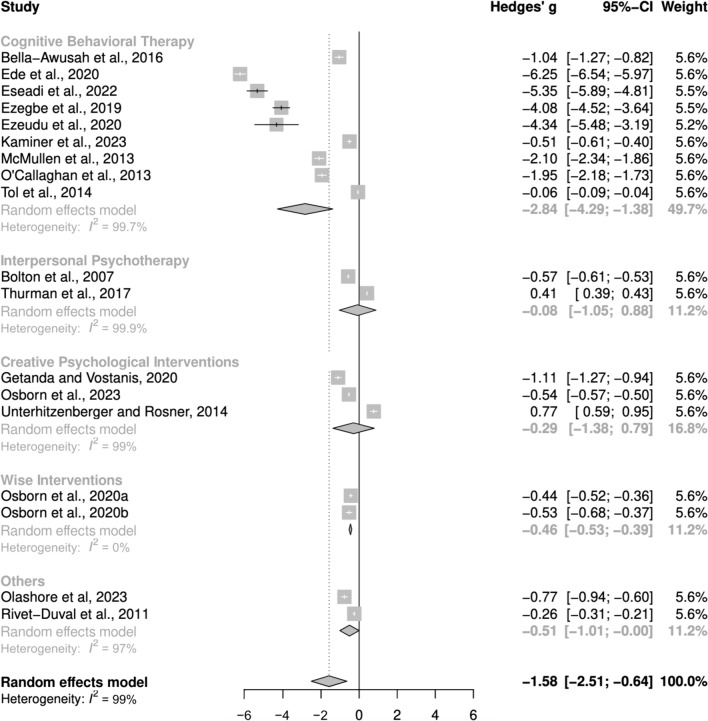

Twenty-two eligible studies were identified for the systematic review, of which eighteen randomized control trials (RCTs) involving 2338 participants were included in the meta-analysis. The findings revealed that psychosocial interventions significantly reduced depressive symptoms (g = −1.55, 95% CI −2.48, −0.63), although heterogeneity was high (I2 = 98.8%). Subgroup analysis revealed that efficacy differed significantly by intervention type, with Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (9 studies) showing the strongest effect (g = −2.84, 95% CI −4.29; −1.38). While Wise Interventions (a form of positive psychology interventions; 2 studies) had a moderate effect (g = −0.46, 95% C.I −0.53, −0.39), Interpersonal Psychotherapy (2 studies; g = −0.08, 95% CI −1.05, 0.88) and Creative Psychological Interventions (3 studies; g = −0.29, 95% CI −1.38, 0.79) showed smaller, non-significant effects. Sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias strengthened the effect size. Few studies assessed factors affecting intervention efficacy and showed mixed effects of age, gender, and adherence levels.

Conclusion

Psychosocial interventions, particularly CBT, significantly reduced depressive symptoms among young people in SSA. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the high heterogeneity which likely stems from variations in study populations and intervention delivery modalities. This highlights the need for further research to identify the specific intervention components and delivery methods that work best for distinct subpopulations. Future research should also explore how long intervention effects are maintained and factors affecting efficacy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13033-024-00642-w.

Keywords: Depression, Mental health, Adolescents, Youth, Young people, Psychosocial interventions, Psychological therapy, Cognitive behavioral therapy, Interpersonal psychotherapy, Sub, Saharan Africa (SSA), Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Background

Depression is a global health issue

Depression is a common mental disorder that affects about 280 million people globally and is the second leading cause of disability worldwide [1, 2]. Depression is a mood disorder characterized by a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that affect an individual’s ability to function [3]. The lifetime prevalence of depression varies by sex and region, ranging from 2.6% among males in the World Health Organization (WHO) Western Pacific Region to 5.9% among females in the WHO African Region [Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)] [4]. The forty-eight African countries that lie south of the Sahara make up SSA. It is the poorest region in the world and contains twenty-four of the twenty-seven countries in the World Bank’s Low-income classification [5]. Although the estimated prevalence of depression in SSA is considerably high, the true prevalence is possibly higher due to underdiagnosis caused by stigma, paucity of mental health services, and inadequate research [6]. About 75–90% of people with depression and other mental disorders in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) do not receive treatment [7, 8]. This “treatment gap” is higher in many SSA countries. For instance, it is 99.8% in Sierra Leone [9]. Lack of treatment despite increasing prevalence results not only in disability but also productivity losses, which cost the global economy $1trillion annually [10].

Depression among young people

The term "young people" refers to adolescents and youths. Adolescents are young people aged 10 to 19, while youths are between ages 15 and 24 [11]. Depression is the second most prevalent mental disorder among young people [2] and warrants increased attention for the following reasons. First, depression usually starts during adolescence and persists into adulthood, especially when undiagnosed or inadequately treated. Research shows that 50% of Common Mental Disorders (CMDs) appear by age 14 and three-quarters by age 24 [12]. The prevalence of depression is low in children (1%), then rises substantially during adolescence, especially among females [13]. This observed increase is attributable to the sociobiological changes typical of the post-pubertal phase, such as increased social understanding and self-awareness, changes to the brain circuits involved in responses to reward and danger, and elevated stress [14, 15]. Secondly, the prevalence of adolescent depression is rising. A recent meta-analysis revealed that the global point prevalence of depression in young people (25.2%) had doubled from pre-pandemic estimates [16]. The pandemic exacerbated an already rising prevalence observed in both High Income Countries (HICs) and LMICs over the last two decades [17–20]. Currently, the point prevalence of adolescent depression in LMICs ranges from 18% in China to 51% in Zambia [21]. Thirdly, the negative consequences of depression in young people are enormous. Adolescent depression is a major risk factor for suicide, which is a leading cause of death among young people, particularly in LMICs [22]. Furthermore, depression is associated with self-harm, substance use, risky sexual behaviour, and poor educational attainment [23, 24]. Although prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment can reduce its high burden and negative outcomes, 80% of young people with CMDs in LMICs and almost 100% in many SSA countries do not get the care they need [25].

Depression among young people in Sub-Saharan Africa

Young people account for a third of SSA’s population [26]. One in ten young people in SSA suffers from CMDs, particularly anxiety and depression [27]. A recent systematic review estimated the point prevalence of depression among young people in SSA at 26.7% and shows that the prevalence in many SSA countries is higher than the global estimate [28]. This is likely due to contextual risk factors such as poverty, conflict, poor healthcare, HIV, and teenage pregnancy, in addition to those common in HICs (e.g., parental psychopathology) [27]. Despite this, only nine of the forty-eight countries in SSA have comprehensive policies for adolescent mental health, resulting in huge barriers to care [29]. It is on this premise that WHO, in its landmark World Mental Health Report, calls for contextually appropriate, cost-effective interventions for adolescent depression in SSA [22]. For every $1 invested in these interventions, Stelmach et al. expect $125 in health and economic benefits returned to the regional economy [25].

Psychosocial interventions for depression in young people

Psychosocial Interventions for mental disorders are interpersonal or informational activities/techniques that influence outcome through changes in mediating biopsychosocial factors. They include psychological therapies like Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) and Psychodynamic therapy, and social interventions like peer support services and skill building [30]. Psychosocial interventions are the first-line approach for depression in young people and antidepressants should be used only in cases unresponsive to psychological therapy [31, 32]. Research over the years have established the efficacy of psychosocial interventions in the treatment of adult depression [33–35]. Given this evidence, different interventions have been adapted for adolescent and youth populations. CBT and IPT are the most extensively tested in young people and reviews have shown that they reduce depressive symptoms [36–38]. Attachment-based family therapy, though less extensively researched, has also shown some positive effect [39]. These interventions have proven effective when delivered in individual and group formats [40, 41] and via bibliotherapy or technology-assisted methods, although to varying degrees [42, 43]. They have also been delivered in different settings, such as schools and communities [38].

Majority of the studies that established these interventions as evidence-based were conducted in HICs and less is known about their effectiveness in LMICs. In recent years, these interventions have increasingly been tested in LMICs. Findings show that interventions developed in HICs might not be acceptable, feasible, or effective in LMICs due to contextual differences such as dissimilar cultural perceptions of depression, and barriers to care (e.g., low awareness, insufficient mental health workers, stigma, and poverty) [44]. Innovative solutions like task-shifting (use of non-mental health professionals), cultural adaptation, and the use of digital technologies have been tested with mixed results [45, 46]. There is a need to understand how these interventions are adapted to fit different contexts and how these modifications affect their effectiveness. Systematic reviews of LMICs involve only a few SSA countries, thus limiting their applicability to the region [44, 47, 48]. Though it remains unclear which psychosocial interventions are most effective in the region, no systematic review has been conducted on this topic. This review aims to identify and describe psychosocial interventions for depression among young people in SSA, determine their efficacy and explore factors that affect their efficacy. As most SSA countries do not have policies for young people’s mental health, findings from this study will contribute to future research and policy development.

Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [49] [Additional Files 1, 2].

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed with the assistance of a research librarian and the systematic database search was first conducted in July 2022 (updated May 2024) with keywords identified using the PICO framework [50] (Table 1). The keywords with their MeSH terms and synonyms were combined with Boolean operators (“AND” and “OR”) and wildcards (*, ?) to run a comprehensive search on Medline (OVID). This search strategy was then adapted to Web of Science, PsycInfo and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The detailed search strategy for each database is shown in Additional File 3. The reference lists of included articles were also searched to identify other relevant papers.

Table 1.

Identification of search terms using PICO framework

| PICO component | Keywords | MeSH term and synonyms |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

Young people Sub-Saharan Africa |

MeSH: adolescent Synonyms: Adolescent* OR Teenager* OR Teen* OR youth* OR young person OR young people OR youngster* OR young adult* OR student* OR high school OR college OR secondary school MeSH: Africa South of the Sahara Synonyms: Sub-Saharan Africa OR SSA OR West* Africa OR East* Africa OR South* Africa OR Central Africa OR ( +) |

| Intervention |

Psychosocial Intervention |

MeSH: psychotherapy Synonyms: psychosocial OR psychological OR psychoeducation OR behavioural therapy OR cognitive behavioural therapy OR CBT OR Interpersonal Psychotherapy OR IPT OR problem-solving therapy OR counselling OR narrative therapy Synonyms: Treatment OR Therapy OR Trial OR Project OR Program* |

| Outcome | Depression |

MeSH: depression; depressive disorder Synonyms: depression or depressive disorder* or dysthymia or depressive symptom |

( +) – List of all Sub-Saharan African countries with “OR” between them

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were generated using the PICOS framework [50], as shown in Table 2. Studies that reported the effect of various psychosocial interventions on depressive symptoms in any adolescent or youth population in SSA were included. To best capture the state and quality of research, papers were not included or excluded based on study design or quality assessment. Due to limited resources for translation, only papers in English language were included.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| PICO component | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

• Study population including young people (WHO definition: 10–24 years) • Young people (adolescents and youth) in SSA |

• Primarily children or adult population • Study population outside 10–24 years • Young people living in non SSA countries |

| Intervention |

• Studies on psychosocial interventions for depression • Intervention aimed at reducing depressive symptoms |

• No intervention or pharmacological and other types of interventions • Intervention not focused on reducing depressive symptoms |

| Comparison |

• All types of control arms • Quasi-experimental studies without control groups |

• No exclusion based on use or characteristics of control group |

| Outcome |

• Study reports outcome on depressive symptoms • Standardized instruments used to diagnose elevated depressive symptoms |

• Study does not report outcome on depressive symptoms • Standardized instruments not used |

| Study design | • Primary experimental studies using different study designs (not limited to RCTs) | • Systematic reviews and meta-analysis |

| Others |

• Studies reported in English language • Studies published in peer-reviewed journals |

• Studies reported in other languages • Not peer-reviewed papers, grey literature¸ non-academic papers (commentaries, editorials, etc.), books, book chapters |

Data management and extraction

All records captured by the search terms were exported to EndNote 20 Library. After de-duplication, titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers (LO and EU). Papers that did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded. The full texts of the remaining papers were screened by same reviewers against the eligibility criteria. A data extraction form was developed to extract relevant information from the papers such as country, study design, intervention setting, screening instrument, intervention characteristics, and outcome (depressive symptoms pre- and post-intervention). Three tables were developed from this form and are presented in the results section.

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tools for randomized control trials (RCTs) version 2 (RoB2) and Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) were used to assess the risk of bias (RoB) for RCTs and Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (NRSI) respectively [50]. These specific RoB tools were used due to the methodological differences between study designs, particularly randomization which is an important consideration in judging bias. For RCTs, six RoB domains (randomization process, deviation from intended intervention, missing outcome data, measurement of outcome, and selective reporting) were assessed and studies judged to have high, “some concerns” or low RoB. For NRSI, six domains (confounding, participant selection, deviation from intervention, missing data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting) were assessed. Studies were judged as having a low, moderate, serious, or critical risk of bias [50].

Meta-analysis

The meta-analysis included clinical trials wherein participants were randomly allocated to either receive a psychosocial intervention or be placed in control conditions, with depression scores reported as an outcome. Statistical analysis was performed using R software (version 4.3.1) and the metafor package (version 4.4.0). To ensure uniformity and reproducibility of results, standardized mean differences (SMD) alongside 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were calculated for each study using extracted data (mean and standard deviation). SMDs were employed because studies used different screening instruments to evaluate depression scores [50]. Pre- to post-intervention changes were analysed but follow-up impacts were not considered due to a lack of information in some studies and variations in follow-up periods. Effect sizes (SMD) were calculated using Hedges’ g because it corrects for small sample bias. This was pertinent given the relatively small sample sizes in some included studies [51]. Effect size magnitudes were categorized as small (0.20–0.50), moderate (0.50–0.80), and large (> 0.80) based on Cohen's rule of thumb [52]. A random-effects model was used a priori to account for expected heterogeneity among studies, including variations in intervention types, delivery modalities, participant characteristics, and screening instruments. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and I2. An I2 value of 0 to 25% can be considered as low, 50% as moderate and 75% and above as a high level of heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis was pre-determined to explore variations in psychosocial interventions [52]. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding studies with high risk of bias to assess the robustness of findings. Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot and Egger’s regression test [53].

Results

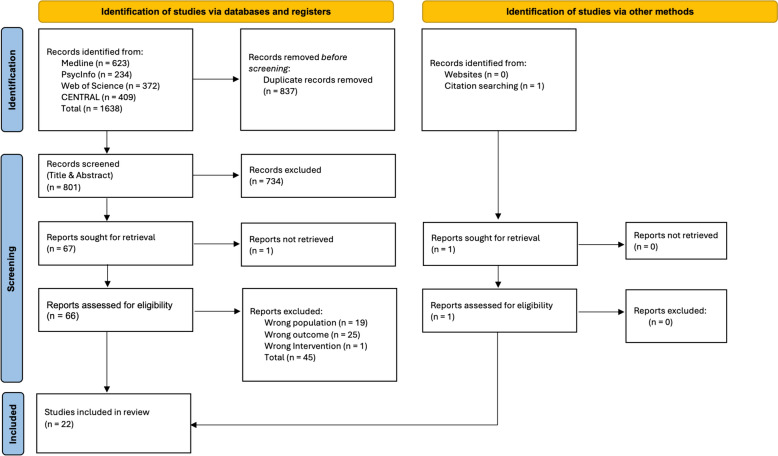

The search strategy identified 1,638 papers across the four databases. After de-duplication and title and abstract screening, 67 papers were sought for full-text screening. One could not be retrieved despite attempts to contact the author. Forty-five papers were excluded after full-text screening and one paper was identified via citation searching. Reasons for exclusion are listed in Additional File 4. Hence, a total of 22 studies were included in the review. The PRISMA Diagram illustrates the selection process (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating steps to paper selection

Description of included studies

The twenty-two included studies were conducted across ten different SSA countries; nine in Nigeria [54–62], four in Kenya [63–66], two each in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) [67, 68] and South Africa [69, 70] and one each in Botswana [71], Burundi [72], Mauritius [73], Rwanda [74], and Uganda [75]. Ninteen studies were RCTs, while three were NRSIs. Among the NRSI, one was a controlled clinical trial (CCT) [55] while two were pre-post intervention studies [54, 61]. Seventeen studies included only adolescents while the other six included youths. Table 3 shows the important characteristics of all included studies. The studies were carried out in different settings and targeted different populations. Most studies (fourteen) were conducted in schools; nine in secondary schools, and six in tertiary institutions. While the majority of interventions included the general student population, others targeted specific populations with increased risk of depression such as students with sickle cell disease in Nigeria (SCD) [54], internally displaced [63] and students from low-income families in Kenya [64–66], and orphaned students in Rwanda [74]. Among the non-school-based interventions, three were delivered in clinics to adolescents living with HIV in Botswana [71], trauma-exposed adolescents in South Africa [70] and depressed adolescents attending a psychiatric clinic in Nigeria [61]. The others were delivered in communities to war-affected adolescents in DRC [67, 68, 75] and orphans of the HIV epidemic in South Africa [69]. Some studies excluded participants with co-morbid psychiatric disorders, substance use, intellectual difficulties, and suicidality [55, 56, 60, 62, 68, 74]. Others also excluded participants based on depression screening. For example, while Are et al. [55] excluded people with severe depression, Eseadi et al. [58] included only individuals with moderate-to-severe depression. In contrast, three studies did not apply these exclusion criteria [64, 65, 67]. McMullen et al. noted that this was done to “keep the trial as naturalistic as possible” [67]. Overall, eleven studies had relatively small sample sizes (less than 60).

Table 3.

Description of included studies

| References | Study location | Study design | Study setting | Sample population | Sample Size | Screening instrument | Length of follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adegbolagun et al. [54] | Nigeria | Quasi-experimental (Pre-Post Intervention) | University Health Centre | Students with sickle cell disease aged 16–24 years | 20 | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | None |

| Are et al. [55] | Nigeria | Controlled clinical trial | Secondary School | Students aged 13–18 years with clinically diagnosed depression | 40 | Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI) | None |

| Bella-Awusah et al. [56] | Nigeria | Randomized control trial | Secondary School | Students aged 14–17 years | 40 | Beck's Depression Inventory | 16 weeks |

| Bolton et al. [75] | Uganda | Randomized control trial | Internally Displaced People (IDP) camps | Adolescent survivors of war and displacement aged 14–17 years | 314 | Acholi Psychosocial Assessment Instrument (APAI) | None |

| Ede et al. [57] | Nigeria | Randomized control trial | College of Education students | College students aged 15–25 years | 162 | Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) | 12 weeks |

| Eseadi et al. [58] | Nigeria | Randomized control trial | University Campus | University students | 67 | Beck's Depression Inventory | 2 weeks |

| Ezegbe et al. [59] | Nigeria | Randomized control trial | University Campus | Undergraduate social science students | 55 | Goldberg Depression Scale (GDS) | 12 weeks |

| Ezeudu et al. [60] | Nigeria | Randomized control trial | University Campus | Undergraduate chemistry students | 23 | Beck's Depression Inventory | Not reported |

| Getanda and Vostanis [63] | Kenya | Randomized CONTROL TRIAL | Secondary School | Internally Displaced adolescents aged 14–17 years | 54 | Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children (DSRS) | 1 week |

| Isa et al. [61] | Nigeria | Quasi-experimental (Pre-Post Intervention) | Psychiatric hospital | Clinically depressed adolescents aged 13–18 years | 18 | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) | 4 weeks |

| Kaminer et al. [70] | South Africa | Randomized control trial | University-based trauma research clinic | Trauma-Exposed Adolescents aged 11–19 years | 75 | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | 12 weeks |

| McMullen et al. [67] | Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) | Randomized control trial | Re-Orientation Centre for former child soldiers | Former boy soldiers aged 13–17 years | 50 | African Youth Psychosocial Assessment Instrument (AYPA) (formerly known as the Acholi Psychosocial Assessment Instrument) | 12 weeks |

| O'Callaghan et al. [68] | DRC | Randomized control trial | Local vocational training centre | War-affected sexually abused girls aged 12–17 years | 52 | African Youth Psychosocial Assessment Instrument (AYPA) | 12 weeks |

| Ofoegbu et al. [62] | Nigeria | Randomized control trial | University Campus | University students | 192 | Beck's Depression Inventory | 4 weeks |

| Olashore et al. [71] | Botswana | Randomized control trial | HIV Clinic | Adolescents living with HIV, aged 15 to 19 | 50 | Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-9) | 24 weeks |

| Osborn et al. [65] | Kenya | Randomized control trial | Secondary School for low-income students | Secondary school students aged 13–18 years | 103 | Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) | 2 weeks |

| Osborn et al. [64] | Kenya | Randomized control trial | Secondary School in an urban slum | Secondary school students aged 12–19 years | 51 | Patient Health Questionnaire-8 | None |

| Osborn et al. [66] | Kenya | Randomized control trial | High schools in an impoverished urban neighbourhood | Grade 9–11 High school students aged 13–19 years | 235 | Patient Health Questionnaire–8 | 4 weeks |

| Rivet-Duval et al. [73] | Mauritius | Randomized control trial | Secondary School | Secondary school students aged 12–16 years | 160 | Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale—2 (RADS-2) | 24 weeks |

| Thurman et al. [69] | South Africa | Randomized control trial | Community-based program | HIV orphaned and vulnerable adolescents 14–17 years | 489 | Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) | 48 weeks |

| Tol et al. [72] | Burundi | Cluster randomized control trial | Secondary school in war-torn area | War-affected secondary school students | 329 | Depression Self-Rating Scale for Children (DSRS) | 12 weeks |

| Unterhitzenberger and Rosner [74] | Rwanda | Randomized control trial | Orphanage's boarding school | Orphaned adolescents aged 14–18 years | 69 | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents, Part A, on depression (MINI-KID A) | None |

Nine different screening instruments were used to assess depressive symptoms, with Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) being the most used. All the instruments, except the Acholi Psychosocial Assessment Instrument (APAI), were developed in western countries. APAI was developed and used in Uganda by Bolton et al. [75]. It was modified into the AYPAI and used in the two DRC studies. The reliability of APAI was 84%, similar to BDI, while AYPAI was 74% [67, 68].

All but five studies [54, 55, 65, 74, 75] reported mean depressive symptoms after a follow-up period (Table 3). The majority of studies adopted a three-month follow-up period [57, 59, 67, 68, 72]. The longest follow-up period was twelve months [69] while the shortest was 1 week [63]. One study had no follow-up [65] while another [60] did not report the length of follow-up.

Intervention characteristics

The majority of studies (13) tested the effect of CBT-based interventions on depressive symptoms [54–62, 67, 68, 70, 72]. Two studies each exammined the effects of Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) [69, 75] and Wise Interventions (WI) [64, 65]. Three studies tested Creative Psychological Interventions (CPI) such as Expressive Writing (EW) [63, 74] and arts-based therapy [66]. The other interventions combined two psychotherapautic approaches. The Resourceful Adolescent Program (RAP), a universal preventive programme, combined both IPT and CBT techniques [73] while the intervention by Olashore et al. [71] combined psychoeducation and problem-solving. Table 4 shows the important intervention characteristics of each study.

Table 4.

Intervention characteristics

| References | Intervention (Number of participants) | Control (Number of participants) | Intervention description/details | Frequency and duration | Delivery format and modality | Delivery personnel/facilitators | Cultural and contextual adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adegbolagun et al. [54] | Group CBT (18) | NA | A manualized CBT intervention with sessions on management of negative thoughts and feelings, activity scheduling, relaxation techniques, and attention diversion. Content adapted to reflect realities of living with Sickle Cell Disease | Weekly sessions for 5 weeks |

Group Face to Face |

Primary care physician with postgraduate training in adolescent mental health | Unspecified content adaptation to suit local culture. Sessions scheduled on weekends only to suit student’s academic schedule. Sessions condensed from 12 to 5 to enhance feasibility |

| Are et al. [55] | Group CBT (20) | Waitlist (20) | A manualized CBT intervention focused on psychoeducation, behavioural activation, activity scheduling, and relaxation strategies | 1 h weekly sessions for 5 weeks |

Group Face to Face |

Teachers trained and supervised by a psychiatrist | Manual adapted to include local metaphors and exemplars. Encouragement of helpful pre-existing cultural and religious coping strategies used by both Christians and Muslims in Nigeria. Manual translated to local language (Hausa). Intervention delivered during school hours to encourage adherence |

| Bella-Awusah et al. [56] | Group CBT (20) | Waitlist (20) | A manualized CBT program with sessions on psychoeducation, behavioural activation, activity scheduling and relaxation techniques | 45–60 min weekly sessions for 5 weeks |

Group Face to Face |

Consultant Psychiatrist with training in CBT | Manual included religious-based coping strategies and cultural analogies used in the local population. Sessions delivered in both English and local language (Yoruba) |

| Bolton et al. [75] | Group IPT (105) | Creative Play (105), Waitlist (104) | A manualized IPT intervention focused on identifying and dealing with interpersonal triggers and group relationship building | 1.5-2 h weekly sessions for 16 weeks |

Group Face to Face |

Lay facilitators trained and supervised by mental health experts | Adapted to local culture (Acholi). Use of locally developed screening instrument (APAI) which reflects cultural perception of depression |

| Ede et al. [57] | Group CBT (82) | Waitlist (80) | A manualized CBT intervention which focused on cognitive restructuring (identifying, challenging, and modifying maladaptive schematic beliefs associated with depression) | 1 h weekly sessions for 12 weeks |

Group Face to Face |

Experienced adolescent mental health counsellors | Sessions delivered in English and local language (Igbo). Manual otherwise not adapted |

| Eseadi et al. [58] |

Rational Emotive Behavioural Therapy (REBT) (34) |

Waitlist (33) | Religious REBT techniques, in addition to general REBT techniques for treatment of depression, were used. Incorporated scriptural contents and religious resources relevant to the students' religious traditions and orientations | 2-h weekly sessions of 12 weeks | Group Face-to-face | NR | Adapted to incorporate religious philosophies and traditions of the undergraduate religious education students in Southern Nigeria |

| Ezegbe et al. [59] | Group CBT (28) | Waitlist (27) | CBT manual addressed mood monitoring techniques, cognitive restructuring, relaxation, reframing and problem-solving techniques | 2 h weekly sessions for 12 weeks |

Group Face to Face |

Professional therapists | None |

| Ezeudu et al. [60] |

Rational Emotive Behavioural Therapy (REBT) (12) |

Usual care (11) |

Group REBT Depression Manual used cognitive, behavioural, and emotive techniques to assist patients in identifying and altering irrational and self-defeating thoughts and beliefs which result in depression | Weekly sessions for 12 weeks |

Group Face to Face |

NR | None |

| Getanda and Vostanis [63] | Writing for Recovery (WfR) (27) |

Waitlist (27) |

A psycho-social-educational structured writing intervention which adopted a testimonial/narrative approach | Six sessions over three days |

Group Face to Face |

Paraprofessionals (with social care background) | Involvement of community stakeholders like schoolteachers, parents and religious leaders in intervention planning and implementation. Delivery of intervention in local Swahili language |

| Isa et al. [61] | Group CBT (18) | NA | A group-based manualised intervention focused on psychoeducation and basic CBT strategies (positive self-talk and behavioural activation) | 30–40 min weekly sessions for four weeks | Group. Face to Face | Psychiatrist |

Used manual developed by Nigerian experts to suit the local context Sessions delivered in commonly used local language (simplified Pidgin English) |

| Kaminer et al. [70] | Trauma-focused CBT (37) | Treatment as Usual (38) | An abbreviated 8-session version of TF-CBT, retaining all components of the original 12–15 session model but condensed into fewer sessions. Components included psychoeducation, relaxation skills, affective modulation, cognitive coping skills, trauma narrative and cognitive processing, enhancing safety, and caregiver sessions focused on parenting skills | 90 min sessions weekly sessions for eight weeks | Individual. Face to Face | Registered mental health professionals (psychological counselors and clinical psychologists) trained in TF-CBT | Abbreviated to 8 sessions to align with resource constraints in South African. Manual adapted to suit local context. The adapted manual emphasises asking participants to generate examples from their own life on which to practice the various skills, to ensure that practice examples are con-textually relevant for South African participants |

| McMullen et al. [67] | Group Trauma-focused CBT (25) | Waitlist (25) | A manualized Trauma Focused-CBT intervention focused on psychoeducation, relaxation techniques, affect expression, cognitive restructuring, trauma narration, and coping | 15 sessions over five weeks | Group. Face to Face | Experienced foreign and local mental health experts |

Manual modified to include culturally applicable analogies and exemplars. Local games and songs used to help the participants relax, learn social skills, and participate in group activities. Screening instrument modified to fit the context and language (Swahili) Use of local interpreters |

| O'Callaghan et al. [68] | Group Trauma-focused CBT (24) | Waitlist (28) | A manualized Trauma Focused-CBT intervention focusing on psychoeducation, stress management, affect expression and modulation, and cognitive restructuring and coping | 15 sessions over five weeks | Group. Face to Face | Local (Congolese) social workers |

Cultural adaptations included having a female facilitator talk about ways to reduce the risk of sexual violence (e.g., fetching firewood with a friend); the use of culturally familiar games, songs, and examples (e.g., belief that a neighbour is a witch); and social workers visiting the girl’s guardians to foster family acceptance and reduce stigmatization Screening Instrument modified to Swahili |

| Olashore et al. [71] | Psychoeducation and Problem-solving (25) | Waitlist (25) | The intervention involved interactive discussion, role-play, and brief plenary sessions. It included psychoeducation on HIV, depression, stigma, identifying problems, guided problem-solving, increasing pleasurable activities, mood monitoring, and rehearsing adaptive adherence strategies | 1 h weekly sessions for 5 weeks | Group. Face to Face | Trained graduate psychology counsellor supervised by the principal investigator | Adapted from interventions designed in high-income countries using locally relevant video vignettes, illustrations and case examples in Setswana and English |

| Ofoegbu et al. [62] | Guided Internet Assisted Intervention (96) | Usual care (96) | A Guided internet-assisted intervention that covered psychoeducation, cognitive disputation, behavioural homework assignments, and role-play. The guidance therapists provided twice-a-week and on-request assistance within the portals, and through email and telephone. Guidance involved helping participants find useful resources | 10 weeks | Individual. Internet-based | Guided self -help (Guidance by therapists) | None |

| Osborn et al. [65] | “Shamiri” Digital Intervention (50) | Study skills (53) | A Single Session Digital Intervention which consisted of three modules: growth mindset, gratitude, and value affirmation, based on principles of Wise Interventions. Study skills (control) consisted of two modules: note-taking skills and effective study habits | 1 h Single session | Individual. Computer-based | Self-help | Local stakeholders (school administrators, students, and community members) were extensively involved in the development and adaptation process to ensure that the intervention was socio-culturally appropriate for the Kenyan context. Use of locally familiar examples and metaphors |

| Osborn et al. [64] | “Shamiri” Group Intervention (28) | Study skills (24) | A combination of three Wise Interventions (growth mindset, gratitude, and value affirmation). Each session included reading and writing activities, group discussions, and homework. Control group content focused on study skills such as note-taking, effective reading strategies, and time management | 1 h weekly sessions for four weeks | Group. Face to Face | High school graduates trained as lay providers | Group discussions in either English or Kiswahili. Intervention adapted through an iterative process that took local culture and customs into consideration |

| Osborne et al. [66] | “Pre-Texts” Arts-literacy intervention (106) | Study skills. (129) | Creative Arts-literacy interventions employ art-based psychotherapeutic approaches to facilitate psychological change. Pre-Texts utilized text—such an “excerpt from a novel, a physics lesson, or a technical manual—to inspire art-making”. This is followed by a collective reflection on the process of interpretation through artmaking | 1 h daily sessions for one week | Group. Face-to-Face | High school graduates trained as lay providers | Students were encouraged to use local arts, languages, traditions, and tastes as resources for learning to make the intervention more engaging and relevant to their own lives |

| Rivet-Duval et al. [73] | Resourceful Adolescent Program- Adolescent version (RAP-A) (80) | Waitlist (80) | A manualised universal based program which included both CBT and IPT approaches covering topics such as building self-esteem, keeping calm, thinking resourcefully, problem solving, considering the perspective of others and keeping the peace | 1 h weekly sessions for 11 weeks | Group. Face to Face | School Teachers | None |

| Thurman et al. [69] | Group Interpersonal Psychotherapy (260) | Usual care (229) | Intervention utilized an IPT-G manual which focused on four interpersonal areas that trigger depressive symptoms: grief, interpersonal disputes, role transitions, and relationship deficits | 1.5 h min weekly sessions for 16 weeks | Group. Face to Face | Lay facilitators recruited from the community | None |

| Tol et al. [72] | Group CBT techniques + Creative Expressive elements (153) | Waitlist (176) | A manualized intervention which consisted of cognitive behavioural techniques (psychoeducation, coping, trauma narration, future planning, social reconnection) and creative expressive elements (cooperative games, structured movement, music, drama, and dance) | 15 sessions over five weeks | Group. Face to Face | Locally identified non-specialized facilitators | NR |

| Unterhitzenberger and Rosner [74] | Unstructured Emotional Writing (23) |

Positive writing (23), No Writing (23) |

Emotional Writing involved participants writing about their deepest emotions concerning their loss. Positive Writing participants were asked to write about a trivial but positive topic like their favourite hobbies | 30 min weekly for three weeks | Individual. Face to Face | School Teachers | Adolescents received instructions and wrote in their mother tongue, Kinyarwanda |

NA Not applicable, NR Not reported

CBT-based interventions

All but two CBT-based studies tested manualized interventions delivered in group face-to-face format. One delivered CBT in an individual format [70] while the other was an online guided self-help intervention [62]. The two group Trauma-Focused CBT (TF-CBT) also included a few individual sessions for trauma narration to “prevent vicarious traumatization” [67, 68]. The different manuals used across studies included core CBT elements like psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, activity scheduling, problem-solving, and relaxation techniques, as shown in Table 4. The manual used by Are et al. [55] was developed in Nigeria by one of the co-authors and used in two other Nigerian studies [56, 61]. This is in contrast with other studies which used manuals developed in Western countries. Two interventions added other elements to CBT. The Guided Internet Assisted Intervention (GIAI) combined CBT techniques with interactive peer support [62], while another study [72] added creative expressive elements to CBT.

In terms of intensity, all the interventions can be considered Low-intensity as they were either delivered in high volume (group format) and/or by non-mental health professionals, or as self-help. However, they varied in duration, with seven interventions lasting 5 weeks or less and six lasting 8 weeks or more (Table 4). Although some interventions lasted 5 weeks, they had multiple sessions per week (15 sessions overall) in contrast with others, which had one session per week (five sessions). Eight interventions were delivered by mental health professionals, while two were delivered by non-professionals (e.g., teachers and lay healthworkers). In the guided self-help, guidance was provided by therapists [62].

Interpersonal psychotherapy

Like most CBT-based studies, the two IPT studies were manualized interventions delivered in group face-to-face format. One intervention was delivered to Ugandan adolescents displaced by war [75] while the other was for HIV orphaned adolescents in South Africa [69]. In both studies, 1.5-2 hr weekly sessions were delivered by lay facilitators for 16 weeks, using the same IPT manual developed by a humanitarian organization. Though one study [75] randomized participants to intervention (IPT), and two control groups (Creative Play and Waitlist), they only analyzed the IPT group against the waitlist group.

Other intervention types: wise interventions and creative psychological interventions

Wise Interventions are a novel class of ordinary, briefer, and precise positive psychological interventions aimed at altering a specific way in which people think or feel [76]. The WIs (Shamiri) are the first positive psychology intervention to combine three WIs (Growth Mindset, Value Affirmation, and Gratitude). Shamiri means “thrive” in Kiswahili, which reflects the intervention’s focus on positive psychology rather than mental illness [64, 65]. The two WIs were conducted among low-income students in an urban slum in Kenya. One intervention [64] was delivered in a group format over 4 weeks by former high school graduates, while the other (Shamiri Digital) [65] was a single-session digital self-help intervention.

Three studies examined the effect of Creative Psychological Interventions on depressive symptoms. CPIs encompass a variety of psychotherapautic techniques that utilize creative and expressive forms of communication and expression to address psychological and emotional issues [77]. Two of these studies tested Expressive Writing. Writing for Recovery (WFR) [63] adopted a structured testimonial/narrative approach in communicating an emotional experience to normalize distressing reactions while Emotional Writing was an unstructured writing intervention for HIV-orphaned adolescents and involved participants writing about their deepest emotions concerning their loss [74]. The other CPI was conducted among high school students and employed art-based psychotherapeutic approaches to facilitate psychological change [66].

Cultural/contextual adaptation

As shown in Table 4, sixteen studies reported some form of adaptation to suit the local culture and context, while six did not. The most common form of adaptation was the delivery of the intervention in the local language. This involved group discussions in the local language and/or translation of the screening instrument and manual. Three studies [67, 68, 75] used locally developed screening instruments and three used locally developed manuals [55, 56, 61]. Eseadi et al. adapted the intervention manual to incoporate the religious philosophies and traditions of the participants. Another common adaptation was the use of local metaphors, and culturally applicable analogies and exemplars. The two Trauma-Focused CBT in the DRC also used cultural games and songs [67, 68]. Are et al. encouraged the use of helpful cultural and religious coping mechanisms while Osborn et al. encouraged the use of local arts, languages and traditions [55, 66]. Three interventions ensured rigorous cultural appropriateness by involving community stakeholders in the development and implementation of the interventions [63–65].

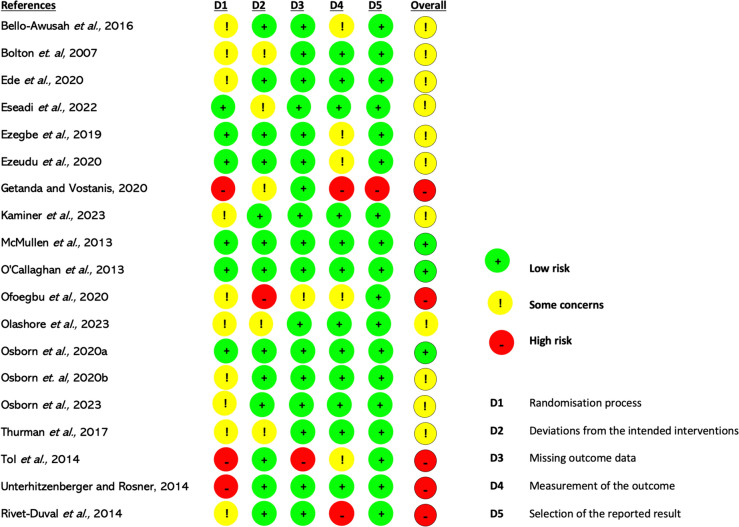

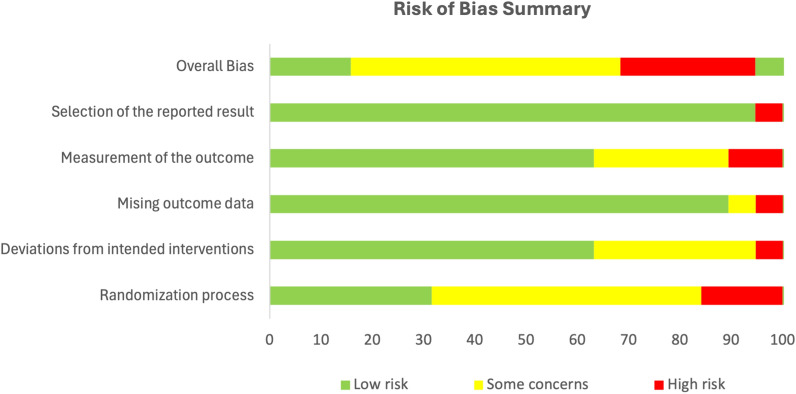

Risk of bias assessment

Eleven of the ninteen RCTs were judged as having “some concerns”. Five studies were judged high risk, while three had a low RoB (Fig. 3). Bias arose mainly from the ‘Randomization Process’ and ‘Measurement of the Outcome’ domains (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias judgment for included RCTs

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary graph

Figure 3 presents the RoB for each RCT. In the Randomization Process, studies were judged high or had “some concerns” due to lack of information on allocation concealment [62, 64, 66, 69–73] and/or significant differences in prognostic variables between intervention and control groups [72, 74]. For instance, in one study, participants differed significantly in baseline depressive symptoms, social support, and experience of traumatic events [72]. In the Measurement of the Outcome domain, five studies [56, 59, 60, 62, 72] were judged to have “some concerns” due to unblinded outcome assessors. Two studies [63, 73] were rated high because unblinded intervention facilitators supervised the post-intervention completion of screening instruments, making outcome assessment more likely to be influenced by knowledge of allocation. For Deviation from Intended Intervention, one study [62] was rated high because it neither reported information on intervention fidelity nor whether participants were analyzed in the groups they were randomized to (e.g. using Intention-To-Treat(ITT) analysis). Furthermore, 41% of participants dropped out and were excluded from the outcome analysis. Five studies had “Some Concerns” due to lack of information on intervention fidelity and or analysis methods [58, 63, 73] or reported protocol deviations [69, 75]. In the Missing Outcome Data domain, most studies had low RoB. However, one study [67] was rated high due to potential outcome-related missing data. One study [61] had “some concerns” due to lack of missingness accounting and sensitivity analysis. Only one study [63] was judged as having a high RoB in the Selection of Reported Results Domain because it used multiple methods to assess treatment effects but reported only one set of results. For the Non-randomized studies, the two pre-post intervention studies [54, 61] had serious RoB while the controlled trial [55] had a low RoB (Table 5).

Table 5.

Risk of Bias Judgement for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (NRSI)

| References | Confounding | Selection of participants | Deviation from intervention | Missing data | Measurement of outcome | Selective reporting | Overall judgment | Reasons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adegbolagun et al. [54] | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Serious | Possible confounding factors such as age and gender not adjusted for. Regression to the mean not accounted for. Self-reported measures used |

| Are et al. [55] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Use of control group largely eliminated confounding bias |

| Isa et al. [61] | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Serious | Possible confounding factors like age, gender, education, SES, not measured and controlled for. Also does not use appropriate statistical methods to account for regression to the mean. Self-reported outcome could lead to response bias |

Effect of psychosocial interventions

Table 6 shows the results of each study, including baseline and post-intervention mean depression scores, treatment effect and factors affecting efficacy. Overall, 19 studies, of which 12 were CBT-based, reported statistically significant reductions in depressive symptoms in the intervention compared to control groups. Although the follow-up durations varied between studies, majority of the CBT interventions (nine) maintained their effects at follow-up. Although both IPT interventions were similar (same manual, duration, and delivery personnel), results were mixed. Bolton et al. [75] reported a significant decrease from baseline depressive symptoms (P = 0.02) only amongst girls, while Thurman et al. [69] revealed no significant decrease (P = 0.145). Despite the differences in their delivery formats, both Wise Interventions reported significant decreases from baseline mean depression scores in intervention groups compared to control [64, 65]. Interestingly, the single-session digital version (Shamiri Digital) [65] showed a more significant reduction and larger effect size (P = 0.028, Cohen’s d = 0.5) than the four-session group face-to-face version (Shamiri Group)(64) (P = 0.038, d = 0.32). Two of the three creative psychological interventions showed significant effects. “Pre-Texts”, the arts-based therapy showed a significant reduction in depression scores (P = 0.001, d = 0.52). The structured writing intervention, Writing for Recovery (WFR) [63] resulted in a significant decrease in depressive symptoms (P = 0.0001) with a large effect size (np2 = 0.338). In contrast, the unstructured writing intervention showed no significant change from baseline (P = 0.518) [74]. The two other interventions had small effect sizes. The universal preventive intervention, Resourceful Adolescent Programme (RAP) [73], resulted in a significant decrease from baseline depressive symptoms (P < 0.001), with a small effect size (d = 0.32). However, the effects were not maintained at 6-months follow-up. The intervention which combined psychoeducation and problem-solving also yielded a small effect (ƞp2 = 0.20, p = 0.001). Overall, both culturally adapted and non-adapted interventions showed positive effects.

Table 6.

Results

| References | Intervention group mean depression scores (Standard Deviation) | Control group mean depression scores (Standard Deviation) | Treatment effect (P value) | Effect size | Factors affecting efficacy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-intervention | Baseline | Post-Intervention | ||||

| Adegbolagun et al. [54] | 4.50 (2.81) | 2.83 (1.92) | NA | NA | P < 0.02 | NA | Increase in coping as a possible mediator |

| Are et al. [55] | 24.30 (6.59) | 4.60 (7.35) | 24.25 (6.06) | 17.05 (11.17) | P = 0.0001 | np2 = 0.32 | Age, gender, religion, and parent’s level of education did not predict outcome. Increased self esteem and knowledge of depression as possible mediators |

| Bella-Awusah et al. [56] | 25.3 (8.8) | 11.8 (9.5) | 24.2 (6.1) | 21.1 (7.9) | P = 0.0001 | ƞp2 = 0.31 | NR |

| Bolton et al. [75] | 43.5 (10.1) | 27.8 (17.2) | 44.2 (10.8) | 37.3 (15.8) | P = 0.02 | NR | Sex predicted the outcome. Age did not predict outcome. Increased adherence was associated with reduction in symptoms |

| Ede et al. [57] | 49.10 (6.25) | 12.45 (6.61) | 50.44 (7.68) | 49.30 (4.99) | P < 0.001 | ƞp2 = 0.88 | NR |

| Eseadi et al. [58] | 40.15 (4.24) | 12.91 (5.70) | 41.97 (4.92) | 44.39 (5.56) | P < 0.0001 | ƞp2 = 0.82 | NR |

| Ezegbe et al. [59] | 68.57 (10.06) | 14.68 (1.63) | 65.11 (13.06) | 64.63 (17.13) | P = 0.0001 | ƞp2 = 0.91 | Level of adherence did not moderate treatment outcome |

| Ezeudu et al. [60] | 46 (6) | 24 (4) | 43 (5) | 42(4) | P < 0.001 | ƞp2 = 0.916 | NR |

| Getanda and Vostanis [63] | 18.1 (6.7) | 10 (6.9) | 15.8 (5.3) | 17.0 (5.5) | P = 0.0001 | np2 = 0.338 | NR |

| Isa et al. [61] | 24.4 (11.18) | 3.94 (2.10) | NA | NA | P = 0.001 | NA | Increased Hope and knowledge of depression as a possible mediator |

| Kaminer et al. [70] | 26.97 (14.96) | 15.44 (14.16) | 26.79 (13.27) | 23.44 (17) | P = 0.03 | d = 0.51 | NR |

| McMullen et al. [67] | 38.1 (9.3) | 7.0 (5.8) | 38.1 (11.1) | 29.3 (13.6) | P < 0.001 | ƞp2 = 0.567 | NR |

| O'Callaghan et al. [68] | 37.96 (10.16) | 13.96 (10.30) | 39.18 (10.57) | 40.04 (15.18) | P < 0.001 | ƞp2 = 0.517 | NR |

| Ofoegbu et al. [62] | 65.30 (2.61) | 8.60 (0.21) | 64.78 (3.67) | 65.50 (2.4) | P = 0.0001 | ƞp2 = 0.959 | NR |

| Olashore et al. [71] | 13 (2.0) | 7 (3.0) | 13 (3.0) | 9 (2.0) | P = 0.001 | ƞp2 = 0.20 | NR |

| Osborn et al. [65] | 14.43 (3.35) | 8.46 (4.98) | 13.18 (2.89) | 10.64 (4.89) | P = 0.028 | d = 0.5 | Younger adolescents reported larger declines in depressive symptoms. Adolescents with moderate to severe depression had larger symptom reduction |

| Osborn et al. [64] | 13.43 (4.14) | 10.21 (4.39) | 12.91 (3.52) | 12.52 (4.23) | P = 0.038 | d = 0.32 | Age and sex were not associated with outcome |

| Osborn et al. [66] | 8.29 (5.30) | 5.69 (4.23) | 8.40 (4.69) | 8.37 (5.53) | P = 0.001 | d = 0.52 | NR |

| Rivet-Duval et al. [73] | 51.8 (9.07) | 47.5 (7.95) | 50.61 (9.19) | 49.98 (11.07) | P < 0.001 | d = 0.32 | NR |

| Thurman et al. [69] | 16.03 (1.39) | 16.46 (1.92) | 14.67(1.26) | 15.63 (2.12) | P = 0.145 | NE | Age and sex showed no moderation effect on results |

| Tol et al. [72] | 9.97 (4.82) | 8.15(5.02) | 11.28 (5.08) | 8.49 (5.8) | P = 0.149 | NE | Larger households and having both parents were effect moderators |

| Unterhitzenberger and Rosner [74] | 18.8 (10.60) | 20.6 (11.4) | 15.7 (9.9) | 12.1 (10.3) | P = 0.518 | NE | NR |

NA Not applicable, NR Not reported, NE No effect

Measures of effect: np2, Partial Eta Squared, d Cohen’s D

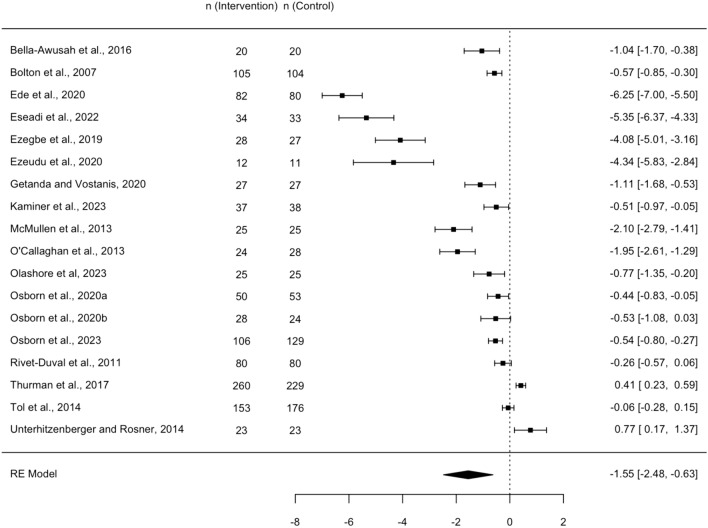

Meta-analysis

The meta-analysis incorporated data from 18 RCTs involving 2338 participants. One study, identified as an extreme outlier due its exceptionally large effect size (Hedges’ g = −33) and high risk of bias was excluded from the analysis [62]. The random effects model revealed a significantly large effect of psychosocial interventions compared to the control groups (Hedges’ g = −1.55, 95% CI −2.48, −0.63). Figure 4 presents the forest plot, displaying the effect sizes (Hedges’ g) for each study, the pooled effect size and 95% confidence intervals. Negative effect sizes indicate a more favorable outcome (symptom reduction) for the psychosocial intervention groups relative to the control groups. The analysis revealed high heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 98.8%, Q = 574, p < 0.0001), indicating significant variability. Sensitivity analyses, excluding studies with a high risk of bias amplified the effect size (Hedges’ g = −1.96, 95% CI −3.5 to −0.86), although the heterogeneity remained unchanged. However, removing the four outliers whose effect sizes were much larger than the others (g > 4) resulted in a reducted effect size (g = −0.59, 95% CI −0.98, −0.2) and decreased heterogeneity (I2 = 93.8%). Interestingly, these outliers were the group CBT interventions with the longest duration (12 weeks) and were all conducted among undergraduate students in Nigeria [57–60]

Fig. 4.

Forest plot – effects of Psychosocial Interventions of depressive symptoms. Negative effect sizes signify a more favorable outcome (symptom reduction) for the psychosocial intervention groups relative to the control groups

Subgroup analysis, depicted in Fig. 5, indicated significant differences in effect size by intervention type (Test for subgroup differences: p = 0.027). CBT-based interventions represented in nine studies, had the strongest effect (Hedges’ g = −2.84, 95% CI −4.29; −1.38), albeit with high within-group heterogeneity (I2 = 99.7%). Other subgroups, with fewer studies, exhibited smaller average effects. Wise Interventions had a moderate effect (g = −0.46, 95% CI −0.53, −0.39) while Interpersonal Psychotherapy (g = −0.08, 95% CI −1.05, 0.88) and Creative Psychological Interventions (g = −0.29, 95% CI −1.38, 0.79) showed small non-significant effects. Within-group heterogeneity was high for IPT and CPI (99.9% and 99%, respectively), while WI showed no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot for sub-group analysis

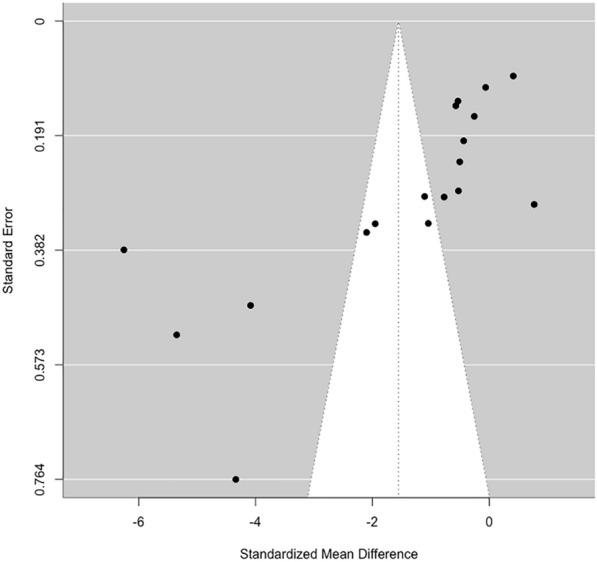

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger’s test, which indicated significant funnel plot asymmetry (p < 0.0001), raising concerns about potential publication or small study bias (Fig. 6). However, Duval & Tweedie’s trim and fill analysis estimated no missing studies. The pooled effect size was maintained after the small-study bias adjustment, suggesting the robustness of the findings [78].

Fig. 6.

Funnel plot for assessing publication bias. The observed funnel plot asymmetry should be interpreted cautiously, considering the high heterogeneity among the included studies

Factors affecting intervention efficacy: predictors, moderators and mediators

As shown in Table 5, majority of studies neither assessed potential predictors nor conducted moderator and mediation analysis. Three studies conducted statistical analysis to determine what baseline variables would predict outcomes [55, 64, 75]. Gender predicted the outcome in one study [75], as the intervention was only effective for girls, but it was not an outcome predictor in the others [55, 64]. Age did not predict outcome in any of the three studies.

Age moderated the efficacy of Shamiri Digital [65], as younger adolescents reported a larger decline in depressive symptoms. Contrastingly, neither age nor gender were moderators in the study by Thurman et al. [69]. Results for level of adherence as a moderator were also mixed, as increased adherence was associated with symptom reduction in one study [75] but not in another [59]. The severity of depression was an effect moderator in Shamiri Digital as there was better response among adolescents with moderate-to-severe depression scores [65].

Increase in coping, self-esteem, hope, and knowledge of depression were identified as possible mediators [54, 55, 61].

Discussion

This systematic review is the first to assess the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for depression among young people in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The meta-analysis showed that these interventions, particularly CBT, significantly reduce depressive symptoms, although substantial heterogeneity necessitates cautious interpretation of pooled estimates. Subgroup analysis indicated significant variation in efficacy by intervention type. CBT was shown to be the most effective intervention, corroborating findings from systematic reviews in other contexts [21, 38]. Wise Interventions (WI) showed moderate effects, while IPT and CPI had small effects. However, limited number of studies per group may affect the reliability of the subgroup estimates. The WIs particularly the single session intervention (SSI) had effect sizes comparable to some well-established psychological treatments, which is interesting because WIs were not originally developed for depression [65, 76]. A similar study in the US found a digital single-session WI to be moderately effective in reducing adolescent depressive symptoms [79]. As positive psychology interventions, WIs could help address stigma, which is a major barrier to treatment in SSA. However, more studies are needed to ascertain the durability and reproducibility of their effects. A review by Weersing et al. [38] found IPT to be effective among young people but less so in group format, which could explain the lower efficacy of Group-IPT compared to Group CBT in our review. Furthermore, the effective Group-IPT studies from their review were conducted among the general population, as opposed to war-affected adolescents in this review. In contrast, Group TF-CBT studies showed large effects, suggesting that they might be better suited than IPT for trauma-affected adolescents in SSA.

Exploring sources of heterogeneity

While the sensitivity analysis and publication bias adjustment suggest robust findings, the high overall and subgroup heterogeneity necessitate cautious interpretation of pooled effect sizes. Thus, it might be more informative to focus on understanding the sources of variation across studies rather than relying solely on the pooled estimate. Subgroup analysis revealed high within-group heterogeneity for all subgroups except WI, indicating that variability extends beyond intervention types. Differences in study population and design, and intervention delivery may contribute to this variability. For instance, within CBT studies, heterogeneity likely arises from differences in participant characteristics, and intervention delivery methods. Studies with homogenous characteristics and delivery modalities, such as the culturally adapted group trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT) for war-affected adolescents in DRC [67, 68], showed consistent effect sizes (g = −2.10, −1.95). In contrast, the individual TF-CBT for South African adolescents with moderate and severe PTSD had a smaller effect size (g = −0.51). The comparatively smaller effect size is attributable to the study’s inclusion of more clinically severe cases and its use of a treatment-as-usual control compared to the non-clinical population and waitlist control in the DRC studies. The group CBT intervention delivered to war-affected secondary school students in Burundi exhibited a much lower effect size (g = −0.06) than the other studies involving trauma-affected youths, likely due to its non-trauma-focused approach [72].

The other CBT interventions targeted general populations of high school and undergraduate students and also exhibited varying effects likely due to dissimilar population, inclusion criteria and intervention duration. For example, the extensive group CBT studies (12 week duration) delivered to a general population of undergraduate students in Southeast Nigeria [57–60] yielded much larger effect sizes (g =−4.08 to −6.25) compared to the shorter interventions (5 weeks) delivered to clinical populations of secondary school students in Southwest Nigeria (g = −1.04, −1.26) [55, 56].

The two group IPT trials showed disparate effects potentially due to differences in cultural adaptation and trauma exposure. Culturally adapted IPT for war-displaced adolescents had a moderate effect size [75] while non-adapted IPT delivered to HIV-orphaned adolescents showed no effect [69]. The CPI subgroup also had significant heterogeneity, possibly stemming from variations in participant and intervention characteristics. For instance, the structured EW intervention was effective for displaced secondary school students in Kenya [63], while unstructured EW showed no effect for orphaned adolescents in Rwanda [74]. Further studies are needed to ascertain the efficacy of EW as an intervention for depression and whether structured EW is more effective than unstructured. Unlike other subgroups, WIs showed no heterogeneity, likely because both studies were conducted by the same authors with similar participants and settings.

Durability of effect and factors affecting efficacy

The intervention effects were generally maintained at follow-up, but many studies had short or no follow-up periods. Considering the high relapse and recurrence rates among adolescents [83], future research is needed to determine the durability of effects [80]. Additional studies are also required to uncover factors influencing intervention efficacy. While age, gender and adherence level were assessed in few studies, their predictive or moderating roles varied. A systematic review had similarly mixed findings on predictors and moderators of efficacy [38]. This gap is a key area of focus for future research as identifying these factors can lead to the development of tailored interventions. The role adaptation plays in efficacy is also worth exploring. Generally, evidence from this review is mixed as with other reviews. In their review, Cuijpers et al. did not find any indication that a specific contextual adaptation was associated with better outcomes [47]. Contrarily, another systematic review found culturally adapted interventions more effective than non-adapted ones but it was unclear what specific adaptations were important [81]. Since cultural adaptation can increase acceptability and adherence which are both associated with increased effectiveness [82], future studies should examine what adaptations are beneficial in different SSA countries.

Intervention delivery modalities

All the interventions can be classified as Low-Intensity Psychological Interventions (LIPIs) due to reduced usage of therapist’s time (fewer sessions and/or high-volume delivery in group format), delivery by non-professionals, or as digital self-help interventions [83]. Compared to HICs and LMICs, this review found more interventions delivered in group format [21, 38]. Though group interventions are resource-effective hence better-suited for SSA, they are not suitable for everyone. For example, people with social phobia, interpersonal problems, recent traumatic events, and actively suicidal patients might be better served by individual therapy [84]. More studies are required to determine which people are better served by group vs individual interventions. Innovative approaches like embedding individual sessions in group interventions as done in the TFT-CBT studies [67, 68] can be further explored as they could prove more cost-effective. Interventions delivered by both mental health professionals and non-professionals were found to be effective. This concurs with a systematic review which found psychosocial interventions delivered by lay facilitators to be effective [85]. This finding is important for mental health policy in SSA as the region has the lowest ratio of mental health workers per population in the world [22]. Other novel innovative LIPIs were digital self-help and single session interventions (SSIs). Both self-help Digital Mental Health Interventions (DMHI) proved effective despite different durations (10-weeks vs single-session) and approaches (CBT-based vs WI/positive psychology). The evidence base for DMHI is growing and reviews in other contexts have found DMHI like computerized CBT to be effective in reducing adolescent depression [86]. An added advantage of digital SSIs is their ability to circumvent the high attrition often seen in multisession interventions [65]. Digital self-help interventions represent an opportunity to increase treatment access to young people in SSA due to increasing access to digital technology [87]. DMHI are also resource-effective and can help combat stigma thus warrant further exploration in the region.

Limitations

The high heterogeneity observed in this study introduces challenges to the certainty and generalizability of the pooled effect size estimate. This variability among included studies suggests that combining their effect sizes may not be ideal, as they might measure different effect sizes based on study population. However, interventions between studies varied substantially (e.g., content, frequency, duration, adaptation and delivery personnel), suggesting that high heterogeneity may be inevitable.

Publication bias remains possible even though no missing studies were estimated. Notably, the lack of change in effect size after adjustment raises the possibility that funnel plot asymmetry may be attributable to between-study heterogeneity rather than small-study bias. Funnel plots, by assuming that the dispersion of effect sizes is due to sampling error, do not control for the fact that studies may be estimators of different true effects, further underscoring the importance of interpreting the pooled effect size in light of heterogeneity [50].

Another important limitation is the inability to assess the durability of effects due to inconsistent reporting of follow-up time across included studies.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence supporting the efficacy of psychosocial interventions, particularly CBT, in alleviating depressive symptoms among young people in SSA. However, the observed heterogeneity highlights the importance of considering intervention types, delivery modalities, participant populations and factors affecting efficacy. Thus, while psychosocial interventions show promise in reducing youth depressive symptoms in SSA populations, further research to identify components that work best for specific subgroups is imperative. Tailored interventions for specific populations may be more effective than a one-size-fits-all approach.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1. Prisma checklist.

Supplementary material 2. Systematic review protocol.

Supplementary material 3. Search strategy.

Supplementary material 4. Reasons for exclusion.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- APAI

Acholi psychosocial assessment instrument

- AYPAI

African youth psychosocial assessment instrument

- BDI

Beck’s depression inventory

- CBT

Cognitive behavioural therapy

- CMD

Common mental disorders

- CCT

Controlled clinical trial

- CPI

Creative psychological interventions

- DMHI(s)

Digital Mental Health Intervention(s)

- DRC

Democratic Republic of Congo

- EW

Expressive writing

- g

Hedge’s g

- GBD

Global burden of disease

- GIAI

Guided internet assisted intervention

- HICs

High Income Countries

- IPT

Interpersonal psychotherapy/psychotherapy

- ITT

Intention to treat

- LMICs

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- LIPI

Low intensity psychological interventions

- ƞp2

Partial Eta squared

- NRSI

Non-randomized studies of interventions

- PICOS

Population, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- RAP

Resourceful adolescent programme

- RCT

Randomized control trial

- RoB

Risk of bias

- SA

South Africa(n)

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- SSI

Single session intervention

- TF-CBT

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy

- WFR

Writing for recovery

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WI

Wise intervention

Author contributions

LO was responsible for the conceptualization, design, writing, and editing of the study and manuscript. EU contributed to the conception of the study, writing and revision of the manuscript. AA contributed to the study design and revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding or grant from any agency or institution in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression. Accessed 4 Jul 2022.

- 2.GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137–50. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chand SP, Arif H. Depression. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430847/. Accessed 8 Jan 2023.

- 4.Depression and other common mental disorders: Global Health Estimates. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf;jsessionid=DC78EFEF12D188280E6C4CE5D261FDDA?sequence=1. Accessed 4 Jul 2022.

- 5.World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 17 Jul 2022.

- 6.Gbadamosi IT, Henneh IT, Aluko OM, Yawson EO, Fokoua AR, Koomson A, et al. Depression in Sub-Saharan Africa. IBRO Neurosci Rep. 2022;1(12):309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ibneur.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):878–889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel V, Maj M, Flisher AJ, Silva MJD, Koschorke M, Prince M, et al. Reducing the treatment gap for mental disorders: a WPA survey. World Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):169. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoder HNC, Tol WA, Reis R, de Jong JTVM. Child mental health in Sierra Leone: a survey and exploratory qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10:48. doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0080-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, Rasmussen B, Smit F, Cuijpers P, et al. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(5):415–424. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations. Definition of Youth. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf. Accessed 13 Jul 2022.

- 12.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beirão D, Monte H, Amaral M, Longras A, Matos C, Villas-Boas F. Depression in adolescence: a review. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2020;27(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s43045-020-00050-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blakemore SJ. The social brain in adolescence. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(4):267–277. doi: 10.1038/nrn2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patton GC, Viner R. Pubertal transitions in health. The Lancet. 2007;369(9567):1130–1139. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–1150. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daly M. Prevalence of depression among adolescents in the U.S. From 2009 to 2019: analysis of trends by sex, race/ethnicity, and income. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(3):496–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patalay P, Gage SH. Changes in millennial adolescent mental health and health-related behaviours over 10 years: a population cohort comparison study. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(5):1650–1664. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJL, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santomauro DF, Herrera AMM, Shadid J, Zheng P, Ashbaugh C, Pigott DM, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davaasambuu S, Hauwadhanasuk T, Matsuo H, Szatmari P. Effects of interventions to reduce adolescent depression in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;1(123):201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240049338. Accessed 14 Jul 2022.

- 23.Pozuelo JR, Desborough L, Stein A, Cipriani A. Systematic review and meta-analysis: depressive symptoms and risky behaviors among adolescents in low- and middle-income countries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61(2):255–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayborne ZM, Varin M, Colman I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stelmach R, Kocher EL, Kataria I, Jackson-Morris AM, Saxena S, Nugent R. The global return on investment from preventing and treating adolescent mental disorders and suicide: a modelling study. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(6):e007759. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Youth Development | African Union. https://au.int/en/youth-development. Accessed 16 Jul 2022.

- 27.Cortina MA, Sodha A, Fazel M, Ramchandani PG. Prevalence of child mental health problems in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(3):276–281. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jörns-Presentati A, Napp AK, Dessauvagie AS, Stein DJ, Jonker D, Breet E, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in sub-Saharan adolescents: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0251689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. Mental Health ATLAS 2017. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241514019. Accessed 16 Jul 2022.

- 30.Psychosocial Interventions for Mental and Substance Use Disorders: A Framework for Establishing Evidence-Based Standards. https://www.nap.edu/read/19013/chapter/3. Accessed 16 Jul 2022. [PubMed]