Abstract

Background

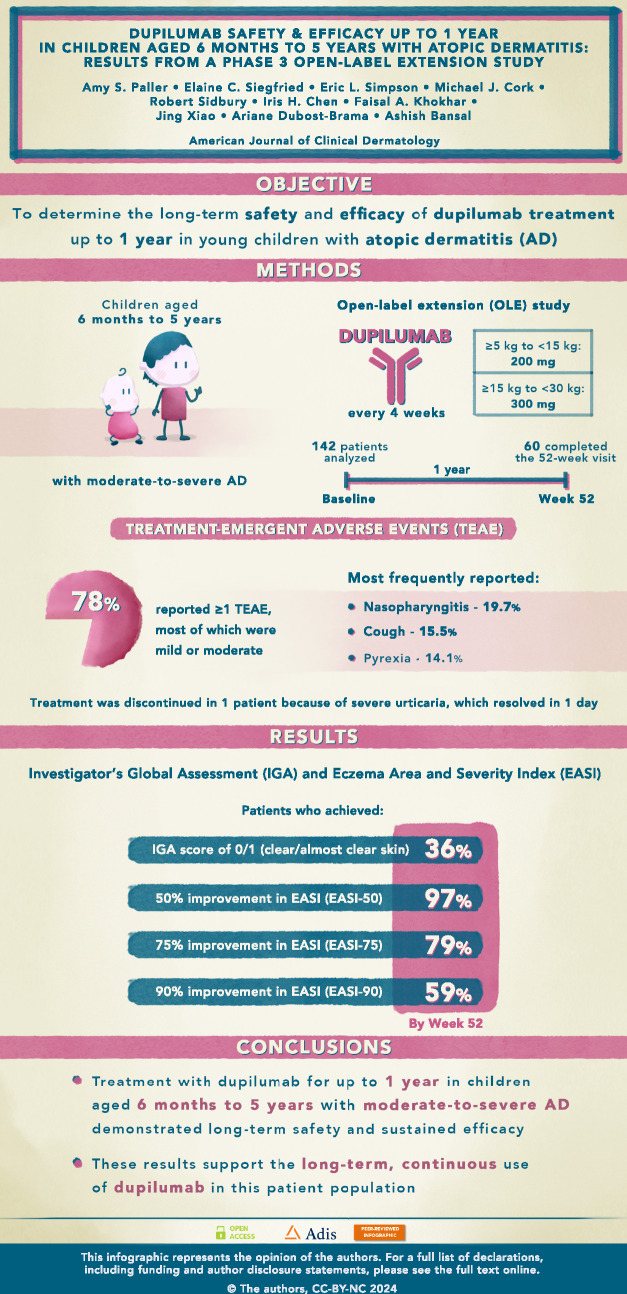

Pediatric patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) often experience a high disease burden and have a high risk of persistent disease. Standard-of-care immunosuppressive systemic treatments have been used off-label for AD in pediatric patients despite concerns for suboptimal safety with continuous use and risk of relapse upon discontinuation. The biologic agent dupilumab is the first systemic treatment approved for moderate-to-severe AD in children as young as 6 months. Long-term safety and efficacy data in this patient population are needed to inform continuous AD management.

Objectives

The purpose of this work was to determine the long-term safety and efficacy of dupilumab treatment up to 1 year in an open-label extension (OLE) study [LIBERTY AD PED-OLE (NCT02612454)] in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD who previously participated in the 16-week, double-blind, phase 3 LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL trial (NCT03346434 part B; parent study) and were subsequently enrolled in PED-OLE.

Methods

In PED-OLE, patients received dupilumab every 4 weeks according to a weight-tiered regimen (body weight ≥ 5 kg to < 15 kg: 200 mg; ≥ 15 kg to < 30 kg: 300 mg).

Results

Data for 142 patients were analyzed, 60 of whom had completed the 52-week visit at time of database lock. Mean age at baseline was 4.1 y [SD, 1.13; range, 1.0–5.9 years]. A majority (78.2%) of patients reported ≥ 1 treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE), most of which were mild or moderate and transient. The most frequently reported TEAEs were nasopharyngitis (19.7%), cough (15.5%), and pyrexia (14.1%). One TEAE led to treatment discontinuation (severe urticaria, which resolved in 1 day). By week 52, 36.2% of patients had achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0/1 (clear/almost clear skin), and 96.6%, 79.3%, and 58.6% had at least 50%, 75%, or 90% improvement, respectively, in Eczema Area and Severity Index scores.

Conclusions

Consistent with results seen in adults, adolescents, and older children (aged 6–11 years), treatment with dupilumab for up to 1 year in children aged 6 months to 5 years with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe AD demonstrated an acceptable long-term safety profile and sustained efficacy. These results support the long-term continuous use of dupilumab in this patient population.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT02612454 and NCT03346434 (part B).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40257-024-00859-y.

Plain language summary

Plain Language Summary

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that often results in a high disease burden in young children and their families. Patients often need long-term treatment to control their disease symptoms, including itch and rash. Dupilumab treatment for 16 weeks has shown benefits in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD, with an acceptable safety profile. As AD is likely to continue from childhood into adolescence and adulthood, there is a need for data supporting long-term use of dupilumab in young children. In this study, children who completed the 16-week study continued dupilumab treatment for up to 1 year, receiving 200 mg or 300 mg of dupilumab (depending on the child’s bodyweight) every 4 weeks. Through the year of treatment, 78.2% of patients reported at least one side effect, most of which were mild or moderate. Only one patient interrupted treatment because of severe skin rash (hives), which was resolved in 1 day. At the end of the year, 36.2% of patients had clear or almost clear skin, and almost all (96.6%) achieved at least 50% improvement in their extent and severity of disease. Additionally, 79.3%, and 58.6% had at least 75% or 90% improvement in their extent and severity of disease. In summary, consistent with results seen in adults, adolescents, and older children, this study showed that 1-year dupilumab treatment provides continued benefits with an acceptable safety profile. These results support long-term continuous use of dupilumab in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD.

Graphical Abstract

Video abstract

What is the long-term safety and efficacy profile in young children with moderate-to-severeatopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab?

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40257-024-00859-y.

| Digital Features for this article can be found at 10.6084/m9.figshare.25476070 |

Key Points

| For young children aged ≥ 6 months with atopic dermatitis (AD) inadequately controlled with topical therapies, 16 weeks of treatment with dupilumab has proven efficacious, with an acceptable safety profile. Many of these children experience persistent disease into adolescence and adulthood; therefore, long-term safety and efficacy data are important to inform continuous disease management. |

| This was an analysis of data from a long-term open-label extension study in children aged 6 months to 5 years with uncontrolled AD. Data presented here demonstrate that dupilumab treatment every 4 weeks, for up to 52 weeks, had an acceptable safety profile. |

| Dupilumab provided sustained clinical benefits in reducing AD clinical signs and symptoms, as well as improvements in the health-related quality of life of patients. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin disease in childhood [1], with reported prevalence around the world ranging from 3% to 40% in children aged < 6 years [2–4]. Approximately 50% of patients with AD develop symptoms within their first year of life, with onset below 5 years of age in up to 95% of cases [5]. AD has a chronic relapsing course [5] and commonly precedes development of other atopic conditions such as food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma [6, 7].

Moderate-to-severe AD is characterized clinically by flares featuring eczematous skin changes and intense itch and increased susceptibility to recurrent skin infections. The pathophysiology of the condition is related to the presence of a defective skin barrier, as well as both local and systemic type 2 immune skewing [8]. The main symptom of AD is pruritus [9], which often results in significant sleep disruption, irritability, and stress for the patient’s family members [10]. AD has been associated with a markedly impaired patient and family quality of life, similar to or greater than that seen in other chronic skin and extracutaneous diseases, including diabetes, asthma, and sickle cell disease [11, 12]. More than half of children with severe AD have moderate-to-high impairments in their quality of life [13]. Parents of children with AD experience sleep loss, and may experience depression, anxiety, and helplessness due to the stress caused by their child’s disease [14].

Children with moderate-to-severe AD often have a family history of atopy, an increased risk of developing other atopic conditions, and a higher risk of persistent skin disease into adolescence and adulthood [15, 16].

Data from the real-world PEDISTAD registry of children with AD inadequately controlled by topical therapies revealed that only 22.3% of children aged 2 to < 6 years and 11.7% of children aged 0 to < 2 years were receiving systemic medications for AD [17], despite a significant disease burden among the patients and their families. These findings reveal an unmet need for effective and well-tolerated therapeutic options for long-term disease control in children aged younger than 6 years with moderate-to-severe AD [17].

Although treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended by published guidelines for children with AD, until recently this class of medication was the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved systemic option for children aged younger than 6 years [18]. Dupilumab is a fully human VelocImmune®-derived [19, 20] monoclonal antibody that blocks the shared receptor component for interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, inhibiting signaling of both IL-4 and IL-13 [21, 22], which are key drivers of type 2-mediated inflammation in multiple diseases [21, 23, 24]. Dupilumab has been approved by the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for patients with type 2 inflammatory diseases, including (since 2017) for adults with moderate-to-severe AD and (since 2022) for children aged 6 years and older with moderate-to severe AD [25, 26]. Results from the 16-week randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL R668-AD-1539 trial (NCT03346434 part B) [27] supported the approval of dupilumab as the first systemic treatment (and only biologic agent available) for children as young as 6 months with moderate-to-severe AD [25, 28].

The objective of this analysis was to evaluate long-term safety and efficacy data for dupilumab in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD who had previously participated in PRESCHOOL part B and who were subsequently enrolled in the open-label LIBERTY AD PED-OLE trial (NCT02612454).

Methods

Study Design

PED-OLE is an ongoing phase 3 open-label extension (OLE) study in patients aged ≥ 6 months to < 18 years with moderate-to-severe AD who had previously participated in a dupilumab AD parent study. This analysis includes patients aged 6 months to 5 years who previously participated in the PRESCHOOL part B study, referred to here as the parent study [27]. The study design and safety and efficacy results of the parent study have been previously reported [27]. Briefly, in PRESCHOOL part B, patients were randomized 1:1 to subcutaneous placebo or a weight-tiered regimen of dupilumab plus low-potency topical corticosteroids (TCS; hydrocortisone acetate 1% cream) for 16 weeks.

PED-OLE had a screening period (day −28 to day −1) from the time patients exited the parent study until they entered the PED-OLE. This was followed by a treatment period that lasted until regulatory approval of the product for the age group of the patient in their geographic region (or 5 years in patients aged 6 months to 11 years, according to Protocol Amendment 4, which was adopted in March 2020) and a 12-week follow-up period. This analysis presents results through week 52 of the PED-OLE, with a data cutoff date of 10 March 2022 for patients who had previously participated in PRESCHOOL part B and were aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD at randomization in PRESCHOOL.

Main Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients included in this analysis were aged 6 months to 5 years at the time of screening, had previously participated in the PRESCHOOL part B [with moderate-to-severe AD at parent study baseline (PSBL)], and had completed ≥ 50% of visits and assessments as defined in the parent study protocol. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria for PRESCHOOL have been previously reported [27]. Patients were excluded from PED-OLE if they experienced a serious adverse event (SAE) during their participation in the parent study that was deemed related to the study drug, or an adverse event (AE) related to the study drug that led to discontinuation from the parent study. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria for PED-OLE can be found in Appendix S1 in the electronic supplementary material (ESM).

Treatment

Patients included in this analysis had received either dupilumab or placebo in the parent study and were started on a weight-tiered regimen of subcutaneous dupilumab upon entering the PED-OLE: patients with body weight ≥ 5 to < 15 kg received 200 mg every 4 weeks (q4w); and those with body weight ≥ 15 kg to < 30 kg received 300 mg q4w.

Basic skin care (including bleach baths), antihistamines, concomitant TCS, and topical calcineurin inhibitors were permitted without restriction, and use of topical crisaborole was permitted if approved locally for treatment of AD. Patients were not permitted to use systemic medications for AD (including corticosteroids and non-steroidal immunosuppressants), except as rescue treatment. Concomitant use of TCS or other AD therapies was not standardized.

Patients who had an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0/1 maintained continuously for a 12-week period beginning at week 40 or later were discontinued from dupilumab (i.e., patients who had an IGA score of 0 or 1 through week 40 to week 52, inclusive, were discontinued from dupilumab at week 52). Disease activity was closely monitored in these patients during the remaining study visits, and treatment with dupilumab was reinitiated in patients who experienced a relapse of disease (IGA score ≥ 2). In these cases, investigators were encouraged to first consider treatment with topical therapy (i.e., medium-potency TCS) and to reinitiate dupilumab only for patients who did not adequately respond after at least 7 days of topical treatment. Such patients were reinitiated directly on their previous dupilumab dose (without a loading dose). These data will be presented in a subsequent manuscript.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of PED-OLE were incidence and rate [patients per 100 patient-years (100PY) and/or events per 100PY] of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) through the last study visit.

Key secondary outcomes were incidence and rate (patients and/or events per 100PY) of treatment-emergent SAEs and incidence and rate (patients and/or events per 100PY) of TEAEs of special interest, [i.e., anaphylactic reactions, conjunctivitis, injection-site reactions, skin infections (excluding herpes viral infections), herpes viral infections, and helminthic infections].

Other secondary outcomes included: proportion of patients with an IGA score of 0/1 (clear/almost clear skin) by visit through week 52; proportion of patients with ≥ 75% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index from baseline of parent study (EASI-75) by visit through week 52; change and percentage change from PSBL in EASI by visit through week 52; change from baseline of parent study in body surface area (BSA) affected by AD by visit through week 52; percentage change from baseline of parent study in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) by visit through week 52; change from baseline of parent study in Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) by visit through week 52, for patients ≥ 4 years of age; and change from baseline of parent study in Infant’s Dermatitis Quality of Life Index (IDQoL) by visit through week 52, for patients < 4 years of age. This analysis also included the additional outcomes of proportion of patients achieving EASI-50/-90 (≥ 50/90% reduction, respectively, in EASI) from baseline of parent study by visit through week 52. Since evaluation of itch requires daily assessment, itch was not included as an outcome to minimize patient burden and ensure the highest possible patient retention in this long-term study.

Analyses

For this study, no formal sample size was estimated, and no power calculations were performed. All clinical safety and efficacy variables were evaluated in the safety analysis set, which consisted of all patients who received one or more doses of dupilumab. All safety data were included from the baseline of the PED-OLE to the database lock. For the evaluation of conjunctivitis, grouped Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Preferred Terms (PTs) consistent with conjunctivitis and selected eye disorder terms were selected for further analysis. A compiled term was used, including all PTs containing the word “conjunctivitis” (conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis allergic, conjunctivitis bacterial, conjunctivitis viral, and atopic keratoconjunctivitis).

All efficacy analyses were descriptive; no formal statistical hypothesis was tested. All observed values, regardless of whether rescue treatment was used or data were collected after withdrawal from study treatment, were used for analysis. No missing values were imputed.

For continuous variables, descriptive statistics included the following: the number of patients reflected in the calculation (n), mean, median, Q1 (25th percentile), Q3 (75th percentile), standard deviation (SD), minimum, and maximum. For categorical or ordinal data, frequencies and percentages are displayed for each category.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

PED-OLE and the parent study, PRESCHOOL part B [27], were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines for good clinical practice and applicable regulatory requirements. Patients (as appropriate, based on the age of the child and country-specific requirements) provided assent, and at least one parent or guardian for each child provided written informed consent. At each study site, the protocol, informed-consent form (ICF), and patient information were approved by an institutional review board and independent ethics committee.

Results

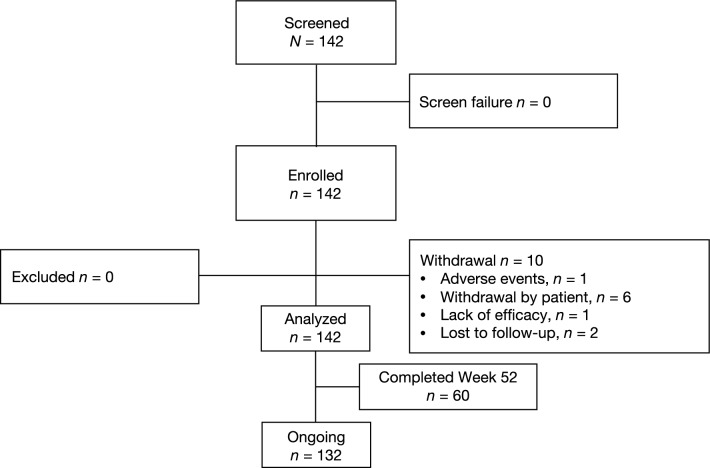

Of the 142 patients screened, all patients met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). At the time of the database lock (10 March 2022), 142 patients from the PRESCHOOL part B trial had been enrolled in PED-OLE and were included in the safety analysis set (39 patients received 200 mg q4w; 103 received 300 mg q4w). Of the 142 patients, at the time of the database lock, 10 patients had withdrawn from the study prematurely, 60 (42.3%) patients had completed the week 52 visit, 132 (93.0%) were ongoing (< 52 weeks), and none had completed the study (planned for at least 5 years). The reasons for premature study discontinuation were withdrawal by the patient (n = 6), patient lost to follow-up (n = 2), adverse events (n = 1), and lack of efficacy (n = 1) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition for patients in PED-OLE who enrolled from PRESCHOOL part Ba. aOnly patients from PRESCHOOL part B were screened in this analysis

Patient Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Mean age of the patients was 4.1 years [SD, 1.13; range, 1.0–5.9 years], and the majority were white (65.5%) and male (62.7%) (Table 1; Table S1 in the ESM). Mean weight and body mass index was 17.5 kg and 16.3 kg/m2, respectively, and 37 (26.1%) patients were overweight (body mass index > 85th percentile for age and sex). Mean duration of AD was 3.7 years, suggesting that most patients had been diagnosed with AD at an early age. A majority of patients had moderate-to-severe disease at PED-OLE baseline, with 42.3% having IGA 3 and 21.1% having IGA 4 (Table 1). Likely reasons for the severity at baseline are the treatment interruption (28-day screening period) between the parent study and the PED-OLE study and the inclusion of patients from the placebo arm of the parent study. All patients had one or more comorbid allergic conditions at baseline, reflecting the high type 2 inflammatory profile in this young patient population. Approximately one-third (35.9%) of patients had received one or more prior systemic immunosuppressive medications for AD besides dupilumab, suggestive of patients with severe disease.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics at baseline of PED-OLE

| All patients (N = 142) |

|

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.1 (1.1) |

| Range, min–max | 1.0–5.9 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 89 (62.7) |

| Country, n (%) | |

| Germany | 2 (1.4) |

| Poland | 34 (23.9) |

| United Kingdom | 8 (5.6) |

| United States | 98 (69.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 93 (65.5) |

| Black or African American | 26 (18.3) |

| Asian | 10 (7.0) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.7) |

| Other | 6 (4.2) |

| Not reported | 6 (4.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 120 (84.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 19 (13.4) |

| Not reported | 3 (2.1) |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 17.5 (3. 9) |

| < 15 kg | 39 (27.5) |

| ≥ 15 kg | 103 (72.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 16.3 (1.8) |

| Overweight, n (%)a | 37 (26.1) |

| Duration of AD, years, mean (SD) | 3.7 (1.2) |

| IGA, n (%) | |

| 0 | 4 (2.8) |

| 1 | 17 (12.0) |

| 2 | 31 (21.8) |

| 3 | 60 (42.3) |

| 4 | 30 (21.1) |

| EASI, mean (SD) | 15.1 (13.2) |

| Percent BSA affected by AD, mean (SD) | 27.8 (20.3) |

| SCORAD, mean (SD) | 43.4 (22.2) |

| CDLQI, mean (SD) | 9.9 (6.9) (n = 85) |

| IDQOL, mean (SD) | 9.7 (7.2) (n = 57) |

| Patients with ongoing or history of allergic/atopic conditions at baseline (excluding AD), n (%) | 142 (100.0) |

| Food allergy | 96 (67.6) |

| Other allergies | 74 (52.1) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 61 (43.0) |

| Hives | 35 (24.6) |

| Asthma | 34 (23.9) |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 8 (5.6) |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 3 (2.1) |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | 2 (1.4) |

| Patients receiving prior systemic medications for AD, n (%) | 51 (35.9) |

| Patients receiving prior systemic corticosteroids | 36 (25.4) |

| Patients receiving prior systemic non-steroidal immunosuppressants | 45 (31.7) |

| Cyclosporine | 17 (12.0) |

| Methotrexate | 12 (8.5) |

| Mycophenolate | 4 (2.8) |

| Azathioprine | 2 (1.4) |

AD atopic dermatitis, BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, IDQOL Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, SD standard deviation, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis

aBMI > 85th percentile for age and sex

Safety Assessment

Safety data for the 142 patients are presented from the baseline of the PED-OLE study up to the database lock. A majority of patients [111 patients (78.2%); 204.9 patients per 100PY] reported ≥ 1 TEAE, most of which were mild or moderate in intensity (Table 2) and transient in nature. A total of 18 patients (12.7%; 14.7 patients per 100PY) reported TEAEs that were judged by the investigator as being related to treatment, 6 patients (4.2%; 4.6 patients per 100PY) reported severe TEAEs, and 8 (5.6%; 6.2 patients per 100PY) reported a total of 9 serious TEAEs (6.8 events per 100PY) (Table 2). The nine serious events (listed here as MedDRA PTs) consisted of one event each of enterobiasis, dermatitis atopic, adenoidal hypertrophy, tonsillar hypertrophy, gastroenteritis viral, periorbital cellulitis, otitis media, otitis media acute, and diabetic ketoacidosis (Table S2; see the ESM). Of the serious TEAEs, all had resolved (one event of diabetic ketoacidosis had resolved with sequelae) by the time of the database lock (Table S2; see the ESM). Only one TEAE [severe urticaria (MedDRA PT)] led to permanent treatment discontinuation; however, the event resolved after 1 day (Table S3; see the ESM).

Table 2.

Safety assessment in the PED-OLE

| All patients (N = 142) |

||

|---|---|---|

| nE | nE/100PY | |

| Total number of TEAEs | 519 | 394.0 |

| Total number of serious TEAEs | 9 | 6.8 |

| Total number of severe TEAEs | 6 | 4.6 |

| Total number of TEAEs related to treatment | 28 | 21.3 |

| Total number of TEAEs related to permanent treatment discontinuationa | 1 | 0.8 |

| Total number of deaths | 0 | 0 |

| n (%) | nP/100PY | |

| Patients with any TEAE | 111 (78.2) | 204.9 |

| Patients with any serious TEAE | 8 (5.6) | 6.2 |

| Patients with any severe TEAE | 6 (4.2) | 4.6 |

| Patients with any TEAEs related to treatment | 18 (12.7) | 14.7 |

| Patients with any TEAEs leading to permanent discontinuationa | 1 (0.7) | 0.8 |

| Conjunctivitis (narrow)b | 18 (12.7) | 14.6 |

| Injection-site reactions (HLT)c | 3 (2.1) | 2.3 |

| Skin infections (SOC) (excluding herpes viral infections) | 24 (16.9) | 20.2 |

| Herpes viral infections (HLT) | 14 (9.9) | 11.0 |

| Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (PT) | 4 (2.8) | 3.1 |

| Skin papilloma (PT)d | 4 (2.8) | 3.1 |

| Most common TEAEs reported in ≥ 3% of patients (PT) | ||

| Nasopharyngitis | 28 (19.7) | 23.9 |

| Cough | 22 (15.5) | 18.3 |

| Pyrexia | 20 (14.1) | 16.4 |

| COVID-19 | 20 (14.1) | 15.9 |

| Dermatitis atopic | 16 (11.3) | 12.8 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 15 (10.6) | 12.3 |

| Rhinorrhea | 12 (8.5) | 9.6 |

| Conjunctivitis allergic | 8 (5.6) | 6.3 |

| Diarrhea | 8 (5.6) | 6.2 |

| Urticaria | 7 (4.9) | 5.5 |

| Vomiting | 7 (4.9) | 5.5 |

| Food allergy | 7 (4.9) | 5.5 |

| Ear infection | 6 (4.2) | 4.7 |

| Asthma | 5 (3.5) | 3.9 |

| Conjunctivitis | 5 (3.5) | 3.9 |

| Impetigo | 5 (3.5) | 3.9 |

| Conjunctivitis bacterial | 5 (3.5) | 3.8 |

| Otitis media | 5 (3.5) | 3.8 |

HLT MedDRA High Level Term, nE number of events, nE/100PY nE per 100 patient-years, nP/100PY number of patients per 100 patient-years, MCP metacarpalphalangeal, MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, PT MedDRA Preferred Term, SOC MedDRA System Organ Class, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

aPatient discontinued due to TEAE of severe urticaria

bConjunctivitis (narrow) includes PTs conjunctivitis, bacterial conjunctivitis, viral conjunctivitis, allergic conjunctivitis, and atopic keratoconjunctivitis; 15 patients (83%) had conjunctivitis (narrow) in the parent study

cMedDRA PTs for the three patients reporting injection-site reaction were: injection-site erythema, injection-site oedema, injection-site swelling, injection-site mass, and injection-site induration

dReported terms for the four patients reporting skin papilloma were: wart (left hand); wart (left foot); verruca vulgaris of left wrist; verruca vulgaris, right MCP joint middle finger; and verruca vulgaris (finger wart)

Five TEAEs of special interest [3.8 events per 100PY; 4 patients (2.8%); 129.6 patients per 100PY] were reported: two events of anaphylactic reaction (both were assessed by the investigator to be related to food allergy, and both were not related to treatment) and one event each of enterobiasis (related to treatment), blepharitis (related to treatment), and keratitis (assessed by the investigator as not related to treatment). All of these events were resolved at the time of the database lock (Table S4; see the ESM).

The most frequently reported TEAEs were: nasopharyngitis (19.7%; 23.9 patients per 100PY); cough (15.5%; 18.3 patients per 100PY); and pyrexia (14.1%; 16.4 patients per 100PY) (Table 2). Injection-site reactions (MedDRA high-level term, HLT) were reported in three patients (2.1%; 2.3 patients per 100PY); none of these events were serious, all were mild or moderate in severity, and none led to treatment discontinuation (Table 2).

Treatment-emergent conjunctivitis was reported in 18 patients (12.7%; 14.6 patients per 100PY), including conjunctivitis allergic (8 patients; 5.6%; 6.3 patients per 100PY), conjunctivitis (5 patients; 3.5%; 3.9 patients per 100PY), bacterial conjunctivitis (5 patients; 3.5%; 3.8 patients per 100PY), and viral conjunctivitis (1 patient; 0.7%; 0.8 patients per 100PY). All conjunctivitis events were mild or moderate, and the majority had resolved by the time of the database lock and did not recur with continued treatment (Table 2 and Table S5; see the ESM). Of these 18 patients, 15 (83.3%) had reported conjunctivitis TEAEs in the parent study, and 5 (27.8%) had reported history of conjunctivitis prior to the parent study (Table S5; see the ESM). Skin infections (excluding herpes viral infections) were reported in 24 patients (16.9%; 20.2 patients per 100PY) (Table 2). Herpes viral infections (MedDRA HLT) were reported in 14 patients (9.9%; 11.0 patients per 100PY), among which herpes simplex, oral herpes, and varicella infections were the most common, each being reported in 4 patients (2.8%; 3.1 patients per 100PY) (Table 2 and Table S6; see the ESM). Other skin structures and soft tissue infections (MedDRA HLT) were reported in ten patients (7.0%; 7.9 patients per 100PY), among which impetigo was the most common, being reported in five patients (3.5%; 3.9 patients per 100PY) (Table S6; see the ESM). Further details of conjunctivitis and skin infections are presented in Tables S5 and S6, respectively; see the ESM.

In patients younger than 2 years, the trends in safety data were similar to those observed in the overall population (Table S7; see the ESM); one patient in this age group experienced conjunctivitis and one experienced a non-herpes virus-related skin infection [impetigo (MedDRA PT)] (Table S7; see the ESM). However, it should be noted that this group consisted of only seven patients.

Efficacy Outcomes

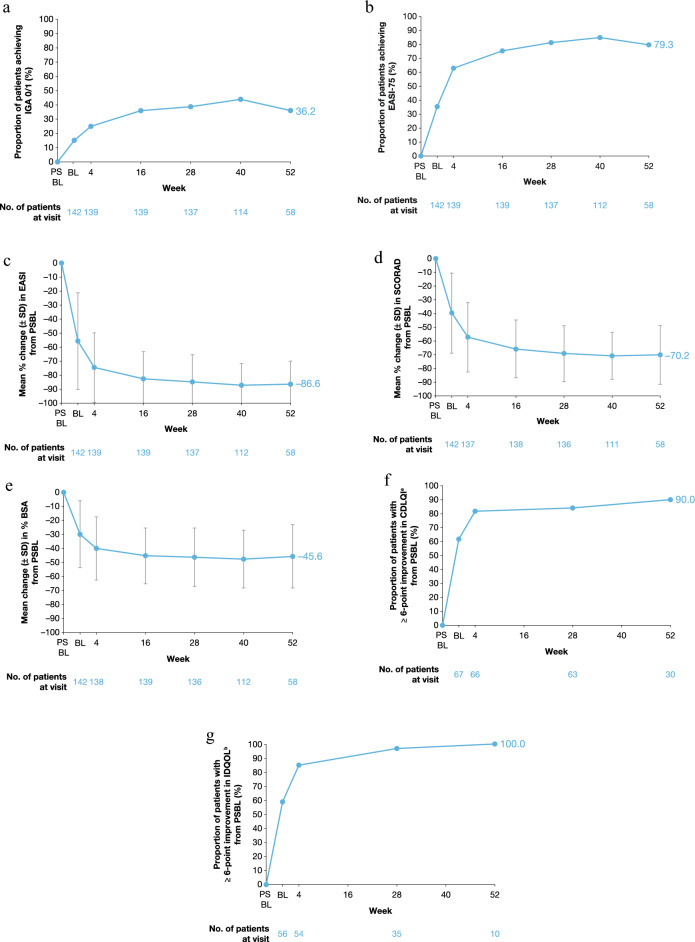

Efficacy data for the 142 patients included in the analysis are presented from the baseline of the parent study up to week 52 of treatment in the OLE (Fig. 2, Fig. S1; see the ESM). Clinical signs showed substantial and incremental improvements over time. The proportions of patients with an IGA score of 0/1 (Fig. 2a) or EASI-75 (Fig. 2b) increased from PSBL through week 52 of the PED-OLE. By week 52, 36.2% of patients (21/58) had an IGA score of 0/1, and 96.6%, 79.3%, and 58.6% of patients had EASI-50, EASI-75, and EASI-90, respectively (Table 3). Additionally, 91.4% of patients had mild disease or better (IGA ≤ 2) at week 52 of the PED-OLE (Fig. S2a; see the ESM).

Fig. 2.

Efficacy outcomes from parent study baseline through week 52 of the PED-OLE. BL baseline of OLE, BSA body surface area, CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-75 patients achieving a 75% reduction in EASI compared with PSBL, IDQOL Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, OLE open-label extension, PSBL parent study baseline, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SD standard deviation. aAmong patients with CDLQI ≥ 6 at PSBL. bAmong patients with IDQOL ≥ 6 at PSBL. Note: The safety analysis set included 60 patients; however, one patient did not perform the week 52 assessment due to varicella zoster infection and another due to COVID-19 infection.

Table 3.

Efficacy assessment at weeks 4, 16, and 52 in the PED-OLE

| All patients (N = 142) |

Week 4 (n = 139) |

Week 16 (n = 139) |

Week 52 (n = 58) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients achieving IGA 0 or 1, n (%) | 35 (25.2) | 50 (36.0) | 21 (36.2) |

| Proportion of patients achieving EASI-50, n (%) | 119 (85.6) | 126 (90.6) | 56 (96.6) |

| Proportion of patients achieving EASI-75, n (%) | 87 (62.6) | 104 (74.8) | 46 (79.3) |

| Proportion of patients achieving EASI-90, n (%) | 53 (38.1) | 64 (46.0) | 34 (58.6) |

| Percentage change from baseline of parent study in EASI, mean (SD) | −75.0 (24.3) | −82.2 (18.9) | −86.6 (16.3) |

| Change from baseline of parent study in EASI, mean (SD) | −24.9 (11.8) | −27.3 (11.3) | −26.9 (12.6) |

| Change from baseline of parent study in percent BSA affected by AD, mean (SD) |

−40.0 (22.5) (n = 138) |

−45.3 (19.8) | −45.6 (22.5) |

| Percentage change from baseline of parent study SCORAD, mean (SD) |

−57.4 (25.1) (n = 137) |

−65.8 (21.0) (n = 138) |

−70.2 (21.3) |

| Change from baseline of parent study in CDLQI, mean (SD) |

−11.1 (6.9) (n = 66) |

– |

−13.7 (6.4) (n = 30) |

| Proportion of patients with ≥ 6-point improvement in CDLQI, n/N1 (%)a | 54/66 (81.8) | – | 27/30 (90.0) |

| Change from baseline of parent study in IDQOL, mean (SD) |

−10.3 (6.4) (n = 55) |

– |

−15.0 (4.4) (n = 10) |

| Proportion of patients with ≥ 6-point improvement in IDQOL, n/N1 (%)a | 46/54 (85.2) | – | 10/10 (100.0) |

AD atopic dermatitis, BSA body surface area, CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-50/75/90 patients achieving a 50%/75%/90% reduction, respectively, in EASI compared with PSBL, IDQOL Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, N1 patients with non-missing scores at each week, PSBL parent study baseline SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SD standard deviation

aAmong patients with CDLQI ≥ 6 at PSBL or IDQOL ≥ 6 at PSBL

Similar incremental improvements through week 52 were seen for achievement of IGA 0/1 or EASI-75 in patients with body weight < 15 kg or ≥ 15 to < 30 kg (Fig. S1a and S1b in the ESM).

Mean percent changes from PSBL in EASI (Fig. 2c) and SCORAD (Fig. 2d) showed substantial improvement through week 52, with mean percent (SD) change of −86.6 (16.3) in EASI and −70.2 (21.3) in SCORAD at week 52. At week 52, mean (±SE) EASI was 4.2 (0.7), with mean (±SD) change in EASI from PSBL of −26.9 (12.6) (Fig. S2b and S2c; see the ESM). Again, a similar incremental improvement in EASI was seen through week 52 (Fig. S2c; see the ESM). The proportion of BSA affected by AD decreased from PSBL through week 52 (Fig. 2e), with a mean (SD) percent change in BSA affected by AD of −45.6 (22.5) at week 52 (Table 3).

Patients also showed improvement in health-related quality of life, with 90.0% (27/30) of patients aged ≥ 4 years having a ≥ 6-point improvement in CDLQI by week 52; many experienced this improvement as early as week 4 (Fig. 2f). Mean (SD) change in CDLQI from PSBL was −13.7 (6.4) at week 52 (Table 3). Similarly, among patients aged < 4 years, 100.0% (10/10) had ≥ 6-point improvement in IDQoL by week 52; many of these younger patients also experienced this improvement by week 4 (Table 3 and Fig. 2g). Mean (SD) change from PSBL in IDQoL was −15.0 (4.4) at week 52 (Table 3).

A similar trend in efficacy data was observed in patients younger than 2 years as was observed in the overall population (Table S8; see the ESM).

Discussion

Dupilumab is the first systemic treatment other than oral steroids, and the first biologic agent, approved by the US FDA for the treatment of children as young as 6 months with moderate-to-severe AD [25, 26]. In PED-OLE, dupilumab treatment for up to 52 weeks was well tolerated and provided sustained and substantial clinical benefit in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life in children aged 6 months to 5 years with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe AD.

The overall safety profile in children aged 6 months to 5 years was consistent with the results previously obtained in OLE trials in adults [29], adolescents [30], and children aged 6–11 years with AD [31]. Results presented here were also consistent with the safety profile seen in the 16-week phase 3 trial of dupilumab in this age group of patients with AD (PRESCHOOL part B) [27]. The number of events leading to permanent study drug discontinuation was low (nE per 100PY: 0.8) in this study: only one TEAE (severe urticaria) led to permanent study drug discontinuation; this event lasted for 1 day. This event was deemed related to the study drug by the investigator; however, it resolved rapidly and was not serious. There were nine serious TEAEs, of which one was considered related to dupilumab (enterobiasis); all resolved over time. The event of enterobiasis related to dupilumab was moderate in severity and the dupilumab dose was not changed due to this serious TEAE.

A total of 18 (12.7%) patients experienced conjunctivitis; all events were mild or moderate in severity, most (12/18) resolved by the time of database lock (remaining events were ongoing), and none led to discontinuation of treatment. In the PED-OLE, there was a low incidence of injection-site reactions (three patients; 2.1%); all were mild or moderate in severity, none were serious, and none led to treatment discontinuation. No reports of systemic hypersensitivity, including anaphylactic reactions, were considered to be related to dupilumab.

Overall, infections and infestations were reported in 35 (24.6%) patients. A total of 24 (16.9%) patients experienced a TEAE of skin infection (MedDRA System Organ Class, excluding herpes viral infections); none of these infections were severe or serious, and none led to treatment discontinuation. Furthermore, no opportunistic infections were reported in this patient subgroup with a developing immune system. In the 16-week phase 3 trial, dupilumab treatment resulted in lower rates of skin infections compared with placebo [27]. Similarly, in previous controlled studies in adults, adolescents, and older children, incidence of skin infection TEAEs was lower in the dupilumab arm compared with the placebo arm [32–36]. The profile of skin infections was consistent with what is typically seen in patients with AD in this age group [37, 38]. Since the patients enrolled in this study had a high level of disease severity at baseline, occurrence of these skin infections was not unexpected.

Although data in this subpopulation are limited and the dataset was small, the safety profile in patients aged < 2 years was consistent with that seen in the overall population. Dupilumab was consistently well tolerated across subgroups, including in patients aged < 2 years.

Clinical efficacy of dupilumab that was demonstrated in children aged 6 months to 5 years in PRESCHOOL part B was sustained in children with moderate-to-severe AD treated with dupilumab in PED-OLE for up to 1 year. Efficacy data for all patients enrolled in the PED-OLE (N = 142) demonstrated a substantial and progressively incremental clinical benefit of dupilumab with longer-term treatment. Improvements were observed across efficacy endpoints. Notably, 90% of children ≥ 4 years and 100% of children < 4 years experienced a clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life as measured by CDLQI and IDQoL, respectively. Similar trends for substantial and sustained clinical benefit were seen in patients aged < 2 years. Improvements in efficacy endpoints were also independent of patient weight. The significant clinical benefit experienced with dupilumab treatment, coupled with the acceptable safety profile, are aligned with the high retention rate in the study.

A key strength of this analysis is that this is the first long-term study (through 1 year) of dupilumab safety and efficacy, or any biologic agent, in infants and young children aged 6 months to 5 years. This ongoing study will provide additional information about the safety and efficacy of this treatment in pediatric patients over several years. Limitations of this analysis include the open-label, non-randomized nature of the study, the fact that concomitant use of TCS and other AD therapies was not standardized, the small sample size of patients aged < 2 years, and that efficacy data are reported as observed and do not account for potential confounding factors resulting from additional AD therapies. Notably, there was no imputation for patients who withdrew from the study (n = 10) and not all patients had completed the week 52 visit. Another limitation was the small number of patients for whom data were available after discontinuation of dupilumab post-remission. These data continue to be accumulated, as the study is ongoing, and will be presented in a subsequent manuscript. Finally, additional important questions remain for further investigation, including immunization safety and efficacy (manuscript in development), pharmacokinetic analysis (manuscript in development), rate of relapse off-treatment, durability of response after restarting, and whether early intervention in this age group can modify the course of the disease.

Conclusions

Dupilumab treatment demonstrated an acceptable long-term safety profile and sustained efficacy in children aged 6 months to 5 years with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe AD. These results support long-term continuous use of dupilumab in this patient population. The dupilumab long-term safety profile was comparable with that previously observed in AD. Further studies in children aged 6 months to 5 years treated with dupilumab are ongoing to evaluate longer-term safety and efficacy in this age group.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families for their participation in these studies, their colleagues for their support, and Leonard Lionnet, Purvi Smith (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.), and Adriana Mello (Sanofi) for their contributions.

Declarations

Funding

This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT02612454 and NCT03346434 part B). The study sponsors participated in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication. Medical writing/editorial assistance was provided by Ekaterina Semenova, PhD, and Vicki Schwartz, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., according to the Good Publication Practice guideline.

Availability of Data and Material

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, and statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the indication has been approved by a regulatory body, if there is legal authority to share the data, and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant reidentification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org.

Conflicts of Interest

Amy S. Paller is an investigator for AbbVie, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Krystal Biotech, LEO Pharma, and UCB; a consultant for Amryt Pharma, Azitra, BioCryst, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Castle Creek Biosciences, Eli Lilly, InMed Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Krystal Biotech, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Seanergy, TWI Biotechnology, and UCB; and a member of the data safety monitoring board for AbbVie, Abeona, Catawba Research, Galderma, and InMed Pharmaceuticals. Elaine C. Siegfried is a consultant for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, and Verrica Pharmaceuticals; a member of the data safety monitoring board for Esperare, LEO Pharma, Novan, Pfizer, and UCB; and a principal investigator in clinical trials for Amgen, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Sanofi. Eric L. Simpson has received personal fees from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Collective Acumen, Eli Lilly, Forté Biosciences, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Roivant Sciences, Sanofi, and Valeant; and has received grants/is a principal investigator for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Tioga Pharmaceuticals, and Vanda Pharmaceuticals. Michael J. Cork is an investigator and/or consultant for AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, Boots, Dermavant, Galapagos, Galderma, Hyphens Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Oxagen, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Sanofi. Robert Sidbury is an investigator for Castle Creek Biosciences, Galderma, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and UCB; an advisory board member for Pfizer; a consultant for Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, and Micreos; and is in a speaker’s bureau for Beiersdorf. Iris H. Chen and Ariane Dubost-Brama are employees of Sanofi and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company. Faisal A. Khokhar, Jing Xiao, and Ashish Bansal are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Authors’ Contributions

A.B. contributed to the study conception and design; A.S.P., E.C.S., E.L.S., M.J.C., and R.S. contributed to the acquisition of data; and I.H.C. and J.X. contributed to the statistical analysis of the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data, commented on previous versions of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Approval

The study was conducted following the ethical principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, Good Clinical Practice, and local applicable regulatory requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and the patients’ parents/guardians prior to commencement of any study treatment. At each study site, the protocol, informed-consent form (ICF), and patient information were approved by an institutional review board and independent ethics committee.

Consent to Participate

All patients provided written consent/assent, and at least one parent or guardian for each adolescent patient provided written informed consent. All people named in the Acknowledgements section gave written permission to be named in the manuscript.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Amy S. Paller and Elaine C. Siegfried contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Grüber C, Niggemann B, et al. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(50):925–931. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, Simpson EL, Weidinger S, Mina-Osorio P, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international, epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(4):417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bylund S, von Kobyletzki LB, Svalstedt M, Svensson A. Prevalence and incidence of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(12):adv00160. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volke A, Toompere K, Laisaar K-T, Oona M, Tisler A, Johannson A, et al. 12-month prevalence of atopic dermatitis in resource-rich countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):15125. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-19508-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomsen SF. Atopic dermatitis: natural history, diagnosis, and treatment. ISRN Allergy. 2014;2014:354250. doi: 10.1155/2014/354250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22(2):125–137. doi: 10.5021/ad.2010.22.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Association between severe eczema in children and multiple comorbid conditions and increased healthcare utilization. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24(5):476–486. doi: 10.1111/pai.12095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geoghegan JA, Irvine AD, Foster TJ. Staphylococcus aureus and atopic dermatitis: a complex and evolving relationship. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26(6):484–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyons JJ, Milner JD, Stone KD. Atopic dermatitis in children: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015;35(1):161–183. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DH, Li K, Seo SJ, Jo SJ, Yim HW, Kim CM, et al. Quality of life and disease severity are correlated in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27(11):1327–1332. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.11.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. A comparative study of impairment of quality of life in children with skin disease and children with other chronic childhood diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(1):145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forrest CB, Schuchard J, Bruno C, Amaral S, Cox ED, Flynn K, et al. Self-reported health outcomes of children and youth with 10 chronic diseases. J Pediatr. 2022;246:207–212.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricci G, Patrizi A, Baldi E, Menna G, Tabanelli M, Masi M. Long-term follow-up of atopic dermatitis: retrospective analysis of related risk factors and association with concomitant allergic diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5):765–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang EJ, Beck KM, Sekhon S, Bhutani T, Koo J. The impact of pediatric atopic dermatitis on families: a review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(1):66–71. doi: 10.1111/pde.13727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gustafsson D, Sjöberg O, Foucard T. Development of allergies and asthma in infants and young children with atopic dermatitis—a prospective follow-up to 7 years of age. Allergy. 2000;55(3):240–245. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JP, Chao LX, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI. Persistence of atopic dermatitis (AD): a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(4):681–7.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paller AS, Guttman-Yassky E, Schuttelaar MLA, Irvine AD, Baselga E, Kataoka Y, et al. Disease characteristics, comorbidities, treatment patterns and quality of life impact in children <12 years old with atopic dermatitis: interim results from the PEDISTAD Real-World Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(5):1104–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis DMR, Drucker AM, Alikhan A, Bercovitch L, Cohen DE, Darr JM, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with phototherapy and systemic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.08.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macdonald LE, Karow M, Stevens S, Auerbach W, Poueymirou WT, Yasenchak J, et al. Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5147–5152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323896111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy AJ, Macdonald LE, Stevens S, Karow M, Dore AT, Pobursky K, et al. Mice with megabase humanization of their immunoglobulin genes generate antibodies as efficiently as normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5153–5158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NMH, Pirozzi G, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):35–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le-Floc’h A, Allinne J, Nagashima K, Scott G, Birchard D, Asrat S, et al. Dual blockade of IL-4 and IL-13 with dupilumab, an IL-4Rα antibody, is required to broadly inhibit type 2 inflammation. Allergy. 2020;75(5):1188–1204. doi: 10.1111/all.14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(5):425–437. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1298443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haddad EB, Cyr SL, Arima K, McDonald RA, Levit NA, Nestle FO. Current and emerging strategies to inhibit type 2 inflammation in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidleb). 2022;12(7):1501–1533. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00737-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. DUPIXENT® (dupilumab). Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2023. https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/dupixent_fpi.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2023.

- 26.European Medicines Agency (EMA). DUPIXENT® (dupilumab). Summary of Product Characteristics. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/all-authorised-presentations/dupixent-epar-all-authorised-presentations_en.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2023.

- 27.Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, Cork MJ, Wollenberg A, Arkwright PD, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10356):908–919. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.European Medicines Agency (EMA). DUPIXENT® (dupilumab). Summary of opinion (post-authorisation). 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/smop/chmp-post-authorisation-summary-positive-opinion-dupixent-ii-60_en.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2023.

- 29.Deleuran M, Thaçi D, Beck LA, de Bruin-Weller M, Blauvelt A, Forman S, et al. Dupilumab shows long-term safety and efficacy in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis enrolled in a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, Paller AS, Simpson EL, Cork MJ, Weisman J, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results through Week 52 from a Phase III open-label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE) Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(3):365–383. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00683-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cork MJ, Thaçi D, Eichenfield L, Arkwright PD, Chen Z, Thomas RB, et al. Dupilumab safety and efficacy in a Phase III open-label extension trial in children 6–11 years of age with severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidleb). 2023 doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-01016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Two Phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, Reich K, Cork MJ, Radin A, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ) Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1083–1101. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287–2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, Wollenberg A, Cork MJ, Arkwright PD, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1282–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Boguniewicz M, Sher L, Gooderham MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a Phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):44–56. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ong PY, Leung DYM. Bacterial and viral infections in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(3):329–337. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill SE, Yung A, Rademaker M. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and antibiotic resistance in children with atopic dermatitis: a New Zealand experience. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52(1):27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.