Abstract

Ion channels are critical in enabling ion movement into and within cells and are important targets for pharmacological interventions in different human diseases. In addition to their ion transport abilities, ion channels interact with signalling and scaffolding proteins, which affects their function, cellular positioning, and links to intracellular signalling pathways. The study of “channelosomes” within cells has the potential to uncover their involvement in human diseases, although this field of research is still emerging. LRRC8A is the gene that encodes a crucial protein involved in the formation of volume-regulated anion channels (VRACs). Some studies suggest that LRRC8A could be a valuable prognostic tool in different types of cancer, serving as a biomarker for predicting patients’ outcomes. LRRC8A expression levels might be linked to tumour progression, metastasis, and treatment response, although its implications in different cancer types can be varied. Here, publicly accessible databases of cancer patients were systematically analysed to determine if a correlation between VRAC channel expression and survival rate exists across distinct cancer types. Moreover, we re-evaluated the impact of LRRC8A on cellular proliferation and migration in colon cancer via HCT116 LRRC8A-KO cells, which is a current topic of debate in the literature. In addition, to investigate the role of LRRC8A in cellular signalling, we conducted biotin proximity-dependent identification (BioID) analysis, revealing a correlation between VRAC channels and cell-cell junctions, mechanisms that govern cellular calcium homeostasis, kinases, and GTPase signalling. Overall, this dataset improves our understanding of LRRC8A/VRAC and explores new research avenues while identifying promising therapeutic targets and promoting inventive methods for disease treatment.

Subject terms: Chloride channels, Protein-protein interaction networks

Introduction

Ion channels mediate the movement of ions across cellular membranes and play important roles in the development and progression of several human diseases [1–4]. Channel proteins are complex structures consisting of a central ion-selective pore and various interacting proteins. Channel-interacting proteins (CIPs) can play a critical role in regulating biophysical properties, such as permeability and gating, or act as signalling and scaffolding proteins that influence the interaction of ion channels with upstream and downstream cellular signalling pathways [1–3, 5, 6].

The increasing knowledge of ion channels as macromolecular signalling complexes is transforming research methods in this field. Although high-throughput gene profiling techniques are commonly employed, studying the ion channel interactome, or channelosome, can reveal interconnected networks that affect not only ion channel activity but also complex signalling pathways. This approach is crucial in identifying groups of molecules that could act as targets for interventions aiming to manage or ameliorate pathological conditions. Additionally, it is essential to acknowledge that network-based approaches provide a more nuanced comprehension of the complex pathways involved in disease.

The identification of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) within a cellular context presents significant challenges, as conventional methods often prove ineffective in a natural cellular environment. Classical approaches may fail to ensure the detection of interactions involving weak or transient interactors, as well as those subject to spatio-temporal regulation. These limitations result in a substantial loss of valuable information, stemming from an incomplete understanding of the dynamic nature of these interactions. Initially, research in CIPs field mainly focused on cation channels, particularly those selectively permeable to calcium, potassium, and sodium ions. Nevertheless, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in anion channels, i.e., chloride (Cl) channels. These channels play a vital role in various cellular processes and their abnormal expression and/or function is associated with various human diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, myotonia, epilepsy, hyperekplexia, lysosomal storage diseases, deafness, renal salt wasting, kidney stones, osteopetrosis and numerous tumour development of numerous types of tumours [7–9].

Among anion channels, the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC) is emerging as a promising pharmacological target in human pathology and oncology. VRAC has a broad permeability, enabling the transfer of Cl- and other anions, organic compounds, neurotransmitters, taurine, and signalling molecules [10–15]. VRAC plays a critical role in regulating cell volume by reducing it through a process called regulatory volume decrease (RVD) and maintaining cell volume homeostasis. Due to its role in RVD, VRAC has been proposed to be involved in cell volume changes during different aspects of cancer cell behaviour and response to therapies. The activity of VRAC has been linked to cancer cell proliferation, metastasis, and multidrug resistance [11, 16]. Nonetheless, the biological function and prognostic value of the gene encoding the pore-forming subunit of VRAC, LRRC8, require better delineation, as contrasting results have been reported.

In this work, we examined the publicly accessible TCGA database to comprehensively analyse the relationship between LRRC8 expression in cancer and patient survival. We focused specifically on the colon cancer context.

Despite the functional characterization of VRAC has been known for several decades, its molecular identity has been unveiled only recently [17, 18]. These investigations shed light on VRAC as a heteromeric assembly that consists of subunits belonging to the LRRC8 gene family, comprising of five distinct members (LRRC8A-E) [17, 18]. Evolutionary, LRRC8 proteins are formed by combining a pannexin-like transmembrane protein and an intracellular leucine-rich repeat domain (LRRD) [19]. LRRC8 proteins are made up of four transmembrane segments and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat domain. The N-terminal domain was recently found to fold back into the pore from the cytoplasm, taking part in determining ion selectivity and possibly gating [20]. The precise proportions and arrangement of subunits needed to create functional LRRC8 heteromers have not yet been fully discovered. To operate efficiently, VRAC necessitates the presence of LRRC8A and at least one subunit among the LRRC8B-E isoforms [17, 18]. Recently, in cryoEM studies of heteromeric LRRC8A/LRRC8C complexes, different stoichiometries have been reported: Rutz et al. found 4 LRRC8A subunits and 2 LRRC8C subunits in heteromers [21], while Kern et al. reported a 5 LRRC8A/1 LRRC8C architecture [22]. In general, most cells express more than two different LRRC8 genes and LRRC8A-E assemble in various configurations, leading to the formation of VRACs with differing functional characteristics. At present, we have limited knowledge of the identities of the subunits that compose the VRAC pore, as well as how the channel is activated by cellular swelling.

Over the past three decades, intensive research endeavours have unveiled an extensive network of potential PPIs that exert a pivotal role in modulating the activity of VRAC. Experimental evidence indicates that the activation of VRAC currents can be achieved through purinergic signalling [23], a process involving calcium (Ca2+) signalling and protein phosphorylation events [24], as well as by the activation of bradykinin receptor signalling, which is intricately regulated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Ca2+ nanodomains [23, 25]. Furthermore, ROS have been suggested to influence the activation of VRAC by EGF [26]. Additionally, VRAC can be induced isovolumetrically by intracellular GTPγS [27, 28]. Volume-independent activation of VRAC is also induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate, which is generated by bacterial lipopolysaccharide-activated S-kinase, PDGF, TNFα, thrombin, IgE-bound antigen, and especially ATP [29].

Despite considerable effort, there is an insufficient amount of information available on its signalling networks. In 2016, Syeda et al. generated a cell line expressing LRRC8A with a FLAG-tag to biochemically investigate the protein and its associated partners [30]. The detection of an 800-kDa complex in native gels implies potential interactions between LRRC8 subunits and other proteins. The authors used mass spectrometry (MS) to identify the proteins associated with LRRC8A. Only peptides from the four LRRC8 family members were detected, and no other binding partners were found. Probably, the lack of data on VRAC interaction factors in the literature owes to the channel’s hydrophobicity and the technical challenges associated with biochemical manipulation. Indeed, in the authors themselves, suggest that the use of detergents and the tag affinity purification process may have resulted in the loss of probable associations [30].

In the present investigation, we have undertaken an in-depth exploration of the PPI network associated with LRRC8A. This endeavour was accomplished by the application of the state-of-the art BioID technique, with a specific emphasis on the central subunit LRRC8A. We exploited the BioID methodology to construct an exhaustive compendium of proteins engaged in interactions with LRRC8A/VRAC. These interactions encompass a spectrum of strengths, temporal dynamics, and indirect connections. The discerned proteins are presumed to establish close or direct functional affiliations with the LRRC8A subunit, thereby harbouring the potential to bestow valuable insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms and underlying functional roles.

Results

LRRC8s alterations and expression in human cancers: impact on patient survival

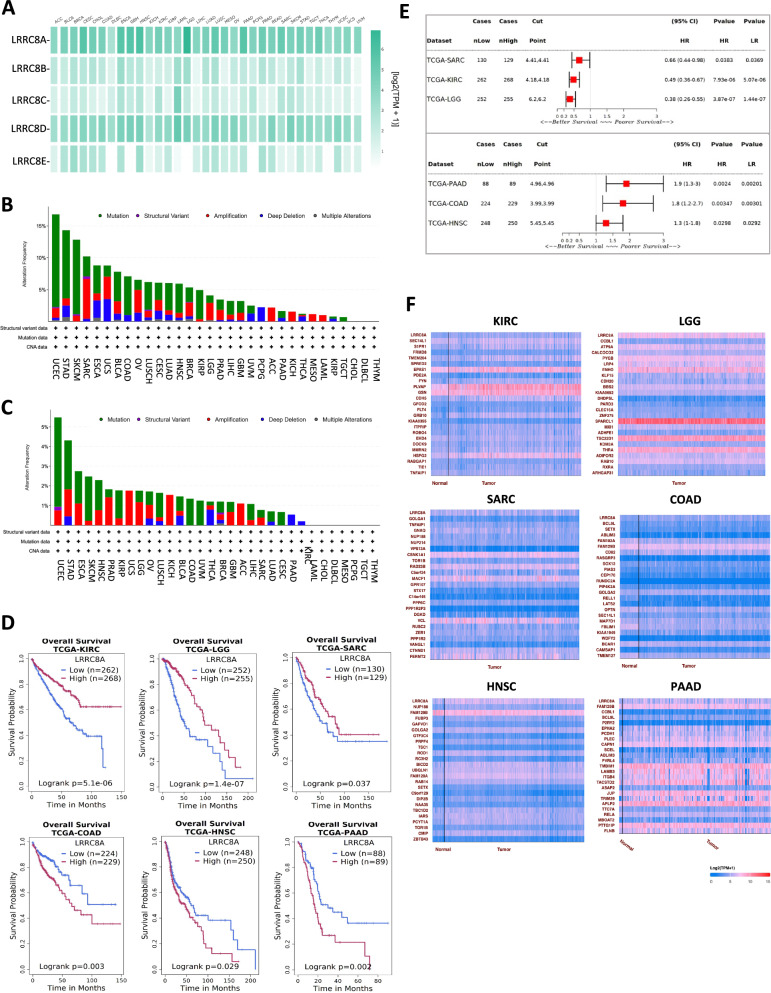

The GEPIA database [31] was used to evaluate the expression profile of LRRC8 genes. A comparative analysis of multiple genes revealed that LRRC8A and LRRC8D exhibit higher expression in tumours when compared to other LRRC8 genes, providing an overall characterization (Fig. 1A). Exploring the publicly accessible TCGA database enabled us to systematically investigate the correlation between VRAC channels in specific cancer types and patient survival. To assess comprehensive alterations, we analysed all LRRC8 genes (LRRC8A-E) using the TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas dataset, combining data from 32 human cancers, encompassing a total of 10,953 patients. Genetic alterations within the cBioPortal database were categorized as mutations, deep deletions, gene amplifications, structural variants, and multiple alterations [32, 33]. The graphical representation depicting cancer types illustrates a discernible pattern of genomic alterations in LRRC8 genes across the TCGA PanCancer cohorts (Fig. 1B). The results indicate that the 10 types of cancer with the highest frequency of alterations were uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), sarcoma (SARC) and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (ESCA), uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS), bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), colorectal adenocarcinoma (COAD), ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV), and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC). The cumulative mutation frequency ranged from 16.82% for UCEC to 6.16% for LUSC. Truncating, in-frame, or missense mutations were prevalent in LRRC8 genes, while amplifications, multiple alterations, or deep deletions, especially homozygous deletions in non-aneuploidy cases, were less frequently observed. Figure 1C delineates the specific genetic alterations of the LRRC8A gene.

Fig. 1. LRRC8s family in human cancers.

A Differential expression of LRRC8s family in human cancers. LRRC8s multiple gene comparison was performed using TCGA and GTEx datasets and using the GEPIA database. Data were normalized as transcripts per kilobase million (TPM) values. TPM values were converted to log2-normalized transcripts per million [log2(TPM + 1)]. B Mutation frequencies of LRRC8s in 32 cancer studies were retrieved from cBioPortal (TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas dataset). C Mutation frequencies of LRRC8A in 32 cancer studies were retrieved from cBioPortal (TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas dataset). D Survival plots based on LRRC8A expression level in represented tumours were obtained through Kaplan–Meier analysis by sorting samples for high and low LRRC8A expression groups according to Survival Genie software. E The forest plot illustrates hazard ratio (HR) analyses. The results of the Wald test (HR P-value) and log-rank test (LR P-value) are also displayed. F LRRC8A correlated differentially expressed genes and related pathways. The top 25 positively LRRC8A co-expressed genes were mapped using the TCGA KIRC, LGG, SARC, COAD, HNSC, and PAAD datasets in the ULCAN database.

To highlight the prognostic impact of LRRC8A expression in patients with cancer, we evaluated the Kaplan-Meier analysis to classify samples into groups with high and low LRRC8A expression. Our findings indicate a significant association between LRRC8A expression levels and patient prognosis across six different types of cancer. Patients with high LRRC8A levels had a significantly worse prognosis in cases of COAD, Head-Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSC), and Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD). Conversely, Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), Low-grade glioma (LGG), and SARC demonstrated a favourable outcome (Fig. 1D). However, statistically significant results were not obtained for other types of tumours. The forest plot (Fig. 1E) illustrating hazard ratio (HR) analyses, was generated using the Survival Genie software, a web-based platform designed for conducting survival analyses in both paediatric and adult cancer populations [16]. This graph illustrates the HR and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for two distinct groups analysed univariably. The results of the Wald test (HR P-value) and log-rank test (LR P-value) are also displayed. Important details, such as the cut-off point used to classify patients as having high or low expression, and the sample sizes for each group, are provided. In the figure, the hazard ratio is represented by a central box (significant correlations are highlighted in red), and the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval are indicated by horizontal lines. For example, for COAD, the patients were divided into two groups, namely high (n = 229 samples) and low (n = 224 samples). It has been established those patients in the high group, with a median cut-off point of 3.99, exhibit an unfortunate prognosis (HR = 1.8; 95% CI 1.2-2.7; P = 0.00347 by Wald-test, and P = 0.0030 by log-rank test) (Fig. 1E).

Fascinated by the dual role of LRRC8A/VRAC in tumours, which is linked to both favourable and unfavourable prognoses (as illustrated in Fig. 1D and E), our aim was to recognize differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to LRRC8A to illuminate its functional roles (Fig. 1F). To achieve this objective, a thorough examination of genes with a positive correlation to LRRC8A in KIRC, LGG, SARC, COAD, HNSC, and PAAD tumour types was conducted in their respective TCGA datasets. This was accomplished by utilizing the UALCAN database [34, 35]. Over 100 differentially DEGs were found to be shared between tumour types associated with both a positive prognosis (KIRC, LGG, and SARC) and those linked to a negative prognosis (COAD, HNSC and PAAD,) within the TCGA tumours datasets. This suggests that these common genes may play a critical role in tumour progression and outcome. The levels of LRRC8A transcripts discovered in different tumours and the difference in LRRC8A expression between normal and tumours tissue lack justification for the impact of genes on survival, suggesting that aspects beyond gene expression need to be studied.

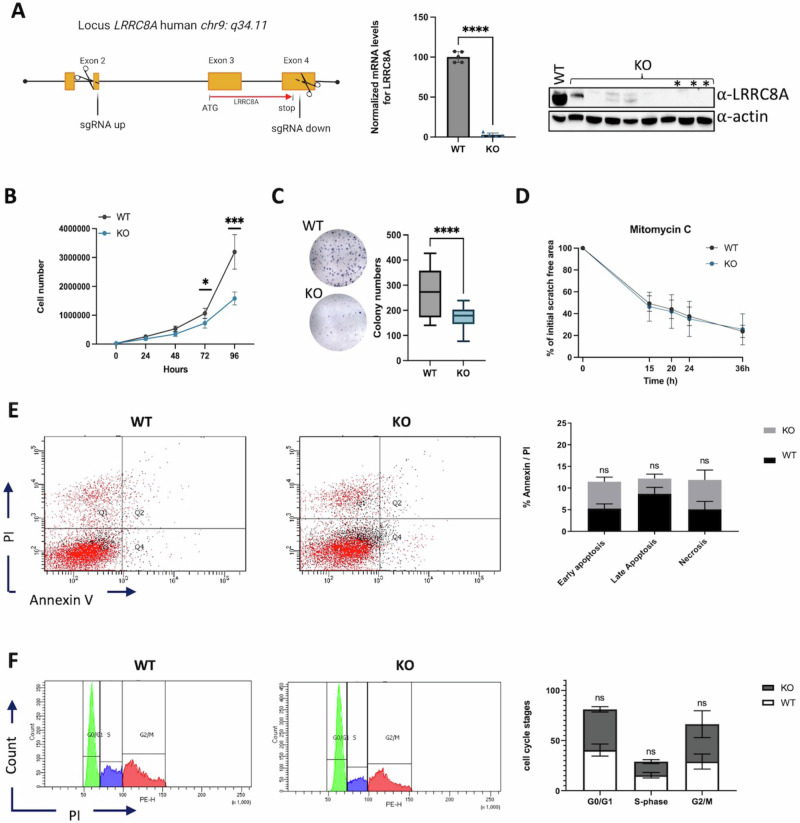

Our in-depth analysis, as illustrated in Fig. 2 supports the above findings and specifically examines the effects of LRRC8A deletion on HCT116 cell behaviour. The increased expression of LRRC8A seems to be linked with reduced survival among CRC patients with positive lymph nodes, indicating LRRC8A proteins’ possible involvement in CRC metastasis by aiding cell migration [36]. However, these findings contradict those reported by Liu et al. [37], who showed that the deletion of LRRC8A or all members of LRRC8 did not reduce the migration of HCT116 cells. To gain new insights, we employed CRISPR/Cas9 technology to generate a new LRRC8A-deficient HCT116 knockout cell line. Our model completely removed the LRRC8A gene, and we isolated two independent monoclonal cell lines for further analysis. Target site-specific PCR was utilized to evaluate any modifications in the genomic DNA sequence. The lack of LRRC8A expression was verified by Sanger sequencing, Western blot, and RT-qPCR (Fig. 2A). To investigate the potential effects of LRRC8A, cell proliferation and wound healing assays were performed on HCT116 cells that either expressed or lacked LRRC8A (Fig. 2B–D). Cell counting over a period of up to 96 hours demonstrated a significant decrease in proliferation rate for the KO clones in comparison to the WT controls at both 72 hours (p = 0.0130) and 96 hours (p < 0.0001), suggesting an involvement of LRRC8A in cell proliferation (Fig. 2B). To further explore the influence of LRRC8A on cell proliferation further, a colony formation assay was conducted. The data demonstrated a substantial reduction (p < 0.0001) in colony count for the KO clones relative to the controls, consistent with the outcomes of the cell proliferation assay (Fig. 2C). Finally, we explored the function of LRRC8A in cell migration via a wound healing assay. Supplementary treatment of cells with mitomycin C validated that the formation of a confluent cell monolayer post-scratching was attributed to migration proficiency rather than cellular proliferation. No significant differences were found in the migration rate between the controls and KO clones during both experimental conditions (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. Characterization of LRRC8A knockout HCT116 cells.

A Strategy of CRISPR/Cas9 editing applied for LRRC8A and characterization of LRRC8A KO HCT116 cells. KO-LRRC8A monoclonal HCTT16 cell lines were isolated and evaluated for the expression of their LRRC8A gene using real-time qPCR. HCT116 WT cells were used as a control, and the housekeeping genes ACTB and TBP were employed. Gene expression data were normalised to the control and presented as a percentage variation (n = 5, one-way ANOVA, ****p < 0.0001). In addition, the α-LRRC8A antibody was used to assess the protein expression of LRRC8A, with HCT116 WT cells as the control. Protein extracts (50 μg) were loaded for each sample, with actin serving as the loading control. Single clones indicated by a red asterisk were selected for further analysis. B Growth curves of KO- and WT-LRRC8A HCT116 cells. At the 96-hour, it was found that KO clones exhibited a lower proliferation rate compared to HCT116 WT control (n = 4, two-way ANOVA, ***p-value < 0.001). C Colony formation assay. LRRC8A-KO cells formed significantly fewer colonies compared to HCT116 WT control (n = 5, one-way ANOVA, *p-value < 0.5). D The Wound Healing Assay examined migratory capacity by measuring the percentage of the initial scratch area free at various time points (from t = 0 h to t = 36 h) using ImageJ software. In both experimental settings (mitomycin 5 μg/mL), HCT116 WT control and LRRC8A-KO clones displayed no significant differences in scratch closure speed (n = 4, two-way ANOVA). Illustrative histograms showing HCT116 WT and KO clone. Statistical analysis of independent triplicate experiments showed non-significant differences between WT and the KO cells in terms of apoptosis (E) and cell cycle (F). Data were compared by Nonparametric T- test with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Numerous studies have suggested that LRRC8A supports cell survival under hypotonic conditions and facilitates tumorigenesis by suppressing apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo [38, 39]. Consequently, we investigated the influence of LRRC8A on apoptosis in HCT116 WT and KO cells using an Annexin V/propidium iodide assay. However, our results revealed no discernible impact on apoptosis events with the deletion of LRRC8A (Fig. 2E). Additionally, the analysis of the cell cycle did not reveal any significant differences in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases (Fig. 2F).

Identification and Analysis of the LRRC8A Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in colon Cancer

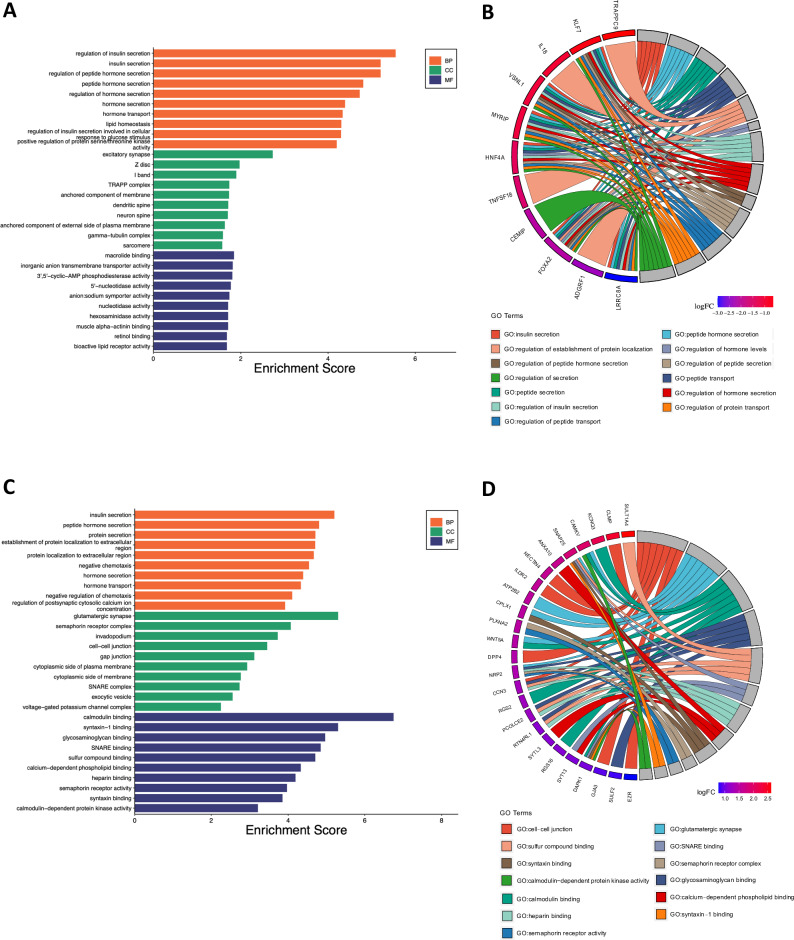

An RNA-Seq analysis was conducted to assess the impact of the LRRC8A deletion on HCT116 gene expression. A total of 125 genes displayed differential expression in LRRC8A KO versus WT cells: 56 genes being down-regulated and 69 up-regulated in LRRC8A KO cells (Table 1). Figure 3 shows the Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment scores for genes that were identified as either down-regulated or up-regulated. Panels 3A and 3C illustrate the GO enrichment for down-regulated and up-regulated genes, respectively. The enrichment bars are categorized by Biological Processes (BP) in orange, Cellular Components (CC) in green, and Molecular Functions (MF) in blue. Greater enrichment significance is indicated by longer bars, suggesting a more substantial association with the set of genes being analyzed. For example, in Fig. 3A, processes such as ‘regulation of insulin secretion’ show notable enrichment, indicating significant down-regulation. Figure 3C shows that the up-regulated genes are significantly enriched in processes such as ‘insulin secretion’ and components such as ‘cell junctions’. Functions such as ‘calmodulin binding’ are particularly prominent. Figures 3B and D display chord diagrams that visually represent the relationships between genes and their corresponding GO terms. Figure 3B shows down-regulated genes, while Fig. 3D shows up-regulated genes. The outer circle of each diagram lists genes, which are connected by coloured chords to specific GO terms that describe BP, CC, and MF. These chords display the network of associations between genes and their functions or locations within the cell. The chords are colour-matched with the corresponding GO categories they represent. On the gene side, a colour gradient illustrates the log-fold change (logFC) in gene expression. Warmer colours indicate a higher degree of down- or up-regulation. These diagrams summarise the complex interactions and functional implications of the observed changes in gene expression in the study.

Table 1.

DEGs in LRRC8A KO CRC cells.

| Differentially Expressed Genes (DEG) | ||

|---|---|---|

| ADGRF1 | ENSG00000153292 | DOWN |

| ALDH8A1 | ENSG00000118514 | UP |

| ANKRD22 | ENSG00000152766 | DOWN |

| ANXA10 | ENSG00000109511 | UP |

| APOBEC3G | ENSG00000239713 | UP |

| ARHGAP29 | ENSG00000137962 | DOWN |

| ARHGEF10L | ENSG00000074964 | DOWN |

| ARRDC4 | ENSG00000140450 | UP |

| ATP2B2 | ENSG00000157087 | UP |

| B3GALT5 | ENSG00000183778 | UP |

| CACNB4 | ENSG00000182389 | UP |

| CAMKV | ENSG00000164076 | UP |

| CCN3 | ENSG00000136999 | UP |

| CD24 | ENSG00000272398 | DOWN |

| CEMIP | ENSG00000103888 | DOWN |

| CLMP | ENSG00000166250 | UP |

| CPLX1 | ENSG00000168993 | UP |

| CRYBG1 | ENSG00000112297 | DOWN |

| CRYZL2P | ENSG00000242193 | DOWN |

| DAPK1 | ENSG00000196730 | UP |

| DPP4 | ENSG00000197635 | UP |

| DYNLT1 | ENSG00000146425 | UP |

| EZR | ENSG00000092820 | UP |

| FAM222A-AS1 | ENSG00000255650 | UP |

| FOXA2 | ENSG00000125798 | DOWN |

| FRMD4B | ENSG00000114541 | DOWN |

| FRMPD3 | ENSG00000147234 | UP |

| GARIN5A | ENSG00000142530 | DOWN |

| GGT5 | ENSG00000099998 | DOWN |

| GJA3 | ENSG00000121743 | UP |

| GPAT3 | ENSG00000138678 | UP |

| GPD1 | ENSG00000167588 | UP |

| GPR55 | ENSG00000135898 | UP |

| GREB1L | ENSG00000141449 | UP |

| GTF2H5 | ENSG00000272047 | UP |

| HKDC1 | ENSG00000156510 | UP |

| HNF4A | ENSG00000101076 | DOWN |

| IKZF2 | ENSG00000030419 | DOWN |

| IL18 | ENSG00000150782 | DOWN |

| ILDR2 | ENSG00000143195 | UP |

| INAVA | ENSG00000163362 | DOWN |

| KCNQ3 | ENSG00000184156 | UP |

| KLF7 | ENSG00000118263 | DOWN |

| KLRK1-AS1 | ENSG00000245648 | DOWN |

| LCN2 | ENSG00000148346 | DOWN |

| LGR4 | ENSG00000205213 | UP |

| LINC00698 | ENSG00000244342 | DOWN |

| LINC02593 | ENSG00000223764 | UP |

| LNCOC1 | ENSG00000253741 | DOWN |

| LOC102723553 | ENSG00000273590 | DOWN |

| LPAR1 | ENSG00000198121 | DOWN |

| LRRC8A | ENSG00000136802 | DOWN |

| LYPD3 | ENSG00000124466 | UP |

| MECOM + B58:B124 | ENSG00000085276 | UP |

| MEF2C | ENSG00000081189 | UP |

| MGLL | ENSG00000074416 | UP |

| MNS1 | ENSG00000138587 | DOWN |

| MTUS1-DT | ENSG00000253671 | DOWN |

| MYRIP | ENSG00000170011 | DOWN |

| NAPRT | ENSG00000147813 | DOWN |

| NAV2 | ENSG00000166833 | DOWN |

| NAV3 | ENSG00000067798 | DOWN |

| NECTIN4 | ENSG00000143217 | UP |

| NEMP2-DT | ENSG00000233654 | DOWN |

| NFIB | ENSG00000147862 | DOWN |

| NR2F1 | ENSG00000175745 | DOWN |

| NR2F1-AS1 | ENSG00000237187 | DOWN |

| NRIP1 | ENSG00000180530 | DOWN |

| NRP2 | ENSG00000118257 | UP |

| NT5E | ENSG00000135318 | DOWN |

| PALLD | ENSG00000129116 | DOWN |

| PCAT2 | ENSG00000254166 | DOWN |

| PCDH19 | ENSG00000165194 | UP |

| PCOLCE2 | ENSG00000163710 | UP |

| PDE4B | ENSG00000184588 | DOWN |

| PHYHD1 | ENSG00000175287 | UP |

| PKIB | ENSG00000135549 | DOWN |

| PLXNA2 | ENSG00000076356 | UP |

| PURPL | ENSG00000250337 | UP |

| PXDN | ENSG00000130508 | UP |

| RBP1 | ENSG00000114115 | DOWN |

| RBPMS | ENSG00000157110 | UP |

| RGS16 | ENSG00000143333 | UP |

| RGS2 | ENSG00000116741 | UP |

| RNF43 | ENSG00000108375 | DOWN |

| RTN4RL1 | ENSG00000185924 | UP |

| RUNX2 | ENSG00000124813 | UP |

| SAMD11 | ENSG00000187634 | UP |

| SERPING1 | ENSG00000149131 | UP |

| SLC16A6 | ENSG00000108932 | UP |

| SLC17A9 | ENSG00000101194 | UP |

| SLC5A5 | ENSG00000105641 | DOWN |

| SLCO3A1 | ENSG00000176463 | UP |

| SNAP25 | ENSG00000132639 | UP |

| SRGAP1 | ENSG00000196935 | DOWN |

| STK39 | ENSG00000198648 | DOWN |

| STYK1 | ENSG00000060140 | DOWN |

| SULF2 | ENSG00000196562 | UP |

| SULT1A4 | ENSG00000213648 | UP |

| SYT13 | ENSG00000019505 | UP |

| SYTL3 | ENSG00000164674 | UP |

| TACSTD2 | ENSG00000184292 | DOWN |

| TLL1 | ENSG00000038295 | UP |

| TMEM154 | ENSG00000170006 | UP |

| TMEM181 | ENSG00000146433 | UP |

| TMEM200A | ENSG00000164484 | DOWN |

| TNFRSF10C | ENSG00000173535 | UP |

| TNFSF18 | ENSG00000120337 | DOWN |

| TRAPPC9 | ENSG00000167632 | DOWN |

| TRHDE | ENSG00000072657 | UP |

| TRPV2 | ENSG00000187688 | UP |

| TULP4 | ENSG00000130338 | UP |

| VGLL3 | ENSG00000206538 | UP |

| VSNL1 | ENSG00000163032 | DOWN |

| WNT5A | ENSG00000114251 | UP |

| ZNF585B | ENSG00000245680 | DOWN |

| ZNF595 | ENSG00000272602 | DOWN |

| ZNF704 | ENSG00000164684 | DOWN |

A total of 125 genes displayed differential expression in LRRC8A KO versus WT cells. 56 genes being down-regulated and 69 up-regulated in LRRC8A KO cells.

Fig. 3. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of down- and up-regulated genes across three principal ontologies.

A The graph provides the enrichment scores from a Gene Ontology analysis focusing on down-regulated genes, categorized into the domains of Biological Processes (BP), Cellular Components (CC), and Molecular Functions (MF). The bars, color-coded as orange for BP, green for CC, and blue for MF, illustrate the degree of each GO term within the studied dataset. Notably, BP terms such as regulation of insulin secretion’ and ‘lipid homeostasis’ show the highest enrichment scores, indicating their significant down-regulation in the genomic profile. B The figure delineates a series of genes with their corresponding log fold changes (logFC), indicating a down-regulation in expression levels. The color-coded segments represent individual genes, while the connecting ribbons illustrate their binding to specific GO terms associated. The GO terms lists include cell-cell junctions, synaptic activity, and binding activities (such as calmodulin and glycosaminoglycan). C The chart depicts the enrichment scores derived from a GO analysis for up-regulated genes. Notably, “calmodulin-dependent protein kinase activity” in the MF category and “insulin secretion” in the BP category exhibit the highest enrichment scores, suggesting significant up-regulation in these functional areas. D The figure draws the genes with their corresponding logFC. GO terms associated with these genes are listed, including those related to cell-cell junctions, synaptic activity, and binding activities (such as calmodulin and glycosaminoglycan).

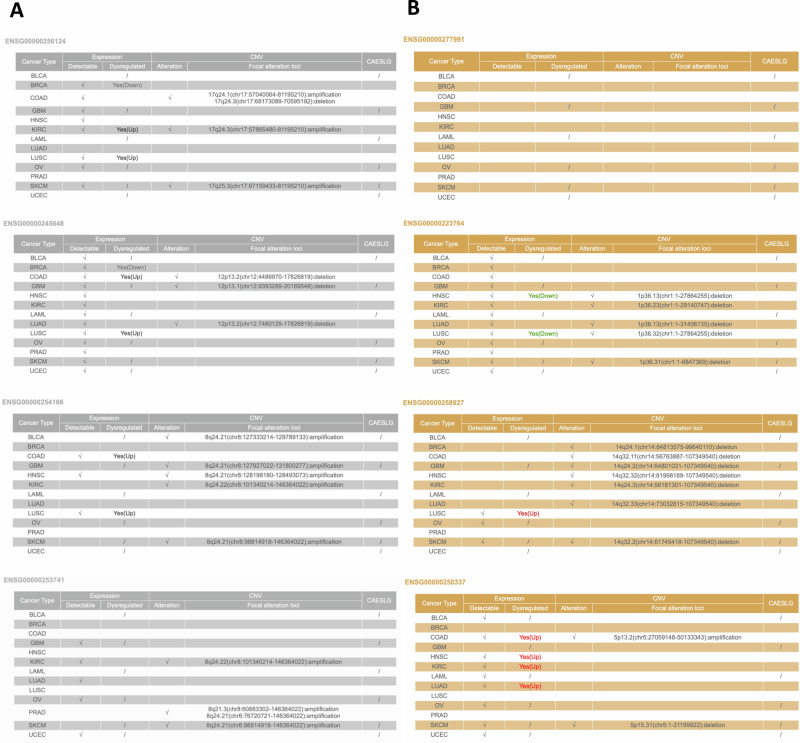

Furthermore, our attention was directed towards long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). Recent research has shown a significant correlation between aberrant expression patterns of lncRNAs and various complex human diseases, particularly cancer. The increasing repertoire of lncRNAs has led to their characterization as either ‘oncogenes’ or ‘tumor suppressors’. Dysregulation of lncRNAs has been linked to the initiation, progression, and metastasis of cancer [40, 41]. The Cancer LncRNome Atlas was used to investigate alterations in individual lncRNAs at transcriptional, genomic, and epigenetic levels in human cancers to identify relevant information (Table 2 and Fig. 4). The observed lncRNAs exhibited varied patterns of regulation across different cancer types, with some showing upregulation and others downregulation (Table 2 and Fig. 4). This differential expression, coupled with their location on the chromosomes as noted in the data, hints at the complex genetic architecture that underlies cancer.

Table 2.

List of lncRNAs.

| Regulation | Ensembl ID | log2 Fold Change | Adj.Pval | Symbol | Chr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down | ENSG00000256124 | −6.55320993004657 | 2.72e−03 | LINC01152 | 17q24.3 |

| Down | ENSG00000245648 | −1.4700236550104 | 1.85e−05 | KLRK1-AS1 | 12p13.2 |

| Down | ENSG00000254166 | −1.4339799975236 | 1.03e−05 | CASC19 | 8q24.21 |

| Down | ENSG00000253741 | −1.07168286754586 | 2.20e−03 | LNCOC1 | 8q24.3 |

| Up | ENSG00000277991 | 4.24840538102438 | 9.66e−05 | 21p11.2 | |

| Up | ENSG00000258927 | 3.31905187015385 | 4.01e−03 | 14q32.13 | |

| Up | ENSG00000223764 | 1.49820395651212 | 3.96e−03 | LINC02593 | 1p36.33 |

| Up | ENSG00000250337 | 1.44062288967738 | 1.34e−03 | PURPL | 5p14.1 |

The expression is evaluated considering LRRC8A-KO vs WT in HCT116.

Fig. 4. Expression Profiles of lncRNAs Across Various Cancer Types.

The tables systematically compare the expression profiles of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) across different cancer types. A and B illustrate, respectively, the downregulated and upregulated lncRNAs in various types of cancers. Each row represents a specific lncRNA, with columns indicating detectability, expression dysregulation, alterations, and the localization of focal alterations within the genome, as identified in the CAESLG database.

Defining the LRRC8A interactome in living cells

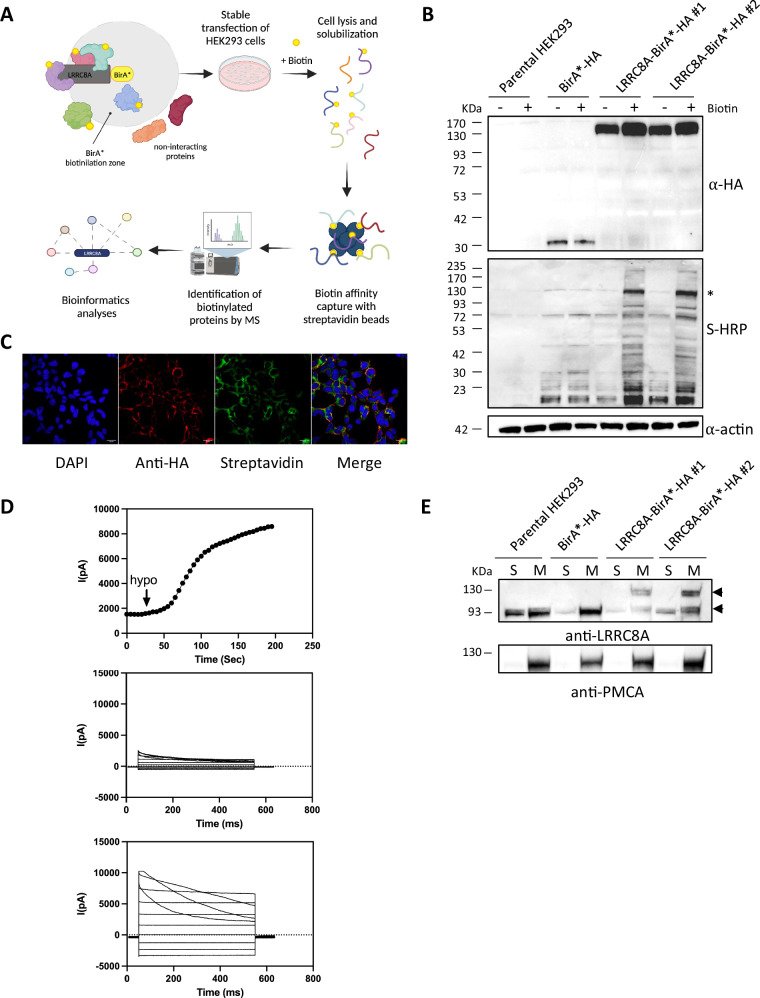

To identify regulators of LRRC8A, we employed the BioID technique (Fig. 5A). WT human LRRC8A was fused with BirA*-HA and HEK293 cell lines stably expressing the LRRC8A-BirA*-HA fusion protein were generated. Stable expression was employed to maximize the formation of VRAC heteromers. The parental cell line and cells expressing solely the BirA* enzyme served as negative and positive controls, respectively. To validate the proper production of the BirA* protein fusion, we performed western blot experiments using Streptavidin-HRP to assess the degree of biotinylation in the presence and absence of exogenous biotin (Fig. 5B). As expected, distinct bands of varying sizes were observed in LRRC8A-BirA* cells in the presence of biotin. Conversely, minimal levels of biotinylation were detected in control lysates, both in the presence and absence of biotin (Fig. 5B). Subsequently, to verify that the genetic fusion of LRRC8A with BirA*-HA did not alter intracellular localization and channel function, we conducted confocal microscopy and patch-clamp experiments (Fig. 5C, D). The presence of BirA*-HA did not impact channel activity (Fig. 5D), consistent with observations for LRRC8A with a C-terminal GFP tag—a protein with a similar molecular weight and steric hindrance to the BirA* enzyme [18]. Fluorescence microscopy confirmed that the fusion protein localized to the plasma membrane similarly to endogenous channels (Fig. 5C) Biotinylation was further confirmed using Alexa Fluor 488 nm-conjugated streptavidin (Fig. 5C). Additionally, western blots confirmed the localization of the fusion protein in membranes (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5. Characterization of cells stably expressing LRRC8A-BioID fusion protein.

A Schematic representation of the BioID technique, a method for exploring protein complexes in live cells [114, 120]. Within the BioID methodology, the target protein is expressed in cells as a fusion with a specialized tagging enzyme, BirA R118G (a promiscuous mutant biotin ligase, hereinafter referred to as BirA*). This enzyme utilizes exogenous biotin to catalyse the formation of biotinoyl-5’-AMP, a highly reactive molecule that biotinylates primary amines, such as the lysine side chain, within a proximity of approximately 10 nm [121]. Subsequently, cells are lysed, and the labeled proteins are subjected to affinity purification, followed by detection through MS. The identification of pertinent biotinylated proteins is then accomplished through quantitative and statistical methodologies B Verification of BirA* activity in cells expressing LRRC8A-BirA*-HA by Western blot. The expression of the LRRC8A-BirA*-HA fusion protein was assessed using an anti-HA antibody in the absence and presence of biotin. BirA* activity in cells expressing LRRC8A-BirA*-HA was assessed by WB using streptavidin-HRP for the detection of biotinylated proteins. Activity was assessed in the presence and absence of biotin (50 μM), using HEK293 cells and cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 MCS-BirA(R118G)-HA (in the blot indicated as BirA*) as controls. Actin was used as a loading control. For each sample, 50 μg of total protein extract was loaded. C Validation of the subcellular localization of the LRRC8A-BirA*-HA protein by immunofluorescence. Nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining; α-HA antibody and Alexa Fluor 586-conjugated red-emitting secondary antibody were used to visualize LRRC8A-BirA*-HA; streptavidin-HRP was used to visualize biotinylated proteins. D Validation of LRRC8A-BirA*-HA protein channel activity by patch clamp: Representative time course of current activation upon perfusion with a hypotonic solution of cells co-expressing the 8A-BirA*-8E heteromers. E Validation of the subcellular localization of the LRRC8A-BirA*-HA protein by Western Blotting. The localization of the LRRC8A-BirA*-HA protein was assessed in the two clones and in HEK293 cells and cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 MCS-BirA(R118G)-HA using the α-LRRC8A antibody. For each sample, 50 μg of protein extract enriched with the cytoplasmic (S) or membrane (M) protein fraction was loaded. The α-PMCA antibody was used to exclude contamination of the S-fraction by proteins from the M-fraction.

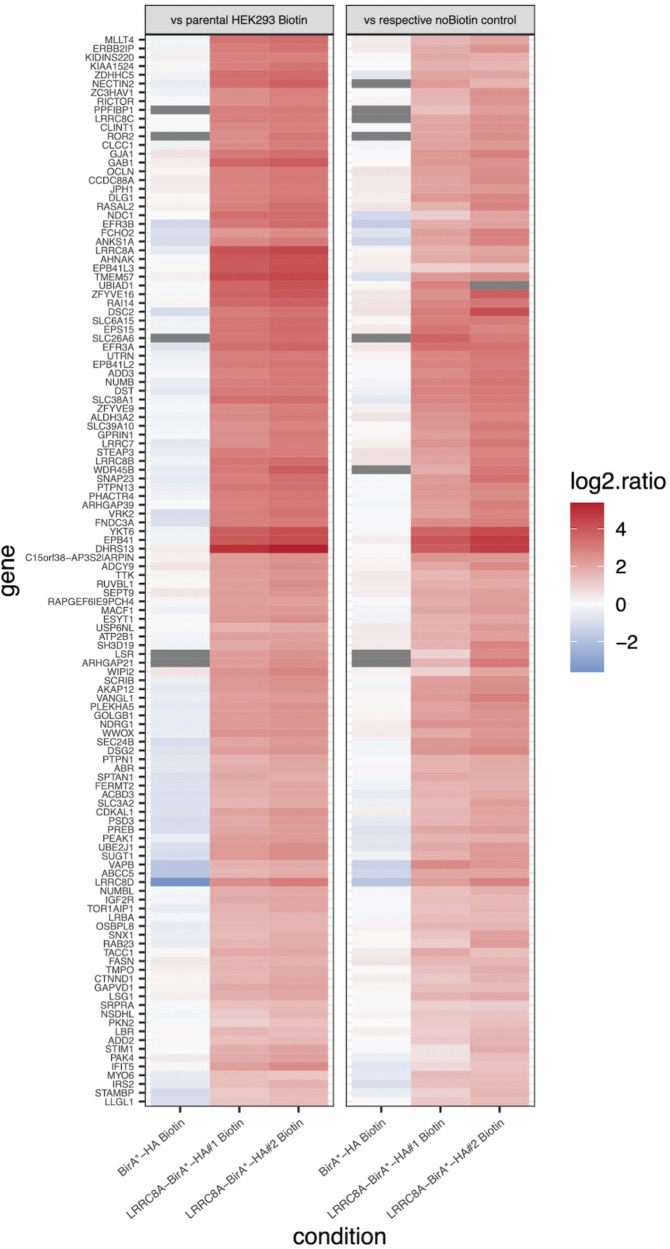

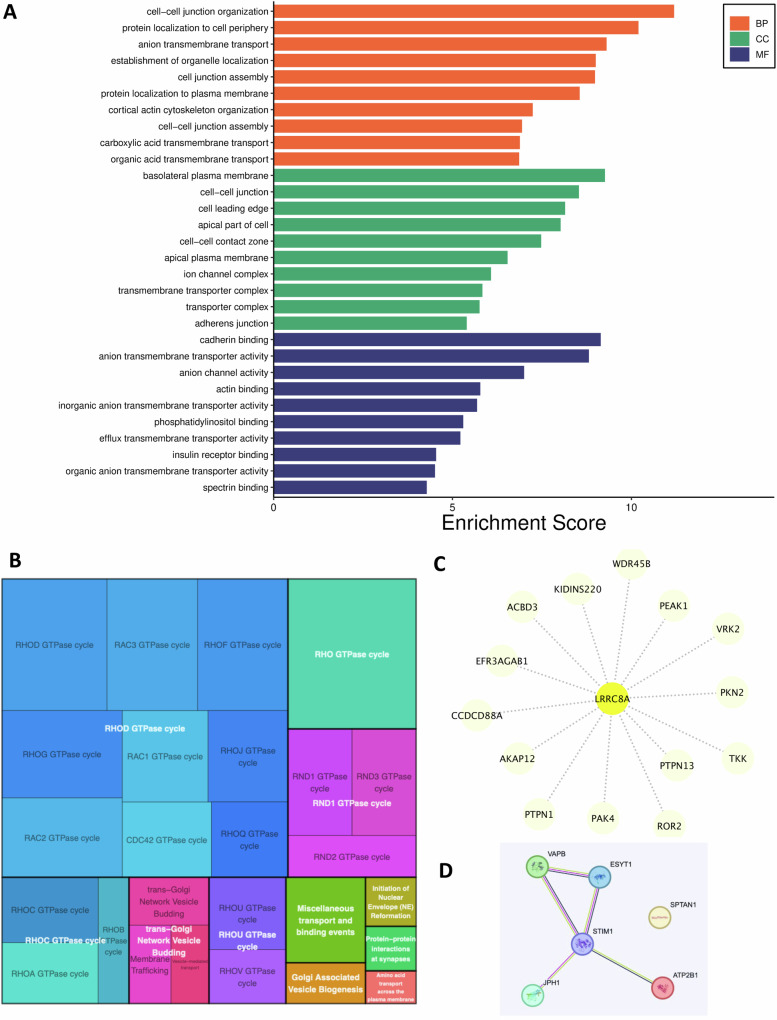

Following the validation of the correct cellular localization and function of LRRC8A-BioID, purified biotinylated proteins were analysed with quantitative mass spectrometry (MS) using tandem mass tag labelling (TMT). The tagged proteins were isolated through streptavidin affinity purification, TMT labelled and analysed by LC-MS/MS. Raw files were analysed using IsobarQuant and Mascot (v2.2.07) (see overview of normalized TMT reporter ion intensities in Figure S1A for an overview of samples). Quantification of individual protein enrichment was determined by comparing their relative abundance in each LRRC8A-BirA* sample with the experimentally paired Venus-BirA* control (no Biotin control, see Volcano Plots in Figure S1B). To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the proximal protein environment surrounding the VRAC complex, a stringent cut-off was applied to the dataset. Only proteins quantified with two unique peptide matches were retained for analysis. Proteins were further tested for differential abundance using a moderated t-test by applying the limma R package. As a significance cut-off we used a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.05 and a fold change (FC) of at least 2-fold. Out of 1227 proteins, we selected 122 enriched hits (around 10% of the total) with a significant up-biotinylation in the comparisons ‘LRRC8A-BirA*-HA#1 Biotin vs LRRC8A-BirA*-HA#1 noBiotin’ or ‘LRRC8A-BirA*-HA#2 Biotin vs LRRC8A-BirA*-HA#2 noBiotin’ (see Volcano Plots in Figure S1B, Fig. 6, Table 3).

Fig. 6. MS results: identification of hits proteins.

Heatmap reporting the log2 fold changes as indicated in the heading (left column ratio against the parental HEK293 Biotin control and right column against the corresponding noBiotin control) for the 122 identified enriched proteins (hits).

Table 3.

List and annotations of hit proteins from BioID analyses.

| Protein | stringID | Annotation |

|---|---|---|

| ABCC5 | 9606.ENSP00000333926 | Multidrug resistance-associated protein 5; Acts as a multispecific organic anion pump which can transport nucleotide analogs; Belongs to the ABC transporter superfamily. ABCC family. Conjugate transporter (TC 3.A.1.208) subfamily |

| ABR | 9606.ENSP00000303909 | Active breakpoint cluster region-related protein; GTPase-activating protein for RAC and CDC42. Promotes the exchange of RAC or CDC42-bound GDP by GTP, thereby activating them; C2 domain containing |

| ACBD3 | 9606.ENSP00000355777 | Acyl-coa binding domain containing 3; Golgi resident protein GCP60; Involved in the maintenance of Golgi structure by interacting with giantin, affecting protein transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Involved in hormone-induced steroid biosynthesis in testicular Leydig cells (By similarity). Recruits PI4KB to the Golgi apparatus membrane; enhances the enzyme activity of PI4KB activity via its membrane recruitment thereby increasing the local concentration of the substrate in the vicinity of the kinase; A-kinase anchoring proteins |

| ADD2 | 9606.ENSP00000264436 | Beta-adducin; Membrane-cytoskeleton-associated protein that promotes the assembly of the spectrin-actin network. Binds to the erythrocyte membrane receptor SLC2A1/GLUT1 and may therefore provide a link between the spectrin cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. Binds to calmodulin. Calmodulin binds preferentially to the beta subunit; Belongs to the aldolase class II family. |

| ADD3 | 9606.ENSP00000348381 | Gamma-adducin; Membrane-cytoskeleton-associated protein that promotes the assembly of the spectrin-actin network. Plays a role in actin filament capping. Binds to calmodulin; Belongs to the aldolase class II family. Adducin subfamily |

| AHNAK | 9606.ENSP00000367263 | Neuroblast differentiation-associated protein AHNAK; May be required for neuronal cell differentiation; PDZ domain containing |

| AKAP12 | 9606.ENSP00000384537 | A-kinase anchor protein 12; Anchoring protein that mediates the subcellular compartmentation of protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC); A-kinase anchoring proteins |

| ALDH3A2 | 9606.ENSP00000345774 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family member a2; Fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase; Catalyzes the oxidation of long-chain aliphatic aldehydes to fatty acids. Active on a variety of saturated and unsaturated aliphatic aldehydes between 6 and 24 carbons in length. Responsible for conversion of the sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) degradation product hexadecenal to hexadecenoic acid |

| ANKS1A | 9606.ENSP00000353518 | Ankyrin repeat and SAM domain-containing protein 1A; Regulator of different signaling pathways. Regulates EPHA8 receptor tyrosine kinase signaling to control cell migration and neurite retraction (By similarity); Ankyrin repeat domain containing |

| ARHGAP21 | 9606.ENSP00000379709 | Rho GTPase-activating protein 21; Functions as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for RHOA and CDC42. Downstream partner of ARF1 which may control Golgi apparatus structure and function. Also required for CTNNA1 recruitment to adherens junctions; PDZ domain containing |

| ARHGAP39 | 9606.ENSP00000366522 | Rho gtpase-activating protein 39; Rho GTPase activating protein 39 |

| ATP2B1 | 9606.ENSP00000392043 | Plasma membrane calcium-transporting ATPase 1; This magnesium-dependent enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of ATP coupled with the transport of calcium out of the cell; ATPases Ca2+ transporting |

| CCDC88A | 9606.ENSP00000338728 | Coiled-coil domain containing 88a; Girdin; Plays a role as a key modulator of the AKT-mTOR signaling pathway controlling the tempo of the process of newborn neurons integration during adult neurogenesis, including correct neuron positioning, dendritic development and synapse formation (By similarity). Enhances phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)- dependent phosphorylation and kinase activity of AKT1/PKB, but does not possess kinase activity itself (By similarity). Phosphorylation of AKT1/PKB thereby induces the phosphorylation of downstream effectors GSK3 and FOXO1/FKHR |

| CDKAL1 | 9606.ENSP00000274695 | Threonylcarbamoyladenosine tRNA methylthiotransferase; Catalyzes the methylthiolation of N6- threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t(6)A), leading to the formation of 2- methylthio-N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (ms(2)t(6)A) at position 37 in tRNAs that read codons beginning with adenine; Belongs to the methylthiotransferase family. CDKAL1 subfamily |

| CLCC1 | 9606.ENSP00000349456 | Chloride channel CLIC-like protein 1; Seems to act as a chloride ion channel; Tetraspan junctional complex superfamily |

| CLINT1 | 9606.ENSP00000429824 | Clathrin interactor 1; Binds to membranes enriched in phosphatidylinositol 4,5- bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2). May have a role in transport via clathrin-coated vesicles from the trans-Golgi network to endosomes. Stimulates clathrin assembly |

| CTNND1 | 9606.ENSP00000382004 | Catenin delta-1; Binds to and inhibits the transcriptional repressor ZBTB33, which may lead to activation of target genes of the Wnt signaling pathway (By similarity). Associates with and regulates the cell adhesion properties of both C-, E- and N-cadherins, being critical for their surface stability. Implicated both in cell transformation by SRC and in ligand-induced receptor signaling through the EGF, PDGF, CSF-1 and ERBB2 receptors. Promotes GLIS2 C-terminal cleavage; Belongs to the beta-catenin family |

| DHRS13 | 9606.ENSP00000368173 | Dehydrogenase/reductase SDR family member 13; Putative oxidoreductase |

| DLG1 | 9606.ENSP00000345731 | Disks large homolog 1; Essential multidomain scaffolding protein required for normal development (By similarity). Recruits channels, receptors and signaling molecules to discrete plasma membrane domains in polarized cells. May play a role in adherens junction assembly, signal transduction, cell proliferation, synaptogenesis and lymphocyte activation. Regulates the excitability of cardiac myocytes by modulating the functional expression of Kv4 channels. Functional regulator of Kv1.5 channel; Belongs to the MAGUK family |

| DSC2 | 9606.ENSP00000280904 | Desmocollin-2; Component of intercellular desmosome junctions. Involved in the interaction of plaque proteins and intermediate filaments mediating cell-cell adhesion. May contribute to epidermal cell positioning by mediating differential adhesiveness between cells that express different isoforms |

| DSG2 | 9606.ENSP00000261590 | Desmoglein-2; Component of intercellular desmosome junctions. Involved in the interaction of plaque proteins and intermediate filaments mediating cell-cell adhesion |

| DST | 9606.ENSP00000307959 | Dystonin; Cytoskeletal linker protein. Acts as an integrator of intermediate filaments, actin and microtubule cytoskeleton networks. Required for anchoring either intermediate filaments to the actin cytoskeleton in neural and muscle cells or keratin- containing intermediate filaments to hemidesmosomes in epithelial cells. The proteins may self-aggregate to form filaments or a two- dimensional mesh. Regulates the organization and stability of the microtubule network of sensory neurons to allow axonal transport. Mediates docking of the dynein/dynactin motor complex to vesicle cargos |

| EFR3A | 9606.ENSP00000254624 | Protein EFR3 homolog A; Component of a complex required to localize phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI4K) to the plasma membrane. The complex acts as a regulator of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PtdIns(4)P) synthesis (Probable). In the complex, EFR3A probably acts as the membrane-anchoring component. Also involved in responsiveness to G-protein-coupled receptors; it is however unclear whether this role is direct or indirect |

| EFR3B | 9606.ENSP00000384081 | Protein EFR3 homolog B; Component of a complex required to localize phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI4K) to the plasma membrane. The complex acts as a regulator of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PtdIns(4)P) synthesis (Probable). In the complex, EFR3B probably acts as the membrane-anchoring component. Also involved in responsiveness to G-protein-coupled receptors; it is however unclear whether this role is direct or indirect; Armadillo-like helical domain containing |

| EPB41 | 9606.ENSP00000345259 | Protein 4.1; Protein 4.1 is a major structural element of the erythrocyte membrane skeleton. It plays a key role in regulating membrane physical properties of mechanical stability and deformability by stabilizing spectrin-actin interaction. Recruits DLG1 to membranes. Required for dynein-dynactin complex and NUMA1 recruitment at the mitotic cell cortex during anaphase |

| EPB41L2 | 9606.ENSP00000338481 | Band 4.1-like protein 2; Required for dynein-dynactin complex and NUMA1 recruitment at the mitotic cell cortex during anaphase; Erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1 |

| EPB41L3 | 9606.ENSP00000343158 | Band 4.1-like protein 3; Tumor suppressor that inhibits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Modulates the activity of protein arginine N- methyltransferases, including PRMT3 and PRMT5; Erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1 |

| EPS15 | 9606.ENSP00000360798 | Epidermal growth factor receptor substrate 15; Involved in cell growth regulation. May be involved in the regulation of mitogenic signals and control of cell proliferation. Involved in the internalization of ligand-inducible receptors of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) type, in particular EGFR. Plays a role in the assembly of clathrin-coated pits (CCPs). Acts as a clathrin adapter required for post-Golgi trafficking. Seems to be involved in CCPs maturation including invagination or budding. Involved in endocytosis of integrin beta- 1 (ITGB1) and transferrin receptor (TFR) |

| ERBB2IP | 9606.ENSP00000426632 | Erbin; Acts as an adapter for the receptor ERBB2, in epithelia. By binding the unphosphorylated ‘Tyr-1248’ of receptor ERBB2, it may contribute to stabilize this unphosphorylated state. Inhibits NOD2-dependent NF-kappa-B signaling and proinflammatory cytokine secretion; Belongs to the LAP (LRR and PDZ) protein family |

| ESYT1 | 9606.ENSP00000267113 | Extended synaptotagmin-1; Binds glycerophospholipids in a barrel-like domain and may play a role in cellular lipid transport (By similarity). Binds calcium (via the C2 domains) and translocates to sites of contact between the endoplasmic reticulum and the cell membrane in response to increased cytosolic calcium levels. Helps tether the endoplasmic reticulum to the cell membrane and promotes the formation of appositions between the endoplasmic reticulum and the cell membrane; Belongs to the extended synaptotagmin family |

| FASN | 9606.ENSP00000304592 | Fatty acid synthase; Fatty acid synthetase catalyzes the formation of long- chain fatty acids from acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA and NADPH. This multifunctional protein has 7 catalytic activities and an acyl carrier protein; Seven-beta-strand methyltransferase motif containing |

| FCHO2 | 9606.ENSP00000393776 | F-BAR domain only protein 2; Functions in an early step of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Has both a membrane binding/bending activity and the ability to recruit proteins essential to the formation of functional clathrin-coated pits. Has a lipid-binding activity with a preference for membranes enriched in phosphatidylserine and phosphoinositides (Pi(4,5) biphosphate) like the plasma membrane. Its membrane-bending activity might be important for the subsequent action of clathrin and adaptors in the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles |

| FERMT2 | 9606.ENSP00000342858 | Fermitin family homolog 2; Scaffolding protein that enhances integrin activation mediated by TLN1 and/or TLN2, but activates integrins only weakly by itself. Binds to membranes enriched in phosphoinositides. Enhances integrin-mediated cell adhesion onto the extracellular matrix and cell spreading; this requires both its ability to interact with integrins and with phospholipid membranes. Required for the assembly of focal adhesions. Participates in the connection between extracellular matrix adhesion sites and the actin cytoskeleton |

| FNDC3A | 9606.ENSP00000441831 | Fibronectin type-III domain-containing protein 3A; Mediates spermatid-Sertoli adhesion during spermatogenesis; Belongs to the FNDC3 family |

| GAB1 | 9606.ENSP00000262995 | GRB2-associated-binding protein 1; Adapter protein that plays a role in intracellular signaling cascades triggered by activated receptor-type kinases. Plays a role in FGFR1 signaling. Probably involved in signaling by the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the insulin receptor (INSR) |

| GAPVD1 | 9606.ENSP00000377664 | GTPase-activating protein and VPS9 domain-containing protein 1; Acts both as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) and a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), and participates in various processes such as endocytosis, insulin receptor internalization or LC2A4/GLUT4 trafficking. Acts as a GEF for the Ras-related protein RAB31 by exchanging bound GDP for free GTP, leading to regulate LC2A4/GLUT4 trafficking. In the absence of insulin, it maintains RAB31 in an active state and promotes a futile cycle between LC2A4/GLUT4 storage vesicles and early endosomes |

| GJA1 | 9606.ENSP00000282561 | Gap junction alpha-1 protein; Gap junction protein that acts as a regulator of bladder capacity. A gap junction consists of a cluster of closely packed pairs of transmembrane channels, the connexons, through which materials of low MW diffuse from one cell to a neighboring cell. May play a critical role in the physiology of hearing by participating in the recycling of potassium to the cochlear endolymph. Negative regulator of bladder functional capacity: acts by enhancing intercellular electrical and chemical transmission |

| GOLGB1 | 9606.ENSP00000377275 | Golgin subfamily B member 1; May participate in forming intercisternal cross-bridges of the Golgi complex |

| GPRIN1 | 9606.ENSP00000305839 | G protein-regulated inducer of neurite outgrowth 1; May be involved in neurite outgrowth |

| IFIT5 | 9606.ENSP00000360860 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 5; Interferon-induced RNA-binding protein involved in the human innate immune response. Has a broad and adaptable RNA structure recognition important for RNA recognition specificity in antiviral defense. Binds precursor and processed tRNAs as well as poly-U-tailed tRNA fragments. Specifically binds single-stranded RNA bearing a 5’-triphosphate group (PPP-RNA), thereby acting as a sensor of viral single-stranded RNAs. |

| IGF2R | 9606.ENSP00000349437 | Cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor; Transport of phosphorylated lysosomal enzymes from the Golgi complex and the cell surface to lysosomes. Lysosomal enzymes bearing phosphomannosyl residues bind specifically to mannose-6- phosphate receptors in the Golgi apparatus and the resulting receptor-ligand complex is transported to an acidic prelyosomal compartment where the low pH mediates the dissociation of the complex. This receptor also binds IGF2. Acts as a positive regulator of T-cell coactivation, by binding DPP4; CD molecules |

| IRS2 | 9606.ENSP00000365016 | Insulin receptor substrate 2; May mediate the control of various cellular processes by insulin; Pleckstrin homology domain containing |

| JPH1 | 9606.ENSP00000344488 | Junctophilin-1; Junctophilins contribute to the formation of junctional membrane complexes (JMCs) which link the plasma membrane with the endoplasmic or sarcoplasmic reticulum in excitable cells. Provides a structural foundation for functional cross-talk between the cell surface and intracellular calcium release channels. JPH1 contributes to the construction of the skeletal muscle triad by linking the t-tubule (transverse-tubule) and SR (sarcoplasmic reticulum) membranes |

| KIAA1524 | 9606.ENSP00000295746 | Cellular inhibitor of pp2a; Protein CIP2A; Oncoprotein that inhibits PP2A and stabilizes MYC in human malignancies. Promotes anchorage-independent cell growth and tumor formation |

| KIDINS220 | 9606.ENSP00000256707 | Ankyrin repeat-rich membrane spanning protein; Kinase D-interacting substrate of 220 kDa; Promotes a prolonged MAP-kinase signaling by neurotrophins through activation of a Rap1-dependent mechanism. Provides a docking site for the CRKL-C3G complex, resulting in Rap1-dependent sustained ERK activation. May play an important role in regulating postsynaptic signal transduction through the syntrophin-mediated localization of receptor tyrosine kinases such as EPHA4. In cooperation with SNTA1 can enhance EPHA4-induced JAK/STAT activation. |

| LBR | 9606.ENSP00000339883 | Delta14-sterol reductase (lamin-B receptor); Lamin-B receptor; Anchors the lamina and the heterochromatin to the inner nuclear membrane; Tudor domain containing |

| LLGL1 | 9606.ENSP00000321537 | LLGL1, scribble cell polarity complex component; Lethal(2) giant larvae protein homolog 1; Cortical cytoskeleton protein found in a complex involved in maintaining cell polarity and epithelial integrity. Involved in the regulation of mitotic spindle orientation, proliferation, differentiation and tissue organization of neuroepithelial cells. Involved in axonogenesis through RAB10 activation thereby regulating vesicular membrane trafficking toward the axonal plasma membrane |

| LRBA | 9606.ENSP00000349629 | Lipopolysaccharide-responsive and beige-like anchor protein; May be involved in coupling signal transduction and vesicle trafficking to enable polarized secretion and/or membrane deposition of immune effector molecules; Armadillo-like helical domain containing |

| LRRC7 | 9606.ENSP00000035383 | Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 7; Required for normal synaptic spine architecture and function. Necessary for DISC1 and GRM5 localization to postsynaptic density complexes and for both N-methyl D-aspartate receptor-dependent and metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long term depression; Belongs to the LAP (LRR and PDZ) protein family |

| LRRC8B | 9606.ENSP00000332674 | Volume-regulated anion channel subunit LRRC8B; Non-essential component of the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC, also named VSOAC channel), an anion channel required to maintain a constant cell volume in response to extracellular or intracellular osmotic changes. The VRAC channel conducts iodide better than chloride and may also conduct organic osmolytes like taurine. Channel activity requires LRRC8A plus at least one other family member (LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D or LRRC8E); channel characteristics depend on the precise subunit composition |

| LRRC8C | 9606.ENSP00000359483 | Volume-regulated anion channel subunit LRRC8C; Non-essential component of the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC, also named VSOAC channel), an anion channel required to maintain a constant cell volume in response to extracellular or intracellular osmotic changes. The VRAC channel conducts iodide better than chloride and may also conduct organic osmolytes like taurine. Channel activity requires LRRC8A plus at least one other family member (LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D or LRRC8E); channel characteristics depend on the precise subunit composition |

| LRRC8D | 9606.ENSP00000338887 | Volume-regulated anion channel subunit LRRC8D; Non-essential component of the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC, also named VSOAC channel), an anion channel required to maintain a constant cell volume in response to extracellular or intracellular osmotic changes. The VRAC channel conducts iodide better than chloride and may also conduct organic osmolytes like taurine. Channel activity requires LRRC8A plus at least one other family member (LRRC8B, LRRC8C, LRRC8D or LRRC8E); channel characteristics depend on the precise subunit composition |

| LSG1 | 9606.ENSP00000265245 | Large subunit GTPase 1 homolog; GTPase required for the XPO1/CRM1-mediated nuclear export of the 60 S ribosomal subunit. Probably acts by mediating the release of NMD3 from the 60 S ribosomal subunit after export into the cytoplasm |

| LSR | 9606.ENSP00000480821 | Lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor; Probable role in the clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein from blood. Binds chylomicrons, LDL and VLDL in presence of free fatty acids and allows their subsequent uptake in the cells (By similarity); Belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily. LISCH7 family |

| MACF1 | 9606.ENSP00000354573 | Microtubule-actin cross-linking factor 1, isoforms 1/2/3/5; Isoform 2: F-actin-binding protein which plays a role in cross-linking actin to other cytoskeletal proteins and also binds to microtubules. Plays an important role in ERBB2-dependent stabilization of microtubules at the cell cortex. Acts as a positive regulator of Wnt receptor signaling pathway and is involved in the translocation of AXIN1 and its associated complex (composed of APC, CTNNB1 and GSK3B) from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane (By similarity). |

| MLLT4 | 9606.ENSP00000375960 | Afadin; Belongs to an adhesion system, probably together with the E-cadherin-catenin system, which plays a role in the organization of homotypic, interneuronal and heterotypic cell-cell adherens junctions (AJs). Nectin- and actin-filament-binding protein that connects nectin to the actin cytoskeleton |

| MYO6 | 9606.ENSP00000358994 | Unconventional myosin-VI; Myosins are actin-based motor molecules with ATPase activity. Unconventional myosins serve in intracellular movements. Myosin 6 is a reverse-direction motor protein that moves towards the minus-end of actin filaments. Has slow rate of actin-activated ADP release due to weak ATP binding. Functions in a variety of intracellular processes such as vesicular membrane trafficking and cell migration. Required for the structural integrity of the Golgi apparatus via the p53-dependent pro-survival pathway. |

| NDC1 | 9606.ENSP00000360483 | NDC1 transmembrane nucleoporin; Nucleoporin NDC1; Component of the nuclear pore complex (NPC), which plays a key role in de novo assembly and insertion of NPC in the nuclear envelope. Required for NPC and nuclear envelope assembly, possibly by forming a link between the nuclear envelope membrane and soluble nucleoporins, thereby anchoring the NPC in the membrane |

| NDRG1 | 9606.ENSP00000404854 | N-myc downstream regulated 1; Protein NDRG1; Stress-responsive protein involved in hormone responses, cell growth, and differentiation. Acts as a tumor suppressor in many cell types. Necessary but not sufficient for p53/TP53- mediated caspase activation and apoptosis. Has a role in cell trafficking, notably of the Schwann cell, and is necessary for the maintenance and development of the peripheral nerve myelin sheath. Required for vesicular recycling of CDH1 and TF. May also function in lipid trafficking. Protects cells from spindle disruption damage. |

| NECTIN2 | 9606.ENSP00000252483 | Nectin-2; Modulator of T-cell signaling. Can be either a costimulator of T-cell function, or a coinhibitor, depending on the receptor it binds to. Upon binding to CD226, stimulates T-cell proliferation and cytokine production, including that of IL2, IL5, IL10, IL13, and IFNG. Upon interaction with PVRIG, inhibits T-cell proliferation. These interactions are competitive. Probable cell adhesion protein; Belongs to the nectin family |

| NSDHL | 9606.ENSP00000359297 | Sterol-4-alpha-carboxylate 3-dehydrogenase, decarboxylating; Involved in the sequential removal of two C-4 methyl groups in post-squalene cholesterol biosynthesis; Short chain dehydrogenase/reductase superfamily |

| NUMB | 9606.ENSP00000451300 | Numb, endocytic adaptor protein; Protein numb homolog; Plays a role in the process of neurogenesis. Required throughout embryonic neurogenesis to maintain neural progenitor cells, also called radial glial cells (RGCs), by allowing their daughter cells to choose progenitor over neuronal cell fate. Not required for the proliferation of neural progenitor cells before the onset of neurogenesis. Also involved postnatally in the subventricular zone (SVZ) neurogenesis by regulating SVZ neuroblasts survival and ependymal wall integrity. May also mediate local repair of brain ventricular wall damage |

| NUMBL | 9606.ENSP00000252891 | Numb-like protein; Plays a role in the process of neurogenesis. Required throughout embryonic neurogenesis to maintain neural progenitor cells, also called radial glial cells (RGCs), by allowing their daughter cells to choose progenitor over neuronal cell fate. Not required for the proliferation of neural progenitor cells before the onset of embryonic neurogenesis. Also required postnatally in the subventricular zone (SVZ) neurogenesis by regulating SVZ neuroblasts survival and ependymal wall integrity. Negative regulator of NF-kappa-B signaling pathway. The inhibition of NF- kappa-B a […] |

| OCLN | 9606.ENSP00000347379 | Occludin; May play a role in the formation and regulation of the tight junction (TJ) paracellular permeability barrier. It is able to induce adhesion when expressed in cells lacking tight junctions; Protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunits |

| OSBPL8 | 9606.ENSP00000261183 | Oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 8; Lipid transporter involved in lipid countertransport between the endoplasmic reticulum and the plasma membrane: specifically exchanges phosphatidylserine with phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P), delivering phosphatidylserine to the plasma membrane in exchange for PI4P, which is degraded by the SAC1/SACM1L phosphatase in the endoplasmic reticulum. Binds phosphatidylserine and PI4P in a mutually exclusive manner. Binds oxysterol, 25- hydroxycholesterol and cholesterol; Belongs to the OSBP family |

| PAK4 | 9606.ENSP00000469413 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PAK 4; Serine/threonine protein kinase that plays a role in a variety of different signaling pathways including cytoskeleton regulation, cell migration, growth, proliferation or cell survival. Activation by various effectors including growth factor receptors or active CDC42 and RAC1 results in a conformational change and a subsequent autophosphorylation on several serine and/or threonine residues. Phosphorylates and inactivates the protein phosphatase SSH1, leading to increased inhibitory phosphorylation of the actin binding/depolymerizing factor cofilin |

| PEAK1 | 9606.ENSP00000452796 | Pseudopodium-enriched atypical kinase 1; Tyrosine kinase that may play a role in cell spreading and migration on fibronectin. May directly or indirectly affect phosphorylation levels of cytoskeleton-associated proteins MAPK1/ERK and PXN |

| PHACTR4 | 9606.ENSP00000362942 | Phosphatase and actin regulator 4; Regulator of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) required for neural tube and optic fissure closure, and enteric neural crest cell (ENCCs) migration during development. Acts as an activator of PP1 by interacting with PPP1CA and preventing phosphorylation of PPP1CA at ‘Thr-320’. During neural tube closure, localizes to the ventral neural tube and activates PP1, leading to down-regulate cell proliferation within cranial neural tissue and the neural retina. Also acts as a regulator of migration of enteric neural crest cells (ENCCs) by activating PP1 |

| PKN2 | 9606.ENSP00000359552 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase N2; PKC-related serine/threonine-protein kinase and Rho/Rac effector protein that participates in specific signal transduction responses in the cell. Plays a role in the regulation of cell cycle progression, actin cytoskeleton assembly, cell migration, cell adhesion, tumor cell invasion and transcription activation signaling processes. Phosphorylates CTTN in hyaluronan-induced astrocytes and hence decreases CTTN ability to associate with filamentous actin. Phosphorylates HDAC5, therefore lead to impair HDAC5 import. |

| PLEKHA5 | 9606.ENSP00000404296 | Pleckstrin homology domain-containing family a member 5; Pleckstrin homology domain containing A5 |

| PPFIBP1 | 9606.ENSP00000314724 | Ppfia binding protein 1; Liprin-beta-1; May regulate the disassembly of focal adhesions. Did not bind receptor-like tyrosine phosphatases type 2 A; Sterile alpha motif domain containing |

| PREB | 9606.ENSP00000260643 | Prolactin regulatory element-binding protein; Guanine nucleotide exchange factor that specifically activates the small GTPase SAR1B. Mediates the recruitement of SAR1B and other COPII coat components to endoplasmic reticulum membranes and is therefore required for the formation of COPII transport vesicles from the ER; WD repeat domain containing |

| PSD3 | 9606.ENSP00000324127 | PH and SEC7 domain-containing protein 3; Guanine nucleotide exchange factor for ARF6; Pleckstrin homology domain containing |

| PTPN1 | 9606.ENSP00000360683 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 1; Tyrosine-protein phosphatase which acts as a regulator of endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Mediates dephosphorylation of EIF2AK3/PERK; inactivating the protein kinase activity of EIF2AK3/PERK. May play an important role in CKII- and p60c-src-induced signal transduction cascades. May regulate the EFNA5-EPHA3 signaling pathway which modulates cell reorganization and cell-cell repulsion. May also regulate the hepatocyte growth factor receptor signaling pathway through dephosphorylation of MET |

| PTPN13 | 9606.ENSP00000394794 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 13; Tyrosine phosphatase which regulates negatively FAS- induced apoptosis and NGFR-mediated pro-apoptotic signaling. May regulate phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling through dephosphorylation of PIK3R2; FERM domain containing |

| RAB23 | 9606.ENSP00000417610 | RAB23, member RAS oncogene family; Ras-related protein Rab-23; The small GTPases Rab are key regulators of intracellular membrane trafficking, from the formation of transport vesicles to their fusion with membranes. Rabs cycle between an inactive GDP-bound form and an active GTP-bound form that is able to recruit to membranes different set of downstream effectors directly responsible for vesicle formation, movement, tethering and fusion. Together with SUFU, prevents nuclear import of GLI1, and thereby inhibits GLI1 transcription factor activity. |

| RAI14 | 9606.ENSP00000427123 | Retinoic acid induced 14; Ankycorbin; Plays a role in actin regulation at the ectoplasmic specialization, a type of cell junction specific to testis. Important for establishment of sperm polarity and normal spermatid adhesion. May also promote integrity of Sertoli cell tight junctions at the blood-testis barrier; Ankyrin repeat domain containing |

| RAPGEF6 | 9606.ENSP00000296859 | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor 6; Guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Rap1A, Rap2A and M-Ras GTPases. Does not interact with cAMP; PDZ domain containing |

| RASAL2 | 9606.ENSP00000356621 | Ras GTPase-activating protein nGAP; Inhibitory regulator of the Ras-cyclic AMP pathway; C2 and RasGAP domain containing |

| RICTOR | 9606.ENSP00000296782 | Rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR; Subunit of mTORC2, which regulates cell growth and survival in response to hormonal signals. mTORC2 is activated by growth factors, but, in contrast to mTORC1, seems to be nutrient- insensitive. mTORC2 seems to function upstream of Rho GTPases to regulate the actin cytoskeleton, probably by activating one or more Rho-type guanine nucleotide exchange factors. mTORC2 promotes the serum-induced formation of stress-fibers or F-actin. mTORC2 plays a critical role in AKT1 ‘ |

| ROR2 | 9606.ENSP00000364860 | Tyrosine-protein kinase transmembrane receptor ROR2; Tyrosine-protein kinase receptor which may be involved in the early formation of the chondrocytes. It seems to be required for cartilage and growth plate development (By similarity). Phosphorylates YWHAB, leading to induction of osteogenesis and bone formation. In contrast, has also been shown to have very little tyrosine kinase activity in vitro. May act as a receptor for wnt ligand WNT5A which may result in the inhibition of WNT3A-mediated signaling; I-set domain containing |

| RUVBL1 | 9606.ENSP00000318297 | RuvB-like 1; May be able to bind plasminogen at cell surface and enhance plasminogen activation; AAA ATPases |

| SCRIB | 9606.ENSP00000349486 | Protein scribble homolog; Scaffold protein involved in different aspects of polarized cells differentiation regulating epithelial and neuronal morphogenesis. Most probably functions in the establishment of apico-basal cell polarity. May function in cell proliferation regulating progression from G1 to S phase and as a positive regulator of apoptosis for instance during acinar morphogenesis of the mammary epithelium. May also function in cell migration and adhesion and hence regulate cell invasion through MAPK signaling. May play a role in exocytosis and in the targeting synaptic vesicle |

| SEC24B | 9606.ENSP00000428564 | Protein transport protein Sec24B; Component of the coat protein complex II (COPII) which promotes the formation of transport vesicles from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The coat has two main functions, the physical deformation of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane into vesicles and the selection of cargo molecules for their transport to the Golgi complex. Plays a central role in cargo selection within the COPII complex and together with SEC24A may have a different specificity compared to SEC24C and SEC24D. May package preferentially cargos with cytoplasmic DxE or LxxLE motifs |

| SEPT9 | 9606.ENSP00000391249 | Septin-9; Filament-forming cytoskeletal GTPase (By similarity). May play a role in cytokinesis (Potential). May play a role in the internalization of 2 intracellular microbial pathogens. Belongs to the TRAFAC class TrmE-Era-EngA-EngB-Septin- like GTPase superfamily. Septin GTPase family |

| SH3D19 | 9606.ENSP00000302913 | SH3 domain-containing protein 19; May play a role in regulating A disintegrin and metalloproteases (ADAMs) in the signaling of EGFR-ligand shedding. May be involved in suppression of Ras-induced cellular transformation and Ras-mediated activation of ELK1. Plays a role in the regulation of cell morphology and cytoskeletal organization |

| SLC26A6 | 9606.ENSP00000378920 | Solute carrier family 26 member 6; Apical membrane anion-exchanger with wide epithelial distribution that plays a role as a component of the pH buffering system for maintaining acid-base homeostasis. Acts as a versatile DIDS-sensitive inorganic and organic anion transporter that mediates the uptake of monovalent anions like chloride, bicarbonate, formate and hydroxyl ion and divalent anions like sulfate and oxalate. Function in multiple exchange modes involving pairs of these anions |

| SLC38A1 | 9606.ENSP00000449756 | Sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter 1; Functions as a sodium-dependent amino acid transporter. Mediates the saturable, pH-sensitive and electrogenic cotransport of glutamine and sodium ions with a stoichiometry of 1:1. May also transport small zwitterionic and aliphatic amino acids with a lower affinity. May supply glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons with glutamine which is required for the synthesis of the neurotransmitters glutamate and GABA; Solute carriers |

| SLC39A10 | 9606.ENSP00000386766 | Solute carrier family 39 (zinc transporter), member 10; Zinc transporter ZIP10; May act as a zinc-influx transporter; Belongs to the ZIP transporter (TC 2.A.5) family |

| SLC3A2 | 9606.ENSP00000367123 | 4F2 cell-surface antigen heavy chain; Required for the function of light chain amino-acid transporters. Involved in sodium-independent, high-affinity transport of large neutral amino acids such as phenylalanine, tyrosine, leucine, arginine and tryptophan. Involved in guiding and targeting of LAT1 and LAT2 to the plasma membrane. When associated with SLC7A6 or SLC7A7 acts as an arginine/glutamine exchanger, following an antiport mechanism for amino acid transport, influencing arginine release in exchange for extracellular amino acids. |

| SLC6A15 | 9606.ENSP00000266682 | Sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter B(0)AT2; Functions as a sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter. Exhibits preference for the branched-chain amino acids, particularly leucine, valine and isoleucine and methionine. Mediates the saturable, pH-sensitive and electrogenic cotransport of proline and sodium ions with a stoichiometry of 1:1. May have a role as transporter for neurotransmitter precursors into neurons. In contrast to other members of the neurotransmitter transporter family, does not appear to be chloride-dependent; Solute carriers |

| SNAP23 | 9606.ENSP00000249647 | Synaptosomal-associated protein 23; Essential component of the high affinity receptor for the general membrane fusion machinery and an important regulator of transport vesicle docking and fusion; Belongs to the SNAP-25 family |

| SNX1 | 9606.ENSP00000261889 | Sorting nexin-1; Involved in several stages of intracellular trafficking. Interacts with membranes containing phosphatidylinositol 3- phosphate (PtdIns(3 P)) or phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(3,5)P2). Acts in part as component of the retromer membrane-deforming SNX-BAR subcomplex. The SNX-BAR retromer mediates retrograde transport of cargo proteins from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and is involved in endosome-to-plasma membrane transport for cargo protein recycling. The SNX-BAR subcomplex functions to deform the donor membrane into a tubular profile |

| SPTAN1 | 9606.ENSP00000361824 | Spectrin alpha chain, non-erythrocytic 1; Fodrin, which seems to be involved in secretion, interacts with calmodulin in a calcium-dependent manner and is thus candidate for the calcium-dependent movement of the cytoskeleton at the membrane; EF-hand domain containing |

| SRPRA | 9606.ENSP00000328023 | Signal recognition particle receptor subunit alpha; Component of the SRP (signal recognition particle) receptor. Ensures, in conjunction with the signal recognition particle, the correct targeting of the nascent secretory proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane system |

| STAMBP | 9606.ENSP00000377633 | STAM-binding protein; Zinc metalloprotease that specifically cleaves ‘Lys-63’- linked polyubiquitin chains. Does not cleave ‘Lys-48’-linked polyubiquitin chains (By similarity). Plays a role in signal transduction for cell growth and MYC induction mediated by IL-2 and GM-CSF. Potentiates BMP (bone morphogenetic protein) signaling by antagonizing the inhibitory action of SMAD6 and SMAD7. Has a key role in regulation of cell surface receptor-mediated endocytosis and ubiquitin-dependent sorting of receptors to lysosomes. Endosomal localization of STAMBP is required for efficient EGFR degradation |

| STEAP3 | 9606.ENSP00000376822 | Metalloreductase STEAP3; Endosomal ferrireductase required for efficient transferrin-dependent iron uptake in erythroid cells. Participates in erythroid iron homeostasis by reducing Fe(3 + ) to Fe(2 + ). Can also reduce of Cu(2 + ) to Cu(1 + ), suggesting that it participates in copper homeostasis. Uses NADP(+) as acceptor. May play a role downstream of p53/TP53 to interface apoptosis and cell cycle progression. Indirectly involved in exosome secretion by facilitating the secretion of proteins such as TCTP; STEAP family |

| STIM1 | 9606.ENSP00000478059 | Stromal interaction molecule 1; Plays a role in mediating store-operated Ca(2 + ) entry (SOCE), a Ca(2 + ) influx following depletion of intracellular Ca(2 + ) stores. Acts as Ca(2 + ) sensor in the endoplasmic reticulum via its EF-hand domain. Upon Ca(2 + ) depletion, translocates from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane where it activates the Ca(2 + ) release-activated Ca(2 + ) (CRAC) channel subunit ORAI1. Involved in enamel formation. Activated following interaction with STIMATE, leading to promote STIM1 conformational switch; Sterile alpha motif domain containing |

| SUGT1 | 9606.ENSP00000367208 | SGT1 homolog, MIS12 kinetochore complex assembly cochaperone; Protein SGT1 homolog; May play a role in ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of target proteins |

| TACC1 | 9606.ENSP00000321703 | Transforming acidic coiled-coil-containing protein 1; Likely involved in the processes that promote cell division prior to the formation of differentiated tissues |

| TMEM57 | 9606.ENSP00000363463 | Macoilin 1; Plays a role in the regulation of neuronal activity |

| TMPO | 9606.ENSP00000266732 | Lamina-associated polypeptide 2, isoform alpha; May be involved in the structural organization of the nucleus and in the post-mitotic nuclear assembly. Plays an important role, together with LMNA, in the nuclear anchorage of RB1; Belongs to the LEM family |

| TOR1AIP1 | 9606.ENSP00000435365 | Torsin-1A-interacting protein 1; Required for nuclear membrane integrity. Induces TOR1A and TOR1B ATPase activity and is required for their location on the nuclear membrane. Binds to A- and B-type lamins. Possible role in membrane attachment and assembly of the nuclear lamina |

| TTK | 9606.ENSP00000358813 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase ttk/mps1; Dual specificity protein kinase TTK; Phosphorylates proteins on serine, threonine, and tyrosine. Probably associated with cell proliferation. Essential for chromosome alignment by enhancing AURKB activity (via direct CDCA8 phosphorylation) at the centromere, and for the mitotic checkpoint |