Abstract

Academic Abstract

Integrative theorizing is needed to advance our understanding of the relationship between where a person lives and their mental health. To this end, we introduce a social identity model that provides an integrated explanation of the ways in which social-psychological processes mediate and moderate the links between neighborhood and mental health. In developing this model, we first review existing models that are derived primarily from a resource-availability perspective informed by research in social epidemiology, health geography, and urban sociology. Building on these, the social identity model implicates neighborhood identification in four key pathways between residents’ local environment and their mental health. We review a wealth of recent research that supports this model and which speaks to its capacity to integrate and extend insights from established models. We also explore the implications of the social identity approach for policy and intervention.

Public Abstract

We need to understand the connection between where people live and their mental health better than we do. This article helps us do this by presenting an integrated model of the way that social and psychological factors affect the relationship between someone’s neighborhood and their mental health. This model builds on insights from social epidemiology, health geography, and urban sociology. Its distinct and novel contribution is to point to the importance of four pathways through which neighborhood identification shapes residents’ mental health. A large body of recent research supports this model and highlights its potential to integrate and expand upon existing theories. We also discuss how our model can inform policies and interventions that seek to improve mental health outcomes in communities.

Keywords: community, neighborhood, social identification, social cohesion, mental health, wellbeing

Introduction

A vast body of multidisciplinary research supports the idea that there is a relationship between where people live and their mental health. More specifically, there is evidence that people who live in relatively disadvantaged or “resource-scarce” neighborhoods have worse mental health than those who live in neighborhoods that are advantaged or “resource-abundant” (Cruwys et al., 2022a; D. Kim, 2008; Mair et al., 2008). Indeed, neighborhood disadvantage has been shown to have a negative (and long-term) effect on a wide range of individual mental health outcomes, and these effects remain significant after controlling for an array of demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, socioeconomic status [SES], and marital status). For example, studies have found that the structural features of disadvantaged neighborhoods are associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety (Julien et al., 2012; Remes et al., 2017) as well as an increased incidence of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (March et al., 2008). These structural features include the neighborhood’s socioeconomic status, social composition, and physical and environmental characteristics (e.g., pollution, access to social infrastructure, amenities, and services) that are typically measured using “objective” aggregated census and geospatial data. Research suggests that subjective perceptions of the social and physical neighborhood environment (assessed as individual-level and aggregated neighborhood-level variables) mediate the relationship between objective neighborhood characteristics and mental health outcomes (Kawachi & Subramanian, 2018; Mohnen et al., 2015). However, there are mixed views about how residents’ perceptions relate to a neighborhood’s structural features, and integrating these perspectives is the central goal—and the primary novel contribution—of the present review.

Previous research has demonstrated the importance of neighborhood factors for a wide range of mental health outcomes. However, there are few analyses of when and how these effects arise (van Ham et al., 2013). In this regard, much of the existing literature has investigated whether the availability of resources or the absence or presence of a particular neighborhood characteristic (e.g., density, greenspace) might account for a specific mental health outcome. However, scholars have noted that a sole focus on addressing questions such as whether or not population density is bad for mental health, has been detrimental to theoretical advancements that are needed to allow researchers to understand the mechanisms and causal pathways that link neighborhood and mental health (Sharkey & Faber, 2014). For example, when and why might neighborhood density matter for mental health? Why do some residents perceive a crowded neighborhood more positively than others? Might some residents come to see a crowded neighborhood as giving them access to resources, in ways that are beneficial for mental health? The lack of answers to such questions has led scholars to characterize the link between the neighborhood and mental health as a “black box” (van Ham & Manley, 2012) in which there is a range of more or less reliable associations between neighborhood features and mental health, but no accounts as to when, how, or why these arise. In addressing this significant gap in the field, this review has five key aims.

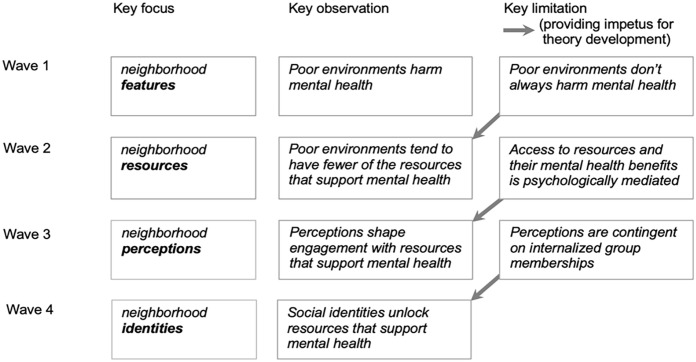

First, we identify key neighborhood factors that are linked to mental health, as revealed by research in fields such as social epidemiology, health geography, and urban sociology. Second, we review and critique the dominant models that have emerged to account for these patterns. In particular, we conclude that there is a need to move beyond (a) exposure models which conceptualize neighborhood effects as arising from independent features of neighborhoods to which residents are assumed to be uniformly exposed, and (b) contingency models which see these effects as the product of an interaction between these socio-spatial features and “demographic” factors that increase subpopulation vulnerability (e.g., income, age). Third, we present the research on two “psychosocial” mediators through which the features of the neighborhood context affect resident mental health. We propose that the heterogeneity of the evidence for perceived social cohesion and perceived environment quality as mediating mechanisms suggests the presence of a psychological moderator (i.e., social identification with one’s neighborhood). Fourth, we build on this critique by pointing to the importance of social-psychological processes—particularly, social identification—in accounting for variability in research findings on the link between neighborhood features and mental health outcomes. Here we note that prevailing models neglect the fact that a neighborhood is a spatially defined social grouping of people that can be internalized into a person’s sense of self (e.g., as residents of a given community; e.g., “us Chelsea residents,” “us Grenfell residents”; Waine & Chapman, 2022) in ways that have an impact on their mental health. We make the case to expand the purview of the resource-availability perspective by including a conceptualization of the neighborhood as a social identity. Finally, fifth, we specify four pathways via which neighborhood identification might underpin the relationship between neighborhood and mental health. Together, this novel framework argues that what it means to be a member of a given neighborhood—as captured by a person’s degree of social identification with other residents—has an important bearing on their mental health and can explain when neighborhoods matter as well as how and why they have an impact on mental health.

Positionality Statement, Citations Statement, Constraints on Generality

Like most other researchers who have studied the links between where people live and their mental health (Baffoe & Kintrea, 2022), we are fortunate to live in affluent and privileged communities in a Westernized, democratic, and industrialized country. Much of the research that feeds into this review has also been conducted by similar researchers in similar communities and countries—in particular, by social identity researchers in Australia and the United Kingdom. At the same time, though, as we will see, many of the researchers on whose work we draw have diverse lived experiences and many have gone to some length to collect data and test theory in communities and countries that are neither Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, nor Democratic. In this review, we endeavor to be as inclusive of this work as possible and to reflect on the implications of our theorizing for people residing in a wide range of neighborhoods and communities (a goal that was greatly helped by the contributions of three anonymous reviewers). In particular, we are keen to try to understand the world (and its implications for mental health) from the position of those who are members of such communities rather than to do so from the perspective of outsiders. That is, we are interested in exploring—and doing justice to—people’s subjectively apprehended social realities, rather than in identifying ways in which their cognitions and perceptions depart from some notionally objective set of norms and standards. For example, we are interested in the meaning that a neighborhood has for residents themselves rather than in benchmarking this against the views of expert outgroups (Rivlin, 1987). Indeed, this is the goal of the social identity approach more generally, and we would argue that the better we are able to do this, the better our theorizing will be (Oakes, 1994; Reicher et al., 2010).

Current Understanding of the Link Between Neighborhood and Mental Health

The relationship between where people live and their mental health has long been a topic of fascination for researchers and practitioners in various fields (e.g., medicine, urban planning, and sociology). Indeed, the first systematic investigation of how place relates to mental health was reported more than 80 years ago by the Chicago-based urban sociologists Robert Faris and Warren Dunham (1939) in pioneering research that sought to clarify the existence and nature of this relationship through the process of “ecological mapping.” This culminated in their landmark text Mental Disorders in Urban Areas which pointed to an unusually high incidence of mental health disorders in neighborhoods that were characterized by low SES and dilapidated housing conditions. Moreover, this mapping process identified geographical links between where people lived in a city and particular kinds of chronic mental health conditions. For example, people living with schizophrenia were clustered mainly in the deprived urban center, whereas those with manic depression lived in both peripheral and central locations. Significantly too, this study changed the discourse around the etiology of mental illness by highlighting the importance of environmental determinants of mental health over and above biological ones (Bloom, 2002).

William J. Wilson’s (1987) book, The Truly Disadvantaged, extended this work on ecological mapping and reignited interest in the effects of poverty on health (both physical and mental) while also pointing to the vital role of neighborhoods in this relationship. In particular, Wilson’s analysis of the relationship between poverty and race in the United States showed that post-industrial economic shifts (e.g., associated with the loss of manufacturing jobs) and suburbanization (particularly of working- and middle-class African-Americans) contributed to the deterioration of the social and physical fabric of inner city areas (e.g., in Detroit, Chicago, and New York). In this widely cited work, Wilson (1987, p. 3) described a “ghetto-underclass” that is over-represented by African Americans who are geographically concentrated in urban areas and isolated from the working/middle classes. Among other ideas, Wilson proposed that this pattern of socio-spatial segregation meant that residents who lived in high-poverty communities lacked access to successful role models and social networks that might give them the resources they needed to get ahead in life.

Accordingly, Wilson (1987) hypothesized that being poor and residing in a low-poverty neighborhood would be less damaging to a person’s welfare than being poor and residing in a high-poverty neighborhood. Specifically, he argued that poor people who lived in high-poverty neighborhoods would do worse than their counterparts in low-poverty neighborhoods because they had access to fewer key resources (e.g., information, jobs, and services). An important contribution of this analysis was to shift policymakers’ attention away from the mind-set that “poor people” live in poverty as a result of their individual behaviors (e.g., teen pregnancy, substance abuse) by pointing instead to the important role played by neighborhood disadvantage—which is outside individual control (Small & Newman, 2005).

Building on these two seminal works, the effect of the local neighborhood context on mental health has subsequently been interrogated extensively by researchers in a range of different fields (e.g., public health, epidemiology, and health geography). In the last 20 to 30 years, much of this interrogation has focused on establishing the different kinds of resources and opportunities that residents can access in their local community and specifying the direct link between these and mental health-related outcomes (Diez Roux & Mair, 2010). This research has typically used a multilevel ecological framework to explore the impact of neighborhood context on individual mental health by controlling for individual-level confounders (e.g., personal SES; Arcaya et al., 2016). The framework suggests that SES can exert its impact on mental health at multiple levels of a person’s ecology (i.e., such that mental health is associated with greater personal, neighborhood, regional, and societal wealth). This, in turn, suggests that no single-level factor can fully explain a person’s mental health. For example, the framework views anxiety as the outcome of interactions between factors that operate at multiple levels—including biological sex (an individual-level factor), neighborhood SES (a group-level factor), and the state of the economy (a societal-level factor).

The Resource-Availability Perspective

The research linking neighborhood and mental health reviewed above is premised on the idea that a person’s mental health outcomes are shaped not just by individual factors (e.g., their personality and biology) but also by their social and physical context. A second assumption is that inequalities in both physical and mental health have a spatial dimension that reflects the uneven distribution of resources. The resource–availability perspective incorporates both assumptions and argues that living in disadvantaged, high-poverty neighborhoods brings with it structural constraints associated with access to fewer resources and opportunities (Galster, 2012; Miltenburg & van der Meer, 2018). These neighborhood-level constraints include high levels of poverty, crime, and domestic violence as well as heavy traffic conditions, noise pollution, the presence of vandalism, and poor-quality housing. Each of these (“stress-inducing”) social and physical features has been associated with mental ill-health (e.g., Jivraj et al., 2020). In contrast, the resources that are typically more available in advantaged neighborhoods (e.g., green spaces, high-quality housing, pedestrian-friendly streets, and public transport access) are generally associated with better mental health (Nuñez-Gonzalez et al., 2020).

Yet while the basic tenets of the resource-availability perspective make good sense and are intuitively appealing, they also rest on the assumption that there is a close correspondence between a person’s objective material circumstances and their subjective physical and social reality. In particular, they suggest that inhabitants of disadvantaged neighborhoods always see their environment as impoverished and uniformly have impoverished experiences within it. However, evidence indicates that disadvantaged neighborhoods are not necessarily viewed by their inhabitants as resource-scarce, just as advantaged neighborhoods are not necessarily viewed as resource-abundant (Macintyre et al., 2008; Pearce et al., 2007). Not least, this is because there is also no guarantee that residents will make use of a neighborhood’s mental health-promoting physical resources (e.g., parks, community spaces; Kaczynski et al., 2014) or its social resources (e.g., through participation in local activities; Campbell & McLean, 2002). Furthermore, it is apparent that residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods does not always lead to negative outcomes for residents (Pearson et al., 2013), particularly where neighborhood cohesion buffers their negative effects (Olamijuwon et al., 2018; Rios et al., 2012).

Moreover, contrary to the assumptions of the resource-availability model, studies suggest that—at least in Western contexts—disadvantaged neighborhoods do not necessarily have fewer available structural and environmental resources than those that are more advantaged (Macintyre et al., 2008; Pearce et al., 2007; Zenk et al., 2017). For instance, Pearce and colleagues (2007) found that community resources in New Zealand (e.g., health care services, recreational facilities, and Indigenous meeting places) were more, rather than less, accessible in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Thus, resource availability could not explain worse health outcomes in those neighborhoods. Furthermore, ethnographic studies show that various forms of social support and resources can be accessed in even the most extreme poverty-stricken neighborhoods (Ager & Parquet, 2008; Desmond, 2012; Payne & Hamdi, 2009). In a similar vein, other research has demonstrated that the local availability of healthy food options does not guarantee healthy dietary behavior (Pearson et al., 2005; Zenk et al., 2017). On this point, there is evidence that the physical proximity of “resources” may not be the best correlate of behavior. For example, one study found that although alcohol outlets in northern California are more likely to be concentrated in poorer neighborhoods, it was residents of more advantaged neighborhoods who consumed more alcohol (Pollack et al., 2005).

These various lines of research speak to two general points that are problematic for the resource-availability perspective. First, the objective material resources that are available in a neighborhood do not necessarily map onto the psychological experience of its residents and hence their mental health. Second, how people make sense of and relate to their environment psychologically can moderate the impact of material resources on mental health outcomes. In what follows, we will explore these issues in greater depth with a view to clarifying how social psychological theory might enrich our understanding of these relationships.

The Exposure Model

Two dominant multilevel models have been applied to understand the effects of neighborhood resource availability on mental health outcomes. The first is the exposure model, which focuses primarily on the negative impact of exposure to environmental features associated with living in disadvantaged neighborhoods. This model identifies a range of potential environmental features that have either positive or negative implications for resident mental health (Julien et al., 2012). Generally speaking, “exposure” to physical and social neighborhood characteristics is considered the key causal mechanism through which mental health is impacted (Miltenburg & van der Meer, 2018). In line with this point, evidence suggests that these effects are dependent upon the dosage of the neighborhood characteristic in question. Dosage can refer to, for example, the time spent living in a particular neighborhood or the level of noise pollution, which differs within and across neighborhoods (as per the unequal exposure hypothesis; Økland & Mamelund, 2019). As this suggests, the dosage is a measure of the intensity of such exposure, and where this is greater and cumulative, then poorer mental health is predicted.

Yet while a dosage-response analysis suggests that there would be a straightforward relationship between physical and social neighborhood exposure factors and mental health, it appears that the relationship is rather more complex (Nuñez-Gonzalez et al., 2020). For example, in one review study, van den Berg and colleagues (2015) found that people who live in neighborhoods with more (vs. fewer) surrounding green spaces tend to report better mental health. In contrast, other review studies found no association between the built environment and mental health nor any long-term benefits of green space for resident mental health (Gascon et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2018). These inconsistencies highlight a key limitation of the exposure model—namely, that it has nothing to say about the individuals whose mental health is helped or harmed by the neighborhoods in which they live. This, however, is an important focus of the contingency model.

The Contingency Model

Contingency models seek to explain differential neighborhood effects observed within the demographic subcategories of people within a given population (e.g., people with limited financial means, children, women, or ethnic minorities; Bolte et al., 2019; Dadvand et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2020). The assumption here is that the effect of a disadvantaged neighborhood on mental health will be more pronounced among socially vulnerable groups (the unequal vulnerability hypothesis; for a review, see Hill & Maimon, 2013). This is theorized to reflect the high dependency on local neighborhood resources within these groups and the fact that they have access to fewer resources outside their neighborhood (Manduca & Sampson, 2019).

In line with this model, there is evidence that the effect of neighborhood disadvantage on mental health interacts with demographic characteristics and that residents may not derive health benefits equally from exposure to the same neighborhood resources (Ludwig et al., 2012; Macintyre & Ellaway, 2003). For instance, findings from the Moving to Opportunity experiment—a housing intervention that allowed low-income households in the United States to move to more affluent neighborhoods—showed mental health benefits for girls but not boys (Gennetian et al., 2012). Similarly, the availability of neighborhood green space has been positively associated with pregnancy outcomes but mainly for members of the (White) majority group rather than women of color (Dadvand et al., 2014). Moreover, other studies suggest that neighborhood disadvantage affects women’s sleeping patterns more than men’s and that the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on depression severity may be more pronounced for older residents (Bassett & Moore, 2014; O’Campo et al., 2015). Along similar lines, residents’ physiological stress responses to living in a disadvantaged neighborhood are stronger for those with low (rather than high) individual-level SES (Ribeiro et al., 2019). Again, as these various lines of evidence suggest, there are differences between subgroups consistent with the predictions of the contingency model. But this provides few insights when it comes to understanding why these differences exist.

Together, then, the resource-availability literature tells us that neighborhood disadvantage exposes residents to mental health risks and that some subcategories of people are more vulnerable to the consequences of a particular exposure. However, it fails to account for the widely observed variation in mental health within subpopulations. The contingency model has little to say about how this happens and why there are different effects of gender and age despite equal exposure to resources. Also, it does not tell us anything about the extent to which residents feel they can draw upon local resources. This knowledge gap can be seen to reflect the fact that much (perhaps most) of the research into the neighborhood-mental health relationship has been conducted by epidemiologists, geographers, and sociologists rather than psychologists (Nuñez-Gonzalez et al., 2020). As a result, most researchers have had more interest in differences that arise as a consequence of demography (e.g., ethnicity and gender) than in those that arise as a function of psychology (notably a person’s identification with a neighborhood and their associated sense of connection to other residents). Yet in so far as the outcomes here are themselves psychological (i.e., concerning mental health), this is a significant shortcoming—albeit an understandable one.

Mediating Pathways Through Neighborhood Perception

Speaking more specifically to questions of psychological process, Galster (2012) highlighted at least 15 different possible pathways between neighborhood factors and health outcomes. Two are particularly important for mental health: social cohesion and perceived environment quality.

Social Cohesion

The social cohesion pathway recognizes the importance of residents’ perceptions of their neighborhood’s social environment for their mental health (Berkman et al., 2015). Specifically, residents who perceive high (vs. low) neighborhood social cohesion, or who live in areas with high levels of social cohesion, tend to have better mental health (Echeverría et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2020). Social cohesion encompasses a diverse array of subconstructs such as network social capital, social support, social participation, solidarity, and collective efficacy (Ehsan et al., 2019; Kawachi & Subramanian, 2018; Pérez et al., 2020). Social cohesion has also been defined as perceived trust, and the ability to activate local networks for cooperation around shared concerns and mutual benefit and is sometimes seen as synonymous with social capital (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2014). Importantly, social cohesion appears to be a critical mediator of the relationship between neighborhood socioeconomic factors and resident mental health at both the individual level (Hong et al., 2014; Kress et al., 2020; Rios et al., 2012) and the neighborhood level (Drukker et al., 2006; Xue et al., 2005).

Yet while the literature broadly supports the idea that neighborhood social cohesion helps to flatten the socioeconomic gradient for health (e.g., as described by Marmot, 2005), the empirical evidence is somewhat mixed. Thus, while a systematic review of reviews indicated that social cohesion was generally associated with better mental health, the strength of this relationship varied across the review studies (Pérez et al., 2020). Similarly, other research suggests that neighborhood-level social cohesion might also be a moderating factor that helps to mitigate the effects of neighborhood disadvantage. Again though, support for this claim is mixed (Echeverría et al., 2008; Fone et al., 2007). In one study, Fone and colleagues (2007) found that the effect of living in a low-income neighborhood on mental health was moderated by neighborhood-level social cohesion. Yet results of a similar study by Echeverría and colleagues (2008) failed to find the same effect.

Bruhn (2009) commented on this inconsistency in a review of the field and highlighted a fundamental problem in construct conceptualization: social cohesion is often a rather loose concept that proves hard to isolate empirically. As he argued, “it has also been frustrating because its multiple definitions prevent its meaningful measurement and application” (p. 31). Relatedly, there is an ongoing debate about its role—specifically, whether an individual’s subjective experience of their social relationships is more protective of health than social cohesion as an externally assessed collective attribute (Mohnen et al., 2015; Poortinga, 2006). Such considerations have led researchers to suggest that social cohesion might function in different ways in different contexts (Bruhn, 2009; Mohnen et al., 2015). For instance, individual-level social relationships in a given neighborhood may provide a person with access to practical support, while group- or neighborhood-level cohesion (i.e., the general sense that residents get along) provides them with a less tangible sense of emotional support (Cruwys et al., 2022b). In line with this view, Mohnen and colleagues (2015) found that individual-level and neighborhood-level indicators of social cohesion were independently associated with better mental health. The former was measured by residents’ self-rated reports of their frequency of contact with friends and family, while the latter was based on aggregated measures of residents’ perceived sociability. Such findings also suggest that a lack of access to social resources at one level might be compensated by access to alternative social resources at another level (Mohnen et al., 2015).

In a similar vein, research suggests that socio-demographic diversity, which tends to be more pronounced in the most economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, can undermine cohesion (Wickes et al., 2014), which may in turn negatively impact mental health. At the same time, though, studies have shown that living in neighborhoods that have a high concentration of members of one’s own ethnic or migrant group can also be protective of residents’ mental health (Dykxhoorn et al., 2020; Pickett & Wilkinson, 2008). Not least, this is because residents of these minority group clustered neighborhoods tend to experience less racial discrimination and increased social support (Denton et al., 2015).

Together, the evidence suggests that the socio-spatial environment of disadvantaged neighborhoods in which minority and migrant families live can still contribute to positive mental health outcomes (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2008). In particular, research highlights the importance of neighborhood social cohesion for mental health and that it is amenable to change in ways that reduce the impact of the neighborhood on health inequality. More specifically, it indicates that living among people with common values, shared social norms, and supportive networks can help to overcome the effects of area disadvantage on health and well-being. So while social cohesion is important, there are outstanding questions about why some residents perceive and experience more cohesion than others who live within the same neighborhood. This means that the role of social cohesion as the mechanism linking neighborhood and mental health is still in need of being properly unpacked and clarified.

Environment Quality

The second pathway between neighborhood and mental health that has received substantial attention centers on perceived environment quality. Here evidence suggests that higher perceived aesthetic quality of the built environment is positively associated with resident mental health (Bond et al., 2012). In contrast, a sense that the physical environment is neglected engenders feelings of mistrust and insecurity and “deeper neighborhood malaise” (Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004, p. 319) that induces psychological and physiological stress responses and undermines resident mental health (Hill et al., 2005). Evidence also suggests disadvantaged neighborhood environments impact poorly on resident mental health indirectly via the perceived quality of their physical features (J. Kim, 2010; O’Brien et al., 2019).

Again, though, perceptions of a neighborhood’s objective features can also vary considerably between residents who share the same space (e.g., Greenberg et al., 1995; Wallace et al., 2015). Moreover, residents who are from disadvantaged neighborhoods and who are of low SES background themselves may not necessarily perceive their neighborhood as “neglected” (Roosa et al., 2009; Thomas, 2016). These discrepancies may in part be due to the difficulty in disentangling the quality of the physical and the social environment (e.g., Dempsey et al., 2010; de Vries et al., 2013). They can also be due to stereotypic beliefs about what good space “looks like” that are taken for granted but actually informed by power, privilege, and positionality (i.e., one’s status as an outsider to a particular environment; Bonam et al., 2017, 2020). More fundamentally, they point to the fact that “there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so”—with the consequence that the objective and subjective dimensions of environmental quality are not always closely aligned.

Related to this point, researchers have also noted that perceptions of neighborhood quality encompass not only features of the material environment but also perceptions of social cohesion, neighborhood trust, and sense of inclusion (Carmona, 2019; Roberts et al., 2020; Wickes et al., 2013). For example, in one field study, residents were asked to describe a high-quality neighborhood. While features of the built environment were mentioned (e.g., schools and traffic conditions), most participants focused on the social characteristics of its residents (e.g., friendliness; as cited in Dempsey, 2010). This suggests that one reason why the contribution of “good-quality” neighborhood environments to mental health varies is that what constitutes “quality” is in large part subjectively determined and encompasses an evaluation of both the social and physical surroundings. Indeed, the physical features of the neighborhood will often be less relevant to perceptions of neighborhood quality than perceptions of the social environment.

Extending this point, research suggests that the physical conditions of neighborhoods are also closely related to neighborhood social cohesion (Sampson, 2012; Wickes et al., 2013). Consistent with this, Sampson (2012) reasoned that cohesive neighborhoods might have access to better physical resources because their residents are more willing to work collectively to improve their local facilities—and may be more effective in doing so. This, in turn, suggests that neighborhood quality may in part be a reflection of collective efficacy, which has been defined as a combination of social cohesion, social control, and shared expectations to intervene in neighborhood issues (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999). Again, though, this does not explain why some neighborhoods are more collectively efficacious than others, nor precisely how this relates to social cohesion in ways that affect (perceptions of) environment quality.

Some clarification of these issues is provided by research which suggests that subjective perceptions of neighborhood cohesion and quality mediate the relationship between features of the objective neighborhood context and resident mental health (J. Kim, 2010; Rios et al., 2012). However, this still assumes that perceived neighborhood cohesion and environment quality are generally lower in deprived neighborhoods, and, as with the resource-availability perspective, this presupposes that there is a lack of (social and physical) resources in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Again, then, this perspective overlooks the potential for mutual trust and collective efficacy to also be features of disadvantaged neighborhoods if residents see themselves as a collective and feel part of their local community (Muldoon et al., 2017). More generally, then, this points to the need for more nuanced theorizing about the social psychological processes that structure residents’ perceptions of their neighborhood’s social and physical environment. Specifically, previous models are not very informative as to how cognitive (perception) and behavioral (efficacy) dimensions interact in the neighborhood context to influence health. It is this clarification that the present review seeks to provide.

Expanding the Resource-Availability Perspective

As we have seen, much of the research that draws on resource-availability models tends to sideline the critical processes of meaning-making that residents engage in to make sense of their neighborhood environment. Greater clarity is needed about the social psychological processes that are involved in generating that meaning. It appears that a key to understanding how structural features of a neighborhood come to benefit mental health lies in knowing whether or not residents see them as resources they can draw upon. In these terms, the effect of neighborhood disadvantage on mental health may be about people’s differential access to neighborhood resources but, more fundamentally, it may be about whether they even see these as resources. This would explain, for instance, why there are inconsistent associations between variables such as the proximity of green space or usage of recreational facilities and mental health outcomes (Kaczynski et al., 2014; Nuñez-Gonzalez et al., 2020). The key, then, is to understand the social psychological processes that determine a person’s capacity and willingness to access the neighborhood resources on which mental health rests.

We propose that this understanding can be provided by broadening the scope of the resource-availability perspective to incorporate the psychological resources that a sense of shared neighborhood identity provides its residents. This involves drawing on theorizing that explains how the objective and structural features of people’s worlds (e.g., neighborhood characteristics) are incorporated into their subjective psychology. One body of work that offers a framework for doing this is provided by social identity theorizing (after Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). This examines (a) how people come to see themselves as members of, and as belonging to, a given neighborhood and (b) how this, in turn, influences their perceptions, affect, and behavior. The social identity approach recognizes that, like all other social groups, neighborhoods are not merely a collection of people and things that are external to the self. Instead, they are social and psychological entities that can also be internalized as a meaningful basis for residents’ self-definition (e.g., as “us Grenfell residents”). Moreover, when one’s neighborhood gets “under the skin” in this way, this has profound implications for mental health (Godkin, 1980). The ways in which these effects are realized are articulated by the social identity approach to health—a social psychological framework that seeks to explain when, how, and why social groups and their associated social identities, enhance and protect (but also sometimes harm) individual health and well-being (S. A. Haslam et al., 2009; C. Haslam et al., 2018; Jetten et al., 2012, 2017).

The Social Identity Approach

There is no doubt that where one lives plays a role in one’s mental health, but it does not do so indiscriminately or consistently. A key question that we posed earlier in this review is why this is the case. Integrating insights from social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and self-categorization theory (Turner et al., 1987), the social identity approach allows us to make sense of this variability by distinguishing between a neighborhood as a physical entity (i.e., as a defined geographical area of co-located residents) and as a psychological entity (i.e., as a group of people who share a sense of themselves as residents of a given neighborhood). In what follows, we argue that the unique value of the social identity approach to neighborhood mental health is that it specifies the social identity processes that shape both group cohesion and perceptions of environment quality. This specification, in turn, explains why exposure to a given neighborhood can be both beneficial and harmful to residents’ mental health.

A major focus of the social identity approach is to explain how members of large groups (e.g., nations) as well as small ones (e.g., families), cohere, trust each other, and develop solidarity—especially in the absence of this being in their members’ personal self-interest (Reicher et al., 2010; Tajfel et al., 1971). Empirical research that has addressed this issue suggests that the critical ingredient here is group members’ social identity—their sense of the self as collective (i.e., “we” and “us”) not just personal (“I” or “me”; Turner, 1982). Precisely because it creates a sense of psychological connection to those others who are part of that collective, social identity is also predicted to have important implications for mental health and well-being (C. Haslam et al., 2018; S. A. Haslam et al., 2009, 2022; Jetten et al., 2012). Not least, this is because feeling disconnected and isolated is itself a significant threat to health (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017).

In line with this proposition, research informed by the social identity approach to health has found that group-based identification prevents the onset of depressive symptoms, protects people from stress and anxiety, and is generally associated with greater resilience (for reviews see Cruwys et al., 2014; C. Haslam et al., 2018). This large body of “social cure” research also shows that group memberships and associated social identities have an important role to play in protecting well-being during periods of transition and life change (e.g., moving home and moving into residential care; Knight et al., 2010; for a review see C. Haslam et al., 2021), and in a range of populations and contexts (e.g., schools and workplaces). Social cure research also indicates that, where they are meaningful and salient, social groups and associated social identities provide community members with access to critical psychological resources—including social support (Bowe et al., 2020, 2022; McNamara et al., 2021; Ntontis et al., 2018; 3 et al., 2021), a sense of meaning, purpose (Kyprianides et al., 2019), and control (Greenaway et al., 2015; Tiessen et al., 2009). Social groups are also a basis for self-esteem (Cooper et al., 2017; Jetten et al., 2015) and trust (Cruwys, Greenaway et al., 2020; Tanis & Postmes, 2005), in ways that generally support mental health and well-being (Flanders, 2016; Kearns et al., 2018).

What Determines the Salience of Neighborhood Identity for Residents?

Just because people live near each other, this does not mean that they will by default self-categorize in group-based terms. On the contrary, self-categorization theory argues that whether or not a given social identity (e.g., as a member of a given neighborhood) becomes salient (i.e., psychologically activated) depends on the dynamic inter-relationship between processes of perceiver readiness and fit (Oakes, 1994). Perceiver readiness is a reflection of the social identities that a person brings to a given context by virtue of the groups they have previously used as a basis for self-definition (e.g., their long-term neighborhood identification). For example, the residents of a given city (e.g., Amsterdam) are more likely to define themselves in terms of their city identity (e.g., as an Amsterdammer) if they have lived there for a long time and previously used this as a basis for self-definition (e.g., when attending sporting events and when interacting with tourists; Hummon, 1992). Fit relates to the match between a particular social identity (i.e., a group-based self-category) and subjectively relevant features of a person’s current social environment. Fit is higher to the extent that a given identity (or self-category) appears to be a sensible way for a person to organize and make sense of the social world and their relationship to it. It has two components. First, comparative fit implies that the extent to which people will define themselves in terms of a particular self-category (e.g., as an Amsterdammer) will depend on who they are comparing themselves to in a given particular context. For example, a resident of Amsterdam (e.g., Roselinde) will be more likely to define herself as an Amsterdammer if she compares herself with tourists rather than only with other Amsterdam residents (S. A. Haslam et al., 1995). Second, normative fit relates to the content of this match and will tend to be greater where the nature of observed differences is consistent with a perceiver’s expectations about the identity in question. For example, Roselinde will be more likely to define herself as an Amsterdammer when she sees city residents, but not tourists, doing “Amsterdammer things” (e.g., making poffertjes) rather than the other way around (Oakes et al., 1991).

Importantly, these processes of identification and identity salience are also affected by neighborhood features. For example, other things being equal, a given neighborhood identity is more likely to become salient for a resident when the neighborhood is well-established and that person has lived there for a long time so that they (and others) have a history of acting in terms of this identity (what Relph, 1976, refers to as existential insideness and Tuan, 1980, as rootedness; see Hummon, 1992). This perceiver readiness will also be increased if there are activities (e.g., community festivals, political activism) and structures (e.g., newsletters, signage, facilities) that reinforce the identity—and make it “feel like” a neighborhood—in an ongoing way (Haeberle, 1987, p. 194; Smith, 1984). At the same time, the comparative fit of a given neighborhood identity will be increased if the neighborhood has well-defined geographical boundaries and characteristics (e.g., rivers, roads, and other geographical features) that distinguish it from other neighborhoods and that are understood to do so in community narratives (Chaskin, 1997; Newman & Paasi, 1998; Reicher et al., 2006). And alongside this, normative fit will be increased if the features of a neighborhood are perceived to map onto residents’ needs and expectations (e.g., for specific infrastructure such as schools and shops). Importantly, these latter features may be related to the sorts of features identified as important by resource-availability models, but there is no necessary link here. For example, whether access to green space increases the salience of a person’s neighborhood identity will depend on whether this is normatively relevant to that identity (Morton et al., 2017).

In this way, features of the prevailing social context interact with a person’s prior experience to determine which social identity they use to define themselves—and indeed whether they define themselves in terms of social identity at all. Importantly too, when a particular social identity becomes salient for a given individual, this then becomes a basis for their perception and behavior. For example, if Roselinde self-defines as an Ajax FC supporter, then she is more likely to want to go and see Ajax play, and more likely to get excited when they score a goal (S. A. Haslam et al., 2020). In this context too, her sense of self should extend to embrace other supporters of Ajax—so that she feels a great sense of connection to them, is more trusting of them, more open to their influence, and more likely to act in concert and solidarity with them (S. A. Haslam, 2004).

Two key hypotheses can be derived from this analysis that relate specifically to matters of group membership and health (C. Haslam et al., 2018). First, the social identity hypothesis suggests that when people see themselves as sharing a common social identity, this makes group behavior possible (Turner, 1982). In a given neighborhood, then, this means that residents will be more likely to come together to cooperate and work as a group to the extent that they have internalized a shared neighborhood-based social identity as members of a common community (what we henceforth refer to as neighborhood identity). Reflecting people’s capacity to define themselves as members of a common territorial group, this neighborhood identity also encapsulates attributes and qualities that residents perceive themselves as sharing with other ingroup members (e.g., as people who are middle-class, who value green space, who look out for each other, who are family-oriented). In this way, a neighborhood identity provides residents with a place-based social identity that says something about “who we are” and “where we belong”—in ways that align with points made in a large literature about the importance of place-identity (Proshansky et al., 1983) and place-based belonging (see Altman & Lowe, 1992; Antonsich, 2010; Dixon & Durrheim, 2000, 2004; Hummon, 1992). This identity is also a basis for social cohesion and collective action designed to advance the interests of that ingroup. For example, if a neighborhood area is perceived to be threatened by rising crime, increasing traffic, or unscrupulous development, then residents are more likely to come together to try to counteract that threat if they share a strong sense of neighborhood identity. At the same time, the threat itself could also increase that sense of neighborhood identity because it increases the fit of this social self-category for those same residents (Branscombe et al., 1999; Doosje & Ellemers, 1997).

Second, and related to this, the identification hypothesis suggests that people will experience the social and health benefits (or costs) of a given group membership only to the extent they identify with that group (C. Haslam et al., 2018). In the case of neighborhood identity this means that while some members of a given community will internalize this into their sense of self (and hence be ready to act in terms of it), others will not. As a result, the former residents will be able to draw on that identity as a social and health-enhancing resource but the latter will not (Jetten et al., 2014). This is something that bell hooks (2009) captures in her reflections on the nature of belonging arising from her experiences as an isolated woman of color growing up in Kentucky:

While my early sense of identity was shaped by the anarchic life of the hills, I did not identify with being Kentuckian. Racial separatism, white exploitation and oppression of black folks, was so widespread it pained my already hurting heart. . . Growing up in that world of Kentucky culture where the racist aspect of the confederate past was glorified, a world that for the most part attempted to obscure and erase the history of black Kentuckians, I could not find a place for myself in this heritage.

In line with this proposition, research indicates that the strength of people’s social identification with others in their local and national community increases their sense of personal control and wellbeing (Greenaway et al., 2015). Critically too, shared identity as members of a given community (e.g., a region or nation) is a platform for trust, support and cohesiveness among group members in ways that enable them to work together effectively (Bonetto et al., 2022; Reicher & Haslam, 2010). But, as hooks indicates, without those things, the picture is a lot bleaker.

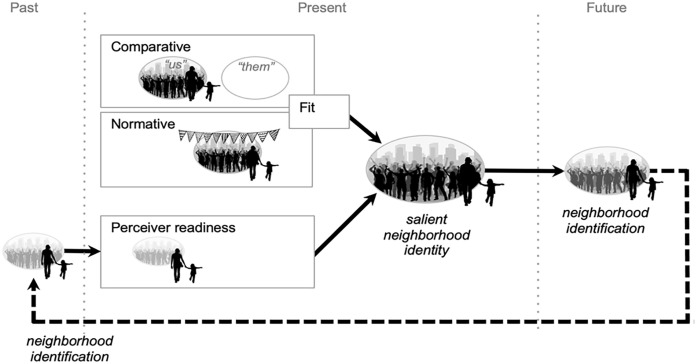

As this reasoning suggests, the health benefits (and, at times, pitfalls) of neighborhood identification are driven by the social context in which a person lives, in interaction with their prior experience of that context. More specifically, as Figure 1 suggests, the salience of a given neighborhood identity reflects its normative and comparative fit in the situation at hand together with a person’s readiness to enact that identity (Oakes, 1994). For example, Nadia is more likely to identify with her neighborhood in Sydney if she has lived there for a long time (so that she has more experience in defining herself as a member of the neighborhood) if she is attending an enjoyable neighborhood event (e.g., a festival, so that the identity is normatively fitting), and if the neighborhood is clearly different from others (“them”—e.g., developers looking to build a new high-rise development or a council proposing to close a community center). In this case, then, if Nadia identifies highly with others in her neighborhood she is more likely to feel she can cope with future changes, which will be protective for her wellbeing. Similarly, if others share this same neighborhood identity, and perceive these developments as a threat to that identity, they might be motivated to band together to oppose them (Drury & Reicher, 2000).

Figure 1.

The Process Through Which Neighborhood Identity Becomes Salient (in Ways That Build Neighborhood Identification) as Specified by Self-Categorization Theory (Oakes, 1994, and Adapted From C. Haslam et al., 2018).

Note. At a given point in time, a particular neighborhood identity (as “us members of this community”) becomes salient—and hence is a basis for perception and action—to the extent that it is comparatively and normatively fitting (so that the identity makes sense for the self in context) and has been enacted in the past and therefore is a social cognitive resource that is ready to be activated. Speaking to the ongoing dynamic interrelationship between identity salience and identification, the process of enacting the identity also feeds into a state of neighborhood identification that contributes to perceiver readiness which increases the likelihood of the neighborhood identity becoming salient again in the future (for evidence of these processes at play in relation to other identities, see Blanz, 1999; S. A. Haslam, 2004).

Neighborhood Identity and Mental Health: Three Key Hypotheses

The above arguments explain how neighborhood identity might serve to protect residents’ mental health. Nevertheless, it is useful to spell these out in more detail and to organize them around three key hypotheses. The first of these is as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): When residents relate to each other in terms of a shared neighborhood identity, this will tend to be protective of their mental health.

An important feature of shared social identity is that it transforms people who might otherwise be strangers into fellow ingroup members (Neville & Reicher, 2011; Turner et al., 1987). In this way, shared identity is the basis for meaningful connection that, among other things, imbues group members with a sense of common purpose and a belief that support is available, if and when they need it. This, in turn, will tend to be beneficial for mental health (Bowe et al., 2020; Kyprianides et al., 2019).

Social identity theorizing also provides a framework for understanding why neighborhoods with a high concentration of members of the same minority ethnic group might experience good mental health. This is because the high (comparative and normative) fit of ethnic group self-categorization should mean that such neighborhoods are more likely to furnish residents with a strong sense of shared identity (vs. neighborhoods that have a low density of an ethnic ingroup; Postmes & Branscombe, 2002) and as a result they should provide residents with greater access to key psychological resources (i.e., a sense of support, meaning, purpose and control; C. Haslam et al., 2018). In the process, all else being equal, those communities are also in a better position to protect and enhance their sense of shared identity (i.e., “our way of life”) and to insulate residents from harmful forces in wider society (especially stigma and discrimination; Frisch et al., 2014; McIntyre et al., 2016, 2018).

At the same time, though, this claim needs to be understood in the context of the broader intergroup dynamics that give rise to such concentration. In particular, the beneficial effects of living in neighborhoods with a concentration of members of the same minority group will be conditioned by the reasons for that concentration—and, in particular, will be attenuated if they are the product of efforts on the part of others (e.g., a majority ethnic group) to marginalize or oppress a specific minority group (Berg, 1975; Newman et al., 2013). Nevertheless, even under these circumstances, shared social identity will still have some health-protective impact. This relates to a second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): A sense of shared neighborhood identity will tend to buffer residents’ mental health from the negative effects of exposure to (a) neighborhood disadvantage and (b) neighborhood change.

As we have seen, socioeconomic deprivation is associated with poor health outcomes. However, a shared social identity functions as a buffer against environmental stressors because it provides access to a raft of health-protective psychological resources (C. Haslam et al., 2018; S. A. Haslam & Reicher, 2006) that also serve to attenuate physiological stress-responses (Hausser et al., 2012). As a result, in the face of structural (Bakouri & Staerklé, 2015) and physical challenges (Ekblad et al., 1992; Novelli et al., 2013), residents who define themselves as part of a shared neighborhood group are likely to be more resilient. In this way, neighborhood identity shapes perceptions of the socio-structural environment and plays a crucial role in determining whether the putative benefits of group membership (e.g., access to support and beneficial environmental resources) are unlocked. Among other things, this means that neighborhood identity can allow people to develop and access powerful forms of cultural capital (Yosso, 2005) and transform the adverse effects of belonging to a disadvantaged community into a health-promoting force. Similarly, when residents internalize a shared neighborhood identity, they are more likely to appraise neighborhood conditions and change more positively. They will also be in a better position to manage any anxiety that is associated with the change—notably by providing each other with cognitive, emotional, and practical support (S. A. Haslam et al., 2005; S. A. Haslam & Reicher, 2006; Stevenson et al., 2019, Stevenson, Costa, Easterbrook, et al., 2020). A third and final hypothesis follows on from this:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): When residents share a sense of common neighborhood identity, this will tend to increase the likelihood that they see their neighborhood as cohesive and therefore increase their willingness to work together in ways that support mental health.

Where residents share a sense of social identity, a basic prediction of self-categorization theory is that this is likely to lead them to see themselves as being more similar, as having more in common, and as being more entitative (i.e., as a more coherent and cohesive entity, “us”; Turner et al., 1987; see also S. A. Haslam et al., 2022). This sense of “us-ness” in turn provides a psychological platform for residents to work collectively to overcome any challenges that they face—for example, by sharing resources, forming a neighborhood watch group, petitioning the council to reduce traffic congestion or environmental degradation, or fighting back against an unjust local authority (Brown et al., 2003; Drury & Reicher, 2000; Kingsley et al., 2019; Ohmer et al., 2006; Tekin & Drury, 2023). And again, this sense of cohesion and collective efficacy that is underpinned and motivated by shared social identification should have positive consequences for mental health.

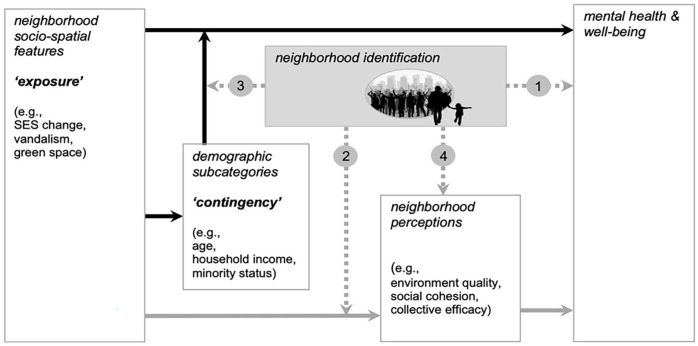

A Social Identity Model of Neighborhood Mental Health

To get a clearer sense of how the social identity approach extends on the resource-availability perspective, the foregoing arguments can be integrated within a model that conceptualizes neighborhood identification as the missing link between the features of a given neighborhood and the mental health of its residents. More specifically, as Figure 2 indicates, a key feature of this model is that neighborhood identification functions in three distinct ways. First, as predicted by H1, it has a direct link to mental health (Pathway 1); second, as predicted by H2, it has two interactive pathways that moderate the effects of variables specified in resource-based exposure and continency models (Pathways 2 and 3). Finally, as predicted by H3, it has a link to mental health via neighborhood perceptions (Pathway 4). We round out this review by clarifying the nature of these four pathways as well as the evidence that supports them.

Figure 2.

A Social Identity Model of Neighborhood Mental Health.

Note. This model presents neighborhood identification as the missing link in current models of the relationship between neighborhood and mental health. In particular, this is implicated in four key pathways between neighborhood features and mental health.

Pathway 1 suggests that neighborhood identification will have a direct impact on mental health and that this operates in addition to (and is separable from) exposure to neighborhood features and their interaction with an individual’s demographic variables. More specifically, where neighborhood identification is strong, this should tend to have corresponding beneficial consequences for mental health.

Evidence to support this claim comes from research by McIntyre and colleagues (2018) which drew on population data from residents of northwest England. This found that neighborhood identification was negatively associated with residents’ paranoia and depressive symptoms when controlling for gender, ethnicity, education, and employment status. Further support comes from two studies using a large nationally representative sample from the Household, Income Labor Dynamics in Australia (the HILDA survey; Fong et al., 2019a) and an online experiment that manipulated neighborhood identification (Fong et al., 2019a). Results of both studies provide evidence for Pathway 1 as do two more recent studies of residents in over 900 neighborhoods in Australia (one of them experimental; Cruwys et al., 2022a). A third study, also using HILDA data from two timepoints, found that positive change in neighborhood identification between 2011 and 2016 was protective against mental ill-health at Time 2 (Fong et al., 2019b). Again, all these studies observed a positive association between residents’ neighborhood identification (or increased neighborhood identification) and mental health when controlling for a range of relevant demographic variables.

Pathways 2 and 3 suggest that neighborhood identification also functions as a moderating mechanism that can help to explain when objective neighborhood factors will affect mental health. First, neighborhood identification has an impact on established mediating pathways including perceptions of environment quality and social cohesion (Galster, 2012). Second, it has a bearing on the interaction between neighborhood exposure and contingency. These pathways speak to the fact that when residents identify highly with their neighborhood, this will generally lead them to perceive the objective features of their residential environment in more positive terms (i.e., as being of better quality and more cohesive) than do low identifiers (Brown et al., 2003). In this way, strength of identification can buffer residents from environmental features associated with neighborhood disadvantage (e.g., poor environment quality), and neighborhood change (e.g., to socioeconomic profile) in ways that again will tend to be beneficial for their mental health and wellbeing.

Many studies provide support for these interactive pathways. Particularly persuasive is a program of experimental and observational studies of temporary residential communities that have shown how social identification shapes the environmental perceptions of pilgrim communities attending the Prayag Magh Mela religious festival in northern India (Hopkins & Reicher, 2016; Pandey et al., 2014; Shankar et al., 2013; Srinivasan et al., 2013). During this festival, millions of people from all over India come to live together in rudimentary campsites of makeshift tents, and in the course of doing so, are exposed to a harsh physical environment. Held in winter, the pilgrimage can last for an entire month, during which the most devout pilgrims forego modern conveniences and endure extreme environmental hardships (e.g., cramped, noisy, freezing, and unsanitary conditions) as part of their spiritual journey (Hopkins & Reicher, 2016). Findings from these studies highlight how group identification transforms people’s perceptions of objective environmental features. For public health officials, crowded environments are typically seen as health hazards and as major threats to mental health (Regoeczi, 2008). However, evidence suggests that pilgrims have a qualitatively very different experience to this because their psychological group membership restructures the experience of these environments into one that is restorative and, indeed, beneficial for mental health (Hopkins & Reicher, 2016). Consistent with this claim, Pandey and colleagues (2014) found that social identification, even with a temporary residential community, provided pilgrims with the means to cope with the duress of the winter cold. In this way, pilgrims’ sense that they shared identity with, and hence were supported by fellow worshippers at the campsite, was associated with them perceiving the near-freezing temperatures as less severe and less painful.

Social identification was also found to influence pilgrim’s appraisal of noise at the festival. Objectively, the average noise level throughout the Magh Mela was well over the recommended safety levels (i.e., > 70dB). Indeed, outsiders (i.e., outgroup members) who were exposed to this sustained noise reported finding it intensely annoying and concurred with health officials that long-term exposure to it would be damaging. In stark contrast, however, pilgrims who shared a sense of common group identity appraised the noise as pleasant and joyful (Shankar et al., 2013). Moreover, Shankar and colleagues (2013) confirmed that it was the identity-defining nature of the noise that shaped perceptions—such that noise that contributed to participants’ religious experience (e.g., prayers, chanting) was perceived positively, whereas equally loud noise that was considered to be irrelevant to their religious experience (e.g., public service announcements and political broadcasts) was perceived negatively.

Findings from this collection of studies have subsequently been replicated in other contexts (Morton et al., 2017; Ysseldyk et al., 2016) and other experimental studies of crowded environments (Alnabulsi & Drury, 2014; Drury et al., 2015). The conclusions here also accord with literature on community place attachment which has found that people who feel a sense of connection to their neighborhood perceive there to be less incivility within it, have a lower fear of crime, and a greater sense of neighborhood cohesion, control and collective efficacy (Brown et al., 2003; Manzo & Perkins, 2006; Scannell & Gifford, 2010). In this vein, Rivlin’s (1982) ethnographic research with members of a Hasidic sect in New York points to ways in which shared group membership furnishes residents with deep connections to places that can be unfathomable to outsiders. Hence what others find depressing, residents themselves may find reassuring. As she concludes:

The identity of the area . . . is shared by the members as they live or visit in the area, contributing to the way they view themselves. Essential in this process is the prior identification with the group, for it is this identification that gives both the personal contacts and the geography their special meanings. (Rivlin, 1982, p. 89)

Experimental research supports similar conclusions. In particular, a series of three experiments by Morton et al. (2017) shows that the restorative benefits of exposure to nature are conditional on whether the type of nature in question is relevant to a perceiver’s salient social identity. Thus, when residents of a city in the United Kingdom (Exeter) were led to define their identity as rural, their cognitive functioning was enhanced by exposure to rural stimuli (e.g., fields and trees). However, when they were led to define that same identity as urban, their cognitive functioning was improved by exposure to urban stimuli (e.g., buildings and streets). Together, such research reinforces the key message that salient social identities provide a lens through which objective features of the environment are appraised and transformed—in ways that can be both positive and profound (at least from the perspective of those who embrace those identities). This observation raises an important question: Are objectively harmful features of an environment that are perceived positively by high-identifiers (in ways that are good for their mental health), still damaging to physical health? There is certainly potential for this to be the case, and indeed a large body of research (e.g., in the areas of addiction and risk perception) speaks to the fact that the capacity for “social cure” can be bound up with potential for “social curse”—especially where ingroup activity and norms are threatening to physical health (e.g., Cruwys et al., 2020, 2021; Hopkins & Reicher, 2021; Howell et al., 2014; Morton & Power, 2022; Oyserman et al., 2007; Payne & Hamdi, 2009).

There is also evidence that provides more focused support for each of these two pathways. Support for Pathway 2 again comes from the HILDA survey—with Fong and colleagues (2019a, Study 1) observing that neighborhood identification moderates the impact of neighborhood socioeconomic conditions on perceived environment quality. More specifically, this research found (a) that high neighborhood identifiers—including those residing in low SES neighborhoods—tended to perceive their neighborhood to be of higher quality than low identifiers and (b) that this, in turn, predicted better mental health, even when controlling for age, gender, marital status, and educational attainment. This pattern of results was then replicated in an experiment that randomly assigned participants to one of four conditions (high vs. low neighborhood identity × high versus low neighborhood SES; Fong et al., 2019a, Study 2). These findings thus provide evidence of the causal impact that neighborhood identification and SES can have on perceptions of environment quality, and in turn, on the latter’s association with mental health. Importantly, these results also replicated the previously observed interaction, such that the negative effect of low neighborhood SES on perceptions of environment quality was attenuated only among participants in the high (vs. low) neighborhood identification condition (Fong et al., 2019a).

Pathway 3 suggests that neighborhood identification can also explain variability in support for contingency models of neighborhood exposure. That is, it suggests that differences in neighborhood identification can explain why some groups of residents (in particular, low neighborhood identifiers) are more susceptible to neighborhood exposure and contingency effects than others. Evidence for this pathway again comes from a study that analyzed data from the HILDA survey (Fong et al., 2019b). Using a pre-post two timepoint design and linkage with Australian Census data, this examined a representative sample of neighborhoods over 5 years coinciding with unprecedented rapid neighborhood-level socioeconomic change. The study found that increased neighborhood identification over this period interacted with a change in both neighborhood SES (an exposure variable) and personal financial status (a contingency variable) to predict reduced risk of mental ill-health. And once more, this pattern in the findings held when controlling for residents’ age, sex, marital and homeownership status.

As Pathway 4 suggests, neighborhood identification is also critical to the process of building and maintaining neighborhood cohesion and connectedness in ways that ultimately prove beneficial for mental health. Moreover, high identifiers are more likely to trust their neighbors, and hence be open to (rather than ignore) their support, in ways that benefit their mental health. Evidence that partially supports this claim comes from a longitudinal three-time point study that recruited residents from all over Australia to reach out to neighbors as part of a national “Neighbor Day” campaign designed to raise awareness of the importance of connecting with other residents in one’s community (Fong et al., 2021; see also Cruwys et al., 2022b). This study found that the act of hosting a neighborhood gathering or reaching out to neighbors in meaningful ways boosted residents’ sense of neighborhood identification over a 6-month period. Critically too, this led to enhanced social cohesion and reduced loneliness two months later, and to improved well-being 6 months later (thereby providing additional support for Pathway 1). At the same time, there was no direct link between social cohesion and well-being, suggesting that it is neighborhood identification that is the more specific active ingredient here. Also supporting our social identity model, this study showed that efforts to boost mental health by building neighborhood identification are scalable and can have both broad relevance (e.g., to small gatherings as well as large public events) and widespread reach (e.g., potentially benefiting hundreds of thousands of people).

Neighborhood community identification has also been shown to influence perceptions of the social environment in ways that benefit psychological well-being in several cross-sectional studies (Heath et al., 2017; McIntyre et al., 2016; McNamara et al., 2013; Stevenson et al., 2019, 2020). In particular, Heath and colleagues (2017) surveyed residents from five neighborhoods in southwest England, in the context of urban regeneration, and found that community identification provided a platform for both perceived social support and collective esteem. In turn, support and collective esteem predicted residents’ well-being, resilience, and willingness to pay back to the community. Similarly, across four highly disadvantaged neighborhoods in Ireland, McNamara and colleagues (2013) found that community identification positively predicted residents’ sense that their neighbors were a source of social support. They also found that the link between identification and well-being was through residents’ sense of collective efficacy in the neighborhood. Links between neighborhood identification and well-being have also been reported in studies by Stevenson and colleagues (2019, 2020) that examine socially diverse neighborhoods in England and Northern Ireland. These researchers found that neighborhood identification was associated with well-being via reduced intergroup anxiety (2019) and perceived neighborhood support (2020). Payne and Hamdi (2009) also provide some powerful qualitative evidence that aligns with this analysis in their study of the “street love” that U.S.-born African men show to each other in their local community. In particular, they note that a sense of shared identity borne out of adversity is a basis for mutual support and resilience.

Together, then, these various studies reinforce claims that residents’ strength of social identification with their neighborhood is a critical determinant of their mental health and responses to the material conditions of that community. Thus, while the walls, fences, and property boundaries in a neighborhood may create a sense of physical separation, this can be counteracted by a sense of shared neighborhood identity. Likewise, while the deprivation of a particular neighborhood will generally be harmful to health (e.g., Ribeiro et al., 2019), in-group identification can also buffer against this by increasing residents’ access to support, solidarity, and eustressing (rather than distressing) experiences (S. A. Haslam & Reicher, 2006; Payne & Hamdi, 2009; Rivlin, 1987).

Constraints on Generality and Directions for Future Research

Although there is substantial support for the social identity model of neighborhood mental health and the four pathways that it contains, our confidence in it is nevertheless limited by the nature of the evidence that has been drawn upon to develop it. In particular, there are three interrelated caveats that need to temper our enthusiasm for the model.

The first of these is that while the social identity model is multifaceted and complex (as is clear from Figure 2), this is generally less true of the research that has informed its development. In particular, most research pertains to just a single pathway in the model, and, to date, no study has simultaneously explored more than two pathways at the same time. Accordingly, there are questions about how the pathways relate to each other and how they play out simultaneously in the world. For example, is the direct path from neighborhood identification to mental health (Pathway 1) ultimately less important than the indirect pathways via social cohesion (Pathway 2) and subgroup membership (Pathway 3)? Questions of this form can ultimately only be answered by further research (e.g., of the form reported by Fong et al., 2021) which investigates these pathways simultaneously and, in the process, furnishes us with a more integrated understanding of the manifold importance of neighborhood identification for mental health.

A second issue is that while we consider the social identity model to provide a general framework for understanding neighborhood mental health; thus far, the evidence that has been used to develop this model has generally been obtained in Westernized contexts where extreme poverty is relatively rare. As Baffoe and Kintrea (2022) note in a recent review “the present situation largely reflects a world of rich-country academics studying ‘first world’ built environment and social problems, and diseases of the relatively privileged” (p. 12). As noted at the start of this review, this is the world of which we ourselves are members. Nevertheless, some of the research that we have discussed has been conducted in countries that are not affluent (notably India; Hopkins & Reicher, 2016; Pandey et al., 2014; Shankar et al., 2013) and with disadvantaged subpopulations (e.g., Heath et al., 2017; McNamara et al., 2013; Tekin & Drury, 2023). For all that, though, there is clearly a need to test the model in a broader set of non-WEIRD contexts to establish its generalizability (Henrich et al., 2010). That said, we are reasonably confident that the core elements of the model—particularly, those built around “social cure” theorizing—are broadly applicable insofar as the key tenets of this theorizing have been tested and supported across a very broad range of cultures and conditions and by researchers who bring a range of different identities to the research table (e.g., Chang et al., 2016, 2017; Lam et al., 2018; Muldoon et al., 2017; van Dick et al., 2021).