Abstract

Vaginitis, a prevalent gynecological condition in women, is mainly caused by an imbalance in the vaginal micro-ecology. The two most common types of vaginitis are vaginal bacteriosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis, triggered by the virulent Gardnerella vaginalis and Candida albicans, respectively. In this study, a strain capable of inhibiting G. vaginalis and C. albicans was screened from vaginal secretions and identified as Lactobacillus gasseri based on 16S rRNA sequences. The strain, named L. gasseri VHProbi E09, could inhibit the growth of G. vaginalis and C. albicans under co-culture conditions by 99.07% ± 0.26% and 99.95% ± 0.01%, respectively. In addition, it could significantly inhibit the adhesion of these pathogens to vaginal epithelial cells. The strain further showed the ability to inhibit the enteropathogenic bacteria Escherichia coli and Salmonella enteritidis, to tolerate artificial gastric and intestinal fluids and to adhere to intestinal Caco-2 cells. These results suggest that L. gasseri VHProbi E09 holds promise for clinical trials and animal studies whether administered orally or directly into the vagina. Whole-genome analysis also revealed a genome consisting of 1752 genes for L. gasseri VHProbi E09, with subsequent analyses identifying seven genes related to adhesion and three genes related to bacteriocins. These adhesion- and bacteriocin-related genes provide a theoretical basis for understanding the mechanism of bacterial inhibition of the strain. The research conducted in this study suggests that L. gasseri VHProbi E09 may be considered as a potential probiotic, and further research can delve deeper into its efficacy as an agent which can restore a healthy vaginal ecosystem.

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Microbiology

Introduction

The female vagina is a dynamic microecological environment, where balance is largely maintained by the vaginal microflora which is dominated by Lactobacillus species1. Indeed, in women of childbearing age, the presence of this particular genus has long been recognized as essential for a healthy vaginal environment1. So far, approximately 25 different types of lactobacilli have been reported as forming a complex population in the vagina, and these include Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus gasseri, Lactobacillus iners and Lactobacillus jensenii as the predominant species2–6. Given their importance, any imbalance in the vaginal microbiota that reduce Lactobacillus levels can subsequently allow the emergence of other dominant endogenous or exogenous bacteria. This can result in a number of gynecological disorders that get translated into physical and mental discomfort which eventually affect a woman’s daily life. Some of the outcomes of such an imbalance in the vaginal microecological environment include vaginal bacteriosis, cytolytic vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, trichomonas vaginitis, urinary tract infection and other infectious diseases of the female genitourinary tract7–9.

Bacterial vaginitis (BV) is characterized by elevated vaginal pH, malodorous discharge, and it is considered to be a polymicrobial condition in which pathogenic bacteria, predominantly Gardnerella vaginalis, form a biofilm on the vaginal wall10–13. Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), was reported to be the second most common form of vaginitis, with 75% of female patients being women of childbearing age14,15. In this case, 90% of VVC infection is primarily due to the attachment of Candida albicans to vaginal cells to form a biofilm15–17.

Currently, the main clinical strategy for treating BV involves the use of antibiotics such as metronidazole, clindamycin and tinidazole18, with short-term cure rates close to 80%19. VVC is primarily treated with antifungal drugs, such as azols and ibrexafungerp20. It has also been reported in the literature that topical boric acid and flucytosine can also be therapeutic21. However, vaginitis often recurs after drug treatment, and this highlights the need to identify safe and effective alternative treatments to alleviate the physical and psychological burden on patients.

Lactobacillus can maintain the ecological balance of the genitourinary tract through various mechanisms such as host immune regulation, recovery of the vaginal microbiota and interference with pathogen colonization22,23. In addition, lactobacilli can also inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria through the production of bacteriostatic substances such as hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins, while being able to competitively repel such pathogens through the production of adhesins24–26. Clinical studies have shown that orally or vaginally administered microecological agents can significantly reduce morbidity and recurrence of vaginitis27–29. For instance, Shamshu et al.30 noted the therapeutic effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14 on reproductive tract infections, while Reznichenko et al.31 reported reduced BV recurrence and prolonged duration of recurrence with Lactobacillus crispatus LMG S-29995, Lactobacillus brevis Lbr-35 and Lactobacillus acidophilus La-14. Similarly, Rosario Russo et al.32 showed that a combination of Lactobacillus acidophilus GLA-14 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 with lactoferrin reduced the symptoms and recurrence of VVC.

The objectives of this study were to isolate Lactobacillus strains from vaginal secretions before identifying the isolates and assessing their safety. The in vitro probiotic effects of the isolates against Gardnerella vaginalis and Candida albicans were then determined. It is expected that the results of this study will assist the introduction of new probiotics with therapeutic potential for promoting women’s health.

Materials and methods

Isolation and identification of LAB strains

According to the 2019 “Implementation Rules of Administrative Regulations on Human Genetic Resources”, samples were obtained in accordance with the biobank’s standard operating practices after securing informed consent from the sample provider33. The general procedure is to sign an informed consent form with the volunteers who participate in the sampling, then provide the volunteers with the sampling tools and sampling procedure, and the volunteers take the samples by themselves and deliver the samples to the laboratory. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were then isolated from these samples using MRS medium. Both Gardnerella vaginalis and Candida albicans were commercially purchased strains (BeNa, China).

Taxonomic classification of the isolates was achieved through 16S rRNA sequence analysis by following methods reported in literature34. New isolates were also identified by database sequence comparison. In addition, sequences of closely related strains were retrieved from the GenBank Library Project database to construct a phylogenetic tree, based on the Neighbor-Joining method, using MEGA 11.0 software.

Antimicrobial activity

The Oxford Cup method was used to evaluate the inhibitory activity of the isolated strains against G. vaginalis35,36. For this purpose, 50 µL of G. vaginalis, at a concentration of about 109 CFU/mL, was evenly spread on Columbia Blood Agar plates using a sterile applicator stick before adding 100 µL of bacterial test strain solution (109 CFU/mL) to determine its bacteriostatic ability. The inhibitory effects of the isolates against C. albicans were then tested using the method of Zhang et al.37. 5 µL of the isolate broth (109 CFU/mL) was dripped onto the prepared MRS agar plate, then dried and cultured for 48 h to allow the colony to grow. Then 5 mL of semi-solid Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) medium containing Candida albicans (106 CFU/mL) was poured onto the plate containing the colony, dried and cultured for 24–48 h. In both cases, the diameter of inhibition zones, indicative of the inhibitory activity of the isolates, was evaluated.

The enteropathogenic bacteria Escherichia coli and Salmonella enteritidis also served as indicator strains for testing the bacteriostatic capacity of the isolates using the Oxford cup method. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Hydrogen peroxide production

H202 production by LAB was determined using the method of McGroarty et al.38. Briefly, isolates on MRS plates containing 10 g/L glucose, 0.25 g/L tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, Macklin, China) and 0.01 g/L horseradish peroxidase (Macklin, China), were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 48–72 h. They were then exposed to ambient air, and since in the presence of H2O2, horseradish peroxidase in the medium oxidizes TMB to form blue pigments, a color change was indicative to H2O2,-producing colonies.

Co-culture of LAB strains and pathogens

For this experiment, G. vaginalis was cultured in BHI broth medium supplemented with 5% bovine serum, while LAB and C. albicans were cultured in MRS Broth and Sabouraud Dextrose Broth, respectively.

Co-culture experiments with LAB strains and pathogens were performed according to the method of Bo Ram Beck er al. to determine bacteriostatic effects39. To test activity against G. vaginalis, the pathogen and LAB (both at 109 CFU/mL) were inoculated at 1% (v/v) inoculum into BHI broth containing 5% bovine serum prior to aerobic incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. Similarly, to determine activity against C. albicans, MRS broth (10 mL) was inoculated with 1.0% (v/v) of LAB (109 CFU/mL) and 1.0% (v/v) of C. albicans (107 CFU/mL). This was followed by a 24 h aerobic incubation at 37 °C. Media inoculated with G. vaginalis or C. albicans alone were used as the control. The viable bacteria count (CFU/mL) of each pathogen in the experimental and control groups were then measured. The selective media used were Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) medium for C. albicans and Columbia Blood Agar (CBA) medium for G. vaginalis. The inhibition rate (%) was eventually calculated as follows:

Adhesion test on Caco-2 and vaginal epithelial cells

Caco-2 and vaginal epithelial cells were purchased from Shanghai Goyan Bio. Co. (Shanghai, China). The adhesion experiment was then carried out according to previous research, with some modifications40.

Vaginal epithelial cells were cultured in specialized medium (Goyan Bio., Shanghai), while Caco-2 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin solution. The adhesion test was then performed in a 24-well plate, and briefly, this involved adding 2.5 × 105 cells to each well prior to a 24-h incubation at 37 °C to allow cell attachment. The number of cells was calculated using a blood cell counting board. The medium was subsequently discarded and after washing the wells twice with phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.0) to remove unattached cells, 1 mL (107 CFU/mL) of bacterial suspension was added to the wells. This was followed by a 2-h incubation at 37 °C and under 5% CO2 to allow bacterial adhesion to the cells. Unstuck bacteria were then removed by adding 300 uL of pancreatin to detach the cells from the wall before adding 700 uL of culture solution to stop digestion. The number of viable bacteria was finally measured by plate counting method, with the adhesion index calculated using the following formula:

Inhibition of pathogen adhesion to vaginal epithelium

The vaginal epithelial cell adhesion assay was used to evaluate the inhibitory effects of LAB against G. vaginalis and C. albicans25,37. In this assay, the concentrations of both LAB and pathogenic bacteria were adjusted to 1.0 × 107 CFU/mL, with 2.5 × 105 cells subsequently added to each well of a 24-well plate. A mixture of LAB and pathogen suspensions (500 μL), prepared from equal volumes of each, was then added to the plate. In this experiment, vaginal epithelial cells incubated with G. vaginalis or C. albicans alone acted as the controls. All tests were conducted in triplicate, and the number of pathogenic bacteria in the experimental and control groups was determined separately. The pathogen adhesion indexes of the control group were finally compared with those of the experimental group, with the difference reflecting the test strain’s inhibitory effects on pathogen adhesion.

Tolerance to simulated gastrointestinal juice

The survival rate of LAB in the gastrointestinal (GI) system was assessed using the method of Millette et al.41 with slight modifications. Firstly, the pH of simulated gastric juice was adjusted to 3.0, while that of simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) was adjusted to 6.8 before autoclaving. Prior to testing, the bacteria were also washed three times with an equal volume of phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.0). The bacterial concentration was then adjusted to 109 CFU/mL, and after adding 1 mL of the bacterial suspension to 9 mL of simulated gastric fluid, incubation was performed for 2 h at 37 °C with continuous shaking at 200 rpm. This was followed by the transfer of 1 mL of the resulting mixture to 24 mL of SIF, and after a second incubation (3 h at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm), the gastrointestinal tolerance of LAB was assessed by comparing bacterial counts before and after gastrointestinal transit.

Whole genome sequencing and analysis

Bacteria cultured for 22 h were collected by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 min, and after being quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, they were sent to Majorbio Sequencing Center (Shanghai, China) on dry ice for whole genome sequencing and analysis. The genome was sequenced using a combination of the Illumina Hiseq 2500 and PacBio RS II single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing platforms42. The number of genes, gene functions, virulence factors and repressor genes were then analyzed using available software before performing gene function annotations with the NR and KEGG databases. Antimicrobial resistance genes were analyzed with the ResFinder software. In this case, gene function was compared using BLAST + software.

Statistical analysis

All tests were performed in triplicate, with the differences between treatments analyzed using 2-tailed Student’s t-tests in Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). When p ≥ 0.05, the difference is not significant; when p < 0.05, the difference is significant; and when p < 0.01, the difference is extremely significant.

Ethical approval

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Screening of bacterial isolates and identification

A total of eight Lactobacillus strains, screened from vaginal secretions, were able to inhibit G. vaginalis to varying degrees, with the size of the inhibitory zones produced by each strain shown in Table 1. Specifically, except for E08 and E11, the remaining six strains had nearly similar inhibitory potential. Through additional screening involving Candida albicans inhibition, it was found that only strain E09 could inhibit the second pathogen with inhibitory diameters of 1.30 ± 0.1 cm on agar plates. Therefore, E09 was selected as a candidate probiotic strain for subsequent experiments. Interestingly, the selected strain was also able to inhibit the growth of E. coli and S. enteritidis with inhibitory diameters of 1.13 ± 0.06 cm and 1.44 ± 0.02 cm, respectively. Finally, additional tests revealed that strain E09 could produce hydrogen peroxide, with its colonies turning blue on media containing horseradish peroxidase.

Table1.

Antibacterial effects of isolated LAB on G. vaginalis as indicated by the size of their zones of inhibition (in cm).

| LAB | Zone of inhibition, cm |

|---|---|

| E01 | 1.47 ± 0.15 |

| E04 | 1.40 ± 0.00 |

| E07 | 1.30 ± 0.00 |

| E08 | 1.03 ± 0.06 |

| E09 | 1.40 ± 0.00 |

| E10 | 1.33 ± 0.12 |

| E11 | 1.13 ± 0.12 |

| E12 | 1.23 ± 0.06 |

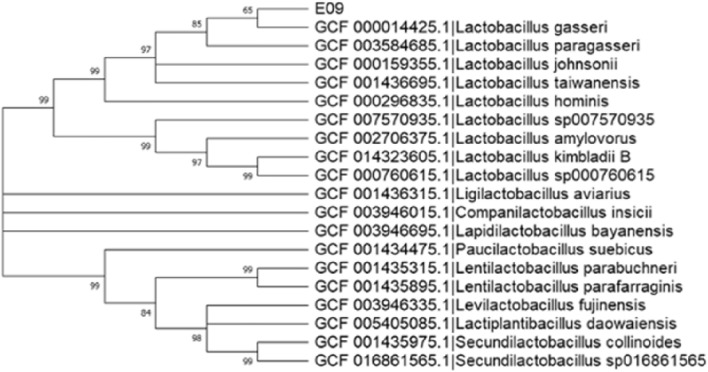

The 16S rRNA sequence of the strain was uploaded to the NCBI database (Genbank accession: OR945710), and based on BLAST comparison, it was found to be closely related to L. gasseri. Nineteen closely related strains were also selected, and their downloaded 16s rRNA sequences were used to construct a phylogenetic tree, based on the Neighbor-Joining method, using MEGA11.0 software (Fig. 1). Overall, strain E09 showed the highest homology to L. gasseri GCF 000,014,425, and hence, it was named L. gasseri VHProbi E09.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of L. gasseri VHProbi E09 based on 16S rRNA sequences.

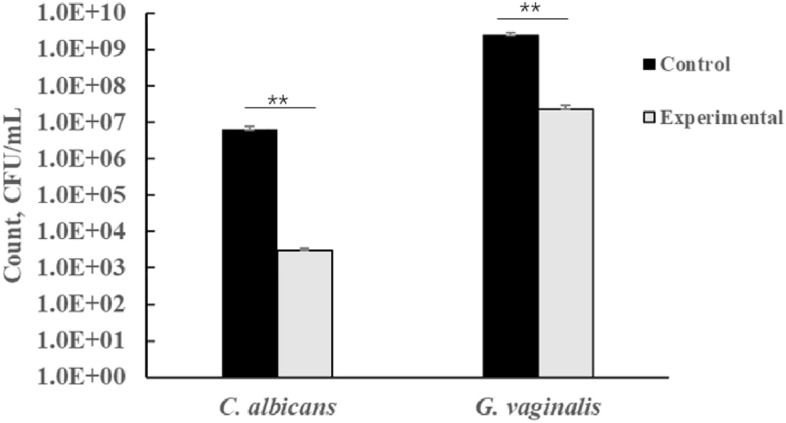

Inhibitory effects of L. gasseri VHProbi E09 against pathogens

Figure 2 shows the inhibitory effects of L. gasseri VHProbi E09 on the growth of G. vaginalis and C. albicans. For the G. vaginalis pathogen, after 24 h of incubation with L. gasseri VHProbi E09, the final bacterial load of 2.27 × 107 CFU/mL. Thus, compared with the control which had a bacterial load of approximately 2.43 × 109 CFU/mL, the results represented a 99.07% ± 0.26% inhibition of G. vaginalis. Regarding C. albicans, the control group had a bacterial load of approximately 6.17 × 106 CFU/mL, while the final bacterial load after adding L. gasseri VHProbi E09 was 2.97 × 103 CFU/mL, hence indicating an inhibition of 99.95% ± 0.01%.

Figure 2.

The inhibitory effects of L. gasseri VHProbi E09 against C. albicans and G. vaginalis by co-culture method. ∗ p < 0.05, ∗ ∗ p < 0.01.

Test of adhesion to vaginal epithelial cells

Adhesion is an important prerequisite for the colonization of probiotics, and in this set of experiments, L. gasseri VHProbi E09 was found to adhere strongly to primary vaginal epithelial cells. Specifically, after 2 h of incubation, 1.7 × 105 bacterial CFU could be detected inside each well containing vaginal epithelial cells, with this value indicating an adhesion index of 6.9 ± 1.0 CFU/cell. The adhesion ability of these bacteria highlights their potential to stay in the vagina for a long period of time during which they can exert effective probiotic effects.

L. gasseri VHProbi E09 also adhered strongly to Caco-2 cells. In this case, 6.07 ± 105 bacterial cells could be detected inside each well containing Caco-2 cells after 2 h of incubation. Thus, with an adhesion index of 2.43 ± 0.27 CFU/cell, the results suggested that these bacteria could remain in the gut for a long period of time, thereby making them effective in providing extended probiotic effects. In addition, the ability of intestinal Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG strain to adhere to Caco-2 cells was determined, but its adhesion index of 1.76 ± 0.22 CFU/cell suggested that it was less effective than L. gasseri VHProbi E09.

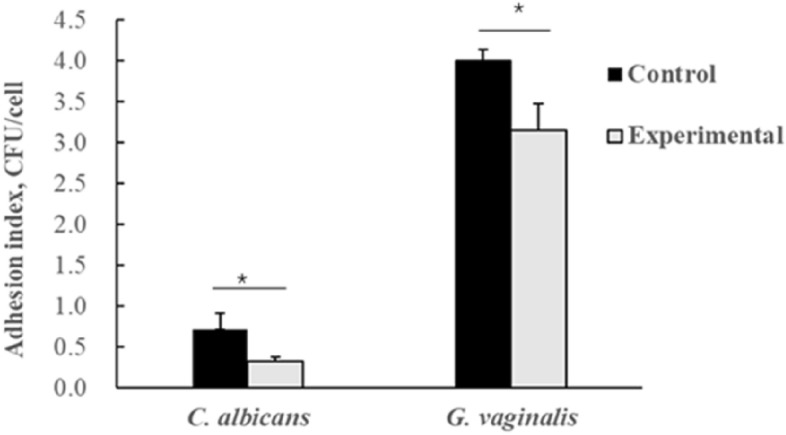

Inhibition of pathogen adhesion to vaginal epithelial cells

The ability of L. gasseri VHProbi E09 to reduce adhesion of C. albicans and G. vaginalis to vaginal epithelial cells is shown in Fig. 3. Overall, L. gasseri VHProbi E09 significantly inhibited G. vaginalis’s attachment to the epithelial cells (Fig. 3), with its adhesion index of 0.33 ± 0.05 CFU/cell being significantly lower than that of the control (0.71 ± 0.20 CFU/cell) (p < 0.05). Similarly, the inhibitory effect of L. gasseri VHProbi E09 against C. albicans adhesion, was also evident, and in this case, the adhesion index was 3.15 ± 0.33 CFU/cell, while that of the control was 4.00 ± 0.14 CFU/cell (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effects of L. gasseri VHProbi E09 on adhesion of C. albicans and G. vaginalis to vaginal epithelial cells. ∗ indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Tolerance to artificial GI juice

Table 2 shows the bacterial count before and after digestion with the GI fluids (artificial gastric fluid and artificial intestinal fluid). The results showed that L. gasseri VHProbi E09 had a higher survival rate in the simulated gastric and intestinal fluids as its initial inoculum decreased from 8.20 ± 0.01 log CFU/mL to a final count of 7.56 ± 0.02 log CFU/mL (p < 0.01). This decrease of 0.66 log CFU/mL was lower compared to that of L. rhamnosus GG (LGG) for which the bacterial load was reduced by 2.86 log CFU/mL after digestion with the artificial intestinal solutions. Thus, the results suggested that strain E09 had a higher tolerance to the digestive solutions than L. rhamnosus GG.

Table 2.

Bacterial count before and after digestion with artificial gastrointestinal solution (log CFU/mL).

| Strains | Initial count | After 2 h in simulated gastric juice | After 3 h in simulated intestinal fluid |

|---|---|---|---|

| E09 | 8.20 ± 0.01 | 8.22 ± 0.03 | 7.56 ± 0.02 |

| LGG | 8.94 ± 0.08 | 8.17 ± 0.03 | 5.31 ± 0.03 |

Whole genome analyses

The genome of L. gasseri VHProbi E09 was sequenced on the PacBio SMRT platform, and the whole genome sequence, with a 99.46% coverage, was then uploaded to NCBI database under GenBank and SRA accession numbers CP129028 and SRR27126921, respectively. The results revealed that L. gasseri VHProbi E09 had a circular chromosome of 1 864 621 bases and a GC content of 35.23%. In addition, 93 RNA genes and 1752 open reading frames (ORFs) were identified. Specifically, the latter, with an average length of 952.88 bp and a gene density of 0.94, accounted for 89.53% of the whole genome.

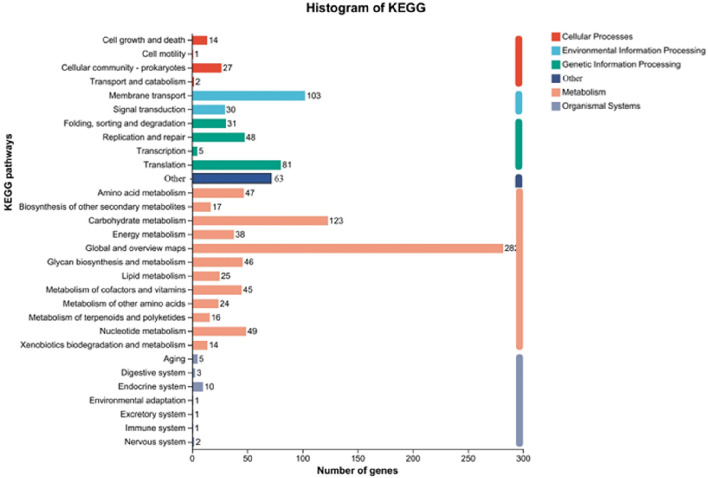

Analysis with the ResFinder software (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/) highlighted the absence of genes associated with antimicrobial resistance in L. gasseri VHProbi E09, while the Diamond comparison software further suggested that the isolate had no virulence factor secretion system and hence, may not secrete virulence factors. Annotation of coding genes against the KEGG database subsequently identified 1154 genes which accounted for 65.87% of the total genes (Fig. 4). In particular, 726 genes were involved in metabolism, 165 were involved in genetic information processing, 156 were associated with organismal systems, 133 were involved in environmental information processing, 44 were associated with cellular processes and 63 were involved in other processes. The coding genes were also compared against the NR database, and in this case, seven genes were found to be associated with adhesion. Of these, genes 0044, 0145, 0408 and 0880 were presumed to be associated with adhesion exoproteins, while genes 0878, 0882 and 0883 were presumed to encode adhesins. In addition, there were three genes related to bacteriocin, with gene 0474 which shared 100% similarity to the bacteriocin gene of Lactobacillus gasseri (Accession: WP_003647676), presumed to be a class III bacteriocin. Finally, genes 0542 and 0561 were presumed to encode bacteriocin immunity protein.

Figure 4.

KEGG-based annotation showing the pathways in which L. gasseri VHProbi E09 genes could be involved.

Discussion

Lactobacillus is generally recognized as the predominant bacterial group in the vagina where it maintains a balance in the microflora by secreting metabolites (such as lactic acid, bactericins, and H2O2) that inhibit the growth and adhesion of other microorganisms43,44. Therefore, Lactobacillus strains sourced from vaginal secretions are believed to more effectively colonize and contribute to a healthy vaginal environment. In this study, a Lactobacillus strain with potential probiotic effects was screened from vaginal secretions and identified as Lactobacillus gasseri based on 16s rRNA sequences. This is not surprising as numerous reports already present L. gasseri as a major group of vaginal lactobacilli45,46. The isolated strain, referred to as L. gasseri VHProbi E09, could inhibit the growth of C. albicans and G. vaginalis under static and dynamic co-culture conditions. In particular, it could produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) which is known to inhibit a range of pathogens including G. vaginalis, C. albicans and E. coli44,47,48. In this context, Eschenbach et al. noted that LAB species that produce H2O2 may enhance the nonspecific antimicrobial defence of the vaginal ecosystem49. Furthermore, whole genome analysis revealed that L. gasseri VHProbi E09 harbored three genes encoding bacteriocin, hence indicating its ability to metabolize bacteriocin to inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria.

Adhesion ability is crucial for lactobacilli to exert a probiotic role, but at the same time, it is a key process for pathogens such as G. vaginalis, C. albicans and E. coli which cause diseases by adhering to epithelial cells to form biofilms26,50,51. Therefore, by colonizing vaginal epithelial cells, LAB can impede the pathogens’ adhesion to the cells, thereby inhibiting their growth52–54. Genomic analysis and cell adhesion tests performed in this study showed that L. gasseri VHProbi E09 had strong adhesion ability to vaginal epithelial cells, and as such, it could inhibit the adhesion of Gardnerella and C. albicans to cells. In addition, whole genomic analysis predicted the safety of the isolated strain for human use. Hence, the results suggested that L. gasseri VHProbi E09 is a potential vaginal probiotic strain.

Given the significant in vitro inhibition of vaginal pathogens by L. gasseri VHProbi E09, future studies should focus on their mechanisms in in vivo models. Vaginal probiotics can prevent and treat vaginitis through oral and vaginal administration55,56. The adhesion capacity of L. gasseri VHProbi E09, along with the bacteriostatic substances it produces, suggest its enhanced effectiveness through direct vaginal action. Since vaginitis can be treated orally, this study also investigated the isolate’s gastrointestinal tolerance, intestinal cell adhesion and ability to inhibit intestinal pathogens. In this case, it was observed that of L. gasseri VHProbi E09 could inhibit the intestinal pathogens E. coli and S. enteritidis. Furthermore, it had better tolerance to gastric and intestinal fluids as well as better adhesion to intestinal Caco-2 cells compared with the well-known intestinal probiotic strain L. rhamnosus GG. Therefore, it is hypothesised that the strain could also exert its probiotic effects in the gut through oral administration.

In conclusion, in vitro experiments indicated that L. gasseri VHProbi E09, a hydrogen peroxide producer, could inhibit the adhesion of pathogenic bacteria to cells and tolerate gastrointestinal stress, thereby showing promise as a vaginal probiotic. These findings not only provide a theoretical basis for its later clinical studies, but also offer new ideas and opportunities for the treatment of vaginal-associated infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the reviewers who participated in the review, as well as MJEditor (www.mjeditor.com) for providing English editing services during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Jingyan Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review &editing draft. Kailing Li: Methodology, Data curation, Writing—original draft. Tishuang Cao: Methodology, Data curation. Zhi Duan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Re-sources, Data curation, Writing—review and editing, supervision, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in NCBI database. GenBank for 16s DNA is OR945710. GenBank and SRA accession numbers for the whole genome are CP129028 and SRR27126921. The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ravel J, Brotman RM. Translating the vaginal microbiome: gaps and challenges. Genome Med. 2016;8:35. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jespers V, et al. Quantification of bacterial species of the vaginal microbiome in different groups of women, using nucleic acid amplification tests. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton JP, Cadieux PA, Reid G. Improved understanding of the bacterial vaginal microbiota of women before and after probiotic instillation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:97–101. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.1.97-101.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid G, McGroarty JA, Tomeczek L, Bruce AW. Identification and plasmid profiles of Lactobacillus species from the vagina of 100 healthy women. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 1996;15:23–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiss H, et al. Vaginal Lactobacillus microbiota of healthy women in the late first trimester of pregnancy. BJOG Int. J. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 2007;114:1402–1407. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petricevic L, et al. Characterisation of the oral, vaginal and rectal Lactobacillus flora in healthy pregnant and postmenopausal women. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012;160:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovachev S. Obstetric and gynecological diseases and complications resulting from vaginal dysbacteriosis. Microb. Ecol. 2014;68:173–184. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrova MI, Lievens E, Malik S, Imholz N, Lebeer S. Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents that can promote various aspects of vaginal health. Front. Physiol. 2015;6:81. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mastromarino P, Vitali B, Mosca L. Bacterial vaginosis: A review on clinical trials with probiotics. New Microbiol. 2013;36:229–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amsel R, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am. J. Med. 1983;74:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg NKM. Bacterial Vaginosis. StatPearls; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutman RE, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Blume J. Evaluation of clinical methods for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2005;105:551–556. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000145752.97999.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swidsinski A, et al. Adherent biofilms in bacterial vaginosis. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2005;106:1013–1023. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183594.45524.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sobel JD. Pathogenesis and treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1992;14(Suppl 1):S148–S153. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.supplement_1.s148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobel JD, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 1998;178:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)80001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li T, Liu Z, Zhang X, Chen X, Wang S. Local probiotic Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii exhibit strong antifungal effects against vulvovaginal candidiasis in a rat model. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1033. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harriott MM, Lilly EA, Rodriguez TE, Fidel PL, Noverr MC. Candida albicans forms biofilms on the vaginal mucosa. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2010;156:3635–3644. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.039354-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neal CM, Kus LH, Eckert LO, Peipert JF. Noncandidal vaginitis: A comprehensive approach to diagnosis and management. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2020;222:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradshaw CS, Sobel JD. Current treatment of bacterial vaginosis-limitations and need for innovation. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;214(Suppl 1):S14–S20. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masone MC. Ibrexafungerp to treat acute vulvovaginal candidiasis. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021;18:638–638. doi: 10.1038/s41585-021-00522-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobel JD, Chaim W, Nagappan V, Leaman D. Treatment of vaginitis caused by Candida glabrata: Use of topical boric acid and flucytosine. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2003;189:1297–1300. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00726-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komesu YM, et al. Defining the relationship between vaginal and urinary microbiomes. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2020;222:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witkin SS, Linhares IM, Giraldo P. Bacterial flora of the female genital tract: Function and immune regulation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 2007;21:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reid G, et al. Microbiota restoration: Natural and supplemented recovery of human microbial communities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:27–38. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He Y, et al. Evaluation of the inhibitory effects of Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus crispatus on the adhesion of seven common lower genital tract infection-causing pathogens to vaginal epithelial cells. Front. Med. 2020;7:284. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cianci A, et al. Observational prospective study on Lactobacillus plantarum P 17630 in the prevention of vaginal infections, during and after systemic antibiotic therapy or in women with recurrent vaginal or genitourinary infections. J. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 2018;38:693–696. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1399992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murina F, Graziottin A, Vicariotto F, De Seta F. Can Lactobacillus fermentum LF10 and Lactobacillus acidophilus LA02 in a slow-release vaginal product be useful for prevention of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis?: A clinical study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014;48(Suppl 1):S102–S105. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemmerling A, et al. Phase 1 dose-ranging safety trial of Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05 for the prevention of bacterial vaginosis. Sexually Transm. Dis. 2009;36:564–569. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a74924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stapleton AE, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of a Lactobacillus crispatus probiotic given intravaginally for prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:1212–1217. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shamshu R, Vaman J, Nirmala C. Role of probiotics in lower reproductive tract infection in women of age group 18 to 45 years. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2017;6(2):671. doi: 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20170404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reznichenko H, et al. Oral intake of lactobacilli can be helpful in symptomatic bacterial vaginosis: A randomized clinical study. J. Lower Genital Tract Dis. 2020;24:284–289. doi: 10.1097/lgt.0000000000000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russo R, Superti F. Randomised clinical trial in women with Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Efficacy of probiotics and lactoferrin as maintenance treatment. Mycoses. 2019;62:328–335. doi: 10.1111/myc.12883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McInnes, P. Manual of Procedures for Human Microbiome Project Core Microbiome Sampling Protocol A, Version Number: 12.0 (ed National Institutes of Health (NIH), 2010).

- 34.Zhang J, Duan Z. Identification of a new probiotic strain, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum VHProbi(®) V38, and its use as an oral health agent. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13:1000309. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill GB, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Bacteriology of the vagina. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. Supplement. 1984;86:23–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao Y, Zhang X. Identification of antibacterial substances of Lactobacillus plantarum DY-6 for bacteriostatic action. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;8:2854–2863. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Li K, Bu X, Cheng S, Duan Z. Characterization of the anti-pathogenic, genomic and phenotypic properties of a Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus VHProbi M14 isolate. PloS ONE. 2023;18:e0285480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGroarty JA, Tomeczek L, Pond DG, Reid G, Bruce AW. Hydrogen peroxide production by Lactobacillus species: Correlation with susceptibility to the spermicidal compound nonoxynol-9. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:1142–1144. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.6.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck BR, et al. Whole genome analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from kimchi and determination of probiotic properties to treat mucosal infections by Candida albicans and Gardnerella vaginalis. Front. Microbial. 2019;10:433. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen P, et al. Screening for potential new probiotic based on probiotic properties and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Food Control. 2014;35:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.06.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Millette M, Nguyen A, Amine KM, Lacroix M. Gastrointestinal survival of bacteria in commercial probiotic products. Int. J. Probiot. Prebiot. 2013;8:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chin CS, et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGroarty JA. Probiotic use of lactobacilli in the human female urogenital tract. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 1993;6:251–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKloud E, et al. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a dynamic interkingdom biofilm disease of candida and Lactobacillus. mSystems. 2021;6:e0062221. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00622-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fettweis JM, et al. The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1012–1021. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mousavi E, et al. In vitro adherence of Lactobacillus strains isolated from the vaginas of healthy Iranian women. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. JCMA. 2016;79:665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGroarty JA, Reid G. Detection of a Lactobacillus substance that inhibits Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbial. 1988;34:974–978. doi: 10.1139/m88-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skarin A, Sylwan J. Vaginal lactobacilli inhibiting growth of Gardnerella vaginalis Mobiluncus and other bacterial species cultured from vaginal content of women with bacterial vaginosis. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. Sect. B Microbiol. 1986;94:399–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1986.tb03074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eschenbach DA, et al. Prevalence of hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species in normal women and women with bacterial vaginosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1989;27:251–256. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.251-256.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campana R, Federici S, Ciandrini E, Baffone W. Antagonistic activity of Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356 on the growth and adhesion/invasion characteristics of human Campylobacter jejuni. Curr. Microbiol. 2012;64:371–378. doi: 10.1007/s00284-012-0080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mappley LJ, Tchórzewska MA, Cooley WA, Woodward MJ, La Ragione RM. Lactobacilli antagonize the growth, motility, and adherence of Brachyspira pilosicoli: A potential intervention against avian intestinal spirochetosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:5402–5411. doi: 10.1128/aem.00185-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farnworth ER. The evidence to support health claims for probiotics. J. Nutr. 2008;138:1250s–1254s. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.6.1250S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenstein IJ, et al. Relationship between hydrogen peroxide-producing strains of lactobacilli and vaginosis-associated bacterial species in pregnant women. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1997;16:517–522. doi: 10.1007/BF01708235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saxelin M, Tynkkynen S, Mattila-Sandholm T, de Vos WM. Probiotic and other functional microbes: From markets to mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005;16:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mastromarino P, et al. Effectiveness of Lactobacillus-containing vaginal tablets in the treatment of symptomatic bacterial vaginosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009;15:67–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Recine N, et al. Restoring vaginal microbiota: biological control of bacterial vaginosis A prospective case-control study using Lactobacillus rhamnosus BMX 54 as adjuvant treatment against bacterial vaginosis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016;293:101–107. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3810-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in NCBI database. GenBank for 16s DNA is OR945710. GenBank and SRA accession numbers for the whole genome are CP129028 and SRR27126921. The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.