An official inquiry has been set up into allegations that the drug manufacturer Pfizer did not obtain official approval before testing a new drug on children during a meningitis epidemic in Nigeria five years ago.

The Nigerian doctor who supervised the clinical trial has said that his office backdated an approval letter and this may have been written a year after the study had taken place.

Pfizer, whose headquarters are in New York city, has admitted that the local ethics approval given to conduct the trial may not have been properly documented: “Pfizer takes this issue very seriously and is fully cooperating with the Nigerian authorities.”

In 1996 Pfizer sent a team to Kano in the north of Nigeria during an epidemic of meningococcal meningitis. To test the efficacy of its new antibiotic trovafloxacin (Trovan) they carried out an open label trial in 200 children, half of whom were given trovafloxacin and half the gold standard treatment for meningitis, ceftriaxone. Five of the children given trovafloxacin died, together with six who were given ceftriaxone. Pfizer said that 15000 people died during the epidemic.

The Washington Post has been investigating the trial and alleges that at least one child was not taken off the experimental drug and given the standard drug when it was clear that her condition was not improving—which is against ethical guidelines.

The newspaper also claims that Nigerian patients were not warned that animal studies had shown that drugs similar to trovafloxacin may cause joint damage, whereas US patients were told of the research in a subsequent trovafloxacin trial. The drug's licence was withdrawn in Europe because of liver toxicity and some deaths.

The letter granting ethical approval for the Pfizer trial was submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration in 1997 to support a licence application for trovafloxacin. However, Sadiq Wali, the medical director of the Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, told the Washington Post that the letter was false and the hospital had no ethics committee at the time of the study. Abdulhamid Isa Dutse, the doctor who oversaw the trial at the hospital, told the newspaper that it was “possible” that the approval letter was drafted up to a year after the trial.

The Nigerian health minister, Tim Menakaya, has now appointed a federal investigative panel to determine whether the trial was conducted legally and if so whether it was morally right.

The investigation has generated a lot of publicity in the Nigerian press. The newspaper Vanguard said: “The government has a duty to tell us whether our children were used as guinea pigs and, if so, who committed such criminality and who is liable.”

Charles Medawar, director of Social Audit, the UK pressure group that monitors the pharmaceutical industry, said: “This particular case looks to be very bad, but I hardly think it is untypical.”

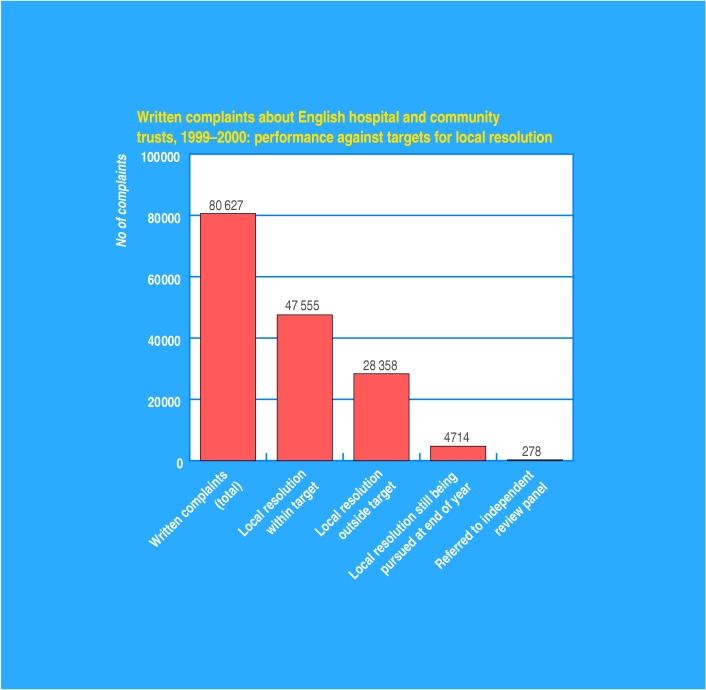

Figure.

Six out of 10 hospital complaints settled within four weeks

Sixty per cent of the 80000 complaints made against English hospital and community trusts were resolved locally within the performance target of four weeks, a Department of Health survey showed this week. The rest were resolved locally outside the target (35) or were still being pursued at the end of the year (5%). Almost 2000 patients (2.4) requested an independent review of their case, of whom 278 were granted one.