Abstract

The assembly of the alphavirus nucleocapsid core is a multistep event requiring the association of the nucleocapsid protein with nucleic acid and the subsequent oligomerization of capsid proteins into an assembled core particle. Although the mechanism of assembly has been investigated extensively both in vivo and in vitro, no intermediates in the core assembly pathway have been identified. Through the use of both truncated and mutant Sindbis virus nucleocapsid proteins and a variety of cross-linking reagents, a possible nucleic acid-protein assembly intermediate has been detected. The cross-linked species, a covalent dimer, has been detected only in the presence of nucleic acid and with capsid proteins capable of binding nucleic acid. Optimum nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking was seen at a protein-to-nucleic-acid ratio identical to that required for maximum binding of the capsid protein to nucleic acid. Identical results were observed when cross-linking in vitro assembled core particles of both Sindbis and Ross River viruses. Purified cross-linked dimers of truncated proteins and of mutant proteins that failed to assemble were found to incorporate into assembled core particles when present as minor components in assembly reactions, suggesting that the cross-linking traps an authentic intermediate in nucleocapsid core assembly. Endoproteinase Lys-C mapping of the position of the cross-link indicated that lysine 250 of one capsid protein was cross-linked to lysine 250 of an adjacent capsid protein. Examination of the position of the cross-link in relation to the existing model of the nucleocapsid core suggests that the cross-linked species is a cross-capsomere contact between a pentamer and hexamer at the quasi-threefold axis or is a cross-capsomere contact between hexamers at the threefold axis of the icosahedral core particle and suggests several possible assembly models involving a nucleic acid-bound dimer of capsid protein as an early step in the assembly pathway.

The nucleocapsid core (NC) of Sindbis virus (SINV), the prototypical alphavirus, is a 410-Å-diameter T = 4 icosahedron composed of an 11,703-nucleotide genomic RNA surrounded by 240 copies of a single nucleocapsid protein (CP) (22). Cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction analysis structures of several complete alphavirus virions have been generated (1, 11, 19). Examination of the NC within these particles demonstrates a series of pentameric and hexameric capsomeres that project ∼40 Å off of the core surface. Based on the size and location of the capsomeres, the C-terminal domain of the CP has been attributed to the density within these projections (1). The structure of the C-terminal protease domain of the CP of SINV has been solved to atomic resolution (5). Attempts at generating an atomic structure of the complete SINV and Ross River virus (RRV), or the NCs alone, have been unsuccessful (13; T. L. Tellinghuisen, R. J. Kuhn, and M. G. Rossmann, unpublished results). Structural information about the NC has been limited to the combination of the cryoelectron microscopy image reconstructions of complete virions and the numerous crystal structures of portions of CP. Modeling of the atomic structure of the SINV CP into the cryoelectron density of the RRV suggests a possible orientation of the protein within the capsomeres (1). This model is supported by recent work involving the fitting of the atomic structure of the C-terminal domain of the Semliki Forest virus CP into a 9-Å cryoelectron microscopy image reconstruction of the complete SFV virion, which demonstrates a similar orientation of the CP in the core (3; E. J. Mancini and S. D. Fuller, personal communication). The identification of a high-resolution structure of the NC of SINV or RRV is of paramount importance in understanding the mechanism of core assembly.

The mechanism of the alphavirus NC assembly, although extensively studied, is poorly understood. It is known from previous in vivo studies that immediately following translation and proteolysis, the CP is associated with the large subunit of the ribosome (12, 20). It then associates with genomic RNA and rapidly assembles into NCs (21). The rapidity of NC formation has made the identification of assembly intermediates difficult.

To circumvent the complexity of studying NC assembly in vivo, an in vitro assembly system for SINV core-like particles (CLPs) has been established using purified CP (24, 27). It was found that CLPs could be assembled in the in vitro system using a variety of single-stranded DNA or RNA substrates. Furthermore, CLPs produced by these systems closely resembled cytoplasmic CLPs purified from infected cells in size and shape when examined by negative-stain electron microscopy. Despite intensive investigation using these in vitro assembly systems, no intermediates in the NC assembly process have been observed using CP (residues 19 to 264) (24).

During the characterization of the in vitro assembly system, several CP truncations that failed to assemble particles but were competent for nucleic acid binding and incorporation into core particles were identified (24). Truncated CPs that lacked nucleic acid binding capability failed to incorporate into core particles. Additionally, no NC assembly was observed in the absence of nucleic acid, as had previously been observed (27). Since nucleic acid binding appears to be a requirement for NC assembly, analysis of the state of the CP bound to nucleic acid is very important. Based on analytical ultracentrifugation and size exclusion chromatography, the SINV CP is monomeric in solution, despite numerous crystallographic examples of dimeric forms of the protein (2, 4). Truncated or mutant proteins that fail to assemble core particles but retain nucleic acid binding properties may therefore identify intermediates in the assembly process. In the present study, the oligomerization of assembly-incompetent truncated and mutant CPs in the presence of nucleic acid was examined by the use of a variety of lysine-specific cross-linking reagents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SINV and RRV CPs and nucleic acids.

SINV and RRV CPs were expressed and purified as described previously (24). Truncations of the SINV CP were also expressed and purified as previously described (24). Proteins are identified by the abbreviation CP followed by the residues expressed in parentheses. Protein purity was typically 90 to 95% as estimated by silver stain sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and analytical sizing column analysis. All protein concentrations reported are based on absorbance at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 27,880 M−1 cm−1 for CP(19–264) and 22,190 M−1 cm−1 for CP(81–264). Concentrations based on extinction coefficients were confirmed by a protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) to validate the calculated extinction coefficients for the proteins. The standard synthetic 48-mer DNA oligonucleotide used in assembly assays was 5′-CCGTTAATGCATGTCGAGATATAAAGCATAAGGGACATGCATTAACGG-3′. Shorter oligonucleotides consisting of 18, 16, 14, 12, and 6 nucleotides were 3′ truncations of the standard assembly oligonucleotide. Transfer RNA substrates consisted of commercial preparations of ultrapure yeast tRNA (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). Viral genomic RNA consisted of purified and uncapped in vitro transcripts generated from the pToto64 SINV cDNA clone (18).

Nucleic acid binding.

Binding of various CPs to DNA oligonucleotides or tRNA was conducted as described below. Equal molar amounts of nucleic acid and protein (approximately 2 nmol of each) were mixed at room temperature in buffer A (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 100 mM potassium acetate, 1.7 mM magnesium acetate) with a reaction volume of 25 μl, unless otherwise noted. For concentration dependence experiments, DNA oligonucleotides were diluted in buffer A to the concentrations shown in Fig. 2 and added as equal volumes (12.5 μl) to 400-μg/ml CP samples (12.5 μl) and were incubated for 10 min. Mock nucleic acid-bound samples contained 12.5 μl of 1-mg/ml CP and 12.5 μl of buffer A. The samples were then treated as described below.

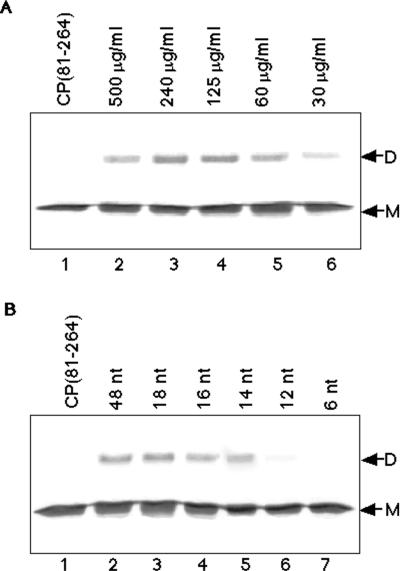

FIG. 2.

Nucleic acid concentration and length requirements for DMS cross-linking of CP(81–264). (A) Lane 1 demonstrates the electrophoretic mobility of CP(81–264) on SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) with Coomassie R-250 staining, with only monomeric protein evident (M). Lanes 2 to 6 represent decreasing amounts of the 48-mer assembly oligonucleotide mixed with a fixed amount of CP(81–264) in the presence of DMS. The electrophoretic mobilities of the monomeric (M) and dimeric (D) forms of CP(81–264) are indicated. Note that the optimum cross-linking efficiency is seen in lane 3. (B) Lane 1 is identical to lane 1 in panel A, showing the migration of CP(81–264) alone. Lanes 2 through 7 represent cross-linking of CP(81–264) with DMS in the presence of equal molar concentrations of 3′ truncations of the standard assembly oligonucleotide. Efficient cross-linking is observed in lanes 2 through 5. Only trace levels of dimeric CP are seen with the 12-mer oligonucleotide (lane 6), and no cross-linking is observed with the 6-mer oligonucleotide (lane 7). nt, nucleotides.

Cross-linking of CP.

Chemical reagents used for cross-linking analysis were dimethyl suberimidate (DMS), dimethyl pimelimidate (DMP), and disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). For cross-linking analyses, nucleic acid-bound or mock-bound CP(81–264) samples were cross-linked with DMS at room temperature. Initial titration of the amount of DMS required for maximal CP cross-linking was performed. For optimal cross-linking, DMS was added in two aliquots over the span of 1 h to reach a final concentration of 0.75 mM. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 200 mM glycine followed by a 15-min incubation. Conditions for crosslinking with DMP were identical to those used for DMS. Cross-linking with DSS was conducted similarly to that with DMS and DMP, except that DSS was added in a single aliquot to a final concentration of 10 μM and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min. Reactions with DSS were terminated by a 15-min incubation in the presence of 200 mM glycine. Where indicated, cross-linking reaction mixtures were treated with 1 U of RNase-free DNase I (Ambion, Austin, Tex.) following cross-linking reagent neutralization. Cross-linking conditions used with CP(19–264)L52D were identical to those described for CP(81–264). Cross-linking of CP was monitored by both SDS-PAGE on 12% polyacrylamide gels and size exclusion analysis using a Superdex 75 (10/30; 22-ml bed volume) analytical column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) equilibrated with buffer A.

Removal of nucleic acid from cross-linking reaction mixtures.

CP(81–264) at 1 mg/ml in 100 μl of buffer A was mixed at room temperature with 100 μl of a 1-mg/ml tRNA solution in buffer A. Samples were incubated for 10 min, and DMS was added in two aliquots over the span of 1 h to reach a final concentration of 0.75 mM. Following cross-linking, excess unreacted DMS was eliminated by the incubation of the reaction mixtures in the presence of glycine at a final concentration of 200 mM for 15 min. Samples were then treated with 2 μl of a 1-mg/ml stock of RNase A (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction mixtures were then brought to a final concentration of 1 M NaCl to remove residual nucleic acid from the proteins. Samples were then exchanged into buffer A by buffer exchange in Centricon-10 centrifugal concentrators (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.).

In vitro capsid assembly.

In vitro capsid assembly was performed as described previously (24). Briefly, equal molar amounts of CP and nucleic acid were mixed in a final volume of 100 μl in buffer A at room temperature. Typical reaction mixtures contained 50 μl of 1-mg/ml CP (1.8 nmol) and 50 μl of 1-mg/ml 48-base assembly oligonucleotide (2 nmol) or 50 μl of 500-μg/ml tRNA (1.8 nmol). The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and the products were assayed for the presence of CLPs as described below.

Cross-linking of in vitro-assembled CLP.

Following in vitro assembly of CLPs under the conditions described above, CLPs were purified by sucrose gradient sedimentation and concentrated by using Centricon-100 centrifugal concentrators to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml in buffer A. For cross-linking of purified CLPs, 50 μl of purified CLPs (approximately 1 mg/ml) was cross-linked and analyzed under conditions identical to those described for CPs bound to nucleic acid.

Incorporation of cross-linked dimers into CLP.

Following removal of nucleic acid and exchange into buffer A, CP(19–264)L52D or CP(81–264) cross-linking reaction mixtures were added (50 μl of 1 mg/ml stock) to wild-type CP(19–264) (50 μl of 1 mg/ml) at room temperature to obtain a final protein concentration of 1 mg/ml in a volume of 100 μl. Cross-linked protein stocks contained approximately 45% dimeric protein. The 48-mer assembly oligonucleotide was then added at 1 mg/ml in a volume of 100 μl. The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 10 min and then loaded onto 25% freeze-thaw sucrose gradients in buffer A. Samples were centrifuged at 38,000 rpm for 90 min in an SW-41 rotor (Beckman, Palo Alto, Calif.) at 4°C. Gradients were fractionated by hand into 1-ml aliquots, and samples were examined by Western blot analysis. For Western blot analysis, gradient fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham). The membranes were exposed to a polyclonal anticapsid rabbit antibody and then to a secondary anti-rabbit goat immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma). Blots were subjected to chemoluminescent detection using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham) and exposed to X-ray film.

Cross-link mapping.

The location of the cross-link was mapped using a variety of proteolytic techniques. CP(81–264), the minimum sequence of CP with which nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking was observed, was used in initial cross-link mapping experiments. The location of the cross-link observed in longer protein constructs and complete particles was mapped as described for CP(81–264). For trypsinization experiments, CP(81–264) cross-linking reaction mixtures were incubated for 4 h at 37°C with 40 ng of tolylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (Sigma). Following digestion, proteolytic fragments were examined by SDS-PAGE (15% polyacrylamide gels) and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. For endoproteinase Lys-C mapping experiments, CP(81–264) cross-linking reaction products were denatured and digested for 16 h at 37°C with 5 ng of sequencing-grade endoproteinase Lys-C (Boehringer Mannheim). Following digestion, proteolytic fragments were examined by electrophoresis on Tricine-SDS-PAGE gels (20% polyacrylamide) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. Proteolytic fragments were transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), and selected fragments were identified by amino-terminal protein sequencing. In all mapping experiments, non-cross-linked samples of CP served as a negative control.

Mutagenesis of lysine 250.

In vitro mutagenesis of lysine 250 to arginine (K250R) was performed by using the Quick Change mutagenesis system (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The manufacturer's standard procedure and conditions as described in the system literature were used. Mutagenesis was performed in a pGEM capsid gene carrier plasmid (pGEMCap; generously provided by Rushika Perera) and was followed by subcloning, using Pfu polymerase-based DNA amplification, into a suitable expression vector. All clones and mutants were confirmed by double-stranded DNA dideoxy sequencing using Sequenase PCR-based sequencing (Amersham). The mutant K250R protein was purified as described above for CP(19–264).

RESULTS

DMS cross-linking of CP(81–264) is nucleic acid dependent.

Preliminary research into the development of the Escherichia coli-expressed protein in vitro assembly system for SINV and RRV core particles suggested that nucleic acid binding was a required step in the assembly of the NC (24). Definition of the state of the CP bound to nucleic acid was of paramount importance in understanding the early stages of the capsid assembly mechanism. To examine the state of the CP bound to nucleic acid, the minimum nucleic acid binding form of the CP, CP(81–264), was incubated with various nucleic acid substrates and the binding-reaction products were analyzed using a variety of techniques.

Initial cross-linking experiments, designed to identify the state of CP(81–264) bound to nucleic acid, were performed with glutaraldehyde. Glutaraldehyde cross-linking of these binding-reaction products failed to generate a specific nucleic acid-dependent cross-linked species. Therefore, the use of more specific cross-linking reagents was investigated. Specific chemical cross-linkers are largely limited to lysine- and cysteine-specific reagents. Examination of the sequence of the SINV CP, which lacks any cysteines, suggested the use of lysine-specific cross-linking reagents. A variety of lysine-specific imidoesters were assayed for the ability to induce nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking of CP(81–264). Imidoester reagents of ∼11 Å were capable of generating covalent dimers of CP(81–264) in the presence of nucleic acid.

A nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking of CP(81–264) with DMS is shown in Fig. 1. In lane 2, CP(81–264) cross-linked with DMS in the absence of nucleic acid is seen as only a monomer. Cross-linking of CP(81–264) bound to the 48-mer assembly oligonucleotide with DMS demonstrated two species, a dimeric cross-linked form of the CP and non-cross-linked monomeric CP (lane 4). Western blot analysis of reaction products identical to those shown in Fig. 1 indicated that both the observed monomeric and dimeric CP forms were immunoreactive to anti-SINV CP antisera (data not shown). The maximum observed cross-linking of CP into dimer with DMS was approximately 45 to 50% of total input protein, based on visual estimation of SDS-PAGE gels. Addition of DMS in excess of the optimum established conditions failed to generate significantly greater amounts of dimeric protein but did induce the formation of higher-order nonspecific cross-linked species (data not shown). Additionally, truncations of the CP, incapable of binding nucleic acid, were not cross-linked into dimers using DMS in the presence or absence of nucleic acid (data not shown). The cross-linking efficiency was found to be equivalent across a wide range of protein concentrations from 2.5 μg/ml to 3.5 mg/ml.

FIG. 1.

Nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking of CP(81–264). Lanes: 1, electrophoretic mobility of CP(81–264) by SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 staining, with only monomeric CP evident (M); 2, CP(81–264) treated with DMS in the absence of nucleic acid; 3, CP(81–264) bound to an equal molar concentration of the 48-mer assembly oligonucleotide; 4, CP(81–264) bound to DNA, as in lane 3, but cross-linked with DMS [the presence of a dimeric form of CP(81–264) is evident (D)]; 5, sample identical to that in lane 3 but treated with RNase-free DNase I; 6, sample identical to that in lane 4 but treated with RNase-free DNase I. In lane 6, the dimeric form of CP(81–264) remains following nuclease treatment (D).

To demonstrate that the cross-link was between two protein molecules and not between CP and the DNA, products were treated with DNase I. Lanes 5 and 6 of Fig. 1 show the DNase I treatment of samples identical to those in lanes 3 and 4. DNase I treatment of cross-linked protein samples was unable to eliminate the observed dimeric form of the CP. Additional data suggested that the observed cross-link was not a CP-nucleic acid adduct, since only cross-linked species consistent with the size of a dimer of CP(81–264) could be generated with a range of nucleic acid sizes (see Fig. 2B).

To further demonstrate the specificity and relevance of the observed nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking, the nucleic acid requirements for cross-linking were examined in light of the previously observed requirements for in vitro NC assembly (24). Varying the amount of nucleic acid used in the CP(81–264) binding reactions prior to cross-linking with DMS demonstrated that the optimum cross-linking was observed with the same ratio of nucleic acid to protein required for optimum binding of CP(81–264) (Fig. 2A). More importantly, it was also the same as the optimum ratio of CP(19–264) protein to nucleic acid required for CLP assembly (Fig. 2A, lane 3). Cross-linking at 500 μg of oligonucleotide per ml (approximately 2 oligonucleotides per CP) was observed, but at suboptimum levels (lane 2). Cross-linking at 240 and 120 μg of oligonucleotide per ml (corresponding to approximately 1 and 0.5 oligonucleotide per CP, respectively) demonstrated the maximum observed cross-linking. This correlated well with previous estimates that a molar ratio of 1 to 2 CPs per 48-mer oligonucleotide was optimum for assembly of CLPs in vitro (24). Further dilution of the oligonucleotide (corresponding to 4 proteins per oligonucleotide and higher ratios) showed decreased cross-linking.

Study of the SINV in vitro assembly system indicated that a minimum length of oligonucleotide was necessary for CLP formation (24). To examine if this limitation for nucleic acid substrates existed for cross-linking of CP(81–264), a series of truncations of the 48-mer assembly oligonucleotide were assayed for their ability to induce the CP dimer. In Fig. 2B, analysis of these truncated assembly oligonucleotides in cross-linking reactions is presented. The standard assembly oligonucleotide (Fig. 2B, lane 2) served as a positive control for cross-linking. Truncations of the assembly oligonucleotide shorter than 14 nucleotides significantly reduced or eliminated the observed cross-linking of CP(81–264) (lanes 6 and 7). Therefore, a minimum length requirement for cross-linking was observed, and this paralleled the requirement seen for in vitro core assembly. tRNA and viral RNA, which are competent substrates for in vitro core assembly, were capable of binding CP(81–264), and identical cross-linking of the protein with DMS was observed (data not shown). In all circumstances, the requirements of nucleic acid for cross-linking were similar to previous results for in vitro CLP assembly (24).

Cross-linking is distance specific.

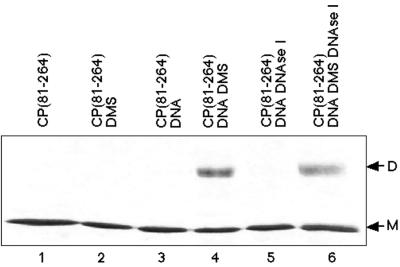

DMS has an 11.0-Å cross-linking distance and specificity for lysine residues. To demonstrate that the observed nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking was not an artifact of the reagent used, an 11.4-Å lysine-specific reagent (DSS) having a different cross-linking chemistry was selected. Figure 3, lanes 1 and 2, show the DMS nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking of CP(81–264). In lanes 3 and 4, the nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking of CP(81–264) with DSS is shown. Cross-linking with DSS was identical to that observed with DMS, although an increased cross-linking efficiency was observed. DSS was found to induce additional higher-order cross-linked species (trimers and tetramers); however, these species were not dilution independent and probably involved nonspecific crosslinking (data not shown). An additional cross-linking reagent with identical chemical mechanism and lysine specificity to DMS but with a shorter cross-linking distance (9.2 Å) was selected to examine if the reagent cross-link distance observed with DMS was critical for the observed cross-linking. DMP was found to be incapable of cross-linking CP(81–264) in the absence or presence of nucleic acid (Fig. 3, lanes 5 and 6) or under any conditions tested (data not shown). These observations suggested that reagent chemistry was not important for the observed cross-linking but that the cross-linking distance of the reagent was critical. It could be concluded that the observed cross-link occurred between two lysine residues approximately 11 Å apart on adjacent CPs associated with nucleic acid.

FIG. 3.

Reagent specificity and distance constraints of nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking of CP(81–264). Lanes 1, 3, and 5 demonstrate the electrophoretic mobility of CP(81–264 NCP) on SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) with Coomassie R-250 staining, with only monomeric protein evident (M). Lane 2 shows DMS (11 Å) cross-linking of CP(81–264) bound to the 48-mer assembly oligonucleotide, with dimeric CP(81–264) indicated (D). Lane 4 contains CP(81–264) cross-linked with DSS (11 Å) in the presence of the standard assembly oligonucleotide. Lane 6 shows the lack of cross-linking of CP(81–264) with DMP (9 Å) in the presence of the 48-mer oligonucleotide.

DMS cross-linking is observed in abortive core assembly reactions and assembled CLPs.

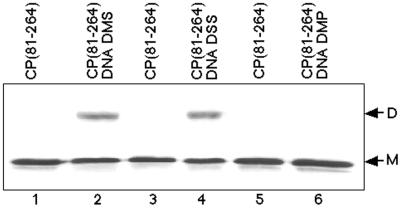

The cross-linking results observed with the truncated CP(81–264) were extended to consideration of assembly-defective CP(19–264) CP mutants. Extensive mutagenesis of the SINV CP and analysis of these mutant viruses has suggested several regions of the protein that appear to be involved in the NC assembly process (9, 10, 15, 16, 18, 25, 29). Several of these mutations cluster near the amino-terminal end of the CP in a region that has been proposed to form an α-helix (residues 38 to 55) based on modeling of the primary sequence into helical wheel plots (R. Perera, K. E. Owen, A. E. Gorbalenya, and R. J. Kuhn, unpublished data). The most striking feature of this putative helix is the presence of two conserved leucine residues at positions 45 and 52 (SINV amino acid numbering), which are arranged on the same face of the helix. These residues may form a leucine zipper interaction motif between two CPs. Mutation of leucine 52 to aspartic acid [CP(19–264)L52D] eliminated cytoplasmic NC formation in vivo. This mutant CP failed to assemble CLPs in the in vitro core assembly assay. However, the protein retained nucleic acid binding, as determined by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (data not shown). Nucleic acid binding properties and cross-linking of CP(19–264)L52D were similar to that observed for the truncated CP(81–264) and are shown in Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2. In addition, densitometry measurements of the products of multiple independent reactions of both proteins suggested that cross-linking efficiencies were identical (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking of full-length CPs. Lanes: 1, assembly-defective mutant CP(19–264)L52D, demonstrating the electrophoretic mobility of this protein on SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) in the absence of cross-linking; 2, CP(19–264)L52D bound to the 48-mer DNA oligonucleotide and cross-linked with DMS (a dimeric form of the CP is visible [D]); 3, SDS-PAGE migration of monomeric CP(19–264) wild-type protein in assembled CLPs; 4, identical CLPs to those seen in lane 3, but the CLPs were cross-linked with DMS, and a dimeric form of the CP is visible; 5, SDS-PAGE migration of monomeric RRV CP(1–270) wild-type protein in assembled CLPs; 6, identical RRV CLPs to those seen in lane 5, but the CLPs were cross-linked with DMS, and a dimeric form of the RRV CP(1–270) is detectable.

Cross-linking of in vitro-assembled CLPs was examined to demonstrate whether the observed cross-linking of truncated and assembly-defective mutant CPs represented a conformation of CPs seen in the assembled NC. In vitro-assembled CLPs were capable of being cross-linked with DMS (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4), whereas purified wild-type CP(19–264) in the absence of nucleic acid could not be cross-linked (data not shown). Cross-linking of particles with DMP generated no dimeric form of the CP (data not shown). Only dimeric forms of CP(19–264) were observed in particle cross-linking reactions, with no higher-order cross-links detectable. Additionally, in vitro-assembled CLPs of RRV were capable of nucleic acid-dependent crosslinking (lanes 5 and 6).

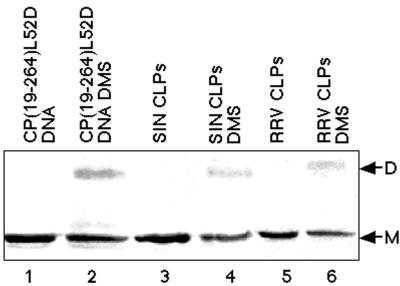

Cross-linked dimers can incorporate into CLPs.

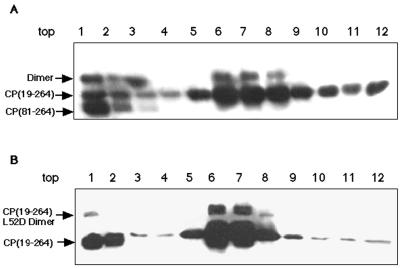

Since truncated and mutant CPs had been previously shown to incorporate into CLPs when present in in vitro assembly reaction mixtures as minor components (24), it was of interest to determine if cross-linked dimers of these proteins had a similar activity. CP(81–264) and CP(19–264)L52D dimers were produced as described above. Cross-linked dimers were then added to standard in vitro assembly reaction mixtures as minor components [0.5 nmol of CP(81–264) dimer, representing approximately 20% of the total input protein], and the reaction products were analyzed for the incorporation of dimeric forms of the CP into CLPs. Figure 5 shows a Western blot analysis of sucrose gradient sedimentation of core assembly/dimer incorporation reactions. In lanes 6 and 7 of Fig. 5A and lanes 6 and 7 of Fig. 5B, dimeric CPs can be seen cosedimenting with in vitro-assembled CLPs. It is interesting that the dimer form of CP(81–264) was preferentially incorporated into CLPs compared with the monomer form of the protein (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 1 and 6); however, the reason for this specificity is unknown. In control reactions where CLPs were first assembled and then incubated with identical amounts of cross-linked dimers to those used in the incorporation assays, no cosedimentation of dimer and CLP was observed (data not shown). This suggested that the dimer was incorporated in the core and was not aggregating or binding to the surface. The CP(19–264)L52D-containing CLPs sedimented at a position consistent with CP(19–264) in vitro-assembled CLPs, whereas particles containing CP(81–264) sedimented in a slightly altered position based on examination of the location of NC banding in sucrose gradients (data not shown). Examination of these assembly reaction mixtures and gradient-purified CLPs by electron microscopy suggested that the particles were identical in size and morphology to control CLPs (data not shown). No defects or aberrations in the structure of the dimer-incorporated CLPs were apparent at the level of negative-stain electron microscopy. The incorporation of the dimer into core assembly reaction mixtures strongly suggests that the cross-linked dimer is a trapped intermediate in the assembly process.

FIG. 5.

Capsid assembly in the presence of dimeric protein. (A) In vitro core assembly with SINV CP(19–264) and the 48-mer assembly oligonucleotide in the presence of cross-linked CP(81–264) assayed by sucrose density gradient sedimentation followed by fractionation and Western blot analysis. Numbers across the top of this panel correspond to gradient fractions presented top (fraction 1) to bottom (fraction 12). A peak corresponding to the position of gradient sedimentation of the in vitro-assembled CLPs can be clearly seen in fractions 6 through 8. Monomeric CP(81–264) is present only in the top three fractions of the gradient. Dimeric CP(81–264) can be seen in the top three fraction of the gradient, as well as comigrating with the assembled CLPs in fractions 6 through 8. (B) In vitro core assembly with SINV CP(19–264) and the 48-mer assembly oligonucleotide in the presence of cross-linked CP(19–264)L52D assayed by sucrose density gradient sedimentation followed by fractionation and Western blot analysis. All numbering of fractions is identical to that in panel A. CLPs sediment in a peak in fractions 6 through 8. CP(19–264)L52D dimer can be seen on the top of the gradient in fraction 1, as well as cosedimenting with CLPs in fractions 6 to 8. CLPs from the experiments in panels A and B were confirmed by negative-stain electron microscopy. In both cases, the CLPs had normal size and morphology.

Cross-link mapping.

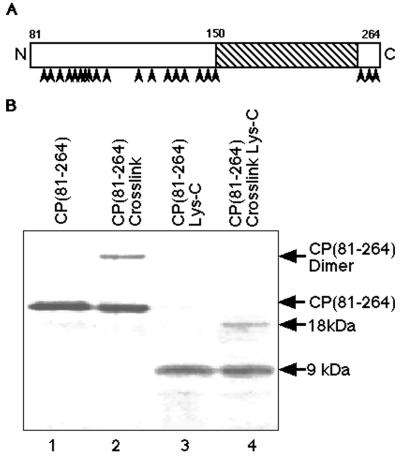

With the demonstration of functional relevance of the dimer based on the incorporation of cross-linked dimers into CLPs, the location of the cross-link was investigated. It had been shown previously that treatment of virus-isolated SINV CP with trypsin could produce a truncated CP containing residues 103 to 264 (23). Therefore, the CP(81–264) or CP(19–264) cross-linked dimer was treated with trypsin. The product of this treatment retained the cross-link and had a mobility on SDS-PAGE consistent with that of a dimer of approximately CP(103–264). This suggested that the observed cross-link was localized to the carboxyl-terminal region of CP from residues 103 to 264. Additional proteolysis experiments using endoproteinase Lys-C further localized the cross-link (Fig. 6A). Endoproteinase Lys-C treatment of CP(81–264) generated a single large fragment of approximately 9 kDa and numerous smaller fragments (Fig. 6B, lanes 3 and 4). Endoproteinase Lys-C digestion of CP(81–264) cross-linked dimers produced the digestion pattern of CP(81–264) plus an additional fragment of approximately 18 kDa. Amino-terminal sequencing of the 18-kDa band identified the position of this fragment in the CP, suggested that the observed cross-link was located between two 9-kDa fragments, and implicated lysine 250 as the side chain involved in the cross-link. Since the 9-kDa fragment contains only one lysine residue, the cross-linker had reacted with identical residues on two monomers. Similar proteolytic mapping of CP(19–264) cross-linked in assembled CLPs indicated the same lysine-250-to-lysine-250 cross-link. The presence of the cross-link in nucleic acid binding reaction mixtures and in assembled CLPs further indicated that the observed cross-linking of CP(81–264) was identical to the cross-linking observed in particles, suggesting that the nucleic acid-bound form of the truncated protein was an authentic intermediate in assembly. To further confirm the location of the cross-link, a substitution of lysine 250 to arginine was performed. Purified CP(19–264) and CP(81–264) carrying the lysine-250-to-arginine mutation lost the ability to cross-link in the presence of nucleic acid with DMS. Additional evidence for the importance of lysine 250 to the observed cross-linking can be found in the cross-linking of the RRV CP in assembled CLPs (Fig. 4, lane 6), since lysine 250 is conserved between SINV and RRV.

FIG. 6.

Endoproteinase Lys-C mapping of the location of the CP cross-linking. (A) Schematic of SINV CP(81–264) used in the mapping experiments. Endoproteinase Lys-C cleavage sites in the CP are indicated by arrowheads. The single large, 9-kDa peptide fragment produced by Lys-C digestion, consisting of amino acids 150 to 264, is indicated by hatching. (B) A Tricine-SDS-PAGE gel (20% polyacrylamide) stained with Coomassie blue R-250, demonstrating the results of endoproteinase Lys-C digestion of CP(81–264) and cross-linked CP(81–264). Lanes: 1, electrophoretic mobility of CP(81–264); 2, cross-linked CP(81–264) in the presence of DNA; 3, sample identical to that in lane 1, except that the samples were digested with endoproteinase Lys-C (the 9-kDa fragment, shown schematically in panel A, is indicated [9 kDa]); 4, sample identical to that in lane 2 but digested with endoproteinase Lys-C (the 9-kDa digestion product seen in lane 3 is visible in this lane, as is the dimeric form of this fragment [18 kDa]).

Location of the CP dimer.

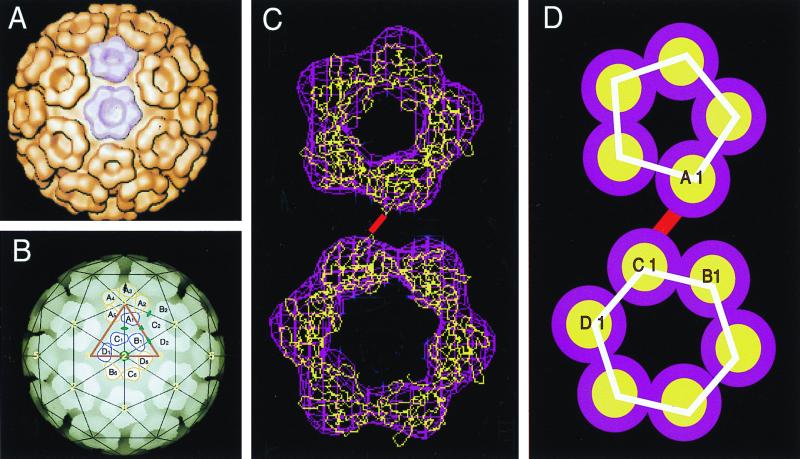

A model identifying residues 114 to 264 of the CP in the NC found in mature virions has been previously suggested (1). This model of the core structure was generated by fitting the atomic structure of the SINV CP(114–264) into the cryoelectron microscopy image reconstruction electron density of the NC of RRV (Fig. 7A to C). Examination of the orientation of CPs in this fit is consistent with the side chains of Lys-250 having a separation of 11 Å (Fig. 7C). In this cryoelectron microscopy fit model, the side chain of Lys-250 is projected into the intercapsomere space separating pentamers and hexamers (subunits A1 and C1 in Fig. 7B) and, although not shown, between adjacent hexamers (subunits B1 and D2 in Fig. 7B). It therefore seems likely that the dimer identified using chemical cross-linking is similar in orientation to CPs found in the mature virion (Fig. 7D).

FIG. 7.

Dimer model of the alphavirus nucleocapsid core. (A) A surface-shaded representation of the alphavirus NC as determined by cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction and viewed down a twofold axis (1). The pentamer and hexamer capsomeres can be clearly seen, with one pentamer and one hexamer colored in lavender. (B) Depth-cued representation of the NC with a superimposed T = 4 lattice. One icosahedral unit lies within the triangle and includes four CP monomers (A1, B1, C1, and D1). Yellow numbers identify the icosahedral axes, and green symbols label the pseudoaxes. (C) The electron density (lavender) of the pentamer and hexamer shown in panel A fitted with the atomic structure of residues 114 to 264 of the SINV CP (Cα backbone shown in yellow). A single loop from each monomer extends beyond the electron density and contains lysine 250 at its most distal point. Two lysine 250 residues that are separated by approximately ∼12 Å are joined by a red line that represents the chemical cross-link. (D) Schematic representation of the CP subunits shown in panel C. The cross-link shown in panel C links the two CPs denoted A1 and C1 into a dimer. The CPs denoted by B1 and D2 (not shown, but see panel B) represent a second dimer that would be found in the particle.

DISCUSSION

Investigation of alphavirus assembly has provided limited insight into the molecular details of the pathway, due at least in part, to the complexity of the in vivo environment. Structural approaches using cryoelectron microscopy and X-ray crystallography have provided substantial information concerning the organization of the mature virion, its internal NC, and the C-terminal domain of the CP. However, this represents a static picture of the virus and its components and has limited value in explaining the dynamic process of particle assembly. The complexity of examining capsid assembly in vivo has been circumvented by the development of an in vitro assembly system that utilizes purified CP and nucleic acid. The presence of an in vitro assembly system allows the examination of only the core assembly process separated from the other steps in virus assembly and other aspects of the virus life cycle.

During the development and characterization of the in vitro assembly system, the importance of nucleic acid binding in the early events of capsid assembly was identified (24). Several truncated and mutant forms of the SINV CP were shown to bind nucleic acid but not to assemble into core particles. These proteins were found to be competent to incorporate into core particles when added to wild-type assembly reaction mixtures, suggesting that the nucleic acid-bound form of these truncated proteins represented an early step in the assembly process. Therefore, identification of the form of the CP bound to nucleic acid was important in understanding the early steps in capsid assembly. For several virus assembly systems, chemical cross-linking has been used to identify an intermediate in particle assembly (14, 17, 30). Early chemical cross-linking experiments with SINV CLPs purified from virus particles and CP extracted from purified CLPs demonstrated that numerous cross-linking reagents could generate oligomers of the CP (6–8). Additionally, it was shown that purified CP and CLPs had different cross-linking patterns when compared. A preliminary arrangement of CPs in the NC was postulated based on their reactivity with cross-linking reagents of various cross-linking distances (6).

Analysis using cross-linking reagents to detect the oligomeric state of truncated CP bound to nucleic acid in in vitro assembly reactions led to some interesting observations. SINV CP(81–264), as well as CP(19–264)L52D, was found to be DMS-cross-linking competent only in the presence of nucleic acid under all conditions tested. This observation is supported by numerous experiments suggesting that the purified SINV CP is a monomeric protein in solution and that interaction with nucleic acid leads to oligomerization of the CP (24, 27). Nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking was found to occur only with lysine-specific cross-linking reagents having a cross-linking distance of approximately 11 Å, with shorter spanning reagents failing to generate any cross-linked products. Nucleic acid requirements for cross-linking were similar to previously published requirements for in vitro particle assembly, with both concentration and length limitations observed (24). These similarities between nucleic acid-dependent cross-linking and NC assembly suggest that the cross-linking species observed represents an intermediate in the assembly process. Additional evidence can be found in the observation that assembled CLPs contain the same cross-linked species as were observed with either the truncated or mutant CP. Similarly, RRV CLPs can be cross-linked into an analogous dimer, presumably because of the conservation of the lysine residue at that position of the CP. Further demonstration of the validity of the observed cross-linked dimer as an intermediate in the assembly pathway was provided by the incorporation of cross-linked dimers into assembled CLPs. The similarities between the requirements of cross-linking and particle assembly and the demonstration that identical dimers could be cross-linked in assembled CLPs or incorporated into particles after cross-linking strongly suggests that the observed cross-linking represents a valid NC assembly intermediate.

Examination of the location and distance of the observed cross-link in both CLPs and assembly-defective CPs in the presence of nucleic acid together with the previous model of the core provides some interesting insights (1). The most surprising feature observed when the fit of the crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of the SINV CP into the electron density of the cryoelectron microscopy reconstruction of RRV was examined was the fact that the side chain of lysine 250 projects outward from the pentameric and hexameric capsomeres of the core (Fig. 7). Thus, the CP dimer isolated using the DMS cross-linker is a pair of CPs that span the intercapsomere space and must be in contact at the base of the core or utilize nucleic acid to bridge across the two proteins.

The pentamer and hexamer capsomeres, which project ∼40 Å from the surface of the NC, have been modeled to contain the C-terminal domain of the CP (residues 114 to 264) (1). The remaining N-terminal residues of the CP would form the base and interior of the NC together with the genome RNA. The first 80 amino acids of the N-terminal region have 13 arginines and 3 lysines and are therefore expected to line the interior of the NC in contact with the negatively charged genome RNA. Indeed, Wengler has suggested that binding of nucleic acid to this region results in a conformational change, allowing further assembly to occur (26). Within the N-terminal 80 residues is a sequence of approximately 20 residues that can be modeled as an α-helix and plays a role in the assembly of the NC (Perera et al., unpublished). Deletions and point mutants in this α-helix seriously affect core assembly in vivo and block assembly in vitro. It has also been shown through molecular genetic experiments that much of the N terminus, excluding the putative helix region, can be removed and particles can still be produced, demonstrating significant plasticity in this region of the protein (10).

Based on the previous structure and molecular genetic experiments, one possible assembly pathway for the NC was the preassembly of capsomeres followed by the recruitment of RNA. The binding of RNA to the highly basic N terminus permitted the close approach of the N-terminal α-helices that then oligomerized to join the capsomeres to form the core. However, despite extensive investigation, no free capsomeres have been identified in the in vitro reaction mixtures or with CP alone (24, 27, 28). The cross-linking data presented in this paper suggest that rather than capsomeres, the initial assembly intermediate is that of a dimer bound to nucleic acid that spans the intercapsomere space. Two chemically identical dimers, A-C and B-D, would be sufficient to build the T = 4 icosahedral nucleocapsid (Fig. 7D), although the nature of CP oligomerization following dimer formation is unknown. This model of assembly matches the observed experimental data, which previous models, based on capsomere pre-assembly and subsequent oligomerization, do not. It is also analogous to the assembly of several plant viruses, most notably cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (30). However, in cowpea chlorotic mottle virus, intercapsomere dimers can form in the absence of nucleic acid.

Through the use of cross-linking reagents and assembly-defective mutant and truncated CPs, a potential artificially trapped assembly intermediate has been identified. The biological activity of the cross-linked dimer of these assembly-defective CPs has been demonstrated by the incorporation of these cross-linked species into CLPs using the in vitro assembly system. The mapping of the cross-link to lysine 250 and the examination of the location of this residue in the model of the NC suggests that the model represents, at least in part, the structure of the in vitro-assembled core. Although the cross-link at lysine 250 permits one to model the orientation of the CP in the dimeric state, the site and nature of the dimer interface have yet to be resolved. Additionally, the site and role of nucleic acid binding in capsid dimerization are unclear. The identification of cross-linked dimers of the SINV CP has led to new insights and to the generation of novel models for the assembly of the alphavirus NC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Thomas J. Smith for valuable assistance in development of cross-linking conditions. Assistance in protein sequence analysis and protease mapping from Mary Bower is also acknowledged. The gift of pGEMcap plasmid from Rushika Perera is acknowledged. Additionally, critical discussions with Michael Rossmann, Sergei Pletnev, Suchetana Mukhopadhyay, Rushika Perera, Chris Jones, Manoj Kumar, and Ranjit Warrier are gratefully acknowledged.

This research was supported by Public Health Service grant GM56279 from the National Institutes of Health. Additional funding from the Lucille Markey Foundation for structural studies at Purdue University is acknowledged. T.L.T. was supported, in part, by NIH biophysics training grant GM98296.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheng R H, Kuhn R J, Olson N H, Rossmann M G, Choi H-K, Smith T J, Baker T S. Nucleocapsid and glycoprotein organization in an enveloped virus. Cell. 1995;80:621–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90516-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi H-K, Lee S, Zhang Y-P, McKinney B R, Wengler G, Rossmann M G, Kuhn R J. Structural analysis of Sindbis virus capsid mutants involving assembly and catalysis. J Mol Biol. 1996;262:151–167. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi H-K, Lu G, Lee S, Wengler G, Rossmann M G. The structure of Semliki Forest virus core protein. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1997;27:345–359. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199703)27:3<345::aid-prot3>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi H-K, Tong L, Minor W, Dumas P, Boege U, Rossmann M G, Wengler G. Structure of Sindbis virus core protein reveals a chymotrypsin-like serine proteinase and the organization of the virion. Nature. 1991;354:37–43. doi: 10.1038/354037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi H K, Tong L, Minor W, Dumas P, Boege U, Rossmann M G, Wengler G. Structure of Sindbis virus core protein reveals a chymotrypsin-like serine proteinase and the organization of the virion. Nature (London) 1991;354:37–43. doi: 10.1038/354037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coombs K, Brown D T. Organization of the Sindbis virus nucleocapsid as revealed by bifunctional cross-linking agents. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:359–371. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90657-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coombs K, Brown D T. Topological organization of Sindbis virus capsid protein in isolated nucleocapsids. Virus Res. 1987;7:131–149. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(87)90075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coombs K M, Brown D T. Form-determining functions in Sindbis virus nucleocapsids: nucleosomelike organization of the nucleocapsid. J Virol. 1989;63:883–891. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.883-891.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsell K, Griffiths G, Garoff H. Preformed cytoplasmic nucleocapsids are not necessary for alphavirus budding. EMBO J. 1996;15:6495–6505. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsell K, Suomalainen M, Garoff H. Structure-function relation of the NH2-terminal domain of the Semliki Forest virus capsid protein. J Virol. 1995;69:1556–1563. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1556-1563.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller S D, Berriman J A, Butcher S J, Gowen B E. Low pH induces swiveling of the glycoprotein heterodimers in the Semliki Forest virus spike complex. Cell. 1995;81:715–725. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glanville N, Ulmanen J. Biological activity of in vitro synthesized protein: binding of Semliki Forest virus capsid protein to the large ribosomal subunit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;71:393–399. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison S C, Strong R K, Schlesinger S, Schlesinger M J. Crystallization of Sindbis virus and its nucleocapsid. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:277–280. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ktistakis N T, Kao C-Y, Lang D. In vitro assembly of the outer shell of bacteriophage ø6 nucleocapsid. Virology. 1988;166:91–102. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H, Brown D T. Mutations in an exposed domain of Sindbis virus capsid protein result in the production of noninfectious virions and morphological variants. Virology. 1994;202:390–400. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S, Owen K E, Choi H K, Lee H, Lu G, Wengler G, Brown D T, Rossmann M G, Kuhn R J. Identification of a protein binding site on the surface of the alphavirus nucleocapsid protein and its implication in virus assembly. Structure. 1996;4:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nassal M, Rieger A, Steinau O. Topological analysis of the hepatitis B virus core particle by cysteine-cysteine cross-linking. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:1013–1025. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90101-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen K E, Kuhn R J. Identification of a region in the Sindbis virus nucleocapsid protein that is involved in specificity of RNA encapsidation. J Virol. 1996;70:2757–2763. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2757-2763.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paredes A M, Brown D T, Rothnagel R, Chiu W, Schoepp R J, Johnston R E, Prasad B V V. Three-dimensional structure of a membrane-containing virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9095–9099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Söderlund H. Kinetics of formation of Semliki Forest virus nucleocapsid. Intervirology. 1973;1:354–361. doi: 10.1159/000148864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Söderlund H, Ulmanen I. Transient association of Semliki Forest virus capsid protein with ribosomes. J Virol. 1977;24:907–909. doi: 10.1128/jvi.24.3.907-909.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss J H, Strauss E G. The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:491–562. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.491-562.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strong R K, Harrison S C. Proteolytic dissection of Sindbis virus core protein. J Virol. 1990;64:3992–3994. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3992-3994.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tellinghuisen T L, Hamburger A E, Fisher B R, Ostendorp R, Kuhn R J. In vitro assembly of alphavirus cores by using nucleocapsid protein expressed in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1999;73:5309–5319. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5309-5319.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss B, Geigenmüller-Gnirke U, Schlesinger S. Interactions between Sindbis virus RNAs and a 68 amino acid derivative of the viral capsid protein further defines the capsid binding site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:780–786. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.5.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wengler G. The mode of assembly of alphavirus cores implies a mechanism for the disassembly of the cores in the early stages of infection. Arch Virol. 1987;94:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF01313721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wengler G, Boege U, Wengler G, Bischoff H, Wahn K. The core protein of the alphavirus Sindbis virus assembles into core-like nucleoproteins with the viral genome RNA and with other single-stranded nucleic acids in vitro. Virology. 1982;118:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wengler G, Wengler G, Boege U, Wahn K. Establishment and analysis of a system which allows assembly and disassembly of alphavirus core-like particles under physiological condition in vitro. Virology. 1984;132:401–412. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wengler G, Würkner D, Wengler G. Identification of a sequence element in the alphavirus core protein which mediates interaction of cores with ribosomes and the disassembly of cores. Virology. 1992;191:880–888. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90263-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X, Fox J M, Olson N H, Baker T S, Young M J. In vitro assembly of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus from coat protein expressed in E. coli and in vitro-transcribed viral cDNA. Virology. 1995;207:486–494. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]