Abstract

Context:

Contributing to the evidence base, by disseminating findings through written products such as journal articles, is a core competency for public health practitioners. Disseminating practice-based evidence that supports improving cardiovascular health is necessary for filling literature gaps, generating health policies and laws, and translating evidence-based strategies into practice. However, a gap exists in the dissemination of practice-based evidence in public health. Public health practitioners face various dissemination barriers (eg, lack of time and resources, staff turnover) which, more recently, were compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Program:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention (DHDSP) partnered with the National Network of Public Health Institutes to implement a multimodal approach to build writing capacity among recipients funded by three DHDSP cooperative agreements. This project aimed to enhance public health practitioners’ capacity to translate and disseminate their evaluation findings.

Implementation:

Internal evaluation technical assistance expertise and external subject matter experts helped to implement this project and to develop tailored multimodal capacity-building activities. These activities included online peer-to-peer discussion posts, virtual writing workshops, resource documents, one-to-one writing coaching sessions, an online toolkit, and a supplemental issue in a peer-reviewed journal.

Evaluation:

Findings from an informal process evaluation demonstrate positive results. Most participants were engaged and satisfied with the project’s activities. Across eight workshops, participants reported increased knowledge (≥94%) and enhanced confidence in writing (≥98%). The majority of participants (83%) reported that disseminating evaluation findings improved program implementation. Notably, 30 abstracts were submitted for a journal supplement and 23 articles were submitted for consideration.

Discussion:

This multimodal approach serves as a promising model that enhances public health practitioners’ capacity to disseminate evaluation findings during times of evolving health needs.

Keywords: capacity building, dissemination, evaluation, public health practitioners, technical assistance

A core competency for public health practitioners (“practitioners”) is to contribute to the evidence base for improving health.1 Dissemination, which involves communicating findings from evidence-based interventions to the audience through planned channels and strategies,2 represents one skill that fulfills this competency. As the mortality rates of chronic diseases, specifically cardiovascular disease (CVD), continue to rise in the United States,3 the importance of practitioners disseminating their findings and recommendations remains critical.4 Such findings can expand the evidence base, thus increasing the availability of evidence for other professionals to learn about innovative public health efforts to address CVD.4,5 Effective dissemination not only advances progress in public health research and practice but also bridges the research practice gap.6 Nevertheless, a gap persists in disseminating practice-based evidence in the public health field.6,7

Practitioners working in health departments, teaching institutions, and other settings face barriers to dissemination; commonly reported challenges include competing demands, schedules, and time limitations.8-11 Additionally, these practitioners may lack resources, systems, frameworks, or scientific writing skills needed to disseminate their practice-based findings to the broader public health community.10-12 They may not have access to the literature, familiarity with the traditional publication submission process, or writing confidence, all of which contribute to publication barriers.11,13,14 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these challenges, leading to reduced health systems capacity and diversion of staffing and resources to the pandemic response.15,16 With all these barriers, practitioners may be discouraged from writing consistently, may be inclined to adopt a hurried dissemination approach, or may neglect dissemination altogether.9,10 These obstacles can hinder the dissemination of evidence that is valuable for filling literature gaps, generating health policies and laws, and translating evidence-based strategies into practice.6

Writing workshops, writing retreats, and peer support are considered effective ways to bolster dissemination capacity among practitioners.17-19 These activities allow practitioners to establish the skills needed to initiate, implement, and complete a writing task. Other promising approaches to strengthen capacity include training, use of tools, technical assistance (TA), assessment and feedback, and incentives.2 These strategies not only equip practitioners with effective dissemination skills but also make these skills a part of their routine practice.2,17

To address the gap in dissemination, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention (DHDSP) partnered with the National Network of Public Health Institutes (NNPHI) through a cooperative agreement to implement a multimodal approach aimed at enhancing practitioners’ writing capacity to effectively translate and disseminate their evaluation findings. In collaboration with NNPHI, training materials and resources were developed for practitioners in state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments that received funding through the DP18-1815 (Improving the Health of Americans Through Prevention and Management of Diabetes and Heart Disease, and Stroke), DP18-1816 (Well-Integrated Screening and Evaluation for Women Across the Nation; WISEWOMAN), and DP18-1817 (Innovative State and Local Public Health Strategies to Prevent and Manage Diabetes, Heart Disease, and Stroke) cooperative agreements.20 Through these three cooperative agreements, DHDSP supported 111 recipients in implementing CVD-related public health strategies.20 This project provided CDC-funded public health practitioners (hereinafter “recipients”) the opportunity to hone scientific writing skills. Our strategy in building writing capacity and bridging dissemination gaps could benefit other practitioners, state and local health departments, and public health funders aiming to replicate this approach.

Program

DHDSP provides evaluation support to recipients to help them complete their cooperative agreement requirements.20 More specifically, evaluation support aims to help recipients with their evaluations, performance measures, and evaluation deliverables. Despite the well-established TA structure, disseminating evaluation findings proved challenging for recipients during the COVID-19 pandemic. A one-size-fits-all approach to building public health capacity is not likely to be effective.2,15 For this reason, it is necessary to use different modalities to meet the needs of recipients, especially since recipients differed in their writing capacity.

Recognizing this, DHDSP and NNPHI developed a comprehensive writing support project to supplement the TA structure.20 The project team implemented tailored capacity-building activities including the distribution of The Writing System21 textbook, online peer-to-peer discussion posts, writing workshops, resource documents, one-to-one writing coaching sessions, an online toolkit, and a journal supplement. The content conveyed during these activities aligned with The Writing System21 framework and was available to all 111 recipients, though participation was voluntary. The partnerships, seven capacity-building activities, and evaluation methods used in the multimodal approach are outlined below.

Partnerships

The project team consulted and collaborated with DHDSP evaluation TA providers and external partners to implement this project. NNPHI identified experienced consultants to provide subject matter expertise (SME) on writing, graphic design, health equity, data visualization, and online toolkit development. Additionally, the team regularly collaborated with the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors (NACDD), an organization representing state, local, and territorial health departments, to gather information from health department staff about their highest priority needs. We engaged a diverse set of partners to develop, tailor, and deliver high-quality content to meet recipients’ needs.

Multimodal capacity-building activities

Multimodal capacity-building comprised seven activities: distribution of The Writing System textbooks, online peer-to-peer discussion posts, writing workshops, writing resource documents, one-to-one writing coaching sessions, virtual toolkit, and submission to a journal supplemental issue. The Writing System21 textbook, which taught techniques on how to write more productively and efficiently, was provided by NNPHI at no cost to recipients. Weekly discussion posts on the recipients’ online awards management platform (AMP) provided writing tips and an opportunity for peer-to-peer information exchange on ways to overcome writing challenges. In addition to facilitating peer-to-peer discussions, AMP was designed for recipients to access program resources, request TA, connect across their program(s), and submit required deliverables. The team offered 60- to 90-minute virtual writing workshops—led by writing, data visualization, and health equity SMEs—designed to engage and expand recipients’ knowledge of scientific writing fundamentals. To identify topics and tailor the workshops to meet recipients’ needs, the project team consulted with evaluation TA providers and NNPHI. Table 1 includes an overview of workshop topics. Zoom polls and chat functions were used to make the sessions interactive.

Table 1.

Writing Workshop and Resource Document Topics

| Workshop # |

Workshop Topic | Workshop Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Defining Your Audience | To identify potential audiences for evaluation findings and learn a new style of writing management, to make the process more efficient and less daunting. |

| 2 | Using the Sentence Outlining Technique | To increase writing efficiency using a sentence outline technique to gather information, develop an outline, and get buy-in during the draft stages of writing. |

| 3 | Revising and Editing | Two-part series to enhance writing efficiency using a phased approach to: edit for organization; coherence, clarity, conciseness, and readability; and proofread. |

| 4 | Managing Writing Projects | To describe writing project management, including planning for timelines, staffing, and deliverable components. |

| 5 | Presenting at Conferences | To provide guidance on developing abstracts, creating presentations, and delivering oral presentations for online and hybrid conference environments. |

| 6 | Writing With a Health Equity Lens | To offer guidance on practical ways to incorporate a health equity lens into writing and analysis, provide resources and best practices, and demonstrate application of a health equity lens to relevant examples. |

| 7 | Data Visualization | To provide guidance on applying data visualization techniques to create clear messages for audiences. |

| 8 | Disseminating Evaluation Findings | To explore the various document types that could be used to showcase evaluation findings and offered ideas for writing and developing products based on data availability. |

| Resource Document # |

Document Topic | Document Objective |

| 1 | Steps for the Journal Publication Process | To provide guidance on the steps to submit a written product for publication in a peer-reviewed journal. |

| 2 | Determining Authorship and Contributor Order | To provide guidance for determining authorship order associated with group authorship. |

| 3 | Tips for Applying a Health Equity Lens to Evaluative Writing | To provide tips on how to apply a health equity lens when writing for evaluation. |

| 4 | Scoping Your Document | To provide tips on how to focus documents—from progress reports to peer-reviewed articles—in terms of the document’s purpose, audience, and length. |

| 5 | Resources for Conference Abstracts | To provide tips on how to submit conference abstracts and information about conferences relevant to evaluation work. |

| 6 | Creating an Annotated Bibliography | To provide guidance on the utility of annotated bibliographies in developing their written products. |

| 7 | Deciding Where to Publish: Journal Identification Tips | To provide tips for identifying journals to publish written products. |

| 8 | Dissemination of Evaluation Findings | To provide tips on the various mechanisms to consider for disseminating evaluation findings. |

Resource documents conveyed actionable tips in a short, easy-to-digest format, covering topics like the “Journal Publication Process” and “Dissemination of Evaluation Findings” (Table 1). Topic areas were identified based on evaluation TA provider input and, in some instances, complemented and supplemented writing workshop content. To ensure that the writing workshops and resource documents were accessible to all recipients, materials were posted to AMP.

For personalized support, writing SMEs offered virtual, 45-minute, one-to-one coaching sessions to help recipients develop effective written dissemination products, and recipients could participate in multiple sessions. The sessions emphasized editing, outlining, and writing techniques from The Writing System21 textbook.

Furthermore, we used a content creation platform to create an online interactive toolkit, which provided an engaging summary of the writing workshops and resource documents. The toolkit will continue to support recipients in developing dissemination products even after their cooperative agreement funding ends.

Lastly, a supplement was developed with the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice (JPHMP) to offer recipients the opportunity for peer-reviewed publication and to advance practice-based evidence that supports cardiovascular health. All recipients, regardless of participation in the multimodal activities, were invited to submit their funded work to JPHMP for consideration for the journal supplement. Once invited to submit a manuscript for the supplement, additional TA was provided to authors to help strengthen their submissions. SMEs offered a series of one-to-one writing coaching sessions, with session no. 1 focused on planning and analysis, session no. 2 on editing for content and style, and session no. 3 on writing revision guidance. Author teams could also join a two-part data visualization workshop that guided authors on creating graphics for their manuscript.

Implementation

To evaluate how the project’s multimodal activities enhanced capacity, the team conducted an informal process evaluation to assess recipients’ engagement and satisfaction with the activities, perceived writing knowledge and readiness, and benefits of disseminating evaluation findings.

Data sources

The virtual writing workshop Zoom polls and chats primarily helped the writing SMEs address recipient questions in real time and informed the development of activities. We also used the Zoom poll and chat responses from December 1, 2020, to June 23, 2022, to glean qualitative and quantitative information about the workshops. Zoom poll questions asked during writing workshops anonymously assessed participants’ self-reported writing confidence, writing knowledge gained, and perceived benefits from disseminating their evaluation findings. Open-ended responses from the workshop chats offered insights on participant satisfaction.

NACDD’s Evaluation Peer Network recipient survey, fielded in 2022, included quantitative and open-ended questions, with 60 state-based participants providing anonymous responses. This survey assessed recipients’ evaluation TA needs and captured recipients’ feedback on DHDSP TA efforts, including the writing workshops.

Anonymous testimonials from recipients who participated in these workshops and writing coaching sessions, and feedback from writing and data visualization SMEs, were gathered by NNPHI from emails to explore satisfaction in the multimodal activities.

Usage metrics for the writing workshops and resource documents were pulled from the number of views on the AMP platform from December 1, 2020, to September 13, 2023. For the toolkit, content performance metrics22 were accessed via the built-in analytics on the content creation platform. The analytics exported data from April 10, 2023, to August 2, 2023. Lastly, the number of writing coaching sessions from October 1, 2021, to November 30, 2023, were tracked using an Excel spreadsheet.

Journal supplement abstract submission forms provided details on the distribution of abstracts by cooperative agreement, geography, Health and Human Services (HHS) region,23 article type, and DHDSP programmatic strategy (ie, community-clinical linkages, clinical quality measures, team-based care). A review process involved independent scoring by a team of reviewers, comprising the project team and cooperative agreement SMEs, using scoring criteria developed by the project team and JPHMP. Afterwards, the team of reviewers joined in a facilitated discussion on abstract scores to reach consensus.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated, and an informal content analysis was conducted on these data sources. Quantitative data were analyzed and visualized in Excel 2019. Emerging themes from the content analysis included engagement, satisfaction, knowledge, writing confidence, perceived improvement in writing and benefits of disseminating findings, and opportunities to write (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of Themes From Informal Content Analysis

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| Engagement | Participation in the activities, views, and active interaction with the content. |

| Satisfaction | Feedback received after participating in the activities. |

| Knowledge | Participants’ perceived improvement in writing skills and knowledge. |

| Writing Confidence | Participants’ perceived belief about their ability to write. |

| Perceived Improvement in Writing and Benefits of Disseminating Findings | Participants’ perceived improvement in scientific writing skills and perceived benefits from dissemination. |

| Opportunities to Write | Increase in participants’ opportunities to write and disseminate evaluation findings in a supported environment. |

Evaluation

Since December 2020, the project team implemented seven multimodal capacity-building activities. This approach resulted in the following outputs: 72 The Writing System textbooks distributed, 66 online peer-to-peer discussion posts, 8 writing workshops, 8 writing resource documents, 75 one-to-one writing coaching sessions, 1 virtual toolkit, and 1 journal supplemental issue.

Engagement

Participants’ engagement in the writing workshops increased over time, peaking during the health equity (129 logins) and data visualization (132 logins) workshops. Similarly, the health equity–focused resource document created to accompany the workshop was the most viewed resource document on AMP (201 views), while the most viewed workshops on AMP were “Defining Your Audience” (286 views) and “Using the Sentence Outlining Technique” (285 views).

Recipients engaged with the writing SME in 12 one-to-one writing coaching sessions. Recipients used coaching sessions for guidance on a range of dissemination products, including infographics, brief reports, manuscripts, and fact sheets. Additionally, recipients attended 40 sessions focused on writing and editing their evaluation deliverables.

Since the virtual launch of the toolkit in April 2023, the project team tracked recipient engagement. Analytic metrics showed that the toolkit had 176 unique visitors, 486 document visits, and an average visit time of 4 minutes and 54 seconds for the second quarter of the year. Pages of the interactive tool kit with the highest time per page included “Workshop 7: Data Visualization” (10:57), “Workshop 3: Revising and Editing” (10:07), “Workshop 6: Writing With a Health Equity Lens” (5:53), and “Resources Page 2: Disseminating Your Work” (5:23).

Satisfaction

Recipients had positive impressions on the writing workshops, as illustrated by a respondent of the NACDD survey who stated, “the writing webinars were very helpful [and] would like more of those.” Other recipients expressed their gratitude for the workshop series and thought the “series was excellent” and informative. Recipients who partook in the one-to-one coaching sessions also expressed their positive feedback; for example one recipient stated, “We just completed a fantastic one-to-one session with [writing SME] and we were very grateful and excited for all the feedback we received.”

Knowledge

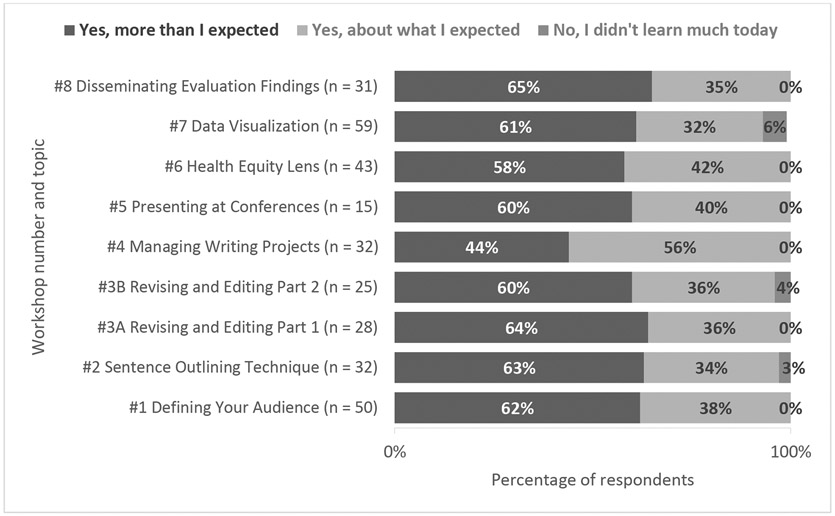

When asked the following Zoom poll question across eight workshops, “Do you feel like you’ve learned something from today’s workshop,” most participants answered that they learned more than expected or about what they expected from the writing workshops (≥94%; Figure 1). Nearly two-thirds of participants reported learning more than expected about “Disseminating Evaluation Findings” (65%), with a participant expressing appreciation for “the examples we work through on these calls.”

Figure 1.

Cumulative Zoom Poll Response Data on Writing Knowledge Gained

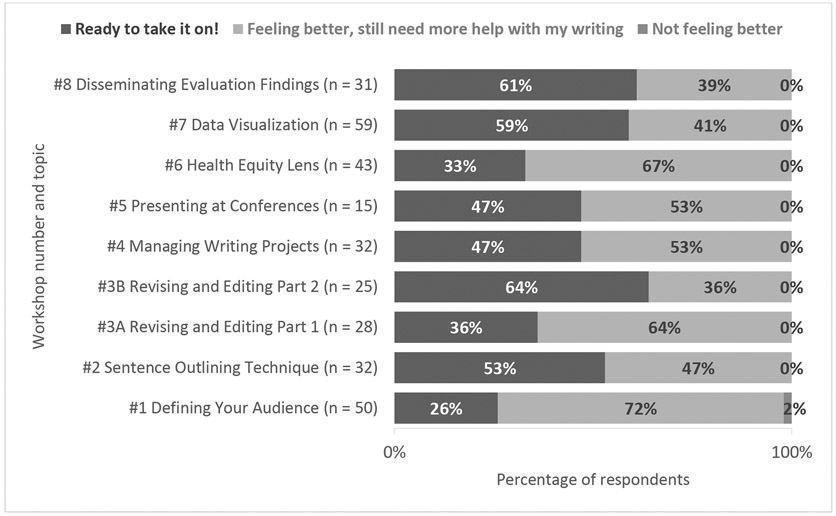

Writing confidence

Most participants answering the Zoom poll question across eight workshops, “How do you feel about writing after today’s workshop,” reported readiness to start writing or were feeling better about writing after attending the writing workshop (≥98%; Figure 2). The workshops that resulted in the highest respondents’ perceived confidence to start writing included “Revising and Editing—Part II” (64%), “Disseminating Evaluation Findings” (61%), and “Data Visualization” (59%). During the latter workshop, recipients exclaimed in the chat that they were “excited to apply this to a presentation I’m working on right now!” and the SME who led the workshop “made working with data exciting for a non-evaluator.”

Figure 2.

Cumulative Zoom Poll Response Data on Participants’ Writing Confidence

Perceived improvement in writing and benefits of disseminating findings

The writing SME commented on the improved quality of dissemination products after one-to-one coaching sessions. In one instance, the writing SME noted that after a second round of coaching, one recipient’s product had significantly improved, and the recipient exclaimed “we’re excited to revise this product!”

During the final workshop on dissemination of evaluation findings, when recipients were asked, “What benefits have you seen from disseminating your work so far,” 30 of 36 participants reported that disseminating evaluation findings improved program implementation. Fewer participants reported increased media attention (n = 3, 8%) and large number of hits/views (n = 2, 6%) as other benefits of dissemination.

Opportunities to write

While publication was not a requirement for all three cooperative agreements, DP18-1817 recipients were required to submit a publication-ready manuscript to DHDSP as one of their evaluation deliverables. The JPHMP supplement provided a supportive opportunity for publication across the cooperative agreements. A total of 30 submissions were received through a call for abstracts for the JPHMP supplement. The abstracts represented a diverse array of topics aligned with DHDSP programmatic strategies and represented each of the three cooperative agreements (Table 3). From the 30 abstracts submitted, 27 were invited to submit a manuscript (four author teams declined the invitation).

Table 3.

Distribution of Abstracts Submitted for the JPHMP Supplement by Cooperative Agreement, Geography, Health and Human Services Region, Article Type, and Division Programmatic Strategy (n = 30)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Cooperative Agreement | |

| 1815 | 6 (20) |

| 1816 | 5 (17) |

| 1817 | 18(60) |

| Both 1815 and 1817 | 1 (3) |

| Geography | |

| Urban | 6 (20) |

| Rural | 6 (20) |

| Statewide | 14(47) |

| Mix (statewide, urban/rural counties, mix of FQHCs across state) | 3 (10) |

| Tribal/indigenous | 1 (3) |

| HHS Regiona,b | |

| 1 | 4 (13) |

| 2 | 3 (10) |

| 3 | 7 (23) |

| 4 | 4 (13) |

| 5 | 4 (13) |

| 6 | 0 (0) |

| 7 | 2 (7) |

| 8 | 0 (0) |

| 9 | 5 (17) |

| 10 | 1 (3) |

| Article Type | |

| Research full report | 9 (30) |

| Research brief report | 3 (10) |

| Research brief/practice brief report | 1 (3) |

| Practice full report | 8 (27) |

| Practice brief report | 7 (23) |

| Case study | 2 (7) |

| DHDSP Programmatic Strategyb | |

| Community-clinical linkages | 11(37) |

| Clinical quality measures | 8 (27) |

| Team-based care | 5 (17) |

| Mix (mix of programmatic strategies) | 6 (20) |

Abbreviations: DHDSP, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention; FQHC, Federally Qualified Health Center; HHS, Health and Human Services.

HHS Regional Offices: https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/iea/regional-offices/index.html.

Percents may not equal 100 due to rounding.

JPHMP received 23 manuscripts for consideration for the CDC supplement. The supplement will be populated with briefs, reports, and case studies that report on DHDSP programmatic and evaluation strategies to advance cardiovascular health in various settings. The supplement will have two volumes to accommodate the number of submissions. Patanian, the author of this supplement’s editorial, further breaks down the general attributes of the collection of manuscripts and dives deeper into the various strategies as they are implemented in the field.24

Activities including one-to-one coaching sessions and a data visualization workshop were offered to JPHMP author teams to support their opportunity to write and publish. Author teams participated in 23 one-to-one coaching sessions with the writing SMEs. Approximately 13 author teams participated in the 2-day data visualization workshop. Those who attended thought the workshop was “excellent” and “very engaging” and appreciated how this workshop can help them develop their data visualization skills for evaluation dissemination.

Discussion

This project demonstrated positive results because we tailored multimodal activities to recipients’ needs. Most recipients were engaged in and satisfied with the multimodal activities. Findings also demonstrate that the activities both enhanced recipients’ knowledge and confidence and improved writing and dissemination. The toolkit was an effective way to package the content from the multimodal activities, specifically the writing workshops and resource documents. The toolkit and the JPHMP supplement were the culmination of our multimodal activities.

We were intentional about accepting as many abstracts as possible for the JPHMP supplement and then offered writing coaching sessions to support recipients through the peer-review process. This helped maximize the number of author teams from each of the three cooperative agreements to develop high-quality publications that expand the evidence base for strategies that support cardiovascular health. The large volume of high-quality abstracts we received for the journal supplement may suggest the potential influence of the multimodal approach on enhancing recipients’ scientific writing skills. Furthermore, we developed content specifically to enhance recipients’ capacity to write with a health equity lens. The project’s popular health equity–focused workshop and resource document positioned authors to write using a health equity lens; some of these articles highlight programs that served populations disproportionately affected by CVD. Offering different types of activities through a multimodal approach, while also tailoring those activities, set recipients up for success. This enabled recipients to generate practice-based evidence to inform strategies or frameworks, which can be used by practitioners and researchers looking to advance cardiovascular health.

It is important to recognize the role training and TA played in ensuring the skills and knowledge needed to meaningfully disseminate findings and share lessons learned to promote and improve public health.7,25 The most successful approaches to building capacity are likely to be multifaceted,2 as a core set of activities can provide practitioners with a toolbox to improve their dissemination efforts. Multimodal approaches can also offer a structure to sustain improvements in writing skills and dissemination.17 Writing and dissemination skills should not only be a core competency in public health, but these skills are especially important during times of evolving health needs.15,26 The Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity also provided virtual writing support to their recipients,17 mirroring our success and highlighting the viability of virtual capacity building for writing. We view this project as a way to offer health departments and tribal organizations the tools to enhance the impact of their results in their jurisdictions and to ensure that the capacity to disseminate findings effectively remains in place even after funding ends.

Limitations

It remains uncertain if the views of recipients participating in the activities and responding to the NACDD survey accurately reflect those of all 111 funded recipients, as participation in the multimodal activities was optional. The project’s activities were exclusive to recipients funded through the three cooperative agreements, thus limiting the generalizability of findings, and not capturing the perspectives of all practitioners. We conducted a process evaluation using TA-related data and gathered feedback to assess and improve our support to recipients. Our findings, which are not formal research or evaluation, should be interpreted cautiously. The information we collected was sufficient for the purpose of improving DHDSP’s TA approach—to support recipients’ capacity to develop publications and other dissemination products that describe successes, challenges, and noteworthy activities that resulted from their evaluation projects—under three cooperative agreements.

Implications for Policy & Practice.

With time constraints and competing priorities, practitioners may not have the necessary time to disseminate their findings. To support practitioners’ dissemination efforts and advance opportunities to publish, partnerships with public health organizations may help build writing capacity and address practitioners’ specific dissemination challenges, including dedicated writing time. Furthermore, practitioners can explore alternative written products (e.g., blog posts) to manuscripts to reduce time burden.

Tailoring and delivering a multimodal set of writing support activities may comprehensively build practitioners’ writing capacity, foster the development and completion of manuscripts and written products, and provide a structure for sustained improvements in writing and dissemination skills.

Dissemination outlets, like sponsored journal supplements, can create a dedicated space to highlight program contributions and may increase the published literature on CVD, thereby contributing to the overall knowledge base. Building practice-based evidence is critical for both informing public health planning and developing effective public health programs and interventions to help reduce the burden of CVD.

Recognizing variation in scientific writing capacity among practitioners, it is important to meet practitioners where they are and work toward building their self-efficacy and skills to disseminate their evaluation findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff from the National Network of Public Health Institutes (NNPHI), Alida Austin, BA, Julia Blesser, MS, MSPH (formerly with NNPHI), Shakiera Causey, PhD, Oscar Espinosa, MA, Christopher Kinabrew, MPH, MSW, and Dana Rosenberg, MPH, BSN, RN, for collaborating on the development and implementation of this project. We thank all the subject matter experts, and our internal and external partners, for their consultation, guidance, and technical support on the topic areas and content provided. We thank the Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention program recipients funded through DP18-1815, DP18-1816 (WISEWOMAN), and DP18-1817 cooperative agreements who participated in the project’s multimodal activities. We would also like to thank Michael Schooley, MPH, and Joanna Elmi, MPH, for their leadership and championing this project. Additionally, we thank Miriam Patanian, MPH, for her involvement in this project and review of this manuscript.

This work was supported by funds awarded to the National Network of Public Health Institutes through the cooperative agreement OT18-1802, Strengthening Public Health Systems and Services Through National Partnerships to Improve and Protect the Nation’s Health (award #6 NU38OT000303-04-02), from the Center for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

No protocol approval by an ethics committee was needed to conduct this project.

Contributor Information

Amber Scott, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE), Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Myles Bostic, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; ASRT, Inc., Atlanta, Georgia.

Meera Sreedhara, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Cherokee Nation Operational Solutions, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Jennifer McAtee, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Cherokee Nation Operational Solutions, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Jasmin Minaya-Junca, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Marla Vaughan, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Public Health Foundation. About the core competencies for public health professionals. Accessed November 21, 2023. http://www.phf.org/programs/corecompetencies/Pages/About_the_Core_Competencies_for_Public_Health_Professionals.aspx.

- 2.Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Green LW. Building capacity for evidence-based public health: reconciling the pulls of practice and the push of research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39(1):27–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. About Multiple Cause of Death, 1999–2020. CDC WONDER. Published 2022. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neupane D, Cobb LK, Hall B, et al. Building research capacity within cardiovascular disease prevention and management in low- and middle-income countries: a collaboration of the US centers for disease control and prevention, the lancet commission on hypertension group, resolve to save lives, and the world hypertension league. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2021;23(4):699–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen MH, Neupane D, Cobb LK, et al. Global cardiovascular disease prevention and management: a collaboration of key organizations, groups, and investigators in low- and middle-income countries. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22(8):1293–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(2):102–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huston SL, Porter A. State and local health departments: research, surveillance, and evidence-based public health practices. Prev Chronic Dis. 2023;20:E86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salas-Lopez D, Deitrick L, Mahady ET, Moser K, Gertner EJ, Sabino JN. Getting published in an academic-community hospital: the success of writing groups. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):113–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redelfs AH, Aguilera J, Ruiz SL. Practical strategies to improve your writing: lessons learned from public health practitioners participating in a writing group. Health Promot Pract. 2019;20(3):333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crosswaite C, Curtice L. Disseminating research results—the challenge of bridging the gap between health research and health action. Health Promot Int. 1994;9:289–296. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novick LF, Moore JB. The importance of publications by public health practitioners: a new tool. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(2):93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMullen TP, Mandelbaum J, Myers K, Brightharp C, Kavanaugh K, Hicks S. Expanding opportunities for data dissemination through collaborative writing teams in public health practice settings. Health Promot Pract. 2021;23(4):566–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayden J. Writing for publication 101. Health Promot Pract. 2000;1(1):21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duff D. Writing for publication. Axone (Dartmouth, NS). 2001;22(4):36–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zemmel DJ, Kulik PKG, Leider JP, Power LE. Public health workforce development during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a qualitative training needs assessment. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(5):S263–S270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alperin M, Bekemeier B. Regional public health training centers: an essential partner in workforce development. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(Supplement 5):S199–S202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavinghouze SR, Kettel Khan L, Auld ME, et al. From practice to publication: the promise of writing workshops. Health Promot Pract. 2022;23(1_suppl):21S–33S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiebe N, Pratt H, Noel N Writing retreats: creating a community of practice for academics across disciplines. J Res Admin. 2022;54(1):37–65. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cable CT, Boyer D, Colbert CY, Boyer EW. The writing retreat: a high-yield clinical faculty development opportunity in academic writing. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(2):299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention’s Program Development and Services Branch and Evaluation and Program Effectiveness Team Writing Group. Funding state and local health departments and tribal organizations to implement and evaluate cardiovascular disease public health strategies: a collaborative approach. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2024;30(4)(supp):S1–S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham D, Graham J, Lussos R The Writing System: A Step-by-Step Guide for Business and Technical Writers. 3rd ed. Preview Press; 2020:320 pages. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bloemen J Our Foleon analytics metrics explained. Foleon. Published 2023. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://help.foleon.com/hc/en-us/articles/11335926444945-Our-Foleon-Analytics-metrics-explained. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Office of Intergovernmental and External Affairs (IEA). Regional Offices. HHS.gov. Published July 10, 2006. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/iea/regional-offices/index.html.

- 24.Patanian M. Sharing results from the field - tracking and monitoring clinical measures: examples of practice- based evidence from recipients of CDC’s heart disease and stroke prevention funding. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2024;30(4)(supp):S15–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derman RJ, Jaeger FJ. Overcoming challenges to dissemination and implementation of research findings in under-resourced countries. Reprod Health. 2018;15(S1):86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valladares LM, Riegelman RK, Albertine S. Writing in public health: a new program from the association of schools and programs of public health. Public Health Rep. 2018;134(1):94–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]