Most cases of chronic viral hepatitis are caused by hepatitis B or C virus. Hepatitis B virus is one of the commonest chronic viral infections in the world, with about 170 million people chronically infected worldwide. In developed countries it is relatively uncommon, with a prevalence of 1 per 550 population in the United Kingdom and United States.

The main method of spread in areas of high endemicity is vertical transmission from carrier mother to child, and this may account for 40-50% of all hepatitis B infections in such areas. Vertical transmission is highly efficient; more than 95% of children born to infected mothers become infected and develop chronic viral infection. In low endemicity countries, the virus is mainly spread by sexual or blood contact among people at high risk, including intravenous drug users, patients receiving haemodialysis, homosexual men, and people living in institutions, especially those with learning disabilities. These high risk groups are much less likely to develop chronic viral infection (5-10%). Men are more likely then women to develop chronic infection, although the reasons for this are unclear.

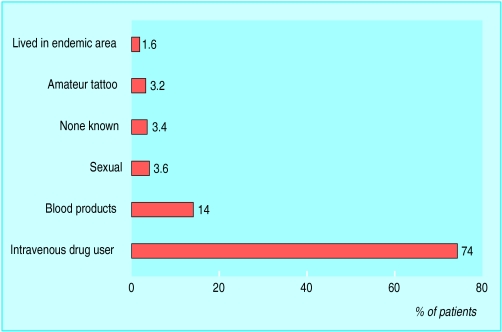

Up to 300 million people have chronic hepatitis C infection mainly worldwide. Unlike hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C infection is not mainly confined to the developing world, with 0.3% to 0.7% of the United Kingdom population infected. The virus is spread almost exclusively by blood contact. About 15% of infected patients in Northern Europe have a history of blood transfusion and about 70% have used intravenous drugs. Sexual transmission does occur, but is unusual; less than 5% of long term sexual partners become infected. Vertical transmission is also unusual.

Presentation

Chronic viral liver disease may be detected as a result of finding abnormal liver biochemistry during serological testing of asymptomatic patients in high risk groups or as a result of the complications of cirrhosis. Patients with chronic viral hepatitis usually have a sustained increase in alanine transaminase activity. The rise is lower than in acute infection, usually only two or three times the upper limit of normal. In hepatitis C infection, the γ-glutamyltransferase activity is also often raised. The degree of the rise in transaminase activity has little relevance to the extent of underlying hepatic inflammation. This is particularly true of hepatitis C infection, when patients often have normal transaminase activity despite active liver inflammation.

Hepatitis B

Most patients with chronic hepatitis B infection will be positive for hepatitis B surface antigen. Hepatitis B surface antigen is on the viral coat, and its presence in blood implies that the patient is infected. Measurement of viral DNA in blood has replaced e antigen as the most sensitive measure of viral activity.

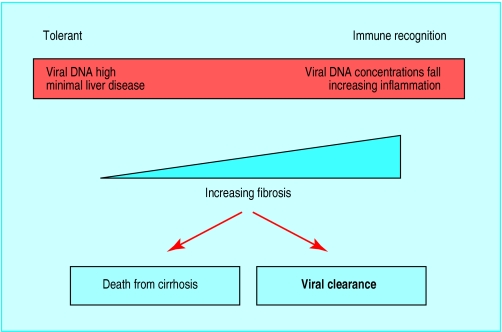

Chronic hepatitis B virus infection can be thought of as occurring in phases dependent on the degree of immune response to the virus. If a person is infected when the immune response is “immature,” there is little or no response to the hepatitis B virus. The concentrations of hepatitis B viral DNA in serum are very high, the hepatocytes contain abundant viral particles (surface antigen and core antigen) but little or no ongoing hepatocyte death is seen on liver biopsy because of the defective immune response. Over some years the degree of immune recognition usually increases. At this stage the concentration of viral DNA tends to fall and liver biopsy shows increasing inflammation in the liver. Two outcomes are then possible, either the immune response is adequate and the virus is inactivated and removed from the system or the attempt at removal results in extensive fibrosis, distortion of the normal liver architecture, and eventually death from the complications of cirrhosis.

Assessment of chronic hepatitis B infection

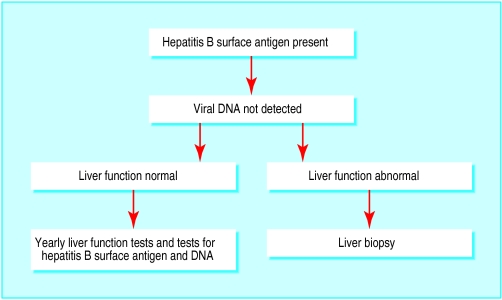

Patients positive for hepatitis B surface antigen with no evidence of viral replication, normal liver enzyme activity, and normal appearance on liver ultrasonography require no further investigation. Such patients have a low risk of developing symptomatic liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma. Reactivation of B virus replication can occur, and patients should therefore have yearly serological and liver enzyme tests.

Patients with abnormal liver biochemistry, even without detectable hepatitis B viral DNA or an abnormal liver texture on ultrasonography, should have liver biopsy, as 5% of patients with only surface antigen carriage at presentation will have cirrhosis. Detection of cirrhosis is important as patients are at risk of complications, including variceal bleeding and hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients with repeatedly normal alanine transaminase activity and high concentrations of viral DNA are extremely unlikely to have developed advanced liver disease, and biopsy is not always required at this stage.

Treatment

Interferon alfa was first shown to be effective for some patients with hepatitis B infection in the 1980s, and it remains the mainstay of treatment. The optimal dose and duration of interferon for hepatitis B is somewhat contentious, but most clinicians use 8-10 million units three times a week for four to six months. Overall, the probability of response (that is, stopping viral replication) to interferon therapy is around 40%. Few patients lose all markers of infection with hepatitis B, and surface antigen usually remains in the serum. Successful treatment with interferon produces a sustained improvement in liver histology and reduces the risk of developing end stage liver disease. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma is also probably reduced but is not abolished in those who remain positive for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Factors indicating likelihood of response to interferon in chronic hepatitis B infection

| High probability | Low probablility | |

| Age (years) | <50 | >50 |

| Sex | Female | Male |

| Viral DNA | Low | High |

| Activity of liver inflammation | High | Low |

| Country of origin | Western world | Asia or Africa |

| Coinfection with HIV | Absent | Present |

Side effects of treatment with interferon alpha

| Symptoms | Frequency (%) |

| Fever or flu-like illness | 80 |

| Depression | 25 |

| Fatigue | 50 |

| Haematological abnormalities | 10 |

| No side effects | 15 |

In general, about 15% of patients receiving interferon have no side effects, 15% cannot tolerate treatment, and the remaining 70% experience side effects but are able to continue treatment. Depression can be a serious problem, and both suicide and admissions with acute psychosis are well described. Viral clearance occurs through induction of immune mediated killing of infected hepatocytes. Transient hepatitis can therefore occasionally cause severe decompensation requiring liver transplantation.

Lamivudine is a nucleoside analogue that is a potent inhibitor of hepatitis B viral DNA replication. It has a good safety profile and has been widely tested in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection, mainly in the Far East. In long term trials almost all treated patients showed prompt and sustained inhibition of viral DNA replication, with about 17% becoming e antigen negative when treatment was continued for 12 months. There was an associated improvement of inflammation and a reduction in progression of fibrosis on liver biopsy. Side effects are generally mild. Combination therapy with interferon and lamivudine has not been found to have additional benefit.

Hepatitis C

Chronic hepatitis C virus infection has a long course, and most patients are diagnosed in a presymptomatic stage. In the United Kingdom, most patients are now discovered because of an identifiable risk factor (intravenous drug use, family history, or blood transfusion) or because of abnormal liver biochemistry. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection is based on enzyme linked immonosorbent assays (ELISA) using recombinant viral antigens and patients' serum. These have high sensitivity and specificity. The diagnosis is confirmed by radioimmunoblot and direct detection of viral RNA in peripheral blood by polymerase chain reaction. Viral RNA is regarded as the best test to determine infectivity and assess response to treatment.

Investigations required in patients positive for antibodies to hepatitis C virus

| Assessing hepatitis C virus | Excluding other liver diseases |

| • Polymerase chain reaction | • Ferritin |

| for viral RNA | • Autoantibodies/ immunoglobulins |

| • Viral load | • Hepatitis B serology |

| • Genotype | • Liver ultrasonography |

Natural course of hepatitis C infection

In order to assess the need for treatment it is important to have a clear understanding of the natural course of hepatitis C infection and factors that may predispose to more severe outcome. Our knowledge is limited because of the relatively recent discovery of the virus. It is clear, however, that hepatitis C is usually slowly progressive, with an average time from infection to development of cirrhosis of around 30 years, albeit with a high level of variability. The main factors associated with increased risk of progressive liver disease are age >40 at infection, high alcohol consumption, and male sex.

Viraemic patients with abnormal alanine transaminase activity need a liver biopsy to assess the stage of disease (amount of fibrosis) and degree of necroinflammatory change (Knodell score). Management is usually based on the degree of liver damage, with patients with more severe disease being offered treatment. Patients with mild changes are usually followed up without treatment as their prognosis is good and future treatment is likely to be more effective than present regimens.

Treatment of hepatitis C

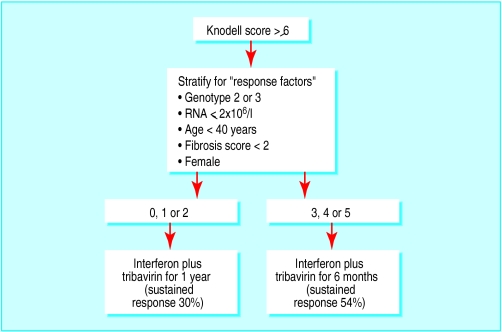

Interferon alfa (3 million units three times a week) in combination with tribavirin (1000 mg a day for patients under 75 kg and 1200 mg for patients ⩾75 kg) has recently been shown to be more effective than interferon alone. A large study in Europe showed no advantage to continuing treatment beyond six months in patients who had a good chance of response, whereas those with a poorer outlook needed longer treatment (12 months) to maximise the chance of clearing their infection. About 30% of patients will obtain a “cure” (sustained response). The main determinant of response is viral genotype, with genotypes 1 and 4 having poor response rates.

Further reading

Szmuness W. Hepatocellular carcinoma and the hepatitis B virus: evidence for a causal association. Prog Med Virol 1978;24:40-8.

Stevens CE, Beasley RP, Tsui V, Lee WC. Vertical transmission of hepatitis B antigen in Taiwan. N Engl J Med 1975;292:771-4.

Knodell RG, Ishak G, Black C, Chen TS, Craig R, Kaplowitz N, et al. Formulation and application of numerical scoring system for activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology 1981;1:431-5.

Summary points

Viral hepatitis is relatively common in United Kingdom (mainly hepatitis C)

Presentation is usually with abnormal alanine transaminase activity

Disease progression in hepatitis C is usually slow (median time to development of cirrhosis around 30 years)

Liver biopsy is essential in managing chronic viral hepatitis

New treatments for hepatitis C (interferon and tribavirin) and hepatitis B (lamivudine) have improved the chances of eliminating these pathogens from chronically infected patients

Combination therapy has the same side effects as interferon monotherapy with the additional risk of haemolytic anaemia. Patients developing anaemia should have their dose of tribavirin reduced. All patients should have a full blood count and liver function tests weekly for the first four weeks of treatment and monthly thereafter if haemoglobin concentration and white cell count are stable. Many new treatments are currently entering clinical trials, including long acting interferons and alternative antiviral drugs.

Figure.

Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among 1500 patients in Trent region,1998. Note: professional tattooing does not carry a risk

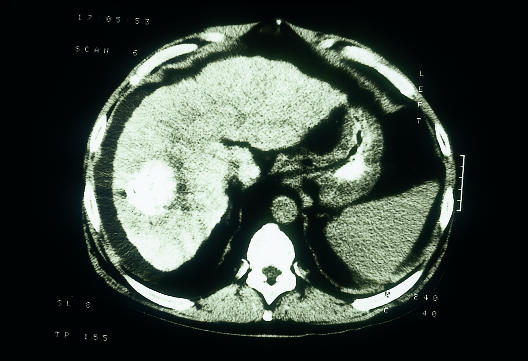

Figure.

Computed tomogram showing hepatocellular carcinoma, a common complication of cirrhosis

Figure.

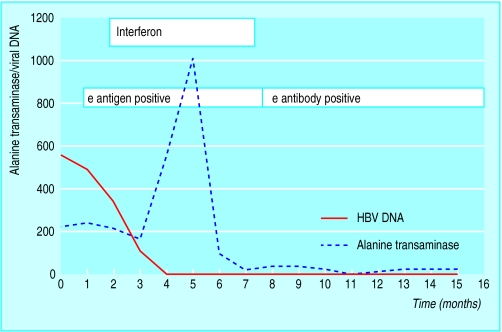

Phases of infection with hepatitis B virus

Figure.

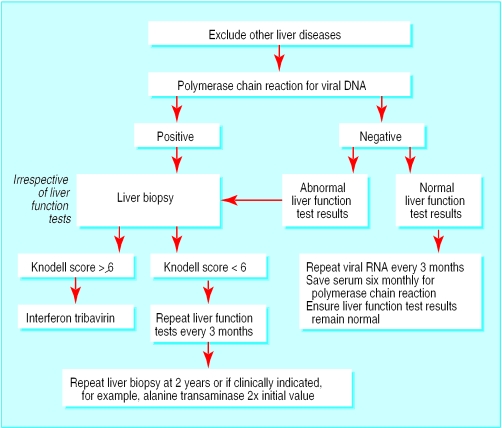

Investigation of patients positive for hepatitis B surface antigen without viral replication

Figure.

Timing of interferon treatment in the management of hepatitis B

Figure.

Management of chronic hepatitis C virus infection

Figure.

Combination therapy for hepatitis C

Footnotes

S D Ryder is consultant hepatologist, Queen's Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2UH

The ABC of diseases of liver, pancreas, and biliary system is edited by I J Beckingham, consultant hepatobiliary and laparoscopic surgeon, department of surgery, Queen's Medical Centre, Nottingham (Ian.Beckingham@nottingham.ac.uk). The series will be published as a book later this year.