INTRODUCTION

Knowledge of the locations and drainage patterns of the lymph nodes of the thoracic cavity is essential for the interpretation of thoracic radiographs and the development of differential diagnoses for radiographic abnormalities. The thoracic lymph nodes that may be visible on radiographs when enlarged include the sternal, mediastinal, and tracheobronchial lymph nodes. Proper radiographic identification of these structures can reduce the likelihood of misinterpreting enlarged lymph nodes and aid in the diagnostic process. In broad terms, lymphadenomegaly in adult dogs often results from neoplastic or inflammatory conditions, whereas antigenic stimulation and immune system development are additional considerations for young animals.

STERNAL LYMPH NODES

The sternal lymph nodes are located immediately dorsal to the 2nd or 3rd sternebrae in the ventral aspect of the cranial mediastinum (https://openpress.usask.ca/k9lymphaticsystem/chapter/figure-18-right-side-of-the-thoracic-cavity-of-the-dog/) (1,2). The sternal lymph nodes receive afferent lymph vessels from the cranial abdominal wall, diaphragm, ribs, sternum, mediastinum, pleura and peritoneum, thymus, and 1st and 2nd mammary glands and drain into the cranial mediastinal lymph nodes (1–3). Dogs typically have a single, oval-shaped sternal lymph node on each side of the thorax, though rarely, both are absent or located on the same side (2). The size of the normal sternal lymph nodes varies between 3 and 20 mm in length (2).

When enlarged, sternal lymph nodes are more easily visualized in the lateral views (Figure 1) (1,4). Only with moderate-to-marked enlargement would they become visible on the orthogonal view. On occasion, normal-sized sternal lymph nodes are visible in large-breed dogs, most often in the right lateral projection (5). When detected, they appear as a soft-tissue opaque, often crescent-shaped structure dorsal to the 2nd and 3rd sternebrae (4). There tends to be a broad base of contact between the ventral aspect of the enlarged lymph node and the sternum (1). Because the ventral aspect of the cranial mediastinum is narrow, there are no normal thoracic structures to silhouette with the sternal lymph nodes, allowing even mild lymphadenopathy to be detected in most cases (1).

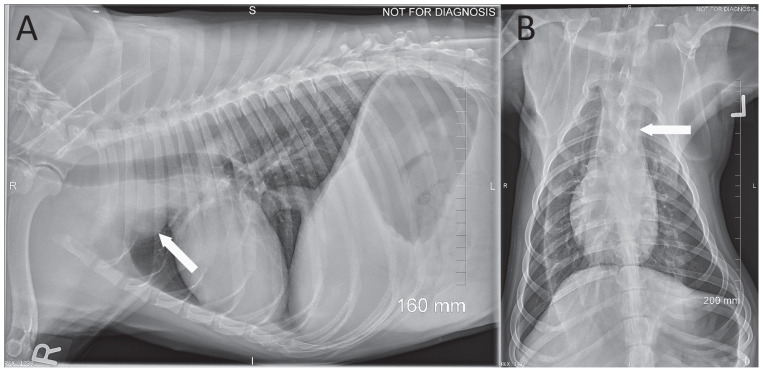

FIGURE 1.

Left lateral and ventrodorsal thoracic radiographs of a dog with sternal lymphadenopathy. On the lateral radiograph (A), a crescent-shaped increase in soft-tissue opacity (arrow) dorsal to the 2nd and 3rd sternal vertebrae is visible. On the ventrodorsal radiograph (B), a moderate, soft-tissue opaque widening of the cranial mediastinum (arrow) is visible.

The sternal lymph nodes may be enlarged in disease processes affecting the abdomen due to the afferent drainage of abdominal structures by these lymph nodes (1,2). The most common cause of enlarged sternal lymph nodes in dogs is neoplasia; in one study, 79% (56/71) of dogs with radiographically enlarged sternal lymph nodes were diagnosed with cancer (6). The most common type of cancer involving the sternal lymph nodes was multicentric lymphoma, followed by splenic hemangiosarcoma (6). Although the sternal lymph node does not receive efferent lymphatics from the spleen (2), it does drain the peritoneal cavity, and the lymphadenopathy in dogs with splenic hemangiosarcoma is likely due to drainage of blood containing cancer cells from tumor hemorrhage. Other tumor types, including sarcomas, carcinomas, mast cell tumors, and melanoma, are less-common causes of sternal lymphadenopathy (6). In 1 study, 14% (10/71) of dogs with sternal lymphadenopathy were diagnosed with nonneoplastic infectious and inflammatory diseases including pulmonary granulomatosis, pulmonary blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, discospondylitis, bacterial pericarditis, peritonitis, and hepatitis (6). Hematologic conditions such as disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and immune-mediated thrombocytopenia can also result in enlarged sternal lymph nodes, though this is an uncommon etiology (6).

MEDIASTINAL LYMPH NODES

The mediastinal lymph center in the dog most commonly includes only the cranial mediastinal lymph nodes, which are located between the 1st rib and the heart, ventral to the trachea (https://openpress.usask.ca/k9lymphaticsystem/chapter/figure-17-lymph-vessels-of-the-mediastinum-pericardium-diaphragm-aorta-and-esophagus-in-the-dog/) (1,2). These lymph nodes drain the musculoskeletal structures of the neck and thorax, as well as the trachea, esophagus, thyroid gland, thymus, costal pleura, heart, and aorta (1,2). Lymph vessels from the sternal lymph nodes drain to the cranial mediastinal lymph nodes, so disease in all regions drained by the sternal lymph nodes may also affect the cranial mediastinal lymph nodes (2). The cranial mediastinal lymph nodes also drain the tracheobronchial lymph nodes (described below), and intercostal, cervical, and pulmonary lymph nodes (2).

Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes can be difficult to visualize on thoracic radiographs due to other structures in this region that cause the mid-aspect of the cranial mediastinum to be wider than the cranioventral or caudal mediastinum. On radiographs, mediastinal lymphadenopathy may elevate the trachea dorsally (7), though this can be mild and difficult to detect. Generally, when the cranial mediastinal lymph nodes are enlarged, an ill-defined increase in soft-tissue opacity may be noted ventral to the trachea on the lateral views (Figure 2). Detection may be aided by the dorsoventral or ventrodorsal projections, where widening of the mediastinum would be visible. However, since fat in the mediastinum is a frequent cause of cranial mediastinal widening, it is important not to over-read this finding (7). Furthermore, the thymus in young dogs causes increased soft-tissue opacity within the cranial mediastinum (7). Ultimately, computed tomography may be required to confirm mediastinal lymph node enlargement (8).

FIGURE 2.

Right lateral and ventrodorsal thoracic radiographs of a dog with cranial mediastinal lymphadenopathy. On the lateral view (A), a moderate, structured increase in soft-tissue opacity in the cranial thorax (arrow) is visible just ventral to the intrathoracic trachea and is causing a mild elevation of the trachea. On the ventrodorsal radiograph (B), concurrent, mild widening of the cranial mediastinum (arrow) is seen. Cranial mediastinal lymphadenopathy was confirmed in this dog on a computed tomographic scan.

Cranial mediastinal lymphadenopathy is most frequently associated with neoplasia and mycotic infections (1). In 1 study, 100% (8/8) of dogs with lymphoma, 26% (9/34) of dogs with primary lung tumors, and 10% (9/90) of dogs with metastatic tumors presented with radiographically apparent mediastinal lymphadenopathy (9). Mycotic diseases including coccidiomycosis, blastomycosis, and histoplasmosis may also cause cranial mediastinal lymph node enlargement; 8% (2/24) of dogs with coccidiomycosis (1,7,10) demonstrated this finding. Interestingly, radiographically visible lymphadenopathy is typically not observed with bacterial pneumonia (tuberculosis, nocardiosis, actinomycosis), pyothorax, and rib tumors, even though the mediastinal lymph nodes receive drainage from the affected regions (7).

TRACHEOBRONCHIAL LYMPH NODES

The tracheobronchial lymph nodes typically include 3 lymph nodes located at the bifurcation of the trachea: a left and a right lymph node located on each side of the bifurcation and a middle lymph node located on the caudal aspect of the bifurcation (https://openpress.usask.ca/k9lymphaticsystem/chapter/figure-20-lymph-vessels-of-the-lungs-and-tracheobronchial-lymph-nodes-of-the-dog/) (2). The lungs, bronchi, thoracic portion of the esophagus, caudal portion of the trachea, mediastinum, diaphragm, heart, and aorta all drain to these lymph nodes (2). The tracheobronchial lymph nodes may be referred to as hilar or perihilar lymph nodes because they are located where the pulmonary and bronchial vessels enter the medial surface of the lung (the hilus) (11). On radiographs, the perihilar region broadly refers to the structures overlying the base of the heart. Lateral radiographs are more useful for detecting enlargement of these lymph nodes, as the anatomical complexity and superimposition of the cardiac silhouette may obscure the lymph nodes on ventrodorsal and dorsoventral views (12). In the lateral view, tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy frequently presents as a poorly defined increase in soft-tissue opacity in the perihilar region, particularly visible dorsocaudal to the tracheal bifurcation, causing displacement of the terminal trachea and caudal lobar bronchi ventrally (Figure 3) (1). On the ventrodorsal and dorsoventral views, lymph node enlargement can cause a lateral divergence of the caudal lobar bronchi, which can be difficult to differentiate from left atrial enlargement (1). However, these 2 processes can be distinguished, as left atrial enlargement will elevate the trachea and caudal lobar bronchus on lateral views, whereas tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy will cause ventral deviation (1).

FIGURE 3.

Left lateral and ventrodorsal thoracic radiographs of a dog with tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy. On the lateral radiograph (A), a poorly defined increase in soft-tissue opacity is visible in the perihilar region (arrows). The cranial arrow indicates the region of the left and right tracheobronchial lymph nodes; the caudal arrow indicates the region of the middle tracheobronchial lymph node. Although the tracheobronchial lymph nodes are not clearly defined due to the superimposition of the cardiac silhouette on the ventrodorsal view (B), the enlargement of the middle tracheobronchial lymph nodes has caused a widening of the space between the caudal lobar bronchi and a poorly defined increase in soft-tissue opacity in this region (arrows).

The most common cause of tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy is neoplasia; 84% (92/110) of dogs with radiographically evident tracheobronchial lymphadenomegaly were diagnosed with cancer (13). Again, the most common cancer was multicentric lymphoma, affecting 60% (66/92) of the dogs diagnosed with neoplasia. Histiocytic sarcoma and carcinoma were the next-most diagnosed cancer types (13). Among dogs with nonneoplastic causes of lymphadenomegaly, Coccidioides and Aspergillus infections were reported to be the most common diagnoses (13). Canine eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy is another differential diagnosis to consider, with 9% (3/35) of affected dogs presenting with hilar lymphadenopathy (14).

In conclusion, radiographic identification of enlarged thoracic lymph nodes and knowledge of their drainage patterns are of considerable diagnostic value for veterinarians with respect to guiding the differential diagnosis list and selecting subsequent testing for a given animal with thoracic lymphadenomegaly.

Footnotes

Copyright is held by the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. Individuals interested in obtaining reproductions of this article or permission to use this material elsewhere should contact Permissions.

Questions

-

Which of the following thoracic cavity lymph nodes may be visible on radiographs even when it is normally sized?

Sternal

Cranial mediastinal

Tracheobronchial

None of the above

Answer: A

-

Which of the following statements is incorrect?

The cranial mediastinal lymph nodes drain lymph from both the sternal and the tracheobronchial lymph nodes.

The sternal lymph node may be enlarged due to a disease process within the peritoneal cavity.

The most common cause of enlargement of the sternal, cranial mediastinal, and tracheobronchial lymph nodes in an adult dog is neoplasia.

Widening of the cranial mediastinum on radiographs is pathognomic for cranial mediastinal lymph node enlargement.

Answer: D

REFERENCES

- 1.Thrall DE. Canine and feline mediastinum. In: Thrall, editor. Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: WB Saunders; 2018. pp. 649–669. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum H. In: The Lymphatic System of the Dog. Bellamy K, Mayer M, Bettin Leonie, editors. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: University of Saskatchewan Pressbooks; 1918 and 2021. [Last accessed May 13, 2024]. Available from: https://openpress.usask.ca/k9lymphaticsystem/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patsikas MN, Dessiris A. The lymph drainage of the mammary glands in the bitch: A lymphographic study. Part I: The 1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th mammary glands. Anat Histol Embryol. 1996;25:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1996.tb00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordella A, Saunders J, Stock E. Sternal lymphadenopathy in dogs with malignancy in different localizations: A CT retrospective study of 60 cases. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:1019196. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.1019196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirberger RM, Avner A. The effect of positioning on the appearance of selected cranial thoracic structures in the dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2006;47:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2005.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith K, O’Brien R. Radiographic characterization of enlarged sternal lymph nodes in 71 dogs and 13 cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2012;48:176–181. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-5750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suter PF, Lord PF. Thoracic Radiology: A Text Atlas of Thoracic Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 1st ed. Wettswil, Switzerland: PF Suter; 1984. pp. 247–283. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruby J, Secrest S, Sharma A. Radiographic differentiation of mediastinal versus pulmonary masses in dogs and cats can be challenging. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2020;61:385–393. doi: 10.1111/vru.12859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suter PF, Carrig CB, OBrien TR, Koller D. Radiographic recognition of primary and metastatic pulmonary neoplasms of dogs and cats. J Am Vet Radiol Soc. 1974;15:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson LR, Herrgesell EJ, Davidson AP, Pappagianis D. Clinical, clinicopathologic, and radiographic findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis: 24 cases (1995–2000) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222:461–466. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.222.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasquini C, Spurgeon T, Pasquini S. Anatomy of Domestic Animals: Systemic and Regional Approach. 5th ed. Pilot Point, Texas: Sudz Publishing; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackwood L, Sullivan M, Lawson H. Radiographic abnormalities in canine multicentric lymphoma: A review of 84 cases. J Small Anim Pract. 1997;38:62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1997.tb02989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones BG, Pollard RE. Relationship between radiographic evidence of tracheobronchial lymph node enlargement and definitive or presumptive diagnosis. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2012;53:486–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2011.01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson LR, Johnson EG, Hulsebosch SE, Dear JD, Vernau W. Eosinophilic bronchitis, eosinophilic granuloma, and eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy in 75 dogs (2006–2016) J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33:2217–2226. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]