Abstract

An 8-year-old castrated male Maltese dog was presented with a urinary bladder mass, urolithiasis, and hematuria. A solitary, pedunculated, intraluminal mass on the caudodorsal wall was identified with extensive irregular bladder wall thickening, and the mass was surgically removed. Postoperative histopathology demonstrated a submucosal lesion comprising spindle cells with marked inflammatory cell infiltration, without malignant changes. Immunohistochemical staining revealed vimentin and desmin positivity in the mass. An inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) was definitively diagnosed. No recurrence was observed during a 43-month follow-up period. Although IMTs are rare in dogs, they should be considered a differential diagnosis for mass-like urinary bladder lesions accompanying a chronic inflammatory disease process.

Key clinical message:

Canine IMT should be included in the differential diagnoses of bladder masses, especially when dogs exhibit chronic irritation and inflammation.

RÉSUMÉ

Tumeur myofibroblastique inflammatoire de la vessie chez un chien

Un chien maltais mâle castré de 8 ans a été présenté avec une masse à la vessie, une lithiase urinaire et une hématurie. Une masse intraluminale pédonculée solitaire sur la paroi caudodorsale a été identifiée avec un épaississement important et irrégulier de la paroi vésicale, et la masse a été retirée chirurgicalement. L’histopathologie postopératoire a mis en évidence une lésion à la sous-muqueuse comprenant des cellules fusiformes avec une infiltration cellulaire inflammatoire marquée, sans modification maligne. La coloration immunohistochimique a révélé une positivité à la vimentine et à la desmine dans la masse. Une tumeur myofibroblastique inflammatoire (IMT) a été définitivement diagnostiquée. Aucune récidive n’a été observée au cours d’une période de suivi de 43 mois. Bien que les IMT soient rares chez le chien, ils doivent être considérés comme un diagnostic différentiel des lésions de la vessie de type masse accompagnant un processus de maladie inflammatoire chronique.

Message clinique clé:

L’IMT canine doit être incluse dans les diagnostics différentiels des masses vésicales, en particulier lorsque les chiens présentent une irritation et une inflammation chroniques.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Ninety percent of canine urinary bladder neoplasms are of epithelial origin, with the majority being aggressive and invasive urothelial carcinomas (UCs) (1). Differentiating non-UC neoplasms or nonneoplastic lesions from UCs is crucial as treatment approaches and consequent prognoses differ substantially (2). These conditions can present with similar, nonspecific clinical signs, including hematuria, oliguria, pollakiuria, stranguria, or urinary obstruction (2). Therefore, a definitive diagnosis requires histopathology of the mass.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs) were first described as a reparative post-inflammatory condition in human lungs (3). These tumors occurred commonly in children and young adults, with a reported incidence rate of 0.04 to 0.7% (4,5). The etiology is not fully understood; however, previous surgery, trauma, and chronic infectious or immune-mediated processes have been associated with their development (6,7). Despite their rarity and the potential for misdiagnosis, there are documented cases and retrospective studies on bladder IMTs in humans (8,9).

This report describes a urinary bladder mass in a dog that was surgically removed and histopathologically confirmed as an IMT, and provides detailed diagnostic and clinical courses, including long-term follow-up.

CASE DESCRIPTION

An 8-year-old castrated male Maltese dog weighing 7.2 kg was referred for surgical treatment for a urinary bladder mass and urinary stones. The dog was presented with symptoms of pollakiuria and hematuria. Two weeks before the referral, oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (12.5 mg/kg q12h) had been prescribed for 7 d, but there was no improvement in clinical signs. The dog had undergone cystotomy for removal of calcium oxalate urolithiasis 3 y earlier. Afterward, the dog was fed a prescription diet (Hill’s c/d Multicare) but experienced a recurrence of bladder stones 4 mo post-surgery and suffered from intermittent chronic cystitis. In addition, 2 y earlier, the dog had been diagnosed with immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, which was treated, and related medication had since been discontinued.

At time of presentation, the dog was alert and in good condition. The CBC revealed mild leukocytosis [21.0 × 109/L, reference range (RR): 6 to 17 × 109/L] and thrombocytopenia (131 × 109/L, RR: 200 to 500 109/L). C-reactive protein level was within the reference interval (5 mg/L, RR: 0 to 10 mg/L). No remarkable serum chemistry profiles were observed, except for elevated alkaline phosphatase (298 U/L, RR: 23 to 212 U/L). Coagulation panels, including prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and d-dimer, were within the normal ranges. Plain thoracic/abdominal radiography revealed uroliths in the bladder and proximal urethra; the latter was moved to the bladder through retro-urohydropropulsion. On abdominal ultrasonography, a pedunculated bladder mass (2.8 × 1.6 cm) with a hypoechogenic center and hyperechogenic periphery was present near the trigone (Figure 1 A). The neck of the mass was 7 mm wide and 1 cm from the left ureteral opening. There was no invasion of the muscular layer of the bladder, and no lymphadenopathy or extravesical involvement was observed. The cranial region of the bladder wall was irregularly thickened (up to 6 mm). A double-contrast cystogram revealed an irregular, ovoid mass connected to the dorsocaudal bladder wall, with a short stalk and an irregular line of the bladder’s cranioventral lumen (Figure 1 B).

FIGURE 1.

An ultrasonogram (A) and a double-contrast cystogram (B) of a canine inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. In (B), the arrowheads indicate bladder stones; the arrow indicates neck attachment of the pedunculated mass.

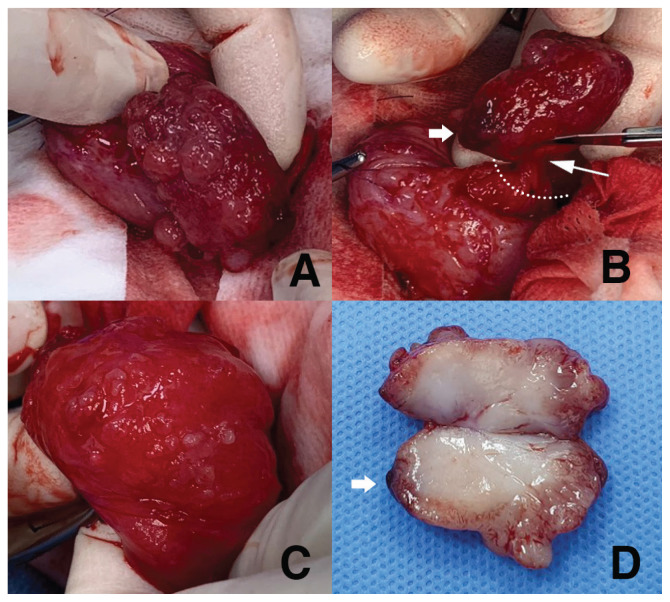

Under general anesthesia, 3 cystoliths were removed via cystotomy. The mass lesion, which was mildly firm but had a soft and movable mucosal attachment, was exteriorized through the incision and resected, including a 5-millimeter-wide area of normal mucosa around the stalk (Figure 2 A, B). When the cranioventral part of the bladder was turned inside out, the mucosal surface was irregular, with multiple projections (Figure 2 C). Therefore, an incisional full-thickness biopsy was completed. The dog was hospitalized, given IV fluids, ampicillin (20 mg/kg, q12h), and butorphanol (0.1 mg/kg, q12h). The dog recovered without complications, with a good appetite and normal activity. Bacterial culture and stone analysis were not authorized by the owner. Upon gross inspection, the mass had several polypoid protrusions on the irregular mucosal surface, with a dark, bruised region suspected to be a bleeding site. The mass measured,3.5 cm along the longest axis. A cut surface revealed a pale pink, soft-to-fragile edge and a relatively firm, dense, creamy white center (Figure 2 D).

FIGURE 2.

Surgical images of a canine inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in the urinary bladder. A — Gross appearance of the intravesical mass. B — Excision of the mass including 5-millimeter mucosal margin. C — Intraluminal mucosal surface of the thickened cranioventral part of the bladder, showing multiple projections. D — Cross-section of the excised mass.

The dotted line (B) indicates the excision line; the thin arrow (B) points to the neck attachment of the pedunculated mass; the thick arrows (B, D) highlight the bruised point assumed to be responsible for hematuria.

On histopathologic examination (Figure 3 A, B), the small, nodular projections on the outer surface of the mass comprised well-differentiated urothelium overlying a core of loose, edematous, fibrovascular connective tissue cells. Occasionally, epithelial cells invaginated into the underlying superficial submucosa with Brunn’s nest formation. Within the deep submucosa and superficial detrusor muscle, there was a fairly discrete and moderately cellular mass comprising plump, spindloid-to-fusiform cells interpreted to be myofibroblastic or fibroblastic phenotypes. They were arranged in ill-defined streams, bundles, and fascicles, intermingled with marked infiltrates of small, mature lymphocytes, plasma cells, and lesser numbers of histiocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils. The mass was supported by prominent small-caliber blood vessels. Atypical spindle cells were strongly immunoreactive for vimentin and desmin (Figure 3 C, D) but immunonegative for smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Figure 3 E). Few spindle cells displayed very faint equivocal immunoreactivity to calponin (Figure 3 F). A definitive diagnosis of IMT was made. The full-thickness transmural biopsy sample revealed chronic ulcerative cystitis characterized by mucosal ulceration and submucosal granulation tissue formation.

FIGURE 3.

Microscopic images of a canine inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in the urinary bladder. A mass in the submucosa contains an atypical spindle cell population and mixed cellular inflammation with hyperplasia of the overlying mucosa and Brunn’s nests (A, B; H&E staining). The immunoreactivity of the atypical spindle cell population is positive to vimentin (C) and desmin (D), but negative to smooth muscle actin (E) and faintly equivocal to calponin (F). Scale bars: A = 500 μm; B, C, D, E, F = 50 μm.

The dog was discharged on postoperative Day 3 without any urination issues. Subsequently, he was examined regularly at the referring hospital. There was complete remission of clinical signs after surgery, and neither recurrence of the mass nor urolithiasis has been identified to date. The dog is still doing well 43 mo post-surgery.

DISCUSSION

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors are rare neoplasms with intermediate biologic potential, belonging to the group of inflammatory spindle cell lesions (10). These masses feature a predominant cellular component of neoplastic, fibroblastic, and myofibroblastic cells with limited mitotic activity and no abnormal mitotic figures, accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate of varying proportions of plasma cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and occasionally, eosinophils or neutrophils (6,11–13). A myofibroblast is a cell phenotype that exhibits characteristics of both smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts that can produce collagen and is responsible for tissue repair; e.g., wound healing (14,15). Myofibroblasts secrete cytokines that serve as chemoattractants for inflammatory cells and may account for infiltration of inflammatory cells within the tumor mass (16,17). In the past, IMT was considered a subcategory of inflammatory pseudotumor, and the terms “IMT” and “inflammatory pseudotumor” were often used interchangeably (12). However, it is important to note that an inflammatory pseudotumor is a more inflammatory reactive or regenerative lesion that can often be treated conservatively (18). It represents a bland spindle cell proliferation with inflammatory infiltrates similar to IMT, but it does not exhibit recurrence or metastasis, distinguishing it as a separate disease from IMT (12,18). Conversely, some cases of IMT have demonstrated aggressive behavior and molecular expression of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangements (10,17). Therefore, IMT was classified as a distinctive neoplasm with characteristics of high recurrence rate but low metastatic potential in humans (12). Local recurrence rates of up to 25% and distant metastasis rates of up to 5% were reported (19).

Regarding urinary bladder masses in dogs, clinical symptoms and morphologic findings from diagnostic imaging are not enough to make a diagnosis. In the present case, preoperative differential diagnoses included polypoid cystitis and UC. The former is a benign epithelial proliferation induced by inflammation or a hyperplastic reaction to chronic irritation (20). It presents as polypoid or pedunculated masses with isoechogenicity, frequently in the cranioventral or craniodorsal bladder mucosa, but also occasionally has diffuse thickening of the wall (21). Urine culture had positive results in 60% of dogs with polypoid cystitis (20). Conversely, UC reveals broad-based masses (70%) that commonly involve the trigone (50%) and frequently invades the muscular layer, resulting in bladder wall layer disruption (22). In the current case, the pedunculated lesion had heterogeneous echogenicity on the caudodorsal wall without muscular invasion, which is not typical for either entity.

Microscopically, canine bladder IMTs featured mucosal inflammation, Brunn’s nests, and the presence of inflammatory cells within the masses, sharing a similar cellular composition with eosinophilic polypoid cystitis (1,6). However, eosinophilic polypoid cystitis is characterized by eosinophilic predominance and occasionally occurs without proliferation of connective tissue components, whereas IMTs exhibit a plasma cell- and lymphocyte-rich property (23). Furthermore, IMTs may be confused with spindle cell tumors, such as leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and sarcomatoid carcinoma, but can be differentiated by the absence of the corresponding findings of malignancy, cytologic atypia, infiltrative growth pattern, mitotic figures, myxoid degeneration, predominance of neutrophils, or extensive necrosis (23). Urothelial carcinoma is histologically characterized by large epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large and immature nuclei, and numerous mitoses, and by the presence of Melamed-Wolinska bodies, which are large cytoplasmic vacuoles (1,24). In addition, it often exhibits some amount of invasion that may extend throughout the entire histologic section. In challenging cases, immunohistochemistry for uroplakin III and potentially GATA-3 can be used to confirm the urothelial origin (2,25).

Although key histopathologic features may be present, a confirmative diagnosis typically requires immunophenotyping of atypical spindle cells. Various markers of myoid and stromal differentiation are used for immunohistochemistry; however, none are specific for diagnosing IMT (26). Commonly used markers for myofibroblast differentiation include vimentin, desmin, and SMA (27). Many IMTs express SMA either focally or diffusely in varying degrees, but,20 to 30% of human cases did not (8,27,28). As with the canine IMT case in this report, a systematic review by Chun J et al noted that 32 out of 114 human bladder IMTs stained negative for SMA (8). In previous reports of canine IMT, all spindle cells reacted strongly to vimentin, whereas percentages of SMA- and desmin-positive cells varied from 1 to 16% and from 0 to 36%, respectively (6,13). The diagnosis of IMT in this case was confirmed through a comprehensive analysis using hematoxylin and eosin staining as well as immunohistochemistry. The mass within the submucosa was composed of an atypical spindle cell population and mixed cellular inflammation, along with hyperplasia of the overlying mucosa. Immunophenotyping of the atypical cells revealed positive staining for vimentin and variable staining for myofibroblast and smooth muscle markers, faint equivocal staining for calponin, and positive staining for desmin. Staining patterns for these markers can vary in IMT. Rearrangement of the ALK locus on chromosome 2p23, detected in 50 to 65% of all human IMTs (8,10), can lead to aberrant expression and constitutive activation of the ALK tyrosine kinase, resulting in uncontrolled cell proliferation (29). These gene rearrangements have been reported in up to 65 to 75% of bladder IMTs. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive IMT was more prevalent in younger females than ALK-negative IMT, but no significant difference in prognosis was observed (8,9). An ALK rearrangement has not been reported in any neoplasia, including IMT, in dogs.

Canine IMTs have been infrequently reported with lacrimal, cardiac, spinal, nasal, and pancreatic involvement (7,13,30–32). In addition, 2 reports described IMTs in the urinary bladder, characterized by single or multinodular, intraluminal, polypoid, and firm masses with prominent hematuria and occasional abdominal pain (6,33). There was no reported history of surgery or trauma, and some dogs had cystitis and urolithiasis. In the present case, the dog had a history of cystotomy as well as recurrent urolithiasis, which was assumed to have contributed to chronic mechanical irritation of the bladder wall for > 3 y. This could have caused excessive inflammation and predisposed the animal to IMT development, although examinations to detect infectious agents were omitted. Pollakiuria and hematuria resolved after the surgical removal of the mass and urinary stones, and no further clinical or urinary problems were observed for up to 43 mo after surgery. Previous reports of dogs with bladder IMTs had favorable outcomes, with complete remission of clinical signs and no recurrence, regardless of the completeness of surgical resection (6,33). In humans, surgery is the most effective therapeutic approach for managing IMT with subsequently good prognosis (8,9). Alternative treatment options, such as radiation, chemotherapy, and corticosteroids, are available in cases of incomplete excision or recurrence (34). A Maltese dog with meningeal IMT was successfully managed through incomplete surgical resection and administration of prednisolone for 2.5 y (35). In another case, a local recurrence that occurred 2 mo after splenectomy for splenic IMT in a kitten effectively resolved with prednisone (36).

In conclusion, this report describes a dog with bladder IMT that was completely removed surgically and has not recurred for > 43 mo. Canine IMT is rare, but it should be included in the list of differential diagnoses for bladder masses, especially when dogs have chronic mechanical irritation associated with urolithiasis or chronic inflammation. Since a favorable prognosis can be expected after surgery, histopathology should always be conducted as part of the diagnostics. CVJ

Footnotes

Copyright is held by the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. Individuals interested in obtaining reproductions of this article or permission to use this material elsewhere should contact Permissions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meuten DJ, Meuten TLK. Tumors of the urinary system. In: Meuten DJ, editor. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Cary, North Carolina: Wiley Blackwell; 2017. pp. 632–688. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knapp DW, McMillan SK. Tumors of the urinary system. In: Withrow SJ, Vail DM, Page RL, editors. Withrow & MacEwen’s Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 5th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Saunders; 2013. pp. 572–582. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunn H. Two interesting benign lung tumors of contradictory histopathology. J Thorac Surg. 1939;9:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golbert ZV, Pletnev SD. On pulmonary “pseudotumours”. Neoplasma. 1967;14:189–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerfolio RJ, Allen MS, Nascimento AG, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:933–936. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Böhme B, Ngendahayo P, Hamaide A, Heimann M. Inflammatory pseudotumours of the urinary bladder in dogs resembling human myofibroblastic tumours: A report of eight cases and comparative pathology. Vet J. 2010;183:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swinbourne F, Kulendra E, Smith K, Leo C, Ter Haar G. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour in the nasal cavity of a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2014;55:121–124. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teoh JY, Chan NH, Cheung HY, Hou SS, Ng CF. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the urinary bladder: A systematic review. Urology. 2014;84:503–538. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C, Huang M, He H, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the urinary bladder: An 11-year retrospective study from a single center. Front Med. 2022;9:831952. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.831952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleason BC, Hornick JL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: Where are we now? J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:428–437. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.049387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakurai H, Hasegawa T, Watanabe Si, Suzuki K, Asamura H, Tsuchiya R. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:155–159. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00678-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siemion K, Reszec-Gielazyn J, Kisluk J, Roszkowiak L, Zak J, Korzynska A. What do we know about inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors? A systematic review. Adv Med Sci. 2022;67:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2022.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knight C, Fan E, Riis R, McDonough S. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in two dogs. Vet Pathol. 2009;46:273–276. doi: 10.1354/vp.46-2-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chitturi RT, Balasubramaniam AM, Parameswar RA, Kesavan G, Haris KM, Mohideen K. The role of myofibroblasts in wound healing, contraction and its clinical implications in cleft palate repair. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:75–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koga M, Kuramochi M, Karim MR, Izawa T, Kuwamura M, Yamate J. Immunohistochemical characterization of myofibroblasts appearing in isoproterenol-induced rat myocardial fibrosis. J Vet Med Sci. 2019;81:127–133. doi: 10.1292/jvms.18-0599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bagalad BS, Mohan Kumar KP, Puneeth HK. Myofibroblasts: Master of disguise. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:462–463. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_146_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagenstad CT, Kilpatrick SE, Pettenati MJ, Savage PD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with bone marrow involvement. A case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:865–867. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-865-IMTWBM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Höhne S, Milzsch M, Adams J, Kunze C, Finke R. Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT): A representative literature review occasioned by a rare IMT of the transverse colon in a 9-year-old child. Tumori. 2015;101:249–256. doi: 10.5301/tj.5000353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto H. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours WHO Classification of Tumours. 5th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency For Research on Cancer; 2020. pp. 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez I, Mattoon JS, Eaton KA, Chew DJ, DiBartola SP. Polypoid cystitis in 17 dogs (1978–2001) J Vet Intern Med. 2003;17:499–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2003.tb02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takiguchi M, Inaba M. Diagnostic ultrasound of polypoid cystitis in dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 2005;67:57–61. doi: 10.1292/jvms.67.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamlin AN, Chadwick LE, Fox-Alvarez SA, Hostnik ET. Ultrasound characteristics of feline urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma are similar to canine urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2019;60:552–559. doi: 10.1111/vru.12777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuller TW, Dangle P, Reese JN, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the bladder masquerading as eosinophilic cystitis: Case report and review of the literature. Urology. 2015;85:921–923. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webb KL, Stowe DM, DeVanna J, Neel J. Pathology in practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2015;247:1249–1251. doi: 10.2460/javma.247.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knapp DW, Ramos-Vara JA, Moore GE, Dhawan D, Bonney PL, Young KE. Urinary bladder cancer in dogs, a naturally occurring model for cancer biology and drug development. ILAR J. 2014;55:100–118. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilu018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu S, Yuan R, Jin Y, He C, Zheng X, Zhan Y. Clinicopathological features of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in the breast. Breast J. 2022;2022:1863123. doi: 10.1155/2022/1863123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Telugu RB, Prabhu AJ, Kalappurayil NB, Mathai J, Gnanamuthu BR, Manipadam MT. Clinicopathological study of 18 cases of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors with reference to ALK-1 expression: 5-year experience in a tertiary care center. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51:255–263. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2017.01.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle LA, Hornick JL. Immunohistochemistry of neoplasms of soft tissue and bone. In: David J, editor. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier; 2019. pp. 82–136. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai R, Ingham RJ. The pathobiology of the oncogenic tyrosine kinase NPM-ALK: A brief update. Ther Adv Hematol. 2013;4:119–131. doi: 10.1177/2040620712471553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tursi M, Garofalo L, Muscio M, et al. Verrucoid lesions of mitral valve in a dog with features of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2009;18:315–316. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuniya T, Shimoyama Y, Sano M, Watanabe N. Inflammatory pseudotumour arising in the epidural space of a dog. Vet Rec Case Rep. 2014;2:e000095. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romanucci M, Defourny SV, Massimini M, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreas in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2019;31:879–882. doi: 10.1177/1040638719879737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rocha NS, Tostes R, Ranzani JJT, Schmidt F. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the urinary bladder in dogs: Two cases. Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinaria e Zootecnia. 2002;54:450–453. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood SS, Narla S, Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics. 2003;23:719–729. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loderstedt S, Walmsley GL, Summers BA, Cappello R, Volk HA. Neurological, imaging and pathological features of a meningeal inflammatory pseudotumour in a Maltese terrier. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51:387–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferro S, Chiavegato D, Fiorentin P, Zappulli V, Di Palma S. A recurrent inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor-like lesion of the splenic capsule in a kitten: Clinical, microscopic and ultrastructural description. Vet Sci. 2021;8:275. doi: 10.3390/vetsci8110275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]