Abstract

Aims

Myocardial response to stress echocardiography may be elicited physiologically, through exercise, or pharmacologically, often with dobutamine. Both have advantages but also limitations due to reduced exercise capacity or side-effects to stressor agent/lack of closeness to true pathophysiology of ischaemic cascade. We have combined low-dose dobutamine and exercise, creating a ‘hybrid’ protocol to utilize the advantages of both techniques and limit the drawbacks. The aim of the study was to evaluate its safety and feasibility.

Methods and results

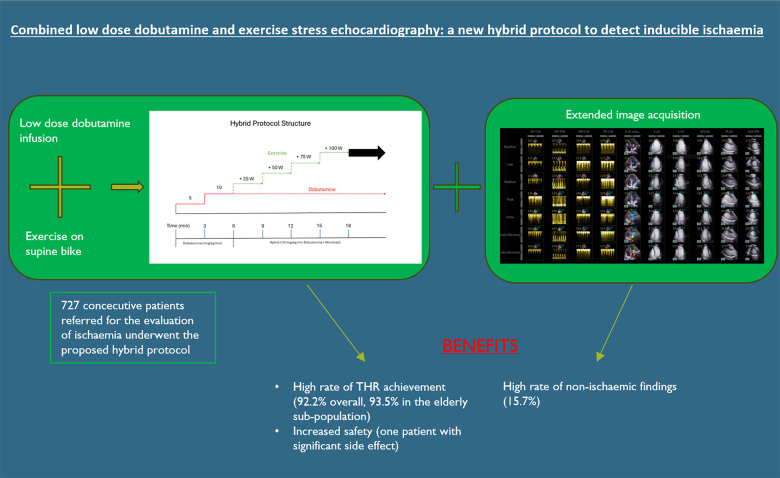

In the hybrid protocol, low-dose dobutamine infusion (up to 10 µg/kg/min) is enhanced by supine bicycle exercise at 3-min increments of workload of 25 W to achieve target heart rate (THR). We analysed safety and outcome data for all the patients who underwent this protocol from 2017 to 2022. Out of 835, 727 (87.1%) patients referred for evaluation of ischaemia underwent the hybrid protocol. The median age was 61 years old and 61% (442/727) were men. The median exercise time was 11 (9–13.5) min with a median maximum workload of 100 W (75–125). Out of 727, 670 (92.2%) achieved THR. Atropine was not used. Out of 727, 192 (26.4%) of studies were positive for ischaemia. Out of 122, 102 (83.6%) with positive stress who underwent invasive angiography had significant coronary disease. The incidence of complications was low: 1/727—severe arrhythmia, 5/727 (0.7%) developed a vasovagal episode, and 14/727 (1.9%) had a hypertensive response to exercise.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that this protocol is safe, feasible, and has a high success rate in achieving THR.

Keywords: stress echocardiography, hybrid protocol, coronary artery disease, non-invasive tests, dobutamine stress echocardiography, exercise stress echocardiography

Graphical Abstract

Graphical abstract.

Aims

Stress echocardiography (SE) is an established imaging modality for the detection of inducible cardiac ischaemia.1–3 Current practice is to elicit myocardial response to stress either pharmacologically or physiologically with exercise.4

Exercise is the preferred mechanism of stress because it induces the ischaemic cascade physiologically and offers the ancillary benefit of assessing an individual’s exercise capacity and symptomatic burden.5 However, it is limited by mobility and level of fitness: two in five patients are unable to achieve the required heart rate.4

Among those deemed incapable to exercise to required heart rate, dobutamine stress echocardiography (DSE) protocol is used to pharmacologically increase myocardial oxygen demand and induce regional ischaemia in flow-limiting coronary lesions. Recruitment of regional contractility is easy to appreciate even at the low infusion rates and images do not have interference from respiration. In contrast to exercise, it gives no assessment of exercise capacity and might not provoke daily symptoms. Moreover, at high dose, dobutamine causes vasovagal response and tachyarrhythmias, which are stressful for patients and disturb the efficient running of stress echo lists.6,7 Atropine which is used to counteract vasovagal episodes is often used as an adjunct to dobutamine to bolster the heart rate response. The use of atropine causes inconvenience for patients due to antimuscarinic effects and they are not allowed to drive home.8

We developed a hybrid stress echocardiography protocol (HPSE) combining low-dose dobutamine infusion (maximum 10 µg/kg/min) with supine bike exercise for assessment of myocardial ischaemia. The purpose was to maximize the proportion of individuals able to achieve a target heart rate (THR) through exercise while minimizing expected complications of higher dose dobutamine and avoid the use of atropine.

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the feasibility and safety of this protocol among the consecutive patients referred to our department for ischaemic assessment between 2017 and 2022 and to compare this with the data obtained from DSE studies performed in the department prior to 2017.

Methods

Study design

Among those deemed likely to achieve the THR, we used exercise-only stress echocardiography (ESE) protocol as a first choice. In all other patients the HPSE became the standard SE format. We reserved standard DSE for patients with severe mobility issues that are totally unable to pedal on a supine bike.

We received ethical approval for prospective and retrospective data collection following the initiation of the hybrid protocol as a quality control assessment from relevant oversight bodies at Harefield site of Guys and St Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust (Rec Reference 20/EM/0112).

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed using smart stress protocol on GE Vivid E95 machine. Post-processing analysis was performed offline on TomTec software (TTA 2.50).

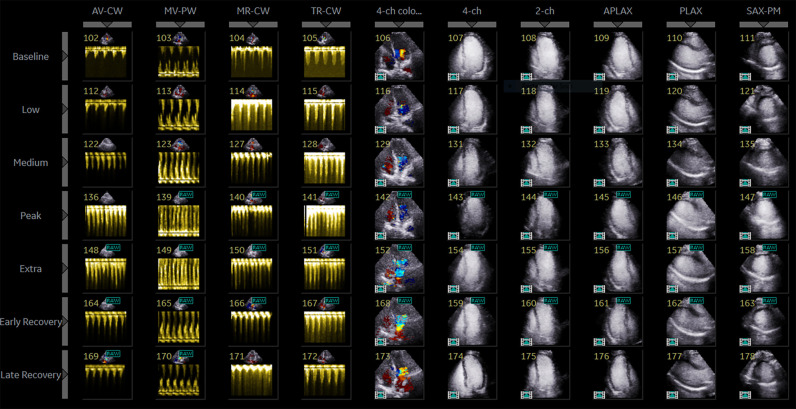

In our protocol, 10-echo views are acquired for each stage (Figure 1): four Doppler (Aortic Valve Continuous Wave—AV CW, Mitral Valve Pulse Wave—MV PW, Mitral Valve Continuous Wave—MV CW, Tricuspid Valve Continuous Wave—TR CW) and six colour and 2D left ventricular (LV) images including apical 4-chamber with and without colour Doppler (A4C), apical 2 chamber (A2C), apical 3 chamber (A3C), parasternal long-axis (PLAX), and mid-segment short-axis LV (mid SAX). Endocardial visualization is optimized with Sonovue™ contrast. We visualize five stages: Baseline, low-dose dobutamine, early exercise (HR∼100 BPM), peak exercise (THR), and recovery (with an option to add extra peak and early recovery in cases of abnormal exercise findings).

Figure 1.

Protocol screen.

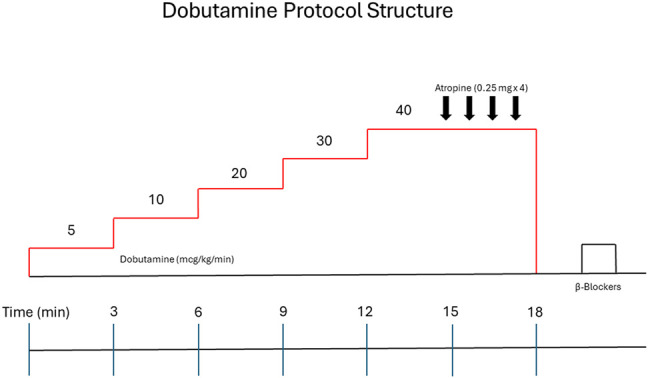

Dobutamine stress protocol

Dobutamine was infused according to standard guideline-directed fashion (Figure 2).4

Figure 2.

DSE protocol structure.

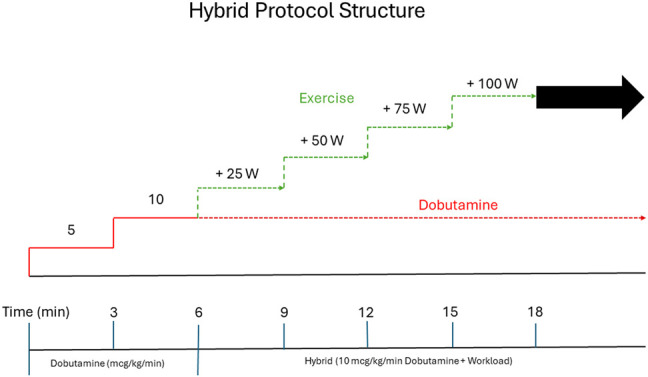

Hybrid stress protocol

The hybrid protocol combines the pharmacological effects of low-dose dobutamine with the physiological effect of supine bike exercise (Figure 3). While the patient is at rest, dobutamine is infused intravenously starting at 5 µg/kg/min, for 3 min. This is then titrated up to 10 µg/kg/min (the maximum dose) and is maintained until the recovery phase.

Figure 3.

HSE protocol structure.

During the initial low-dose dobutamine infusion (3 min of 5 µg/kg/min and 3 min of 10 µg/kg/min), the second set of images is acquired. After 6 min of dobutamine-only infusion, the THR is achieved by addition of supine bicycle exercise at 3-min increments of workload of 25 Watts (W) until test termination criteria are met. Exercise capacity is assessed as ability to perform on-protocol incremental exercise time, which excludes the dobutamine-only initial phase. Sublingual glycerine trinitrate and metoprolol are the protocol’s approved medication for the relief of symptoms of ischaemia.

Supine exercise

We use a supine exercise bike that can be tilted in the left lateral decubitus position (Figure 4). We find this substantially improves image acquisition during exercise compared with an inability to tilt the bike. Pedal resistance is manually adjusted in increments of 25 W every 3 min.

Figure 4.

Hybrid stress echocardiography laboratory.

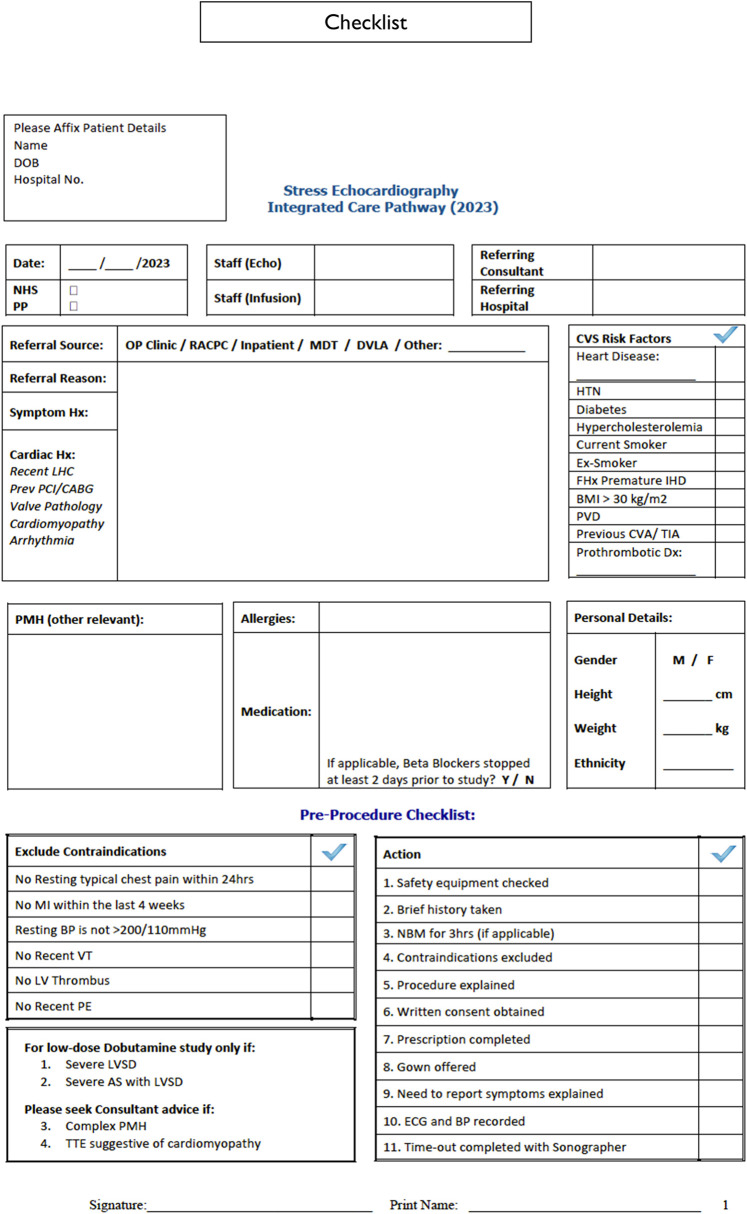

Safety, contraindications, and termination criteria

All procedures are preceded by a standardized checklist (Figure 5). Standard dobutamine and exercise echocardiography contraindications are used as exclusion criteria: unstable angina within last 24 h of scheduled test, MI in the last 4 weeks, poorly controlled hypertension, recent ventricular tachycardia (VT), persistent LV thrombus, and recent pulmonary embolism.4

Figure 5.

Pre-procedural notes.

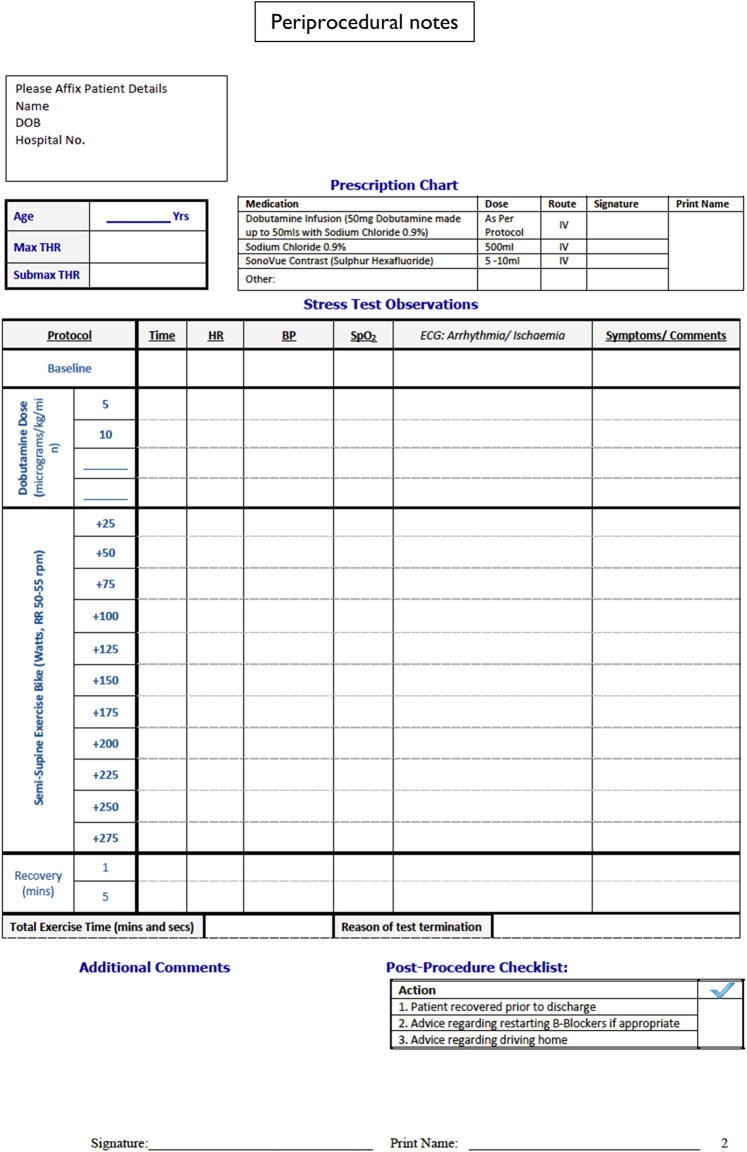

Standard termination criteria for dobutamine and exercise echocardiography were used.4 These are achieving THR, sustained systolic blood pressure >220 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >120 mmHg, sustained significant tachyarrhythmia, leg exhaustion, and irretractable symptoms. THR was calculated as 85% of maximum predicted heart rate (MHR) for age. In our safety monitoring we define significant arrhythmias as ventricular fibrillation, VT, or others, if they led to haemodynamic instability. Blood pressure was measured on the right arm every 3 min. The 12-Lead ECG was monitored throughout the test and paper prints were done for each stage. Detailed recording of all haemodynamic parameters and symptoms was made during the test using periprocedural notes (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Periprocedural notes.

Tests are considered positive for inducible regional dysfunction if more than one LV segments have an abnormal response at peak stress.

Statistics

All continuous variables were assessed for normality via Shapiro–Wilk testing. Parametric data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and non-parametric data presented as median (interquartile range). Categorial data are presented as percentages (n value). Descriptive statistics were analysed using SPSS Statistics v28.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Study population

Among all patients referred from September 2017 to January 2022, 88/835 (10.5%) underwent ESE, 20/835 (2.4%) DSE, and 727/835 (87.1%) HPSE. The completeness of studies of HPSE was compared with the data from 105 consecutive patients who underwent DSE in our department prior to 2017 (median age 63 year old, 70% males).

Baseline characteristics of study population are summarized in Table 1. The median age of the population was 61 year old, 187/727 (25.7%) were older than 70 years. Out of 727, 442 (61%) were males. There was a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors: 395/727 (54.3%) had a previous history of coronary artery disease (CAD), 370/727 (50.9%) hypertension, 142/727 (19.5%) diabetes, and 443/727 (60.9%) hypercholesterolaemia. Out of 727, 213 (29.3%) had a prior history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and 64/727 (9%) a previous history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). One-third of patients (240/727) were overweight (BMI > 30 kg/m2) and 10% (71/727) were current smokers.

Table 1.

Baseline population characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | Hybrid population (n = 727) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years) | 61 (52–70) |

| Age ≥ 80 years % (n) | 6.4 (46) |

| Age 70–80 years % (n) | 19.4 (141) |

| Male gender % (n) | 60.8 (442) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 (24.6–31.3) |

| Comorbidities | |

| CAD % (n) | 54.3 (395) |

| Other heart disease % (n) | 9.8 (71) |

| Hypertension % (n) | 50.9 (370) |

| Diabetes % (n) | 19.5 (142) |

| Hypercholesterolemia % (n) | 60.9 (443) |

| Smoking % (n) | 9.8 (71) |

| Ex-smoker % (n) | 31 (208) |

| Family history of premature IHD % (n) | 26.5 (193) |

| BMI > 30% (n) | 33 (240) |

| Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) % (n) | 2.6 (17) |

| Cerebral vascular accident (CVA) / transient ischaemic attack (TIA) % (n) | 3.4 (22) |

| Prothrombotic risk factors % (n) | 8.5 (62) |

| Previous coronary interventions | |

| PCI % (n) | 29.3 (213) |

| CABG % (n) | 8.9 (64) |

IHD, ischaemic heart disease.

The cardiology department, outpatient (OP) and rapid access chest pain (RACPC) clinics, was the main referring source (621/727, 85%). Out of 727, 85 (11.7%) did not have symptomatic status reflected in the referral form. The most common symptoms were chest pain in 445/727 (61.2%) patients and shortness of breath in 144/727 (19.8%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Referral characteristics

| Referring indication | |

|---|---|

| Referral source (n = 654) | |

| OP clinic % (n) | 66.1 (432) |

| RACPC % (n) | 28.9 (189) |

| Other % (n) | 5 (33) |

| Referral symptom (n = 642) | |

| Chest pain % (n) | 69.3 (445) |

| Shortness of breath % (n) | 22.5 (144) |

| Asymptomatic % (n) | 5.1 (33) |

| Other % (n) | 3.1 (20) |

Study results

Atropine was available but was not required in any study using HP. Isometric hand-grip exercises were encouraged in addition to supine bicycle exercise for the achievement of THR in 6/727 (0.8%) cases. Contrast agent was used in 692/727 (95.2%) of tests.

Haemodynamic parameters and echocardiographic characteristics at baseline and peak exercise are presented in Table 3. The use of the hybrid protocol led to high percentage of complete studies: 670/727 (92.2%) of all patients achieved the THR compared with 83/105 (79%) in DSE group (P < 0.0001). Amongst those who achieved THR, 181/670 (27%) in HPSE group were able to exercise at the MHR; whereas in DSE group, there were 6/83 (7%) patients (P < 0.0001). The median HP exercise time was 11 (9–13.5) minutes, and the median maximum workload was 100 W (75–125) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Baseline—peak exercise stress parameters

| Baseline | Peak Stress | |

|---|---|---|

| Haemodynamics | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 70 (63–79) | 152 (141–156) |

| Systolic blood pressure (BP) (mmHg) | 138.9 (±19.1) | 163 (±23.8) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 80 (72–87) | 82 (71–93) |

| Echo characteristics | ||

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 65 (62–69) | 79 (71–83) |

| LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) ml | 96 (79–117) | 78 (64–96) |

| LV end-systolic volume (LVESV) ml | 33 (26–43) | 16 (11–25) |

| Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) mm | 22 (20–25) | 27 (±3.6) |

| Fractional area change (FAC) % | 48.5 (43.75–52.25) | 60 (±6.5) |

| TR gradient mmHg | 21 (17–45) | 44 (36–50) |

Table 4.

Procedure results

| Procedure details—Results | HPSE population (n = 727) | DSE population (n = 105) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| THR achieved % (n) | 92.2% (670) | 79% (83) | <0.0001 |

| MHR achieved % (n) | 24.9% (181) | 5.7% (6) | <0.0001 |

| MHR achieved among patients reaching THR % (n) | 27% (181/670) | 7% (6/83) | <0.0001 |

| Exercise time (min) | 11 (9–13.5) | ||

| Maximum workload (watts) | 100 (75–125) | ||

| Elderly population | |||

| Age ≧ 80 | |||

| THR achieved % (n) | 93.5% (43/46) | ||

| MHR achieved % (n) | 52.2% (24/46) | ||

| Age < 80 ≧ 70 | |||

| THR achieved % (n) | 95% (134/141) | ||

| MHR achieved % (n) | 50.4% (71/141) |

The elder patients did not differ from the main HP cohort. Hybrid protocol resulted in high rates of THR achievement among patients between those 70 and 80 y old (131/141, 95%) and older than 80 years (43/46, 93.5%).

Ischaemia assessment

Out of 727, 192 (26.4%) of studies were positive for inducible regional dysfunction, the distribution of the number of segments involved is displayed in Supplementary data online, Table S1. Out of 727, 527 (72.5%) of the studies were negative and 6 (0.8%) were inconclusive. The reasons for inconclusive studies are displayed in Supplementary data online, Table S2.

Concomitant findings

The extension of the image acquisition to 10 images per stage allowed the identification of concomitant cardiac pathology. Significant non-ischaemic findings during hybrid protocol were identified in 114/727 (15.7%) of studies (Table 5). Out of 727, 64 (8.8%) of patients developed left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) or intraventricular gradients on CW Doppler assessment and 50/727 (6.9%) developed changes in diastolic function.

Table 5.

Non-ischaemic assessment

| Concomitant findings | |

|---|---|

| Total % (n) | 15.7 (114) |

| Dynamic LVOT gradient % (n) | 1.1 (8) |

| LV intraventricular gradient % (n) | 7.7 (56) |

| Change in LV filling pressures % (n) | 6.9 (50) |

Complications

There was 1/727 (0.14%) case of severe arrhythmia (idioventricular rhythm), 5/727 (0.7%) patients developed vasovagal episodes, and 14/727 (1.9%) had a hypertensive response to exercise (Table 6).

Table 6.

Complications

| Periprocedural complications | |

|---|---|

| Significant arrhythmia % (n) | 0.14 (1) |

| Vasovagal episode % (n) | 0.7 (5) |

| Hypertensive response % (n) | 1.9 (14) |

Conclusion

In this prospective analysis of consecutive 727 patients who underwent the novel HPSE 92% achieved THR with a low complications rate. 0.7% of patients experienced a vasovagal episode and 0.14% a severe tachyarrhythmia. Our findings suggest that this protocol is safe, feasible and has a high success rate in achieving THR.

Exercise is a preferred stressor in patients with suspected coronary artery disease as it is likely to reproduce daily symptoms and trigger ischaemic cascade in presence of obstructive coronary lesions.9 But it is perceived as a challenging and demanding technique,10 hence many laboratories use pharmacological SE even in patients who can exercise. Also, many patients, especially the elderly and those with complex comorbid profile are often limited in their mobility.11 Treadmill stress protocol requires certain agility from patients to get on and off the treadmill for swift image acquisition and supine bicycle stress protocol is reported to be terminated early due to muscular soreness caused by pedalling.12 These limitations were attenuated with the hybrid protocol. Unlike the majority of reported SE with relatively young male patients with normal body habitus13,14 our cohort included large proportion of elderly (26%) and those with obesity (33%) who managed to achieve THR. The exercise element of HPSE offers valuable insight into other factors such as lung function, the general health, nutritional status, and orthopaedic restrictions which is pivotal in risk stratification, particularly if patients are undergoing cardiac and non-cardiac interventions.15 The presence of intravenous cannula allowed to use contrast to enhance the endocardial border definition.16

Pharmacological stress is an established alternative, but complications are not infrequent, many of which lead to early termination without achieving the THR.6 The inconclusive results usually lead to further testing and delay in defining management plan. In the 105 consecutive patients at our centre who underwent DSE prior to our hybrid protocol only 79% achieved a THR which was significantly less than in HPSE group. The management of side effects is often prolonged and distresses patients on both ends—experiencing side effects and waiting longer for their diagnostic tests due to disruption of the stress lists. By avoiding these side effects while maintaining a high success rate we benefited our patients and the management of our stress echo laboratory. Another advantage of this protocol is that none of our patients were administered atropine to facilitate the achievement of THR. The use of atropine is related to a longer recovery time, can elevate the incidence of side effects due to paralysis of vagal control and is often associated with adverse sensations experienced by patients.6 Furthermore, it can restrict their ability to drive following the test.

With more subtle breathing effort, less respiratory related artefacts and less dobutamine associated side-effects, there is sufficient time during each stage for extended image acquisition. In our protocol, we included 2D images of the right ventricle and Doppler data for diastolic function and pulmonary pressures. Hence, we identified significant non-ischaemic findings in 15.7% of our patients.

The limitation of our study is the pragmatic design, which is based on clinical needs, hence it is not possible to fully establish the sensitivity of our protocol in the detection of flow-limiting coronary artery disease given that coronary angiography cannot be performed for the entire study population. In general, given the established accuracy of both dobutamine and exercise SE we did not seek ethical approval to conduct invasive coronary angiography.17 Nevertheless, among the 122 patients with positive studies who underwent angiography 102/122 (83.6%) had significant coronary disease. This is significantly higher than the data from the UK-wide EVAREST study involving 31 participating hospitals which demonstrated that only 55% of the positive studies (208/378) were found to have obstructive coronary artery disease on invasive angiography. The predominant protocol was DSE (73%) involving 5131 patients.18 In the future, non-invasive coronary imaging may be an avenue to investigate this, at least it is worth performing sub-group analysis.

In summary, our hybrid stress protocol for the evaluation of ischaemia is a safe and a feasible alternative to existing stress echo protocols. It allows acquisition of wider image data to assess for non-ischaemic cause of chest pain and shortness of breath. We have grown in our experience and confidence in HPSE and would advocate strongly for its use outside of our centre to benefit both patients and those involved in the management of stress echo laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Konstantinos Vakalis, Department of Echocardiography, Harefield Hospital, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals (part of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), Hill End Rd, Harefield, Uxbridge UB9 6JH, UK.

Max Berrill, Department of Echocardiography, Harefield Hospital, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals (part of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), Hill End Rd, Harefield, Uxbridge UB9 6JH, UK.

Majimen Jimeno, Department of Echocardiography, Harefield Hospital, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals (part of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), Hill End Rd, Harefield, Uxbridge UB9 6JH, UK.

Ruth Chester, Department of Echocardiography, Harefield Hospital, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals (part of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), Hill End Rd, Harefield, Uxbridge UB9 6JH, UK.

Shelley Rahman-Haley, Department of Echocardiography, Harefield Hospital, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals (part of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), Hill End Rd, Harefield, Uxbridge UB9 6JH, UK.

Anthony Barron, Department of Echocardiography, Harefield Hospital, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals (part of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), Hill End Rd, Harefield, Uxbridge UB9 6JH, UK.

Aigul Baltabaeva, Department of Echocardiography, Harefield Hospital, Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals (part of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), Hill End Rd, Harefield, Uxbridge UB9 6JH, UK.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at European Heart Journal - Imaging Methods and Practice online.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained for the patient whose echocardiographic images and videos are included in the manuscript.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

Anonymized clinical metadata, source code used for analysis, and supplemental figures and tables are available at contacting with the first author. Guys and St Thomas’ Electronic Research Records Interface (GERRI) is governed by the overarching Clinical Research Analytics Governance Group (CRAG). The CRAG welcomes specific and detailed proposals under the ethical clearance of GERRI. Initial enquiries should be directed to Finola Higgins (CRAG Manager) Finola.higgins@kcl.ac.uk.

Lead author biography

Dr Konstantinos Vakalis is a consultant cardiologist in London, UK at Queen Elizabeth Hospital (Lewisham and Greenwich NHS trust) and at Harefield Hospital (Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust). He was trained in cardiology in Greece and in the UK. He has been awarded the honorary title of Fellow of the European Cardiology Society (FESC) and Fellow of the European Society of Cardiovascular Imaging (FEACVI). His main interests in cardiology include imaging and heart failure. His clinical expertise is stress echocardiography. He is the heart failure lead at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

References

- 1.Leischik R, Dworrak B, Cremer T, Amirie S, Littwitz H. Stress echocardiography and its central role in cardiac diagnostics. Herz 2017;42:279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marwick TH. Stress echocardiography. Heart 2003;89:113–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee A, Newman DR, Van den Bruel A, Heneghan C. Diagnostic accuracy of exercise stress testing for coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:477–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sicari R, Nihogiannopoulos P, Evangelista A, Kasprzak J, Lancellotti P, Poldermans Det al. Stress echocardiography expert consensus statement: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC). Eur J Echocardiogr 2008;9:415–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pellikka PA, Arruda-Olson A, Chaudhry AF, Hui Chen M, Marshall JE, Porter Tet al. Guidelines for performance, interpretation, and application of stress echocardiography in ischemic heart disease: from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2020;33:1–41.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geleijnse ML, Krenning BJ, Nemes A, van Dalen BM, Soliman OI, Ten Cate FJet al. Incidence, pathophysiology, and treatment of complications during dobutamine-atropine stress echocardiography. Circulation 2010;121:1756–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Picano E, Mathias W Jr, Pingitore A, Bigi R, Previtali M. Safety and tolerability of dobutamine-atropine stress echocardiography: a prospective, multicentre study. Lancet 1994;344:1190–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadoglou N, Papadopoulos CH, Papadopoulos KG, Karagiannis S, Karabinos I, Loizos Set al. Updated knowledge and practical implementations of stress echocardiography in ischemic and non-ischemic cardiac diseases: an expert consensus of the Working Group of Echocardiography of the Hellenic Society of Cardiology. Hellenic J Cardiol 2022;64:30–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senior R, Monaghan M, Becher H, Mayet J, Nihoyannopoulos P; British Society of Echocardiography . Stress echocardiography for the diagnosis and risk stratification of patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease: a critical appraisal. Supported by the British Society of Echocardiography. Heart, 2005;91:427–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bairey CN, Rozanski A, Berman DS. Exercise echocardiography: ready or not? J Am Coll Cardiol 1988;11:1355–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, Buszman P, Camici PG, Crea Fet al. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: the Task Force on the management of stable angina pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1341–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbieri A, Bursi F, Santangelo G, Mantovani F. Exercise stress echocardiography for stable coronary artery disease: succumbed to the modern conceptual revolution or still alive and kicking? Rev Cardiovasc Med 2022;23:275. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olmos LI, Dakik H, Gordon R, Dunn JK, Verani MS, Quinones MAet al. Long-term prognostic value of exercise echocardiography compared with exercise 201Tl, ECG, and clinical variables in patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Circulation 1998;98:2679–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Supariwala A, Makani H, Kahan J, Pierce M, Bajwa F, Dukkipati SSet al. Feasibility and prognostic value of stress echocardiography in obese, morbidly obese, and super obese patients referred for bariatric surgery. Echocardiography 2014;31:879–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, Do D, Partington S, Atwood JE. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Medicine 2002;346:793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senior R, Dwivedi G, Hayat S, Keng Lim T.. Clinical benefits of contrast-enhanced echocardiography during rest and stress examinations. Eur J Echocardiogr 2005;6:S6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain M, Haley S, Baltabaeva A. New hybrid stress echocardiography protocol: a non-inferiority study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1583. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodard W, Dockerill C, McCourt A, Upton R, O’Driscoll J, Balkhausen Ket al. Real-world performance and accuracy of stress echocardiography: the EVAREST observational multi-centre study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2022;23:689–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized clinical metadata, source code used for analysis, and supplemental figures and tables are available at contacting with the first author. Guys and St Thomas’ Electronic Research Records Interface (GERRI) is governed by the overarching Clinical Research Analytics Governance Group (CRAG). The CRAG welcomes specific and detailed proposals under the ethical clearance of GERRI. Initial enquiries should be directed to Finola Higgins (CRAG Manager) Finola.higgins@kcl.ac.uk.