Abstract

Several Canadian provincial cancer agencies have adopted a nurse-led model of patient navigation to decrease care fragmentation in the system. The scope of competencies of the oncology nurse navigator (ONN) in Canada has evolved over the years in response to emerging cancer care challenges. This integrative review aimed to outline the scope of competencies of the ONN role in Canada. Three databases were searched since its inception to identify Canadian studies or theoretical papers on the role of ONNs. The search yielded 62 articles of which 39 were included in the review. Three interdependent role domains were identified. The first domain of care coordinator highlighted the ONN as a coordinator of health and practical needs along the care journey. The second framed the ONN as a change agent, through increasing patients’ health literacy, creating partnerships, and trusting relationships. ONNs were also described as a supporter of wellbeing, or a champion of emotional, multidimensional needs, and a transformer of the context of care. All domains were central to the navigator’s success in addressing inequities in care and improving patient outcomes across care settings.

The burden of cancer affects all Canadians. One in two persons will develop cancer in their lifetime (Canadian Cancer Society, 2021) and one in four diagnosed is expected to die from the disease (Canadian Cancer Society, 2022). Today, more than 1.5 million people in Canada are living with and beyond cancer (Canadian Cancer Society, 2022). Disparities in cancer care disproportionally affect disadvantaged groups including First Nations, Inuit, Metis; people from low-income areas; and immigrant populations (Ahmed et al., 2015; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer [CPAC], 2020). Systemic barriers affecting access to care have contributed to inequitable rates in cancer screening, diagnosis, cancer treatment, and supportive services across Canada (Beben & Muirhead, 2016). In a cancer care system that prioritizes acute service delivery, cancer patients report challenges to engaging in culturally competent community-based services and programs (Beben & Muirhead, 2016; Lavoie et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2020).

In Canada’s cancer system, patients are increasingly required to manage their care across settings through multidisciplinary teams (Thorne & Truant, 2010). However, patients can be left processing, integrating, and managing information and their treatment delivery without the needed support along their cancer journeys (Trevillion et al., 2015). Exacerbating this dis-coordinated care issue, treatment models have shifted to a community-based model of care, placing an increased burden of care on people with cancer (Given et al., 2017). Patients can be left feeling distressed and confused in an increasingly decentralized and bewildering cancer care system (Lavoie et al., 2016).

Development of the Navigator Role

Patient navigation was first identified as a policy solution in the 1980s in response to systemic barriers affecting care, increased pain and suffering from cancer, and elevated mortality rates in underserved cancer populations across the United States (US; Freeman & Rodriguez, 2011; Pedersen & Hack, 2011). Throughout the past two decades, navigation has been introduced by several Canadian provincial cancer agencies, refining the US community-based approach through a professional, nurse-led model of care (Pedersen & Hack, 2011). Now, several provinces have recognized nurse-led navigation as a central component in delivering high-quality, person-centred coordinated cancer care (Haase et al., 2020; Watson et al., 2016a, 2016b).

Problem Identification

The Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology (CANO/ ACIO) highlighted, in their 2020 position statement on patient navigation, that in Canadian navigation programs, the oncology nurse navigator (ONN) must 1) facilitate continuity of care, 2) teach and coach, and 3) develop supportive and therapeutic relationships. Two ONN role frameworks have been developed in Canada that further outline the core competencies of the ONN, including Fillion et al.’s (2012a) and the British Columbia Patient Navigation Model. However, the CANO/ACIO position statement and the two frameworks have not clarified the full scope of competencies for the ONN. To our knowledge, at the time of this review, no integrative reviews had been completed comparing and contrasting the roles and responsibilities of the ONN in Canada. To address this knowledge gap, our integrative review aimed to illuminate dimensions of the navigator role in a Canadian context and explore how the ONN contributes to decreasing barriers to accessing healthcare services.

METHODS

The integrative review summarizes empirical and/or theoretical literature to provide a holistic understanding of a healthcare issue (Broome, 1993). This type of review allows for the analysis of diverse methodologies. To increase rigour, we followed a four-step process of data reduction, data comparison, conclusion drawing, and verification, based on Whittemore and Knalf’s (2005) integrative review framework.

Information Sources and Search

The search process involved a comprehensive computer-assisted search strategy across three databases including the Medical Literature Online (MEDLINE), the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Scopus. The search was limited to Canadian studies published since the inception of the ONN role in Canada (2006). With the assistance of a Health Sciences librarian, a search strategy was developed with the following terms: nurs* N3 navigat* AND oncology* or cancer* or neoplasm* AND Canada or Canadian* or Alberta* or “British Columbia*” or Manitoba* or Saskatchewan* or “New Brunswick*” or “Nova Scotia*” or “Prince Edward Island*” or Newfoundland* or Quebec* or Yukon* or Nunavut* or “Northwest Territories*”.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria involved theoretical and empirical studies that were: (a) focused on ONNs, a Canadian context, and cancer populations, (b) accessible (i.e., via the University of Alberta online Library or the Inter Library Loan service), (c) online articles published in full, and (d) in English. The exclusion criteria included dissertations, theses, manuals, protocols, articles that explored other navigation models (e.g., non-nurse or lay navigators), and articles written in other languages. The search was performed in June 2021. One reviewer (JK) screened titles and abstracts and the full text of potentially eligible articles.

Data Analysis

Between June 2021 and September 2021, we employed a constant comparative method to refine the themes and categories concerning the ONN role and contribution to reducing barriers in care. Initially, data were extracted including title, author, year, context, purpose, study populations, methodology, roles, and the experience of the patients/families. An Excel sheet was used for recording data extraction. A matrix was created by the first author, allowing for data comparison and initial synthesis and interpretation of data. Data were iteratively examined to identify recurring patterns and themes, which were displayed in a diagram. The second author guided the data extraction and participated in the analysis. The matrix was synthesized several times, and the themes categorized under three broad domains that outlined the navigator role dimensions.

RESULTS

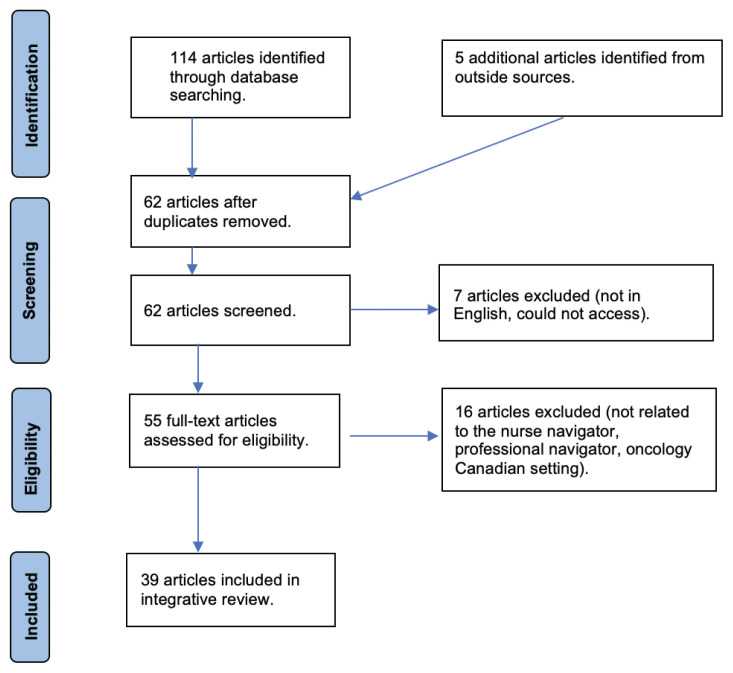

In July 2021, the database search yielded 110 results. After 52 duplicates were removed, the titles and abstracts of 58 search results were screened. This resulted in 51 articles being selected for full-text review. Of these, 32 articles were included in the final analysis. An additional five articles were identified through a hand search strategy and a review of the reference lists of included articles. In June 2023, we conducted a search update to identify articles published from 2021 to 2023. From the four articles identified and screened, two were selected for inclusion in the review. In total, 39 articles were included in this analysis. A diagram outlining the search and inclusion process is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prisma Flow Diagram

Overview of Included Articles

The final 39 articles included qualitative (n = 17), quantitative (n = 10), and theoretical (n = 12) papers. All articles were published from 2006 to 2023. The studies predominately involved two populations, Indigenous peoples and those living in rural communities. Cancer types varied, but the authors primarily included people with breast, colorectal, lung, and advanced cancer. The articles reported the ONN role across various Canadian provinces (n = 3), Ontario, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland (n = 2), and Quebec and Nova Scotia (n = 2); or in one province including Alberta (n = 3), British Columbia (n = 5), Manitoba (n = 2), Newfoundland (n = 1), Nova Scotia (n = 2), Ontario (n = 6), and Quebec (n = 13). See Table 1 for an overview of the included articles.

Table 1.

Overview of the Included Articles

| Authors & Date | Methodology | Purpose | Populations and Province | Roles and Responsibilities of the Oncology Nurse Navigator (ONN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baliski et al. (2014) | Quantitative study | To determine the impact that the Interior Breast Rapid Investigation Diagnose program (IB-RAPiD) (i.e., organized by the nurse navigator) had on wait times for the centre, and to identify areas where improvements could be made in the care path. | Breast cancer patients in British Columbia | The program was organized by the navigator. The navigator held several roles, such as facilitating all relevant imaging tests and image-guided biopsies and obtaining pathology reports expediting surgical referrals (coordinated care). They also provided information and support to patients and the family, in the form of one-on-one meetings, along with group educational events involving other healthcare providers. |

| Blais (2008) | Theoretical paper | To investigate and highlight the importance of the nurse navigator in supporting patients and their families through the health care system. | Varied cancer patients in Alberta | ONNs acted as patient liaisons, providing specialized nursing care using a broad knowledge base. They provided access to resources and services, and empowered patients to make informed decisions. This was achieved through providing education, information, guidance, emotional support, and psychological assistance. |

| Blais et al. (2014) | Qualitative study | To document the characteristics of patients in terms of the prevalence of distress/problems/symptoms they reported, in addition to the support they wanted versus the support they were offered at the time of their first meeting with nurse navigators, 2) to identify the factors that are the most strongly associated with distress 3) to verify whether the cutoff score on the tool used to orient patients (on the basis of their reported distress) was optimal. | Varied cancer patients in Quebec | Identifying and acknowledging patients’ needs/concerns was an intervention in itself, and a central responsibility of the navigator. Actively listening to and supporting patients in solving their identified problems was a key role of the ONN. Therefore, ONNs were identified as needing to establish dialogue and an open relationship with patients. Navigators required basic communication skills to establish the therapeutic relationship and provide psychosocial care. |

| Campbell (2016) | Theoretical paper | Outlined a proposal to create a cancer therapy nurse navigator role. | Oral cancer patients in Ontario | The authors investigated a registered nurse model of care to provide education, coaching, support, and navigation for patients and their caregivers. Several responsibilities outlined for the ONN included meeting with patients/caregivers to identify barriers to care, referring patients to supportive teams (e.g., social worker, dietician), providing education to patients/ caregivers, communicating and verifying treatments with patients on the start day of therapy, assess for side effects and provide therapeutic advice, scheduling exams or consultations, arrange for follow-ups based on assessments, participate in monthly visits with oncologists, triage for symptoms, help patients navigate the healthcare system, and provide outreach education to retail pharmacies. |

| Cha et al. (2020) | Quantitative study | To monitor the impact of the centralized intake for surgical referral and triaging on wait times for definitive surgery for patients with breast cancer using navigators. | Breast cancer patients in British Columbia | Patient navigators reviewed all referrals and investigations to triage patients and referred patients to breast physicians for assessment and surgeons for tumour excision. |

| Common et al. (2018) | Quantitative study | To determine if the Thoracic Triage Panel (TTP) reduced wait times for lung cancer diagnosis and treatment, and if it led to more appropriate specialist consultations than the traditional, primary care provider-led referral process. | Lung cancer patients in Newfoundland | The nurse navigator developed personal relationships with patients and communicated the team’s plans at weekly meetings. Therefore, the nurse navigator coordinated patient care and acted as the contact person for patients and clinicians involved in the program. |

| Cook et al. (2013) | Theoretical paper | To identify the core areas of practice and associated competencies for professional cancer navigators that were considered integral to optimizing patient and family empowerment and facilitating continuity of care. | Varied cancer patients across Canada | Based on a synthesis of evidence, the ONN operated within three core areas of practice. One, providing information and education, and two, providing emotional and supportive care. This role included the ability to identify problems and issues causing distress, and offer clinical interventions to help manage issues (i.e., engaging in conversations, using tools to explore fears and anxieties about disease progression). And three, coordinating services and continuity of care within the context of an interdisciplinary team approach. Screening, treatments, and supportive care were all provided by different providers and in different settings. Therefore, the navigator supported patients throughout the continuum and created continuity at key points, including diagnosis, transition into active treatment, to survivorship and palliative care. They served as the link between patient/care team/hospital/care services. |

| Crawford et al. (2013) | Theoretical paper | To describe the design, development, and evaluation of the “Patient Navigation in Oncology Nursing Practice” course. | Varied cancer patients across Canada | The ONN program taught knowledge and skills in seven key domains of the role, including supportive care (i.e., assessing the needs of patients and families), care planning, communication, attending to patient’s emotional states, addressing patients’ concerns, patient education, valuing culture and diversity, assessing available social supports, community resources, and services. |

| Duthie et al. (2017) | Qualitative study | To explore cancer patients’ experiences with multimodal treatments, as well as issues related to navigating the care system. | Colorectal, breast, B cell lymphoma, endometrial, prostate, multiple myeloma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients in Quebec | The ONN accompanied and supported patients and families throughout the trajectory of the cancer experience. The ONN accompanied patients with complex needs throughout their cancer journey (i.e., accessing and managing physical needs, providing information and education, providing support, and coordinating care). They were described as facilitators of communications among providers, acting as the point of focus at the centre of the healthcare wheel. |

| Etchegary et al. (2022) | Qualitative study | To understand the experiences and preferences of cancer predisposition syndromes (CPS) carriers, as this would inform how a nurse-led navigation program is best suited to meet their individualized needs. | Patients living in Newfoundland with a history of any molecularly confirmed hereditary cancer syndrome or a combination of any hereditary cancer genes | ONN programs were identified as patient centred, aimed at reducing fragmentation and barriers patients face within the cancer care system. The authors identified the key responsibilities of ONNs were to communicate among team members, provide supportive care, and coordinate care. Navigators were also involved in providing education to patients on health promotion activities (e.g., screening for genetic mutations). The authors also highlighted that the scope of navigators varied across care models, but their primary function of increasing access to care was common across all. |

| Fillion et al. (2006) | Qualitative study | To propose a profile for the role and function of an oncology patient navigator nurse (OPN) and to assess its implementation in a specialized team within a university hospital centre with a supraregional model for oncology. Specific objectives were to describe 1) the role and functions of an OPN, 2) role outcomes on the process of adaption to illness for individuals with cancer and their families, 3) role outcomes on continuity of care and services delivered by the interdisciplinary team and crew network. | Head and neck cancer patients in Quebec | Four functions were linked to the role of the OPN for individuals with cancer and their families. One, to assess the needs and follow up on the interventions implemented throughout the initial assessment, two to inform and teach, three to provide special support and attention and four, to coordinate and promote continuity of care, services, information, and therapeutic relationships. All functions and scopes of the role were flexible to encourage respect for the culture and service model in the setting, and to avoid duplication of services and roles of various caregivers. |

| Fillion et al. (2010) | Qualitative study | To assess the implementation of oncology nurse navigators within two local joint teams. The study’s objective was to describe the implementation process from the perspectives of the stakeholders involved. | Varied cancer patients in Quebec | The authors described the role of the ONN was vague in relation to its clinical and organizational components. However, the authors particularly highlighted the empowerment role and that patient navigators improved care coordination and the patient’s understanding of the healthcare system and the care trajectory. |

| Fillion et al. (2011) | Qualitative study | To describe the perceptions of implementing the Screening for Distress tool within professional cancer navigators from the perspective of key actors before and after it’s implementation in the Quebec and Nova Scotia provinces. | Varied cancer patients in Nova Scotia and Quebec | The ONN was described as a professional role, used to facilitate continuity of care and promote patient empowerment. Navigators offered patients/families/caregivers assistance through the maze of services to promote the best possible outcomes and quality of life, through all phases of the cancer experience. The authors identified medical and biopsychosocial care coordination as central to the role. |

| Fillion et al. (2012a) | Qualitative study | To elaborate, refine, and validate the content of the bidimensional framework for patient navigation in a Canadian context. | Varied cancer patients in Nova Scotia and Quebec | Professional cancer navigators aimed to ease and expedite patients’ access to services and resources, improve continuity and coordination of care throughout the cancer continuum, and serve as a patient advocate. The patient navigator role was illustrated in two dimensions, including firstly promoting continuity of care (i.e., responding to patient needs and tailoring interventions). The second dimension was empowerment. This involved promoting active coping, cancer self management (i.e., supporting patient’s ability to accept the illness and regain control), and supportive care (i.e., meeting physical, emotional, psychological, social, and spiritual needs). |

| Gilbert et al. (2011) | Qualitative study | To explore the phenomena of patient navigation in depth. Specifically, the definition of patient navigation, how navigation benefits patient care, the role of nurses in patient navigation in the diagnostic period, the education/training needed to develop the knowledge and skills to navigate, and the role of other members of the healthcare team in patient navigation. | Varied cancer patients in Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Manitoba | Four roles of the patient navigator were highlighted, including primarily coordination of care (i.e., providing information and coordination during the care journey), improving patient outcomes (i.e., decreasing anxiety and increasing satisfaction in areas of greatest impact on the patient), and creating partnerships. Patient navigators collaborated with various clinicians involved in cancer diagnosis and treatment to create system improvements. Patient navigators facilitated patient navigation along the patient pathway. Some navigators improved the pathway by pre-booking appointments and expediting diagnostic procedures. |

| Haase et al. (2020) | Theoretical paper | To provide a historical analysis of the development of the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology position statement on Cancer Patient Navigation. | Evaluated the Cancer Patient Navigation (CPN) role across Canada | ONNs created care that was personalized, coordinative, enabling, and person-centred (i.e., promoting dignity, compassion, and respect). Care was described as tailored, coordinated across time, supportive of patients’ changing needs, enabled self management, supportive, and involved in treating patients with dignity, respect, and compassion. |

| Hebert & Fillion (2011a) | Qualitative study | To better understand the oncology nurse navigators’ support function, first from the perspective of the individuals living with cancer, and second from the perspective of the ONNs themselves. The objective was to understand the perspectives of people living with cancer, the nature of their needs, and the support provided by the oncology nurse navigator along the disease trajectory. | Varied cancer patients in Quebec | The patient navigator assesed the patient’s needs and provided support through targeted interventions. The patient navigator was identified as being present along the care trajectory to meet the emotional needs and form trusting relationships with patients. The navigator must also provide information (information support) continuously along the care journeys. |

| Hebert & Fillion (2011b) | Qualitative study | To explore and describe from the perspective of the oncology nurse navigator the support interventions provided to those living with cancer and their families throughout the care trajectory. | Varied cancer patients in Quebec | The functions of the ONN were assessing, teaching and informing, supporting, and coordinating. The authors described the nature of the support function required clarification. The navigator created support interventions to meet practical needs (i.e., coordinated activities for appointments/exams, services), information needs (i.e., facilitate decision making, promote development of skills such as coping), emotional needs (i.e., crafting a sense of belonging, reassurance, feeling emotionally sound), physical needs (i.e., management of physical symptoms and discomforts), psychosocial needs (i.e., consolidate coping strategies), and spiritual needs (i.e., meeting needs related to personal values, priorities, and hopes). |

| Jeyathevan et al. (2017) | Qualitative study | To explore the role of oncology nurse navigators in enhancing patient empowerment for adult patients with lung cancer during the diagnostic phase of cancer care. | Varied cancer patients in Ontario | The clinical functions of the ONN roles were determined based on patients’ perceptions of how the ONN impacted patients and the family’s level of empowerment, in relation to their use of active coping, supporting self-management, and supportive care. Promoting active coping in patients was a central strategy used by ONNs to remove stressors from the patients during the diagnostic phase. This was achieved through acting as a patient advocate and providing educational supports. |

| Kammili et al. (2023) | Quantitative study | To examine the impact of a corridor of care between rural and urban areas on gastric cancer outcomes by comparing rural versus urban patients treated at a centralized referral centre. | Gastric cancer patients in Montreal | Pivot nurses (navigators) were assigned to all cancer patients and coordinated care among multidisciplinary teams. They acted as the interface between the patient, care team, family, and other health services. Select responsibilities included coordinating blood work, consultations, therapies, and follow-up appointments throughout the care trajectory. Care was described as individualized and met the patient’s preferences, expectations, and needs. The pivot nurse achieved this by communicating with all care providers a consistent vision for the care plan. |

| Kuzmarov et al. (2011) | Theoretical paper | To analyze the development of a multidisciplinary anti-cancer model, for a hospital and it’s network in the province of Quebec, focusing on the evolving ONN’s roles among the geriatric population faced with cancer. | Varied cancer patients in Quebec | Trained nurse navigators played a ‘central role’ in providing supportive care and expert guidance, assisting the patient/family in navigating the healthcare system and providing information and education. |

| Lavoie et al. (2016) | Qualitative study | To explore how the context of First Nations people’s lives intersect with structural barriers to shape their access to care and expectations of cancer care. | Breast cancer patients in Manitoba | The patient navigator role was used to support continuity of care. Patient navigation programs had significant positive impacts on continuity of care where barriers prevent patients from navigating an existing and functioning system. |

| Loiselle et al. (2020) | Quantitative study | To report on participants’ cancer care experiences and satisfaction according to their perceptions of being assigned to a nurse navigator (NN) and to compare NN/non NN groups across the six cancer care domains: emotional support, coordination and continuity of care, respect for patient preferences, physical comfort, information, communication and education, access to care, as well as four main nursing functions (i.e., assessment, education, support, coordination). | Varied cancer patients in Ontario | Nurse navigators were considered essential members of the oncology multidisciplinary team in Quebec to support patient-centred care. The role included four main functions including assessing patient needs, providing education and information, supporting patients and family members, and coordinating care. |

| Marchand (2010) | Theoretical paper | To explore the application and the growth of the concept navigation within the Canadian health care system. The author also aimed to outline the challenges and successes of the nurse navigator role in the development of a formal provincial breast assessment program. | Breast cancer patients in Quebec | Identified the role of the navigator must fluidly assume the competencies of the clinical nurse specialist, including clinical, research, leadership, and consultant/collaboration. The central roles/responsibilities of the nurse navigator role were to enhance and bridge interdisciplinary interactions and communication, guide patients proactively through diagnostics (i.e., with adherence to targeted timelines), provide education on the patient’s health care and disease process, facilitate referral to allied health members such as social work, and review data and facilitate knowledge transfer to all parties. |

| Melhelm & Daneault (2017) | Qualitative study | To explore the needs of cancer patients in palliative care and to determine how care providers could meet these needs more fully. | Varied cancer patients in Quebec | Six roles of the ONN were outlined, including ensuring the patient understood their diagnosis, being present after they heard the diagnosis, consulting with the oncologist or family physician, following the patient (i.e., from the moment of the diagnosis of cancer), providing the patient with emotional support (i.e., validating their feelings, referring patients to professionals), listening attentively (i.e., being present), ensuring the patient was comfortable, and being proactive in cooperating and communicating with other providers. |

| Miller et al. (2021) | Qualitative study | To identify patient factors associated with a greater need for navigation, according to the views of nurse navigators in Nova Scotia. | Varied cancer patients in Nova Scotia | Cancer patient navigators (CPNs) had three primary roles: psychosocial and practical, informational and coordination of care. The psychosocial and practical roles included providing emotional support and helping patients arrange the practical aspects of accessing cancer care (i.e., travel, lodging for cancer treatments, applying for low-income assistance programs, and paying for some treatments and prostheses). The informational role included activities such as reviewing diagnostic and treatment information with patients. The coordination of care role involved communicating with the health care team regularly, and following up on healthcare decisions on behalf of/ assistance to the patient. |

| Park et al. (2018) | Quantitative study | To investigate of individuals diagnosed with cancer who died in Nova Scotia during 2011 to 2014, how do adult descendants who were navigation enrollees differ from those who were not. | End of life cancer patients in Nova Scotia | The goal of navigation was to ensure timely, up-to-date, coordinated patient-centred care. They also were involved in meeting advanced care planning and palliative end-of-care needs. The role contained three domains, including patient education, psychosocial and practical support, and coordination of care. |

| Pedersen & Hack (2011) | Theoretical paper | To answer three questions to facilitate refinement of the British Columbian model of navigation. 1) What are the stakeholders needs and perspectives, 2) What are the core functions and best practices of current navigators, and 3) What models and theories should guide and inform navigation practice and evaluation? | Varied cancer patients in British Columbia | One key assumption of the BCPNM (British Columbian navigator framework) was that patients and families required information and emotional support to feel prepared. This was classified as one of the main goals of navigation. Four central roles were identified based on this goal, including facilitating linkage to health care resources, facilitating decision-making of patients, improving access to practical assistance, and identifying/developing community supports. |

| Pedersen et al. (2014) | Qualitative study | To delineate the role of the oncology nurse navigator, drawing from the experiences and descriptions of younger women with breast cancer. | Breast cancer patients in Manitoba | Supporting patients during times of uncertainty (i.e., having someone assisting them through the oncology treatment process and providing direction related to other aspects of care throughout the entire illness trajectory) was identified as a key role of the NN. Navigators were identified as someone who must know the cancer system, patient resources, and understand the medical side of breast cancer. |

| Plante & Joannette (2009a) | Theoretical paper | To explain why nurses were selected as patient navigators and to describe how the role was integrated in the Monteregie region. | Varied cancer patients in Quebec | ONNs offered and facilitated social supports, decision supports, active coping, and fostered patients’ self-efficacy. ONNS used a holistic approach when engaging with both the patient and their family (i.e., empowering patients), managing system issues, and developing a care team. The nurse navigator-initiated changes in the care philosophy and structured changes within the organization by evaluating and supporting patients’ needs. |

| Plante & Joannette (2009b) | Theoretical paper | To describe the role of IPOs (Quebec’s Oncology nurse navigators) in practice, the problems encountered in various care contexts, and the solutions brought forward to facilitate their implementation. | Varied cancer patients in Quebec | Identified the ONN’s role was understood by the cancer team. The role involved evaluating the needs of patients with cancer and their families, presenting new cases to the team at interdisciplinary meetings, and engaging the team in developing a plan for interdisciplinary interventions. NNs also acted as agents of change to address existing clinical and organizational problems (e.g., changes to the organization of care). |

| Richard et al. (2010) | Quantitative study | To add understanding to the measurement of patient satisfaction in a comprehensive cancer care centre (CCC) and to provide data to inform quality improvement initiatives that would result in greater satisfaction with care for cancer patients. | Varied cancer patients in Quebec | ONN interventions focused on providing patient-centred care, which led to increased patient satisfaction. The navigator guided the patient through the illness trajectory. Roles of the ONN included assessment and management of needs and symptoms, patient education, support to patients and their families, and ensuring continuity of care. |

| Ritvo et al. (2015) | Quantitative study | To analyze how much of an increase in screening rates could be accomplished with a personal navigation intervention. | Bowel and colorectal cancer patients in Ontario | The authors used a primary care outreach approach to arrange nurse navigation to increase colorectal cancer screening uptake. Each tailored nurse navigation intervention involved providing general information regarding colorectal cancer screening, reviewing colorectal screenings, and elucidating the participant’s preferred screening tests. |

| Roberts et al. (2020) | Theoretical paper | To describe the author’s experience as a First Nations, Inuit, and Metis (FNIM) nurse navigator. | Varied cancer patients in Ontario | The NN is a diverse, land-based, and patient-centred role. The position is generally non-clinical. It is not solely a case management role. The principle objective of the navigator was to establish trust with patients, act as the ‘link’ between the patient and the health care team, and as their advocate. |

| Srikanthan et al. (2016) | Quantitative study | To determine if the presence of a dedicated program for young breast cancer patients and a nurse navigator would be associated with an increased frequency of fertility discussions prior to the initiation of adjuvant or neoadjuvant systemic therapy. | Breast cancer patients in Ontario | The OCC program included the ONN; the ONN’s major role was to implement coordinative care management for patients. The nurse navigator screened referrals to the cancer center, contacted patients post-appointment, and followed women through diagnosis, treatment, and beyond. In addition to expediting tests/consultations, and providing ongoing support, the NN also raised and discussed age-related issues such as fertility, genetics, and sexual health. |

| Trevillion et al. (2015) | Qualitative study | To evaluate the effectiveness of breast cancer care support provided by breast cancer care navigators (BCCN) for women attending the breast health clinic. | Breast cancer patients in British Columbia | The BCCN (navigator) program aimed to provide appropriate information, education, and emotional support for patients who were newly diagnosed, undergoing treatments, or engaging in follow-up care. Their primary objective was to serve as liaison between the patient and their treatment providers. The second was to provide timely delivery of diagnostic, treatment, and follow-up services. |

| Watson et al. (2016a) | Theoretical paper | To develop an educational framework that guided the competency development and orientation for registered nurses hired into cancer patient navigation roles and how the framework evolved to support navigators from novices to experts. | Varied cancer patients in Alberta | The role of the NN involved facilitating continuity of care (i.e., informational continuity, management continuity, relational continuity), and promoting patient and family empowerment (i.e., active coping, cancer self-management, supportive care). The navigator role acted as a single point of contact for patients and families living with cancer, the community-based provider, and the cancer care system, aiming to integrate care across systems. |

| Watson et al. (2016b) | Qualitative study | To integrate the cancer patient navigator role into the existing clinical environment at each setting (15 sites across Alberta) and to evaluate its impact. | Varied cancer patients in Alberta | The navigator role provided meaningful support, as the navigator was able to focus their supportive interventions on what was an issue for the patient/family. The navigators identified their general roles were to enhance continuity of care, improve access to information, and provide person-centred care. |

| Zibrik et al. (2016) | Quantitative study | To improve referral practices, timelines, and availability of molecular testing for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. | Lung cancer patients in British Columbia | The role of the nurse navigator was to streamline the triaging process for patients with lung cancer by ensuring all appropriate interventions were initiated at the time of referral (e.g., radiologic and molecular tests), and arranging consultations. |

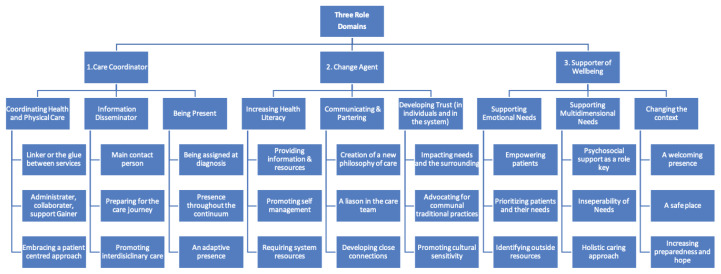

The ONN responsibilities described in the selected articles ranged across three domains, namely, 1) care coordinator, 2) agent of change, and 3) supporter of wellbeing. The choice of terminology used by the patients, family members, and authors to define the ONN varied. All role domains were described as fluid and interdependent in nature, and adaptive to the needs of people with cancer and contexts of care. All role domains assisted the navigator in decreasing barriers to cancer care, and supported the use of change orientated, patient-centred, and collaborative approaches with cancer populations. Below, an overview of each of the identified role domains is provided.

A. The ONN as a Care Coordinator

The care co-ordinator role referred to the ability of the ONN to facilitate timely access to care, including to appropriate specialized services and supportive resources. This care coordination role was a central responsibility of the ONN, as it directly addressed the physical barriers to care experienced by cancer patients (Gilbert et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2016b). Through the coordination of care, patients were prevented from “falling through the cracks,” such as missing referrals, follow-up checkups, and regular screenings (Etchegary et al., 2022; Pedersen & Hack, 2011; Gilbert et. al., 2010, p. 233). Care coordination also served to prevent poorer patient outcomes, longer lengths of stay, and increased costs on the healthcare system (Marchand, 2010). This role domain included coordinating across all health needs, being a disseminator of information and being present with the patient throughout the care journey.

A.1 Coordinating Health Needs

Care was coordinated through making referrals (i.e., for surgery, screenings, etc.) and the process of triaging to appropriate specialists (Kammili et al., 2023; Kuzmarov & Ferrante, 2011; Zibrik et al., 2016). Terminology used to describe the coordinator role included the ‘linker’, or the ‘glue’ between the patient, care team, hospital, and supportive care services (Haase et al., 2020; Lavoie et al., 2016; Marchand, 2010). This was achieved through collaborating with various providers and acting as a case coordinator (Marchand, 2010). The ONN ensured all patients received the right (specialized) services at the appropriate time throughout their care journey (Cha et al., 2020; Common et al., 2018; Kammili et al., 2023). This care coordinator role required skills in administrative leadership, collaboration, and the support of all stakeholders.

A.2 Disseminator of Information

The ONN was identified as the main contact person for all team members such as the oncologist, nurse, or specialists, among others (Ritvo et al., 2015). Several authors described this aspect of the role dimension as being a transmission belt of information, or a broker of knowledge (Crawford et al., 2013; Duthie et al., 2017; Fillion et al., 2012a; Marchand, 2010). Navigators managed the constant influx of information to direct care, taking opportunities to answer questions, provide resources, and ensure patient and care team members’ understanding (Fillion et al., 2012a). Information was tailored by the ONN to each care team member and provided at individual meetings or group sessions, facilitating group decision-making and coordination in care (Baliski et al., 2014; Blais, 2008).

Through the ONN’s managing the care team’s access to patient-related information and facilitating knowledge transfer to the right parties, patients reported decreased experiences of overwhelming emotions (Crawford et al., 2013; Pedersen & Hack, 2011). This decrease was related to reports of fewer experiences of information overload and an increased understanding of both medical- and non-medical-related information. Receiving translated information assisted patients in preparing for the cancer journey and helping to increase their information retention during future team meetings (Pedersen & Hack, 2011). The information translation role of the ONN therefore facilitated patients’ decision-making and engagement during these team sessions (Crawford et al., 2013).

A.3 Being Present throughout the Cancer Care Experience

Patients reported that the ONN was available at key transition points along the care trajectory (Park et al., 2018; Srikanthan et al., 2016). To manoeuvre their journey well, patients required an ONN to be assigned to the patients at diagnosis and be with them throughout the journey. The ONN involvement was referred to as “quarterbacking the cancer journey” (Pedersen et al., 2014, p. 80). This assignment, or constant connection with the ONN was illustrated in the articles reviewed as a pivotal feature of the role. The continued presence of the ONN, or their role as an ‘anchor’, ensured the patient’s unique and holistic needs were constantly addressed along the care continuum (Kammili et al., 2023; Loiselle et al., 2020; Watson et al., 2016a). The ONN presence was described as adaptative because it increased during times of uncertainty, such as at diagnostic appointments, and during care transitions (e.g., when requiring end-of-life care) (Pedersen et al., 2014; Pedersen & Hack, 2011).

B. The ONN as an Agent of Change

The role domain of change agent referred to the ONNs promotion of positive changes in the patient’s care trajectory and in the clinical setting (e.g., embrace a new care philosophy such as patient-centred) or empowering the patient to initiate required change. This role required navigators to have competencies in health promotion, professional leadership (i.e., being familiar with and mobilizing resources), teamwork, problem-solving, and an organizational change perspective (Fillion et al., 2006; Pedersen & Hack, 2011). The change agent role was described as central in the navigator’s ability to identify and address inequities or system inefficiencies along the care pathway. The change agent works through reporting, finding simple fixes, or creating partnerships with organizations or other care teams (Fillion et al., 2012a; Watson et al., 2016a). This involves crossing care boundaries, building partnerships, and transferring knowledge to various parties (Gilbert et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2016a). The navigator initiates these changes using, in particular, three methods, which include increasing health literacy (interactive and critical) to empower individuals, developing partnerships, and restoring trust among patients.

B.1 Increasing Health Literacy

At diagnosis, patients may experience limited health literacy (Jeyathevan et al., 2017). However, ONNs assisted in eliminating this barrier to care through 1) providing patients with information and community resources, and 2) including and empowering patients in the decision-making process (Jeyathevan et al., 2017; Pedersen & Hack, 2011). This resulted in the development of both interactive (i.e., development of personal communication skills) and critical health literacy (i.e., enhancing personal empowerment) (Blais, 2008; Jeyathevan et al., 2017; Plante & Joannette, 2009; Watson et al., 2016a). Through the provision of support and information by the ONN (i.e., using the process of awareness raising), patients developed the capacity to address care issues or systemic factors affecting access to care, such as income disparities and geographical barriers to health services (Miller et al., 2021). By empowering patients to navigate the inequities in care, the wait times for treatment in cancer care decreased, improving satisfaction in the cancer system (Cha et al., 2020).

B.2 Communicating and Creating Partnerships

Navigators advocated, communicated, and partnered with external agencies and within the care team to address the inequities in care that underserved populations faced (system issues) and improve patient outcomes (e.g., in Indigenous, rural, remote regions, or youth). ONNs acted as changes agents, or a catalyst in addressing the central needs of patients (i.e., a humanizing connection, personal support, etc.) through the creation of a patient-centred philosophy of care (Plante & Joannette, 2009a). Patients reported that the navigator’s ability to openly communicate with all team members became the “vital importance of the ONN [in the organization]” (Melhelm & Daneault, 2017, p. 540). Because of this close connection with the patient and multidisciplinary team members, the ONN had the ability to advance these relationships to initiate changes in individual care and at an organizational level (Baliski et al., 2014; Common et al., 2018; Roberts et al., 2020).

B.3 Developing Trust and Interpersonal Relationships

Care Team Collaborator

The navigator enhanced the unique abilities of each “spoke [member] on the care wheel [team]” (i.e., nursing, medicine, and other allied health professionals) to address complex patient issues (Duthie et al., 2017, p. 47). This collaborative change agent role required training in both verbal (Crawford et al., 2013), interpersonal (i.e., a humanizing communication method), and inter-disciplinary communication skills (i.e., active listening, non-violent approaches). Nurses therefore had to train in adapting their language to each patient or care team member (Plante & Joannette, 2009a). Through promoting the delivery of interventions collaboratively, navigators assisted persons with cancer and their families to maintain a sense of control (self-management) and quality of life while managing multiple care issues.

Developing Trust

The ONNs initiated change in various patient communities through giving “communities their own voice” (Roberts et al., 2020, p. 301). This was achieved through establishing a trusting relationship with the patient populations, asking questions sensitively, providing answers and encouragement, and understanding who the patients were as a person and what was important to them. This interpersonal trust assisted navigators in not only meeting patients’ direct needs, but positively impacting contextual factors in the community, such as overcoming organizational barriers to care. Finding creative ways to overcome resource shortages were specifically highlighted, including a lack of access to health care professionals, lack of facilities including supportive services at cancer agencies, and transportation services (Marchand, 2010; Plante & Joannette, 2009b; Trevillion et al., 2015).

The ONN also acted to rebuild patients’ trust within the health care system, particularly among underserved populations, such as immigrant families and with Indigenous, Metis, and First Nations peoples. Trust was built through the provision of culturally safe care and services (Lavoie et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2020). By facilitating patients to engage in both urban and community navigation, patients felt trusted, empowered, and knowledgeable about overcoming barriers to accessing care (Roberts et al., 2020). However, Lavoie et al., (2016) identified that other care providers must also take on the role of advocating for culturally sensitive services for patients, especially as the navigators’ caseloads increase with escalating cancer rates.

C. The ONN as a Supporter of Wellbeing

Patients described a central barrier in accessing care and experiencing satisfaction throughout their care journey was the anxiety and distress they experienced throughout cancer treatments (Blais et al., 2014; Gilbert et al., 2010; Lavoie et al., 2016; Pedersen et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2020). ONNs alleviated this distress through supporting patient needs in various dimensions (e.g., emotional, cognitive, physical). The ONN became not only a supporter of health, but also of wellbeing. This was illustrated in the navigator’s ability to help strengthen patients’ physically, psychologically, socially, and spiritually within family, friendships, and work (Blais, 2008; Roberts, 2020; Watson et al., 2016b).

C.1 Addressing Emotional Needs

In several articles, patients reported their emotional needs were unmet prior to accessing a nurse navigation program (Blais et al., 2014; Lavoie et al., 2016; Loiselle et al., 2020; Pedersen et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2020). For example, authors described patients feeling lost in their healthcare journey (Pedersen et al., 2014), and chronically worried without coping mechanisms to manage their condition (Lavoie et al., 2016; Pedersen & Hack, 2011; Roberts et al., 2020). To mitigate this emotional stress, ONNs empowered patients using three strategies: promoting coping (active and passive), emotional self-management, and social supports (Fillion et al., 2012a; Pedersen & Hack, 2011). Navigators addressed supportive needs through collaborating, identifying barriers to care (supportive needs), and facilitating the development of a plan of action with patients (Crawford et al., 2013).

C.2 Supporting Multidimensional Patient Needs

Various authors described the navigator as a supporter of needs (Blais et al., 2014; Cook et al., 2013; Crawford et al., 2013; Duthie et al., 2017; Fillion et al., 2006; Fillion et al., 2011; Gilbert et al., 2010; Hebert & Fillion., 2011a; Hebert & Fillion, 2011b; Kammili et al., 2023; Loiselle et al., 2020; Melhelm et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2021; Trevillion et al., 2015). The ONN supported patients’ emotional, practical, informational, and practical needs (Cook et al., 2013; Etchegary et al., 2022). Nurses followed a comprehensive multidimensional approach that included skills in communication, developing helping relationships, and upholding holistic views (Plante & Joannette; 2009a; Plante & Joannette, 2009b). Navigators promoted “positive perceptions of their [the cancer patients] care path” not as a result of the direct outcomes (e.g., decreasing wait times for surgery), or through the successful completion of an intervention, but through enacting a holistic caring approach (Baliski et al., 2014, p. 691; Richard et al., 2010).

C.3 Changing the Context

To understand the patients’ needs required placing the patient at the centre of care; in many instances this required a change in the philosophy of care in a setting (i.e., change agent role), through the development of a welcoming presence (Duthie et al., 2017, Crawford et al., 2013; Fillion et al., 2006; Melhem & Daneault, 2017) and a safe space (Richard et al., 2010; Trevillione et al., 2015). In this safe space, patients reported increased ease in sharing their feelings, thoughts, and priorities in care (Duthie et al., 2017). Restructuring this context of care, described by Marchand (2010) as the ‘surrounding’, was identified as particularly important in Indigenous communities. This restructuring process required the development of trust, empathy, and a ‘helping’ attitude towards the patient populations by the navigators (Fillion et al., 2006; Fillion et al., 2011b; Roberts et al., 2020; Watson et al., 2016a). When patients experienced this caring surrounding, patients reported decreased anxiety, increased preparedness, and hope for a positive care trajectory (Baliski et al., 2014).

DISCUSSION

The findings of this review illustrate that key role domains of ONNs include 1) Care coordinator, 2) Agent of change, and 3) Supporter of patients’ wellbeing. The predominant role domain of an individual ONN varied depending on organizational factors, the care team, and patients’ needs. The ONN promoted care coordination through dissemination of information and the use of presence across the care trajectory. They also acted as a change agent in the clinical setting through enhancing patients’ health literacy, communicating and partnering with stakeholders, and redeveloping trust with patients. The ONN supported the wellbeing of cancer populations by attending to patient’s emotional needs, understanding the interdependency of needs, and transforming the context of care.

Two of the role domains identified in this review, care coordinator and supporter of wellbeing, aligned with Fillion et al.’s (2012a) bidimensional framework. Fillion et al.’s (2012a) dimension of care coordinator, similarly to the care coordinator role in our review, included providing information, managing needs, and promoting therapeutic relationships. Their second dimension, empowerment, focused on supporting coping, self-v, and social supports for patients (Fillion et al., 2012; Pedersen & Hack, 2011) and features similarities with the third role domain in this review (supporter of wellbeing).

Review findings are also consistent with Pedersen and Hack’s (2011) nursing-based approach to the British Columbia Patient Navigation model where navigators promote patients’ problem-solving and active coping strategies to support their wellbeing. This is reflected in the third role domain (supporter of wellbeing) identified in this review. The care coordinator role domain aligns with Pedersen and Hack’s (2011) focus on informational support, access to community supports, and linkage of health care resources. The agent of change domain draws similarities to Pedersen and Hack’s (2011) focus on individual decision making. However, this domain expands upon Pedersen and Hack’s (2011) work to highlight the broadened scope of the ONN in initiating organizational and system wide changes tailored to their patients’ needs.

The majority of included articles examined extensively the two role domains of care coordinator and supporter of wellbeing. Loiselle et al. (2020) identified four functions of the nurse pivot (navigator) including, assessor of needs, provider of information, supporter, and coordinator of care. While descriptions of the key competencies of the ONN differed across Canadian programs and frameworks, all closely aligned with this review’s role domains of care coordinator and supporter of wellbeing.

However, as cancer care in Canada becomes more complex, so too has the ONN’s roles evolved to ensure navigators have the knowledge, skills and competencies to respond to the multidimensional needs of cancer patients and care organizations. This expansion to the role has been recognized in frameworks developed outside of Canada, such as the Oncology Nursing Society’s “Core Competencies of the Oncology Nurse Navigator”, capturing the work of the navigator across two domains, the patient and the system, including roles focused on enhancing coordination in care, giving tailored communication, team-based education, and developing as a professional and an expert ONN (Baileys et al., 2018).

Based on our review findings, existing frameworks (Fillion et al., 2011a; Pedersen & Hack, 2011) on the ONN’s roles in Canada may not fully capture the dynamic, collective-oriented functions of ONNs as depicted in the second domain of change agent, such as translator of knowledge, promoter of self-management, and influencer to eliminate barriers in care. Additionally, previous frameworks outlining the navigator’s responsibilities within the role domains of care coordinator and supporter of wellbeing do not seem to integrate the adaptive (e.g., transformer versus transferer of information) and leadership-focused aspects of navigation (Fillion et al. 2011).

Existing frameworks and those in development in Canada can be revised to recognize the expanding work that ONNs are increasingly assuming. To delineate these complex responsibilities, researchers may be guided by Fitch’s (2008) supportive care framework on cancer patients’ holistic and evolving care needs. This framework has provided a significant foundation for the development of nurse navigation in Canada and deserves the attention of oncology nursing researchers (Fillion et al., 2012b). Future studies on the ONN can also further illuminate the vital role of change agent and investigate the impacts of the ONN on diverse patients’ experiences, an area of interest missing within the literature base in Canada.

In countries outside of Canada, nurse navigation has shown to be an effective approach in reducing cancer disparities and improving satisfaction in care with disadvantaged and underserved communities (Freund et al., 2008; Madore et al., 2014; Rodday et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2022). These developments are a call to expand our research to examine how ONNs contribute to remove barriers in access to cancer care and alleviate cancer disparities affecting underserved populations, a recognized Canadian priority (CPAC, 2019). There is also a need to investigate ONNs’ perspectives on how they contribute to reduce inequities in cancer care and improve patient experience.

Limitations

As per the scope of our review, we only included studies published in English post-2006, excluding articles that would have provided a historical overview of the ONN role. Although we developed a comprehensive search strategy, the search terms may have limited the results. To address this, we examined the reference lists of included articles and outside resources to expand the data set. As the review included primarily studies in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia, the results of this review may not be generalizable to all Canadian provinces and territories.

CLOSING REMARKS

This review has served to further delineate the role of the ONN in Canada, building on previous work on the scope of ONNs’ role in other countries (Baileys et al., 2018). Review findings may assist program developers and decision-makers in determining outcomes and indicators for program evaluation. Review findings may additionally assist individual ONNs in setting their priorities and outlining their distinctive role as they provide care to diverse populations throughout the cancer care continuum (CPAC, 2019).

Appendix A.

Search Strings

(nurs* adj3 (navigat* or coordinat*)).mp.

(oncology or cancer* or neoplasm*).mp.

(Canada or Canadian* or Alberta* or “British Columbia*” or Manitoba* or Ontario* or Saskatchewan or “New Brunswick” or “Nova Scotia*” or “Prince Edward Island” or Newfoundland or quebec* or Yukon or Nunavut or “Northwest Territories”).mp.

Appendix B.

Diagram of the Three Role Domains

REFERENCES

- Ahmed S, Shahid R, Episkenew J. Disparity in cancer prevention and screening in aboriginal populations: Recommendations for action. Current Oncology. 2015;22(6):417–426. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baileys K, McMullen L, Lubejko B, Christensen D, Haylock P, Rose Traudi, Sellers J, Srdanovic D. Nurse navigator core competencies: An update to reflect the evolution of the role. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2018;22(3):272–281. doi: 10.1188/18.CJON.272-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliski C, McGahan C, Liberto C, Broughton S, Ellard S, Taylor M, Bates J, Lai A. Influence of nurse navigation on wait times for breast cancer care in a Canadian regional cancer center. The American Journal of Surgery. 2014;207:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beben N, Muirhead A. Improving cancer control in First Nations, Inuit, and Metis communities in Canada. English Journal of Cancer Care. 2016;25(2):219–221. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais D. Nurse navigation: Supporting patients and their families through the health care system. Alberta Nurse. 2008;64(7):19–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais M, St. Hilaire A, Fillion L, Serres M, Tremblay A. What to do with screening for distress scores? Integrating descriptive data into clinical practice. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2014;12:25–38. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome S. Integrative literature reviews for the development of concepts. In: Rogers B, Knafl K, editors. Concept development in nursing. Philadelphia: Saunders Co; 1993. pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Budde H, Williams G, Scarpetti G, Kroezen M, Maier C. What are patient navigators and how can they improve integration in care? 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK577643/ [PubMed]

- Campbell C. An oral cancer therapy nurse navigator role. Canadian Nurse. 2016;112(3):26–28. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology. Patient navigator in cancer care: A specialized oncology nurse role that contributes to high quality, person-centred care experiences and clinical efficiencies. 2020. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cano-acio.ca/resource/resmgr/position_statements/Patient_Navigation_2020_EN.pdf . [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Canadian Cancer Society. Canadian cancer statistics. 2021. https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2021-statistics/2021-pdf-en-final.pdf .

- Canadian Cancer Society. Canadian cancer statistics: A 2022 special report on cancer prevalence. 2022. https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2022-statistics/2022-special-report/2022_prevalence_report_final_en.pdf .

- Canadian Cancer Society. Cancer statistics at a glance. 2022. https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics/cancer-statistics-at-a-glance .

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. 2019–2029 Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control. cancerstrategy.ca 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Lung cancer and equity: A focus on income and geography. 2020. https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Lung-cancer-and-equity-report-EN.pdf .

- Cha J, McKevitt E, Pao J, Dingee C, Bazzarelli A, Warburton R. Access to surgery following centralization of breast cancer surgical consultations. The American Journal of Surgery. 2020;219:831–835. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Common J, Mariathas H, Parsons K, Greenland J, Harris S, Bhatia R, Byrne S. Reducing wait time for lung cancer diagnosis and treatment: Impact of a multidisciplinary, centralized referral program. Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal. 2018;69:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook S, Fillion L, Fitch M, Veillette A, Matheson T, Aubin M, Serres M, Doll R, Rainville R. Core areas of practice and associated competencies for nurses working as professional cancer navigators. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2013;23(1):44–62. doi: 10.5737/1181912x2314452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J, Brudnoy L, Soong T, Graham T. Patient navigation in oncology nursing: An innovative blended learning model. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2013;44(10):461–470. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20130903-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie K, Strohschein F, Loiselle C. Living with cancer and other chronic conditions: Patients’ perceptions of their healthcare experience. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2017;27(1):43–47. doi: 10.5737/236880762714348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchegary H, Pike A, Puddester R, Watkins K, Warren M, Francis V, Woods M, Green J, Savas S, Seal M, Gao Z, Avery S, Curtis F, McGrath J, MacDonald D, Burry N, Dawson L. Cancer prevention in cancer predisposition syndromes: A protocol for testing the feasibility of building a hereditary cancer research registry and nurse navigator follow up model. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion L, de Serres M, Lapointe-Goupil R, Bairati I, Gagnon P, Deschamps M, Savard J, Meyer F, Belanger L, Demers G. Implementing the role of patient navigator nurse at a university hospital centre. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2006;16(1):11–17. doi: 10.5737/1181912x1611117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion L, Aubin M, Serres M, Robitaille D, Veillette A, Rainville F. The process of integrating oncology nurse navigators into joint (hospital-community) local teams. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2010;29(1):30–35. doi: 10.5737/1181912x201E29E34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion L, Cook S, Blais M, Veillette A, Aubin M, Serres M, Rainville F, Fitch M, Doll R, Simard S, Fournier B. Implementation of screening for distress with professional cancer navigators. Oncologie. 2011;13:277–289. doi: 10.1007/s10269-011-2026-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion L, Cook S, Veillette A, Aubin M, de Serres M, Rainville F, Fitch M, Doll R. Professional navigation framework: Elaboration and validation in a Canadian context. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2012a;39(1):58–70. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E58-E69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion L, Cook S, Veillette A, de Serres M, Aubin M, Rainville F, Fitch M, Doll R. Professional navigation: A comparative study of two Canadian models. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2012b;22(4):257–266. doi: 10.5737/1181912x224257266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch M. Supportive care framework. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2008;18(1):6–14. doi: 10.5737/1181912x181614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H, Rodriguez R. The history and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(15):3539–3542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, Dudley DJ, Fiscella K, Paskett E, Raich PC, Roetzheim RG. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3391–3399. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert J, Green E, Lankshear S, Hughes E, Burkoski V, Sawka C. Nurses as patient navigators in cancer diagnosis: Review, consultation, and model design. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2010;20:228–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Given B, Given C, Sikorskii A, Vachon E, Banik A. Medication burden of treatment using oral cancer medications. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2017;4(4):275–282. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_7_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase K, Anderson J, Knox A, Skrutkowski M, Snow B, Moody L, Pool Z, Vimy K, Watson L. Development of a national position statement on cancer patient navigation in Canada. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2020;30(2):73–92. doi: 10.5737/236880763027382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert J, Fillion L. Gaining a better understanding of the support function of oncology nurse navigators from their own perspective and that of people living with cancer: Part 1. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2011a;21(11):33–38. doi: 10.5737/1181912x2113338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, Fillion L. Gaining a better understanding for the support function of oncology nurse navigators from their own perspective and that of people living with cancer: Part 2. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2011b;21(1):33–38. doi: 10.5737/1181912x2113338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyathevan G, Lemonde M, Cooper A. The role of oncology nurse navigators in enhancing patient empowerment within the diagnostic phase for adult patients with lung cancer. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2017;27(2):164–170. doi: 10.5737/23688076272164170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammili A, Morency D, Cools-Lartigue J, Ferri L, Mueller C. Remoteness from urban centre does not affect gastric cancer outcomes with established care pathway to specialist centre. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2021;66(3):219–227. doi: 10.1503/cjs.019420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmarov I, Ferrante A. The development of anti-cancer programs in Canada for the geriatric population: An integrated nursing and medical approach. The Aging Male. 2011;14(1):4–9. doi: 10.3109/13685538.2010.524954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie J, Kaufert J, Browne A, O’Neil J. Managing Matajoosh: Determinants of first Nations’ cancer care decisions. BMC Health Services Research. 2016;16(402):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1665-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiselle C, Attieh S, Cook E, Tardiff L, Allard M, Rousseau C, Thomas D, Saha-Chaudhuri P, Talbot D. The nurse pivot navigator associated with more positive cancer care experiences and higher patient satisfaction. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2020;30(1):48–60. doi: 10.5737/236880763014853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madore S, Kilbourn K, Valverde P, Borrayo E, Raich P. Feasibility of a psychosocial and patient navigation intervention to improve access to treatment among underserved breast cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22(8):2085–2093. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand P. The clinical nurse specialist as nurse navigator: Ordinary role presents extraordinary experience. Canadian Oncology Nursing Research. 2010;20(2):80–83. doi: 10.5737/1181912x2028083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem D, Daneault S. Needs of cancer patients in palliative care during medical visits. Canadian Family Physician. 2017;63:536–542. doi: 10.5737/1181912x2028082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Urquhart R, Kephart G, Asarda Y, Younis T. Nurse navigators’ views on patient and system factors associated with navigation needs among women with breast cancer. Current Oncology. 2021;28:2107–2114. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28030195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park G, Johnston G, Urquhart R, Walsh G, McCallum M. Comparing enrolees with non-enrolees of cancer-patient navigation at end of life. Current Oncology. 2018;25(3):184–192. doi: 10.3747/co.25.3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A, Hack T. The British Columbia patient navigation model: A critical analysis. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38(2):200–206. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.200-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A, Hack T, McClement S, Taylor-Brown J. An exploration of the patient navigator role; perspectives of younger women with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2014;41(1):77–88. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.77-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante A, Joannette S. Integrating nurse navigators in Monteregie’s oncology teams: One aspect of implementing the cancer control program: Part 1. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2009a;19(1):13–18. doi: 10.5737/1181912x191P1P6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante A, Joannette S. Integrating nurse navigators in Monteregie’s oncology teams: The process. Part 2. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2009b:72–77. doi: 10.5737/1181912x1927277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard M, Parmar M, Calestagne P, McVey L. Seeking patient feedback: An important dimension of quality in cancer care. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2010;25(4):344–351. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3181d5c055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritvo P, Myers R, Paszat L, Tinmouth J, McColeman J, Mitchell B, Serenity M, Rabeneck L. Personal navigation increases colorectal cancer screening uptake. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention. 2015;24(3):506–511. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Barton G, McDonald A. Supporting First Nations, Inuit, and Metis (FNIM) in an oncology setting-My experience as a FNIM nurse navigator. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2020;30(4):300–303. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodday AM, Parsons SK, Snyder F, Simon MA, Llanos AA, Warren-Mears V, Dudley D, Lee JH, Patierno SR, Markossian TW, Sanders M, Whitley EM, Freund KM. Impact of patient navigation in eliminating economic disparities in cancer care. Cancer. 2015;121(22):4025–4034. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanthan A, Amir E, Warner E. Does a dedicated program for young breast cancer patients affect the likelihood of fertility preservation discussion and referral? The Breast. 2016;27:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S, Truant T. Will designated patient navigators fix the problem? Oncology nursing in transition. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2010;20(3):1–6. doi: 10.5737/1181912x192P1P6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevillion K, Singh-Carlson S, Wong F, Sherriff C. An evaluation report of the nurse navigator services for the breast cancer support program. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2015;25(4):409–414. doi: 10.5737/23688076254409414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C, Zimmerman C, Barrero C, Kalmar C, Butler P, Guevara J, Bartlett S, Taylor J, Folsom N, Swanson J. Reduced socioeconomic disparities in cleft care after implementing a cleft nurse navigator program. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 2021;59(3):320–329. doi: 10.1177/10556656211005646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson L, Anderson J, Champ S, Vimy K, Delure A. Developing a provincial cancer patient navigation program utilizing a quality improvement approach part 2: Developing a navigation education framework. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2016a;26(3):186–193. doi: 10.5737/23688076263186193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson L, Anderson J, Champ S, Vimy K, Delure A. Developing a provincial cancer patient navigation program utilizing a quality improvement approach part three: Evaluation and outcomes. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2016b;26(2):122–128. doi: 10.5737/236880762631861931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Nielson D, Dayao Z, Brown-Glaberman U, Tawfik B. Patient-reported measures of a breast cancer nurse navigator program in an underserved, rural, and economically disadvantaged patient population. Oncology Nursing Society. 2022;49(6):532–539. doi: 10.1188/22.ONF.532-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibrik K, Laskin J, Ho C. Implementation of a lung cancer nurse navigator enhances patient care and delivery of systemic therapy at the British Columbia Cancer Agency, Vancouver. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2016;12(3):344–349. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.008813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]