Abstract

Background:

A case of chronic osteomyelitis with Brodie’s abscess of the cuboid caused by a wooden foreign body penetrating the plantar foot. Total cuboidectomy was carried out with implantation of an anatomically molded antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer with culture-specific postoperative intravenous antibiotics. At six months of follow-up, the patient was completely asymptomatic without evidence of a recurrence of infection. Final radiographs also didn’t show spacer migration or surrounding bone erosions. The spacer obviated the need for any foot fusion which preserved foot biomechanics. The patient didn’t need to use any braces or insoles.

Conclusion:

Osteomyelitis should always be on the differential list of lytic lesions of the tarsal bones, especially if there is a history of prior foot trauma. In this case, cuboid excision and placement of an antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer provided sustained relief of symptoms without evidence of recurrence or complications for six months.

Level of Evidence: V

Keywords: cuboid osteomyelitis, brodie’s abscess, total cuboidectomy, cement spacer

Introduction

The foot is susceptible to penetrating injuries that carry a significant risk of retained foreign bodies, particularly if not adequately addressed.1,2 The behavior of a retained foreign body may vary depending on several factors, including but not limited to the object's characteristics, level of contamination, location of the object's final seeding location, local blood supply, host immunity, and the quality and timing of treatment.3,4 The condition has the potential to be in a quiescent state for variable period of time which adds to the variations in the clinical presentation and the complexity of the management.2,5-7 Broadly, diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion, especially in chronic and sub-acute cases with an unclear or remote history of penetrating injury.8 The aim of this study was to report the management of a case of cuboid osteomyelitis due to retained foreign body three years after a penetrating foot injury.

Case Report

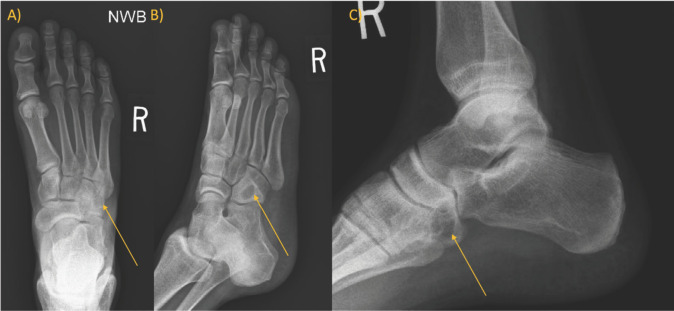

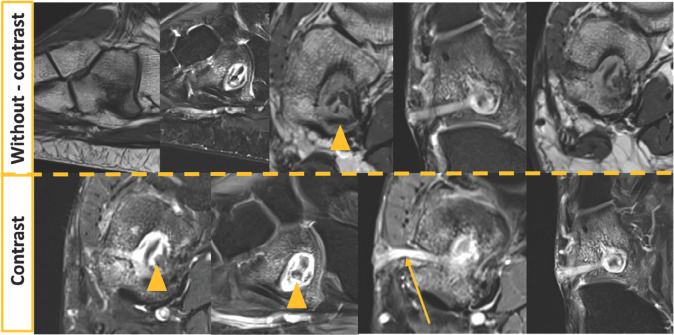

A 36-year-old male presented to our clinic with the chief complaint of a chronic lateral draining wound over the lateral aspect of his right midfoot for the last three years. He stated he was intoxicated, walking throughout the woods while hunting when he stepped on a sharp tree branch that penetrated his boot into his foot. Subsequently, he was treated with a series of operative debridement with removal of foreign bodies from his foot in an outside facility. After healing of his surgical wounds, he continued to have chronic draining sinuses over the lateral midfoot. He denied any history of recent fever, chills, or redness at the time of his presentation to our clinic. He only noticed episodic flares of pain over the cuboid with increased drainage. He was on oral cephalexin, acetaminophen, or ibuprofen as needed. He had a normal complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) at time of presentation. Pre-operative radiographs showed a lytic lesion of the cuboid measuring 16.3 x 9.9 mm (Figure 1). The lesion was calculated on MRI to be 14 x 12 x 14 mm. The draining sinus originated from the cuboid. The possibility of bony sequestrum or foreign body in the cavity of the lesion was noted. (Figure 2)

Figure 1A to 1C.

Pre-operative radiographs: oval lytic lesion in the cuboid surrounded by a relatively thick and dense reactive bony sclerosis.

Figure 2.

Pre-operative MRI imaging: The upper row shows images without contrast material, the lesion measured around 1.4 x 1.2 x 1.4 cm, it showed hypointense signal on T1 sequence and hyperintense signal on T2 with small central islands of hypodense lesions on both T1 and T2 suggesting sequestrum (arrow heads). The bottom row portrays images after contrast, there was hyperintense T2 signal with post-contrast enhancement except for the central small islands of sequestrum (arrow heads). There was a sinus track lesion extending from the central cavity to the plantar lateral skin (arrow).

Surgical Procedure

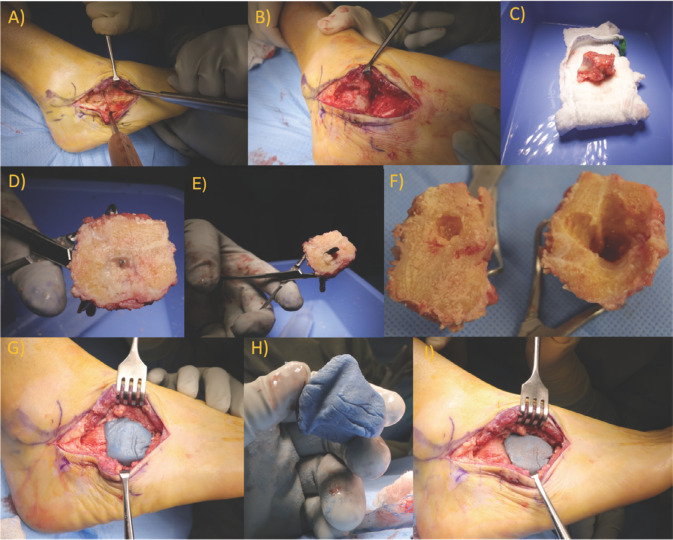

The procedure was performed under general anaethesia. The right lower limb was exsanguinated by elevation for three minutes, then a thigh tourniquet was inflated. A standard lateral approach was carried out starting from the fibular tip to the fourth metatarsal base with care to avoid injury the superficial peroneal nerve and the sural nerve branches. Using bipolar cautery, the incision was carefully deepened. The extensor digitorum brevis (EDB) was reflected from the dorsal aspect of the calcaneus bone, and the peroneal tendons were retracted inferiorly. The cavity was 2 mm distal to the cuboid subchondral at the calcaneocuboid joint. Debridement of the cavity with a satisfactory safe margin of at least 5 mm didn’t seem to be applicable without compromising the integrity of the subchondral bone at the calcaneo-cuboid joint. The decision was made to remove the cuboid en bloc in order to obtain clear margins. The cuboid was carefully freed from the attached ligaments by sharp dissection. Using a Cushing elevator, the cuboid was mobilized and the peroneus longus was preserved. No purulence was noted around the cuboid in all aspects, and the cuboid looked structurally intact except for the sinus tract. Copious irrigation using low-pressure pulse lavage was done, and the sinus track in the skin was traced and removed. On the back table, the cuboid was transected coronally using a power saw at the top of the cavity. In the cut section, the cuboid walls were sclerotic around a cavity that contained a piece of wood, which was sent for culture. (Figure 3) The cavity bone and associated soft tissue reaction were biopsied and sent for cultures and histopathological evaluation. A package of cobalt cement was mixed with antibiotic powder (vancomycin and tobramycin). The mixture was carefully molded into the shape of the explanted cuboid and sequentially reduced in the cuboid bed for trimming the shape and size of the cement spacer, preserving normal relationships with the surrounding bone and joint surfaces, and maintaining the groove for the peroneus longus tendon on the plantar surface. (Figure 3) The final mold of the cuboid spacer was made when the foot was placed in a slightly everted position to allow for some space to accommodate normal foot pronation during a foot flat stance. The cuboid spacer was then removed to harden outside of the foot and avoid thermal burns during the peak of the exothermic reaction.

Figure 3A to 3I.

(3A) Lateral approach for the hindfoot; the arrow indicates the potential aperture of the cavity. (3B, 3C) Complete en block removal of the cuboid bone. (3D to 3F) Cut-section of the cuboid showing the wooden foreign body and the surrounding sclerosed walls. (3G) Molding of the cuboid cement spacer. (3H) Cuboid cement spacer with molded groove for peroneus longus tendon. (3I) Final implantation of the cuboid spacer.

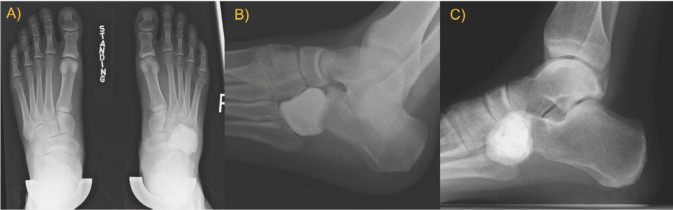

After the spacer was implanted it was stable throughout range of motion with no need for any additional fixation. Layered closure was then performed, and a standard below-knee AO splint was applied for three weeks. Histopathological examination confirmed the intra-operative findings: organic foreign body material was surrounded by granulation tissue, while the cuboid showed evidence of chronic osteomyelitis. Cultures returned positive for Ochrobactrum intermedium and Clostridium sphenoides. According to the recommendations of a musculoskeletal infectious disease specialist, metronidazole was prescribed for three weeks postoperatively. The patient was partial weight-bearing until the incision was fully healed then sutures were removed (three weeks postoperatively). Progressive weight bearing was allowed after suture removal. The patient reported significant improvement in pain and complete resolution of the sinus without any evidence of inflammation around the injury area. At six months follow-up, the patient presented with complete resolution of any pain and tenderness in the foot. He was also able to walk without any difficulties, assistive devices, or orthotics. Six-month follow-up conventional weight-bearing radiographs showed an anatomically shaped spacer with stable alignment. Foot alignment was maintained as evidenced by a symmetric lateral column length as well as unchanged forefoot and midfoot alignment. (Figure 4)

Figure 4A to 4C.

Six-month follow-up weight bearing radiographs: Complete excision of the cuboid with replacement of anatomically contoured and stable cement spacer in place. Proper foot alignment of was noted in both weightbearing antero-posterior and lateral radiographs (4A and 4C, respectively).

Discussion

The current study reports a novel treatment for a rare pathology of cuboid osteomyelitis caused be a foreign body following penetrating foot injury. Complete excision of the cuboid was necessary in this case to achieve full eradication of the infection in a single stage. The antibiotic- impregnated cement spacer managed to maintain foot alignment without evidence of complications such as wound healing problems, loosening, or surrounding bone resorption. There are a few reports on cuboid Brodie’s abscess. To the best of our knowledge, there was only one adult case, and a few repots in the pediatric population. Tarsal bone Lytic lesions have a wide spectrum of differential diagnosis such as Brodie’s abscess, osteoid osteoma, non-ossifying fibroma, giant cell tumor, eosinophilic granuloma, chondroblastoma, and unicameral bone cyst. Foreign body should be included in the differential especially if there is a history of prior penetrating foot injury.8

Bagatur et al. reported a Brodie’s abscess in a 28-year-old woman cuboid without a prior history of trauma. The case diagnosis was delayed for approximately three months. All laboratory markers were reported within normal range; however, radiographs showed a radiolucent lesion of the cuboid, while MRI suggested a Brodie’s abscess in the cuboid (2 x 1.5 cm). The patient underwent surgical debridement, which revealed a cavity filled with pus and surrounded by sclerotic bone.9 At six-year follow-up, the authors reported no residual symptoms and normal radiographs.9

In the pediatric populations, Agarwal et al. reported a cuboid Brodie’s abscess in a ten-year-old boy after a penetrating thorn prick injury.1 The patient was treated with surgical debridement in addition to broad-spectrum post-operative antibiotics. A cortical window was made in the cuboid, and the cavity contents were evacuated without evidence of a foreign body. Interestingly, the culture returned negative for any microorganisms.1 The patient was followed up only for six weeks, and he had complete resolution of symptoms at the last visit.1 Amit et al. reported another case of Brodie’s abscess in a 14-year-old child after a penetrating iron nail. The patient presented two months after the incident with pain and swelling over the cuboid. He was afebrile and had normal inflammatory markers except for ESR (36 mm/hour). Radiographs revealed the typical lucent lesion surrounded by cortical sclerosis.2 The cultures grew Streptococcus pyogens. The patient was treated operatively with surgical debridement and post-operative antibiotics for six weeks. The patient was followed up for nine months without evidence of recurrence.2

Anatomic cement spacers are not novel in adult foot and ankle surgical reconstruction.10,11 They have been used with good results in the treatment of infected ankle replacements or after a significant bone loss.10,11 However, the spacers are usually employed as a bridging procedure for the definitive treatment. In a retrospective series of nine patients, Ferrao et al. presented the results of cement spacers as a definitive treatment after failed total ankle replacement or fusion.12 They reported that seven patients (77.78%) retained the spacer for a 20.1 month average (range: 6–62 months).12 Radiographic evaluation revealed that two patients had loosening and migrations of the spacer; However, interestingly, no erosion, resorption, neighboring bone loss were reported. They suggested this strategy as a valid treatment option for patients who are asymptomatic with good functionality after the spacer implantation or who are too ill to go for another reconstructive surgery.12

There are a few long-term reports of cement spacers after total knee or hip replacement.13,14 Regis et al. reported a satisfactory outcome of a permanent spacer after an infected knee replacement at six year follow-up with sufficient preservation of the bone stock.13 Durbhakula et al. reported that two patients (who were medically unfit for a second stage reconstruction) were walking with an assistive device and experiencing minimal pain at a five-year follow-up after a spacer endoprosthesis surgery for infected total hip arthroplasty.14 Scharfenburger et al. presented a series of 16 patients who had retained cement spacers after infected total hip arthroplasty. They reported that all the patients were doing well in terms of function and pain. Ten patients were not medically fit for a second surgery, and six patients refused revision surgery since they were satisfied with the outcome of the spacer.15

Our rationale behind this line of surgical treatment plan was to ensure full infection eradication in one stage, in addition to maintaining the integrity of the surrounding joints as well as the lateral column length. In retrospect, we believe this strategy was the best option for the patient given the culture results, which showed an atypical organism (potentially having sub-optimal results with typical antibiotics), chronicity of the condition (approximately three years), chronic osteomyelitis of the cuboid bone on histopathologic examination, and proximity of the cyst to the calcaneocuboid joint. We elected to proceed with a cement spacer mixed with broad-spectrum antibiotics to deliver a high concentration of local antibiotics with minimal systemic side effects.16,17 Our team reached a shared decision with the patient that the spacer could serve as a definitive management as long as he remained asymptomatic. We discussed clinical complication that could occur such as skin problems, difficulty walking, or local tenderness, or radiographic complications such as migration, spacer loosening, or resorption of the surrounding bone. We discussed if it seemed appropriated to replace the spacer in the future with a three-dimensional (3D) printed total cuboid.18

In conclusion, penetrating foot injuries carry a risk of sub-acute presentation of osteomyelitis in tarsal bones. In this case, excision of the cuboid was required to eradicate the infection. Preservation of hindfoot mechanics and mobility was obtained by using an anatomic cement spacer to replace the excised cuboid. This technique and the potential for future 3D printed bone implants can help to avoid motion limiting arthrodesis especially in younger patients like this.

References

- 1.Agarwal S, Akhtar MN, Bareh J. Brodie’s abscess of the cuboid in a pediatric male. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery. 2012;51(2):258–61. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2011.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amit P, Maharajan K, Varma B. Streptococcus pyogenes associated post-traumatic Brodie’s abscess of cuboid: A case report and review of literature. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports. 2015;5(3):84. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassan FOA. Retained toothpick causing pseudotumor of the first metatarsal: a case report and literature review. Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2008;14(1):32–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MAYLAHN DJ. Thorn-induced" tumors" of bone. JBJS. 1952;34(2):386–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller EH, Semian D. Gram-negative osteomyelitis following puncture wounds of the foot. JBJS. 1975;57(4):535–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth S, Zaninovic M, Roth A. Sponge rubber revealed two years after penetrating injury: a case report. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2017;56(4):885–8. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Y-M, Yang S-W, Chen C-Y, Hsu C-J, Chang W-N. Residual foreign body in the foot causing chronic osteomyelitis mimicking a pseudotumor: A case report. Journal of International Medical Research. 2020;48(6):0300060520925379. doi: 10.1177/0300060520925379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimose S, Sugita T, Kubo T, Matsuo T, Nobuto H, Ochi M. Differential diagnosis between osteomyelitis and bone tumors. Acta Radiologica. 2008;49(8):928–33. doi: 10.1080/02841850802241809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagatur AE, Zorer G. Brodie's abscess of the cuboid bone: a case report. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (1976-2007) 2003;408:292–4. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200303000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang P, Lundgren ME, Garapati R. Complete talar extrusion treated with an antibiotic cement spacer and staged femoral head allograft. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018;26(15):e324–e8. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patton D, Kiewiet N, Brage M. Infected total ankle arthroplasty: risk factors and treatment options. Foot & ankle international. 2015;36(6):626–34. doi: 10.1177/1071100714568869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrao P, Myerson MS, Schuberth JM, McCourt MJ. Cement spacer as definitive management for postoperative ankle infection. Foot & Ankle International. 2012;33(3):173–8. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regis D, Sandri A, Magnan B, Bartolozzi P. Six-year follow-up of a preformed spacer for the management of chronically infected total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:1111–5. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durbhakula SM, Czajka J, Fuchs MD, Uhl RL. Spacer endoprosthesis for the treatment of infected total hip arthroplasty. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2004;19(6):760–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scharfenberger A, Clark M, Lavoie G, O'Connor G, Masson E, Beaupre L. Treatment of an infected total hip replacement with the PROSTALAC system: part 1: infection resolution. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2007;50(1):24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchholz H, Elson R, Heinert K. Antibiotic-loaded acrylic cement: current concepts. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1984(190):96–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens CM, Tetsworth KD, Calhoun JH, Mader JT. An articulated antibiotic spacer used for infected total knee arthroplasty: a comparative in vitro elution study of Simplex® and Palacos® bone cements. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2005;23(1):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadakia RJ, Akoh CC, Chen J, Sharma A, Parekh SG. 3D printed total talus replacement for avascular necrosis of the talus. Foot & Ankle International. 2020;41(12):1529–36. doi: 10.1177/1071100720948461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]