Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine facilitators of behavior change and weight loss among African-American women who participated in the Moving Forward Efficacy trial.

Methods

Linear mixed models were used to examine the role of self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety on weight, physical activity, and diet. We also examined the mediation of self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety on weight loss, physical activity, and diet using the Freedman Schatzkin statistic.

Results

We found no evidence to suggest mediation, but some direct associations of self-efficacy, certain types of social support and perceived access to exercise on weight loss, and behavior change.

Conclusion

We determined that self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to exercise played a role in weight loss, increased MVPA, and better diet. The role of self-efficacy and perceived access to exercise were more consistent than social support.

Keywords: Weight loss, Breast cancer, African American breast cancer survivors

Introduction

In the USA, breast cancer survival rates are substantially lower for African-American (AA) women versus White women (WW). While 92% of WW survive 5 years after diagnosis, only 83% of AA women survive [1]. Disparities in survival rates are attributed to a myriad of social [2, 3] and individual factors [4], with obesity being one [5]. Obese women have an alarming rate of 33% increased risk of mortality relative to normal weight women with breast cancer [6]. AA women are disproportionately burdened with overweight and obesity when diagnosed with breast cancer and gain twice as much weight as WW in the years after diagnosis [5]. Given the impact of overweight and obesity on increased cancer and all-cause mortality, interventions focused on losing weight and behavior change may increase breast cancer survival [7], particularly among AA women.

In a recent review on health behavior and weight loss interventions among AA Breast Cancer Survivors (AABCS), Paxton et al. concluded that AABCS adhere to health behavior and weight loss interventions and make modest to significant changes [8], however, more research is needed to examine facilitators of weight loss and behavior change [9, 10]. In this study, we examine the direct and mediating effect of five facilitators (i.e., self-efficacy, social support and perceptions of environment, namely perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety) on behavior change and weight loss in Moving Forward (MF), a large weight loss efficacy trial with AABCS [11-13]. The Moving Forward intervention is grounded in social cognitive theory within a socioecological framework and addresses self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise resources and neighborhood safety as important factors associated with successful weight loss and related behavior change.

Interventions among non-cancer affected populations widely target theory-driven constructs, like self-efficacy [14], and other concepts such as social support [15], to successfully facilitate behavior change and weight loss. Although few interventions with AABCS have examined self-efficacy and social support [10, 12, 13, 16], improvements in self-efficacy and social support have led to positive health changes among samples of predominately White survivors of breast and other cancers [16]. In these interventions, higher self-efficacy was associated with increases in physical activity (PA) and/or better diet, which over time can lead to weight loss. Further, a systematic review of behavioral interventions among breast and other adult cancer survivors, found a significant relationship between improved social support and increased PA, particularly among breast cancer survivors [16]. Similarly, a review of weight loss interventions among cancer survivors found social support, goal setting, action planning, and instruction on how to perform the behavior were associated with intervention effectiveness [17]. Specifically among AABCS, several studies acknowledge the value of social support in behavioral interventions (e.g., diet, physical activity) but do not report on changes or associations with outcomes [12, 18-20].

Studies among non-cancer affected AA women have examined the role of social support and weight loss and associated behaviors and report inconsistent findings. Some studies report social support is an important component of weight loss in initiating and maintaining weight loss behaviors [21-23], while others document no association between social support and weight loss among AA women [24]. These mixed findings warrant further investigation into the contributing role of self-efficacy and social support in behavior change and weight loss among AABCS. Additionally, exploring the influence of perceived environmental access and barriers is relevant given AA women are disproportionately more likely to reside in urban environments that contribute to obesity and weight gain [25-27].

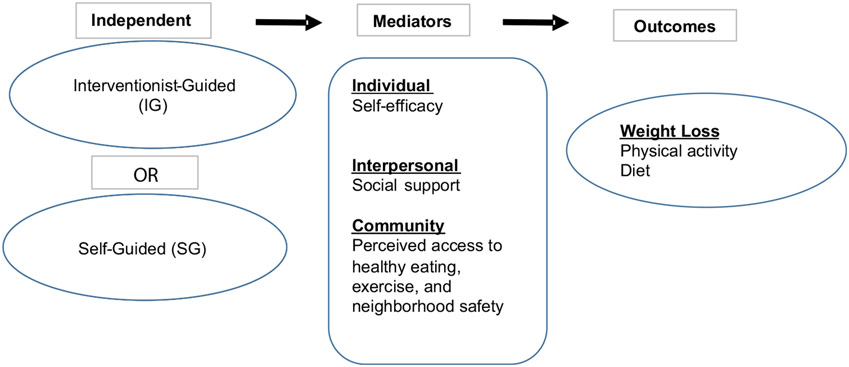

This paper seeks to understand how self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise resources and neighborhood safety changed over the course of the Moving Forward Weight Loss Intervention and if these factors facilitated changes in weight loss, and behavior (i.e., PA, and diet) among AABCS (see Fig. 1). We examined associations with these five facilitators (i.e., self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety) on weight loss, physical activity, and diet in separate models: (1) the role of changes in self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety over time, and (2) the mediating effects of self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety.

Fig. 1.

Moving Forward conceptual model

Methods: Study Design

Moving Forward was a community-based, randomized, weight loss intervention trial with 246 overweight/obese AABCS. Survivors were recruited between September 2011 and September 2014 through direct contact by letter and phone using hospital cancer registry information from three Chicago-area academic cancer centers. Community-based efforts, including referrals from oncologists, flyers, social media, and presentations were also used [28]. The study was based in eight Chicago Park District (CPD) facilities located within predominately AA communities.

Eligible participants were AABCS (stages I–III), ≥ 18 years of age, a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2, completed cancer treatment at least 6 months before recruitment (hormonal therapy allowed), physically able to participate in moderate physical activity per health-care provider approval, and agreeable to study procedures. Women were excluded if they were pregnant or planning to become pregnant during the study, taking prescription weight loss medication, or planning weight loss surgery in the coming year. The respective institutional review boards approved all study procedures, and each participant provided written informed consent. Women were randomly assigned to either the 6-month Interventionist-Guided group (IG) or the Self-Guided group (SG) using a random digit generator after the baseline interview.

Moving Forward study design, protocol, intervention [28], and outcomes [9] were described previously. Goals for both interventions were a 5% weight loss for the 6-month period to be achieved by decreased caloric intake (~ 500 kcal), increased fruit and vegetable consumption, and increased moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (minimum ≥ 150 min per week), in line with American Cancer Society cancer survivor guidelines. Briefly, IG included twice-weekly in-person classes with supervised exercise and twice-weekly text messaging targeting enhanced self-efficacy, social support and access to health promotion resources. Participants in both groups received a program binder with handouts, recipes, and other supportive materials related to behavior change and weight loss. SG participants did not attend classes or receive text messages. At post-intervention, both groups received monthly newsletters reviewing curriculum information, news of local healthy eating and exercise resources, and participant testimonials.

Measures

Demographic data

We collected age (years), education (highest grade completed), and annual household income (categories of combined family income).

Obesity/Overweight

Two measurements for height and weight were taken per participant to estimate mean body mass index (BMI). Height (baseline only) was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Seca). A third measurement was taken for discrepancies of more than 0.5 cm for height or 0.2 kg for weight between measurements. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital scale (Tanita), with participants wearing light clothes without shoes.

Leisure-time activity

MET-hours per week was calculated using the Modified Activity Questionnaire (MAQ) [29] by assessing self-reported average frequency and duration of 17 popular activities (e.g., walking, gardening) performed on at least ten occasions in the last year. Other activities not listed among the popular activities, but were performed on at least ten occasions, were also listed. The MAQ has been used in many large studies with diverse samples, including cancer survivors [30], and has well-established reliability and validity [29].

Dietary intake

Healthy Eating Index (HEI) was calculated by Nutrition-Quest using the interviewer administered Block 2005 Food Frequency Questionnaire, a measure well validated with diverse populations [31, 32]. HEI is a measure developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to assess diet quality [33]. The HEI scores a set of foods based on the amount of variety in the diet, and compliance with specific dietary guidelines and recommendations. Overall score for the HEI ranges from 0 to 100 and is comprised of scores from the 13 components that reflect the key recommendations in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. A higher score represents higher adherence to guidelines.

Breast cancer diagnosis and treatment

Medical record abstraction and self-report questionnaires provided information on breast cancer diagnosis, and treatment.

Physical activity and nutrition self-efficacy

This 11-item instrument [34] assesses the participant’s level of confidence to complete particular activities that promote weight loss. This scale has adequate reliability, internal consistency, and construct validity, as well as good predictive validity among AAs. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 in this sample.

Social support for eating and exercise

The social support questionnaire contains 40 items to assess social support for eating and exercise from family and friends. Each item asks respondents to rate separately for family and friends how often (1 = never, 5 = very often) they have done or said certain things related to the respondents’ efforts to change their dietary or exercise habits during the past 6 months [35]. Social support for eating and exercise has two subscores for eating (encouragement and discouragement) and one subscore for exercise (participation) for the following four subscales: (1) Friend support for healthy eating habits, (2) Family support for healthy eating habits, (3) Friend support for exercise habits, and (4) Family support for exercise habits [35]. Measures for the optional rewards and punishment subscale for family and friend support for exercise habits were not included in our questionnaire because it did not emerge in the factor analysis for friends in the development of the scale by Sallis et al. [35]. Scores are calculated by summing responses of the items that load on each factor. This questionnaire was developed with a predominately white sample; thus, we sought to confirm the scale’s structure for our population using a factor analysis with varimax rotation. Our results confirmed two subscores for eating (encouragement and discouragement) and one for exercise (participation). Internal consistency coefficients ranged from 0.73 to 0.87.

Perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety

To measure perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety we included items from the perceived access to healthy eating and exercise scale from the “Robert Wood Johnson Active Where?” study [44]. Respondents rate their level of agreement (1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree) with five statements related to healthy eating, four statements related to perceived access for exercise, and five statements related to perceived neighborhood safety. Scores were summed across each group of statements to create three separate measures for perceived access to healthy eating, perceived access to exercise, and perceived neighborhood safety. We reverse scored the measures, so that a higher score meant a better perception of the measure. All scales show good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha from 0.78 to 0.94 [44].

Statistical analyses

We report descriptive statistics for all outcomes of interest from baseline to post-intervention, including anthropometric and behavioral outcomes (weight, MVPA, or diet) stratified for IG and SG groups at baseline and post-intervention. We report adjusted differences in the mean using the linear model, as well as estimated standard errors for the adjusted differences. The statistical significance of the difference in outcomes between the IG and SG groups was assessed using t test and chi-square where relevant. Analyses on weight, MVPA, and diet were performed by a linear mixed model accounting for time (i.e., baseline, 6 months, 12 months) and treatment group (i.e., IG or SG), age, income, education, and breast cancer diagnosis. For weight, we analyzed data 654 observations (246 participants for time 1, 210 participants for time 2, and 198 participants for time 3), 84 observations were excluded for participants who were missing weight for time 2 or 3. For MVPA, we analyzed 662 observations (246 participants for time 1, 210 participants for time 2, and 204 participants for time 3), 80 observations were excluded for participants who were missing MVPA for time 2 or 3. For diet, we analyzed 637 observations (221 participants for time 1, 212 for time 2, ad 204 for time 3) 80 observations were excluded for participants who were missing diet at times 1, 2, or 3.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In addition, mediation models were calculated using the Freedman and Schatzkin statistic to test whether self-efficacy, social support, or perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety mediated the association between group and weight loss or MVPA or diet (objective 2).

Results

Two-hundred and forty-six AABCS participated in the study (IG n = 125, SG n = 121) at baseline, 212 participants completed 6-month intervention (IG n = 111, SG n = 101), and 204 participants completed 12 months (IG n = 107, SG n = 100). Descriptive characteristics for the sample are provided in Table 1. Groups were comparable in age, education, income, BMI, and breast cancer diagnosis at baseline. Mean age was 57.5 years, mean weight loss was 2.5 kg, and mean self-reported MVPA was 164.0 min/wk. Participants reflected a broad range of education and income levels.

Table 1.

Characteristics for the African-American breast cancer survivors participating in moving forward: a behavioral weight loss intervention

| Variable | Total (n = 246) n (%) |

Group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IG (n = 125) n (%) |

SG (n = 121) n (%) |

||

| Age, years | |||

| n | 246 | 125 | 121 |

| Mean ± SD | 57.5 ± 10.1 | 56.8 ± 10.0 | 58.1 ± 10.1 |

| Education | |||

| Some HS, HS grad, GED | 59 (24.0) | 24 (19.2) | 35 (28.9) |

| Some college, associate’s degree, 2-year certificate | 93 (37.8) | 48 (38.4) | 45 (37.2) |

| College graduate | 47 (19.1) | 24 (19.2) | 23 (19.0) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 47 (19.1) | 29 (23.2) | 18 (14.9) |

| Combined family income, last 12 months, $ | |||

| < 20,000 | 58 (23.6) | 24 (24.0) | 28 (23.1) |

| 20,000–39,999 | 56 (22.8) | 25 (20.0) | 31 (25.6) |

| 40,000–59,999 | 48 (19.5) | 20 (16.0) | 28 (23.1) |

| 60,000–79,999 | 33 (13.4) | 18 (14.4) | 15 (12.4) |

| ≥ 80,000 | 50 (20.3) | 32 (25.6) | 18 (14.9) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| Cancer stage* | |||

| I | 85 (38.3) | 51 (44.0) | 34 (32.1) |

| II | 98 (44.1) | 46 (39.7) | 52 (49.1) |

| III | 39 (17.6) | 19 (16.4) | 20 (18.9) |

| Missing | 24 | 9 | 15 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (range 25.1–57.8) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 36.1 ± 6.2 | 35.9 ± 6.2 | 36.4 ± 6.4 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6-month weight change, kg | |||

| N | 210 | 110 | 100 |

| Mean ± SD | − 2.5 ± 4.3 | − 3.5 ± 4.7 | − 1.4 ± 3.5 |

| Missing | 36 | 15 | 21 |

| MVPA at baseline, min/wk (range 0–1023.5) | 246 | 125 | 121 |

| Mean ± SD | 164.0 ± 207.9 | 162.6 ± 188.5 | 165.5 ± 226.9 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6-month MVPA Change, min/wk | |||

| N | 212 | 111 | 101 |

| Mean ± SD | 89.1 ± 301.8 | 114.2 ± 248.7 | 61.6 ± 350.2 |

| Missing | 34 | 14 | 20 |

| HEI at baseline (range 38.9–93.9) | |||

| N | 221 | 112 | 109 |

| Mean ± SD | 65.1 ± 11.1 | 65.7 ± 11.4 | 64.4 ± 10.8 |

| Missing | 25 | 13 | 12 |

| 6-month HEI change | |||

| N | 190 | 100 | 90 |

| Mean ± SD | 5.0 ± 10.1 | 6.4 ± 10.0 | 3.3 ± 10.1 |

| Missing | 56 | 25 | 31 |

BMI body mass index, HEI healthy eating index, HS high school, IG interventionist-guided, MVPA moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, SD standard deviation, SG self-guided

Percent does not include missing

Self-efficacy, social support for eating and exercise, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months

Table 2 shows results for mean self-efficacy, social support for eating and exercise from family and friends, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety for IG and SG at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months. Baseline means were not significantly different for IG and SG. At 6 months, the IG group showed greater improvements in self-efficacy(p < 0.01); friend support for eating habits-encouragement (p = 0.03); family support for eating habits-encouragement (p = 0.01); and family support for exercise-participation (p = 0.02). SG group showed greater improvements for family support for eating habits-encouragement (p < 0.01); and friend support for eating habits-encouragement (p = 0.01).

Table 2.

Self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months

| Mediator | Baseline mean ± StDev N = 246 |

6 months N = 210 |

p value between groups 0–6 mo 0–6 within intervention 0–6 within control |

12 months N = 198 |

p value between groups 0–12 mo 0–12 within intervention 0–12 within control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy, range (21.0–99.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 72.4 ± 13.3 | 77.8 ± 13.31 | < 0.01 | 74.5 ± 13.4 | < 0.01 |

| Self-guided | 71.3 ± 13.2 | 69.6 ± 13.3 | 0.16 | 71.2 ± 13.9 | 0.19 |

| Family support for eating habits, encouragement, range (5.0–25.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 11.8 ± 5.7 | 13.0 ± 5.6 | 0.01 | 12.5 ± 5.8 | 0.61 |

| Self-guided | 10.7 ± 5.4 | 12.6 ± 5.9 | < 0.01 | 11.9 ± 5.9 | 0.18 |

| Family support for eating habits, discouragement, range (5.0–25.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 10.1 ± 4.5 | 10.8 ± 4.8 | 0.11 | 11.5 ± 5.3 | 0.47 |

| Self-guided | 9.4 ± 4.3 | 9.2 ± 3.7 | 0.37 | 10.4 ± 4.1 | 0.54 |

| Friend support for eating habits, encouragement, range (5.0–25.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 10.9 ± 5.5 | 12.0 ± 5.5 | 0.03 | 11.5 ± 5.1 | 0.49 |

| Self-guided | 10.5 ± 5.4 | 12.0 ± 5.5 | 0.01 | 10.9 ± 5.9 | 0.03 |

| Friend support for eating habits, discouragement, range (5.0–25.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 10.1 ± 4.5 | 10.8 ± 4.8 | 0.11 | 11.5 ± 5.1 | 0.35 |

| Self-guided | 9.4 ± 4.3 | 9.2 ± 3.7 | 0.37 | 9.5 ± 4.3 | 0.53 |

| Family support for exercise habits, participation, range (10.0–50.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 21.1 ± 9.8 | 23.2 ± 10.4 | 0.02 | 23.5 ± 13.7 | 0.69 |

| Self-guided | 21.3 ± 10.7 | 23.2 ± 10.8 | 0.12 | 23.9 ± 14.1 | 0.99 |

| Friend support for exercise habits, participation, range (10.0–50.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 20.9 ± 10.4 | 22.1 ± 0.1 | 0.07 | 21.0 ± 10.2 | 0.39 |

| Self-guided | 19.3 ± 9.3 | 20.2 ± 9.3 | 0.57 | 19.3 ± 9.5 | 0.23 |

| Perceived access to healthy eating (range 1.0–16.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 11.6 ± 3.0 | 12.6 ± 3.0 | < 0.01 | 12.6 ± 2.9 | 0.76 |

| Self-guided | 12.3 ± 2.9 | 12.5 ± 2.7 | 0.81 | 12.4 ± 2.8 | 0.60 |

| Perceived access to exercise (range 1.0–13.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 8.0 ± 2.5 | 9.5 ± 1.9 | < 0.01 | 9.5 ± 2.2 | 0.85 |

| Self-guided | 8.0 ± 2.5 | 8.4 ± 2.4 | 0.09 | 8.7 ± 2.4 | 0.11 |

| Perceived neighborhood safety (range 1.0–13.0) | |||||

| Interventionist-guided | 8.0 ± 1.8 | 8.0 ± 1.7 | 0.83 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 0.37 |

| Self-guided | 8.0 ± 1.6 | 8.2 ± 1.9 | 0.52 | 8.3 ± 1.8 | 0.30 |

Are self-efficacy, social support for eating and exercise, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety associated with post-intervention weight loss and/or changes in MVPA or diet?

Table 3 shows results for self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety, regressed on weight, MVPA, and diet. In adjusted models for age, income, education, breast cancer diagnosis, group, and time, higher self-efficacy (β = − 0.067, p < 0.001), and friend support for eating habits- discouragement (β = − 0.16, p = 0.001) were associated with weight loss. For MVPA, self-efficacy (β = 2.07, p = 0.019), friend support for exercise habits-participation (β = 2.613, p = 0.049), and higher perceived access to exercise (β = 15.329, p = 0.005) were associated with increased minutes per week of MVPA. For diet, higher self-efficacy (β = 0.154, p < 0.001) and lower friend support for eating habits-discouragement (β = 0.238, p = 0.014) were associated with improvements in diet.

Table 3.

Self-efficacy; social support; and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety regressed on weight, MVPA, and diet

| Parameter | Weight loss |

MVPA |

Diet |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A |

Model 1B |

Model 1C |

|||||||

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| Intercept | 133.12 | 8.26 | < 0.001 | − 50.52 | 138.65 | 0.716 | 37.26 | 5.57 | < 0.001 |

| Group | |||||||||

| 1 Interventionist-guided | − 0.85 | 2.40 | 0.724 | − 17.35 | 28.18 | 0.539 | 0.90 | 1.19 | 0.452 |

| 2 Self-guided | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Time 2–6 months | − 2.30 | 0.31 | < 0.001 | 58.19 | 20.26 | 0.004 | 4.58 | 0.73 | < 0.001 |

| Time 3–12 months | − 2.02 | 0.32 | < 0.001 | 74.91 | 20.54 | 0.000 | 3.78 | 0.74 | < 0.001 |

| Time 1-baseline | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Self-efficacy | − 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.000 | 2.07 | 0.88 | 0.019 | 0.15 | 0.03 | < 0.001 |

| Family support for eating habits | |||||||||

| Encouragement | − 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.434 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 0.318 | − 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.927 |

| Discouragement | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.294 | 2.37 | 2.58 | 0.359 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.014 |

| Friend support for eating habits | |||||||||

| Encouragement | − 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.576 | − 1.10 | 2.44 | 0.654 | − 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.254 |

| Discouragement | − 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.71 | 2.65 | 0.790 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.084 |

| Family support for exercise habits | |||||||||

| Participation | − 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.110 | −0.27 | 0.96 | 0.779 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.183 |

| Friend support for exercise habits | |||||||||

| Participation | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.649 | 2.61 | 1.32 | 0.049 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.114 |

| Perceived access to healthy eating | − 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.054 | − 1.43 | 4.15 | 0.731 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.902 |

| Perceived access to exercise | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.356 | 15.33 | 5.47 | 0.005 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.327 |

| Perceived neighborhood safety | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.396 | 8.33 | 6.56 | 0.205 | − 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.725 |

| AICC (smaller is better) | 3872.00 | 7983.80 | 4070.00 | ||||||

| SBC (smaller is better) | 3878.80 | 7990.60 | 4076.80 | ||||||

Do these factors mediate the association between group and outcome?

Formal mediation tests (Freedman Schatzkin) were conducted to examine whether self-efficacy, social support and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety mediated the association between group and change in weight loss, MVPA, or diet; we found no evidence to suggest a mediating effect.

Discussion

This study examined the extent to which self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to healthy eating, exercise, and neighborhood safety facilitated changes in weight loss and behavior (i.e., MVPA and diet) and found no evidence to suggest mediation, but some direct associations of self-efficacy, certain types of social support and perceived access to exercise on weight loss, and behavior change (i.e., MVPA and diet).

Increases in self-efficacy reflect improvements in the participant’s confidence to achieve weight loss, MVPA, and dietary change over the course of the MF intervention. These improvements were correlated with weight loss and behavior change (i.e., MVPA and diet) and are supported by at least three studies of home and community-based interventions of early-stage predominately white and Asian, breast and other cancer survivors [36-38]. We extend their results by showing this association among a large community-based sample of AABCS participating in a group-based weight loss intervention. Our findings, in combination with other studies, lend credence to the notion that self-efficacy plays an important role in the initiation and maintenance of health behavior change posited by social cognitive theory [14]. In particular, we showed that access to twice-weekly in-person classes with supervised exercise and targeted text messaging among the IG group contributed to improvements in self-efficacy in the majority of IG participants, which may have led to greater weight loss and improvements in MVPA and diet. This is compared to the SG group who received the intervention binder only and, in which approximately a third of participants showed increased self-efficacy. These results support the value of an intensive intervention with interventionist-guided classes and targeted text messaging to improve self-efficacy to facilitate weight loss and behavior changes.

Our findings for social support, weight loss, and behavior change are consistent with one other study. We found that women with less discouragement from friends for eating habits were associated with improvements in weight loss and diet. In addition, we found that more friend support for exercise habits-participation was associated with higher physical activity. These findings are consistent with Rieger et al. who found that greater discouragement from family and friends for eating habits was associated with problem eating behaviors and negative attitude towards weight loss [39]. In contrast, Kiernan et al. found that women who experienced the most discouragement from friends for eating habits lost the most weight [40]. Taken together, our findings show that discouragement from friends and family can lead to problem eating behaviors. Future studies may want to focus on ways to reduce the negative impact of friends and family through teaching ways to cope with discouragement or providing ways to communicate with family and friends in order to counter their negative comments. Interventions could also target family and friends to teach them how to create positive environments to support weight loss and behavior change.

Many of our measures of social support were not associated with weight loss or behavior change. This may have been due to the conceptualization of our measure of social support. Social support is typically conceptualized as something positive [15] and few measures include items aimed to capture negative affect. In our study, participants might have interpreted items as being positive (encouraging) or negative (discouraging) [35]. For example, the questionnaire asked participants to respond “never to very often” to the following question: “During the past 3 months, your family commented if you went back to your old eating habits.” Although this item was included on the positive subscale for family support for eating habits, it may also be considered as negative or controlling behavior. Similarly, other items in the encouragement subscale could be perceived as negative depending on the person’s intention or tone. At least one study has shown social support may be perceived as either beneficial or a source of stress or conflict [41]. Further, Cohen et al. have shown that the timing of social support may result in negative consequences [42]. We were not able to disentangle these underlying factors, since we did not capture whether the participant viewed each social support item measured as supportive or not. However, our factor analysis did show items in the encouragement and discouragement subscores loaded as expected. In other intervention and observational studies with Non-Latina White and Latina BC survivors, higher social support is correlated with more MVPA [43, 44] and better diet [45]. However, these studies used a more general measure of social support, as opposed to the one we used which focuses specifically on support related to healthy eating and exercise behaviors. Future research should elicit more nuanced information on how participants experience and interpret various types of social support to distinguish between social support and negative interactions.

In addition to self-efficacy and social support, we expected environmental factors, in particular increases in perceived access to exercise resources as a result of their intervention participation would be associated with participants’ outcomes. Our main finding was that higher perceived access to exercise was associated with higher physical activity, irrespective of group (i.e., IG or SG), but not weight loss or diet. We did not find evidence to suggest that perceived access to healthy eating or neighborhood safety was associated with weight loss, or behavior change. IG participants attended intervention sessions at a local Chicago Park District (CPD) facility, and also had access to the facility’s classes and fitness resources. Prior to the MF intervention, many women had little knowledge of the breadth of CPD resources. Not surprisingly, the majority of IG participants reported improvements in perceived access to exercise compared to just over half of SG participants. The intervention also focused on identifying healthy food shopping resources within and around each intervention setting (i.e., farmers markets) and discussing ways to facilitate access (ask local grocers to stock certain foods). These findings lend support to the recommendation that directly addressing improved access to healthy eating and exercise resources is an essential component to improving the effectiveness of interventions among AABCS [46-48].

Although changes in self-efficacy, social support, and perceived access to exercise were associated with weight loss and behavior change, these factors did not mediate the relationship between the group and weight loss, MVPA, and diet as expected. The lack of a true control group may have impacted these results. For ethical reasons and based on strong survivor feedback, we chose to include a comparison group where participants received some information, rather than a true control group. The SG group received a binder with the course curriculum. Post-intervention, both groups exhibited weight loss and health behavior changes, with greater changes observed in the IG. Future studies, may use a lagged-design where the comparison group receives the intervention following the intervention group in order to create a control group to better examine intervention effects [49].

Our study is not without limitations. Although we collected measures over time and saw significant changes, we cannot suggest causality between factors, and thus can only show associations. Another limitation is MVPA and dietary intake were self-reported, which can lead to underreporting or overreporting. However, we used validated instruments widely used in cancer survivor studies [29, 32]. The strengths of this study are the randomized design, the focus on an underserved population, analyses of hypothesized mediators, and the use of validated measures.

Conclusion/Implications

In conclusion, improving self-efficacy, and perceived access to exercise were key areas that supported weight loss and behavior change among AABCS. Future studies should examine objective measures of access to exercise and their associations with weight loss and behavior and compare these with subjective measures of access to better inform future interventions. In addition, social support from friends for exercise also influenced weight loss and behavior change. By facilitating a group intervention, we created an environment that increased social support from friends for exercise, which positively influenced weight loss and behavior change. However, many of the subscales used to measure social support showed no association, additional measurements for social support may be needed to better capture the type of social support women experience.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the participants who devoted time and energy to this trial and to the Chicago Park District. A special thanks to Alexis Visotcky for advice on statistical analyses.

Funding

This funding was supported by National Cancer Institute [Grant No.CA154406] and Health Resources and Services Administration [Grant No. T32HP10030].

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Alcaraz KI, Jemal A (2016) Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA: Cancer J Clin 66(4):290–308. 10.3322/caac.21340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coughlin SS, Yoo W, Whitehead MS, Smith SA (2015) Advancing breast cancer survivorship among African-American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 153(2):253–261. 10.1007/s10549-015-3548-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Shields AE (2016) Understanding and effectively addressing breast cancer in African American women: unpacking the social context. Cancer. 10.1002/cncr.29935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan DSM, Vieira AR, Aune D, Bandera EV, Greenwood DC, McTiernan A, Navarro Rosenblatt D, Thune I, Vieira R, Norat T (2014) Body mass index and survival in women with breast cancer—systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 82 follow-up studies. Ann Oncol 25(10):1901–1914. 10.1093/annonc/mdu042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenlee HA, Crew KD, Mata JM, McKinley PS, Rundle AG, Zhang W, Liao Y, Tsai WY, Hershman DL (2013) A pilot randomized controlled trial of a commercial diet and exercise weight loss program in minority breast cancer survivors. Obesity 21(1):65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenlee H, Shi Z, Molmenti CLS, Rundle A, Tsai WY (2016) Trends in obesity prevalence in adults with a history of cancer: results from the US National Health Interview Survey, 1997 to 2014. J Clin Oncol 34(26):3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Burger RA, Chlebowski RT, Fabian CJ, Gucalp A, Hershman DL, Hudson MM (2014) American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. J Clin Oncol 32(31):3568–3574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paxton RJ, Garner W, Logan G, Dean LT, Allen-Watts K (2019) Health behaviors and lifestyle interventions in African American breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Front Oncol 9:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stolley M, Sheean P, Gerber B, Arroyo C, Schiffer L, Banerjee A, Visotcky A, Fantuzzi G, Strahan D, Matthews L, Dakers R, Carridine-Andrews C, Seligman K, Springfield S, Odoms-Young A, Hong S, Hoskins K, Kaklamani V, Sharp L (2017) Efficacy of a weight loss intervention for African American breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 35(24):2820–2828. 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.9856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Oh A, Schiffer L (2009) A weight loss intervention for African American breast cancer survivors, 2006. Prev Chronic Dis 6(1):A22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spector D, Battaglini C, Groff D (2013) Perceived exercise barriers and facilitators among ethnically diverse breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 40(5):472–480. 10.1188/13.onf.472-480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyekanmi G, Paxton RJ (2014) Barriers to physical activity among African American breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 23(11):1314–1317. 10.1002/pon.3527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong S, Bardwell WA, Natarajan L, Flatt SW, Rock CL, Newman VA, Madlensky L, Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE, Thomson CA, Hajek RA, Chilton JA, Pierce JP (2007) Correlates of physical activity level in breast cancer survivors participating in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 101(2):225–232. 10.1007/s10549-006-9284-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall Inc, Englewood Cliffs, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heaney CA, Israel BA (2008) Social networks and social support. Health Behav Health Educ 4:189–210 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barber FD (2012) Social support and physical activity engagement by cancer survivors. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 10.1188/12.CJON.E84-E98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoedjes M, van Stralen MM, Joe STA, Rookus M, van Leeuwen F, Michie S, Seidell JC, Kampman E (2017) Toward the optimal strategy for sustained weight loss in overweight cancer survivors: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv 11(3):360–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheppard VB, Hicks J, Makambi K, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Demark-Wahnefried W, Adams-Campbell L (2016) The feasibility and acceptability of a diet and exercise trial in overweight and obese black breast cancer survivors: the Stepping STONE study. Contemp Clin Trials 46:106–113. 10.1016/j.cct.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djuric Z, Mirasolo J, Kimbrough L, Brown DR, Heilbrun LK, Canar L, Venkatranamamoorthy R, Simon MS (2009) A pilot trial of spirituality counseling for weight loss maintenance in African American breast cancer survivors. J Natl Med Assoc 101(6):552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones A, Paxton RJ (2015) Neighborhood disadvantage, physical activity barriers, and physical activity among African American breast cancer survivors. Prev Med Rep 2:622–627. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walcott-McQuigg JA, Prohaska TR (2001) Factors influencing participation of African American elders in exercise behavior. Public Health Nurs 18(3):194–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bronner Y, Boyington JE (2002) Developing weight loss interventions for African-American women: elements of successful models. J Natl Med Assoc 94(4):224–235 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfe WA (2004) A review: maximizing social support-A neglected strategy for improving weight management with African-American women. Ethn Dis 14(2):212–218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haughton CF, Silfee VJ, Wang ML, Lopez-Cepero AC, Estabrook DP, Frisard C, Rosal MC, Pagoto SL, Lemon SC (2018) Racial/ethnic representation in lifestyle weight loss intervention studies in the United States: a systematic review. Prev Med Rep 9:131–137. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulz AJ (2011) Urban environments and health. In: Nriagu J (ed) Encyclopedia of environmental health. Elsevier, Burlington, MA, pp 549–555 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shariff-Marco S, Yang J, John EM, Sangaramoorthy M, Hertz A, Koo J, Nelson DO, Schupp CW, Shema SJ, Cockburn M (2014) Impact of neighborhood and individual socioeconomic status on survival after breast cancer varies by race/ethnicity: the Neighborhood and Breast Cancer Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 10.1158/1055-9965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beyer KM, Zhou Y, Matthews K, Bemanian A, Laud PW, Nattinger AB (2016) New spatially continuous indices of redlining and racial bias in mortgage lending: links to survival after breast cancer diagnosis and implications for health disparities research. Health Place 40:34–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Fantuzzi G, Arroyo C, Sheean P, Schiffer L, Campbell R, Gerber B (2015) Study design and protocol for moving forward: a weight loss intervention trial for African-American breast cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 15:1018. 10.1186/s12885-015-2004-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kriska AM, Caspersen CJ (1997) Introduction to a collection of physical activity questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc 29(6):5–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irwin ML, Crumley D, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, Baumgartner R, Gilliland FD, Kriska A, Ballard-Barbash R (2003) Physical activity levels before and after a diagnosis of breast carcinoma. Cancer 97(7):1746–1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Block G, Hartman AM, Naughton D (1990) A reduced dietary questionnaire: development and validation. Epidemiology 1:58–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Block G, Wakimoto P (1998) A revision of the Block Dietary Questionnaire and database, based on NHANES III data. University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hiza HA, Kuczynski KJ, Kahle LL, Krebs-Smith SM (2013) Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet 113(4):569–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latimer L, Walker LO, Kim S, Pasch KE, Sterling BS (2011) Self-efficacy scale for weight loss among multi-ethnic women of lower income: a psychometric evaluation. J Nutr Educ Behav 43(4):279–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR (1987) The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med 16(6):825–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett JA, Lyons KS, Winters-Stone K, Nail LM, Scherer J (2007) Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res 56(1):18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YJ, Boehmke M, Wu YW, Dickerson SS, Fisher N (2011) Effects of a 6-week walking program on Taiwanese women newly diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 34(2):E1–13. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181e4588d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosher CE, Lipkus I, Sloane R, Snyder DC, Lobach DF, Demark-Wahnefried W (2013) Long-term outcomes of the FRESH START Trial: exploring the role of self-efficacy in cancer survivors’ maintenance of dietary practices and physical activity. Psycho-Oncology 22(4):876–885. 10.1002/pon.3089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rieger E, Sellbom M, Murray K, Caterson I (2018) Measuring social support for healthy eating and physical activity in obesity. Br J Health Psychol 23(4):1021–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiernan M, Moore SD, Schoffman DE, Lee K, King AC, Taylor CB, Kiernan NE, Perri MG (2012) Social support for healthy behaviors: scale psychometrics and prediction of weight loss among women in a behavioral program. Obesity 20(4):756–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uchino BN (2004) Social support and physical health: understanding the health consequences of relationships. Yale University Press, New Haven [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH (2000) Social support measurement and intervention: a guide for health and social scientists. Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kampshoff CS, Stacey F, Short CE, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ, Brug J, Plotnikoff R, James EL, Buffart LM (2016) Demographic, clinical, psychosocial, and environmental correlates of objectively assessed physical activity among breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24(8):3333–3342. 10.1007/s00520-016-3148-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olson EA, Mullen SP, Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Verhulst S, McAuley E (2014) Meeting physical activity guidelines in rural breast cancer survivors. Am J Health Behav 38(6):890–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crookes DM, Shelton RC, Tehranifar P, Aycinena C, Gaffney AO, Koch P, Contento IR, Greenlee H (2016) Social networks and social support for healthy eating among Latina breast cancer survivors: implications for social and behavioral interventions. J Cancer Surviv 10(2):291–301. 10.1007/s11764-015-0475-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kong A, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Odoms-Young AM, Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML (2014) Systematic review of behavioural interventions with culturally adapted strategies to improve diet and weight outcomes in African American women. Obes Rev 15(Suppl 4):62–92. 10.1111/obr.12203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dean LT, Gehlert S, Neuhouser ML, Oh A, Zanetti K, Goodman M, Thompson B, Visvanathan K, Schmitz KH (2018) Social factors matter in cancer risk and survivorship. Cancer Causes Control 29(7):611–618. 10.1007/s10552-018-1043-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joseph RP, Ainsworth BE, Keller C, Dodgson JE (2015) Barriers to physical activity among African American women: an integrative review of the literature. Women Health 55(6):679–699. 10.1080/03630242.2015.1039184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Mentz GB, Bernal C, Caver D, DeMajo R, Diaz G, Gamboa C, Gaines C, Hoston B, Opperman A, Reyes AG, Rowe Z, Sand SL, Woods S (2015) Effectiveness of a walking group intervention to promote physical activity and cardiovascular health in predominantly non-Hispanic black and Hispanic urban neighborhoods: findings from the walk your heart to health intervention. Health Educ Behav. 10.1177/1090198114560015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]