SUMMARY

2′-O-methylation (Nm) is a prominent RNA modification well known in noncoding RNAs and more recently also found at many mRNA internal sites. However, their function and base-resolution stoichiometry remain under-explored. Here, we investigated the transcriptome-wide effect of internal site Nm on mRNA stability. Combining Nanopore sequencing with our developed machine-learning method, NanoNm, we identified thousands of Nm sites on mRNAs with a single-base resolution. We observed a positive effect of FBL-mediated Nm modification on mRNA stability and expression level. Elevated FBL expression in cancer cells is associated with increased expression levels for 2′-O-methylated mRNAs of cancer pathways, implying the role of FBL in post-transcriptional regulation. At last, we found FBL-mediated 2′-O-methylation connected to widespread 3′ UTR shortening, a mechanism that globally increases RNA stability. Collectively, we demonstrated that FBL-mediated Nm modifications at mRNA internal sites regulate gene expression by enhancing mRNA stability.

Keywords: FBL, 2′-O methylation, RNA stability, Nanopore

In brief:

Li et al. developed a machine-learning approach to measure the stoichiometry of 2′-O-methylation at internal sites of mRNA using Nanopore RNA sequencing data. FBL-mediated Nm modifications, connected to widespread shortening of the 3′ UTR, regulate gene expression by enhancing mRNA stability.

INTRODUCTION

RNA modifications play pivotal roles in regulating RNA processing and translation1. Detecting RNA modifications at individual sites is a key step to understanding their function and regulation. To date, at least 163 types of RNA modifications have been identified2. However, only a handful of these modifications, including m6A3, pseudo uridine (Ψ)4, m5C5, inosine6, m1A7,8, m7G9, and N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C)10,11, have been detectable on mammalian mRNAs. 2′-O-methylation (Nm) frequently happens on rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, microRNA, and the cap of mRNA12. Recently, transcriptome-wide profiling based on next-generation sequencing approaches revealed that Nm also happens at mRNA internal sites13–15. Two recent studies on a single gene indicated that internal Nm on mRNA affects the mRNA expression level16 and mRNA decoding by tRNA17. It is unknown whether these effects happen on other mRNAs. Recent studies revealed that some RNA modifications, such as the m6A18, m5C19,20, Ψ21, ac4C10, and A to I editing, affect mRNA stability. On the other hand, multiple sequence-encoded features also have been implicated in regulating mRNA half-life, e.g., guanine-cytosine (GC) content, length of three prime untranslated regions (3′ UTR), binding sites of microRNA (miRNA), AU-rich elements, and codon frequencies22. Till now, the function of the Nm at mRNA internal sites in the cells, e.g., the effect on mRNA stability and the underlying mechanism, is yet unclear.

As the most abundant RNA modification on rRNAs, Nm modifications play an essential role during rRNA processing, ribosome biogenesis, and translation23,24. In sharp contrast to this well-known role on rRNA, the function of Nm at mRNA internal sites is currently unclear. It is well established that C/D-box small nucleolar RNAs guide RNA methyltransferase Fibrillarin (FBL), which forms a complex with its partner proteins such as the NOP56, NOP58, and SNU13, to catalyze Nm on rRNA25–27. In addition, FBL plays essential roles in many biological processes such as histone H2AQ104 methylation28, stem cell pluripotency29, neuronal differentiation30, and eye and craniofacial development31. Oncogenic roles of FBL in Nm of rRNAs were also reported, e.g., in prostate cancer (PCa)23,24 and breast cancer32. However, we know little about the oncogenic role of Nm at mRNA internal sites and the relevance of FBL in this modification.

Most methods that detect RNA modification rely on either antibody, chemical treatment, or reverse transcription errors, which are powerful, but each also has some limitations, e.g., introducing some biases and artifacts33. As outstanding examples of such methods, the Nm-seq13 and Nm-Mut-seq14 enabled transcriptome-wide detection of Nm sites, showing Nm modifications at widespread internal sites of mRNA. However, a quantitative way to directly measure the transcriptome-wide Nm modification with stoichiometric information is still lacking. Nanopore direct RNA-seq represents a promising approach to concurrently detect multiple types of RNA modifications based on electrical signals of the nucleotides34–36. This cutting-edge method was utilized to map RNA modifications including m6A33,37–40, Ψ41,42, m5C43, and A-to-I editing in different species44. In terms of Nm, despite analysis of sequencing signals at known Nm sites in rRNA42,45 and prediction of Nm sites as “yes” or “no” events in mRNA46, there is yet no algorithm for de novo measurement of Nm stoichiometry using Nanopore direct RNA sequencing42.

In this study, we first investigated the effect of Nm modification and the binding of FBL on mRNA stability in FBL- and NOP56-deficient versus control cells. We then investigated the regulation of mRNA Nm modification based on a machine learning model, which utilized key features of known Nm sites in the rRNAs to detect mRNA Nm sites based on direct RNA-seq data generated by the Oxford Nanopore Technologies™ (ONT) sequencer. In addition to accurately recapturing the well-known Nm sites in rRNA, the model further identified about 30,000 internal Nm sites on mRNAs. We demonstrated that FBL depletion decreased the RNA Nm levels, stability, and expression. By precisely measuring the stoichiometry of Nm at base resolution in mRNAs, we revealed the oncogenic role of FBL in Nm-mediated post-transcriptional regulation of mRNA stability in cancer cells. Mechanically, we found Nm connected to alternative polyadenylation, which leads to 3′ UTR shortening and thus increased mRNA stability. These findings highlight the function of Nm in stabilizing mRNAs across the transcriptome.

RESULTS

Nm at mRNA internal sites is positively associated with mRNA stability

To investigate the association between Nm and mRNA stability (Figure 1A), we started with an integrative analysis of multiple public datasets. We collected mRNA half-life data determined by RNA-seq following Actinomycin D (ActD) inhibition of transcription in HEK293T cells47. We also collected mRNA Nm data determined by Nm-seq in HEK293T cells13. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) indicated that 2′-O-methylated mRNAs were enriched in mRNAs with a long half-life (Figure 1B). Compared to control mRNAs, the half-lives of 2′-O-methylated mRNAs were significantly longer (Figure 1C). Because FBL is one of the enzymes well known to catalyze Nm and NOP56 is required to facilitate the reaction, we performed RNA-Seq following ActD inhibition of transcription to profile RNA half-life in control, FBL-knockdown and NOP56-knockdown HEK293T cells (Figure 1D, Figure S1A–C, Table S1). When compared to mRNAs that have no detectable Nm in the control cells, the 2′-O-methylated mRNAs were significantly more likely to show a decrease in mRNA half-life in response to the knockdown of FBL or NOP56 (Figure 1E–F). The half-lives of 2′-O-methylated mRNAs were decreased in FBL knockdown and NOP56 knockdown cells than in control cells (Figure 1G–H). These data indicated that the Nm modifications at mRNA internal sites are positively associated with greater stability of the mRNAs.

Figure 1. Nm at internal sites on mRNA and the expression of Nm writer protein FBL is required for the greater stability of 2′-O-methylated mRNAs compared to the rest of mRNAs.

(A) A cartoon to show Nm (top panel) and related questions on RNA stability (bottom). (B) GSEA showing a relationship between 2′-O-Methylation and mRNA half-life. (C) Cumulative and boxplot to show the half-life of mRNAs with or without detectable Nm. (D) Western blot to show the knockdown efficiency of FBL and NOP56 in C4–2 cells. (E-F) Cumulative fraction of mRNAs plotted against the change of mRNA half-life in response to knockdown of FBL (E) and NOP56 (F). (G) Boxplot to show the half-life of 2′-O-methylated mRNAs under individual conditions. (H) Heatmap showing half-life of top 2′-O-methylated mRNAs ranked by degree of half-life decrease upon FBL knockdown. P values were determined by two-tailed unpaired Wilcoxon’s test (boxplot in C, G) and K-S test (cumulative plot in C, E, F). All presented data were from HEK293T cells (Nm genes: n = 691). RNA half-life determined based on public (B-C) and our own (E-H) RNA-seq data generated following ActD inhibition of transcription. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

The binding of FBL on mRNA is positively associated with mRNA stability and required for mRNA Nm modification

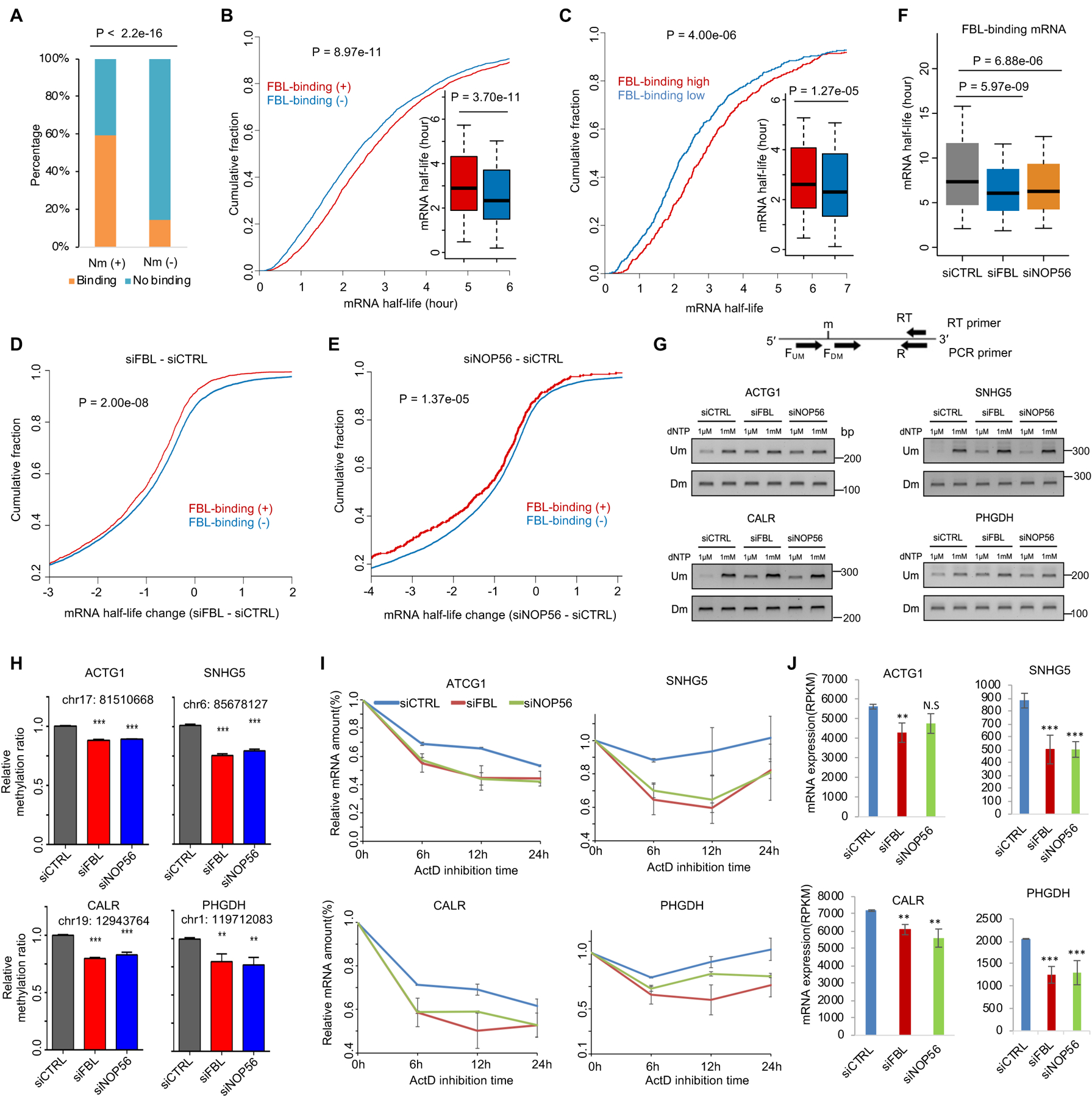

It is well known that FBL could methylate rRNA at many positions, but it was under-explored whether FBL could methylate mRNA extensively. We analyzed a PAR-CLIP-seq dataset from HEK293T cells48. Consistent with a previous report13, we found FBL-binding mRNAs overlapped significantly with 2′-O-methylated mRNAs (Figure 2A, Figure S1D). About 60% of the Nm-modified transcripts exhibit FBL binding, in contrast to only 10% of unmethylated transcripts (Figure 2A). We next used the genes of FBL-binding mRNAs48,49 from HEK293T cells together with the mRNA half-life data47 to determine whether the binding of FBL is required to regulate the mRNA stability. Like the mRNAs with Nm (Figure 1C, S1E), the FBL-binding mRNAs showed significantly longer mRNA half-life when compared to the mRNAs showing no detectable binding of FBL (Figure 2B, Figure S1F). Among FBL-binding mRNAs, the mRNAs with a higher FBL-binding intensity appeared more stable (Figure 2C, S1G). To investigate if mRNA stability relies on FBL, we further analyzed the half-life change of FBL-binding mRNA in response to the knockdown of FBL and NOP56. We observed a significant reduction in half-life for FBL-binding mRNAs compared to those without detectable FBL binding in wild-type cells (Figure 2D–E). The reduction in the half-life of FBL-binding mRNAs was significant in response to FBL knockdown and NOP56 knockdown (Figure 2F, Figure S1H).

Figure 2. The binding of FBL is required for the greater stability of FBL-binding mRNAs when compared to the rest of the mRNAs.

(A) Bar plot showing the overlap of 2′-O-methylated mRNAs and FBL-binding mRNAs. (B) Cumulative fraction of mRNAs plotted against half-life of mRNAs with (n = 2772) or without (n = 2772) detectable binding of FBL. (C) Cumulative fraction of mRNAs plotted against half-life of mRNAs with high (n = 500) or low (n = 500) binding intensity of FBL. (D-E) Cumulative fraction of mRNAs plotted against the change of mRNA half-life in response to knockdown of FBL (D) and NOP56 (E). (F) Half-life of FBL-binding mRNAs under three different conditions. (G) RTL-P assay detected Nm level on four mRNAs (ACTG1, SNHG5, CALR, PHGDH) under control, siFBL, and siNOP56 conditions. (H) Densitometric analysis of data from (G) was shown as the signal intensity ratio of PCR products at low dNTP (1 μM) over high dNTP (1 mM) conditions. The ratio in control cells was set to 1. Data represent Mean ± SD from n = 3 biologically experiments. **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001. (I) Relative expression level of mRNA plotted against time after inhibition of transcription in each panel. Expression was determined by RNA-Seq (n = 2) and normalized to the 0-hour point. (J) Bar plot to show steady-state mRNA expression level determined by RNA-Seq. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 were calculated by edgeR. P values were determined by a two-tailed K-S test (B, C, D, E) and Student’s t-test (H). All presented data were from HEK293T cells. RNA half-life determined based on public (A-C) and our own (E-F) RNA-seq data from ActD inhibition method. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

To determine if FBL is required for Nm modification on mRNAs, we thus used RTL-P assay50, a sensitive method widely used, to confirm the Nm of ACTG1, PGHDH, SNHG5, and CALR, which are bound by FBL and 2′-O-methylated. Depletion of FBL and NOP56 both increased the reverse transcription products at low dNTP concentrations but not at high dNTP concentrations, suggesting a significant decrease in Nm levels on all four mRNAs (Figure 2G–H). The half-life and expression levels of these four mRNAs decreased upon the knockdown of FBL and NOP56 (Figure 2I–J, Figure S1H). Together, we verified that FBL is critical for mRNA Nm modification and, thus, to stabilize these mRNAs.

Upregulation of FBL is associated with increased stability and expression levels of FBL-binding mRNAs in cancer cells

Consistent with previous reports that FBL is overexpressed in cancer23,24,32, our analysis of TCGA patient data51 confirmed that FBL, NOP56, and NOP58, were up-regulated in most of the cancer types (Figure S2A–C), including the PCa (Figure 3A). We also compared the prostate primary epithelial cell PrEC with PCa cell line C4–252 and found higher RNA expression levels of FBL, NOP56, and NOP58 in C4–2 cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Elevated FBL expression correlated with expression upregulation of FBL-binding and 2′-O-methylated mRNAs in PCa cells.

(A) Boxplot showing RNA expression level of FBL, NOP56, and NOP58 in prostate normal (n = 52) and cancer (n = 497) samples from the TCGA project. (B) Genome browser tracks showing RNA-Seq read density at individual gene loci. (C) A pie chart showing the distribution of FBL-binding sites in individual categories of RNAs in C4–2 cells. (D) GSEA result shows the relationship between the binding of FBL on mRNA and the expression change of mRNA in response to FBL knockdown. (E) Expression change of mRNAs in response to FBL knockdown. (F) Cumulative fraction of mRNAs plotted against the change of mRNA half-lives in response to FBL knockdown. (G) mRNA half-life of FBL-binding mRNAs under two conditions. (H) Cumulative and boxplot of half-life change of mRNAs between C4–2 and PrEC cells. (I) GSEA to show the relationship between the binding of FBL on mRNA in C4–2 cells and the expression change of mRNA between C4–2 and PrEC cells. (J) Expression of FBL-binding mRNAs between C4–2 and PrEC cells. FBL-binding mRNAs (n = 1886) in all figures were defined in the C4–2 cells. P-values were determined by two-tailed unpaired Wilcoxon’s tests (A, E, G, boxplot in H, J) and K-S test (F, cumulative curve in H). See also Figure S2 and Table S2.

Knockdown of FBL could inhibit PCa progression by regulating Nm methylation of rRNA and thus IRES-dependent translation of oncogenes23. However, it is unclear if the oncogenic role of FBL also depends on direct binding and regulation of mRNAs. To investigate this unrecognized role of FBL, we performed RIP-seq in C4–2 cells to identify FBL-binding RNAs (Figure S2D). Consistent with previous findings48,53, we found that nearly 80% of the FBL-binding RNAs in C4–2 cells were protein-coding genes (Figure 3C, Table S2). Among the FBL-binding transcripts in C4–2 cells, 1377 transcripts were bound by FBL in both C4–2 and HEK293T cells, whereas FBL bound 3468 transcripts in C4–2 specifically (Figure S2E). The C4–2 data also confirmed that FBL could bind to CD-box snoRNAs and mRNAs (Figure 3C and Figure S2F–H).

We next investigated if FBL regulates the expression of FBL-binding mRNAs in C4–2 cells. We observed that FBL-binding mRNAs were significantly enriched with down-regulated mRNAs upon FBL knockdown (Figure 3D). FBL-binding mRNAs showed significantly lower RNA expression levels (Figure 3E) and shorter half-lives (Figure 3F, Table S3) following FBL knockdown compared to mRNAs without detectable FBL binding. The half-lives of FBL-binding mRNAs appeared significantly shorter in the FBL knockdown cells than in control cells (Figure 3G). Also, compared to control mRNAs without FBL binding, the FBL-binding mRNAs in C4–2 cells were up-regulated in C4–2 cells relative to PrEC (Figure 3H). The genes of FBL-binding mRNAs in C4–2 cells showed higher expression levels in C4–2 cells compared to PrEC cells (Figure 3I–J). These data suggested that the binding of FBL on mRNAs upregulated the mRNA expression level by increasing their mRNA stability.

A machine learning model to detect Nm sites in mRNAs by Nanopore sequencing

Till now, Nm at mRNA internal sites has not yet been studied in cancer. This is partly due to the lack of a robust technique to measure Nm stoichiometry across the transcriptome. To fill this gap, we adopted Nanopore direct RNA-seq with machine learning techniques to detect mRNA Nm modifications with stoichiometry. Recently, the XGBoost machine learning method was applied to detect RNA modifications such as m6A37 and Nm46. However, the algorithm to de novo detect and measure the stoichiometry of Nm on mRNA is lacking. We customized the XGBoost machine learning method to use reported rRNA Nm sites as the training data, as these sites have a high Nm ratio compared to a low Nm ratio at sites on mRNA. Also, rRNA Nm sites have been very well studied using riboMeth-seq54–56, 2′-OMe-Seq57, and RibOxi-Seq58. We collected the 107 well-known Nm sites reported for 5.8S, 18S, and 28S rRNAs in human59. After that, using the public Nanopore direct RNA-seq dataset for rRNAs as positive data and in vitro-transcribed (IVT) RNAs without any modification as negative data, we trained an XGBoost machine-learning model for the 107 sites containing one hundred 5-mers from rRNAs (Figure 4A, Figure S3A). For these 5-mers, the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) and model performance accuracy were ranged from 0.98 to 0.99 and from 0.92 to 0.94, respectively (Figure 4B, Figure S3B–C), indicating robustness and high precision.

Figure 4. A machine learning model for detection of Nm based on Nanopore direct RNAseq.

(A) Flowchart of the machine learning model to detect Nm based on Nanopore direct RNA-seq. (B) ROC curves showing the performance of the machine learning model for two different 5-mers in KTC-1 cells. (C, D) Nm modification ratio at individual sites on the 28S (C) and 18S (D) rRNAs of C4–2 cells. (E, F) Nm modification ratios at individual sites on 28S rRNA (E) and 18S rRNA (F) in siCTRL and siFBL C4–2 cells. (G) rRNA Nm modification ratio at known snoRNA-targeted Nm sites on 25S rRNA in yeast under wild type, snR60, snR61, and snR62 knockout conditions. (H, I) Nm modification ratio at individual sites on 28S rRNA (H) and 18S rRNA (I) in siCTRL and siFBL Drosophila cells. (J) Density plot of Nm modification ratio for mRNAs and rRNAs in C4–2 cells. (K) A pie chart shows the distribution of Nm sites in different sequence regions. P values were determined by two-tailed unpaired Wilcoxon’s tests (E, F, H, I). See also Figure S3 and Table S3.

We then applied this machine learning model to our Nanopore direct RNA-seq datasets from control and FBL-deficient C4–2 cells (Figure S3D, Table S4). The model recaptured the reported Nm sites of rRNA (Figure 4C, D, and Table S4). None of the predicted Nm sites overlap with the 103 other known types of modification on rRNA59 (Figure S3E), although nine of them occurred on 5-mers within the training dataset. Notably, the Nm ratio of rRNAs significantly reduced upon FBL knockdown (Figure 4E, F). Employing our machine learning model, we measured the rRNA Nm ratios in wild-type and three snoRNA knockouts (snR60, snR61, and snR62) yeast strains. The model accurately recapitulated the reported snoRNA-specific deficiency of Nm modification in each snoRNA knockout strain (Figure 4G). Moreover, our method revealed a marked decrease in Nm ratios within Drosophila ribosome RNAs in cells with FBL-knockdown (Figure 4H, I). These results indicated that by combining XGBoost machine learning and the Nanopore technique, we successfully detected the stoichiometric change of known Nm sites in rRNA.

We then used this model to identify Nm modifications on the 100 5-mers throughout all mRNAs. The model identified 26,170 Nm sites from 4,586 genes (Table S4). The methylation ratio at these Nm sites of mRNAs ranged from 0.1 to 1, with an average ratio of 0.30. In contrast, the methylation ratio of Nm sites in rRNA is three-fold higher, with an average ratio of 0.92 (Figure 4J). This observation is reminiscent of an early report that rRNAs have a much longer half-life than mRNA60 and our observation that Nm is positively associated with mRNA stability. The base G is preferentially deposited with Nm, with 40% Nm being on G, much higher than in the mRNA (24%) and training dataset (29%) (Figure S3F). Most of these Nm sites on mRNA were in the exon and 3′ UTR regions (Figure 4K, Figure S3G). Above all, our machine learning model successfully recaptured well-known rRNA Nm sites and revealed more Nm sites with stoichiometry on mRNAs.

FBL promotes widespread Nm on mRNAs with increased RNA stability in PCa cells

We next investigated whether Nm modification at mRNA internal sites in cancer cells is associated with an elevated expression of mRNAs in cancer pathways. To test if FBL regulates the Nm modification on mRNAs in cancer cells, we knocked down FBL and analyzed the effect on mRNA Nm modification. The overall methylation ratios at mRNA Nm sites across the transcriptome were significantly decreased upon the FBL suppression (Figure 5A). KEGG pathway analysis showed that 2′-O-methylated transcripts in C4–2 cells were enriched in PCa-related pathways (Figure S4A). These 2′-O-methylated mRNAs were enriched with the mRNAs showing higher expression levels in C4–2 cells relative to PrEC (Figure S4B). Compared to un-methylated mRNAs, the 2′-O-methylated mRNAs were more likely to be up-regulated in C4–2 cells relative to PrEC (Figure S4C–D). These data indicated that Nm modification is enriched on cancer-related mRNAs upregulated in PCa cells relative to normal cells.

Figure 5. Nm detected on mRNA by machine learning model based on Nanopore direct RNA-seq is downregulated by FBL knockdown.

(A) Boxplot to show the Nm ratio of Nm sites on mRNAs. (B) Scatter plot to show the Nm ratio of individual Nm sites on mRNAs in control and FBL knockdown cells. (C) Average density plot of Nm sites on mRNAs. (D) Venn diagram to show overlap between FBL-binding and 2′-O-methylated mRNAs. (E) The percentage of 2′-O-methylated mRNAs for individual gene groups ranked by mRNA expression level from the lowest to the highest. (F) GSEA shows the relationship between mRNA Nm modification and expression change upon FBL knockdown. (G) Expression change of individual mRNA groups upon FBL knockdown. (H) Boxplot showing mRNA half-life of individual mRNA groups (Hypo: n = 1088, Nm (+): n = 4586, Nm (−): n = 5852). (I) Cumulative fraction of mRNAs plotted against degree of mRNA half-life change upon FBL knockdown. (J) mRNA half-life changes of individual mRNA groups upon FBL knockdown. (K-L) Half-life change (K) and expression change (L) of 2′-O-methylated and unmethylated noncoding RNAs in C4–2 cells (Nm (+): n = 76, Nm (−): n = 480). (M) mRNA half-life of 2′-O-methylated noncoding RNAs in FBL knockdown cells. P values were determined by two-tailed unpaired Wilcoxon’s tests (A, G, H, J-M) and K-S test (I). All presented data were from C4–2 cells. See also Figure S4 and Table S3–4.

We further conducted differential methylation analysis and found that 1568 sites were hypomethylated upon FBL knockdown, while only 285 sites were hyper-methylated (Figure 5B). The average density plot of Nm sites indicated that the decrease of methylated sites happened across the transcripts (Figure 5C). This pattern remained similar for each of the four RNA bases (Figure S3G). Further, we observed a significant overlap between FBL-binding mRNAs and 2′-O-methylated mRNAs in the C4–2 cells (Figure 5D). These results suggested that FBL is required for thousands of Nm sites on mRNAs.

To further understand the role of Nm modification in FBL-mediated mRNA expression regulation, we analyzed the association between mRNA expression changes and Nm changes following FBL knockdown. The genes with higher mRNA expression levels showed higher mRNA Nm ratios (Figure 5E), consistent with a previous report13. We next defined three gene groups, including genes showing hypo-methylated mRNAs upon FBL knockdown, all genes showing Nm modification on mRNAs, and genes showing no detectable Nm on mRNAs. The genes showing Nm on mRNAs tended to be downregulated by FBL knockdown (Figure 5F–G). We found that the genes with hypo-methylated mRNAs had the highest RNA stability, whereas the genes with no detectable Nm on mRNAs had the shortest RNA half-life (Figure 5H).

Furthermore, upon the knockdown of FBL, the hypo-methylated mRNAs showed the most significant decrease in mRNA half-life, whereas unmethylated mRNAs showed the most minor decrease in half-life (Figure 5I–J). These results were further confirmed by profiling RNA half-life using the SLAM-seq method, which does not require the inhibition of transcription (Figure S4E–M). In addition, we also defined the 2′-O-methylated mRNAs based on Nanopore direct RNA-seq data in HEK293T cells and observed similar results as in the C4–2 cells, i.e., the 2′-O-methylated mRNAs overlapped significantly with FBL-binding mRNAs (Figure S4N), showed longer half-life compared to unmethylated mRNAs (Figure S4O–Q), and were more likely to show decreased half-life upon FBL knockdown and NOP56 knockdown (Figure S4R). Intriguingly, the stability of the 2′-O-methylated long noncoding RNAs was notably greater and more sensitive to FBL knockdown compared to their unmethylated counterparts (Figure 5K–M).

To exclude the potential confounding effect of translation efficiency and gene expression level, we performed mRNA half-life analysis between two gene groups specifically selected to have similar translational efficiency change upon FBL knockdown (Figure S5A–F) or expression level (Figure S5L–P), but with one group bearing Nm and the other group showing no detectable Nm. We found the Nm group is still more stable than the unmodified mRNAs. We also checked the distributions of Nm sites at different codon positions in both C4–2 (Figure S5G) and HEK293T (Figure S5J) cells. Interestingly, the number of genes with Nm at the 2nd codon position was less than those with Nm at the 1st and 3rd positions. As previous studies showed that Nm at the 2nd position hinders the translation61,62, it is possible that Nm at the 2nd position was negatively selected by evolutionary pressure or translational stress.

Moreover, mRNAs with Nm at the second codon position were less stable than those with Nm at two other codons in the C4–2 (Figure S5H–I) and HEK293T cells (Figure S5K). This observation is in accordance with the report that Nm at the 2nd codon position hinders translation62, and impaired translation promotes RNA decay63,64. A paired Wilcoxon test of the RNA decay rates revealed 3,176 and 236 genes with decreased and increased RNA half-life upon FBL knockdown, respectively (Figure S5Q). Among them, 33% of the genes showing a decreased RNA half-life were 2′-O-methylated in mRNA, which is a 1.81-fold enrichment compared to random expectation (Figure S5R–S). Remarkably, 28 of these 36 genes with decreased mRNA half-life showed decreased protein levels detected by mass spectrum analysis (Figure S5T). We observed a significant overlap between Nm sites detected by the Nanopore method and the Nm-Mut-seq methods14, with the number of overlapped sites 40 folds greater than expected by chance (Figure S5V–V, Table S5). Meanwhile, no significant overlap was observed between the Nm sites and sites of other detectable modification types on mRNAs (Figure S5W). Together, these data suggest that for most of the Nm sites, their influence on RNA stability is not a confounding effect of RNA expression level, translation efficiency, or other RNA modification types.

FBL-mediated Nm in mRNA is required for the cancer phenotypes of C4–2 cells

Next, we performed RTL-P experiments to validate 10 hyper-methylated sites of eight genes in C4–2 cells (Figure 6A). We confirmed that at least 7 sites showed a decrease of Nm in FBL-knockdown cells (Figure 6B–C). We also observed a reduction in mRNA expression level for these genes upon the FBL knockdown (Figure 6D). Importantly, these 2′-O-methylated mRNAs also showed increased expression in PCa samples compared to normal samples in the TCGA patient datasets (Figure 6E).

Figure 6. FBL expression in PCa cell C4–2 is required for the Nm modification and expression of mRNAs in cancer pathways.

(A) Heatmap to show Nm ratio of 10 Nm sites from Nanopore direct RNA-seq. (B) RTL-P assay to detect the Nm level at 7 Nm sites of mRNAs shown in (A). (C) Densitometric analysis of data from (B) was shown as signal intensity ratio of PCR products at low dNTP (1 μM) over high dNTP (1 mM) level. Methylation levels in control cells were set close to 1. Data represent Mean ± SD from n = 3 biologically independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 is based on two-tailed Student’s t-test. (D) Heat map to show the mRNA expression level of the 8 example genes. (E) Expression change of C4–2 cell 2′-Omethylated mRNAs in PCa and normal patients from the TCGA project dataset. (F) Western blot showing the protein levels of PSMD13 in each group as indicated. (G-H) RTL-P assay to detect the Nm level at two Nm sites of PSMD13 in each group as indicated. (I) Expression of PSMD13 in the TCGA prostate cancer patients grouped based on nodal metastasis status. (J) Disease-free survival of patients with different PSMD13 expression levels in PCa samples from the TCGA dataset. (K) Western blot to show the knockdown efficiency of PSMD13 in C4–2 cells. (L) CellTiter assay to measure the effect of PSMD13 knockdown on cell proliferation. (M-N) Transwell assay to measure the change of cell invasion capability upon PSMD13 knockdown (n = 8), scale bar =100μm. (O-P) Wound Healing assay to determine the change of cell migratory capability upon PSMD13 suppression (n = 6), scale bar =100μm. All presented data were from C4–2 cells except the patient samples from the TCGA database. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 is based on the student’s t-test unless otherwise stated. See also Figure S4–5 and Table S4.

To investigate whether differences in Nm levels in specific mRNAs regulate tumor progression, we performed a focal study on the gene PSMD13 (Figure 6E and Figure S5X). We observed a decrease in PSMD13 protein level following FBL knockdown, which could be rescued by the re-expression of the wild-type, but not a catalytically dead mutant of FBL (referred as FBL-mu)65 (Figure 6F). Consistently, decreases in Nm on PSMD13 mRNA upon FBL knockdown were verified and could be rescued by the overexpression of the wild-type FBL but not the mutant (Figure 6G–H). In addition, elevated expression of PSMD13 is associated with PCa progression (Figure 6I) and poor patient survival in the TCGA cohort51,66 (Figure 6J). Knockdown of PSMD13 decreased cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and migration (Figure 6K–P). These data support the hypothesis that FBL catalyzes Nm on mRNA to increase the expression of PSMD13 and thus plays an oncogenic role in an Nm-dependent manner.

RNA stabilization by Nm is associated with 3′ UTR shortening

To investigate the mechanism by which Nm regulates mRNA stability, we performed a comprehensive analysis to explore mRNA sequence features associated with Nm in C4–2 (Figure 7A–C, S6A–H) and HEK293T cells (Figure S6K–W). These features include 3′ UTR length, miRNA binding sites, ARE element, exon length, intron length, and GC content. We found that the genes of hypo-methylated transcripts upon knockdown of FBL (Hypo) and 2′-O-methylated transcripts (Nm) both showed shorter 3′ UTR lengths compared to the unmethylated transcripts in C4–2 (Figure 7A) and HEK293T cells (S6K). Previous studies have demonstrated that the length of 3′ UTR is negatively correlated with RNA half-life in mice67 and zebrafish68. The mRNAs with longer 3′ UTR tend to have less stability due to an increased chance of being targeted by miRNA69 and some sequence features, such as the AU-rich elements (ARE) in the 3′ UTR70. Consistent with these reports, we found that the methylated transcripts have fewer miRNA target sites and lower ARE scores in C4–2 (Figure 7B–C) and HEK293T cells (S6L–M).

Figure 7. mRNA stabilization by Nm is associated with 3′ UTR shortening.

(A) Cumulative fraction plot of 3′ UTR lengths of individual mRNAs in three groups (Hypo: n = 1088, Nm (+): n = 4586, Nm (−): n = 5852). (B) Number of miRNA target sites in 3′ UTR regions of individual mRNAs in three groups. (C) ARE scores for 3′ UTR regions of individual mRNAs in three groups. (D) Scatter plot to show PDUI (percentage of distal usage index) values of individual mRNAs in control and FBL knockdown conditions. The internal bar plot shows numbers of 3′ UTR lengthening and shortening events induced by FBL knockdown. (E) Venn diagram shows the overlap between genes showing lengthened 3′ UTR upon siFBL and 2′-O-methylated genes under control condition. (F) Number of overlaps observed or expected by chance between genes that show lengthened or shortened 3′ UTR upon siFBL and genes that show 2′-O-methylated mRNAs under control condition. (G) mRNA Nm ratios of individual genes that showed lengthened and shortened 3′ UTR upon FBL knockdown. The ratio of unmethylated sites in siFBL was considered to be 0. (H) Cumulative fraction plot shows mRNA half-life changes of individual gene groups that show lengthened and shortened 3′ UTRs upon FBL knockdown. (I) Genome browser overlay line tracks of RNA-seq read density at 3′ UTR of four example genes. Blue and red curve lines are plotted for control and FBL-knockdown cells, respectively. Blue vertical lines show Nm sites. (J) The percentage of Nm sites overlapping with the binding regions of 10 different RNA binding proteins (RBPs) in HEK293T cells. (K) Scatter plot showing a correlation between the PDUI changes induced by FBL and CPSF depletion in HepG2 cells. (L) RIP-qPCR to detect the change of the binding of CPSF7 to 2′-O-methylated mRNAs upon FBL knockdown. (M) Western blot shows the protein expressions under different conditions. (N) A proposed working model of Nm-dependent regulation of RNA stability. P values were determined by two-tailed unpaired K-S test (A), Wilcoxon test (B, C, G), two-tailed binomial test (D), one-tailed Fisher’s exact test, (F) one-tailed unpaired K-S test (H), Fisher exact test (J), Pearson correlation test (K), and t-test (L). All presented data are from C4–2 cells unless labeled explicitly as from HepG2 cells. Hypo, mRNAs showing hypomethylated Nm sites upon FBL knockdown; Nm (+), mRNAs showing Nm sites and Nm (−), mRNAs showing no detectable Nm sites in C4–2 cells. See also Figure S6–7 and Table S7.

Alternative polyadenylation (APA) is an RNA-processing mechanism that could lead to different 3′ UTR lengths of transcripts derived from the same gene. To detect APA events upon FBL depletion, we performed in-depth RNA-seq in control and FBL-knockdown cells. We found that the FBL knockdown induced a transcriptome-wide increase of distal poly(A) site usage, measured by PDUI (percentage of distal usage index), which suggests a global lengthening of 3′ UTRs (Figure 7D, Table S7). Genes with lengthened 3′ UTRs are significantly enriched with 2′-O-methylated genes, while genes with shortened 3′ UTRs showed no significant overlap (Figure 7E–F, S6I). Additionally, genes with lengthened 3′ UTRs exhibit higher mRNA Nm levels compared to those with shortened UTRs. Upon FBL knockdown, lengthening but not shortening of 3′ UTR is associated with a significant decrease of Nm (Figure 7G). The reduction of mRNA stability upon FBL knockdown is significantly greater for genes with shortened 3′ UTR than for genes with lengthened 3′ UTR (Figure 7H). For instance, hypo-methylation sites, 3′ UTR lengthening, and decreased stability of mRNAs were observed for the genes AKAP8L, PSMD13, CDC6, and NQO2. (Figure 7H–I and Figure S6J).

Based on the findings above, we hypothesized that specific RNA binding proteins (RBPs) might interact with or recognize Nm-modified transcripts, thereby regulating APA. To test this hypothesis, we utilized the CLIPdb database of POSTAR349 to identify RBP-binding regions colocalized with Nm sites regions in HEK293 or HEK293T cells. This analysis revealed a list of 60 RBPs, each with a significant overlap between their binding regions and the Nm sites in mRNAs (Table S7). The top 10 RBPs include the ATXN271, TADRBP72, CPSF773, CPSF674,75, LIN28B76, NUDT2177, FIP1L178, FMR179, DDX3X80 and MOV1081, each with binding regions encompassing more than 10% of the Nm sites (Figure 7J, Figure S7A–B), have previously been reported to involve in regulation of RNA stability or APA. Among them, CPSF7 is reported to promote proximal APA and shorter UTRs73. We further observed a strong positive correlation between differential APA induced by the depletion of CPSF7 and FBL (Figure 7K, S7D), while the depletion of CPSF7 and FBL did not affect the expression of each other82 (Figure S7E). Moreover, the knockdown of FBL impaired the half-life of CPSF7-binding mRNAs (Figure S7C) and the binding of CPSF7 on the Nm-modified transcripts PSMD13, CDC6, AXAPL8 and NQO2 (Figure 7L–M), suggesting that CPSF7 is a potential candidate affecting APA by binding 2′-O-methylated transcripts. At last, we propose a simple working model in which the 2′-O-methylated transcripts tend to have shorter 3′ UTR and thus reduced chance of decay mediated by mechanisms such as miRNAs and AU-rich elements (Figure 7N).

DISCUSSION

Investigating the effect of RNA modification on RNA stability is critical for understanding post-transcriptional regulation in disease83 and developing RNA-based therapeutics84. Previous studies revealed that Nm in the cap of mRNA, 3′-end of siRNA and miRNAs in plants, piRNAs (Piwi-interacting RNAs) in animals protect the RNAs from degradation85. It is also reported that 2′-O-methylation stabilizes specific RNA conformation in vitro86. In this study, we answered whether the internal Nm sites in mRNA regulate cellular mRNA stability. We demonstrated that Nm and FBL-binding transcripts have higher mRNA stability. Taking advantage of the Nanopore technology along with the machine learning strategy, we detected Nm sites and the dynamic changes of Nm in mRNAs across the transcriptome. By profiling of Nm modifications and mRNA half-life in PCa cells, we revealed that elevation of FBL-mediated Nm modifications was associated with increased stability and expression of mRNAs in PCa pathways. Therefore, our finding suggested a post-transcriptional role of FBL in cancer. Transcriptome-wide detection of mRNA Nm modifications in additional cancer types using Nanopore direct RNA-seq will be helpful in uncovering additional role of FBL and Nm.

By investigating how Nm stabilizes mRNA, we found that 2′-O-methylated transcripts have shorter 3′ UTRs compared to unmethylated transcripts. Additionally, knockdown of FBL increased the length of 3′ UTR, and 3′ UTR lengthening is known to decrease mRNA stability68,69. Besides APA, the GC content, length of the 5’ UTR, the CDS, and translation efficiency, can also influence RNA stability. GC content is positively correlated with mRNA half-life87 and affects their subcellular localization. mRNA accumulation in P-bodies is anti-correlated with the GC content of their CDS and 3′ UTR88. Low-GC content of mRNA tends to be in the P-body and be targeted by miRNAs (decay), while high-GC mRNAs could be targeted by RNA binding proteins like YTHDF2 and SMG6 (stable)88. We found that Nm-modified transcripts differ from unmodified transcripts regarding GC content and mRNA length. It will be interesting to investigate how these factors might also contribute to stabilizing Nm-modified transcripts. While our data confirms a link between FBL-mediated Nm modifications and RNA stability, it’s crucial to acknowledge that many FBL-binding transcripts lack Nm modification, suggesting FBL might regulate mRNA in a methylation-independent way.

RNA modifications such as Ψ4, m6A89, and m5C90 are each conferred by multiple writer proteins. Therefore, additional enzymes might also catalyze Nm modifications in mRNA. For example, a 2′-O-Methyltransferase FTSJ3 was reported recently to lead the internal Nm modifications of HIV RNA91. The Spb1, the yeast ortholog of FTSJ3, was also reported for Nm modifications of mRNAs92. A study on new regulators of Nm would advance our understanding of this widespread modification.

Limitations of the Study

Our machine learning model used 107 well-known Nm sites of rRNAs as the positive training data. The model captured over 20,000 Nm sites on mRNAs of more than 4000 genes in the C4–2 cells. However, because the 107 sites only represent a small training dataset, our model covered only 100 of the 1,024 potential 5-mers. This limitation hindered us from capturing all possible Nm modification sites in the transcriptome. Additional methods, e.g., using in vitro transcripts with the incorporation of Nm to cover all 5-mers, will be helpful to improve the machine learning model and capture the entire landscape of Nm sites in the transcriptome. Although Nanopore direct RNA-seq has been employed to detect several different RNA modifications, such as the m6A and m5C, we must admit that false-positive sites are present due to noise signals and the relatively low accuracy of this technology. A newer version of the Nanopore kit with a Q20 (quality score of 20) quality level might improve the capability to detect RNA modifications from single molecular native RNA sequencing.

RNA modifications such as m6A and Ψ were also reported to be associated with APA and thus UTR length93,94. However, the underlying mechanism of these RNA modifications regulating APA is yet unclear. It will be interesting to investigate further the mechanisms in which 2′-O-methylation leads to APA and 3′ UTR shortening. Our experiments and computational analysis suggested that CPSF7 and some other proteins have a strong potential to bind Nm in 3′ UTR to regulate APA. Further confirming the interactions between Nm and these RNA-binding proteins will help understand their role in APA.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Kaifu Chen (Kaifu.Chen@childrens.harvard.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

All sequencing datasets generated in this study have been deposited to Gene Expression Omnibus, with the accession number GSE208837. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the iProX partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD050701. The source of all public datasets and DOI of raw data of gels and blots images used are listed in the key resources table.

The NanoNm software for Nm detection based on Nanopore direct RNA-seq was uploaded to GitHub: https://github.com/YanqiangLi/NanoNm or DOI:10.5281/zenodo.10957952. All computer code of the analyses in this work has been deposited to public repository with DOI:10.5281/zenodo.10835301. The DOIs are also listed in the key resources table.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-FBL | Abcam | Cat#ab5821; RRID:AB2105785 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-NOP56 | Abcam | Cat#ab229497 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-ACTIN | Cell signaling | Cat#3700; RRID: AB_2242334 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-PSMD13 | ABclonal | Cat#A6956 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-CPSF7 | Proteintech | Cat#55195-1-AP; RRID: AB10858797 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 Cell Viability Assay Kit | Promega | Cat#G9241 |

| SLAM-seq kit | LEXOGEN | Cat#062 |

| QuantSeq 3’ mRNA-Seq V2 Library Prep Kits | LEXOGEN | Cat#191 |

| Direct RNA sequencing kit | Oxford Nanopore | Cat# SQK-RNA002 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw nanopore sequence data | This paper | NCBI GEO: GSE208837 |

| RNA-seq for half-life in of HEK293T | This paper | NCBI GEO: GSE208837 |

| RNA-seq for half-life in C4-2 cell | This paper | NCBI GEO: GSE208837 |

| 3’ mRNA SLAM-RNA-seq for half-life in C4-2 | This paper | NCBI GEO: GSE208837 |

| RIP-seq in the C4-2 cell | This paper | NCBI GEO: GSE208837 |

| RNA-seq in C4-2 and PrEC cell | Gao et.al52 | NCBI GEO: GSE197495 |

| RNA-seq of FBL KO in HepG2 | ENCODE Project95 | NCBI GEO: GSE177747 |

| RNA-seq of CPSF7 KO in HepG2 | ENCODE Project95 | NCBI GEO: GSE219714 |

| Raw nanopore sequence data of HepG2 | Tavakoli et.al96 | NCBI GEO: SRR24298526 |

| Raw nanopore sequence data of HeLa | Tavakoli et.al96 | NCBI GEO: SRR24298526 |

| Raw nanopore sequence data of Yeast | Begik et.al42 | ENA database: ERA3183105 |

| Raw nanopore sequence data of Drosophila | Sklias et.al97 | NCBI GEO: PRJEB45722 |

| Raw data of gels and blots | This paper | https://doi.org/10.17632/yshp7typsf.1 |

| Raw data of proteomics | This paper | iProX: PXD050701 |

| Codes for Nm detection | This paper |

https://github.com/YanqiangLi/NanoNm

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10957952 |

| R scripts for plot | This paper | https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10835301 |

| CLIP-seq database of RNA binding proteins | Zhao et.al49 | http://postar.ncrnalab.org |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human: C4-2 cell line | Dr. Leland W. Chung | N/A |

| Human: HEK293T cells | ATCC | Cat#CRL-3216 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| GCTGTCAGGATTGCGAGAGAT siRNA targeting 3’-UTR of endogenous FBL mRNA used for rescue assay | Zhou et.al65 | N/A |

| RT, RIP and RTL-PCR primers | See Table S6 | N/A |

| siRNA sequences | See Table S6 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| tombo v1.5.1 | Oxford Nanopore | https://github.com/nanoporetech/tombo |

| guppy v3.6.1 | Oxford Nanopore | https://nanoporetech.com/ |

| ont_fast5_api 3.1.6 | Oxford Nanopore | https://github.com/nanoporetech/ont_fast5_api |

| Minimap2 version 2.22-r1101 | Li et.al98 | https://github.com/lh3/minimap2 |

| Tophat 2.1.0 | Kim et.al99 | https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat |

| edgeR | Chen et.al100 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edqeR.html |

| htseq-count | Putri et.al101 | https://htseq.readthedocs.io/en/release_0.11.1/count.html |

| REDITs | Tran et.al102 | https://github.com/gxiaolab/REDITs |

| fastp | Chen et.al103 | https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp |

| SLAMdunk | Neumann et.al104 | https://github.com/t-neumann/slamdunk |

| SLAM-seq analysis | Loedige et.al105 | https://github.com/melonheader/HLEB |

| Homer annotePeaks.pl | Heinz et.al106 | http://homer.ucsd.edu |

| AREscore | Spasic et.al107 | http://arescore.dkfz.de/arescore.pl. |

| GSEA Java software (v4.0.3) | Subramanian et.al108 | https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb |

| clusterProfiler (v4.0.5) | Wu et.al109 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html |

| GeneOverlap | Shen et.al110 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/GeneOverlap.html |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

The human PCa cell line C4–2 was a gift from Dr. Leland W. Chung at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). HEK293T cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Both cell lines were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere and were authenticated and routinely screened for Mycoplasma.

METHOD DETAILS

Antibodies and reagents

The antibodies used in this study are listed in the key resources table.

Transfection of siRNA

All the siRNAs used in this study were purchased from Thermo Fisher (siFBL-1: s4820, siFBL-2: s4821; siNOP56–1: s20641, siNOP56–2: s20642, siPSMD13–1: s229818, siPSMD13–2: s229819). Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) was utilized for siRNA transfection per the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were collected at 3 days post-transfection for further use. If the number of siRNA was not indicated in the study, it should represent siRNA-1.

RNA extraction and Real-time (RT)- qPCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA was then synthesized using the Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo). The obtained cDNA samples were amplified using Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) in a QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-time PCR system (GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers used for qPCR analysis were summarized in Table S6. The relative RNA level was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with the Ct values normalized using GAPDH as an internal control.

Reverse Transcription at Low dNTP concentrations followed by PCR (RTL-P) method to detect Nm levels in mRNA

To validate the 2′-O methylation in mRNA, we extracted total RNA from control, FBL-knockdown, and NOP56-knockdown cells using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using specific reverse primers targeting mRNA sequences upstream to one methylation site in the presence of either a low level (1 μM) or a high level (1 mM) of dNTP. The RT reaction mixture contains 200 ng RNA, 200 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega), 10 mM RT primers, 0.5 U RNase Inhibitor (Promega), and deoxynucleotide (dNTP) (low/high, Invitrogen). The obtained cDNA was subjected to two separate amplification reactions using two pairs of primers targeting upstream and downstream of the methylation site, respectively. The cartoon in the top left subpanel of Figure 2G indicates the locations of primers used for RTL-P assay; m: Nm site; Um: upstream of Nm site; Dm: downstream of Nm site; F: forward primer; R: reverse primer; RT: Reverse transcription. The PCR mixture contains 10 μL amfisure PCR Master Mix (GenDEPOT), 2 μL cDNA and 10 mM PCR primers. The PCR products were then separated on 1% agarose gels and visualized by a Bio-rad imaging system. DNA band signal intensities were analyzed using ImageJ software. The methylation ratio of each group was determined from the densities of PCR bands obtained using high and low dNTP concentrations. The RT and PCR primers designed for RTL-P assay are listed in Table S6.

Total RNA extraction and quality assessment

Total RNA was extracted using RNAprep Pure Kit (polysaccharides and polyphenolics-rich) and treated with DNase I to remove DNA. Firstly, the quality of total RNAs was detected using 1% agarose electrophoresis, and no RNA degradation was observed. Then, the OD260/280 for all the samples was at 2.12–2.15 using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Finally, the RIN value for all the samples was above 9.0 using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer in combination with RNA Analysis Kits.

Western blot

Cell lysates were prepared and denatured by adding 4× loading buffer (Bio-Rad) and incubating at 95°C for 10 minutes. Subsequently, the protein samples were separated through SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and semi-dry transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). After blocking for 30 minutes in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST) containing 5% nonfat milk, the membranes were subjected to immunoblotting by incubating with primary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature. Following this, the membranes were washed and incubated with goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG (H + L)-HRP secondary antibody (GenDEPOT) at a 1:5000 dilution for 1 hour. The signals were developed using a western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad) and captured with a Bio-Rad imaging system. A list of primary antibodies used in this study can be found in the STAR method.

FBL rescue experiments

FBL rescue experiments were conducted in C4–2 cells following Zhou et.al65. Initially, lentivirus expressing doxycycline-inducible siCtrl and siFBL (targeting the 3’ UTR of endogenous FBL mRNA) were used to infect C4–2 cells. These inducible knockdown cells were then utilized for FBL experiments. The empty vector, wild-type FBL, or mutant FBL, into the inducible FBL knockdown cells was delivered through lentivirus infection, followed by the induction of FBL knockdown with 100 ng/mL doxycycline for 3 days.

Cell Viability Assay

Control or PSMD13-deficient C4–2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 10^3 cells/well and incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. At the designated time points, the culture medium was aspirated, and 100 μL of CellTiter-Glo 2.0 solution (Promega) was added to each well. The plates were then placed on an orbital shaker at 37°C for 10 minutes to induce cell lysis, and bioluminescence was measured using a Tecan plate reader.

Wound healing assay

Control or PSMD13-deficient C4–2 cells were cultured in 35 mm dishes with 3-well Culture-Insert (Ibidi) till grown to 80% confluency. After carefully removing the inserts, the dishes were replenished with serum-free 1640 medium and sustained in a humidified environment at 37°C. Microscopic images were captured at the 0-hour and 30-hour marks, and the extent of cell migration was quantified by ImageJ software.

Boyden chamber invasion assay

To assess the invasiveness of C4–2 cells undergoing PSMD13 suppression, we employed Boyden chamber assays using Transwell inserts (Millipore) coated with Matrigel (Corning). In brief, the upper surface of polycarbonate membranes (8.0-μm pore size) within the Transwell chambers was coated with a diluted Matrigel (1:20) in 1640 medium. Subsequently, cells (3 × 10^4) suspended in 300 μL of serum-free 1640 medium were added to the upper compartments of the chambers, while the lower compartments were filled with 800 μL of 1640 medium containing 10% FBS. After 24 hours, cells that had migrated from Matrigel to the lower surface of the filters were fixed with methanol, stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Sigma), and subjected to microscopic examination. The number of invasive cells was determined as the average count from 6 randomly selected fields per filter.

Nanopore direct RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing

For library preparation, the total RNA was extracted from control and FBL-deficient C4–2 cells using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen), followed by mRNA isolation using PolyATtract® mRNA Isolation System (Promega). The mRNA concentration was measured by Qubit RNA HS assay kit (ThermoFisher, Q32855), and the quality was confirmed by Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA Pico assay chip. Then, the mRNA was subjected to library construction using an Oxford Nanopore direct RNA sequencing kit (SQK-RNA002) according to the manufacturer’s manual. 500 ng of mRNA was first annealed, ligated to RT adapter, and then reverse-transcribed to form DNA-RNA hybrid products. Then, the RNA adapter was ligated to the products and was ready for sequencer loading. The resulting library was sequenced on an R9.4.1 flow cell (FLO-MIN106D) using a MinION sequencer, and FAST5 raw sequencing data was obtained in a real-time manner.

Training the machine learning model by rRNA Nm data

The Nanopore dataset of rRNA and unmodified in vitro transcripts (IVT) were downloaded from the SRA database by accession number SRP16602043. Each fast5 file was divided into single fast5 files using the software multi_to_single_fast5(version 3.1.6). Base-calling was performed using Guppy (version 3.6.1+249406c). Then, the re-squiggle algorithm in Tombo (version 1.5.1) was used to correct the raw signal based on reference transcripts. For the detection of Nm based on Nanopore direct RNA-seq, we developed a machine-learning model on top of the Nanom6A42, developed initially to detect m6A. At first, the rRNA reads were mapped to the reference of human rRNA. We extracted training features, including the median, standard deviation, mean, and dwell time of the Nanopore signal for the k-mer around each Nm site in the rRNA. On the other hand, we also extracted these features of the same k-mer from the IVT reads of mRNA. Then, we trained an XGBoost model by dividing the features into the training and testing sets with a ratio of 4:1 for cross-validation. The XGBoost model was constructed using the machine learning library Scikit-learn. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the ROC (AUROC) were used to evaluate the performance of the model.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)-qPCR

The RIP experiment was conducted using the EZ-Magna RIP kit (Millipore) following the User’s Guide. In brief, control or FBL-deficient C4–2 cells were lysed in RIP lysis buffer and incubated with anti-CPSF7 antibody and protein A/G magnetic beads mixture at 4 °C overnight to enrich the RNA-bound CPSF7 proteins. The CPSF7-associated RNAs were extracted by Proteinase K digestion, followed by purification and reverse transcription into cDNA. Then, the qPCR assay was performed to measure the %Input of selected mRNA candidates in each group using the primers shown in Supplementary Table 6.

Proteomics

Proteomics services were performed by the Northwestern Proteomics Core Facility. We lysed cells and measured protein concentration by BCA, then used 200 ug of total protein from each of the 6 samples (two controls and four FBL knock down) for the subsequent processes. The proteins were purified by acetone/TCA precipitation, reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin according to our optimized protocol. Digested peptides were desalted on C18 columns then subject to mass spec analysis. We searched the data against a human database using MaxQuant search engine and then performed label-free quantification (LFQ) based on the MS1 peptide intensity.

Functional enrichment analysis of gene groups

KEGG functional enrichment analysis was performed using the R package clusterProfiler (v4.0.5)109. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis was performed using the GSEA Java software (v4.0.3)108. Overlap analysis between two gene sets was performed using the R package GeneOverlap110.

Analyze the overlap of Nm sites with reported Nm sites and other RNA modification sites

RNA modification sites, including the m6A111, A to I editing112, Ψ113, m5C114, m7G9, and Nm14 sites, from HEK293T cells with single base resolution were collected from the associated literature. These sites in different human genome versions were lifted to the same genome version, hg38, using LiftOver in the UCSC genome browser: https://genome.ucsc.edu.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

RNA half-life calculation

After RNA-seq, the reads were mapped to the genome hg38 using tophat (version 2.1.1)99 with default parameter values and UCSC-known genes as reference. Read counts of each gene were computed by htseq-count (version 0.11.2)115. RNA half-life of the HEK293T cell and C4–2 cells was calculated as described before116. The RNA levels were first normalized to RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase Million). To reduce the noise due to genes that showed a higher expression level after inhibition of transcription, we scaled the RPKM values based on the expression levels of the top 10 genes which were most stable between time points, so that these genes will have no change of expression between time points after the normalization. The RNA degradation rate kdecay was defined as the mean values of ratio from RPKM at time 0 over the RPKM value at each other time point (0 hour, 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours). After that the pseudo-mRNA half-life t1/2 was calculated as ln2/kdecay.

SLAM-seq to measure mRNA half-life

Following the manufacturer’s protocol, the mRNA degradation kinetics was measured using SLAM-seq Kinetics Kit: Catabolic Kinetics Module (LEXOGEN). In general, control or FBL-deficient C4–2 cells were cultivated in 1640 medium containing 100 μM 4-thiouridine (S4U) for a continuous 24-hour duration. Subsequently, the S4U-containing medium was exchanged by medium with an excess (10 mM) of unmodified uridine (U), and cell samples were collected at specific time points. The reference point for these time points was set at 0 hour, corresponding to the moment of S4U removal. RNA isolation was performed on all collected samples by Trizol (Thermo), and the 4-thiol groups present on S4U-labeled transcripts were alkylated with iodoacteamide. The libraries were generated from 70–200 ng of input RNA using QuantSeq 3’ mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit (LEXOGEN), followed by shipment to Admera Health for sequencing.

To estimate mRNA half-lives, we followed a published SLAM-seq protocol. Initially, raw reads in fastq files underwent quality checking and trimming using fastp103. Subsequently, these reads were processed with slamdunk104. For mRNA half-life estimation, half-life values per gene were averaged over three replicates per condition, following the pipeline from https://github.com/melonheader/HLEB105. We also calculated a filtered version that averaged only over data from those replicates where the calculated pseudo-R2 values were >0.95 (providing evidence for good model fits) and considered those values as ‘stringently’ filtered where at least 2 replicates remained after filtering and where the standard deviation of the considered half-life values less than 1.

Comparison of mRNA half-life of two transcript groups with similar expression levels and translation efficiency change

To exclude the confounding effect of RNA expression and translation efficiency on RNA stability. We combined the Nm transcripts and unmodified transcripts into a pool. The genes were ranked by their expression levels or translation efficiency changes and then segmented into 20 equal groups. From each group, an equal number of Nm-modified and unmodified mRNAs were randomly selected to form a subset of Nm transcripts and a subset of unmodified mRNAs to evaluate their half-lives as we described before116.

Detection of Nm based on Nanopore direct RNA-seq data

After base-calling using guppy_basecaller (version 3.6.1), the Nanopore direct RNA-seq reads with quality values greater than 7 were aligned to the human genome version hg38 (GRCh38.p13 from the GENCODE database) using Minimap2 (version 2.22-r1101) with parameters “--secondary=no -ax splice -uf -k14”. The re-squiggle algorithm in Tombo version 1.5.1 was used to correct sequence errors based on reference transcripts downloaded from: https://www.gencodegenes.org/human. The data were then subjected to the machine learning model to detect Nm. A base found to be modified in at least 5 transcripts was identified as a modified Nm site. Differentially methylated sites between normal and knockdown cells were calculated by the R package REDITs (https://github.com/gxiaolab/REDITs)102. The average density of the Nm site across the transcript body was plotted using the Guitar R/Bioconductor package117. A similar method is applied to the Nm detection of rRNA in yeast. The Nanopore direct RNA-seq data of rRNA in WT, snR60, snR61, and snR62 strains of yeast42, human HepG2 and HeLa cell96, and Drosophila cells97 were downloaded from the ERA3183105, PRJNA777450 and PRJEB45722 of the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database and GEO database, respectively. After base-calling, mapping, and feature extraction, our model trained with human rRNA was applied to detect the Nm in these samples.

FBL RIP-seq and analysis

The FBL-binding transcripts in HEK293T cells were obtained from the database of CLIP-seq: http://postar.ncrnalab.org. The RIP experiment in C4–2 cells was performed using the EZ-Magna RIP kit (Millipore), following the procedure provided by the manufacturer. C4–2 cells were lysed in RIP lysis buffer and incubated with FBL antibody-magnetic beads mixture at 4 °C overnight to enrich RNA binding protein. The RNA that bound to FBL protein was collected by Proteinase K digestion, followed by purification and precipitation. For high-throughput sequencing, input and RIP-ed RNA samples were shipped to BGI for library preparation and sequencing using the DNBseq platform. After mapping to the genome hg38 using tophat (version 2.1.1)99 1 with default parameter values and UCSC known genes as a reference, we used the software piranha118 to analyze the RIP-seq data with default parameters. The Homer annotatePeaks.pl script was used to annotate peaks from the RIP-seq data106. We used a P-value cutoff of 0.01 to define FBL-binding RNAs in the C4–2 cells.

Analysis of sequence features and APA of 2′-O-Methylated transcripts.

To analyze the mRNA features of 2′-O-Methylated transcripts, we used mRNA features including length of UTRs, CDS, and exon transcripts in a public dataset22. We calculated the ARE score of 3′ UTR by the software AREscore107 and downloaded miRNA binding sites of UTRs and CDS from the miRWalk database119. We used Dapars2 to perform APA analysis with the default parameters120,121. We considered a gene to be regulated by FBL if its PDUI values from both replicates were lower or greater in FBL-knockdown cells than in the control cells and if the difference in average PDUI values was larger than 0.1.

In silico screening of RNA binding proteins co-localized with Nm

CLIP-seq database of RNA binding proteins in HEK293/HEK293T cells were retrieved from the POSTAR3 database49, and the overlapped regions of each file were merged using “bedtools merge”. These regions were overlapped with Nm sites in HEK293T cells. Fisher exact test was performed to determine the significance of the overlap between the binding regions of the RNA binding protein and the Nm sites. An odd ratio of more than 1.5 and an adjusted P-value of less than 0.01 were cutoffs to define a significant overlap.

Statistics

The statistical details of experiments can be found in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Table S2. List of FBL-binding mRNA in C4–2 cell samples, related to Figure 3.

Table S3. mRNA half-life of each gene in each C4–2 cell sample from the actD inhibition method and the SLAM-seq method, related to Figure S4–5.

Table S4. Nanopore direct RNA-seq data in C4–2 cell samples, including a summary of the dataset, a list of Nm sites detected on rRNAs and mRNAs based on Nanopore direct RNA-seq in individual C4–2 cell samples, and gene expression levels determined based on Nanopore direct RNA-seq data, related to Figure 4–6.

Table S5. List of Nm sites detected in HEK293T, HeLa, and HepG2 cells by Nanopore direct RNA-seq data, related to Figure S4–5.

Table S7. PDUI changes of individual genes between control and FBL knockdown cells and in silico screening of RNA binding proteins co-localized with Nm, related to Figure 7.

Highlights:

Widespread 2′-O-methylation (Nm) at mRNA internal sites promotes mRNA stability

De novo detection and measurement of Nm by Nanopore RNA-seq and machine learning

FBL deficiency decreased Nm, stability, and expression level of mRNAs in PCa

Nm is linked to alternative polyadenylation, which leads to 3’ UTR shortening

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project is supported in part by NIH grants R01GM125632, R01GM138407, R01HL148338, R01HL133254 to K.C., R01CA208257 and R01CA256741 to Q.C., R01HL155632 to L.Z. and U.S. Department of Defense grants W81XWH-17-1-0357, W81XWH-19-1-0563 and W81XWH-20-1-0504 to Q.C. and HT9425-23-1-0661 to Y.Y., Prostate SPORE P50CA180995 Development Research Program and the Polsky Urologic Cancer Institute of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University at Northwestern Memorial Hospital to Q.C. The Nanopore RNA-seq was done at Northwestern University NUseq facility core with the support of NIH Grant (1S10OD025120). Proteomics services were performed by the Northwestern Proteomics Core Facility, generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, instrumentation award (S10OD025194) from NIH Office of Director, and the National Resource for Translational and Developmental Proteomics supported by P41 GM108569.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, and He C (2017). Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell 169, 1187–1200. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boccaletto P, Stefaniak F, Ray A, Cappannini A, Mukherjee S, Purta E, Kurkowska M, Shirvanizadeh N, Destefanis E, Groza P, et al. (2022). MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2021 update. Nucleic Acids Res 50, D231–D235. 10.1093/nar/gkab1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, Cesarkas K, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Kupiec M, et al. (2012). Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485, 201–206. 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlile TM, Rojas-Duran MF, Zinshteyn B, Shin H, Bartoli KM, and Gilbert WV (2014). Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 515, 143–146. 10.1038/nature13802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelheit S, Schwartz S, Mumbach MR, Wurtzel O, and Sorek R (2013). Transcriptome-wide mapping of 5-methylcytidine RNA modifications in bacteria, archaea, and yeast reveals m5C within archaeal mRNAs. PLoS Genet 9, e1003602. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahn JH, Lee JH, Li G, Greer C, Peng G, and Xiao X (2012). Accurate identification of A-to-I RNA editing in human by transcriptome sequencing. Genome Res 22, 142–150. 10.1101/gr.124107.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safra M, Sas-Chen A, Nir R, Winkler R, Nachshon A, Bar-Yaacov D, Erlacher M, Rossmanith W, Stern-Ginossar N, and Schwartz S (2017). The m1A landscape on cytosolic and mitochondrial mRNA at single-base resolution. Nature 551, 251–255. 10.1038/nature24456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Xiong X, Zhang M, Wang K, Chen Y, Zhou J, Mao Y, Lv J, Yi D, Chen XW, et al. (2017). Base-Resolution Mapping Reveals Distinct m(1)A Methylome in Nuclear- and Mitochondrial-Encoded Transcripts. Mol Cell 68, 993–1005 e1009. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang LS, Liu C, Ma H, Dai Q, Sun HL, Luo G, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Hu L, Dong X, and He C (2019). Transcriptome-wide Mapping of Internal N(7)-Methylguanosine Methylome in Mammalian mRNA. Mol Cell 74, 1304–1316 e1308. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arango D, Sturgill D, Alhusaini N, Dillman AA, Sweet TJ, Hanson G, Hosogane M, Sinclair WR, Nanan KK, Mandler MD, et al. (2018). Acetylation of Cytidine in mRNA Promotes Translation Efficiency. Cell 175, 1872–1886 e1824. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sas-Chen A, Thomas JM, Matzov D, Taoka M, Nance KD, Nir R, Bryson KM, Shachar R, Liman GLS, Burkhart BW, et al. (2020). Dynamic RNA acetylation revealed by quantitative cross-evolutionary mapping. Nature 583, 638–643. 10.1038/s41586-020-2418-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayadi L, Galvanin A, Pichot F, Marchand V, and Motorin Y (2019). RNA ribose methylation (2′-O-methylation): Occurrence, biosynthesis and biological functions. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 1862, 253–269. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dai Q, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Han D, Kol N, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, Dominissini D, and He C (2017). Nm-seq maps 2′-O-methylation sites in human mRNA with base precision. Nat Methods 14, 695–698. 10.1038/nmeth.4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Zhang LS, Ye C, Zhou H, Liu B, Gao B, Deng Z, Zhao C, He C, and Dickinson BC (2023). Nm-Mut-seq: a base-resolution quantitative method for mapping transcriptome-wide 2′-O-methylation. Cell Res 33, 727–730. 10.1038/s41422-023-00836-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang P, Huang J, Zheng W, Chen L, Liu S, Liu A, Ye J, Zhou J, Chen Z, Huang Q, et al. (2023). Single-base resolution mapping of 2′-O-methylation sites by an exoribonuclease-enriched chemical method. Science China. Life sciences 66, 800–818. 10.1007/s11427-022-2210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott BA, Ho HT, Ranganathan SV, Vangaveti S, Ilkayeva O, Abou Assi H, Choi AK, Agris PF, and Holley CL (2019). Modification of messenger RNA by 2′-O-methylation regulates gene expression in vivo. Nat Commun 10, 3401. 10.1038/s41467-019-11375-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi J, Indrisiunaite G, DeMirci H, Ieong KW, Wang J, Petrov A, Prabhakar A, Rechavi G, Dominissini D, He C, et al. (2018). 2′-O-methylation in mRNA disrupts tRNA decoding during translation elongation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25, 208–216. 10.1038/s41594-018-0030-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, Hon GC, Yue Y, Han D, Fu Y, Parisien M, Dai Q, Jia G, et al. (2014). N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505, 117–120. 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, Li A, Sun BF, Yang Y, Han YN, Yuan X, Chen RX, Wei WS, Liu Y, Gao CC, et al. (2019). 5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs. Nat Cell Biol 21, 978–990. 10.1038/s41556-019-0361-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Wang L, Han X, Yang WL, Zhang M, Ma HL, Sun BF, Li A, Xia J, Chen J, et al. (2019). RNA 5-Methylcytosine Facilitates the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition by Preventing Maternal mRNA Decay. Mol Cell 75, 1188–1202 e1111. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz S, Bernstein DA, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Herbst RH, Leon-Ricardo BX, Engreitz JM, Guttman M, Satija R, Lander ES, et al. (2014). Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell 159, 148–162. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal V, and Kelley DR (2022). The genetic and biochemical determinants of mRNA degradation rates in mammals. Genome Biol 23, 245. 10.1186/s13059-022-02811-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcel V, Ghayad SE, Belin S, Therizols G, Morel AP, Solano-Gonzalez E, Vendrell JA, Hacot S, Mertani HC, Albaret MA, et al. (2013). p53 acts as a safeguard of translational control by regulating fibrillarin and rRNA methylation in cancer. Cancer Cell 24, 318–330. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi Y, Li Y, Meng Q, Li Q, Li F, Lu B, Shen J, Fazli L, Zhao D, Li C, et al. (2021). A PRC2-independent function for EZH2 in regulating rRNA 2′-O methylation and IRES-dependent translation. Nat Cell Biol 23, 341–354. 10.1038/s41556-021-00653-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erales J, Marchand V, Panthu B, Gillot S, Belin S, Ghayad SE, Garcia M, Laforets F, Marcel V, Baudin-Baillieu A, et al. (2017). Evidence for rRNA 2′-O-methylation plasticity: Control of intrinsic translational capabilities of human ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 12934–12939. 10.1073/pnas.1707674114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiss-Laszlo Z, Henry Y, Bachellerie JP, Caizergues-Ferrer M, and Kiss T (1996). Site-specific ribose methylation of preribosomal RNA: a novel function for small nucleolar RNAs. Cell 85, 1077–1088. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bratkovic T, Bozic J, and Rogelj B (2020). Functional diversity of small nucleolar RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 48, 1627–1651. 10.1093/nar/gkz1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tessarz P, Santos-Rosa H, Robson SC, Sylvestersen KB, Nelson CJ, Nielsen ML, and Kouzarides T (2014). Glutamine methylation in histone H2A is an RNA-polymerase-I-dedicated modification. Nature 505, 564–568. 10.1038/nature12819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe-Susaki K, Takada H, Enomoto K, Miwata K, Ishimine H, Intoh A, Ohtaka M, Nakanishi M, Sugino H, Asashima M, and Kurisaki A (2014). Biosynthesis of ribosomal RNA in nucleoli regulates pluripotency and differentiation ability of pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 32, 3099–3111. 10.1002/stem.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouffard S, Dambroise E, Brombin A, Lempereur S, Hatin I, Simion M, Corre R, Bourrat F, Joly JS, and Jamen F (2018). Fibrillarin is essential for S-phase progression and neuronal differentiation in zebrafish dorsal midbrain and retina. Dev Biol 437, 1–16. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delhermite J, Tafforeau L, Sharma S, Marchand V, Wacheul L, Lattuca R, Desiderio S, Motorin Y, Bellefroid E, and Lafontaine DLJ (2022). Systematic mapping of rRNA 2′-O methylation during frog development and involvement of the methyltransferase Fibrillarin in eye and craniofacial development in Xenopus laevis. PLoS Genet 18, e1010012. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su H, Xu T, Ganapathy S, Shadfan M, Long M, Huang TH, Thompson I, and Yuan ZM (2014). Elevated snoRNA biogenesis is essential in breast cancer. Oncogene 33, 1348–1358. 10.1038/onc.2013.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, Begik O, Lucas MC, Ramirez JM, Mason CE, Wiener D, Schwartz S, Mattick JS, Smith MA, and Novoa EM (2019). Accurate detection of m(6)A RNA modifications in native RNA sequences. Nat Commun 10, 4079. 10.1038/s41467-019-11713-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garalde DR, Snell EA, Jachimowicz D, Sipos B, Lloyd JH, Bruce M, Pantic N, Admassu T, James P, Warland A, et al. (2018). Highly parallel direct RNA sequencing on an array of nanopores. Nat Methods 15, 201–206. 10.1038/nmeth.4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]