Abstract

Background and Objectives

Motor outcomes after stroke relate to corticospinal tract (CST) damage. The brain leverages surviving neural pathways to compensate for CST damage and mediate motor recovery. Thus, concurrent age-related damage from white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) might affect neurologic capacity for recovery after CST injury. The role of WMHs in post-stroke motor outcomes is unclear. In this study, we evaluated whether WMHs modulate the relationship between CST damage and post-stroke motor outcomes.

Methods

We used data from the multisite ENIGMA Stroke Recovery Working Group with T1 and T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging. CST damage was indexed with weighted CST lesion load (CST-LL). WMH volumes were extracted with Freesurfer's SAMSEG. Mixed-effects beta-regression models were fit to test the impact of CST-LL, WMH volume, and their interaction on motor impairment, controlling for age, days after stroke, and stroke volume.

Results

A total of 223 individuals were included. WMH volume related to motor impairment above and beyond CST-LL (β = 0.178, 95% CI 0.025–0.331, p = 0.022). Relationships varied by WMH severity (mild vs moderate-severe). In individuals with mild WMHs, motor impairment related to CST-LL (β = 0.888, 95% CI 0.604–1.172, p < 0.001) with a CST-LL × WMH interaction (β = −0.211, 95% CI −0.340 to −0.026, p = 0.026). In individuals with moderate-severe WMHs, motor impairment related to WMH volume (β = 0.299, 95% CI 0.008–0.590, p = 0.044), but did not significantly relate to CST-LL or a CST-LL × WMH interaction.

Discussion

WMHs relate to motor outcomes after stroke and modify relationships between motor impairment and CST damage. WMH-related damage may be under-recognized in stroke research as a factor contributing to variability in motor outcomes. Our findings emphasize the importance of brain structural reserve in motor outcomes after brain injury.

Introduction

Upper extremity motor impairment is one of the most common consequences of stroke1 and typically results in long-term disability.2 The degree of damage to the corticospinal tract (CST) relates strongly to motor impairment after stroke,3,4 indicating a primary insult to the motor system. However, motor recovery after stroke is variable even after accounting for CST damage.5 Recovery after stroke is likely mediated by compensation of surviving neural substrate.6 This suggests that the integrity of structures beyond the CST might be prognostic of motor recovery7,8 because overall brain health may be important in explaining why 2 individuals with similar stroke lesions can experience very different trajectories of recovery.9

White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) of presumed vascular origin are the most common form of age-related cerebrovascular damage.10 They are present in more than half of people older than 60 years.11 Individuals with WMHs are more likely to experience a stroke12 in part because of common cardiometabolic risk factors between WMHs and stroke.13 There is growing evidence that WMHs can also affect functional outcomes after stroke.14 The relationship between WMHs and post-stroke cognitive impairment has been well established14; however, there have been few investigations of the specific impact of WMHs on motor outcomes after stroke. WMHs modulate relationships between stroke lesion volume and overall functional outcome.15,16 Motor outcomes after stroke may similarly be modulated by concurrent WMHs because of the widespread impacts of WMHs on cerebral networks,17,18 which may create preexisting damage in compensatory pathways and, therefore, decrease the brain's capacity for motor recovery.

We tested whether the relationship between post-stroke motor impairment and CST damage is affected by concurrent WMH damage, controlling for age, time after stroke, and stroke lesion volume. We hypothesized that the relationship between motor impairment and CST damage would be attenuated in individuals with higher WMH volumes, indicating a greater influence of concurrent WMHs on motor outcomes after stroke.

Methods

Study Data

This study used cross-sectional multisite data from the ENIGMA Stroke Recovery Working Group.19 The ENIGMA Stroke Recovery Working Group is an international consortium that pools and harmonizes retrospective stroke data for large-scale analyses of brain-behavior relationships after stroke. The core ENIGMA Center is based at the University of Southern California. To be eligible for inclusion in the ENIGMA Stroke Recovery Database, contributing sites need to provide T1-weighted anatomic scans and at least 1 behavioral measure of post-stroke outcomes for their cohort. Data for this analysis were frozen on March 17, 2023. The inclusion criteria for selection of participants from the ENIGMA database for this analysis were (1) individuals with stroke where imaging and behavioral assessments occurred >7 days after stroke, (2) availability of T1-weighted MRI scans to index stroke lesions and either fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) or T2-weighted scans to index WMHs, and (3) availability of a sensorimotor outcome measure (e.g., Fugl-Meyer Assessment, Action Research Arm Test, and Wolf Motor Function Test). We extracted the following demographic information: age, sex, and days after stroke. This study comprised a cohort of individuals in the subacute and chronic phases of recovery after stroke. Stroke chronicity was defined as early subacute phase of recovery >7 and ≤90 days after stroke, late subacute phase >90 and ≤180 days after stroke, and chronic phase >180 days after stroke.20

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Ethics approval was obtained from the local research ethics board of each contributing site. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by members of the ENIGMA Stroke Recovery Working Group.

Motor Impairment Score

Sensorimotor outcome measures were harmonized across study cohorts with a motor outcome score, consistent with previous ENIGMA publications.9,21 Harmonized motor outcome scores were calculated as a proportion of the total possible score for each sensorimotor scale. In this analysis, 0% indicates no sensorimotor impairment and 100% indicates maximum sensorimotor impairment. For example, if someone scored a 33 on the Fugl-Meyer Upper-Extremity Assessment (where the maximum value is 66, and higher numbers indicate less motor impairment), their harmonized motor score would be 50%. For simplicity, we refer to this harmonized score as “motor impairment.”

Lesion Analysis

MRI processing was conducted with tools from FSL (v.6.0.5) and Freesurfer (v.7.2). Stroke lesions were manually traced on T1-weighted scans by trained researchers following established ENIGMA lesion tracing protocols.22,23 WMH damage was operationalized by whole-brain WMH volume. WMH volumes were segmented with Freesurfer's SAMSEG, which we previously established has robust performance in multisite data from individuals with stroke.24 Linearly co-registered T1 and FLAIR/T2 scans were used as inputs into SAMSEG, and a 0.1 probability threshold was applied to tissue segmentation. We subtracted stroke lesion masks from segmented WMHs to prevent any misclassification of stroke lesions as WMHs. Fazekas scores were visually rated for each scan by a neuroradiologist.25

CST damage was operationalized by CST lesion load (CST-LL), an index of the degree of overlap between the CST and the stroke lesion.3 CST-LL is a biomarker of post-stroke motor outcomes.4 We calculated weighted CST-LL from stroke lesion masks. T1 images were nonlinearly registered to MNI152 space using FSL's FNIRT.26 To improve nonlinear registration, we performed enantiomorphic normalization of the stroke lesion, by filling the stroke lesion with a copy of intact cerebral tissue from the opposite cerebral hemisphere.27,28 WMH masks were incorporated as a cost-function mask, down-weighting their influence on nonlinear registration.28 Stroke lesion masks were transformed to atlas space and overlaid onto CST derived from the JHU white matter atlas. Weighted CST-LL was calculated as a sum of the cross-sectional area of overlap between the stroke lesion and the CST, weighted by the maximum cross-sectional area of the CST.3 This metric quantifies the degree of injury to the CST and accounts for the narrowing of the CST at the internal capsule, with higher CST-LL indicating more extensive overlap of the stroke lesion with the CST.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in R (v.4.3.1). For our primary analysis, we tested the effects of WMH volume, CST-LL, and their interaction on motor impairment with a beta regression model. Beta regression was well suited to our data because motor impairment scores were heavily right skewed and are a bounded proportion (from [0, 1]).29,30 Beta regression is designed to handle data that follows a beta distribution (heavily right-skewed),29,30 and therefore, we did not need to transform our data to fit a normal distribution as with traditional linear regression. We tested assumptions of beta distribution fit with the “fitdistrplus” package. We fit mixed-effects beta regression models with the “glmmTMB” package.31 We tested the effects of WMH volume, CST-LL, and their interaction on motor impairment, with age, days after stroke, and whole-brain stroke lesion volume as covariates and random slopes to control for study site. In line with recommendations from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Sex and Gender-based Analysis policy,32 we conducted a supplementary analysis to explore whether relationships with motor impairment varied by sex. In this supplementary analysis, we included sex as an interaction term with CST-LL and WMH volume.

For our secondary analysis, we tested whether WMH severity modifies relationships between motor impairment, CST-LL, and WMH volume. We stratified the sample into “mild” and “moderate-severe” WMH subgroups with a cutoff for moderate-severe of ≥10 mL WMH volume. This cutoff corresponds to a moderate Fazekas severity rating (periventricular or deep WMH Fazekas score of 2)33 and is a posited threshold for WMH-related neurologic changes.34 We ran beta regression models within each subgroup. The subgroups were underpowered to fit random effects by site; therefore, these beta regression models were fit without random effects.

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Data from 223 individuals with stroke (82 female and 141 male patients) from 7 contributing research sites across 4 countries met our study inclusion criteria (median [interquartile range] age: 67 [58–75]; days post-stroke: 147 [92–1,300]; motor impairment: 5% [0%–27%]; stroke volume [in milliliters]: 2.2 [0.6–16.5]; WMH volume [in milliliters]: 5.3 [1.8–11.7]). In terms of chronicity, 24% of the sample (n = 54) were in the early subacute phase of recovery (>7 and ≤90 days after stroke), 27% (n = 60) in the late subacute phase (>90 and ≤180 days after stroke), and 49% (n = 109) in the chronic phase of recovery (>180 days after stroke).20 The primary sensorimotor assessment used by each study site is included in eTable 1, along with a summary of participant characteristics by site.

WMH volumes were significantly related to Fazekas scores (β = 0.106, p < 0.001; eFigure 1), indicating that SAMSEG accurately estimated WMH volumes.

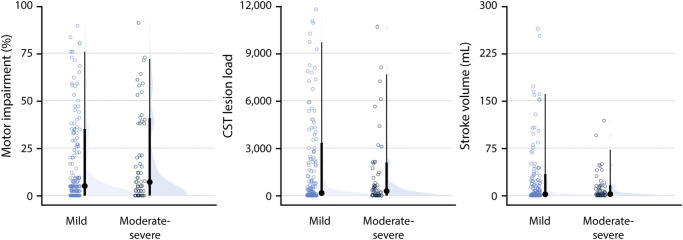

Higher CST-LL and WMH Volume Relate to Worse Motor Impairment After Stroke

We tested our hypothesis that CST-LL, WMH volume, and their interaction relate to motor impairment with mixed-effects beta regression, controlling for age, days after stroke, stroke lesion volume, and research site (as a random effect). Greater CST-LL and larger WMH volumes were related to more severe motor impairment, holding all other factors constant (CST-LL: β = 0.812, p < 0.001; WMH volume: β = 0.178, p = 0.022; Table 1, Figure 1). Age, days after stroke, and stroke volume also significantly related to motor impairment (Table 1). The interaction term between CST-LL and WMH volume was not significant (β = −0.115, p = 0.265). Variance inflation factors (VIFs) in our model were all <1.5, indicating no evidence of significant predictor collinearity. There was no significant interaction effects with sex, indicating that relationships between motor impairment and CST-LL or WMH volume did not vary by sex (eTable 2).

Table 1.

Relationships Between Motor Impairment and Stroke/WMHs

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | p Value |

| Fixed | |||

| Age | −0.332 | 0.076 | <0.001 |

| Days after stroke | 0.335 | 0.084 | <0.001 |

| Stroke volume | −0.228 | 0.103 | 0.027 |

| CST lesion load | 0.812 | 0.241 | 0.001 |

| WMH volume | 0.178 | 0.078 | 0.022 |

| CST lesion load:WMH volume | −0.115 | 0.103 | 0.265 |

| Random | |||

| σ2 | 0.469 | ||

| Nsite | 7 |

Abbreviations: CST = corticospinal tract; WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

Summary statistics and standardized parameter estimates from mixed-effects beta regression models, with harmonized motor impairment score as the outcome measure.

Figure 1. Relationships Between Motor Impairment and Stroke/WMHs.

Motor impairment by CST lesion load (A) or WMH volumes (in milliliters; B). Plots present beta regression line (solid), SE (shaded), and parameter estimates (text). CST = corticospinal tract; WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

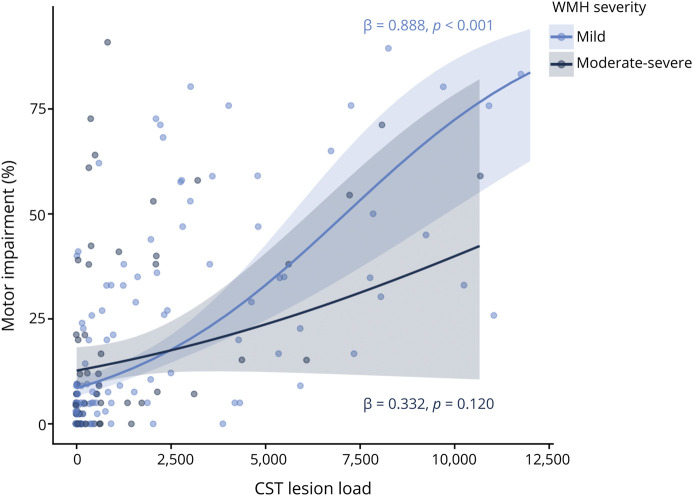

WMH Severity Modifies Relationships Between Motor Impairment and CST-LL/WMHs

There were 162 individuals with mild WMHs and 61 individuals with moderate-severe WMHs in our sample. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests revealed that individuals with mild WMHs were younger than individuals with moderate-severe WMHs (W = 2,824, p < 0.001), but there were no differences between groups in CST-LL (W = 4,805, p = 0.748), stroke lesion volume (W = 5,097, p = 0.717), or severity of motor impairment (W = 4,729, p = 0.618) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Differences in Stroke Characteristics Between Mild and Moderate-Severe WMH Subgroups.

Group differences in WMH subgroup stroke characteristics (light blue = mild WMHs, dark blue = moderate-severe WMHs). Individual data points are plotted against the median and IQR of the data range (solid circles and line) and the density of the data distribution (half-violin plot). CST = corticospinal tract; IQR = interquartile range; WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

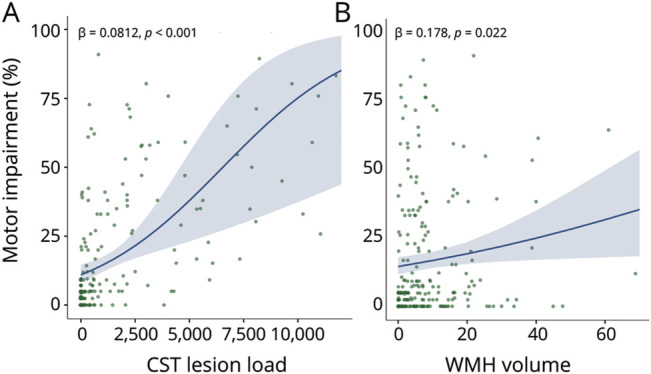

In individuals with mild WMHs, motor impairment was significantly related to CST-LL (β = 0.888, p < 0.001), with a significant CST-LL × WMH volume interaction (β = −0.211, 0.026) indicating individuals with smaller WMH volumes had a stronger relationship between CST-LL and motor impairment (Table 2 and eFigures 2 and 3). In individuals with moderate-severe WMHs, motor impairment related to WMH volume (β = 0.299, p = 0.044), but not CST-LL (β = 0.332, p = 0.120), with no significant CST-LL × WMH volume interaction (Table 2). VIFs were all <1.8 across both WMH severity models, indicating no evidence of significant predictor collinearity. Figure 3 plots relationships between motor impairment and CST-LL for each WMH severity subgroup.

Table 2.

Relationships Between Motor Impairment and Stroke/WMHs, Stratified by WMH Severity

| Predictor | Mild WMHs | Moderate-severe WMHs | ||||

| Estimate | SE | p Value | Estimate | SE | p Value | |

| Age | −0.296 | 0.084 | <0.001 | −0.278 | 0.153 | 0.070 |

| Days after stroke | 0.405 | 0.090 | <0.001 | 0.567 | 0.165 | 0.001 |

| Stroke volume | −0.194 | 0.111 | 0.081 | −0.088 | 0.184 | 0.633 |

| CST lesion load | 0.888 | 0.145 | <0.001 | 0.332 | 0.213 | 0.120 |

| WMH volume | 0.057 | 0.086 | 0.503 | 0.299 | 0.149 | 0.044 |

| CST lesion load:WMH volume | −0.211 | 0.095 | 0.026 | 0.079 | 0.200 | 0.692 |

Abbreviations: CST = corticospinal tract; WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

Summary statistics and standardized parameter estimates from beta regression models, with harmonized motor impairment score as the outcome measure.

Figure 3. Relationships Between Motor Impairment and CST Lesion Load Stratified by WMH Severity.

Motor impairment by CST lesion load, stratified by WMH severity (light blue = mild WMHs, dark blue = moderate-severe WMHs). Plots present beta regression line (solid), SE (shaded), and parameter estimates (text) for stratified models. CST = corticospinal tract; WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

Discussion

In this study, WMH volume related to post-stroke motor impairment over and above CST-LL and stroke volume. WMH severity was an effect modifier35 of CST-LL and motor impairment relationships, meaning the relationship between motor impairment and CST-LL varies in subgroups stratified by WMH severity. In individuals with mild WMHs, there was a significant interaction between CST-LL and WMH volume, such that the relationship between motor impairment and CST-LL was attenuated with larger WMH volumes. In individuals with moderate-severe WMHs, motor impairment related to WMH volume and did not significantly relate to CST-LL. Our findings provide preliminary cross-sectional evidence that WMHs may be an important consideration in building prognostic neurologic models of stroke recovery, especially for individuals with existing moderate-to-severe WMHs.

It is important to contextualize our findings with the existing literature on the CST damage and post-stroke motor outcomes. First, regardless of statistical significance, the effect sizes of CST-LL parameter estimates were greater than those for WMH volume across all tested models. This underscores the importance of stroke-related CST damage as a principle explanatory variable of motor impairment after stroke (see consensus statement from Boyd et al., 20174). Second, our mild and moderate-severe WMH groups did not vary in severity of motor impairment. Therefore, it was not the case that individuals with moderate-severe WMHs (exceeding 10 mL) had worse motor outcomes than individuals with mild WMHs. Rather, we saw that with increased WMH severity, WMH explained greater variability in motor impairment and CST-LL explained less variability in motor impairment. This suggests that WMH severity is an effect modifier of lesion-behavior relationships, not an interactive factor.35 In other words, while WMH volume related to motor impairment across the whole sample, CST-LL and WMH did not have joint synergistic effects on motor impairment. Instead, individuals with moderate-severe WMHs may represent a neurologic subgroup where concurrent age-related cerebrovascular damage has greater explanatory power in post-stroke motor outcomes.

Very few studies to date have examined the impact of WMHs on motor systems, despite the well-known impact of WMHs on widespread white matter networks and connected cortical regions (for review, see Ter Telgte et al., 201836). Research on the impact of WMHs on post-stroke motor outcomes has been equivocal. WMH volume in chronic stroke related to Wolf Motor Function Score in 2 previous reports.37,38 WMH severity in acute stroke consistently relates to total Functional Independence Measure (FIM) score, but the motor subscale of FIM related to WMH severity in some reports,39 but not in others.40,41 Our study considers the combined effects of WMHs and CST damage on post-stroke motor outcome. Our results align with a previous report that individuals with moderate-severe WMHs had an attenuated relationship between stroke lesion volume and overall stroke severity as measured by the NIH Stroke Scale.15

This study contributes important cross-sectional evidence for the impact of WMHs on motor outcomes after stroke. Future research should extend upon these findings using longitudinal designs to test the effects of concurrent WMHs on trajectories of motor recovery. The interaction between WMHs and stroke lesion location could also be evaluated in relationship to somatosensory deficits after stroke as stroke lesion location also relates to proprioceptive outcomes.42 The strengths of our study are the large heterogeneous sample of individuals with stroke and the use of robust methodologies to extract candidate neuroimaging predictors. Although data for this study came from different sites, manual stroke lesion drawings were performed at a single center with standardized protocols.23 Moreover, we have previously demonstrated that our automated WMH segmentation protocol is robust across multiple sites in individuals with stroke.24 Future work could make use of advanced imaging metrics such as diffusion tensor imaging to capture more sensitive quantitative information about the white matter structure in cerebrovascular disease43 and provide further insight into specific damage in patients with poor recovery.8 A limitation of the multisite and secondary nature of our study sample is that we had limited availability of additional covariates that may influence WMH severity and stroke outcomes, including cardiometabolic risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension13 and demographic characteristics such as socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity. Another limitation is that our sample had mild motor impairment overall (median impairment of 5%), which is typical of neuroimaging samples of motor impairment after stroke. However, this limited our ability to test for specific imaging markers of severe upper extremity impairment,44 a patient subgroup where neuroimaging biomarkers may have the greatest benefit for prognostication of recovery.8

In conclusion, our results suggest that WMHs are an under-recognized factor in stroke motor recovery research. WMHs explained variability in motor impairment over and above stroke lesion volume and CST damage. Furthermore, WMH severity might define neurologic subtypes, wherein structural brain reserve has more explanatory power and CST damage has less explanatory power for individuals with extensive preexisting damage to cerebral white matter. Our results will need to be replicated in longitudinal studies to assess the impact and causality of WMHs and CST damage on motor recovery after stroke. The structural reserve of the brain before a stroke injury is increasingly recognized as an important element predicting capacity for motor recovery.9 Including WMHs in motor recovery research could advance models of neurologic recovery by accounting for the full spectrum of cerebrovascular damage in the brain.

Glossary

- CST

corticospinal tract

- CST-LL

CST lesion load

- FIM

functional independence measure

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- VIF

variance inflation factor

- WMH

white matter hyperintensity

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Jennifer K. Ferris, MSc, PhD | Gerontology Research Centre, Simon Fraser University; Department of Physical Therapy and Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Bethany P. Lo, BSc | Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Giuseppe Barisano, MD, PhD | Department of Neurosurgery, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford University, CA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Amy Brodtmann, MBBS, PhD, FRACP | Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne; Department of Medicine, Royal Melbourne Hospital, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Cathrin M. Buetefisch, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, and Department of Radiology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Adriana B. Conforto | Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo; Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Miranda R. Donnelly, MS | Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Natalia Egorova-Brumley, PhD | Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Kathryn S. Hayward | Departments of Physiotherapy, Medicine (RMH) & The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Mohamed Salah Khlif, PhD | Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Kate P. Revill, PhD | Facility for Education and Research in Neuroscience, Emory University, Atlanta, GA | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Artemis Zavaliangos-Petropulu, PhD | Brain Mapping Center, Department of Neurology, Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Lara Boyd, PT, PhD | Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute and Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Sook-Lei Liew, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA | Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, and Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute and Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

J.K. Ferris receives salary support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and Michael Smith Health Research BC (HSIF-2022-2990). This research was funded by the following granting agencies: Australian Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowships (PI Brodtmann: 104748 and 100784; PI Hayward: 106607), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PI Boyd: PTJ-148535, MOP-130269, MOP-106651), Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein (PI Conforto: 2250-14), National Health and Medical Research Council (PI Brodtmann: GNT1020526 GNT1094974 GNT1045617; PI Hayward: 2016420), and NIH (PI Butefisch: R21HD067906; R01NS090677; PI Conforto: R01NS076348-01; PI Liew: R01NS115845; PI Revill: R01NS090677).

Disclosure

A. Conforto was a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim in 2021. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Lawrence ES, Coshall C, Dundas R, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of acute stroke impairments and disability in a multiethnic population. Stroke. 2001;32(6):1279-1284. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.6.1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer S, Verheyden G, Brinkmann N, et al. Functional and motor outcome 5 years after stroke is equivalent to outcome at 2 Months: follow-up of the collaborative evaluation of rehabilitation in stroke across Europe. Stroke. 2015;46(6):1613-1619. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng W, Wang J, Chhatbar PY, et al. Corticospinal tract lesion load: an imaging biomarker for stroke motor outcomes. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(6):860-870. doi: 10.1002/ana.24510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd LA, Hayward KS, Ward NS, et al. Biomarkers of stroke recovery: consensus-based core recommendations from the stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(5):480-493. doi: 10.1177/1545968317732680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayward KS, Schmidt J, Lohse KR, et al. Are we armed with the right data? Pooled individual data review of biomarkers in people with severe upper limb impairment after stroke. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;13:310-319. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy TH, Corbett D. Plasticity during stroke recovery: from synapse to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(12):861-872. doi: 10.1038/nrn2735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plow EB, Cunningham DA, Varnerin N, Machado A. Rethinking stimulation of the brain in stroke rehabilitation: why higher motor areas might Be better alternatives for patients with greater impairments. Neurosci. 2015;21(3):225-240. doi: 10.1177/1073858414537381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayward KS, Ferris JK, Lohse KR, et al. Observational study of neuroimaging biomarkers of severe upper limb impairment after stroke. Neurology. 2022;99(4):E402-E413. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liew SL, Schweighofer N, Cole JH, et al. Association of brain age, lesion volume, and functional outcome in patients with stroke. Neurology. 2023;100(20):E2103-E2113. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duering M, Biessels GJ, Brodtmann A, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease—advances since 2013. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(7):602-618. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00131-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Achten E, et al. Prevalence of cerebral white matter lesions in elderly people: a population based magnetic resonance imaging study. The Rotterdam Scan Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70(1):9-14. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341(7767):c3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeerakathil T, Wolf PA, Beiser A, et al. Stroke risk profile predicts white matter hyperintensity volume: the Framingham study. Stroke. 2004;35(8):1857-1861. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000135226.53499.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georgakis MK, Duering M, Wardlaw JM, Dichgans M. WMH and long-term outcomes in ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2019;92(12):E1298-E1308. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helenius J, Henninger N. Leukoaraiosis burden significantly modulates the association between infarct volume and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(7):1857-1863. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patti J, Helenius J, Puri AS, Henninger N. White matter hyperintensity-adjusted critical infarct thresholds to predict a favorable 90-day outcome. Stroke. 2016;47(10):2526-2533. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuladhar AM, Tay J, Van Leijsen E, et al. Structural network changes in cerebral small vessel disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(2):196-203. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2019-321767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HJ, Im K, Kwon H, et al. Clinical effect of white matter network disruption related to amyloid and small vessel disease. Neurology. 2015;85(1):63-70. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liew SL, Zavaliangos-Petropulu A, Jahanshad N, et al. The ENIGMA Stroke Recovery Working Group: big data neuroimaging to study brain–behavior relationships after stroke. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022;43(1):129-148. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernhardt J, Hayward KS, Kwakkel G, et al. Agreed definitions and a shared vision for new standards in stroke recovery research: the Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable taskforce. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(5):444-450. doi: 10.1177/1747493017711816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liew SL, Zavaliangos-Petropulu A, Schweighofer N, et al. Smaller spared subcortical nuclei are associated with worse post-stroke sensorimotor outcomes in 28 cohorts worldwide. Brain Commun. 2021;3(4):fcab254. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcab254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liew SL, Anglin JM, Banks NW, et al. A large, open source dataset of stroke anatomical brain images and manual lesion segmentations. Sci Data. 2018;5:180011. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo BP, Donnelly MR, Barisano G, Liew SL. A standardized protocol for manually segmenting stroke lesions on high-resolution T1-weighted MR images. Front Neuroimaging. 2022;1:1098604. doi: 10.3389/fnimg.2022.1098604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferris JK, Lo BP, Khlif MS, Brodtmann A, Boyd LA, Liew SL. Optimizing automated white matter hyperintensity segmentation in individuals with stroke. Front Neuroimaging. 2023;2:1099301. doi: 10.3389/fnimg.2023.1099301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. Am J Neuroradiol. 1987;8(3):421-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, Smith S. Non-Linear Registration Aka Spatial Normalisation. FMRIB Technical Report TR07JA2. 2007. Accessed October 25, 2016. fmrib.medsci.ox.ac.uk/analysis/techrep/tr07ja2/tr07ja2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nachev P, Coulthard E, Jäger HR, Kennard C, Husain M. Enantiomorphic normalization of focally lesioned brains. Neuroimage. 2008;39(3):1215-1226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferris J, Greeley B, Yeganeh NM, et al. Exploring biomarkers of processing speed and executive function: the role of the anterior thalamic radiations. NeuroImage Clin. 2022;36:103174. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2022.103174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrari SLP, Cribari-Neto F. Beta regression for modelling rates and proportions. J Appl Stat. 2004;31(7):799-815. doi: 10.1080/0266476042000214501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swearingen CJ, Tilley BC, Adams RJ, et al. Application of beta regression to analyze ischemic stroke volume in NINDS rt-PA clinical trials. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;37(2):73-82. doi: 10.1159/000330375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks ME, Kristensen K, van Benthem KJ, et al. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 2017;9(2):378-400. doi: 10.32614/rj-2017-066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Sex and Gender in Health Research. 2021. Accessed October 29, 2023. cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50833.html. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joo L, Shim WH, Suh CH, et al. Diagnostic performance of deep learning-based automatic white matter hyperintensity segmentation for classification of the Fazekas scale and differentiation of subcortical vascular dementia. PLoS One. 2022;17(9):e0274562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeCarli C, Murphy DGM, Tranh M, et al. The effect of white matter hyperintensity volume on brain structure, cognitive performance, and cerebral metabolism of glucose in 51 healthy adults. Neurology. 1995;45(11):2077-2084. doi: 10.1212/WNL.45.11.2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corraini P, Olsen M, Pedersen L, Dekkers OM, Vandenbroucke JP. Corrigendum: effect modification, interaction and mediation: an overview of theoretical insights for clinical investigators (Clin Epidemiol 2017;9:331-338). Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:245. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S198519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ter Telgte A, Van Leijsen EMC, Wiegertjes K, Klijn CJM, Tuladhar AM, De Leeuw FE. Cerebral small vessel disease: from a focal to a global perspective. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(7):387-398. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0014-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auriat AM, Ferris JK, Peters S, et al. The impact of covert lacunar infarcts and white matter hyperintensities on cognitive and motor outcomes after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(2):381-388. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hicks JM, Taub E, Womble B, et al. Relation of white matter hyperintensities and motor deficits in chronic stroke. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2018;36(3):349-357. doi: 10.3233/RNN-170746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Senda J, Ito K, Kotake T, et al. Association of leukoaraiosis with convalescent rehabilitation outcome in patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2016;47(1):160-166. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan M, Heiser H, Bernicchi N, et al. Leukoaraiosis predicts short-term cognitive but not motor recovery in ischemic stroke patients during rehabilitation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(6):1597-1603. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.02.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawe RL, Findlater SE, Kenzie JM, Hill MD, Scott SH, Dukelow SP. Differential impact of acute lesions versus white matter hyperintensities on stroke recovery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(18):e009360. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hassa T, Zbytniewska-Mégret M, Salzmann C, et al. The locations of stroke lesions next to the posterior internal capsule may predict the recovery of the related proprioceptive deficits. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1248975. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1248975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pasi M, Van Uden IWM, Tuladhar AM, De Leeuw FE, Pantoni L. White matter microstructural damage on diffusion tensor imaging in cerebral small vessel disease: clinical consequences. Stroke. 2016;47(6):1679-1684. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodics T, Cohen LG, Cramer SC. Functional imaging of intervention effects in stroke motor rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(12 suppl 2):36-42. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.