Abstract

Some vestibular schwannoma (VS) show cystic morphology. It is known that these cystic VS bear different risk profiles compared to solid VS in surgical treatment. Still, there has not been a direct comparative study comparing both SRS and SURGERY effectiveness in cystic VS. This retrospective bi-center cohort study aims to analyze the management of cystic VS compared to solid VS in a dual center study with both microsurgery (SURGERY) and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS). Cystic morphology was defined as presence of any T2-hyperintense and Gadolinium-contrast-negative cyst of any size in the pre-interventional MRI. A matched subgroup analysis was carried out by determining a subgroup of matched SURGERY-treated solid VS and SRS-treated solid VS. Functional status, and post-interventional tumor volume size was then compared. From 2005 to 2011, N = 901 patients with primary and solitary VS were treated in both study sites. Of these, 6% showed cystic morphology. The incidence of cystic VS increased with tumor size: 1.75% in Koos I, 4.07% in Koos II, 4.84% in Koos III, and the highest incidence with 15.43% in Koos IV. Shunt-Dependency was significantly more often in cystic VS compared to solid VS (p = 0.024) and patients with cystic VS presented with significantly worse Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) compared to solid VS (p < 0.001). The rate of GTR was 87% in cystic VS and therefore significantly lower, compared to 96% in solid VS (p = 0.037). The incidence of dynamic volume change (decrease and increase) after SRS was significantly more common in cystic VS compared to the matched solid VS (p = 0.042). The incidence of tumor progression with SRS in cystic VS was 25%. When comparing EOR in the SURGERY-treated cystic to solid VS, the rate for tumor recurrence was significantly lower in GTR with 4% compared to STR with 50% (p = 0.042). Tumor control in cystic VS is superior in SURGERY, when treated with a high extent of resection grade, compared to SRS. Therapeutic response of SRS was worse in cystic compared to solid VS. However, when cystic VS was treated surgically, the rate of GTR is lower compared to the overall, and solid VS cohort. The significantly higher number of patients with relevant post-operative facial palsy in cystic VS is accredited to the increased tumor size not its sole cystic morphology. Cystic VS should be surgically treated in specialized centers.

Keywords: Vestibular schwannoma, Acoustic neuroma, Outcome, Tumor recurrence, Stereotactic radiosurgery, Microsurgery

Introduction

Vestibular schwannoma (VS) are benign tumors that arise from the vestibulocochlear nerve complex and represent ca. 90% of all neoplasms occupying the cerebellopontine angle (CPA) [1, 2]. VS can show different morphological characteristics (e.g. size, CPA extension, intracanalicular extension, flow-voight, etc.), but the best known magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) feature in VS are the development of cysts, which are visible in T2-weighted MRI. Cystic VS are associated with either intra- or extratumoral cysts that develop in the loosely organized Antoni B tissues [3]. VS cysts are thought to arise from recurrent microbleeding or osmosis-induced expansion of cerebrospinal fluid trapped in arachnoid tissue, leading to T2 hyperintense signal and variable T1 signal [4–6].

Even though the exact pathophysiology of these evolved cysts are not definitely known, its direct consequence into patient management has already been described and discussed in the past: Cystic VS can demonstrate a more rapid growth and expansion [7], enhanced peritumoral adhesion [8–10], worse post-operative facial nerve outcome [11]. Concordant to solid VS, both radiosurgery (SRS) and microsurgical resection (SURGERY) are possible treatment modalities.

Several studies have shown safety and effectiveness of SRS in cystic VS, one even going so far to state that cystic VS respond better to SRS due to the more pronounced volume reduction VS compared to solid VS [4, 12, 13]. Still, there has not been a direct comparative study comparing both SRS and SURGERY effectiveness in cystic VS. This study aims to analyze the management of cystic VS compared to solid VS in a dual center study of SURGERY and SRS treated VS patients.

Methods

Study design & patient cohort

This is a retrospective dual-center cohort study. Patients were identified by a prospectively kept registry by both senior authors (G. H. and M. T.). Data was then retrospectively collected from both tertiary and specialized centers involved in the treatment of VS between 2005 und 2011 to enable follow-up (FU) of up to 10 years. Part of this data has been published before as this is a subgroup analysis [14].

Treatment modalities

Patients treated by SURGERY were all operated by retrosigmoid approach using intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring. Patients were either operated in semi-sitting or supine position [15]. All VS patients in the SRS cohort received Gamma-Knife-Radiosurgery (GKR - Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden) with a prescription dose of 13 Gy to the 65% isodose line as a standard dose and a mean Paddick Conformity Index of 0.81 (± SD0.11) in the whole cohort. The treatment plan spared the cochlea in order to enable a higher chance on hearing preservation.

Data collection

Cystic morphology was defined as presence of T2-hyperintense and Gadolinium-contrast-negative cyst of any size in the pre-interventional MRI. Tumor size was classified by Koos Classification [16]. Previously treated VS and VS associated with Neurofibromatosis were systematically excluded. Clinical state was reported by House and Brackmann (H&B) and Gardner-Robertson (G&R) scale (with H&B and G&R 1–2 considered as good functional outcome), and Recurrence-free-survival (RFS) was assessed radiographically by contrast-enhanced MR imaging [17, 18]. The criteria for tumor recurrence/progression was defined as a progredient growth in Gadolinium contrast-enhanced MRI (radiographic tumor control = RTC). To exclude the previously described phenomenon of pseudoprogression after SRS of VS, patients with tumor volume (TV) increase 6 months after SRS with stable TV afterwards or TV decrease were not graded as VS recurrence/progression [19]. The TV was measured using slice-by-slice manual contouring. In SRS, pseudoprogression was defined as transient tumor volume increase > 30% within the first two years after SRS-treatment. Early recurrence was defined as tumor volume increase > 30% persisting over 2 years after treatment.

In case of SURGERY, extent of resection (EOR) was classified by first post-operative Gadolinium-enhanced MRI 3 months post-operatively in the following manner: residual contrast-enhancing tumor was defined as subtotal resection (STR), whereas gross total resection (GTR) was defined as lack of contrast-enhancement in the MRI. Secondary VS symptoms like trigeminal affection, tinnitus and vertigo were also collected retrospectively.

Statistical analysis

A matched subgroup analysis (1:1) was carried out by determining a subgroup of SURGERY-treated solid VS (closest match for tumor size, age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [20] and EOR) and SRS-treated solid VS (closest match for tumor size, age, sex, and CCI). Functional status, and post-interventional tumor volume size was then compared.

Statistical analysis was performed in R Studio (Version 1.2) using descriptive statistics. To compare non-numeric parameters of both groups, the chi-square test, and Fisher-T-test (for small sample size) was applied. For numeric parameters, Welch’s two sample t-test was used. Recurrence/Progression-free survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between cases and controls using a log-rank test. The length of FU for recurrence/progression-free survival was calculated from the date of surgical intervention to the date of either recurrence/progression or the last clinical visit. Significance was defined as the probability of a two-sided type 1 error being < 5% (p < 0.05). Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) if not indicated otherwise.

Results

Study cohort

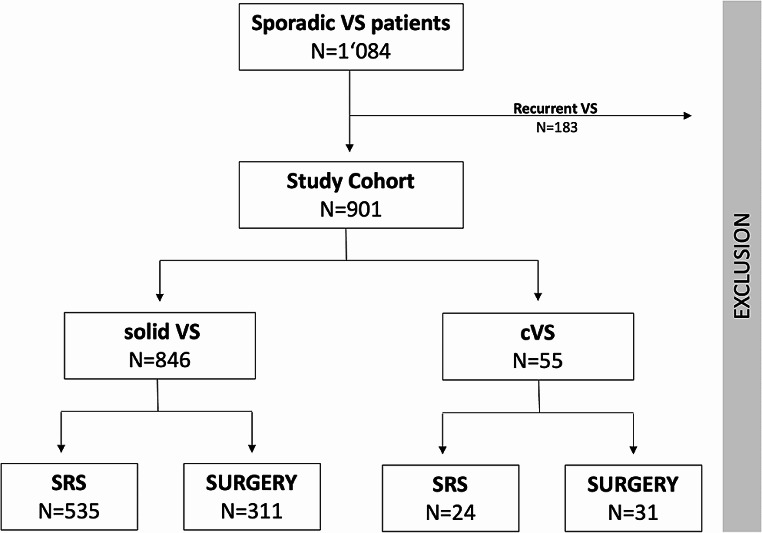

From 2005 to 2011, N = 901 patients with primary and solitary VS were treated in both centers. 6% showed cystic morphology at the pre-interventional MRI, while 94% VS were classified as solid VS (Fig. 1). The rate of SURGERY was significantly higher in cystic VS with a rate of 56%, compared to 37% in solid VS (p = 0.006).

Fig. 1.

Patient cohort flowchart

Mean age of patients with solid VS was 54.54 (± 13.52) years and for cystic VS 54.93 (± 16.42) years. There was no significant difference in age, when comparing the cohort of cystic with solid VS (p = 0.838). Cystic VS significantly more frequently reached size Koos IV (Table 1). Therefore, the incidence of cystic VS increased with tumor size: 1.75% in Koos I, 4.07% in Koos II, 4.84% in Koos III, and the highest incidence with 15.43% in Koos IV. Shunt-Dependency was significantly more prevalent in cystic compared to solid VS (p = 0.024) and patients with cystic VS presented with significantly worse CCI compared to solid VS (p < 0.001). The incidence of recurrence/progression was higher in cystic VS (16%) compared to solid VS (9%), but this did not reach statistical significance. The incidence of pre-operative trigeminal neuralgia and vertigo as secondary VS-related symptoms were significantly higher in cystic VS compared to solid VS.

Table 1.

Tumor and patient demographics solid VS vs. cVS

| All (N = 901) |

solid VS (N = 846) |

cVS (N = 55) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.47(± 13.70) | 54.54(± 13.52) | 54.93(± 16.42) | 0.838 |

| Female | 502 (56) | 467 (55) | 35 (64) | 0.262 |

| Koos Classification | ||||

| Koos I | 114 (12) | 112 (13) | 2 (4) | 0.035 |

| Koos II | 295 (33) | 283 (34) | 12 (22) | 0.077 |

| Koos III | 330 (37) | 314 (37) | 16 (29) | 0.251 |

| Koos IV | 162 (18) | 137 (16) | 25 (45) | < 0.001 |

| Shunt-Dependency | 19 (2) | 15 (2) | 4 (7) | 0.024 |

| Recurrence / Progression | 84 (9) | 75 (9) | 9 (16) | 0.088 |

| Comodbidities | ||||

| Charlson Index | 0.22(± 0.73) | 0.20(± 0.68) | 0.55(± 1.20) | < 0.001 |

| 0 | 807 (90) | 764 (90) | 43 (79) | 0.009 |

| 1 | 33 (4) | 30 (4) | 3 (5) | 0.447 |

| 2 | 35 (4) | 31 (4) | 4 (7) | 0.159 |

| 3 | 11 (1) | 9 (1) | 2 (4) | 0.141 |

| > 3 | 15 (2) | 12 (1) | 3 (5) | < 0.001 |

Values are presented as the number of patients (%) unless indicated otherwise. Significant p-values (< 0.05) are highlighted in bold

Surgical and radiosurgical management

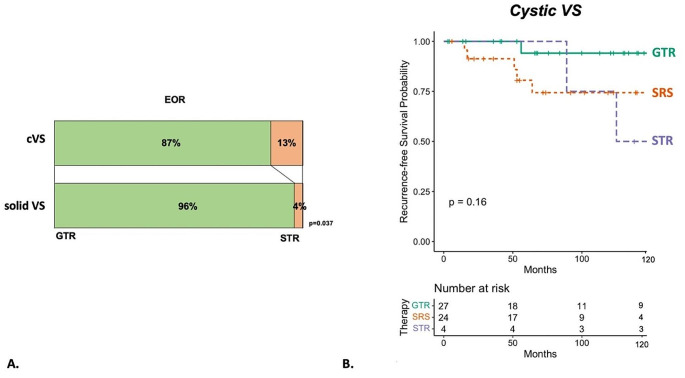

The rate of GTR was 87% in cystic VS and therefore significantly lower, compared to 96% in solid VS (p = 0.037) (Fig. 2). Cystic VS treated with SURGERY were significantly younger compared to cystic VS treated with SRS (p < 0.001). Moreover, the SURGERY group of cystic VS consisted of significantly larger tumor size (in Koos Classification) (Table 2). Shunt-Dependency and incidence of recurrence/progression was higher in SRS-treated cystic VS, but this did not reach statistical significance in this study cohort (p = 0.307 and p = 0.157 respectively). Premorbid status was statistically insignificant in cystic VS, when comparing either therapy. Mean treated tumor volume was 4.95 (± 3.28) cm3 with a tumor isodose volume of 4.89 (± 3.19) cm3.

Fig. 2.

(A) shows the distribution in EOR in cystic VS (cVS) compared to solid VS. (B) shows a Kaplan-Meier-Analysis comparing time to recurrence/progression in cVS treated with GTR, STR and SRS with GTR ensuring the highest rate of tumor control

Table 2.

Tumor and Patient Demographics of cVS treated with SRS and SURGERY

|

SRS

(N = 24) |

SURGERY

(N = 31) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.33(± 14.21) | 47.65(± 14.32) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 19 (79) | 16 (52) | 0.049 |

| Koos Klassification | |||

| Koos I | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0.185 |

| Koos II | 11 (46) | 1 (3) | < 0.001 |

| Koos III | 9 (38) | 7 (23) | 0.248 |

| Koos IV | 2 (8) | 23 (74) | < 0.001 |

| Shunt-Dependency | 3 (13) | 1 (3) | 0.307 |

| Recurrence / Progression | 6 (25) | 3 (10) | 0.157 |

| Charlson Comorbidities Index (CCI) | 0.75(± 1.22) | 0.39(± 1.17) | 0.271 |

Values are presented as the number of patients (%) unless indicated otherwise. Significant p-values (< 0.05) are highlighted in bold

Functional outcome

The overall incidence for treatment-related side-effects was 7%, with no significant difference depending on cystic morphology (p = 0.48). The complication rate in cystic VS treated with SURGERY was 6%, and 15% in solid VS (SURGERY) with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.296). The incidence of treatment-related side-effects was 0% in cystic VS treated with SRS and 2% in solid VS (SRS) (p = 1). The most common SRS-related side effects were symptomatic brain edema or hydrocephalus, while SURGERY-related complications were CSF fistula, hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, sinus thrombosis, symptomatic pneumocephalus, hygroma, and infection (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Pre- and postoperative status in secondary VS-related symptoms: facial spasm, tinnitus, trigeminus, vertigo and incidence of treatment-related side effects classified in Clavin-Dindo-Classification (CDC) [21]

| All (N = 901) |

Solid VS (N = 846) | Cystic VS (N = 55) |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| preoperative clinical status | |||||

| Facial Spasm | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| Tinnitus | 663 (74) | 619 (73) | 44 (80) | 0.343 | |

| Trigeminus | 94 (10) | 82 (10) | 12 (22) | 0.009 | |

| Vertigo | 549 (61) | 504 (60) | 45 (82) | < 0.001 | |

| postoperative clinical status | |||||

| Facial Spasm | 28 (3) | 28 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.407 | |

| Tinnitus | 264 (29) | 247 (29) | 17 (31) | 0.761 | |

| Trigeminus | 54 (6) | 48 (6) | 6 (11) | 0.133 | |

| Vertigo | 359 (40) | 340 (40) | 19 (35) | 0.478 | |

| Treatment Complications / Side Effects | 62 (7) | 60 (7) | 2 (4) | 0.577 | |

| Clavien-Dindo-Classification (CDC) | |||||

| 2 | 21 (2) | 20 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 | |

| 3a | 29 (3) | 28 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 | |

| 3b | 12 (1) | 12 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 | |

| > 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | |

Values are presented as the number of patients (%) unless indicated otherwise. Significant p-values (< 0.05) are highlighted in bold

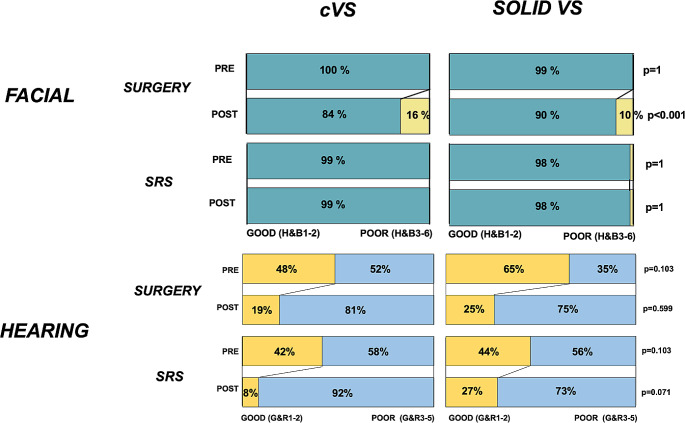

Post-operative facial and hearing function was similar in cystic VS compared to solid VS. Postinterventional facial function was significantly worse in patients treated with SURGERY compared to SRS (Fig. 3). Still, within the SURGERY-treated VS, patients with cystic VS more often presented with relevant post-operative facial function.

Fig. 3.

Rates of functional status in facial and hearing function in cVS (N = 55) and solid VS (N = 849) treated with either SURGERY or SRS. Good facial function was defined as H&B1-2, and poor status as H&B3-6. Good hearing status was defined as G&R1-2, and poor status as G&R3-5. Values are presented as the number of patients (%) unless indicated otherwise. Significant p-values (< 0.05) are highlighted in bold

Matched comparison subgroup analysis

To confirm/deny the hypothesis that cystic fared worse after SURGERY compared to their solid counterparts, we conducted a subgroup-analysis with a matched cohort (1:1) of solid VS (N = 31) with similar tumor characteristics as cVS treated by SURGERY- as the tumor size distribution were statistically different in the cystic and solid tumors. Here, the incidence of relevant, post-operative long-term facial palsy was 23% in a comparative solid VS group (compared to 16% in cVS treated by SURGERY) (p = 0.749). Shunt-Dependency was similar in the matched solid VS groups with 6% compared to 3% cVS (p = 0.350). Same applied to the incidence of pre- and post-operative vertigo and hearing function: Neither was significantly higher in cystic VS compared to solid VS, when the factor of tumor sizing was dissolved (74%; p = 0.780 and 58%; p = 0.611).

A direct matched comparative subgroup analysis was also performed in the SRS-group. The rate of long-term tumor progression was higher in cVS (25%) treated by SRS compared to same-sized sVS (13%), however, it did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.461). The pattern of volume change within the first 2 years after SRS-treatment in this subgroup-analysis is shown in Table 4. The incidence of dynamic volume change (tumor volume decrease, pseudoprogression, or volume increase was significantly more common in cystic VS compared to the matched solid VS (p = 0.042).

Table 4.

Incidence of different patterns of volume change within 2 years after SRS in cystic VS compared to matched solid VS

| Cystic VS (N = 24) | matched solid VS (N = 24) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| same tumor size (± 30%) | 8 (33) | 16 (66) | 0.042* |

| tumor volume decrease (> 30%) | 7 (29) | 3 (13) | 0.286 |

| pseudoprogression | 6 (25) | 1 (4) | 0.097 |

| early tumor progression | 3 (13) | 4 (17) | 1 |

Values are presented as the number of patients (%) unless indicated otherwise. Significant p-values (< 0.05) are highlighted in bold

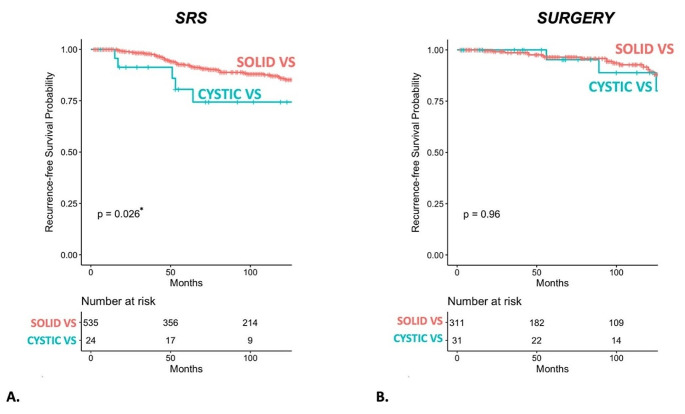

Tumor control

Overall mean time of FU was 6.69 (± 4.44) years in cystic VS and 6.23 (± 4.36) years in the overall study cohort. SURGERY as a monotherapy was able to ensure a comparable tumor control in cystic VS compared to solid VS. However, SRS showed inferior tumor control in cystic VS with 25% treatment failure compared to SRS-treated solid VS with 10% treatment failure (p = 0.014). Incidence rates are shown in Table 5. When comparing EOR in the SURGERY-treated cystic VS, the rate for tumor recurrence/progression was significantly lower in GTR with 4% compared to STR with 50%, and SRS with 25% (p = 0.042; p = 0.037), making GTR the best treatment choice considering tumor control (compared to STR and SRS).

Table 5.

Incidence of recurrence/progression in solid VS and cVS treated with SURGERY or SRS

| Solid VS (N = 846) | Cystic VS (N = 55) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRS |

10% (N = 53/535) |

25% (N = 6/24) |

0.014 |

| SURGERY |

7% (N = 22/311) |

10% (N = 3/31) |

0.484 |

| p-value | 0.170 | 0.157 |

Values are presented as the number of patients (%) unless indicated otherwise. Significant p-values (< 0.05) are highlighted in bold

In GTR-treated cystic VS (N = 1), time to recurrence was 4.67 years. When treated with STR, mean time to recurrence was 8.92 (± 2.12) years. In SRS-treated cystic VS, mean time to recurrence was significantly shorter compared to STR at 5.04 (± 4.51) years (p < 0.001). Mean time to tumor progression of SRS-treated cystic VS was statistically insignificant compared to solid VS treated with SRS 6.37 (± 4.33) years (p = 0.142). Kaplan-Meier-Analysis on SRS and SURGERY in solid versus cystic VS is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

(A) shows a Kaplan-Meier-Analysis comparing progression-free-survival in cVS and solid VS, when treated with SRS. (B) shows recurrence-free-survival in cVS and solid VS when treated with SURGERY.

Discussion

From all treated solitary, primary VS, 6% showed MR-graphic cystic character in this study. The majority of cystic VS was treated with SURGERY. Premorbid status was worse in cystic compared to solid VS. Generally, cystic VS were larger compared to solid VS and more often required hydrocephalus-related treatment (i.e. shunt surgery). The incidence of pre-operative trigeminal and vertigo-related symptoms are significantly more frequent in cystic VS compared to solid tumors – but not higher compared to same-size solid VS. SRS was inferior in tumor control (i.e. RFS) in cystic VS compared to solid VS. The highest rate of tumor control was ensured, when treated with GTR (compared to SRS and STR). The rate of GTR, however, is significantly lower in cystic VS compared to surgically treated solid VS. In the general cohort, poor postoperative facial outcome was significantly more prevalent in cystic VS, but not worse compared to same-size solid VS. Cystic morphology was not associated with a higher rate of therapy-related side-effects.

Patient and tumor characteristics solid vs. cystic VS

The incidence of cystic morphology in the VS is reported with considerable variability: from 11.3 to 48% [9, 22, 23]. This cohort shows an overall incidence of 6% of the treated primary, solitary VS similar to Fundova et al. in 2000, when 773 VS patients were retrospectively reviewed [24]. However, the incidence of cyst formation rises with tumor size with the lowest rate in Koos I at 2% and the highest incidence in Koos IV VS at 15.43%, this distribution could attribute to the reported incidence discrepancies [25].

The CCI was significantly higher in patients with cystic VS compared to solid, suggesting that there was a significantly worse premorbid status in these patients, even though age is indifferent in either group. Even though the exact pathophysiology of cyst formation is not entirely clear, it has been related to micro-hemorrhages and inflammation process and one could imagine, this being a possible effect of the patients’ overall health condition or relevant comorbidities [8, 26].

The incidence of trigeminal symptoms and vertigo was significantly raised in cystic VS compared to solid VS. This has also been shown and discussed by Constanzo et al. in 2019, who showed that patients with cystic VS faired objectively worse in video head impulse testing and therefore was associated with worse vestibular dysfunction [26]. Constanzo et al. attribute this difference to a local inflammatory reaction caused by hemorrhages, which would induce a ‘‘neuritis’’ of the vestibular nerves, therefore altering vestibulo-ocular reflex gain beyond what its expected [26]. However, in our matched subgroup-analysis, where tumor size was taken out of the equation as a potential bias, there was no significant difference in vertigo, trigeminal affection, hearing status and even facial nerve outcome. This suggests that the pronounced clinical features of a cystic VS is most likely caused by the sheer space demanding tumor volume in the CPA. The incidence of Shunt-Dependency was also significantly higher in the cystic VS cohort, which has been described in the past [25, 27].

Radiosurgery vs. microsurgery

Patients treated by SRS were significantly older compared to cystic VS treated with SURGERY, which is a phenomenon often described in the past [14, 28–30]. Interestingly, women more often received SRS than men. However, this study design does not allow any investigation to any sex-related difference in provided VS care. However, differences in provided surgical care have been described in the past – although it remains unclear, whether this phenomenon is a result of medical care provider bias or gender-related decision-making by the patient [31, 32].

It has been repeatedly shown in the past that SRS is safe in cystic VS with a high rate of functional preservation [1, 4, 12, 33]. Within the SRS-group, however, it was not able to ensure the same RFS in cystic VS as in solid VS (75% versus 90%). When treated with SRS, the incidence of post-SRS tumor volume change (increase, decrease or pseudoprogression) was significantly higher in cystic VS in the matched subgroup analysis. This phenomenon has been described by previous studies focusing on SRS in cystic VS, who describe a significant tumor volume decrease in macrocystic compared to solid VS [1, 12, 34, 35].

Bowden et al. observed a very high tumor control rate of > 95% (compared to 75% in this study) with a mean follow-up of 4 years. However, our data shows a mean time to recurrence/progression in the SRS-treated cystic VS at > 5 years. It is possible that past studies have not been able to report the true incidence of recurrence, when cystic was treated with SRS as a monotherapy [4, 12, 13]. In 2016, Frisch et al. reported a tumor control of 80% in cystic VS with a mean follow-up of 5.25 years, which more reflects to the results presented in our study [1]. These differences point out the importance of long-term FU when discussing RFS in a benign tumor, such as VS.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare SRS and SURGERY of cystic VS in one study design. Noticeably, if tumor recurrence/progression appeared, mean time to recurrence/progression after SRS-treatment was significantly shorter compared to STR or GTR – even though pseudoprogression was systematically ruled out in this study. Therefore, the tumor volume increase in cystic VS is most likely due to the fluid uptake in the intratumoral cyst and not due to increase in contrast-enhancing tumor tissue. Concordant, cystic schwannomas are histologically associated with a 36-fold decrease in nuclear proliferation as measured with Ki-67 staining when compared with solid tumors. This suggests that the rapid clinical growth seen in cystic schwannomas is related to the accumulation of fluid during cyst formation and not by an actual increase in the growth rate of tumor cells [3, 36].

The predicament of surgery of cystic VS

The prognosis after SURGERY is reported to be worse than for other solid VS because of the difficulty in preserving the arachnoid plane, the presence of hypervascular solid portions of the tumor, unusual cranial nerve displacement, and a greater tendency for postoperative bleeding [5, 6, 8, 37, 38]. Therefore, cystic VS presents a therapeutic dilemma and should preferably be treated in specialized centers routinely treating solid VS.

Safe maximal resection—if achievable—would to date be the best long-term tumor control in cystic VS according to our results. However, cystic morphology is associated with a lower rate of EOR (GTR 87% vs. 96%), when treated with SURGERY in this study cohort. A comparative study in 2005 achieved a high GTR-rate in cystic tumors of 92% (solid tumors 93%) by retrosigmoid approach, but they also report that 42% of patients with cystic VS showed unfavorable facial nerve function one year post-operatively [9]. Notably, their classification for good facial outcome included HB grade 3, which was classified as poor facial outcome in our study. In 2000, Fundova et al. reported a substantially higher rate of complete facial nerve loss in cystic compared to solid VS (41% versus 27% respectively) with similar GTR rates in both groups (89% and 82%) [24].

The rate of poor facial outcome (HB3-6 after one year) was rather low with 16% in cystic VS and comparable in same sized solid VS in our study compared to the literature. Jian et al. presented a cohort with significantly different achieved EOR with 52% of GTR in cystic and 70% in solid VS, this constellation yielded in insignificantly different facial function outcome in either group [39]. In summary, studies on cystic VS yielded in comparable facial nerve outcome, when the rate of STR was higher compared to solid VS suggesting a direct correlation between EOR and facial nerve outcome [7, 11, 39–41].

A trend towards a more conservative surgical approach, which has also been reported in a longitudinal analysis by Piccirillo et al. in 2009, may conceal the worse facial function resulted by the cystic morphology [42]. Facial function has been shown to be a major predictor of VS patients’ quality of life [28]. Along with the unfavorable prognosis after SRS, it is enticing to conclude that a combination approach, e.g. STR with cyst resection followed by STR in cystic VS might ensure best facial nerve outcome and tumor control [2, 43]. Still, before putting these kinds of recommendations forward, further investigation must be done, on how the solid residual tumor reacts to SRS. It has been described that SRS may cause the micro-hemorrhages and therefore, could promote new cyst formation in tumor tissue already prone to cyst formation [6, 44, 45]. Yang et al. have shown retrospectively that adjuvant SRS after complete cyst removal ensures higher tumor control rates then in solid VS, however, their mean time of follow up was 4.5 years, which for a benign tumor such as VS may be too short of a follow-up [43]. A prospective study on a combination approach in cystic VS has yet to be done. As STR significantly prolongs mean time to recurrence to 8.92 years, STR can be a valid option for Elderly patients with cystic VS.

Limitations of this study

This study is limited by its nature of retrospective design, even though it involves more than one study center. This study involved a large group of patients with cystic tumor characteristics, however, the patient number and its value has to be put into its statistical context. An even larger patient cohort could even allow subgroup analyses within cystic VS (e.g. micro- and macrocystic morphology).

Conclusion

Tumor control in cystic VS is superior with SURGERY, when treated with a high EOR, compared to SRS. However, when cystic VS is treated surgically, the rate of GTR is lower and the number of patients with relevant postoperative facial palsy higher compared to solid VS in general, but not higher compared to same-sized solid VS. Therefore, cystic morphology in VS poses a challenge in the management (both SRS and SURGERY) compared to solid tumors. Treatment decision and patients’ consultation should contemplate and address negative prognostic factor of cystic morphology in VS.

Abbreviations

- ARI

Absolute Risk Reduction

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidities Index

- CDC

Clavien-Dindo-Classification

- CTC

Clinical tumor control

- DS

Decompression surgery

- ENT

Ear, Nose and Throat

- EOR

Extent of resection

- FU

Follow-up

- GKR

Gamma-Knife radiosurgery

- GR

Gardner-Robertson

- GTR

Gross total resection

- H&B

House-Brackman

- KPS

Karnofsky Performance Score

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- N/A

Not applicable

- RTC

Radiographic tumor control

- SRS

Stereotactic radiosurgery

- ST

Salvage therapy

- STR

Sub-total resection

- TV

Tumor volume

- VS

Vestibular schwannoma

Author contributions

Conception and design: MS, SW. Acquisition of data: AR, SW. Analysis and interpretation of data: SW, MT, GH. Statistical analysis: SW. Drafting the article: SW, MT. Critically revising the article: GN, FE, AE, GH. Reviewed submitted version of the manuscript: SW.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding or financial support.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study adheres to the ethical guidelines and has been approved by the local ethics committee (Ethikkommission Tübingen). Owing to the retrospective nature of the study and approval by the ethics committee, patient consent was not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Frisch CD, Jacob JT, Carlson ML et al (2017) Stereotactic radiosurgery for cystic vestibular schwannomas. Neurosurgery 80(1):112–118. 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001376 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Goldbrunner R, Weller M, Regis J et al (2020) EANO guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of vestibular schwannoma. Neuro Oncol 11(1):31–45. 10.1093/neuonc/noz153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neff BA, Welling DB, Akhmametyeva E, Chang LS (2006) The molecular biology of vestibular schwannomas: dissecting the pathogenic process at the molecular level. Otol Neurotol 27(2):197–208. 10.1097/01.mao.0000180484.24242.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim SH, Park CK, Park BJ, Lim YJ (2019) Long-term outcomes of gamma knife radiosurgery for cystic vestibular schwannomas. World Neurosurg 132:e34–e39. 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piccirillo E, Wiet MR, Flanagan S et al (2009) Cystic vestibular schwannoma: classification, management, and facial nerve outcomes. Otol Neurotol 30(6):826–834. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181b04e18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park CK, Kim DC, Park SH et al (2006) Microhemorrhage, a possible mechanism for cyst formation in vestibular schwannomas. J Neurosurg 105(4):576–580. 10.3171/jns.2006.105.4.576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yashar P, Zada G, Harris B, Giannotta SL (2012) Extent of resection and early postoperative outcomes following removal of cystic vestibular schwannomas: surgical experience over a decade and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 33(3):E13. 10.3171/2012.7.FOCUS12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia L, Zhang H, Yu C et al (2014) Fluid-fluid level in cystic vestibular schwannoma: a predictor of peritumoral adhesion. J Neurosurg 120(1):197–206. 10.3171/2013.6.JNS121630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benech F, Perez R, Fontanella MM, Morra B, Albera R, Ducati A (2005) Cystic versus solid vestibular schwannomas: a series of 80 grade III-IV patients. Neurosurg Rev 28(3):209–213. 10.1007/s10143-005-0380-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon KS, Jung S, Seo SK et al (2007) Cystic vestibular schwannomas: a possible role of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in cyst development and unfavorable surgical outcome. J Neurosurg 106(5):866–871. 10.3171/jns.2007.106.5.866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thakur JD, Khan IS, Shorter CD et al (2012) Do cystic vestibular schwannomas have worse surgical outcomes? Systematic analysis of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 33(3):E12. 10.3171/2012.6.FOCUS12200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowden G, Cavaleri J, Monaco E III, Niranjan A, Flickinger J, Lunsford LD (2017) Cystic vestibular schwannomas respond best to radiosurgery. Neurosurg 1(3):490–497. 10.1093/neuros/nyx027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peker S, Samanci Y, Ozdemir IE, Kunst HPM, Eekers DBP, Temel Y (2022) Long-term results of upfront, single-session gamma knife radiosurgery for large cystic vestibular schwannomas. Neurosurg Rev 6(1):2. 10.1007/s10143-022-01911-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tatagiba M, Wang SS, Rizk A et al (2023) A comparative study of microsurgery and gamma knife radiosurgery in vestibular schwannoma evaluating tumor control and functional outcome. Neurooncol Adv 5(1):vdad146. 10.1093/noajnl/vdad146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tatagiba M, Ebner FH, Nakamura T, Naros G (2021) Evolution in surgical treatment of vestibular schwannomas. Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports 9(4):467–476. 10.1007/s40136-021-00366-2

- 16.Erickson NJ, Schmalz PGR, Agee BS et al (2019) Koos classification of vestibular schwannomas: a reliability study. Neurosurgery 85(3):409–414. 10.1093/neuros/nyy409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner G, Robertson JH (1988) Hearing preservation in unilateral acoustic neuroma surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 97(1):55–66. 10.1177/000348948809700110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollock BE, Lunsford LD, Kondziolka D et al (1995) Outcome analysis of acoustic neuroma management: a comparison of microsurgery and stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurg 36(1):215–224 discussion 224-9. 10.1227/00006123-199501000-00036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayhurst C, Zadeh G (2012) Tumor pseudoprogression following radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma. Neuro Oncol 14(1):87–92. 10.1093/neuonc/nor171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML et al (2009) The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 250(2):187–196. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Schober R, Vogeley KT, Urich H, Holzle E, Wechsler W (1992) Vascular permeability changes in tumours of the peripheral nervous system. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Histopathol 420(1):59–64. 10.1007/BF01605985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unger F, Walch C, Haselsberger K et al (1999) Radiosurgery of vestibular schwannomas: a minimally invasive alternative to microsurgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 141(12):1281–1285 discussion 1285-6. 10.1007/s007010050431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fundova P, Charabi S, Tos M, Thomsen J (2000) Cystic vestibular schwannoma: surgical outcome. J Laryngol Otol 114(12):935–939. 10.1258/0022215001904653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehrotra N, Behari S, Pal L, Banerji D, Sahu RN, Jain VK (2008) Giant vestibular schwannomas: focusing on the differences between the solid and the cystic variants. Br J Neurosurg 22(4):550–556. 10.1080/02688690802159031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Constanzo F, Teixeira BCA, Sens P, Ramina R (2019) Video head impulse test in vestibular schwannoma: relevance of size and cystic component on vestibular impairment. Otol Neurotol 40(4):511–516. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metwali H, Samii M, Samii A, Gerganov V (2014) The peculiar cystic vestibular schwannoma: a single-center experience. World Neurosurg 82(6):1271–1275. 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlson ML, Barnes JH, Nassiri A et al (2021) Prospective study of disease-specific quality-of-life in sporadic vestibular schwannoma comparing observation, radiosurgery, and microsurgery. Otol Neurotol 1(2):e199–e208. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollock BE, Driscoll CL, Foote RL et al (2006) Jul. Patient outcomes after vestibular schwannoma management: a prospective comparison of microsurgical resection and stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 59(1):77–85; discussion 77–85. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000219217.14930.14 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Carlson ML, Tveiten OV, Lund-Johansen M, Tombers NM, Lohse CM, Link MJ (2018) Patient motivation and long-term satisfaction with treatment choice in vestibular schwannoma. World Neurosurg 114:e1245–e1252. 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.03.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kent JA, Patel V, Varela NA (2012) Gender disparities in health care. Mt Sinai J Med 79(5):555–559. 10.1002/msj.21336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang SS, Bogli SY, Nierobisch N, Wildbolz S, Keller E, Brandi G (2022) Sex-related differences in patients’ characteristics, provided care, and outcomes following spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 37(1):111–120. 10.1007/s12028-022-01453-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding K, Ng E, Romiyo P et al (2020) Meta-analysis of tumor control rates in patients undergoing stereotactic radiosurgery for cystic vestibular schwannomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 188:105571. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirato M, Inoue H, Zama A, Ohye C, Shibazaki T, Andou Y (1996) Gamma knife radiosurgery for acoustic schwannoma: effects of low radiation dose and functional prognosis. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 66(Suppl 1):134–141. 10.1159/000099803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shirato H, Sakamoto T, Takeichi N et al (2000) Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for vestibular schwannoma (VS): comparison between cystic-type and solid-type VS. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1(5):1395–1401. 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00731-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charabi S, Mantoni M, Tos M, Thomsen J (1994) Cystic vestibular schwannomas: neuroimaging and growth rate. J Laryngol Otol 108(5):375–379. 10.1017/s0022215100126854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charabi S, Tos M, Thomsen J, Rygaard J, Fundova P, Charabi B (2000) Cystic vestibular schwannoma–clinical and experimental studies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 543:11–13. 10.1080/000164800453810-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthies C, Samii M, Krebs S (1997) Management of vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): radiological features in 202 cases–their value for diagnosis and their predictive importance. Neurosurg 40(3):469–481 discussion 481-2. 10.1097/00006123-199703000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jian BJ, Sughrue ME, Kaur R et al (2011) Implications of cystic features in vestibular schwannomas of patients undergoing microsurgical resection. Neurosurg 68(4):874–880 discussion 879–80. 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318208f614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang IP, Freeman SR, Rutherford SA, King AT, Ramsden RT, Lloyd SK (2014) Surgical outcomes in cystic vestibular schwannoma versus solid vestibular schwannoma. Otol Neurotol 35(7):1266–1270. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X, Song G, Wang X et al (2021) Comparison of surgical outcomes in cystic and solid vestibular schwannomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev 44(4):1889–1902. 10.1007/s10143-020-01400-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sottoriva A, Spiteri I, Piccirillo SG et al (2013) Intratumor heterogeneity in human glioblastoma reflects cancer evolutionary dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S 5(10):4009–4014. 10.1073/pnas.1219747110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang SY, Kim DG, Chung HT, Park SH, Paek SH, Jung HW (2008) Evaluation of tumour response after gamma knife radiosurgery for residual vestibular schwannomas based on MRI morphological features. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79(4):431–436. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.119602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pendl G, Ganz JC, Kitz K, Eustacchio S (1996) Acoustic neurinomas with macrocysts treated with gamma knife radiosurgery. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 66(Suppl 1):103–111. 10.1159/000099775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki H, Toyoda S, Muramatsu M, Shimizu T, Kojima T, Taki W (2003) Spontaneous haemorrhage into metastatic brain tumours after stereotactic radiosurgery using a linear accelerator. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74(7):908–912. 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.