Abstract

Background

Specific biomarkers for metabolic syndrome (MetS) may improve diagnostic specificity for clinical information. One of the main pathophysiological mechanisms of MetS is insulin resistance (IR). This systematic review aimed to summarize IR-related biomarkers that predict MetS and have been investigated in Iranian populations.

Methods

An electronic literature search was done using the PubMed and Scopus databases up to June 2022. The risk of bias was assessed for the selected articles using the instrument suggested by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). This systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42022372415).

Results

Among the reviewed articles, 46 studies investigated the association between IR biomarkers and MetS in the Iranian population. The selected studies were published between 2009 and 2022, with the majority being conducted on adults and seven on children and adolescents. The adult treatment panel III (ATP III) was the most commonly used criteria to define MetS. At least four studies were conducted for each IR biomarker, with LDL-C being the most frequently evaluated biomarker. Some studies have assessed the diagnostic potency of markers using the area under the curve (AUC) with sensitivity, specificity, and an optimal cut-off value. Among the reported values, lipid ratios and the difference between non-HDL-C and LDL-C levels showed the highest AUCs (≥ 0.80) for predicting MetS.

Conclusions

Considering the findings of the reviewed studies, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, leptin, HbA1c, and visfatin levels were positively associated with MetS, whereas adiponectin and ghrelin levels were negatively correlated with this syndrome. Among the investigated IR biomarkers, the association between adiponectin levels and components of MetS was well established.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40200-023-01347-6.

Keywords: Insulin, Insulin resistance, Lipid, Leptin, Adiponectin, Glycated hemoglobin, Ghrelin, Visfatin, Metabolic syndrome, Iran

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a non-communicable disease (NCD). It is characterized by abdominal obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridemia, low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and hypertension [1, 2], and increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke (2 folds) [3, 4], and type 2 diabetes (T2D) (3–20 folds) [5]. According to different definitions, its prevalence is increasing in various countries and is affected by significant factors such as age, sex, central obesity, ethnicity, and urbanization [6]. The worldwide prevalence of MetS ranges from 10 to 84% [7]. The prevalence of MetS is reported in the Middle East to be high in Pakistan (63%), followed by the United Arab Emirates (50%), Turkey (44%), Saudi Arabia (41%), Kuwait (36%), Qatar (33%), and 23% in Yemen [8]. Over the past two decades, its prevalence in Iran has been reported to be 34–42%, based on different MetS definitions [9–12].

The causes of MetS are complex and controversial. High-calorie intake promotes visceral adiposity, which could trigger many underlying mechanisms, such as increasing adiposity, causing more reactive oxygen species, and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to insulin resistance (IR) [13]. Oxidative stress, low-grade systemic inflammation, and IR appear to be critical factors in the development of MetS [14, 15].

Insulin resistance is the most widely accepted mechanism underlying the pathophysiology of MetS [15]. Insulin resistance, such as that in patients with diabetes, causes a pattern of atherogenic dyslipidemia in patients with MetS. This disrupts insulin-mediated inhibition of lipolysis in adipose tissue, thereby increasing free fatty acids. In addition, free fatty acids in the liver promote increased synthesis of glucose, triglycerides (TG), and apolipoprotein B. Other lipid abnormalities due to IR in individuals with MetS include increased TG levels, decreased HDL-C, increased small dense LDL, and small dense HDL particles [15–18]. Hence, evidence shows that many MetS components are controlled by IR [19]. However, the Mets diagnostic criteria did not include IR evaluation. The hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp is the gold standard for measuring IR; however, it is expensive and unavailable in all laboratories. Consequently, determining the concentrations of IR biomarkers can serve as an alternative method for measuring IR [20]. Lipids, lipid ratios, homeostatic model assessment for IR (HOMA-IR), leptin, adiponectin, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), ghrelin, and visfatin are common biomarkers of IR associated with MetS [7, 20, 21].

Biochemical markers are essential for diagnosing, developing, and treating MetS and other diseases [21]. Genetic markers, along with these markers, could predict the risk of MetS and further complications such as CVD and T2D [21–24]. However, the prediction models should be optimized for different ethnicities due to the varying levels of biochemical markers across populations [25]. However, measuring MetS biomarkers may enhance the diagnostic specificity of each individual and provide experts with relevant clinical information, resulting in improved personalized medicine for those affected by MetS [26]. Evaluating biochemical markers in diverse ethnic groups could provide a realistic picture of the associated markers and the major pathophysiological processes underlying MetS. To our knowledge, no review of MetS-associated biomarkers in the Iranian population has been conducted. This systematic review aimed to summarize the IR biomarkers that predict MetS and have been investigated in the Iranian population.

Methods

This systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO as CRD42022372415. Electronic literature on human studies was searched using the PubMed and Scopus databases in June 2022. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement was used as the reference protocol standard [27].

IR biomarkers that were MetS components according to most criteria were discarded. So, combinations of the following English-language keywords were used in the search for articles: “metabolic syndrome” (MeSH terms) AND “insulin resistance” (MeSH terms) AND “Iran” AND “biochemical markers” (MeSH terms) OR “Low-Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol” (MeSH terms) OR “Total Cholesterol” (MeSH terms) OR “TC/HDL-C” OR “TG/HDL-C” OR “LDL-C/HDL-C” OR “Insulin “(MeSH terms) OR “Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance” (MeSH terms) OR “Adiponectin” (MeSH terms) OR “Glycated hemoglobin” (MeSH terms) OR “Leptin” (MeSH terms) OR “Ghrelin” (MeSH terms) OR “Visfatin” (MeSH terms).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) studies investigating the association of IR biomarkers with MetS; (II) studies assessing biomarkers in the blood serum or plasma; (III) original published articles; all reviews, meta-analyses, clinical trials, interventions (nutrition and physical activity), animal studies, and unpublished studies or gray literature were excluded; and (IV) studies in which the outcome of MetS was investigated as the primary or secondary outcome alone, meaning that in the selected studies, a group of cases consisted of individuals with only MetS and no other disease.

Study selection

Data extraction

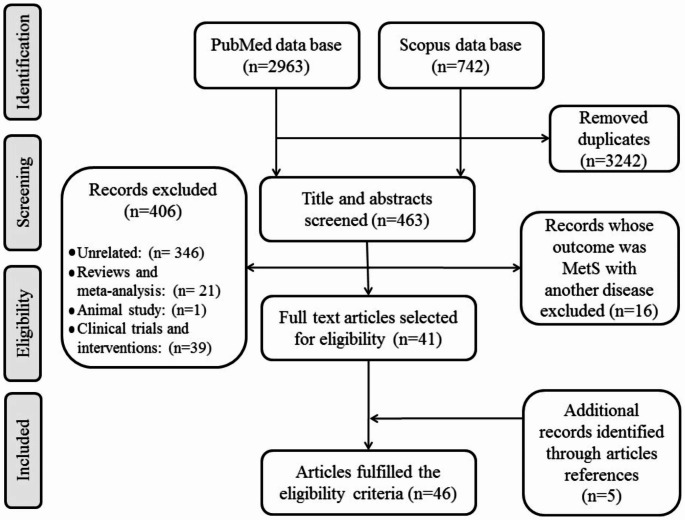

The method of study sorting was as follows: (1) EndNote tools removed duplicate articles; (2) two groups of authors were selected as reviewers; (3) all titles were screened to detect irrelevant studies; (4) abstracts and full texts of selected articles were read to extract biomarkers; and (5) to identify other potentially relevant articles, the reference lists of selected articles were observed and added. A flowchart of the study selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for literature selection

Data synthesis

To facilitate the analysis required for this review, we organized the data from the included studies in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. An additional file (spreadsheet) was then created from the initial spreadsheet, which contained the general characteristics of each study, such as the studied biomarkers, the number of study participants and their age and sex, the study’s MetS criteria, the main finding, the study population, author, and year of publication (Additional File 1).

Risk of bias assessment

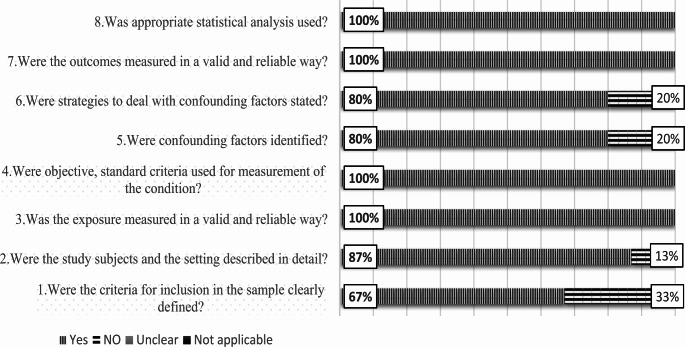

Using the instrument suggested by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), the risk of bias was assessed for the selected articles [28]. The evaluation was conducted using a checklist for cross-sectional analytical studies, which consists of eight queries that can be responded “yes,“ “no,“ “unclear,“ or “not applicable”. Yes, the responses showed a low risk of bias, whereas “no” responses indicated a high risk (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A summary, in percentages, of the overall risk of bias for the 46 studies that were included in the current systematic review

Results

Overview of studies identified

Among the 3705 reviewed documents, the association between IR biomarkers and MetS was investigated in the Iranian population in 46 studies. The maximum number of participants was 7284 [29], and the minimum was 73 [30]. Most studies were conducted on adults, seven on children and adolescents [30–36], and one on older women [37]. The adult treatment panel III (ATP III) was the most commonly used criteria to define MetS.

At least four studies were conducted for each IR biomarker, with LDL-C being the most frequently evaluated biomarker. The biomarkers are listed in Table 1 according to the number of studies in which they were evaluated, and the results of these studies are presented in the same manner in the following section. Some studies have evaluated the diagnostic potency of markers using the area under the ROC curve (AUC) with sensitivity, specificity, and, an optimal cut-off value (Table 2). For predicting MetS, lipid ratios and the difference between non-HDL-C and LDL-C levels showed the highest AUCs (0 ≥ 0.80) among the reported values.

Table 1.

Insulin resistance biomarkers related to MetS studied in the Iranian population

| Biomarkers | Subclass | Function | reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids | LDL-C | LDL-C is the main carrier of cholesterol in plasma. | [27, 30–32, 36–62] |

| TC | Cholesterol is a critical component of cell membranes since it contributes to the construction and regulates the membrane’s fluidity. | [27, 30–32, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41, 43–61] | |

| Lipid ratios | Lipid ratios may better reflect metabolic and clinical interactions between lipid fractions and supply information on risk variables that are difficult to measure by regular testing. | [29, 39, 48, 50, 51, 63, 64] | |

| Insulin | INS | Insulin hormone is required for glycaemic control, cell proliferation, and metabolism. | [31, 52, 54, 61] |

| HOMA-IR | HOMA-IR is an accepted method for quantifying insulin resistance. | [31, 40, 42, 54, 61, 66–68] | |

| Leptin | Another adipokine is involved in regulating insulin resistance. | [41, 67, 69–73] | |

| Adiponectin | Adiponectin is uniquely secreted from adipose tissue and enhances sensitivity to insulin and lipid metabolism | [34, 37, 59, 72, 74] | |

| Hemoglobin A1c | HbA1c is a useful marker for evaluating long-duration glycemic control in T2D patients. | [42, 46, 54, 55] | |

| Ghrelin | The growth hormone-secreting receptor is activated by ghrelin, a complex intestinal hormone. The main function of ghrelin is to increase appetite, fat storage, and growth hormone levels. | [30, 33, 61, 74] | |

| Visfatin | Visfatin is convincingly correlated to insulin resistance, which induces pro-inflammatory cytokines, like TNF-α and IL-6, in human monocytes | [28, 44, 54, 75] | |

LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, ; HDL-C, ; INS, insulin; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

Table 2.

The reported area under the ROC curve (AUC) of IR biomarkers for the diagnosis of MetS in Iranian studies

| Biochemical | AUC | 95% CI | Sensitivity | Specificity | Optimal cut-off value | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin | 0.73 | (0.65–0.81) | 73% | 61% | 5.75 (µg/ml)) | [72] |

| Adiponectin/leptin | 0.75 | (0.67–0.83) | 75% | 61% | 0.726 | [72] |

| Diff-C (ATP III criteria) | 0.80 | NR | 85% | 75% | 19.9 (mg/dl) | [29] |

| Diff-C (ATP III criteria) | 0.82 | (0.801, 0.838) | 73% | 83% | 29.55(mg/dL) | [76] |

| Diff-C (IDF criteria) | 0.78 | (0.757, 0.797) | 66% | 80% | 29.5(mg/dL) | [76] |

| HbA1c | 0.56 | NR | 25.30% | 82.60% | 5.6% | [55] |

| HOMA-IR (ATP III criteria) | 0.68 | (0.66–0.70) | 57% | 65% | 1.775 | [66] |

| HOMA-IR (IDF criteria) | 0.65 | (0.63–0.67) | 56% | 65% | 1.775 | [66] |

| HOMA-IR (JIS criteria in men) | 0.70 | (0.68–0.72) | 64% | 67% | 2 | [68] |

| HOMA-IR (JIS criteria in women) | 0.68 | (0.65–0.70) | 58% | 68% | 2.5 | [68] |

| LDL-C/ HDL-C (KERCARD criteria in men) | 0.73 | (0.71–0.75) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| LDL-C/ HDL-C (KERCARD criteria in women) | 0.74 | (0.72–0.76) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| LDL-C/ HDL-C (ATP III Criteria in men) | 0.69 | (0.67–0.72) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| LDL-C/ HDL-C (ATP III Criteria in women) | 0.73 | (0.72–0.75) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| Leptin | 0.66 | (0.57–0.75) | 67% | 64% | 8.1 (ng/ml) | [72] |

| Non-HDL-C (ATP III criteria) | 0.58 | NR | 44% | 73% | 120.5 (mg/dl) | [29] |

| Non-HDL-C (ATP III criteria) | 0.72 | (0.70–0.74) | 76% | 57% | 153.52 (mg/dL) | [76] |

| Non-HDL-C (IDF criteria) | 0.69 | (0.67–0.71) | 73% | 57% | 153.5 (mg/dL) | [76] |

| TC/HDL-C (KERCARD criteria) | 0.79 | (0.77–0.81) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| TC/HDL-C (ATP III Criteria in men) | 0.76 | (0.74–0.78) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| TC/HDL-C (ATP III Criteria in women) | 0.79 | (0.77–0.81) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| TG/HDL-C (ATP III Criteria in men) | 0.83 | (0.81–0.85) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| TG/HDL-C (ATP III Criteria in women) | 0.85 | (0.84–0.87) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| TG/HDL-C (ATP III criteria) | 0.81 | NR | 82% | 79% | 2.53 | [29] |

| TG/HDL-C (KERCARD criteria) | 0.85 | (0.84–0.87) | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| WC, BMI, SBP, TG/HDL-C, and matrix metalloproteinases-8 | 0.95 | (0.91–0.97) | 87.40% | 85.6% | NR | [29] |

ref, reference; Diff-C, difference between non-HDL-C and LDL-C; ATP III, adult treatment panel III; NR, not reported; IDF, international diabetes federation; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment for Insulin Resistance; JIS, Joint Interim Statement; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein; HDL-C, High-density lipoprotein; KERCARD, Kerman coronary artery disease risk factor study; TG, triglyceride; WC, waist circumference; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure

Figure 2 displays the critical evaluation results suggested by the JBI, with 89.4% of the selected papers receiving a “yes” response.

Lipids

Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C)

The association between LDL-C level and MetS has been extensively investigated in the Iranian population. Thirty-one studies (from 2009 to 2020) investigated the correlation between MetS and LDL-C levels in Iranian populations. Consistent with these findings, 20 studies have shown that MetS is associated with elevated LDL-C levels [29, 32, 38–55]. However, eleven investigations [33, 34, 56–64], including those with adolescent participants [33, 34], did not identify a significant association. Confounding factors were not included in assessing the association between LDL-C and MetS because, in most of these studies, determining this correlation was a secondary objective of the research. In just two studies, it was the main goal [48, 52]. Janghorbani et al. evaluated data from first-degree relatives of patients with T2D, both at baseline and after seven years. The unadjusted model demonstrated an association between LDL-C levels and the incidence and prevalence of MetS in both the longitudinal and cross-sectional analyses. After adjusting for age and fasting plasma glucose levels, the researchers found no association between baseline LDL-C levels and MetS. In addition, after adjusting for age and other MetS components, LDL-C levels could not predict MetS in a cohort of this high-risk Iranian population [48]. In a second study, Mohammadbeigi et al. investigated the correlation between LDL-C indicators and MetS without adjusting for factors such as age and MetS components. Thus, they concluded that fasting LDL-C values ≥ 160 mg/dL (OR = 2.05) were associated with MetS in addition to the components of the ATP III criteria [52]. The relationship between LDL-C levels and body mass index (BMI) or MetS components has not been studied to determine potential mechanisms associated with MetS.

Total cholesterol (TC)

Twenty-eight studies [29, 32–34, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 45–63] have investigated the correlation between TC levels and MetS in the Iranian population. Twenty-one studies showed a positive correlation between MetS and TC levels [29, 32, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 45–49, 51–57, 60, 62], whereas no significant relationship was found in other studies [33, 34, 50, 59, 63].

Total cholesterol is another lipid examined by Mohammadbeigi et al. In this study, continuous or classified TC levels had a significant positive relationship with MetS. The odds ratio for the relationship between TC and MetS in this study was the only one that was provided (OR = 1.80), and it was lower than the odds ratio for LDL-C (OR = 2.05) 52. Other studies have investigated the association between this marker and MetS as a secondary objective, primarily through descriptive tables and without controlling for confounding variables such as age and sex. The relationship between MetS components, or BMI and TC, has not been investigated in the Iranian population.

Lipids ratios

The association between lipids ratios and MetS was examined in seven surveys. In a study by Zarkesh et al. (2012), TC/HDL-C, TG/HDL-C, and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios were significantly associated with MetS in Tehran, Iran. Additionally, TC/HDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C were positively correlated with C-reactive protein (CRP), a key inflammatory marker associated with MetS [41]. Hosseini et al. (2015) reported a positive correlation between LDL-C/HDL-C and MetS in 180 non-diabetic employees of a company in Tehran [65]. Moreover, four studies in 2018 reported a positive relationship between MetS and the three lipid ratios in Iranian populations [31, 50, 52, 53]. Among the studies investigating the association between these three lipid ratios (TC/HDL-C, TG/HDL-C, and LDL-C/HDL-C) and MetS, only Rezapour et al. (2018) adjusted for age, sex, BMI, high blood pressure, and T2D. Therefore, the rising trend of the quartiles of all lipid ratios for both sexes was significantly correlated with MetS, as indicated by the adjusted odds ratios in this study. Rezapour et al. observed that TG/HDL-C had more substantial diagnostic power than LDL-C/HDL-C and TC/HDL-C in both sexes and various MetS criteria by evaluating the diagnostic abilities of lipid ratios based on AUC [53]. Mirmiran et al. (2019) found higher TG/HDL-C in three distinct groups of patients with hypertension, T2D, and MetS [66].

Rezapour et al. also examined the correlation between the lipid ratio and BMI and MetS components. With an increasing trend in lipid ratio quartiles, the mean BMI and MetS components increased significantly. HDL-C levels were significantly reduced in the upper quartiles of lipid ratios [53].

Insulin

Few studies have evaluated the correlation between insulin levels and MetS in the Iranian population. Three studies have reported that fasting insulin levels were higher in patients with MetS [54, 56, 63]. In contrast, one study reported reduced fasting insulin levels in obese individuals with MetS. However, Kelishadi et al. found no significant relationship between fasting insulin levels and MetS in a small sample of adolescents (n = 100) [33].

Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)

Most broad epidemiological studies have applied the HOMA-IR index, defined by Matthew et al. (HOMA-IR = fasting plasma insulin* fasting plasma glucose (FPG)/22.5) [67]. The correlation between HOMA-IR and MetS was also investigated in eight studies of the Iranian population [33, 42, 44, 56, 63, 68–70]. Among these studies, Esteghamati et al. (2009) indicated a correlation between HOMA-IR levels and MetS. Based on their report, HOMA-IR increased the risk of MetS (OR = 2.3) [69]. Other studies investigating the relationship between other biomarkers and MetS also reported a positive association between HOMA-IR and MetS [42, 44, 56, 63]. Klishadi et al. found no correlation between MetS and HOMA-IR in 100 adolescents [33]. The optimal HOMA-IR cut-off points for diagnosing MetS were determined by Esteghamati et al. (2010) using data from the third National Surveillance of Risk Factors of NCD in Iran (SuRFNCD-2007). In non-T2D patients, the optimal cut-off was 1.775 according to the ATP III and IDF MetS criteria [68]. This study found that in 3071 Iranians, the HOMA-IR AUC (95% CI) for MetS defined by IDF was 0.650, whereas the HOMA-IR AUC (95% CI) for MetS defined by ATP III was 0.683, and further adjustment for age and sex did not change the diagnostic accuracy for MetS by either definition [68]. In 2016, a similar study with 5511 people in Amol, Iran, found that the optimal cut-off point for HOMA-IR in men and women for MetS (according to the JIS definition) was 2.0 and 2.5, respectively. For men, the HOMA-IR AUC (95% CI) was 0.70 and for women, it was 0.68 [70].

In the first investigation by Esteghamati et al. (2009), HOMA-IR was associated with MetS components. These associations remained significant after controlling for age, sex, waist circumference (WC), and BMI, indicating their independence from obesity [69]. Although Esteghamati et al. (2010) found a direct correlation between the number of MetS components and HOMA-IR levels in their subsequent study, they did not examine the association between this marker and each component separately [68]. Likewise, in a study by Klishadi et al. on the adolescent population, a significant positive relationship was found between the higher quartile of HOMA-IR and the number of MetS components and TG levels, followed by WC, fat mass, and BMI. These relationships remained significant even after adjusting for age, sex, and pubertal status in the logistic regression analysis [33].

Leptin

The correlation between leptin and MetS was the subject of seven studies [43, 69, 71–75]. The leptin optimal cut-off values with IDF and ATP III criteria for MetS were 3.6 and 4.1 ng/ml in Iranian males, respectively; in women, it was equal to 11.0 ng/ml. The leptin cut-off value (regardless of sex) was comparable to the HOMA-IR cut-off value [72]. In candidate SNP (in the LEP gene) association studies, MetS patients had higher leptin levels [43], and elevated leptin levels were correlated with MetS components, including high TG and low HDL-C [43].

Moreover, it was reported that by increasing one unit in the number of MetS components, leptin rose by 1.87 fold, and obese individuals (regardless of whether or not they had MetS) had higher leptin levels [74]. Two case-control studies identified a positive correlation between serum leptin levels and obesity. In these studies, the case groups included participants with MetS who were overweight or obese, whereas the control groups included non-MetS patients with normal weight and those without MetS who were overweight or obese. Leptin levels were higher in the patients with MetS than in the control groups. Furthermore, in the control groups, obese individuals without MetS had elevated leptin levels compared with those with normal weight [71, 75]. Furthermore, another study showed that IR and MetS are correlated with elevated leptin levels, independent of BMI [69]. In the Tehran University of Medical Sciences study, the leptin/adiponectin ratio had a greater sensitivity for predicting MetS than adiponectin and leptin alone; however, the specificity of leptin was better [74].

Adiponectin

Six studies [36, 39, 56, 61, 74, 76] examined the relationship between adiponectin and MetS in the Iranian population. Two studies revealed no relationship between adiponectin levels and MetS [56, 76]. In contrast, Senjari et al. (2013) revealed a negative and independent relationship between adiponectin levels and MetS in women in Kerman after adjusting for age, BMI, and each component of MetS (β=-2,04) [39]. Moreover, a reverse correlation has also been detected in Iranian adolescents between MetS and adiponectin levels, independent of age, BMI, WC, and total cholesterol [36]. An age- and sex-matched study conducted in Gorgan revealed a negative correlation between MetS and adiponectin levels. The effect of other confounding variables, such as BMI, was not accounted for in this study’s analysis of this relationship [61]. Yosaee et al. (2019) indicated that plasma levels of adiponectin and adiponectin/leptin are negatively related to MetS independent of obesity in another age- and sex-matched study. Thus, the levels of these two indicators were lower in obese people with MetS than in obese and normal-weight metabolically healthy people [74]. They found that the optimal cut-off of adiponectin and adiponectin/leptin for diagnosing MetS was 5.75 g/ml and 0.726 g/ml, respectively; furthermore, adiponectin/leptin (AUC = 0.75) showed a slightly higher predictive power than adiponectin (AUC = 0.73) [74].

Based on the findings of various studies on the Iranian population, the level of adiponectin was negatively correlated with most components of MetS, including WC [36, 61, 74], TG [36, 39, 61, 74], fasting plasma glucose [36, 74], and SBP [36, 39, 74], and BMI [39, 74]. This marker was also positively correlated with HDL-C levels [36, 74].

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)

There was a positive correlation between HbA1c and MetS in four studies, all of which used case groups with only MetS and no T2D [44, 48, 56, 57]. Janghorbani and Amini estimated the multivariate-adjusted OR (95% CI) of MetS by increasing the highest quartile of HbA1c compared with the lowest quartile (OR = 2.01). Potential confounding factors of age, sex, BMI, WC, TG, LDL-C, HDL-C, TC, and SBP were adjusted. They also determined the optimal cut-off point of the biomarker for MetS detection (5.1 mg/dl) and suggested that HbA1c could be used as a component to predict MetS and could replace FPG [57]. Esteghamati et al. reported that, after visfatin level, HbA1c is the strongest predictor for MetS [56].

Ghrelin

The relationship between ghrelin and MetS was investigated in four studies of the Iranian population [32, 35, 63, 76]. Subjects with MetS had significantly lower ghrelin levels than the control population in Tabriz, Iran. In addition, ghrelin levels were inversely and significantly correlated with TG and fasting blood sugar (FBS) levels and positively correlated with HDL-C as MetS components [63]. Razzaghy-Azar et al. also showed that acyl-ghrelin is negatively associated with TG, LDL-C, insulin, HOMA-IR, and IR in Iranian children and adolescents. They found that acyl-ghrelin levels were significantly lower in obese individuals with MetS than in obese subjects without MetS [35]. A sample from the third survey of the Childhood and Adolescence Surveillance and Prevention of Adult Non-communicable Disease (CASPIAN-III) showed a similar result; a declining trend was observed in the mean ghrelin level with a rise in the number of MetS components [32]. However, the results of one investigation suggested no significant association between blood ghrelin levels and MetS [76].

Visfatin

Four studies examined the association between visfatin level and MetS [30, 46, 56, 77]. Esteghamati et al. revealed that among the markers HbA1c, LDL-C, creatinine, and adiponectin, visfatin was the best predictor for MetS. Their study showed a positive association between visfatin and MetS (OR = 1.32 for risk of MetS), which remained significant after adjustments for age, gender, waist and hip circumference, SBP and DBP, FPG, HbA1c, BMI, and HOMA-IR [56]. Visfatin levels were significantly higher in obese Iranian children and adolescents with MetS than those without MetS [30]. Samsam-Shariat et al. [46] concluded that serum visfatin levels were elevated in MetS patients, although this increase was insignificant. However, a negative correlation between visfatin level and MetS was demonstrated in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS) [77].

Discussion

In this systematic review, IR biomarkers of MetS were collected from studies conducted on the Iranian population. Except for ghrelin and adiponectin, the majority of studies found elevated levels of most markers in MetS. Ghrelin and adiponectin levels were found to be lower in patients with MetS compared to individuals without the condition. The TG/HDL-C ratio, other lipid ratios, the difference between non-HDL-C and LDL-C, and the adiponectin/leptin ratio had the highest reported AUC values for predicting MetS, as shown in Table 2 [31, 52, 74, 78].

The LDL-C particle comprises a cholesterol ester nucleus surrounded by apolipoprotein B. LDL-C is the primary carrier of cholesterol in the bloodstream [79]. Although elevated LDL-C levels are not a diagnostic component of MetS [16, 80], a considerable prevalence of elevated LDL-C has been observed among individuals with MetS in some countries, such as Nepal (64.4%) and Ethiopia (43.8%) [81]. Likewise, LDL-C levels were found to be an independent predictor of MetS, regardless of BMI or the five MetS components, in a screening investigation of a Japanese sample [82]. Insulin resistance has been found to reduce LDL-C receptor activity and slightly increase LDL-C levels [83]. However, the only study that examined the relationship between LDL-C levels and MetS, apart from obesity and MetS components, did not find this marker to be an independent predictor of MetS in the Iranian population [48]. Since the population studied in that research included first-degree relatives of diabetic patients, it is necessary to conduct studies on samples representing the entire population to check the predictive power of this marker.

Lipophilic cholesterol is transported in the blood via HDL, intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), LDL, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and chylomicron lipoproteins [84]. Like LDL-C, TC is not defined as a component of MetS [80]. However, some studies worldwide have revealed a positive and significant correlation between TC and MetS [17, 80, 85, 86]. On the other hand, IR has been associated with a high rate of cholesterol production and a low rate of cholesterol absorption [87]. Thus, IR may play a critical role in modulating the correlation between MetS and TC. In the Iranian population, a substantial number of investigations (21 studies) have confirmed this positive association. However, the predictive potential of this marker, as well as the impact of obesity and MetS components on this association, have not been investigated.

Lipid ratios are simple clinical indices that integrate information from multiple variables [88]. Studies have revealed the clinical usefulness of lipid ratios in identifying individuals with MetS in different population groups, such as American [89], Turkish [90], Korean [88, 91, 92], Ghanaian [93], Spanish [94], and multiethnic [95] populations. Among other lipid ratios, the TG/HDL-C ratio is more effective in diagnosing MetS in multiethnic, Spanish, and Korean children and adolescents [92], as well as in Iranian studies [31, 53, 62]. As stated in the study of Rezapour et al. [53], the fact that TG/HDL-C is a composite of two MetS components and indicates the amounts of both components simultaneously could be responsible for the ratio’s superior predictive efficacy. There has been no comparison between the predictive power of lipid biomarkers and their ratios for diagnosing MetS. Recent research has demonstrated that even after adjusting the analysis for waist circumference (WC), the TG/HDL-C ratio showed excellent and nearly identical predictive power for MetS in African-American patients [96]. Similarly, in the Iranian population, the positive correlation between MetS and the three lipid ratios (TC/HDL-C, TG/HDL-C, and LDL-C/HDL-C) was found to be independent of obesity and maintained after adjusting for BMI [53].

Insulin is an endocrine hormone that regulates body glucose homeostasis and has anabolic effects on protein and lipid metabolism [97]. Hyperinsulinemia responds to IR, and IR, or hyperinsulinemia, is a significant cause of MetS [98], so it has been suggested that MetS be renamed “insulin resistance syndrome” [99]. Additionally, in some definitions of MetS, such as the World Health Organization’s (WHO, 1998) criteria, IR is included as a component of MetS [100]. Fasting insulin alone accurately predicts IR [101, 102]. It has been demonstrated that the HOMA-IR index is a more accurate indicator of IR than fasting insulin levels [101]. MetS and its components and HOMA-IR were strongly and independently correlated in the majority of Iranian population studies. Only Klishadi et al. couldn’t find this correlation in 100 adolescents, likely due to the limited sample sizes in the four subgroups resulting from obesity and MetS conditions [33]. Two Iranian studies have determined the cut-off point of HOMA-IR in different groups. The optimal cut-off point of HOMA-IR for MetS ranged from 1.77 to 2.5 depending on the criteria of MetS and gender [68, 70], which was slightly lower and similar to some values calculated in other populations [103, 104]. In both studies, Youden’s index was used to determine the optimal HOMA-IR cutoff points for the diagnosis of MetS. Consequently, the greater values of the HOMA-IR cut-off to diagnose MetS found in the population of northern Iran might be attributed to variations in ethnicity, differences in MetS criteria, and the larger number of study samples [70].

Leptin is another adipokine involved in regulating IR [39, 73]. Elevated plasma leptin concentrations are associated with obesity, IR, myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure [105, 106]. In addition, different age and sex categories of MetS participants have also been found to have higher leptin levels [21]. Based on the reviewed studies, it can be concluded that leptin may be less specific for diagnosing MetS in obese individuals. This finding is entirely justified because adipose tissue is the primary source of leptin, and leptin levels are directly and strongly correlated with body fat mass [107]. Therefore, BMI-adjusted serum leptin levels can be considered a more robust biomarker than leptin for MetS detection in the Iranian population.

Adiponectin is an adipokine uniquely secreted from adipose tissue [108]. Serum adiponectin concentrations are associated with IR and some MetS components, such as enhancement of lipid oxidation [21, 39, 109, 110]. In a literature review, Falahi et al. (2015) concluded that adiponectin could be the most reliable biomarker for MetS diagnosis [111]. A significant and independent inverse relationship between MetS and adiponectin has been reported in various populations, including Finnish children and adolescents [112], Brazilian adolescents [113], Chinese adolescents [114], Puerto Rican adolescents [115], African American adults [116], Korean adults [117], and Dutch adults [118], which is consistent with the majority of studies in Iranian populations. Studies carried out in Iranian populations have also revealed a negative association between this adipokine and MetS and most of its components, except for two studies with small sample sizes [56, 76]. These results point to adiponectin as a possible treatment target for MetS and imply that monitoring circulating adiponectin levels might provide significant clinical information on the probability of developing MetS. Although the ratio of leptin to adiponectin has been shown to be a stronger predictor of MetS than each of these markers alone [111, 119], this ratio’s association with MetS has been investigated only in one study in the target population [74].

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) comprises glucose and other hexoses that bind to the valine of the hemoglobin β-chain [120]. HbA1c could be a helpful and straightforward clinical indicator for predicting IR [121]. Therefore, the possibility of replacing HbA1c with the glucose component in MetS criteria or including HbA1c as an extra component in the syndrome’s diagnosis has been explored in Iran and other populations [57, 122, 123]. Only one of the reviewed studies had as its primary objective the investigation of the relationship between this marker and MetS [57]; however, based on the results indicating a relationship between HbA1c and MetS independent of the components of MetS and BMI, as well as other studies in other populations, HbA1c can be considered a strong MetS biomarker.

Ghrelin is a hormone or cytokine produced mainly by gastric endocrine cells that control appetite, energy balance, and metabolism through the hypothalamus [124]. It also alters glucose metabolism and promotes IR and growth hormone release [125, 126]. Ghrelin administration increases free fatty acid concentrations and lipolysis [126]. The MetS and its components have been shown to have a strong negative relationship with ghrelin [127–130], and some studies have concluded that higher BMIs mainly explain this relationship in those with lower ghrelin levels [127, 131]. According to a review, low ghrelin levels are associated with obesity and hypertension, which are MetS components [21]. Consistent with the findings of these studies, three investigations in the Iranian population have also shown a negative correlation between ghrelin and acyl-ghrelin and MetS [32, 35, 63], although the strength of this correlation has not been measured.

Visfatin is an adipocyte hormone that convincingly correlates with IR and induces pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, in human monocytes [132]. The proven association of visfatin with IR suggests that, as an adipocytokine, it may play a role in the pathogenesis of MetS. However, there is still controversy regarding this [133]. The study by Esteghamati et al. [56] had a larger sample size and more accurate findings than the other studies in the current review, and its findings showed a strong, positive, and independent relationship between visfatin and MetS. Nevertheless, due to the contradictory results of other studies, additional research is required to establish the relationship between this hormone and MetS.

The primary limitations of the present study were the varying sample sizes and definitions of MetS among the studies, which made direct comparisons challenging. The lack of ROC curves in some studies limited the ability to compare the diagnostic potential of the biomarkers thoroughly.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of MetS biomarkers in the Iranian population and its ethnicities. Age- and race-specific biomarker panels should be developed and used to diagnose MetS [134, 135]. Focusing on a particular population may lead to a more accurate assessment to obtain correlated biomarkers, their diagnostic power, and the optimal cut-off point. The present study attempted to provide a narrative of all studies conducted on the Iranian population. Furthermore, we considered the mechanism of MetS biomarkers and focused on a group of biomarkers with IR as the primary pathophysiological process underlying MetS.

This review provides valuable insights into the associations between different biomarkers and MetS in the Iranian population. Further research is needed to determine optimal cutoff points for certain biomarkers such as LDL-C, TC, ghrelin, and visfatin and to explore additional markers, such as CRP/HDL-C [96], in the Iranian population.

Conclusion

According to studies on Iranian populations, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, leptin, HbA1c, and visfatin were positively associated with MetS, whereas adiponectin and ghrelin were negatively correlated with MetS. Lipid ratios, HOMA-IR, and the leptin/adiponectin ratio had the highest odds ratios and AUCs of ROC curves for diagnosing and predicting MetS among IR biomarkers. In various studies, the second aim was to consider the correlation between MetS and LDL-C as well as the association between MetS and TC. However, the majority of these studies did not adjust for obesity and MetS components, and the impact of them on this association needs further investigation. The relationship between LDL-C and MetS is still unclear, although some studies have found a positive correlation. Total cholesterol has shown a positive association with MetS in several studies. Among the IR biomarkers under investigation, the association between adiponectin levels and the components of MetS was the most well-established. According to the results of some reviewed research, the association between MetS and lipid ratios, HOMA-IR, adiponectin, HbA1c, and visfatin remained significant after controlling for BMI. HbA1c and HOMA-IR are strong biomarkers for MetS, independent of other components. While there is some controversy, one study showed a strong positive and independent relationship between visfatin and MetS.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was scientifically supported by the Research Institute of Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, I.R. Iran.

List of abbreviations

- ATP III

Adult treatment panel III

- AUC

The area under the ROC curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- FBS

Fasting blood sugar

- FPG

Fasting plasma glucose

- HbA1c

Glycated hemoglobin

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance

- IR

Insulin resistance

- IDL

Intermediate-density lipoprotein

- JIS

Joint interim statement

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein

- MetS

Metabolic syndrome

- NCD

Non-communicable disease

- ORs

Odd ratios

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- PRISMA

Systematic review and meta-analysis

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- T2D

Type 2 diabetes

- VLDL

Very low-density lipoprotein

Authors’ contributions

BS, AZ, and MD, study design; AZ, MZ, and BS, collected data from studies, reviewed the studies, and wrote the manuscript; MH, MD, and FA contributed to manuscript review, critical appraisal, and specialist advice. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was not supported by any funding agency.

Data availability

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huang PL. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2:231–7. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bovolini A, Garcia J, Andrade MA, Duarte JA. Metabolic syndrome pathophysiology and predisposing factors. Int J Sports Med. 2020;42:199–214. doi: 10.1055/a-1263-0898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guembe MJ, Fernandez-Lazaro CI, Sayon-Orea C, Toledo E, Moreno-Iribas C, et al. Risk for Cardiovascular Disease associated with metabolic syndrome and its components: a 13-year prospective study in the RIVANA cohort. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:195. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01166-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aschner P. Metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for Diabetes. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;8:407–12. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebrahimi H, Emamian MH, Shariati M, Hashemi H, Fotouhi A. Metabolic syndrome and its risk factors among middle aged population of Iran, a population based study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2016;10:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaur J. (2014) A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014: 943162. 10.1155/2014/943162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 8.Ansarimoghaddam A, Adineh HA, Zareban I, Iranpour S, HosseinZadeh A, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Middle-East countries: Meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azizi F, Hadaegh F, Hosseinpanah F, Mirmiran P, Amouzegar A, et al. Metabolic health in the Middle East and North Africa. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:866–79. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azizi F, Salehi P, Etemadi A, Zahedi-Asl S. (2003) Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an urban population: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 61: 29–37. https://doi.org/S0168822703000664. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Delavari A, Forouzanfar MH, Alikhani S, Sharifian A, Kelishadi R. First nationwide study of the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and optimal cutoff points of waist circumference in the Middle East: the national survey of risk factors for noncommunicable Diseases of Iran. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1092–7. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esmaillzadeh A, Mirmiran P, Azadbakht L, Etemadi A, Azizi F. High prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Iranian adolescents. Obes (Silver Spring) 2006;14:377–82. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed B, Sultana R, Greene MW. Adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;137:111315. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochlani Y, Pothineni NV, Kovelamudi S, Mehta JL. Metabolic syndrome: pathophysiology, management, and modulation by natural compounds. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;11:215–25. doi: 10.1177/1753944717711379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCracken E, Monaghan M, Sreenivasan S. Pathophysiology of the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duggan-Keen M. K-111: the emerging evidence for its potential in the treatment of the metabolic syndrome. Core Evid. 2006;1:169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta R, Deedwania PC, Gupta A, Rastogi S, Panwar RB, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an Indian urban population. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97:257–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daneshpour MS, Faam B, Mansournia MA, Hedayati M, Halalkhor S, et al. Haplotype analysis of apo AI-CIII-AIV gene cluster and lipids level: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Endocrine. 2012;41:103–10. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao Y, Kwon S, Shaughnessy S, Wallace P, Hutto A, et al. Critical evaluation of adult treatment panel III criteria in identifying insulin resistance with dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:978–83. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.4.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Son D-H, Ha H-S, Park H-M, Kim H-Y, Lee Y-J, C C New markers in metabolic syndrome. J A. 2022;110:37–71. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2022.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srikanthan K, Feyh A, Visweshwar H, Shapiro JI, Sodhi K. Systematic review of metabolic syndrome biomarkers: a panel for early detection, management, and risk stratification in the West Virginian population. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13:25. doi: 10.7150/ijms.13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moazzam-Jazi M, Najd Hassan Bonab L, Zahedi AS, Daneshpour MS. High genetic burden of type 2 Diabetes can promote the high prevalence of Disease: a longitudinal cohort study in Iran. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14006. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70725-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masjoudi S, Sedaghati-khayat B, Givi NJ, Bonab LNH, Azizi F, et al. Kernel machine SNP set analysis finds the association of BUD13, ZPR1, and APOA5 variants with metabolic syndrome in Tehran Cardio-metabolic Genetics Study. Sci Rep. 2021;11:10305. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89509-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonab LNH, Moazzam-Jazi M, Moosavi R-SM, Fallah M-S, Lanjanian H et al. (2021) Low HDL concentration in rs2048327-G carriers can predispose men to develop coronary heart disease: Tehran Cardiometabolic genetic study (TCGS). Gene. 778: 145485. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Lear SA, Gasevic D. Ethnicity and metabolic syndrome: implications for Assessment. Manage Prev Nutrients. 2019;12:15. doi: 10.3390/nu12010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landeck L, Kneip C, Reischl J, Asadullah K. Biomarkers and personalized medicine: current status and further perspectives with special focus on dermatology. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:333–9. doi: 10.1111/exd.12948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. JBI Evid Implement. 2015;13:147–53. doi: 10.1097/xeb.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mirhafez SR, Ebrahimi M, Saberi Karimian M, Avan A, Tayefi M, et al. Serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein as a biomarker in patients with metabolic syndrome: evidence-based study with 7284 subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1298–304. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nourbakhsh M, Nourbakhsh M, Gholinejad Z, Razzaghy-Azar M. Visfatin in obese children and adolescents and its association with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2015;75:183–8. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2014.1003594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angoorani P, Khademian M, Ejtahed H-S, Heshmat R, Motlagh ME, et al. Are non-high–density lipoprotein fractions associated with pediatric metabolic syndrome? The CASPIAN-V study. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17:257. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0895-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heshmat R, Shafiee G, Qorbani M, Azizi-Soleiman F, Djalalinia S, et al. Association of ghrelin with cardiometabolic risk factors in Iranian adolescents: the CASPIAN-III study. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2016;8:107–12. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2016.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelishadi R, Cook SR, Amra B, Adibi A. Factors associated with insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty Liver Disease among youths. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:538–43. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelishadi R, Qorbani M, Heshmat R, Motamed-Gorji N, Motlagh ME, et al. Association of alanine aminotransferase concentration with cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents: the CASPIAN-V cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2018;136:511–9. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2018.0161161118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Razzaghy-Azar M, Nourbakhsh M, Pourmoteabed A, Nourbakhsh M, Ilbeigi D, et al. An evaluation of Acylated Ghrelin and Obestatin Levels in Childhood Obesity and Their Association with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and oxidative stress. J Clin Med. 2016;5. 10.3390/jcm5070061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Shafiee G, Ahadi Z, Qorbani M, Kelishadi R, Ziauddin H, et al. Association of adiponectin and metabolic syndrome in adolescents: the caspian- III study. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:89. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0220-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakhtiari A, Hajian-Tilaki K, Omidvar S, Nasiri Amiri F. Association of lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status with metabolic syndrome in Iranian healthy elderly women. Biomed Rep. 2017;7:331–6. doi: 10.3892/br.2017.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashemi M, Kordi-Tamandani DM, Sharifi N, Moazeni-Roodi A, Kaykhaei MA, et al. Serum paraoxonase and arylesterase activities in metabolic syndrome in Zahedan, southeast Iran. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:219–22. doi: 10.1530/eje-10-0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanjari M, Khodashahi M, Gholamhoseinian A, Shokoohi M. Association of adiponectin and metabolic syndrome in women. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:1532–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghasemi A, Zahediasl S, Azizi F. High serum nitric oxide metabolites and incident metabolic syndrome. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2012;72:523–30. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2012.701322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zarkesh M, Faam B, Daneshpour MS, Azizi F, Hedayati M. The relationship between metabolic syndrome, cardiometabolic risk factors and inflammatory markers in a tehranian population: the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Intern Med. 2012;51:3329–35. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.8475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edalat B, Sharifi F, Badamchizadeh Z, Hossein-Nezhad A, Larijani B, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with inflammatory mediators in women with previous gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2013;12:8. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hassanzadeh T, Maleki M, Saidijam M, Paoli M. Association between leptin gene G-2548A polymorphism with metabolic syndrome. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:668–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Esteghamati A, Seyedahmadinejad S, Zandieh A, Esteghamati A, Gharedaghi MH, et al. The inverse relation of CA-125 to Diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and associated clinical variables. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11:256–61. doi: 10.1089/met.2012.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maleki A, Rashidi N, Aghaei Meybodi H, Montazeri M, Montazeri M, et al. Metabolic syndrome and inflammatory biomarkers in adults: a population-based survey in western region of Iran. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2014;8:156–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samsam-Shariat SZ, Bolhasani M, Sarrafzadegan N, Najafi S, Asgary S. Relationship between blood peroxidases activity and visfatin levels in metabolic syndrome patients. ARYA Atheroscler. 2014;10:218–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asgary S, SamsamShariat SZ, Ghorbani A, Keshvari M, Sahebkar A, et al. Relationship between serum resistin concentrations with metabolic syndrome and its components in an Iranian population. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2015;9:266–70. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janghorbani M, Amini M. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and metabolic syndrome in an Iranian high-risk population. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2015;9:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nejatinamini S, Ataie-Jafari A, Qorbani M, Nikoohemat S, Kelishadi R, et al. Association between serum uric acid level and metabolic syndrome components. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:70. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0200-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abbasian M, Delvarianzadeh M, Ebrahimi H, Khosravi F, Nourozi P. Relationship between serum levels of oxidative stress and metabolic syndrome components. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:497–500. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmadnezhad M, Arefhosseini SR, Parizadeh MR, Tavallaie S, Tayefi M, et al. Association between serum uric acid, high sensitive C-reactive protein and pro‐oxidant‐antioxidant balance in patients with metabolic syndrome. BioFactors. 2018;44:263–71. doi: 10.1002/biof.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohammadbeigi A, Farahani H, Moshiri E, Sajadi M, Ahmadli R, et al. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome and associations with lipid profiles in Iranian men: a Population-based screening program. World J Mens Health. 2018;36:50–6. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.17014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rezapour M, Shahesmaeili A, Hossinzadeh A, Zahedi R, Najafipour H, et al. Comparison of lipid ratios to identify metabolic syndrome. Arch Iran Med. 2018;21:572–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pouriamehr S, Barmaki H, Rastegary M, Lotfi F, Nabi Afjadi M. Investigation of insulin-like growth factors/insulin-like growth factor binding proteins regulation in metabolic syndrome patients. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:653. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4492-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghazizadeh H, Rezaei M, Avan A, Fazilati M, Pasdar A, et al. Association between serum cell adhesion molecules with hs-CRP, uric acid and VEGF genetic polymorphisms in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47:867–75. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-05081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Esteghamati A, Morteza A, Zandieh A, Jafari S, Rezaee M, et al. The value of visfatin in the prediction of metabolic syndrome: a multi-factorial analysis. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:541–6. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Janghorbani M, Amini M. Glycated hemoglobin as a predictor for metabolic syndrome in an Iranian population with normal glucose tolerance. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2012;10:430–6. doi: 10.1089/met.2012.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shahrokh S, Heydarian P, Ahmadi F, Saddadi F, Razeghi E. Association of inflammatory biomarkers with metabolic syndrome in hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2012;34:1109–13. doi: 10.3109/0886022x.2012.713280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mirhafez SR, Pasdar A, Avan A, Esmaily H, Moezzi A, et al. Cytokine and growth factor profiling in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:1911–9. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515001038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Afrand M, Khalilzadeh SH, Shojaoddiny-Ardekani A, Afkhami-Ardekani M, Ariaeinejad A. High frequency of metabolic syndrome in adult zoroastrians in Yazd, Iran: a cross-sectional study. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2016;30:370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sarbijani HM, Marjani A, Khoshnia M. The Association between metabolic syndrome and Serum Levels of Adiponectin and High Sensitive C reactive protein in Gorgan. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2016;16:107–12. doi: 10.2174/1871530315666150608123614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abbasian M, Delvarianzadeh M, Ebrahimi H, Khosravi F. Lipid ratio as a suitable tool to identify individuals with MetS risk: a case- control study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017;11(1):15–s19. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jabbari M, Kheirouri S, Alizadeh M. Decreased serum levels of ghrelin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in Premenopausal Women with metabolic syndrome. Lab Med. 2018;49:140–6. doi: 10.1093/labmed/lmx087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eshaghi FS, Ghazizadeh H, Kazami-Nooreini S, Timar A, Esmaeily H, et al. Association of a genetic variant in AKT1 gene with features of the metabolic syndrome. Genes Dis. 2019;6:290–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoseini SM, Kalantari A, Afarideh M, Noshad S, Behdadnia A, et al. Evaluation of plasma MMP-8, MMP-9 and TIMP-1 identifies candidate cardiometabolic risk marker in metabolic syndrome: results from double-blinded nested case-control study. Metabolism. 2015;64:527–38. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mirmiran P, Bahadoran Z, Tahmasebinejad Z, Azizi F, Ghasemi A. Circulating nitric oxide metabolites and the risk of cardiometabolic outcomes: a prospective population-based study. Biomarkers. 2019;24:325–33. doi: 10.1080/1354750X.2019.1567816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matthews D, Hosker J, Rudenski A, Naylor B, Treacher D, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Esteghamati A, Ashraf H, Khalilzadeh O, Zandieh A, Nakhjavani M, et al. Optimal cut-off of homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome: third national surveillance of risk factors of non-communicable Diseases in Iran (SuRFNCD-2007) Nutr Metab (Lond) 2010;7:26–6. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Esteghamati A, Khalilzadeh O, Anvari M, Rashidi A, Mokhtari M, et al. Association of serum leptin levels with homeostasis model assessment-estimated insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome: the key role of central obesity. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7:447–52. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Motamed N, Miresmail SJ, Rabiee B, Keyvani H, Farahani B, et al. Optimal cutoff points for HOMA-IR and QUICKI in the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty Liver Disease: a population based study. J Diabetes Complications. 2016;30:269–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bitarafan V, Esteghamati A, Azam K, Yosaee S, Djafarian K. Comparing serum concentration of spexin among patients with metabolic syndrome, healthy overweight/obese, and normal-weight individuals. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2019;33:93. doi: 10.34171/mjiri.33.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Esteghamati A, Zandieh A, Zandieh B, Khalilzadeh O, Meysamie A, et al. Leptin cut-off values for determination of metabolic syndrome: third national surveillance of risk factors of non-communicable Diseases in Iran (SuRFNCD-2007) Endocrine. 2011;40:117–23. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakhjavani M, Esteghamati A, Tarafdari AM, Nikzamir A, Ashraf H, et al. Association of plasma leptin levels and insulin resistance in diabetic women: a cross-sectional analysis in an Iranian population with different results in men and women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27:14–9. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.487583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yosaee S, Khodadost M, Esteghamati A, Speakman JR, Djafarian K, et al. Adiponectin: an Indicator for metabolic syndrome. Iran J Public Health. 2019;48:1106–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yosaee S, Khodadost M, Esteghamati A, Speakman JR, Shidfar F, et al. Metabolic syndrome patients have lower levels of adropin when compared with healthy overweight/obese and lean subjects. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11:426–34. doi: 10.1177/1557988316664074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hajmohammadi T, Sadeghi M, Dashti M, Hashemi M, Saadatnia M, et al. Relationship between carotid intima-media thickness with some inflammatory biomarkers, Ghrelin and Adiponectin in iranians with and without metabolic syndrome in Isfahan Cohort Study. ARYA Atheroscler. 2010;6:56–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hosseinzadeh-Attar MJ, Golpaie A, Foroughi M, Hosseinpanah F, Zahediasl S, et al. The relationship between visfatin and serum concentrations of C-reactive protein, interleukin 6 in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2016;39:917–22. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ghodsi S, Meysamie A, Abbasi M, Ghalehtaki R, Esteghamati A, et al. Non-high-density lipoprotein fractions are strongly associated with the presence of metabolic syndrome Independent of obesity and Diabetes: a population-based study among Iranian adults. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2017;16:25. doi: 10.1186/s40200-017-0306-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fan J, Liu Y, Yin S, Chen N, Bai X, et al. Small dense LDL cholesterol is associated with metabolic syndrome traits independently of obesity and inflammation. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2019;16:7–7. doi: 10.1186/s12986-019-0334-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee W-J, Huang M-T, Wang W, Lin C-M, Chen T-C, et al. Effects of obesity Surgery on the metabolic syndrome. JAMA Surg. 2004;139:1088–92. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.10.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Adnan E, Rahman IA, Faridin H. Relationship between insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome components and serum uric acid. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:2158–62. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oda E, J I M. .(2013) Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is a predictor of metabolic syndrome in a Japanese health screening population. 52: 2707–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.Cho Y, Lee S-G, Jee SH, Kim J-H. Hypertriglyceridemia is a major factor Associated with elevated levels of small dense LDL cholesterol in patients with metabolic syndrome. alm. 2015;35:586–94. doi: 10.3343/alm.2015.35.6.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huff T, Boyd B, Jialal IJS. Physiology, cholesterol. 2021. [PubMed]

- 85.Ogbera AO. Prevalence and gender distribution of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Takeuchi H, Saitoh S, Takagi S, Ohnishi H, Ohhata J, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cardiac Disease in Japanese men: applicability of the concept of metabolic syndrome defined by the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III to Japanese men–the Tanno and Sobetsu Study. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:203–8. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pihlajamäki J, Gylling H, Miettinen TA, Laakso MJ, J o l r Insulin resistance is associated with increased cholesterol synthesis and decreased cholesterol absorption in normoglycemic men. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:507–12. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300368-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kimm H, Lee SW, Lee HS, Shim KW, Cho CY, et al. Associations between lipid measures and metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and adiponectin: usefulness of lipid ratios in Korean men and women. Circ J. 2010;74:931–7. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jialal I, Adams-Huet B, J E, R The ratios of triglycerides and C-reactive protein to high density-lipoprotein-cholesterol as valid biochemical markers of the nascent metabolic syndrome. Endocr Res. 2021;46:196–202. doi: 10.1080/07435800.2021.1930039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Onat A, Can G, Kaya H, Hergenç G. Atherogenic index of plasma (log10 triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol) predicts High Blood Pressure, Diabetes, and vascular events. J Clin Lipidol. 2010;4:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim SW, Jee JH, Kim HJ, Jin S-M, Suh S, et al. Non-HDL-cholesterol/HDL-cholesterol is a better predictor of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance than apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A1. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2678–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee J, Ah Lee Y, Yong Lee S, Ho Shin C, Hyun Kim J. Comparison of lipid-derived markers for metabolic syndrome in Youth: Triglyceride/HDL cholesterol ratio, triglyceride-glucose index, and non-HDL cholesterol. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2022;256:53–62. doi: 10.1620/tjem.256.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Arthur FK, Adu-Frimpong M, Osei-Yeboah J, Mensah FO, Owusu LJL, i H, et al. Prediction of metabolic syndrome among postmenopausal Ghanaian women using obesity and atherogenic markers. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cordero A, Laclaustra M, León M, Casasnovas JA, Grima A, et al. Comparison of serum lipid values in subjects with and without the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:424–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gasevic D, Frohlich J, Mancini G, Lear S, A J, L i h. and disease.(2014) Clinical usefulness of lipid ratios to identify men and women with metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis 13: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Jialal I, Adams-Huet B. The ratios of triglycerides and C-reactive protein to high density-lipoprotein -cholesterol as valid biochemical markers of the nascent metabolic syndrome. Endocr Res. 2021;46:196–202. doi: 10.1080/07435800.2021.1930039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rahman MS, Hossain KS, Das S, Kundu S, Adegoke EO, et al. Role of insulin in Health and Disease: an update. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. 10.3390/ijms22126403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Kelly CT, Mansoor J, Dohm GL, Chapman IVJR, III, et al. Hyperinsulinemic syndrome: the metabolic syndrome is broader than you think. Surgery. 2014;156:405–11. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Balkau B. (1999) Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Diabet med. 16: 442–443. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Alberti K G M M, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lee S, Choi S, Kim HJ, Chung Y-S, Lee KW et al. (2006) Cutoff values of surrogate measures of insulin resistance for metabolic syndrome in Korean non-diabetic adults. Jkms. 21: 695–700. 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.4.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.McAuley KA, Williams SM, Mann JI, Walker RJ, Lewis-Barned NJ, et al. Diagnosing insulin resistance in the general population. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:460–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gayoso-Diz P, Otero-González A, Rodriguez-Alvarez MX, Gude F, García F, et al. Insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) cut-off values and the metabolic syndrome in a general adult population: effect of gender and age: EPIRCE cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2013;13:47. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-13-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lin S-Y, Li W-C, Yang T-A, Chen Y-C, Yu W, et al. Optimal threshold of Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance to identify metabolic syndrome in a Chinese Population aged 45 years or younger. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;12. 10.3389/fendo.2021.746747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 105.Ghantous CM, Azrak Z, Hanache S, Abou-Kheir W, Zeidan A. (2015) Differential Role of Leptin and Adiponectin in Cardiovascular System. Int J Endocrinol. 2015: 534320. 10.1155/2015/534320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 106.Moazzam-Jazi M, Sadat Zahedi A, Akbarzadeh M, Azizi F, Daneshpour MS. Diverse effect of MC4R risk alleles on obesity-related traits over a lifetime: evidence from a well-designed cohort study. Gene. 2022;807:145950. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2021.145950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cui H, López M, Rahmouni K. The cellular and molecular bases of leptin and ghrelin resistance in obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:338–51. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bakhai A. (2008) Adipokines–targeting a root cause of cardiometabolic risk. QJM. 101: 767–76. 10.1093/qjmed/hcn066. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 109.Tehrani FR, Daneshpour M, Hashemi S, Zarkesh M, Azizi F J I J o R, M Relationship between polymorphism of insulin receptor gene, and adiponectin gene with PCOS. Iran J Reprod Med. 2013;11:185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zahedi AS, Daneshpour MS, Akbarzadeh M, Hedayati M, Azizi F et al. (2023) Association of baseline and changes in adiponectin, homocysteine, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10 levels and metabolic syndrome incidence: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Heliyon. 9: e19911. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Falahi E, Khalkhali Rad AH, Roosta S. What is the best biomarker for metabolic syndrome diagnosis? Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2015;9:366–72. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Juonala M, Saarikoski LA, Viikari JSA, Oikonen M, Lehtimäki T, et al. A longitudinal analysis on associations of adiponectin levels with metabolic syndrome and carotid artery intima-media thickness. Cardiovasc Risk Young Finns Study Atherosclerosis. 2011;217:234–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sparrenberger K, Sbaraini M, Cureau FV, Teló GH, Bahia L, et al. Higher adiponectin concentrations are associated with reduced metabolic syndrome risk independently of weight status in Brazilian adolescents. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2019;11:40. doi: 10.1186/s13098-019-0435-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Li P, Jiang R, Li L, Liu C, Yang F, et al. Correlation of serum adiponectin and adiponectin gene polymorphism with metabolic syndrome in Chinese adolescents. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:62–7. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Guseman EH, Eisenmann JC, Laurson KR, Cook SR., and Stratbucker W J A p.(2018) calculating a continuous metabolic syndrome score using nationally representative reference values. Acad Pediatr 18: 589–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 116.Khan RJ, Gebreab SY, Sims M, Riestra P, Xu R, et al. Prevalence, associated factors and heritabilities of metabolic syndrome and its individual components in African americans: the Jackson Heart Study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008675. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kim J-Y, Ahn SV, Yoon J-H, Koh S-B, Yoon J, et al. Prospective study of serum adiponectin and incident metabolic syndrome: the ARIRANG study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1547–53. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hajer GR, van der Graaf Y, Olijhoek JK, Verhaar MC, Visseren FL. Levels of homocysteine are increased in metabolic syndrome patients but are not associated with an increased cardiovascular risk, in contrast to patients without the metabolic syndrome. Heart. 2007;93:216–20. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.093971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gasevic D, Frohlich J, Mancini GJ, Lear S, A J L i h, and disease Clinical usefulness of lipid ratios to identify men and women with metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:159. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-13-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mahajan RD, Mishra B. Using glycated hemoglobin HbA1c for diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus: an Indian perspective. Int J Biol Med Res. 2011;2:508–12. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Saha S, Schwarz PE. Impact of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) on identifying insulin resistance among apparently healthy individuals. J Public Health. 2017;25:505–12. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ong KL, Tso AW, Lam KS, Cherny SS, Sham PC, et al. Using glycosylated hemoglobin to define the metabolic syndrome in United States adults. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1856–8. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Park SH, Yoon JS, Won KC, Lee HW. Usefulness of glycated hemoglobin as diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:1057–61. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.9.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pereira JA, d S, Silva FC, d, de Moraes-Vieira PMM. (2017) The Impact of Ghrelin in Metabolic Diseases: An Immune Perspective. J Diabetes Res. 2017: 4527980. 10.1155/2017/4527980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 125.Kim S, Nam Y, Shin SJ, Park YH, Jeon SG, et al. The potential roles of Ghrelin in metabolic syndrome and secondary symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.583097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Vestergaard ET, Jessen N, Møller N, Jørgensen, J O, L Acyl ghrelin induces insulin resistance independently of GH, cortisol, and free fatty acids. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42706. doi: 10.1038/srep42706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Langenberg C, Bergstrom J, Laughlin GA, Barrett-Connor E. Ghrelin and the metabolic syndrome in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6448–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Broglio F, Gottero C, Prodam F, Gauna C, Muccioli G, et al. Non-acylated ghrelin counteracts the metabolic but not the neuroendocrine response to Acylated Ghrelin in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3062–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ukkola O, Pöykkö SM, Antero Kesäniemi, Y J A o m Low plasma ghrelin concentration is an indicator of the metabolic syndrome. Ann Med. 2006;38:274–9. doi: 10.1080/07853890600622192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ukkola OJCP, Science P. (2009) Ghrelin and metabolic disorders. 10: 2–7. [DOI] [PubMed]