Abstract

Foamy viruses (FVs) are highly fusogenic, and their replication induces massive syncytium formation in infected cell cultures which is believed to be mediated by expression of the envelope (Env) protein. The FV Env is essential for virus particle egress. The unusually long putative membrane-spanning domain (MSD) of the transmembrane subunit carries dispersed charged amino acids and has an important function for particle envelopment. To better understand the capsid-envelope interaction and Env-mediated cell fusion, we generated a variety of FV MSD mutations. C-terminal deletions revealed the cytoplasmic domain to be dispensable but the full-length MSD to be required for fusogenic activity. The N-terminal 15 amino acids of the MSD were found to be sufficient for membrane anchorage and promotion of FV particle release. Expression of wild-type Env protein rarely induced syncytia due to intracellular retention. Coexpression with FV Gag-Pol resulted in particle export and a dramatic increase in fusion activity. A nonconservative mutation of K959 in the middle of the putative MSD resulted in increased fusogenic activity of Env in the absence of Gag-Pol due to enhanced cell surface expression as well as structural changes in the mutant proteins. Coexpression with Gag-Pol resulted in a further increase in the fusion activity of mutant FV Env proteins. Our results suggest that an interaction between the viral capsid and Env is required for FV-induced giant-cell formation and that the positive charge in the MSD is an important determinant controlling intracellular transport and fusogenic activity of the FV Env protein.

Glycoproteins of enveloped viruses mediate binding to the host cell and delivery of capsids to the cytoplasm by fusing virion and cellular lipid membranes. For retroviruses, binding to the cellular receptor is mediated by the surface (SU) subunit of the Env protein, whereas the fusion of the lipid membranes involves mainly the transmembrane (TM) subunit. The latter mechanism has been best studied for the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) protein (3, 4, 5). Recent studies on retroviral Env proteins suggest some homology to HA at both the structural and the functional level (20, 34). For the human (HIV) and simian immunodeficiency viruses, murine leukemia virus (MuLV), and Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV), the fusion activity of Env proteins was found to be regulated by the cytoplasmic domain (CyD) (2, 24, 28, 29). In the cases of MuLV and MPMV, the Env CyD contains a C-terminal inhibitory domain that is cleaved during or shortly after budding by the viral proteinase, thereby transferring the Env protein into a fusogenic conformation (2, 28). For HIV Env, which contains an extraordinarily long CyD, cleavage of the CyD is not observed. However, the C-terminal portion of the CyD also controls the fusion activity, as artificial CyD truncations rendered the shortened mutants highly fusogenic (24, 29). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the membrane-spanning domains (MSDs) of these retroviral Env proteins are critical for the fusion process, as mutations of the MSD affected fusion activity (18, 25, 27).

Foamy viruses (FVs) make up a separate group in the class of Retroviridae. As indicated by their name, FVs are highly fusogenic upon replication in most cell cultures. The replication strategy of FVs shows several unique features not found for any other retrovirus and bears some resemblance to that of the Hepadnaviridae (for a review, see reference 23). A specialty with respect to their Env protein is the strict requirement for coexpression of Env and Gag for the budding and viral particle release process (1, 9, 32). Two alternatively spliced forms of the FV Env protein are detected; however, at least in vitro, only the gp130 form is required for viral replication (12, 22). This form of the FV Env protein contains an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retrieval signal at the C terminus of the CyD (15). Inactivation of this signal leads to increased syncytium formation, most probably as a result of increased Env transport to the cell surface (14). However, we and others have shown that the ER retrieval signal and the CyD of Env are dispensable for infectivity and in vitro replication (13, 26). Furthermore, we found previously that the putative MSD of the FV TM subunit plays an important role for virus particle egress and cannot be replaced by alternative forms of membrane anchorage or heterologous domains of other retroviral Env proteins (26). In the present study, we analyzed the role of the putative MSD and CyD in regulation of FV Env protein fusion activity and dissected the function of the MSD for particle release in further detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression constructs.

The eukaryotic expression constructs for various FV envelope mutants depicted in Fig. 1 are based on the previously described pcHFE-wt plasmid (EM02 mutation), which expresses only gp130 due to inactivation of the internal splice donor and splice acceptor pair within the FV Env coding region (22, 26). All point mutations within the MSD (pcHFVenv EM21 through EM30, as described below) were generated by recombinant PCR techniques (19) using primers introducing the respective codon changes. The PCR products were cloned into the pcHFE-wt plasmid as NheI-EcoRI fragments, and the inserts were completely sequenced to verify the desired sequence and to exclude further mutations. In the mutant envelope proteins, the conserved, positively charged lysine residue at position 959 of the amino acid sequence was replaced conservatively (EM27, arginine), replaced with a hydrophobic residue (EM21 and EM30, alanine and leucine, respectively), or replaced with a negatively charged amino acid (EM28 and EM29, glutamic acid and aspartic acid, respectively). A mutation of the conserved proline at position 960 to alanine was introduced (EM22), or a double mutation of the lysine-proline motif to two alanines was created (EM23). Additionally, a deletion mutant was designed that is truncated at amino acid 960 (EM31). This deletion mutant was generated by inserting an NheI-EcoRI PCR insert with a premature stop codon into pcHFE-wt. Furthermore, several previously described deletion mutants were included in this study: pcHFE-1, truncated at residue 981; pcHFE-2, truncated at amino acid 975; and pcHFE-3Pi, which contains the FV Env ectodomain fused to the phosphoglycolipid (GPI) anchor signal sequence derived from the human placental alkaline phosphatase protein (26).

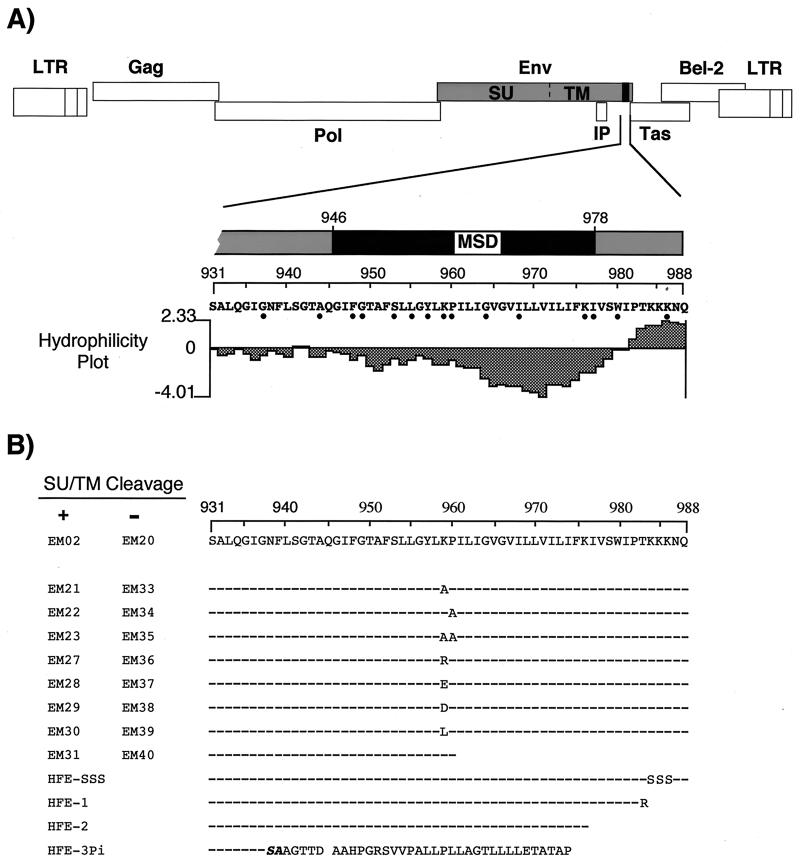

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the FV MSD and artificial amino acid changes. (A) Organization of the FV genome and enlarged C-terminal region of the Env protein containing the putative MSD and CyD. LTR, long terminal repeat; IP, internal promoter. The dots below the sequence indicate conserved amino acids in all known FV isolates. A hydrophilicity plot of this region of the FV Env protein according to Kyte-Doolittle generated by the Protean program (DNASTAR software) is shown below. (B) Amino acid sequence of the individual FV mutants described in this study. The designations indicate whether the mutants are based on the wild-type sequence (+) or the mutant EM20 (R571T), in which the SU/TM cleavage site is inactivated (−). Dashes represent amino acids that are identical to those in the wild-type sequence (EM02).

In order to study Env functions independently of fusion activity, we created several mutants in which SU-TM cleavage was abolished. In EM20, R571 was altered to T571, a mutation found previously to inactivate SU-TM cleavage in HIV-1 Env (11). The mutant PCR product was inserted into the StuI and BsrGI restriction sites of plasmid pcHFE-wt. Constructs EM33 through EM40 were created by cloning NheI-EcoRI fragments from the MSD mutants EM21 through EM31 into the EM20 construct, which hence harbors both the SU-TM cleavage site and the MSD mutations.

The replication-deficient FV proviral construct pDL01 is based on the FV vector pMH4 (17), expressing the Gag-Pol and Env proteins from a chimeric cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter-FV promoter and an enhanced green fluorescent protein-neo fusion (EGFP-Neo) from an internal spleen focus-forming virus U3 promoter. pDL01 contains the EM02 mutation (22) described above and additional BsmBI and EcoRI restriction sites upstream and downstream of the Env open reading frame (ORF), respectively, to facilitate exchange of various portions of the FV Env ORF. The BsmBI restriction site was introduced by a silent mutation so that the overlapping pol ORF remained unaltered. The individual Env mutations were introduced into pDL01 as NheI-EcoRI fragments from the pcHFVenv expression constructs.

The replication-deficient pMH62 vector was described previously (26). It expresses the FV Gag-Pol proteins and contains the internal spleen focus-forming virus U3 promoter-directed EGFP marker gene expression cassette.

Generation of recombinant FV supernatants and viral infectivity assay.

Supernatants containing viruses with the different recombinant envelopes were generated by transfection of 293T cells (7) with vector pMH62 and the envelope expression constructs essentially as described earlier (9, 21, 22). The infectivity of the Env mutants was analyzed following transfection of 293T cells with pDL01 constructs and transduction of recipient HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells with cell supernatant as described previously (17, 21) except that the amount of particle-associated Gag proteins was determined by Western blotting and quantitated by densitometry. The relative infectivity was then normalized for the Gag content in the cell supernatant.

RIPA.

For the radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA), transiently transfected 293T cells were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine for approximately 20 h. The cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 0.3 M NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) containing protease inhibitors. Viral proteins were precipitated as described earlier (9, 22) with rabbit antisera directed against recombinant FV proteins and specific for Env (22) and Gag (16). Particle-associated proteins were detected after centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion as described previously (9, 22).

Cell fusion assay.

The fusion activity of the different envelope mutants was analyzed using a cell-to-cell fusion assay. 293T cells were transiently transfected with the envelope expression constructs and/or the FV vector pMH62. Empty expression vector (pCDNA3.1+zeo) was used to adjust the amount of transfected DNA to 15 μg total. At 24 h following transfection, the cells were detached from the tissue culture plates, mixed at a ratio of 1:1 with HT1080 human fibrosarcoma target cells stably expressing a beta-galactosidase marker protein with a nuclear localization signal (NLS), and reseeded. Syncytia were allowed to form overnight. Subsequently, cells were fixed and histochemically stained as described previously (31). Fusion activity was quantified by counting syncytia containing more than four nuclei in five independent fields of view at a magnification of ×125. The sensitivity of the assay could be increased by longer cocultivation of the Env-expressing cells and the fusion partners and simultaneous induction of CMV-driven gene expression by treatment with 10 mM sodium butyrate, resulting in about 10-fold-higher values for the weakly fusogenic mutants. The HT1080 NLS-lacZ cell line was generated by infection of HT1080 cells with an MuLV-based retroviral vector (SFG NLS-lacZ) (30) and subsequent subcloning by limiting dilution.

Surface biotinylation assay.

Transiently transfected 293T cells were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine for approximately 20 h. At 36 h after addition of the DNA, cell surface protein was labeled with NHS-Biotin (Calbiochem) at 1 mg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min. Subsequently, the biotinylation reaction was stopped by adding PBS containing 100 mM glycine prior to cell lysis in RIPA buffer. Lysates were precipitated with an FV-positive chimpanzee serum as described earlier (9, 22), separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted on nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL; Amersham). Envelope protein expression at the cell surface was analyzed by using streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Pierce), followed by detection by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Amersham). The chemoluminescent biotin signal was allowed to fade overnight. Thereafter, the blot was exposed to X-ray film, and total cellular envelope expression was detected by autoradiography.

RESULTS

Design of MSD mutations.

As found for primate lentiviruses, one feature of the FV Env protein is an extremely long putative MSD, as proposed previously (10, 33). Comparison of the amino acid sequences of all known FV isolates reveals a clustering of several evolutionarily conserved amino acids in the first half of this region of the FV Env protein (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, in the middle of the putative MSD, a charged lysine residue followed by a proline residue, known as a helix breaker, can be found. This is quite unusual for an MSD, which is thought to adopt an α-helical conformation. To analyze the role of these two conserved residues in the function of FV Env protein in the FV replication cycle, we generated several point mutants. Furthermore, a truncation mutant terminating immediately after P960 was generated, removing the C-terminal half of the putative MSD and the CyD. The individual mutants are depicted in Fig. 1B.

Influence of MSD mutants on FV particle release.

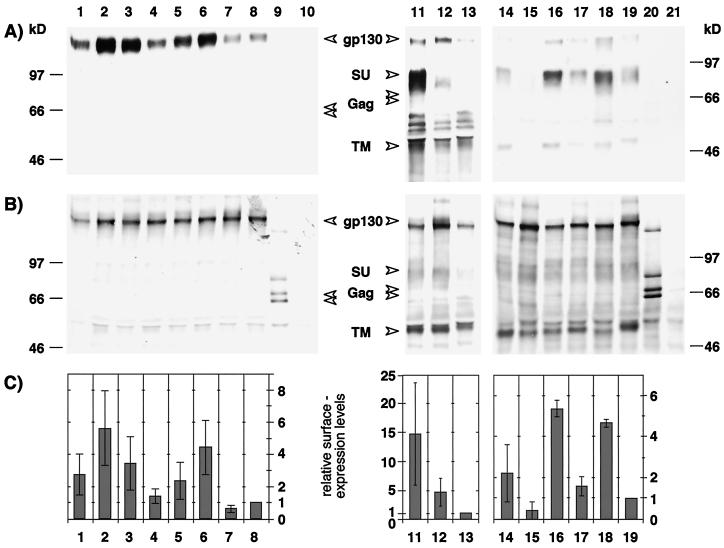

To analyze the effect of the deletion mutation and the K959 and P960 point mutations on FV particle release, 293T cells were cotransfected with the individual Env expression plasmids and the Gag-Pol-encoding FV vector pMH62. All mutants were expressed intracellularly at similar levels (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 to 10), and FV particle egress was only reduced significantly by the P960A mutation in EM22 and EM23 (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 2 and 3). All K959 single mutants released FV particles at levels similar to or higher than those of the wild-type protein (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 1 and 4 to 7). Interestingly, the EM31 truncation mutant containing only the N-terminal 15 amino acids of the putative MSD was still able to support FV particle release (Fig. 2B and C, lane 8). The Env/Gag ratio of the different particles was within a twofold range (Fig. 2D, lanes 1 to 9).

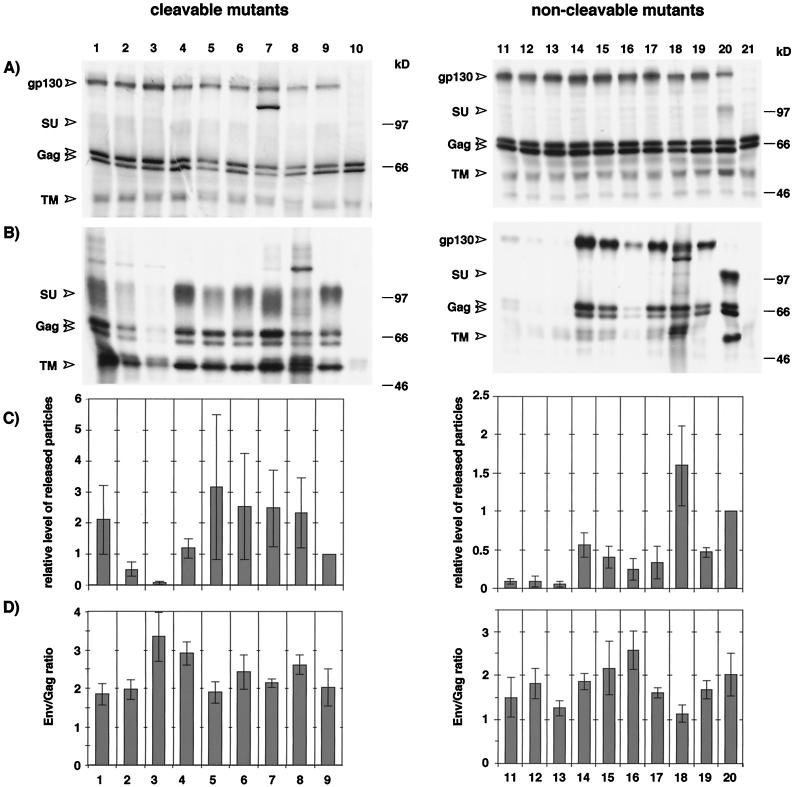

FIG. 2.

Expression analysis and support of FV particle release by MSD mutants. 293T cells were cotransfected with pMH62 and the Env expression constructs indicated below. (A) RIPA of metabolically labeled cell lysates performed with rabbit sera specific for the FV Env and Gag proteins. (B) Analysis of particle-associated FV proteins purified by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose cushion. (C) Particle release found with individual mutants relative to that with wild-type Env was standardized for cellular expression levels. The intensities of the cellular and supernatant Gag- and Env-specific bands were quantitated by densitometry. The mean values ± standard errors for the individual mutants are expressed relative to the EM02 construct, which was set at 1. The assays were performed two to five times per mutant. (D) Mean ratio of viral particle-associated Env to Gag proteins ± standard error as determined by quantitation of Env and Gag bands. The assays were performed two to five times per mutant. pMH62 was cotransfected with pczHFVenv EM21 (lane 1), pczHFVenv EM22 (lane 2), pczHFVenv EM23 (lane 3), pczHFVenv EM27 (lane 4), pczHFVenv EM28 (lane 5), pczHFVenv EM29 (lane 6), pczHFVenv EM30 (lane 7), pczHFVenv EM31 (lane 8), pczHFVenv EM02 (lane 9), pCDNA3.1+zeo (lane 10), pcHFVenv EM33 (lane 11), pcHFVenv EM34 (lane 12), pcHFVenv EM35 (lane 13), pcHFVenv EM36 (lane 14), pcHFVenv EM37 (lane 15), pcHFVenv EM38 (lane 16), pcHFVenv EM39 (lane 17), pcHFVenv EM40 (lane 18), pcHFVenv EM20 (lane 19), pcHFVenv EM02 (lane 20), or pCDNA3.1+zeo (lane 21).

However, the first experiments with some of these mutants revealed that altering the lysine residue dramatically increased the fusion activity of the FV Env protein (see below). In order to examine the influence of the individual MSD point mutations on FV particle release independently of cell lysis, occurring as a result of the excessive syncytium formation of Env-expressing cells, we combined them with the FV Env SU/TM cleavage mutant EM20 (Fig. 1B). This mutant itself was nonfusogenic (Fig. 3A) and yielded non-infectious particles (see Fig. 6) showing no morphologic abnormalities in electron microscopy analysis (data not shown). FV particle release by the EM20 mutant was reduced about twofold compared with wild-type FV Env (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 19 and 20, respectively). Analysis of FV particle release by the combination mutants revealed major differences among the individual mutants in supporting FV particle egress (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 11 to 21). In addition to the P960 mutants EM34 and EM35 (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 12 and 13), the K959 mutant EM33 (Fig. 2B and C, lane 11) showed a markedly reduced, mutants EM37, EM38, and EM39 (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 15 to 17) showed a marginally reduced, and EM36 (Fig. 2B and C, lane 14) showed similar particle release compared with the EM20 mutant itself (Fig. 2B and C, lane 19). The truncation mutant EM40 had significantly higher FV particle release activity than EM20 and slightly higher than the cleavable wild-type protein EM02 (Fig. 2B and C, lanes 18 to 20). The Env/Gag ratio of all mutants was within a twofold range compared with the EM20 cleavage mutant (Fig. 2D, lanes 11 to 20). Morphologic or structural abnormalities compared with wild-type particles could not be observed by electron microscopic analysis of several mutants (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

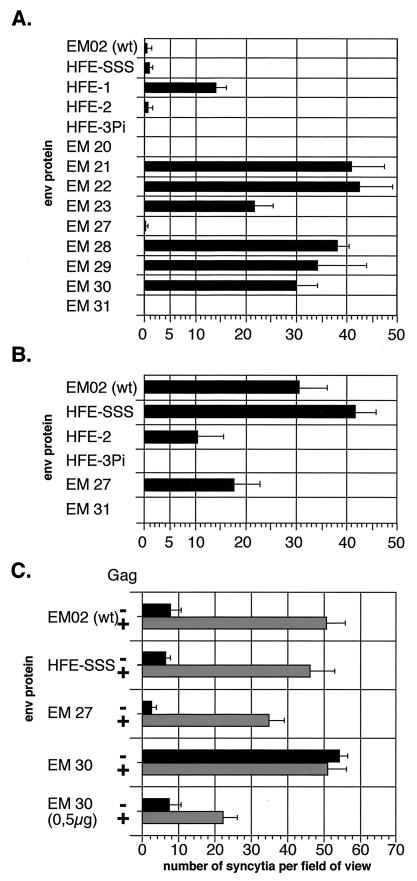

Fusion activity of FV Env mutants. If not indicated otherwise, 293T cells were transfected (A and B) with 15 μg of the individual Env expression constructs alone, or (C) 7.5 μg of Env expression plasmid and 7.5 μg of FV vector pMH62 expressing Gag-Pol (+) or an empty control vector (−) were cotransfected. The sensitivity of the assay could be increased by extending the cocultivation period from (A) 24 h to (B) 36 h with simultaneous sodium butyrate treatment. The average number of syncytia counted per field of view is given. The standard deviation for five fields counted per mutant is indicated. wt, wild type.

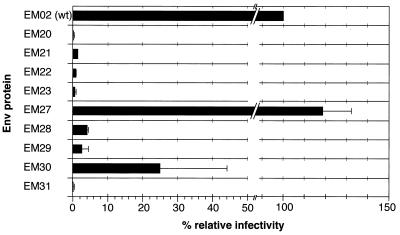

FIG. 6.

Relative infectivity of mutant viral particles normalized for virus-associated Gag proteins. 293T cells were transfected with the pDL01 FV vector constructs harboring the individual MSD mutants as indicated on the x axis. Transfer of the EGFP-Neo marker gene to HT1080 target cells was analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. The relative infectivities compared with particles containing the wild-type (wt) FV Env (EM02) normalized for the amount of viral particle-associated Gag proteins are given. The standard deviation of two independent experiments is shown. The detection limit of this assay is 0.5% of wild-type infectivity.

Taken together, these data indicate that the C-terminal part of the putative FV MSD is dispensable for FV particle egress. In addition, they imply a crucial role for the conserved P960 in this process and for K959 when analyzed in a nonfusogenic form.

K959 involved in control of FV Env fusion activity.

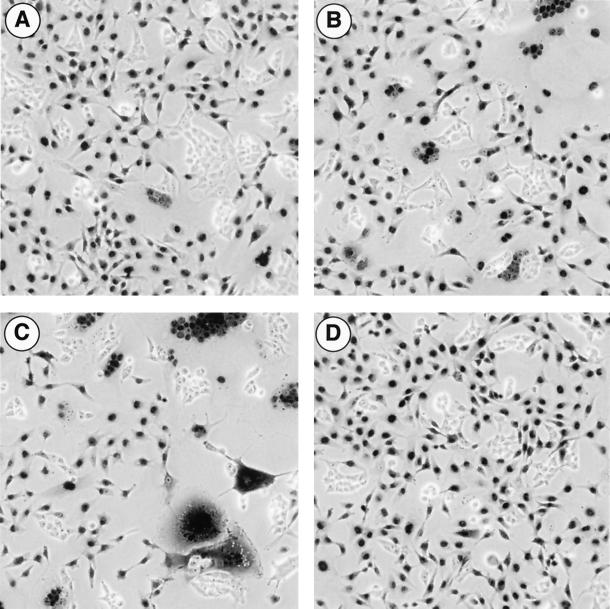

As mentioned above, the first experiments involving some of the point mutants showed a dramatic increase in syncytium formation in the transfected 293T cells. Therefore, we used a fusion assay to analyze the fusogenic capacity of the individual mutants in further detail. In this assay, 293T cells transfected with the envelope expression constructs were mixed 24 h posttransfection with HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells constitutively expressing a nuclear β-galactosidase protein. After an additional 24-h incubation period, lacZ expression was analyzed by a histochemical staining procedure, and syncytia were counted. In the analysis of fusion activity, we included some additional mutants described previously (Fig. 1B) (26). The different Env mutants examined could be divided into four major groups (Fig. 3A). The group of mutants that showed no syncytium formation at all consisted of the cleavage mutant EM20, the GPI-anchored HFE-3Pi, and the C-terminal truncation mutant EM31 (Fig. 3A and B). Another group comprising the wild-type FV Env protein (EM02), the conservative mutant EM27, the ER retrieval mutant HFE-SSS, and the HFE-2 mutant lacking the CyD had low but clearly detectable fusogenic activity (Fig. 3A and B). A third group included mutants with medium fusogenic activity, being 10- to 15-fold higher than found for the wild-type protein. Among those were the C-terminal truncation mutant HFE-1 and the K959P960 double mutant EM23 (Fig. 3A). Finally, the fourth group was made up of the EM28 and EM29 mutants with altered charge as well as the EM21, EM30, and EM22 mutants with hydrophobic amino acids in place of K959 or P960, respectively, having a 20- to 40-fold-higher fusogenic activity than the wild type (Fig. 3A). The sensitivity of the assay could be increased by longer cocultivation of the Env-expressing cells and the fusion partners, resulting in about 10-fold-higher values for the weakly fusogenic mutants (Fig. 3B). However, about 50 to 60 syncytia per view field was the maximum number that was reliably countable. Even after prolonged cultivation of cells transfected with nonfusogenic mutants, no syncytia could be observed (Fig. 3B). An example of the microscopic view of histochemically stained cell populations of one member of each group is shown in Fig. 4. These data demonstrate that the positively charged lysine residue at position 959 is involved in regulation of FV Env fusion activity, with the charge at this position playing an important role. Furthermore, they show that the full-length putative MSD of FV Env is required for retaining fusion activity, whereas the CyD is dispensable.

FIG. 4.

Sections of Env-expressing 293T cells cocultivated with NLS-lacZ-expressing HT1080 cells after histochemical β-galactosidase staining. 293T cells were transfected with individual Env expression constructs and subsequently cocultivated with HT1080 NLS-lacZ cells. The sections show fusion assays using (A) the wild-type Env protein (EM02), (B) the truncation mutant HFE-1, (C) the nonconservative mutant EM28 (K959E), and (D) mock-transfected cells (pCDNA3.1+zeo).

Efficient cell fusion by wild-type FV Env requires coexpression of capsids.

Syncytium formation is a hallmark of FV replication in cell culture. Thus, we were surprised to find only low fusogenic activity in our assay upon transfection of cells with the wild-type Env expression construct. We therefore examined the effect of Env-capsid interactions on Env fusogenic activity by cotransfecting 293T cells with some of the Env-encoding plasmids together with the pMH62 FV vector, expressing Gag-Pol, or with an empty vector backbone. As shown in Fig. 3C, a dramatic increase in fusion activity was observed for the low-fusogenic Env proteins (EM02, HFE-SSS, and EM27) when FV capsids were coexpressed. No significant increase was observed for those mutants (EM30) which were highly fusogenic in the preceding experiment. However, since 50 to 60 syncytia per field of view was the detection limit of the assay, we also analyzed a highly fusogenic mutant (EM30) under conditions of reduced amounts of Env protein. In this case, an increase in syncytium formation by coexpression of FV capsids was detected (Fig. 3C). We conclude from these experiments that the striking giant-cell formation upon FV replication in cell culture requires the expression of both Env and capsids and that the role of capsids could be overcome at least in part by mutating the conserved lysine in the Env MSD.

Analysis of Env cell surface expression.

To analyze whether the different fusogenic capacities of the mutated Env proteins depended on their degree of surface expression or altered biological features, we performed simultaneous surface biotinylation and metabolic labeling assays on transfected 293T cells (Fig. 5A and B). Relative cell surface expression of the individual mutants was then normalized for total protein expression (Fig. 5C). Again, we used the individual MSD point mutants in combination with the EM20 SU/TM cleavage site mutant to avoid access of Env proteins to biotinylation after the excessive syncytium formation induced by some of the MSD point mutants. Control transfection of cells with the pMH62 vector revealed the validity of the method, since the Gag and Pol proteins expressed by this vector were readily precipitated, while no biotinylation of these proteins could be detected (Fig. 5A and B, lanes 9 and 20, respectively). The analysis revealed that the mutant with the conservative K959R mutation displayed only a slightly higher cell surface expression (Fig. 5, lane 4), whereas all but one of the other point mutations affecting K959 or P960 (EM33 to EM36, EM37, and EM38) and causing increased fusogenicity gave two- to eightfold-elevated cell surface expression (Fig. 5, lanes 1 to 3, 5, and 6). The K959L mutation in EM39 gave cell surface expression slightly lower than that of wild-type FV Env (Fig. 5, lanes 7 and 8). To determine whether the unique phenotype of this mutant Env was a result of analysis in the uncleavable, nonfusogenic EM20 backbone, we examined cell surface expression of the single mutant (EM30) and compared it with that of the wild-type protein (EM02) as well as with the K959D (EM29) mutant with similar fusion activity. Only about fourfold more EM30 protein was biotinylated than wild-type protein, whereas there was a significant difference compared with the EM29 mutant, which had 15-fold more biotinylated protein than the wild type, supporting the unique phenotype of the K959L mutation in EM30 (Fig. 5A, lanes 11 to 13). Furthermore, analysis of the previously described C-terminal truncation and point mutants revealed that the nonfusogenic mutants HFE-3Pi and EM31 were expressed at four to fivefold-higher levels than wild-type FV Env (Fig. 5A, lanes 16, 18, and 19), whereas the weakly fusogenic mutant HFE-2 showed a fourfold-reduced expression level (Fig. 5A, lane 15). The other mutants, HFE-1 and HFE-SSS, had cell surface expression levels only slightly above that of wild-type FV Env (Fig. 5A, lanes 14, 17, and 19). Taken together, these results indicate that for most of the mutant proteins, fusogenic activity deviating from that of wild-type Env resulted from altered cell surface expression. However, the EM39 protein with the K959L mutation and one of the highest fusion activities observed when present as a single mutation (EM30) repeatedly showed cell surface expression levels slightly lower than that of wild-type FV Env. Therefore, this mutation seems to activate the fusion potential of the individual Env protein. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that the C-terminal half of the putative MSD is dispensable for stable membrane anchorage of the FV Env protein, although it is required for retaining fusogenic capacity.

FIG. 5.

Env cell surface expression on transfected 293T cells. 293T cells were transfected with individual expression constructs and metabolically labeled, and cell surface proteins were biotinylated. (A) Chemoluminescent signals of biotinylated FV Env proteins after incubation with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase and detection by ECL. (B) Autoradiogram of the radioimmunoprecipitated FV Env proteins using a chimpanzee serum recognizing all major FV proteins including Gag, Pol, and Env. (C) Mean relative cell surface expression ± standard error of individual FV Env mutants compared with the wild-type protein (EM02), standardized for total Env expression. The assay was performed two to three times per mutant. Radioactive signals and chemoluminescent signals were quantitated by densitometric analysis of the autoradiograms. The constructs tested were pcHFVenv EM33 (lane 1), pcHFVenv EM34 (lane 2), pcHFVenv EM35 (lane 3), pcHFVenv EM36 (lane 4), pcHFVenv EM37 (lane 5), pcHFVenv EM38 (lane 6), pcHFVenv EM39 (lane 7), pcHFVenv EM20 (lane 8), pMH62 (lane 9), pCDNA3.1+zeo (lane 10), pcHFVenv EM29 (lane 11), pcHFVenv EM30 (lane 12), pcHFVenv EM02 (lane 13), pcHFE-1 (lane 14), pcHFE-2 (lane 15), pcHFE-3Pi (lane 16), pcHFE-SSS (lane 17), pcHFVenv EM31 (lane 18), pcHFVenv EM02 (lane 19), pMH62 (lane 20), and pCDNA3.1+zeo (lane 21).

Infectivity of FV particles containing mutant Env proteins.

The infectivity of the released FV particles bearing mutated FV Env MSDs was analyzed by an EGFP marker gene transfer assay as described in Materials and Methods. 293T cells were transfected with the pDL01 constructs, and the cell-free virus titers were determined on HT1080 cells. The relative infectivity normalized for virus particle-associated Gag proteins of the FV particles pseudotyped with the individual mutants is shown in Fig. 6. The Env/Gag protein ratios of the individual mutant particles were within a twofold range of that of the wild-type control (data not shown). Supernatants containing particles harboring the conservative K959R (EM27) mutant were as infective as wild-type particles. The highly fusogenic K959L (EM30) mutant had fourfold-decreased infectivity. All other mutant particles showed 20- to 200-fold-decreased infectivities, several around the detection limit of the assay. Taken together, these data indicate that all but the conservative K959R and K959L mutations severely impair the ability of the FV Env protein to permit entry of viral particles into target cells.

DISCUSSION

As we reported previously, the putative FV MSD of the TM subunit plays an important role in FV particle egress (26). Using point mutations of two conserved residues within this domain, we observed a crucial role for P960 in this process. In the context of a nonfusogenic form of the FV Env protein having the SU/TM cleavage site inactivated, the negative effect of the P960 mutation was enhanced, and some K959 mutations also had a negative effect. Since the cleavage site mutant itself exhibited twofold-reduced particle release compared with the cleavable wild-type Env protein, it cannot be excluded that conformational changes introduced by the cleavage site mutation are the cause of the negative effect observed for some of the K959 mutations on FV particle release. For HIV-1 Env, for example, it has been observed that SU/TM cleavage mutants are inefficiently incorporated into HIV-1 particles (6). On the other hand, it is also possible that the supposedly normal particle release features of the nonconservative, highly fusogenic, cleavable K959 mutations are at least partially a result of the release of intracellular particles by massive syncytium formation, thereby masking the release defect observed in the noncleavable context.

The truncation mutation presented above, in the cleavable and noncleavable contexts, shows that only the N-terminal 15 amino acids of this domain are required for stable FV Env membrane anchorage and support of FV particle release. This is somewhat reminiscent of HIV-1 Env, for which the C-terminal regions of the unusually long putative MSD are similarly dispensable for stable cell surface expression (25). In the putative MSD of MuLV Env, as few as eight amino acids are sufficient to achieve membrane anchorage (27). Similarly, as observed for the FV MSD truncation mutant EM31, analogous HIV-1 and MuLV mutants were no longer fusogenic (25, 27), implying that the MSD is involved in membrane fusion, but this function is distinct from its role as a membrane anchor.

Upon expression of wild-type Env protein, we observed only weak fusogenic activity. Point mutations involving the conserved positively charged K959 and/or the adjacent P960 in the FV Env MSD resulted in an increase in fusogenicity. For all but one of the mutants, this increase is most probably mainly an effect of increased cell surface expression. This may indicate that K959 is part of a retention or retrieval signal negatively influencing the export of FV Env. In contrast, the conservative K959R mutant had fusion activity, cell surface expression, and FV particle release capacity comparable to those of the wild type, implying that the positive charge at this position is crucial for proper FV Env function. Interestingly, some of these point mutants showed significantly higher cell surface expression than a mutant in which the previously described ER retrieval signal in the CyD was inactivated (14), having a cell surface expression similar to that of wild-type FV Env. Goepfert et al. (14) reported enhanced precursor cleavage for this SSS mutant, indicating faster intracellular transport of this mutant protein. We found similar results previously (26) (Fig. 4), as judged from analysis of precursor cleavage and endonuclease H resistance of the SSS precursor compared with the wild-type protein. However, precursor cleavage is assumed to occur in the distal Golgi, i.e., intracellularly before the Env protein appears at the cell surface (8). Therefore, these results do not necessarily exclude our observation of similar cell surface expression for both proteins. Furthermore, we have recently identified additional domains in the FV Env protein which, when deleted or inactivated, result in dramatically increased intracellular transport and cell surface expression even in the presence of an intact ER retrieval signal in the CyD (unpublished observations). In our current view, the ER retrieval signal influences intracellular distribution of the FV Env protein but not cell surface expression. However, since we used a different cell line (293T) than Goepfert et al. (14) (COS-1) for analysis, a cellular effect for these differences cannot be excluded.

In the case of the HIV-1 Env, two arginine residues dispersed within the MSD are vital for fusogenic activity (18, 25). However, unlike the FV Env, changing the spacing or introducing a leucine residue instead of the positively charged MSD residues abolished HIV-1 Env fusogenic activity without affecting cell surface expression (18, 25). Changing the FV Env K959 to leucine resulted in drastic activation of the fusogenic activity of the individual Env proteins associated with cell surface expression at wild-type levels. This demonstrated that this residue of the FV MSD is directly involved in regulating FV fusion activity on the structural level and not only by influencing its intracellular transport.

The coexpression of FV capsids together with wild-type Env protein activated the fusion activity, as demonstrated by enhanced syncytium formation in the fusion assay. We therefore conclude that not only is FV Env required to export FV capsids, but also that FV capsid expression is essential to relieve the intracellular retention of Env protein. This retention could also be relieved by mutating the conserved lysine in the Env MSD. We suggest that structural changes in Env occur upon interaction with the capsid, which involves the MSD. This implies specific interactions between FV capsids and Env, which are currently under investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Ottmar Herchenröder for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the EU (BMH4-CT97-2010), Bayerische Forschungsstiftung, and DFG (Li621/2-1). D.L. was supported by the virology fellowship program of the BMBF, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin D N, Linial M L. The roles of Pol and Env in the assembly pathway of human foamy virus. J Virol. 1998;72:3658–3665. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3658-3665.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brody B A, Rhee S S, Hunter E. Postassembly cleavage of a retroviral glycoprotein cytoplasmic domain removes a necessary incorporation signal and activates fusion activity. J Virol. 1994;68:4620–4627. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4620-4627.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bullough P A, Hughson F M, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature. 1994;371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr C M, Chaudhry C, Kim P S. Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14306–14313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr C M, Kim P S. A spring-loaded mechanism for the conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin. Cell. 1993;73:823–832. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90260-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubay J W, Dubay S R, Shin H J, Hunter E. Analysis of the cleavage site of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein: requirement of precursor cleavage for glycoprotein incorporation. J Virol. 1995;69:4675–4682. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4675-4682.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du Bridge R B, Tang P, Hsia H C, Leong P M, Miller J H, Calos M P. Analysis of mutation in human cells by using an Epstein-Barr virus shuttle system. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:379–387. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Einfeld D. Maturation and assembly of retroviral glycoproteins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:133–176. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer N, Heinkelein M, Lindemann D, Enssle J, Baum C, Werder E, Zentgraf H, Muller J G, Rethwilm A. Foamy virus particle formation. J Virol. 1998;72:1610–1615. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1610-1615.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flügel R M, Rethwilm A, Maurer B, Darai G. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the env gene and its flanking regions of the human spumaretrovirus reveals two novel genes. EMBO J. 1987;6:2077–2084. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freed E O, Myers D J, Risser R. Mutational analysis of the cleavage sequence of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein precursor gp160. J Virol. 1989;63:4670–4675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4670-4675.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giron M L, de The H, Saib A. An evolutionarily conserved splice generates a secreted Env-Bet fusion protein during human foamy virus infection. J Virol. 1998;72:4906–4910. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4906-4910.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goepfert P, Shaw K, Wang G, Bansal A, Edwards B, Mulligan M. An endoplasmic reticulum retrieval signal partitions human foamy virus maturation to intracytoplasmic membranes. J Virol. 1999;73:7210–7217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7210-7217.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goepfert P A, Shaw K L, Ritter G D, Jr, Mulligan M J. A sorting motif localizes the foamy virus glycoprotein to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 1997;71:778–784. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.778-784.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goepfert P A, Wang G, Mulligan M J. Identification of an ER retrieval signal in a retroviral glycoprotein. Cell. 1995;82:543–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90026-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn H, Baunach G, Bräutigam S, Mergia A, Neumann-Haefelin D, Daniel M D, McClure M O, Rethwilm A. Reactivity of primate sera to foamy virus Gag and Bet proteins. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2635–2644. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-10-2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinkelein M, Schmidt M, Fischer N, Moebes A, Lindemann D, Enssle J, Rethwilm A. Characterization of a cis-acting sequence in the pol region required to transfer human foamy virus vectors. J Virol. 1998;72:6307–6314. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6307-6314.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helseth E, Olshevsky U, Gabuzda D, Ardman B, Haseltine W, Sodroski J. Changes in the transmembrane region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 envelope glycoprotein affect membrane fusion. J Virol. 1990;64:6314–6318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6314-6318.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higuchi R. Recombinant PCR. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, White T J, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughson F M. Enveloped viruses: a common mode of membrane fusion? Curr Biol. 1997;7:R565–R569. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindemann D, Bock M, Schweizer M, Rethwilm A. Efficient pseudotyping of murine leukemia virus particles with chimeric human foamy virus envelope proteins. J Virol. 1997;71:4815–4820. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4815-4820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindemann D, Rethwilm A. Characterization of a human foamy virus 170-kilodalton Env-Bet fusion protein generated by alternative splicing. J Virol. 1998;72:4088–4094. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4088-4094.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linial M L. Foamy viruses are unconventional retroviruses. J Virol. 1999;73:1747–1755. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1747-1755.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulligan M J, Yamshchikov G V, Ritter G D, Jr, Gao F, Jin M J, Nail C D, Spies C P, Hahn B H, Compans R W. Cytoplasmic domain truncation enhances fusion activity by the exterior glycoprotein complex of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 in selected cell types. J Virol. 1992;66:3971–3975. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3971-3975.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owens R J, Burke C, Rose J K. Mutations in the membrane-spanning domain of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein that affect fusion activity. J Virol. 1994;68:570–574. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.570-574.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pietschmann T, Heinkelein M, Heldmann M, Zentgraf H, Rethwilm A, Lindemann D. Foamy virus capsids require the cognate envelope protein for particle export. J Virol. 1999;73:2613–2621. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2613-2621.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ragheb J A, Anderson W F. Uncoupled expression of Moloney murine leukemia virus envelope polypeptides SU and TM: a functional analysis of the role of TM domains in viral entry. J Virol. 1994;68:3207–3219. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3207-3219.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rein A, Mirro J, Gordon Haynes J, Ernst S M, Nagashima K. Function of the cytoplasmic domain of a retroviral transmembrane protein: p15E-p2E cleavage activates the membrane fusion capability of the murine leukemia virus env protein. J Virol. 1994;68:1773–1781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1773-1781.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritter G D, Jr, Mulligan M J, Lydy S L, Compans R W. Cell fusion activity of the simian immunodeficiency virus envelope protein is modulated by the intracytoplasmic domain. Virology. 1993;197:255–264. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riviere I, Brose K, Mulligan R C. Effects of retroviral vector design on expression of human adenosine deaminase in murine bone marrow transplant recipients engrafted with genetically modified cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6733–6737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt M, Rethwilm A. Replicating foamy virus-based vectors directing high level expression of foreign genes. Virology. 1995;210:167–178. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang G, Baldwin D, Linial M, Mulligan M. Endogenous virus of BHK-21 cells complicates electron microscopy studies of foamy virus maturation. J Virol. 1999;73:8917. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8917-8917.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang G, Mulligan M J. Comparative sequence analysis and predictions for the envelope glycoproteins of foamy viruses. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:245–254. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Calder L J, Harrison S C, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Structural basis for membrane fusion by enveloped viruses. Mol Membr Biol. 1999;16:3–9. doi: 10.1080/096876899294706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]