Asylum seekers and refugees have been the subject of much media and political attention over recent months, but they are often misrepresented. In the first paper in this series we discuss the reasons that cause people to go into exile and the situation in which they find themselves as refugees in the United Kingdom. In subsequent papers we will examine the health needs of refugees, appropriate care and responses, the specific health effects of torture and organised violence, the needs of health workers, and the structural organisation of health services.

The term refugee is used to include people at all stages of the asylum process. The various definitions of refugee status are given in the box below.

Definitions of refugee status

Asylum seeker—asylum claim submitted, awaiting Home Office decision

Refugee status (accepted as a refugee under the Geneva Convention)—given leave to remain in the UK for four years, and can then apply for settled status (Indefinite leave to remain, see below). Eligible for family reunion for one spouse and all children under 18 years

Indefinite leave to remain (ILR)—given permanent residence in Britain indefinitely. Eligible for family reunion only if able to support family without recourse to public funding

Exceptional leave to remain (ELR)—the Home Office accepts there are strong reasons why the person should not return to the country of origin and grants the right to stay in Britain for four years. Expected to return if the home country situation improves. Ineligible for family reunion

Refusal—the person has a right of appeal, within strict time limits

Britain, as a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention, and for many years before this, has offered asylum to those fleeing from persecution and violence. Under the terms of the Convention, a refugee is defined as any person who, “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return it.”1

Summary points

The United Kingdom, as a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention, is committed to offer asylum to people fleeing from persecution

Most asylum seekers in Britain are from countries that are in conflict

Asylum seekers have had varied experiences which may include personal experience of violence as well as assaults on their social, economic, and cultural institutions

Many asylum seekers are highly skilled and previously had a high standard of living

Many are being dispersed throughout Britain to areas that have had little experience of working with refugees

Many are living below the poverty threshold, which poses a threat to their health

The United Kingdom is a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights, which forbids torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.2 This clause is also contained in the new Human Rights Act as an absolute right which cannot be restricted in any circumstances.3 The United Kingdom is also a signatory to the United Nations Convention against Torture, which forbids expulsion to a territory where people may be tortured.4 Amnesty currently estimates that torture takes place in 132 countries, approximately two thirds of all countries.5

Numbers involved

At present there are over 21 million refugees in the world.6 The majority of those seeking asylum in Britain come from countries that are in conflict, often fuelled by arms sold by richer countries.7 Over 90% of all casualties in modern warfare are civilians.8 The vast majority of refugees remain in countries neighbouring their own. Some, such as Palestinian refugees, have been displaced for generations. A further 25 million people are internally displaced within their own countries, separated from their homes and livelihoods but, although equally vulnerable, not granted the protection of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).6 It is estimated that nearly 1 in 100 of the entire global population is displaced by war.9

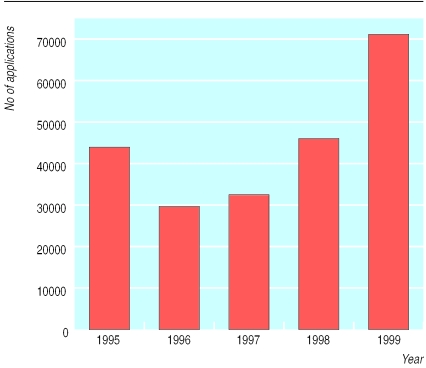

The number of people seeking asylum in the United Kingdom has fluctuated over recent years (figure). The United Kingdom ranks ninth in Europe in terms of asylum applications per head of population.11

Most asylum seekers in Britain are single men, under the age of 40, although worldwide most refugees are women. Many families in Britain are without one parent, who may be missing or dead, and there is an appreciable number of unaccompanied minors. Numbers from each country fluctuate principally according to the local human rights situation. For example, much of the increases in 1998 and 1999 were from the former Republic of Yugoslavia.

Previous experiences

The experiences which people may have endured include massacres and threats of massacres, detention, beatings and torture, rape and sexual assault, and witnessing death squads and torture of others; being held under siege, destruction of homes and property and forcible eviction, disappearances of family members or friends; being held as hostages or human shields; and landmine injuries. Adults and even children may have been conscripted into the army, and women and girls may have been forced to become sexual slaves. Other forms of persecution are persistent and long term: political repression, deprivation of human rights, and harassment. In camps refugees may have experienced prolonged squalor, malnutrition, lack of personal protection, and deprivation of education; children may have been deprived of the opportunity to play normally. These personal experiences are likely to have been accompanied by damage, frequently intentional, to social, economic and cultural institutions.12,13

The myth of “bogus” refugees

It is simplistic and erroneous to consider that all asylum seekers who do not fulfil the terms of the Geneva Convention (see box) are economic migrants or “bogus” refugees. Large numbers of people are caught up arbitrarily in civil wars and accused by each side of supporting the other. Some are detained and tortured because of their political beliefs. Others are detained and ill treated following activities such as free association or investigative journalism which, although protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,14 are criminalised in some countries. People may be tortured by criminal gangs for the purpose of extortion and the security forces fail to protect them through intimidation, corruption, or because they themselves are the assailants.13 In many countries minority ethnic groups suffer harassment and assault. The Roma are persecuted in this way throughout Europe, and in some countries there seems to be a situation close to ethnic cleansing in which all those not perceived as being nationals are intimidated into leaving.15 People may also be forced into leaving for environmental reasons, such as major climate changes and natural disasters (for example, recent floods in Mozambique, India, and Bangladesh; Hurricane Mitch in Central America; drought in the Horn of Africa; and the volcanic eruption in Montserrat); or from displacement by major civil engineering projects or expansionist landowners. It is therefore understandable that they should try to seek a better and more peaceful life elsewhere.

The term economic migrant has become one of abuse although the United Kingdom, notably, has often encouraged and depended on economic migrants to develop many services and industries, including the NHS, and continues to do so.16 In this era of global capitalisation, it is no surprise that people follow the free movement of capital in search of work. Inequalities between rich and poor, both between and within countries, continue to widen.17 Pressure by the NGO Coalition Jubilee 2000 on the G8 countries (the eight most industrialised nations in the world) to cancel unpayable debts owed to them by the world's poorest countries, under a fair and transparent process,18 has not yet achieved success. The question has been asked, “What is the point of immunising children if we are then going to starve them?”19 To be granted refugee status, however, an asylum seeker must meet certain specific criteria under the terms of the Geneva Convention (see above), and must show that he or she is personally at risk, which may be difficult to prove. The asylum process is lengthy, complicated, and intrinsically stressful, with the continual fear for the asylum seeker, until the process is complete, of being sent back to the original country.20

Some asylum seekers and refugees have been detained and tortured in their own countries, and exposure of others to violence is widespread. Whatever the person's previous experience, it is the likelihood of persecution on return that is crucial for success of the asylum application. Some may be considered ineligible if their country has experienced a political change since they fled, though a change in government does not necessarily mean cessation of violence, as the situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly Zaire, shows.21

Barriers to escape

Currently it is virtually impossible to be a “legal” asylum seeker in the United Kingdom, since visa requirements necessitate the acquisition of false documents. The policy of fining airlines and transport companies found to be carrying people without the correct documents means that it is becoming increasingly difficult for refugees to travel and forces them to depend on human traffickers. The purpose of this legislation has been to deter economic migrants, but we do not know how many people genuinely fleeing from persecution it has prevented from reaching a place of safety. A sense of déjà vu may be felt in remembering the 1938 Evian Conference, during which European States, the United States, and Australia, which were all aware of rising fascism in Germany and the plight of Jewish refugees after the German Anschluss, placed limits on the number of Jewish refugees whom they were prepared to accept. They cited lack of space and economic depression and failed to organise any evacuation programmes for Europe's threatened Jews.22

Skills of refugees

The belief that most asylum seekers come to Britain for welfare benefits is at odds with the fact that many are highly skilled and previously enjoyed a high standard of living. Sixteen of a sample of 40 asylum seekers (40%) in Australia had worked in professional or management roles in their countries of origin,20 and similar figures have been found in Britain.23 Many pay the equivalent of several thousand pounds to a trafficker to reach a place of potential asylum. The skills of health professionals, teachers, and other workers could benefit Britain, but it is difficult for their experience and qualifications to be recognised.24 Yet while it costs an estimated £200 000 to train a new doctor, refugee doctors can be accredited to practise in Britain at an average cost of £3500.25

Planning and needs assessment

The lack of accurate demographic data on either the existing refugee population or new arrivals25 makes the assessment of needs and planning of local services difficult and there is an urgent need to develop comprehensive and accurate information. The number of refugees and asylum seekers who have arrived in the past 15 years and who are living in London is estimated to be between 240 000 and 280 000, but different sources of information yield different figures.26 There are not yet figures for the rest of the United Kingdom.

Dispersal

Under the 1999 Immigration and Asylum Act many asylum seekers are being dispersed throughout Britain to areas that have previously had little experience of working with refugees. New applicants are provided with vouchers and a small amount of cash that gives them an income only 70% of that of normal income support. Currently children under 16 receive £26.60 per week, adults £36.54, and a couple £57.37. Those who leave their allocated accommodation for any reason, including racist abuse or to be nearer to their family or community, lose their entitlement to support. In spite of this, it is likely that many asylum seekers will leave the outlying areas to which they have been sent to come to London, where there are established support networks, thereby being removed from the asylum support system and adding to the number of destitute people in the capital.

Access to health care

Asylum seekers and refugees, unlike other overseas visitors, are entitled to all NHS services without payment, yet many say they have difficulty obtaining health care.27,28 Many, in particular young single homeless people,29 have found it impossible to register with general practitioners at all, while others may be only temporarily registered and not entitled to a health check, screening, or immunisation, and previous notes will not be available. Mobility may be cited as a reason to register only temporarily, but 70% of responders to a study on refugees in 1995 had not moved in the previous year, although this figure may now be affected by dispersal.30

Difficulties that face health workers include language, pressure of time, lack of understanding of cultural differences, and lack of expertise. Refugees are perceived as having huge needs that are difficult to fulfil and as being very demanding. This may be true for some individuals—as it is in the general population—but many refugees are actually reluctant to make demands. The health of asylum seekers is affected by many aspects of their experiences, both past and present, including multiple loss and bereavement, loss of identity and status, experience of violence and torture, poverty and poor housing, and racism and discrimination,31 and the responses needed are not solely medical. The effects of poverty on both physical and mental health have been well documented and it is of deep concern that asylum seekers are being forced to live below the poverty threshold.32 If not otherwise exempt, those on low income can apply with an HC1 form for an AG2 exemption certificate in order to receive free prescriptions, dental treatment, optician services, and hospital travel costs. The form, however, is 16 pages long and available only in English, and the certificate itself is valid for only six months. (Forms are available from the Health Benefits Division, Sandyford House, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 1DB; tel 0191 213 5000.)

Some refugees may acquire a collection of drugs, many of them inappropriate, because health workers have been unable to take an adequate history. Some have experiences of abuse which they have previously never described, and the process of giving testimony in itself can be therapeutic.33 For a health worker to listen is very valuable, but it is not easy for overstretched health workers to spare the necessary time, and in many areas access to interpreters is limited.

Figure.

UK asylum seekers 1995-9 (Home Office data10)

Figure.

Wellwishers in Leeds welcome refugees arriving in 1999

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank our clients and our colleagues, too numerous to mention individually, who have inspired our thinking and have provided valuable comments on our work.

This is the first in a series of three articles

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.United Nations. Convention relating to the status of refugees of 28 July 1951. Geneva: United Nations; 1951. www.unhcr.ch/refworld/refworld/legal/instrume/asylum/1951eng.htm (accessed 20 Jan 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Council of Europe. European convention on human rights, 1950. (Article 3.) www.hri.org/docs/ECHR50.html (accessed 20 Jan 2001).

- 3.Human Rights Act 1998. London: HMSO; 2000. www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980042.htm . (Article 3.) www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980042.htm (accessed 20 Jan 2001). (accessed 20 Jan 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations. Human rights: a compilation of international instruments. Geneva: United Nations; 1988. Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 1984.www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/h_cat39.htm (accessed 20 Jan 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amnesty International. Annual report 2000. London: Amnesty International; 2000. www.web.amnesty.org/web/ar2000web.nsf/ar2000 (accessed 20 Jan 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Refugees and others of concern to UNHCR. Statistical overview. Geneva: UNHCR; 1999. www.unhcr.ch/statist/99oview/toc.htm (accessed 20 Jan 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sivard R. World military and social expenditures. Washington, DC: World Priorities; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Children in situations of armed conflict. New York: UNICEF; 1986. . (E/ICEF.CRF.2.) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Summerfield D. The psychological legacy of war and atrocity: the question of long-term and transgenerational effects and the need for a broad view. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:375–377. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199606000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Home Office. Statistical Bulletin. London: Research and Statistics Directorate; 1995-9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Council of Europe. Recent demographic trends. Strasbourg: Council of Europe; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnett A. Guidelines for healthworkers providing care for Kosovan refugees. London: Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture, Department of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Summerfield D. The impact of war and atrocity on civilian populations: basic principles of NGO interventions and a critique of psycho-social trauma projects. London: Relief and Rehabilitation Network Overseas Development Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Nations. Universal Declaration on Human Rights. Geneva: United Nations; 1948. www.un.org/Overview/rights.html (accessed 20 Jan 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peel M. Asylum seekers in the UK from Council of Europe members. London: Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milne S. Foreign Legion. Guardian 2000 Sep 1.

- 17.United Nations Development Programme. Human development report. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jubilee Coalition 2000. Breaking the chains. London: Jubilee 2000; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godlee F. Third World debt. BMJ. 1993;307:1369–1370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6916.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinnerbrink I, Silove D, Field A, Steel Z, Manicavasagar V. Compounding of pre-migration trauma and post-migration stress in asylum seekers. J Psychol. 1997;131:463–470. doi: 10.1080/00223989709603533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porta C. Zaire, a torture state. London: Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon Wiesenthal Centre. http://motlc.wiesenthal.com (accessed 20 Jan 2001).

- 23.Peel M, Salinsky M. Caught in the middle: survivors of recent torture in Sri Lanka. London: Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pile H. The asylum trap: the labour market experiences of refugees with professional qualifications. London: Low Pay Unit; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Audit Commission. Another country. Implementing dispersal under the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999. Abingdon: Audit Commission Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldous J, Bardsley M, Daniell R, Gair R, Jacobson B, Lowdell C, et al. Refugee health in London—key issues for public health. London: East London and the City Health Authority; 1999. . (Health of Londoners project.) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones D, Gill PS. Refugees and primary care: tackling the inequalities. BMJ. 1998;317:1444–1446. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7170.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fassil Y. Looking after the health of refugees. BMJ. 2000;321:59. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7252.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Small C, Hinton T. Reaching out: a study of black and minority ethnic single homeless people and access to primary health care. London: Health Action for Homeless People and Lambeth Health Care NHS Trust; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carey-Wood J, Duke K, Karn V, Marshall T. The settlement of refugees in Britain. London: HMSO; 1995. . (Home Office research study 141.) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levenson R, Coker N. The health of refugees. London: King's Fund; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Connelly J, Schweiger M. The health risks of the UK's new Asylum Act. BMJ. 2000;321:5–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7252.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cienfuegos AJ, Monelli C. The testimony of political repression as a therapeutic instrument. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1983;53:43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1983.tb03348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]