Abstract

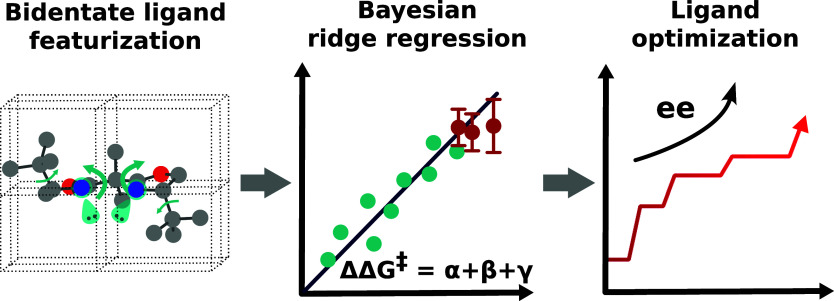

Chiral ligands are important components in asymmetric homogeneous catalysis, but their synthesis and screening can be both time-consuming and resource-intensive. Data-driven approaches, in contrast to screening procedures based on intuition, have the potential to reduce the time and resources needed for reaction optimization by more rapidly identifying an ideal catalyst. These approaches, however, are often nontransferable and cannot be applied across different reactions. To overcome this drawback, we introduce a general featurization strategy for bidentate ligands that is coupled with an automated feature selection pipeline and Bayesian ridge regression to perform multivariate linear regression modeling. This approach, which is applicable to any reaction, incorporates electronic, steric, and topological features (rigidity/flexibility, branching, geometry, and constitution) and is well-suited for early stage ligand optimization. Using only small data sets, our workflow capably predicts the enantioselectivity of four metal-catalyzed asymmetric reactions. Uncertainty estimates provided by Bayesian ridge regression permit the use of Bayesian optimization to efficiently explore pools of prospective ligands. Finally, we constructed the BDL-Cu-2023 data set, composed of 312 bidentate ligands extracted from the Cambridge Structural Database, and screened it with this procedure to identify ligand candidates for a challenging asymmetric oxy-alkynylation reaction.

Keywords: homogeneous catalysis, bidentate ligands, asymmetric catalysis, Bayesian optimization, machine learning

1. Introduction

Statistical methods accelerate the discovery and optimization of chemical reactions in homogeneous catalysis.1−18 Employing these “data-driven” approaches requires abundant, high-quality data19−21 that are often scarce. Ligand optimization, in particular, suffers from this problem since most experimental data sets tend to be size-limited as a result of ligand screening campaigns that often consist of fewer than a dozen experiments. In such “low data” regimes, nonlinear statistical models perform poorly due to overfitting. On the other hand, multivariate linear regression (MLR) models offer data-efficient and intuitive alternatives that can be developed from only a few samples yet are robust, interpretative (i.e., the way they work is exposed and understandable), and often extrapolative to unseen ligands.

To develop MLR models, catalysts are usually first optimized using density functional theory (DFT) and then featurized.13,16,17,22−31 The resulting molecular features (e.g., atomic charges, local stretching frequencies, and cone/bite angles) are low-dimensional and highly interpretable,17,32−34 which allows design principles and hypothesized reaction pathways to be derived from the fitted models.18,22,23,26,28−31,35 This established approach, however, suffers from two significant drawbacks: first, specific features for the chemical problem of interest must be selected for the MLR model and second, only the most relevant of these features are used in developing the final model. As a result, MLRs are often not transferable to different settings (e.g., a similar reaction incorporating a different family of ligands) as those features previously selected may not be defined. To avoid this issue, molecular grids where similar structures are superimposed have been used.2,22−24,36−40 Alternatively, Gensch et al.41 recently introduced a comprehensive featurization strategy for monodentate organophosphorus ligands that facilitates the creation of MLRs for any possible reaction class. Establishing this paradigm for more complex ligand types is of great interest for developing transferable predictive models across catalyst families and reaction classes.17

To this end, here we present a reaction-agnostic workflow applied to bidentate ligands that employs, among others, rarely used topological-based features.3,42−44 Coupling this featurization strategy with an automated feature selection pipeline using Bayesian ridge regression (BRR)45 allows development of models that capably predict the enantioselectivity of four different reaction classes while highlighting the importance of using topological-based features. Moreover, by leveraging the calibrated uncertainty estimations from BRR, we demonstrate Bayesian optimization (BO) for optimal ligand screening46−53 on the BDL-Cu-2023 data set, an original pool of 312 chiral bidentate ligands extracted from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD). Previous work using BO for catalyst optimization used either Gaussian process regression (GPR) or ensembles of models.54,55 Overall, this work demonstrates that linear models are more accurate and data-efficient than nonlinear methods in the “extremely low” data regime.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sets

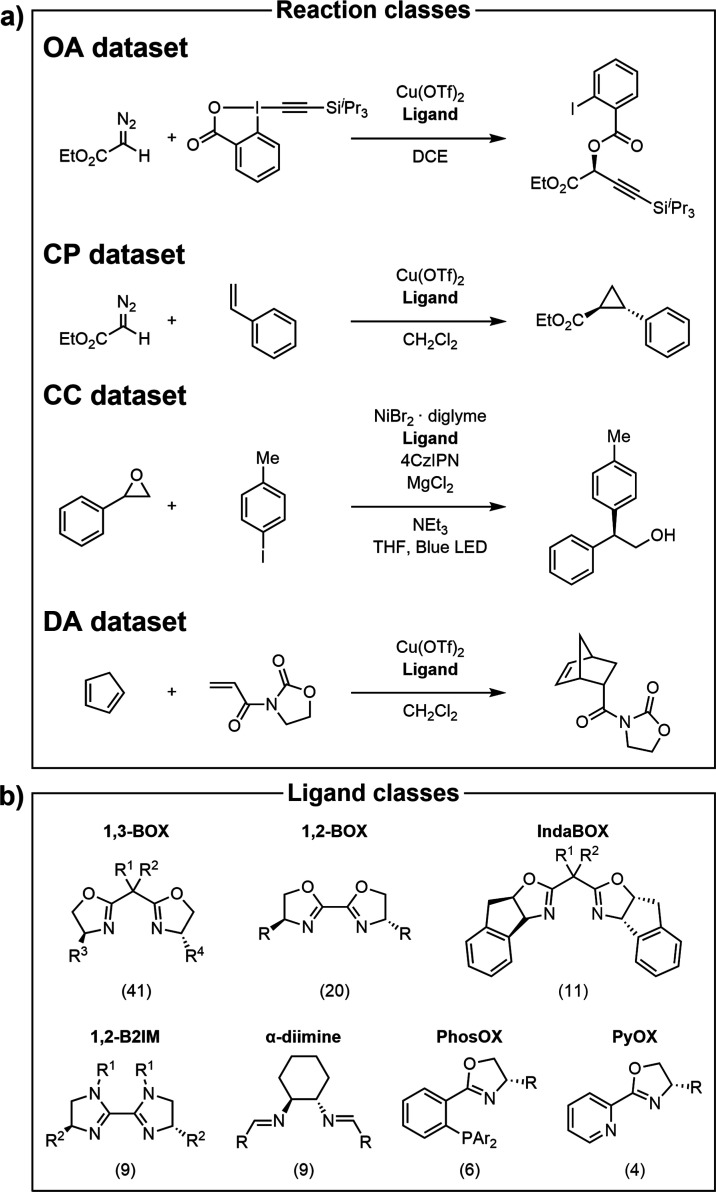

To develop, train, and test our pipeline, four asymmetric reaction classes that previously underwent extensive experimental ligand screening were selected for examination (Scheme 1, top): copper-catalyzed oxy-alkynylation of diazo compounds with hypervalent iodine reagents (OA),56 copper-catalyzed cyclopropanation of styrene with diazo esters (CP),57 nickel/photoredox-catalyzed cross-electrophile coupling of styrene oxides with aryl iodides (CC),26 and a copper-catalyzed Diels–Alder ligand benchmark reaction with cyclopentadiene and an imide (DA).58−64Table 1 gives an overview of these data sets. For each reaction, the reactants, reagents (except the ligand), and solvent were kept constant, while reaction conditions (metal loading, time, temperature, etc.) varied among experiments. For this reason, the data sets are small (ranging from 19 to 30 data points) as they include only ligand screening experiments (see Supporting Information Section S2 for details). Our approach currently does not account for substrate effects, rather we choose to focus on catalyst optimization (see Supporting Information Section S5.1 for discussion). For three of the four curated data sets, all ligands originated from a single publication, while the fourth data set (DA) contains ligands taken from seven different publications, which introduces additional noise in the data resulting from different experimental setups. For the OA data set, additional ligands with enantiomeric excesses not part of the original publication56 were included from electronic laboratory notebook entries (see Supporting Information Section S2.1).

Scheme 1. (a) Candidate Asymmetric Reactions Used to Develop and Test the Presented Pipeline; (b) Ligand Families Used in These Reaction Classes.

The number of unique ligands per class is shown in parentheses.

Table 1. Overview of the Data Sets Used in This Work.

| data set | OA | CP | CC | DA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of data points | 19 | 30 | 29 | 30 |

| # of publications | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| oxazoline ligands | 16 | 30 | 20 | 21 |

Combining all four data sets gives a total of 100 unique bidentate ligands, which were curated as a ligand pool for exploration (see Section 3.2). Most reactions (across all data sets) used bis-oxazoline (BOX)-type ligands (see Table 1), but other ligand classes [bi-2-imidazolines (B2IM), α-diimines, phosphorus-oxazolines (PhosOX), and pyridine-oxazolines (PyOX, Scheme 1, bottom)] are also present in smaller numbers. In addition, bidentate ligands bound to Cu(I) or Cu(II) found in the CSD65,66 were extracted with cell2mol .67 This yielded 312 new ligands possessing at least one chiral atom, the most common being N,N- and O,N-ligands (P,N-, P,O-, P,P-, S,N-, S,O-, and S,S-ligands are also present although in smaller numbers, see Supporting Information Section S2.2). This separate pool, which we call the BDL-Cu-2023 data set, was used to conduct further exploration (vide infra).

2.2. Bidentate Ligand Featurization

Molecular features (i.e., molecular descriptors) were split into three categories: electronic, steric, and topological (Figure 1a) and further categorized based on their intensive or extensive nature. To maximize generality, the only local features used describe the ligand’s two complexing atoms (that bind the metal), which are present in all bidentate ligands. Steric features were computed using a consistent alignment for all ligands that allows the ligand’s molecular volume to be reproducibly split into octants, quadrants, and halves (see Supporting Information Section S4.1). Full and buried volumes were computed following the recommendations of Cavallo et al.68

Figure 1.

Featurization of bidentate ligands. (a) Alignment of the bidentate ligands in space and feature classes. (b) PCA map of the feature space for all ligands with all available features.

Topological features, seldom exploited in multilinear regression models for homogeneous catalysis, were determined from vertex and edge information on the ligand’s molecular graph that were generated using covalent radii to assign bonds based on the DFT-optimized geometry. This category includes global topological features (e.g., Wiener, Hosoya Z, and Balaban J indices),69−71 bond-fragment-based descriptors (e.g., the indices introduced by Kier and Hall),72−79 and bond-order quantities (e.g., local and global simple indices and the CREST flexibility index).80,81 Variants of existing topological descriptors, originally used for drug design, were also developed and included to capture catalyst rigidity/flexibility.

Summed together, this strategy yields a total of 232 features for each ligand, which constitutes a representation of bidentate ligand space. The principal component analysis (PCA) plot of the featurized ligands in Figure 1b showcases how these features assemble ligands belonging to the same family (see Scheme 1b) while keeping related ligand families adjacent, in agreement with chemical intuition. Note that, by design, all features can be obtained for any possible bidentate ligand using the Moltop package and associated scripts available at https://github.com/lcmd-epfl/rafbl. Further details and a complete description of all 232 features are given in the Supporting Information (Section S4).

2.3. Regression and Optimization Methods

In this work, BRR (a regularized variation of least-squares fitting) was used to fit the MLR models whose parameters were estimated using Bayesian inference, which provides a calibrated uncertainty for each prediction. To avoid overfitting, model complexity was limited to a maximum of three features per model using a forward-step feature selection technique (see Supporting Information Section S5.2 for details).82 We find that this approach leads to highly interpretable, robust models that outperform nonlinear models (see Supporting Information Section S5.5 for a detailed comparison).

To guide ligand screening, a pool-based BO, in which prospective ligands are run through the BRR-fitted model, was employed. For each ligand x in the pool, the expected improvement (EI)83 defined as

| 1 |

| 2 |

was computed. Here, μ represents the predicted value, μ+ the current best value, σ the standard deviation, Φ the cumulative distribution function, and ϕ the probability density function. New results are subsequently incorporated into the training set, and the process is repeated until unexplored ligands each have EI scores lower than those already seen by the model. This implies that no further improvement (i.e., no better ligand) is expected within the pool.

2.4. General Workflow

Figure 2 provides an overview of our proposed workflow. In step 1, CuCl2L structures are optimized at the PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP level (see Computational Details), followed by automatic feature extraction for each structure (Step 2). The Eyring equation is then used to convert enantiomeric excesses (for experimentally available data) to energies (ΔΔG⧧) with the corresponding reaction temperature. Using the forward step technique in combination with BRR, the most promising feature combinations are selected (Step 3, see Section 2.3). The initial model selection is then evaluated with leave-one-out cross validation (LOO), and the most promising model is chosen using the adjusted R2 of the left-out samples (adj. R2LOO, Step 4, see Supporting Information Section S5.2). With the final model, a pool of ligands is screened, and BO is used to identify the most promising candidates, which should next be tested (Step 5).

Figure 2.

General workflow for model selection. (1) Ligands are optimized with a metal center to obtain the desired geometry. (2) 232 features are extracted from the metal-free structure. (3) The most promising feature combinations are identified through testing. (4) The best features undergo cross-validation, and the best BRR model is obtained. (5) This resulting model is used for ligand screening with BO.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Generation of MLR Models

Using the above pipeline, an interpretable MLR model was generated for each of the four Scheme 1 data sets (Figure 3). Recall that no human input was required for featurization, feature selection, and generation of the final models (i.e., all reactions used the same initial features and were run through the pipeline in an automated fashion). In general, the models perform well, with MAELOO not being higher than 0.29 kcal/mol. As in standard MLR, examining the normalized weights of these models reveals insight into the key aspects of the ligand that lead to high enantioselectivity (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Fitted models for the four data sets, where N is the number of points, adj. R2 is the adjusted coefficient of determination, MAE is the mean absolute error, and the LOO subscript indicates the scores for the leave-one-out cross-validation. The model equation is represented in each plot with a depiction of the normalized weights. Electronic features are represented in teal, steric in orange, and topological in red. (a, OA data set) Lone-pair NBO energies of the smaller half, normalized hydrogen-free volume of the smaller half (−x), and normalized original Kier 2καl index. (b, CP data set) Volume of octant 8 (x, y, −z), buried volume of the northwest quadrant Q2 (−x, y), and normalized 2χ. (c, CC data set) Absolute difference of lone-pair NBO energies, normalized buried volume of the southwest quadrant Q3 (−x, −y), and normalized 1χ index. (d, DA data set) Absolute difference of lone-pair NBO energies, buried volume of octant 5 (x, −y, −z), and normalized 3χv index. See Supporting Information Section S4 for a complete description of all features.

For the oxy-alkynylation of diazo compounds model (OA, Figure 3a), the selected features are the lone-pair natural bond orbital (NBO) energies of the smaller ligand half (−x, electronic), the normalized hydrogen-free volume of the smaller half (−x, steric), and the normalized original Kier 2καl index (lower values—more rigid, topological). The large topological feature weight indicates that a rigid catalyst structure is the most crucial element in determining enantioselectivity with sterics and electronics relegated to smaller roles. Taken together, these design principles indicate that indane-derived BOX (IndaBOX) ligands are well suited for this reaction as they are simultaneously both bulky and rigid. We hypothesize that catalyst rigidity contributes to a greater difference between the energies of the transition states leading to both enantiomers of the product.

For the cyclopropanation of styrene with diazo esters model (CP, Figure 3b), no electronic feature but rather two steric features were selected:

an octant (x, y, −z, steric), the normalized northwest quadrant (−x, y, steric), and the normalized Hall 2χ index (higher values—more rigid, topological).

Combined, sterics play a more important role than rigidity, in agreement

with previously proposed models.57 A closer

examination of the model reveals that the −x, y quadrant  is especially important for enantioselectivity.

Nevertheless, the Hall index possesses the highest weight overall,

and its importance should thus not be ignored.

is especially important for enantioselectivity.

Nevertheless, the Hall index possesses the highest weight overall,

and its importance should thus not be ignored.

For the cross-electrophile

coupling of styrene oxides with aryl

iodides model (CC, Figure 3c), the selected features are the difference of lone-pair

NBO energies (electronic), the normalized southwest quadrant (−x, −y, steric), and the normalized 1χ Hall index (higher values—more bonded, topological).

Here, the most important feature is steric  and indicates that the southwest quadrant

should be kept free, which aligns with previous postulations regarding

the origin of stereoselectivity.26 Overall,

the family of B2IM ligands with closed, more branched backbones matches

well with the features of the model. Note that the adjusted R2 of 0.75 of our model is similar to the adjusted R2 of 0.74 previously reported for CC,26 which shows that our pipeline yields

similar predictivity and analogous interpretation without requiring

information about reaction intermediates.

and indicates that the southwest quadrant

should be kept free, which aligns with previous postulations regarding

the origin of stereoselectivity.26 Overall,

the family of B2IM ligands with closed, more branched backbones matches

well with the features of the model. Note that the adjusted R2 of 0.75 of our model is similar to the adjusted R2 of 0.74 previously reported for CC,26 which shows that our pipeline yields

similar predictivity and analogous interpretation without requiring

information about reaction intermediates.

Finally, for the Diels–Alder reaction of cyclopentadiene in an imide model (DA, Figure 3d), the selected features are the NBO energies (electronic), a buried hydrogen-free octant (x, −y, −z, steric), and the normalized 3χv Hall index (higher values—more rigid, topological). Here, as in the OA data set, the topological feature is found to be dominant. Being built from seven different publications, this reaction is particularly challenging, and the reported adjusted R2 is rather poor. Nevertheless, our model has cross-validated errors of less than 0.3 kcal/mol.

The MLR models obtained from our pipeline for each of the four reaction data sets discussed above are both simple and interpretable owing to their limited number of features and selected composition. The importance of topological features that describe catalyst rigidity/flexibility (which, recall, are typically absent in multilinear regression models for homogeneous catalysis) across all four reactions is noteworthy as in three out of four cases these factors play the most important role (as seen through examination of the normalized weights).

3.2. Pool-Based Ligand Optimization with BRR and BO

As illustrated above, the fitted BRR models can be used to elucidate design principles by analyzing the selected features/weights and interpreting the trends. Additionally, they may also be directly employed for ligand optimization (e.g., to predict ligands that will impart higher selectivity). In this context, the ability to accurately predict higher ΔΔG⧧ values than those present in the data set in unseen samples is crucial, particularly for cases where the training set contains only ligands with low enantioselectivities (e.g., an initial batch based on similar reactions). To simulate this situation, we performed an 80/20 train/test split on the OA data set to test the model on out-of-range predictions (see Supporting Information Section S5.4 for more tests). As shown in Figure 4a, the test set includes the four best experimental ligands (red points), while the training set contains ligands with similar or worse performance (teal points). The complete pipeline was then rerun using the reduced training data (teal points alone), which produced a similar (but not identical) model to that shown in Figure 3. Overall, this refit model shows low errors (MAE of 0.19 kcal/mol) for unseen samples and well-calibrated uncertainties that are nearly within 1σ from the reported experimental values except for one outlier (BOX ligand with an additional oxazoline arm). Comparing this model with the full model (Figure 3a), it is easy to spot that this inaccuracy is caused by the steric feature. The enhanced uncertainty estimation, powered by BRR, coupled with the low prediction error on the test set, demonstrates that our pipeline yields models capable of accurately predicting the selectivity of unknown ligands, including those anticipated to have greater selectivity than that of the training set.

Figure 4.

Retrospective and prospective experiments for the OA data set. (a) 80/20 train (teal)/test (red) split. Error bars correspond to 1σ. The selected features are lone-pair NBO energies of the smaller half, buried volume of the southeast quadrant Q4 (x, −y), and the normalized original 2καl. (b) Retrospective BO analysis. The “Report” line follows the original optimization timeline. New batches of ligands are represented as black crosses. Bar plots represent the ΔΔG⧧ values of each ligand in the batches. The BO starts with the three points from the first batch.

Ideally, the newly developed BRR model can be used to more rapidly identify an ideal catalyst, which would avoid performing experiments that yield no improvement past the optimum. To assess this, we used the dates reported in the original electronic laboratory notebook to construct a timeline depicting the experimental reporting of each ligand (teal, Figure 4b). Here, the best-performing ligand was found between the sixth and eighth experiments; all subsequent attempts did not yield any further improvement. Having established the model’s ability to reliably predict out-of-range ligands with calibrated uncertainties (vide supra), we conducted BO to efficiently find the optimal ligand from a pool of candidates using the same initial three ligands as the training set. As shown in red (Figure 4b), the acquisition function identifies the best ligand as the second candidate to be tested (fifth total ligand, including the three included in the initial training set), faster than the original experimental optimization procedure. From that point forward, one additional ligand is (incorrectly) predicted to bring potential improvement; however, given the significant amount of uncertainty, the additional specimen ultimately did not demonstrate improved selectivity. At this point, the stop criterion was met as no other ligand in the pool was predicted to provide further improvement, in agreement with experimental observations.

Compared to the original purely experimental screening, using the BO pipeline reduced the total number of reactions performed by a factor of 3 (6 vs 19). Thus, BO succeeds, even in the low-data regime, at rapidly identifying the best ligand from the candidate pool while avoiding wasteful experiments.

With these promising results in hand, we screened ligands reported in the CP, CC, and DA reactions (Scheme 1) to test their enantioselectivity for the OA reaction. Figure 5a (top left) shows the best ligand found experimentally, as well as the top three “not-yet-sampled” ligand candidates derived from the other three reaction classes that were predicted by the BRR. As each of these ligand structures closely matches those previously tested experimentally, unsurprisingly, ligands (2–4) are predicted to yield only minimal improvement over the current best ligand (1) from the OA set. Since these “Literature Pool candidate” ligands are so structurally similar to those found in the OA pool, their experimental testing corresponds to a “low-risk, low-reward” situation, where the model is reliable, but potential improvements in selectivity are anticipated to be minor.

Figure 5.

Predictions and analysis of literature and CSD-extracted ligands for the OA reaction. (a) Top left: the best ligand found experimentally. Top right: the top three EI candidates from pool-based predictions for the reaction using the ligands from the three remaining literature data sets. Bottom: four diverse candidate ligands from the CSD which exhibit a high EI score. The predicted ΔΔG⧧ and its uncertainty are given. The used model is given at the bottom. (b) PCA map of the candidate ligands using the same embedding as in Figure 1b (gray points). The coloring corresponds to EI scores (truncated to 10–6 for clarity). Red numbers correspond to structures in panel (a). aOptimized reaction conditions with this ligand yield 90% ee.

On the other hand, searching for a much broader range of structures, such as the 312 bidentate chiral ligands extracted from the CSD (see Section 2.1), constitutes a much different approach. In this “high-risk, high-reward” situation, the model is highly prone to errors (due to having never seen these types of structures) but can serve as a means to move toward new regions of ligand space that the model finds promising. As an example, four newly identified ligand classes (5–8) each possessing distinct electronic properties (i.e., negative charges) from the original sets of tested ligands, as well as high rigidities (for 7 and 8), are shown in Figure 5a “CSD Pool candidates”. Here, the presence of oxygen- and electron-rich nitrogen atoms imparts substantially higher NBO charges than those of the previously tested ligands, which leads to higher predicted enantioselectivities (along with higher predicted uncertainties!) according to the linear model.

To assess this increase in diversity, these “high-risk, high-reward” CSD ligands were plotted with the previously discussed dimensionality reduction embedding (Figure 5b). In general, identified literature-extracted ligands (1–4) are found close to the bottom of the map. 7 and 8 are situated near the α-diimine and 1,2-BOX regions as they most closely resemble these classes. On the other hand, the most promising candidates (with high EI scores) 5 and 6, which belong to new classes of ligands within the CSD set, were unexplored in the experimental ligand screenings.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we introduced a general workflow for constructing linear models from small numbers of screening experiments that predict enantioselectivity in reactions involving bidentate ligands. Data sets comprising four different reaction classes (totaling 100 bidentate ligands belonging to seven ligand families) were curated to validate this approach and supplemented with the BDL-Cu-2023 data set as a pool for further ligand optimization. Our workflow retrieves the best possible linear model established from a combination of electronic, steric, and (critically important but frequently overlooked) topological features that were determined using BRR. By coupling BRR with BO, we were able to efficiently screen ligands, even in limited data scenarios, which allowed design principles to be extracted and new ligands to be proposed for the oxy-alkynylation reaction. Overall, the approach presented here enables researchers to optimize ligand selection and design at any stage of experimentation, resulting in more efficient and cost-effective enantioselective reaction development.

5. Computational Details

DFT computations of ligands were done at the PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP level using Gaussian16.100−86 For ligands extracted from the literature, 3D coordinates were generated using OpenBabel (version 2.4.1)88 and then optimized at the GFN2-xTB level87 before final optimization with DFT. The desired structure (chelating groups oriented toward the metal atom) was obtained by adding CuCl2 to the molecules before the optimization, as previously reported (see Table S1 for comparison with CuCl geometries).27,57 Ligands used in the Ni-catalyzed reactions were optimized with CuCl2 and NiF2 for comparison (see Table S2). Similar to Cu(I) and Cu(II), the rmsd for the tested structures was found to be lower than 1 Å on average. All electronic features, including NBO analyses,89 were performed on the metal-free ligand structures. Atoms for the different NBO charges (atom itself and lone-pair) were defined based on distance to the metal center. The optimized or crystal structure coordinates were used to compute the steric features and build the molecular graphs. For the steric features, both libarvo90,92 and Morfeus91 were used. Features derived from the molecular graph were generated using the newly developed Moltop Python package. Whenever bond orders are required for a specific feature (such as the Crest flexibility index), these have to be defined explicitly. Supported bond orders currently include ones from NBO analyses, xTB, and RDkit. All Moltop instructions and scripts used in this study are available on GitHub at https://github.com/lcmd-epfl/rafbl and as part of the NaviCat platform at https://github.com/lcmd-epfl/NaviCat. Additionally, the generated data can be explored interactively in the MaterialsCloud repository https://doi.org/10.24435/materialscloud:c0-7z. The Sklearn package93 was used for linear models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank EPFL for computational resources. This publication was created as part of NCCR Catalysis (grant no. 180544), a National Centre of Competence in Research funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. We also thank Dr. Simone Gallarati, Dr. Nieves P. Ramirez, and Dr. Stefano Nicolai for fruitful discussions and Prof. Durga Hari for the unreported experiments.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.4c02452.

Description and details of data sets; discussion of the ligand geometry optimization; details of ligand featurization methods including complete list of features; and additional model details and related discussion (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ahneman D. T.; Estrada J. G.; Lin S.; Dreher S. D.; Doyle A. G. Predicting reaction performance in C–N cross-coupling using machine learning. Science 2018, 360, 186–190. 10.1126/science.aar5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahrt A. F.; Henle J. J.; Rose B. T.; Wang Y.; Darrow W. T.; Denmark S. E. Prediction of higher-selectivity catalysts by computer-driven workflow and machine learning. Science 2019, 363, eaau5631 10.1126/science.aau5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahrt A. F.; Athavale S. V.; Denmark S. E. Quantitative Structure–Selectivity Relationships in Enantioselective Catalysis: Past, Present, and Future. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 1620–1689. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A.; Keane A.; Dumesic J. A.; Huber G. W.; Zavala V. M. A machine learning framework for the analysis and prediction of catalytic activity from experimental data. Appl. Catal., B 2020, 263, 118257. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik H. J.; Sigman M. S. Advancing Discovery in Chemistry with Artificial Intelligence: From Reaction Outcomes to New Materials and Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2335–2336. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. M.; Kingston C.; Toste F. D.; Sigman M. S. Data Science Meets Physical Organic Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3136–3148. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams W. L.; Zeng L.; Gensch T.; Sigman M. S.; Doyle A. G.; Anslyn E. V. The Evolution of Data-Driven Modeling in Organic Chemistry. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 1622–1637. 10.1021/acscentsci.1c00535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallarati S.; Fabregat R.; Laplaza R.; Bhattacharjee S.; Wodrich M. D.; Corminboeuf C. Reaction-based machine learning representations for predicting the enantioselectivity of organocatalysts. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 6879–6889. 10.1039/D1SC00482D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Żurański A. M.; Martinez Alvarado J. I.; Shields B. J.; Doyle A. G. Predicting Reaction Yields via Supervised Learning. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1856–1865. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueffel J. A.; Sperger T.; Funes-Ardoiz I.; Ward J. S.; Rissanen K.; Schoenebeck F. Accelerated dinuclear palladium catalyst identification through unsupervised machine learning. Science 2021, 374, 1134–1140. 10.1126/science.abj0999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose B. T.; Timmerman J. C.; Bawel S. A.; Chin S.; Zhang H.; Denmark S. E. High-Level Data Fusion Enables the Chemoinformatically Guided Discovery of Chiral Disulfonimide Catalysts for Atropselective Iodination of 2-Amino-6-arylpyridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 22950–22964. 10.1021/jacs.2c08820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplaza R.; Gallarati S.; Corminboeuf C. Genetic Optimization of Homogeneous Catalysts. Chem.: Methods 2022, 2, e202100107 10.1002/cmtd.202100107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallarati S.; Laplaza R.; Corminboeuf C. Harvesting the fragment-based nature of bifunctional organocatalysts to enhance their activity. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 4041–4051. 10.1039/D2QO00550F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaller P.; Vaucher A. C.; Laplaza R.; Bunne C.; Krause A.; Corminboeuf C.; Laino T. Machine intelligence for chemical reaction space. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1604 10.1002/wcms.1604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torres J. A. G.; Lau S. H.; Anchuri P.; Stevens J. M.; Tabora J. E.; Li J.; Borovika A.; Adams R. P.; Doyle A. G. A Multi-Objective Active Learning Platform and Web App for Reaction Optimization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 19999–20007. 10.1021/jacs.2c08592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betinol I. O.; Kuang Y.; Reid J. P. Guiding Target Synthesis with Statistical Modeling Tools: A Case Study in Organocatalysis. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 1429–1433. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c04134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson J. J.; van Dijk L.; Timmerman J. C.; Grosslight S.; Walroth R. C.; Gosselin F.; Püntener K.; Mack K. A.; Sigman M. S. Data-Driven Multi-Objective Optimization Tactics for Catalytic Asymmetric Reactions Using Bisphosphine Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 110–121. 10.1021/jacs.2c08513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-Z.; Wang Z.-H.; Eshel I. L.; Sun B.; Liu D.; Gu Y.-C.; Milo A.; Mei T.-S. Nickel/biimidazole-catalyzed electrochemical enantioselective reductive cross-coupling of aryl aziridines with aryl iodides. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2322. 10.1038/s41467-023-37965-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieth-Kalthoff F.; Sandfort F.; Kühnemund M.; Schäfer F. R.; Kuchen H.; Glorius F. Machine Learning for Chemical Reactivity: The Importance of Failed Experiments. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202204647 10.1002/anie.202204647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleinitz J.; Langevin M.; Smail Y.; Wehnert B.; Grimaud L.; Vuilleumier R. Machine Learning Yield Prediction from NiCOlit, a Small-Size Literature Data Set of Nickel Catalyzed C–O Couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14722–14730. 10.1021/jacs.2c05302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney M. P.; Coley C. W.; Genheden S.; Carson N.; Helquist P.; Norrby P.-O.; Wiest O. Negative Data in Data Sets for Machine Learning Training. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 2945–2947. 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c01282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski M. C.; Dixon S. L.; Panda M.; Lauri G. Quantum Mechanical Models Correlating Structure with Selectivity: Predicting the Enantioselectivity of β-Amino Alcohol Catalysts in Aldehyde Alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6614–6615. 10.1021/ja0293195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuan P.-W.; Ianni J. C.; Kozlowski M. C. Is the A-Ring of Sparteine Essential for High Enantioselectivity in the Asymmetric Lithiation-Substitution of N-Boc-pyrrolidine?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15473–15479. 10.1021/ja046321i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville J. L.; Andrews B. I.; Lygo B.; Hirst J. D. Computational screening of combinatorial catalyst libraries. Chem. Commun. 2004, 1410–1411. 10.1039/b402378a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid J. P.; Sigman M. S. Holistic prediction of enantioselectivity in asymmetric catalysis. Nature 2019, 571, 343–348. 10.1038/s41586-019-1384-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S. H.; Borden M. A.; Steiman T. J.; Wang L. S.; Parasram M.; Doyle A. G. Ni/Photoredox-Catalyzed Enantioselective Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Styrene Oxides with Aryl Iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 15873–15881. 10.1021/jacs.1c08105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth J.; Sigman M. S. Linear Regression Model Development for Analysis of Asymmetric Copper-Bisoxazoline Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 3916–3922. 10.1021/acscatal.1c00531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. C.; Goetz A. E.; Bahamonde A.; McWilliams J. C.; Sigman M. S. Predicting relative efficiency of amide bond formation using multivariate linear regression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119, e2118451119 10.1073/pnas.2118451119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota R. C.; Liu W.; Bacsa J.; Davies H. M. L.; Sigman M. S. Mechanistically Guided Workflow for Relating Complex Reactive Site Topologies to Catalyst Performance in C–H Functionalization Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 1881–1898. 10.1021/jacs.1c12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustosa D. M.; Milo A. Mechanistic Inference from Statistical Models at Different Data-Size Regimes. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 7886–7906. 10.1021/acscatal.2c01741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lustosa D. M.; Barkai S.; Domb I.; Milo A. Effect of Solvents on Proline Modified at the Secondary Sphere: A Multivariate Exploration. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 1850–1857. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c02778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand D. J.; Fey N. Computational Ligand Descriptors for Catalyst Design. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 6561–6594. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand D. J.; Fey N. Building a Toolbox for the Analysis and Prediction of Ligand and Catalyst Effects in Organometallic Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 837–848. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Żurański A. M.; Wang J. Y.; Shields B. J.; Doyle A. G. Auto-QChem: an automated workflow for the generation and storage of DFT calculations for organic molecules. React. Chem. Eng. 2022, 7, 1276–1284. 10.1039/d2re00030j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago C. B.; Guo J.-Y.; Sigman M. S. Predictive and mechanistic multivariate linear regression models for reaction development. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 2398–2412. 10.1039/C7SC04679K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkowitz K. B.; Pradhan M. Computational Studies of Chiral Catalysts: A Comparative Molecular Field Analysis of an Asymmetric Diels-Alder Reaction with Catalysts Containing Bisoxazoline or Phosphinooxazoline Ligands. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 4648–4656. 10.1021/jo0267697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville J. L.; Lovelock K. R. J.; Wilson C.; Allbutt B.; Burke E. K.; Lygo B.; Hirst J. D. Exploring Phase-Transfer Catalysis with Molecular Dynamics and 3D/4D Quantitative Structure-Selectivity Relationships. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 971–981. 10.1021/ci050051l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguado-Ullate S.; Guasch L.; Urbano-Cuadrado M.; Bo C.; Carbó J. J. 3D-QSPR models for predicting the enantioselectivity and the activity for asymmetric hydroformylation of styrene catalyzed by Rh-diphosphane. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 1694–1704. 10.1039/c2cy20089a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart N. I.; Zahrt A. F.; Henle J. J.; Denmark S. E. Dreams, False Starts, Dead Ends, and Redemption: A Chronicle of the Evolution of a Chemoinformatic Workflow for the Optimization of Enantioselective Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2041–2054. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S. Molecular field analysis for data-driven molecular design in asymmetric catalysis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 6057–6071. 10.1039/D2OB00228K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensch T.; dos Passos Gomes G.; Friederich P.; Peters E.; Gaudin T.; Pollice R.; Jorner K.; Nigam A.; Lindner-D’Addario M.; Sigman M. S.; Aspuru-Guzik A. A Comprehensive Discovery Platform for Organophosphorus Ligands for Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 1205–1217. 10.1021/jacs.1c09718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.; Li Y.; Tian Q.; You T. QSAR Study of Catalytic Asymmetric Reactions with Topological Indices. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 1876–1881. 10.1021/ci034119d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.; Li D.; Wen J.; You T. QSAR study of the enantiomeric excess in asymmetric catalytic reactions with topological indices and an artificial neural network. J. Mol. Model. 2006, 13, 91–97. 10.1007/s00894-006-0126-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Jiwu W.; Mingzong L.; You T. Calculation on enantiomeric excess of catalytic asymmetric reactions of diethylzinc addition to aldehydes with topological indices and artificial neural network. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2006, 258, 191–197. 10.1016/j.molcata.2006.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tipping M. E. Sparse Bayesian Learning and the Relevance Vector Machine. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2001, 1, 211–244. [Google Scholar]

- Häse F.; Roch L. M.; Kreisbeck C.; Aspuru-Guzik A. Phoenics: A Bayesian Optimizer for Chemistry. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 1134–1145. 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brethomé A. V.; Paton R. S.; Fletcher S. P. Retooling Asymmetric Conjugate Additions for Sterically Demanding Substrates with an Iterative Data-Driven Approach. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 7179–7187. 10.1021/acscatal.9b01814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields B. J.; Stevens J.; Li J.; Parasram M.; Damani F.; Alvarado J. I. M.; Janey J. M.; Adams R. P.; Doyle A. G. Bayesian reaction optimization as a tool for chemical synthesis. Nature 2021, 590, 89–96. 10.1038/s41586-021-03213-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorayev P.; Russo D.; Tibbetts J. D.; Schweidtmann A. M.; Deutsch P.; Bull S. D.; Lapkin A. A. Multi-objective Bayesian optimisation of a two-step synthesis of p-cymene from crude sulphate turpentine. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 247, 116938. 10.1016/j.ces.2021.116938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman R. J.; Aldeghi M.; Häse F.; Aspuru-Guzik A. Bayesian optimization with known experimental and design constraints for chemistry applications. Digital Discovery 2022, 1, 732–744. 10.1039/D2DD00028H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough K. E.; King D. S.; Chheda S. P.; Ferrandon M. S.; Goetjen T. A.; Syed Z. H.; Graham T. R.; Washton N. M.; Farha O. K.; Gagliardi L.; Delferro M. High-Throughput Experimentation, Theoretical Modeling, and Human Intuition: Lessons Learned in Metal-Organic-Framework-Supported Catalyst Design. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 266–276. 10.1021/acscentsci.2c01422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom G.; Hickman R. J.; Zinzuwadia A.; Mohajeri A.; Sanchez-Lengeling B.; Aspuru-Guzik A. Calibration and generalizability of probabilistic models on low-data chemical datasets with DIONYSUS. Digital Discovery 2023, 2, 759–774. 10.1039/D2DD00146B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton A. D.; Pyzer-Knapp E. O.; Purdie M.; Jones M. F.; Barthelme A.; Pavey J.; Kapur N.; Chamberlain T. W.; Blacker A. J.; Bourne R. A. Bayesian Self-Optimization for Telescoped Continuous Flow Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202214511 10.1002/anie.202214511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahrt A. F.; Rose B. T.; Darrow W. T.; Henle J. J.; Denmark S. E. Computational methods for training set selection and error assessment applied to catalyst design: guidelines for deciding which reactions to run first and which to run next. React. Chem. Eng. 2021, 6, 694–708. 10.1039/D1RE00013F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart N. I.; Saunthwal R. K.; Wellauer J.; Zahrt A. F.; Schlemper L.; Shved A. S.; Bigler R.; Fantasia S.; Denmark S. E. A machine-learning tool to predict substrate-adaptive conditions for Pd-catalyzed C–N couplings. Science 2023, 381, 965–972. 10.1126/science.adg2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari D. P.; Waser J. Enantioselective Copper-Catalyzed Oxy-Alkynylation of Diazo Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8420–8423. 10.1021/jacs.7b04756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguado-Ullate S.; Urbano-Cuadrado M.; Villalba I.; Pires E.; García J. I.; Bo C.; Carbó J. J. Predicting the Enantioselectivity of the Copper-Catalysed Cyclopropanation of Alkenes by Using Quantitative Quadrant-Diagram Representations of the Catalysts. Chem.—Eur J. 2012, 18, 14026–14036. 10.1002/chem.201201135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. A.; Lectka T.; Miller S. J. Bis(imine)-copper(II) complexes as chiral lewis acid catalysts for the Diels-Alder reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 7027–7030. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)61588-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies I. W.; Gerena L.; Castonguay L.; Senanayake C. H.; Larsen R. D.; Verhoeven T. R.; Reider P. J. The influence of ligand bite angle on the enantioselectivity of copper(II)-catalysed Diels-Alder reactions. Chem. Commun. 1996, 1753–1754. 10.1039/CC9960001753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Mathivanan P.; Cappiello J. Conformationally constrained bis(oxazoline) derived chiral catalyst: A highly effective enantioselective Diels-Alder reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 3815–3818. 10.1016/0040-4039(96)00721-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies I. W.; Gerena L.; Cai D.; Larsen R. D.; Verhoeven T. R.; Reider P. J. A conformational toolbox of oxazoline ligands. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 1145–1148. 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00010-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. A.; Miller S. J.; Lectka T.; von Matt P. Chiral Bis(oxazoline)copper(II) Complexes as Lewis Acid Catalysts for the Enantioselective Diels-Alder Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 7559–7573. 10.1021/ja991190k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemasa S.; Adachi K.; Yamamoto H.; Wada E. Bisoxazoline and Bioxazoline Chiral Ligands Bearing 4-Diphenylmethyl Shielding Substituents. Diels-Alder Reaction of Cyclopentadiene with 3-Acryloyl-2-oxazolidinone Catalyzed by the Aqua Nickel(II) Complex. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2000, 73, 681–687. 10.1246/bcsj.73.681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary P.; Krosveld N. P.; De Jong K. P.; van Koten G.; Klein Gebbink R. J. Facile and rapid immobilization of copper(II) bis(oxazoline) catalysts on silica: application to Diels-Alder reactions, recycling, and unexpected effects on enantioselectivity. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 3177–3180. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groom C. R.; Allen F. H. The Cambridge Structural Database in Retrospect and Prospect. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 662–671. 10.1002/anie.201306438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groom C. R.; Bruno I. J.; Lightfoot M. P.; Ward S. C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 171–179. 10.1107/S2052520616003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vela S.; Laplaza R.; Cho Y.; Corminboeuf C. cell2mol: encoding chemistry to interpret crystallographic data. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 188. 10.1038/s41524-022-00874-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poater A.; Ragone F.; Mariz R.; Dorta R.; Cavallo L. Comparing the Enantioselective Power of Steric and Electrostatic Effects in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis. Chem.—Eur J. 2010, 16, 14348–14353. 10.1002/chem.201001938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener H. Structural Determination of Paraffin Boiling Points. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69, 17–20. 10.1021/ja01193a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya H. Topological Index. A Newly Proposed Quantity Characterizing the Topological Nature of Structural Isomers of Saturated Hydrocarbons. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1971, 44, 2332–2339. 10.1246/bcsj.44.2332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban A. T. Highly discriminating distance-based topological index. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1982, 89, 399–404. 10.1016/0009-2614(82)80009-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kier L. B. A Shape Index from Molecular Graphs. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 1985, 4, 109–116. 10.1002/qsar.19850040303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kier L. B. Shape Indexes of Orders One and Three from Molecular Graphs. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 1986, 5, 1–7. 10.1002/qsar.19860050102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kier L. B. Distinguishing Atom Differences in a Molecular Graph Shape Index. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 1986, 5, 7–12. 10.1002/qsar.19860050103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kier L. B. An Index of Molecular Flexibility from Kappa Shape Attributes. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 1989, 8, 221–224. 10.1002/qsar.19890080307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall L. H.; Kier L. B. Determination of Topological Equivalence in Molecular Graphs from the Topological State. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 1990, 9, 115–131. 10.1002/qsar.19900090207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kier L. B.; Hall L. H. A Differential Molecular Connectivity Index. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 1991, 10, 134–140. 10.1002/qsar.19910100208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall L. H.; Mohney B.; Kier L. B. The Electrotopological State: An Atom Index for QSAR. Quant. Struct.-Act. Relat. 1991, 10, 43–51. 10.1002/qsar.19910100108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caron G.; Digiesi V.; Solaro S.; Ermondi G. Flexibility in early drug discovery: focus on the beyond-Rule-of-5 chemical space. Drug Discovery Today 2020, 25, 621–627. 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisanick W.; Cross K. P.; Rusinko A. Characteristics of computer-generated 3D and related molecular property data for CAS registry substances. Tetrahedron Comput. Methodol. 1990, 3, 635–652. 10.1016/0898-5529(90)90163-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pracht P.; Bohle F.; Grimme S. Automated exploration of the low-energy chemical space with fast quantum chemical methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 7169–7192. 10.1039/C9CP06869D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements H. D.; Flynn A. R.; Nicholls B. T.; Grosheva D.; Lefave S. J.; Merriman M. T.; Hyster T. K.; Sigman M. S. Using Data Science for Mechanistic Insights and Selectivity Predictions in a Non-Natural Biocatalytic Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 17656–17664. 10.1021/jacs.3c03639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. R.; Schonlau M.; Welch W. J. Efficient Global Optimization of Expensive Black-Box Functions. J. Glob. Optim. 1998, 13, 455–492. 10.1023/A:1008306431147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Ernzerhof M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo C.; Barone V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. 10.1063/1.478522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Ehrlich S.; Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; et al. Gaussian 16. Revision C.01; Gaussian Inc: Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Bannwarth C.; Ehlert S.; Grimme S. GFN2-xTB—An Accurate and Broadly Parametrized Self-Consistent Tight-Binding Quantum Chemical Method with Multipole Electrostatics and Density-Dependent Dispersion Contributions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1652–1671. 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b01176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle N. M.; Banck M.; James C. A.; Morley C.; Vandermeersch T.; Hutchison G. R. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminf. 2011, 3, 33. 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D.; Reed A. E.; Carpenter J. E.; Weinhold F.. NBO. Version 3.1, 2001.

- Buša J.; Džurina J.; Hayryan E.; Hayryan S.; Hu C.-K.; Plavka J.; Pokorný I.; Skřivánek J.; Wu M.-C. ARVO: A Fortran package for computing the solvent accessible surface area and the excluded volume of overlapping spheres via analytic equations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2005, 165, 59–96. 10.1016/j.cpc.2004.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorner K.MORFEUS: molecular features for machine learning.2024https://digital-chemistry-laboratory.github.io/morfeus/ (accessed 2024-05-15).

- Laplaza R.libarvo: library to compute molecular surfaces and volumes, 2024. https://github.com/rlaplaza/libarvo (accessed 2024-05-15).

- Pedregosa F.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.