Abstract

The mind has been traditionally conceived as a set of differentiated, compartmentalized cognitive elements. However, understanding everyday, naturalistic cognition across brain health and disease entails major challenges. How can mainstream approaches be extended to cognition in the wild? Pragmatic, methodological, disease-related, and theoretical turns are proposed for future scientific development.

Keywords: situated cognition, cognitive neuroscience, brain dynamics, brain health, embodiment, cognition in the wild

The mind’s golden cage

From its early philosophical origins, to cybernetics, to the computer metaphor, to the cognitive revolution, and finally to its current marriage with neuroscience, the cognitive sciences developed a powerful heuristic: Divide cognition and conquer the mind. The mind has generally been conceived as a set of specific, compartmentalized cognitive elements. Reified entities were initially proposed for reasoning, intelligence, and memory. Later theoretical developments (e.g. embodied, extended, enactive, distributed, situated cognition), and multilevel approaches strengthened our understanding of emotion, social interaction, body, and context [1]. The mind became situated, although still compartmentalized.

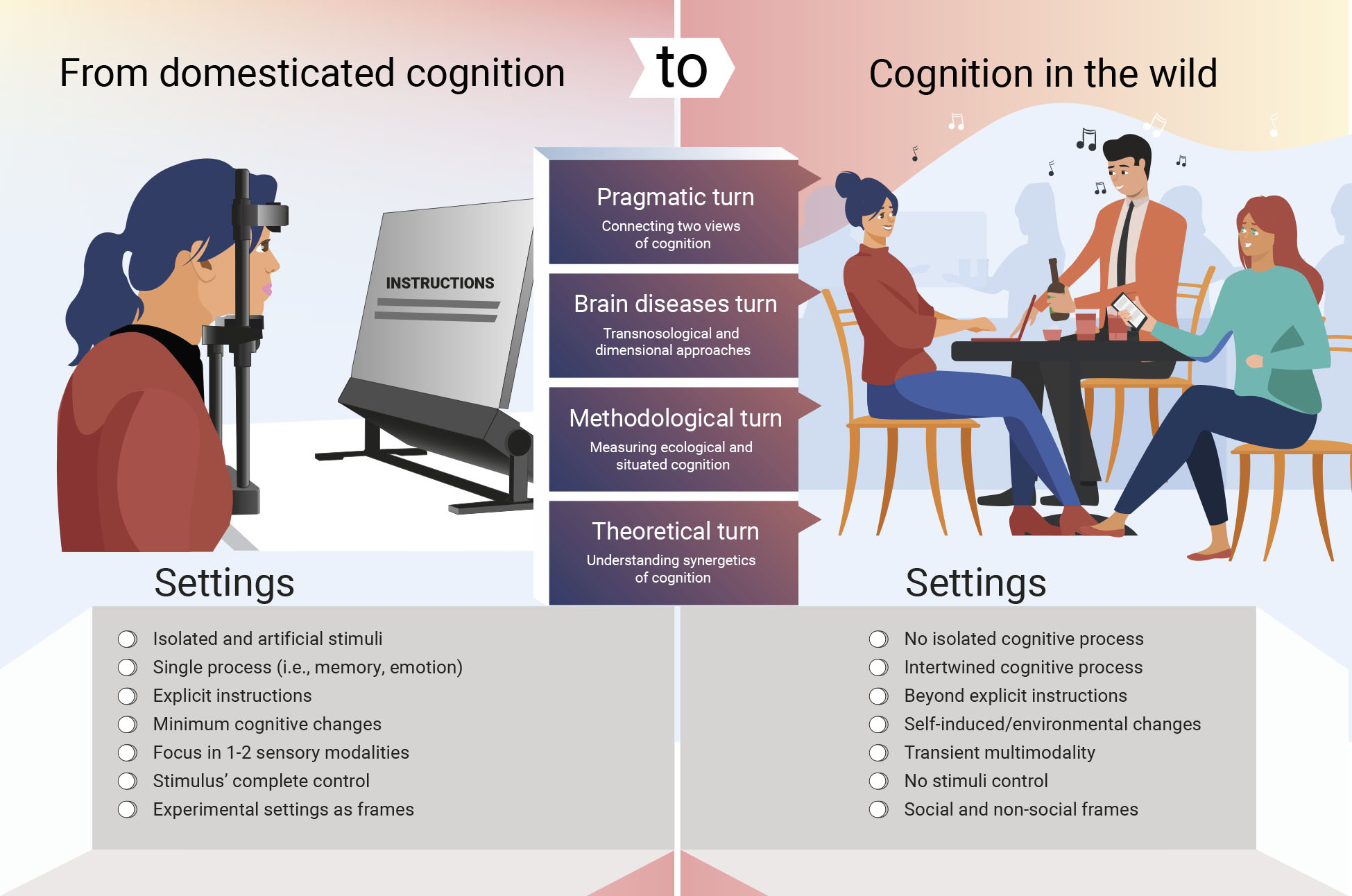

Mainstream cognitive science has made progress by domesticating cognition (Figure 1, left), an approach following naturally from the conceptualization of the mind as a set of isolated mechanisms. In most experiments, participants are passively exposed to fixed stimuli. One or two cognitive processes are assessed via one or two modalities, with strict control over tasks and participants’ behavior. This provides accurate correlates for fragments of methodically decomposed elements, such as bodiless faces, situation-independent words, or intention-blind interactions [2]. Most contemporary theories are based on applications of this analytic approach.

Figure 1. From domesticated cognition to cognition in the wild.

The domesticated cognition (left panel) as observed in standard experiments. Participants passively respond to a specific, predetermined set of stimuli. Explicit instructions include to focus on the task and stimuli, to not move, and to avoid thinking or doing anything unrelated with the task. Typically, a single process (i.e., memory) is being evaluated. Stimuli entangle one or two modalities with strict control of stimulus properties. Isolated cognitive processes are being measured. Conversely, cognition in the wild (right panel) involves multiple processes spontaneously intertwined, unrestricted by explicit instructions, and with undetermined internal (cognitive) and external (environment) changes. The stream of cognitive processes is usually multimodal and multidimensional, and the environment does not provide a fixed stimulus control nor invariable social/non-social frame. Connecting domesticated cognition with cognition in the wild (center panel) may involve systematic and progressive pragmatic, brain-disease, methodological and theoretical turns.

Although enormous knowledge about segregated phenomena that rarely manifest as such outside the laboratory has been accumulated, this success has become a golden cage. Domesticating cognition has yielded insights into fragments of the mind, but poses challenges to understanding cognition in everyday life.

Cognition in the wild, uncharted

Imagine a typical interaction with a parental figure and label your internal activity: you probably engaged in a blending of audiovisual attention, sensorimotor processing, memory, language comprehension/production, imaginary processing, body/face recognition, interoception, and mentalization. Even when internally simulated, processes traditionally classified as cognition, emotion, interoception, and so forth are spontaneously intertwined. Thus, although cognitive element may be phenomenologically distinguished in the laboratory, this can obscure how different processes blend in the wild [2, 3]. In this way, cognition in the wild differs critically from domesticated cognition. It involves synergetic blending and self- and environmental-induced changes rather than instructions.

A trade-off between experimental control and ecological validity pervades the field. The greater the experimental control, the greater the distance from cognition in the wild. Similarly, associations between brain structure and function are complex and often nonlinear [3, 4]. In complex phenomena, no single cognitive process seems uniquely related to a single brain area or process, and vice versa. Although network science provides a more dynamical view, the problem stands: Is the salience or the executive network related to a particular process? [3, 4]. Links between experimental and naturalistic cognition are fragile, limiting our understanding of brain-behavior associations.

Theories of isolated phenomena cannot adequately capture synergetic processes [3]. Generalist frameworks (i.e., predictive coding; dynamical system approaches to cognition[5]) have been applied to a variety of cognitive processes. Unfortunately, these “theory of everything” [6] approaches are usually more successful as models of a specific (or few) domain(s) than cognitive synergies. Similarly, neurocognitive theories have typically favored causal (linear) explanations, which are not well-suited to assess individual differences and contextual dependencies under naturalistic settings [7]. Although multilevel explanations are encouraged in the field of embodiment and social neuroscience, in reality, most cases are not truly multilevel (they involve simple associations between neural and cognitive measures). Cognitive science continues to create models of specific processes fit for observation in laboratory settings, but theories assessing cognitive synergies are rare.

Cognition in brain health and disease

Although brain health involves the appropriate coordination of cognitive, emotional, social and behavioral functions, it is typically understood via disease models developed by clinical disciplines traditionally rooted in domesticated cognition.

Neurological and psychiatric disorders are generally associated with specific cognitive deficits even though most brain diseases do not entail a single cognitive deficit linked to one specific dysfunction (see Box 1). For instance, mentalization deficits present in autism are accompanied by impairments in working memory and executive functions. Meanwhile, motor disorders (i.e., Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) present deficits in social cognition. In dementia, disruptions of the orchestrating dynamics lead to disintegration of cognition and identity. Cognitive deficits across diseases are not only transdiagnostic but transcognitive.

Box 1. Nonlinear mapping of brain and cognition across diseases.

Brain diseases provide links between unique cognitive impairments and structural brain(dis)function. However, revisited evidence of one-to-one mappings are more challenging than initially anticipated (Table 1). The “lesion model” surpasses correlative evidence of neuroimaging although these models have accentuated simple associations between one cognitive deficit and a specific damage [2]. Present evidence supports the degeneracy principle [10], where a similar impaired cognition across diseases is related to disparate cellular, molecular, regional, and network heterogeneity. For instance, moral cognition deficits are observed in patients with localized vmPFC damage, diffuse frontotemporal neurodegeneration, white-matter abnormalities, mesolimbic dopaminergic or serotonergic dysfunctions. The opposite is also true: disparate cognitive deficits are observed with similar biological impairments. The same mutation (C9orf72) can lead to either to systematic social impairments (i.e., behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia) or to a predominantly motor disease (i.e., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Insular lesions are related to deficits of gustatory, olfactory, auditory, somatosensory, and multimodal perception, but also mood, action, language, empathy, emotion, executive functions, or addiction. Assessing one-to-one mappings is required to address domesticated cognition. Conversely, cognition in the wild calls for a dynamic and synergetic assessment of brain and behavior.

Furthermore, a clinical neuropsychological setting provides an unchanged, structured, and highly predictive scenario. Consequently, cognitive performance does not always replicate cognition in the wild [8] and we do not know whether neuropsychological assessments have real-life significance for the patients.

Freeing cognition

Continuing on the aforementioned trajectories risks accumulating knowledge that does not capture naturalistic cognition [9]. How can the limits of the domesticated mind be surpassed to better assess cognition in the wild? I propose four avenues for progressive development (Figure 1, center).

Pragmatic turn

A first modest step is to better connect current experimental advances with naturalistic cognition. This necessitates expanding classical internal validation processes (control of stimulus, conditions, confounding) towards identifying specific cognitive tasks (i.e., bona fide cases of compartmentalized cognition) that predict naturalistic cognition. External confirmation via double validation (in the lab and the field) may underscore the relevance of certain experimental approaches. Controlled results (i.e., different experiments on working memory performance) can be used to predict performance in naturalistic settings (i.e., multitasking during social-ecological interactions). Well-powered designs combining controlled and naturalistic experiments are needed to assess individual and contextual differences, and to estimate generalizability from controlled to naturalistic scenarios.

Brain-diseases turn

Both clinical and cognitive sciences can benefit from more dimensional (transdiagnostic) approaches to brain diseases. For the clinical sciences, cognitive commonalities across and within psychiatric and neurological disorders may better reflect the biology of disease. The research Domain Criteria represents an initial attempt in psychiatry to promote the dimensional study of cognitive deficits across conditions, but it is still based on compartmentalized processes. Accordingly, physiopathological models based on the degeneracy principle (see Box 1 [10]) that assess fuzzy, non-categorical, and transnosological cognitive deficits are better positioned to tackle the large disease heterogeneity. Although preliminary, synergetic models of allostasis and neurodegeneration capture multiple brain (molecular pathways, atrophy, connectivity) and cognitive (executive, social, interoceptive, inhibitory) dynamics. For cognitive science, the (a) combination of dimensional physiopathology with novel data science approaches, (b) ecological assessments of cognitive dynamics, and (c) development of more complex methods connecting different mechanisms can bring synergetic cognition into the context of brain diseases.

Methodological turn

The design of tasks resembling everyday cognition is critical. Different methods have started to avoid using repetitive, artificial stimuli and oversimplified scenarios [11]. Examples include natural speech analysis, multisensory evoked responses, hyperscanning of interacting individuals, citizen science large-scale data designs using naturalistic settings, and virtual reality. Future research should parametrically incorporate spontaneous cognitive changes and environmental demands, which modify settings in natural contexts. Technical developments such as machine learning of multivariate data, decoding of naturalistic actions, or self-organizing network analysis, will help to progressively approach ecological phenomena [2, 3]. Finally, advances in naturalistic designs, including wearable, remote, multisource recording technologies, and digital cognition may favor a better understanding of cognition in the wild.

Theoretical turn

Theorization on synergic cognitive phenomena should avoid strict cognitive categories in favor of transient, dynamic, anticipatory processes shaped by neural, bodily, and environmental architectures. This requires moving beyond current embodied and situated approaches based on compartmentalized processes. Although presently challenging, future theorization may assess cross-phenomenological synergies [2]. Each cognitive element must truly be considered a process that (a) emerges from the interaction with other cognitive processes, (b) is transient and dynamical according to contextual backgrounds, and (c) presents high heterogeneity depending on (a) and (b).

Behaviorally informed emergentist approaches may also help move us beyond a reflexive-passive view of cognitive processes [7]. Assessing synergetic phenomena [3] with whole-brain dynamical modeling and theorization can be a good starting point. In some models [12] the orchestration of widely distributed (cognitive and brain) states is supported by transient and emergent integrations of intermixed processes. The self-organization of multiple cognitive processes during naturalistic tasks can be modelled with global transient dynamics [2, 3],

Finally, boundaries between disciplines require reconsideration. Transdisciplinary approaches combat academic compartmentalization and may lead to more holistic insights about the mind. The cognitive revolution developed such an approach, although based in the metaphor of the mind as a computer. A transdisciplinary approach based around cognition in the wild may better resemble naturalistic cognition.

Concluding remarks

Although shifts have already begun in some areas, a systematic four-fold turn towards naturalistic cognition as outlined here may bring the mainstream of cognitive science to the doorstep of cognition in the wild. Doing so may help science transcend the mind’s golden cage.

Table 1.

Reconsideration of classical mappings of brain structure and function

| Patient/Condition | Structural damage | Domain | Structure or domain revisited |

|---|---|---|---|

| H.M. | Hippocampus (bilateral resection) | Memory deficits | Partially preserved hippocampus, other diffuse pathology, and lesions in distant regions (orbitofrontal cortex). |

|

| |||

| bvFTD | FTI degeneration | Social cognition deficits | Cognitive (memory, executive functions), mood (depression, apathy), and behavioral (disinhibition) impairments. |

|

| |||

| SS lesions | SS cortex lesions | Somatosensory sensing deficits | Somatosensory cortex involved in body model, contextual update, memory, motor output, and body simulations. |

|

| |||

| Split brain | callosotomy | Verbal vs perception deficits | Left-right modularity has been outdated by dynamical whole-brain interactions. |

|

| |||

| PD | Basal ganglia neurodegeneration | Motor skills impairment | Brain systemic disease and cognitive deficits (action language, executive functions, social cognition, mood). |

|

| |||

| Phineas Gage | Ventromedial prefrontal lesion | Decision-making deficits | Extensive damage of grey matter and connections beyond the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. |

|

| |||

| Tan | Broca lesion | Language production deficits | Additional damage to insular areas and disruption of connections projecting to distant regions. |

bvFTD: Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; FTI: Fronto-temporo-insular; Parkinson’s disease: PD; SS: Somatosensory

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the feedback of an early version from the TICS’ Editor in Chief and different colleagues. IA is partially supported by grants from Takeda CW2680521; ANID/FONDECYT Regular (1210195 and 1210176); ANID/FONDAP/15150012; and ReDLat, supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Aging (R01 AG057234), Alzheimer’s Association (SG-20-725707), Rainwater Charitable foundation - and Global Brain Health Institute)]. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the author and do not represent the official views of these institutions.

References

- 1.Nunez R et al. (2019) What happened to cognitive science? Nat Hum Behav 3 (8), 782–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibáñez A and García AM (2018) Contextual Cognition: The Sensus Communis of a Situated Mind, Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luppi AI et al. (2022) A synergistic core for human brain evolution and cognition. Nat Neurosci 25 (6), 771–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genon S et al. (2018) How to Characterize the Function of a Brain Region. Trends Cogn Sci 22 (4), 350–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabinovich MI et al. (2015) Dynamical bridge between brain and mind. Trends Cogn Sci 19 (8), 453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Z and Firestone C (2020) The Dark Room Problem. Trends Cogn Sci 24 (5), 346–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krakauer JW et al. (2017) Neuroscience Needs Behavior: Correcting a Reductionist Bias. Neuron 93 (3), 480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibanez A and Manes F (2012) Contextual social cognition and the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 78 (17), 1354–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pessoa L et al. (2022) Refocusing neuroscience: moving away from mental categories and towards complex behaviours. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 377 (1844), 20200534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartwigsen G (2018) Flexible Redistribution in Cognitive Networks. Trends Cogn Sci 22 (8), 687–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonkusare S et al. (2019) Naturalistic Stimuli in Neuroscience: Critically Acclaimed. Trends Cogn Sci 23 (8), 699–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deco G et al. (2021) Revisiting the global workspace orchestrating the hierarchical organization of the human brain. Nat Hum Behav 5 (4), 497–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]